Introduction

Any company, regardless of size or field of activity, can face several strategic and tactical challenges, especially when there are sudden economic changes, caused by emergencies and unexpected events. In the current context, influenced by Covid-19, most entrepreneurs focus on protecting employees, a clearer understanding of the risks that may arise in the company’s business and crisis management; as a consequence, business plans, revenue and expenditure budgets and the cash flow of companies is constantly changing from day to day.

The occurrence of unpredictable events, such as Covid-19, can have an impact on expected results and profitability, but most importantly it can quickly generate cash flow tensions or even a financial liquidity crisis. Given the importance of cash flow at such times, entrepreneurs need to develop a management plan for available resources until the situation stabilizes. For this, it is essential to consider a perspective on the whole ecosystem that supports the business, as well as the implications of the decisions taken. Therefore, even in an uncertain horizon, good management is based on anticipation and planning.

Knowing that the business is essentially an integrated cash flow system driven by management decisions, the paper presents and analyzes a topic of great interest to businesses in crisis conditions and suggests the treasury budget as a cash flow planning tool, with relevance for business survival, growth and profitability.

The issue is approached in terms of the importance that the treasury budget has in making investment, operational and financing decisions in business, in order to maintain financial balance.

In this context, the first part of our paper describes the concepts that define the company’s treasury and presents the general framework for managing the company’s cash flows. In order to achieve this objective, the qualitative research methodology was used, as several scientific

papers from the literature were analyzed. The research is based on an extensive documentation; it is scientifically based on a comprehensive and relevant bibliographic material, highlighted in the bibliographic references. The references include specialized books, articles, studies, laws and standards, having as source both Romanian and foreign literature. The sources have a great variety, a multidisciplinary content and support our approach.

In the second part of the paper, we performed a quantitative research study, using as a research tool the case study. Through this quantitative approach we aimed to present a practical model for preparing the treasury budget, using data from a company in the field of wood processing.

The results of this research can be included in an integrated model for assisting managerial decisions. Through this model we aim to place the treasury budget in the sphere of management tools par excellence, as treasury forecasts allow both the anticipation of the company’s financial difficulties and the optimization of financing solutions.

Literature Review

The impact of the crisis generated by the Covid-19 pandemic was also felt strongly by the Romanian economy, which was affected by a substantial slowdown in growth, with negative and immediate effects on the population and enterprises, targeting mainly jobs and sales volume. Among the factors that determined the decline of companies, we can list: major difficulties in providing the necessary financing and liquidity, blocking credit, declining demand for products and services, high taxation, rising prices for raw materials, energy and food, exchange rate increases and inflation, the financial blockage generated by late payments, the unstable legislative framework, the low degree of absorption of community funds, insufficient measures to support enterprises during the crisis.

These problems affected all types of companies, that were suddenly faced with late payments from customers (who also had cash flow problems), increased costs for repaying loans committed in foreign currency due to the depreciation of the national currency, the decrease in revenue caused by a decrease in demand for products and services offered, etc.

Numerous research studies in the field show the importance of traditional budgeting, which was practically proven in periods of stability. According to Berland (2000), in a predictable environment, budgeting allows production optimization, prolongs internal predictability and simplifies resource allocation mechanisms. But in the context of a crisis, budgets have a reduced capacity to play the roles traditionally assigned: goal setting, resource allocation and motivation. This is mainly explained by the high degree of uncertainty, which forces budgets to deviate from their objectives.

In the conception of several authors, in a turbulent environment, the budget is used as a reflection tool to understand the environment (Gervais, 2009). This turbulent environment results from “the uncertainty of the actors’ behavior (unpredictability of their actions) and from the dynamic complexity of the environment in which they operate” (Gervais, 2009). Despite the turbulent context, organizations pay continuous attention to the dynamic relationship between objectives and resources, not only during the budget preparation period, but throughout the budget year. Instability requires flexibility, and in the context of the crisis, budgets play a new economic role: to meet the demands of investors (Bescos, 2011).

One of the characteristics of contemporary organizations is their concern to develop efficient management systems and practices, which requires the concentration of efforts in the direction of treasury management. According to Ross et al. (2016), organizations with different sizes face problems that require distinct approaches and appropriate tools, depending on the nature and complexity of the projects undertaken. Therefore, a fast and efficient approach to cash flow prediction is highly desirable. On the other hand, Scott (2007) states that, in terms of the financial decision-making process, a careful analysis of cash flow assesses the decisions made by managers regarding the allocation of financial resources based on the impact on the company’s ability to generate future cash flows.

Starting from the distinction between cash flow and cash, in the opinion of Sherman (2010), treasury management (cash flow) refers to the process of anticipation and planning of receipts and payments, while cash management refers to the processes of managing short-term liquidity of the enterprise in order to optimize its results. According to Ekanem (2010), managers need to consider several key elements for effective cash flow management. These elements include people and their mood (business executives, managers and employees), support network (business professionals), key performance indicators, along with appropriate management tools and techniques. For successful implementation, they must operate in an environment that encourages continuous learning and improvement, but always paying attention to the workload and working hours of their employees: bad time management and heavy workload can lead to burnout, that can affect employees’ health and performance (Lie & Mihaita, 2015). On the other hand, inaccurate cash flow prediction and inadequate cash management lead to financial problems and negative cash flows (Kaka, Price, 1993).

Anthony (1988) considers that effectiveness and efficiency are the criteria for evaluating the actions of managers, and the role of the budget in achieving them is important, as it allows the translation of medium and long-term strategic plans into short-term action programs, ensures budget control, coordinates the decision-making process and ensures the convergence of the strategic objectives of the enterprise.

Often, in small and medium enterprises there are no independent financial departments and because of this the manager is forced to manage both the practical aspects and the financial aspects of the sector he is leading. This situation involves making decisions whose consequences are difficult to quantify and which can shorten the life of the company in question. Consequently, it is necessary to have a clear separation of financial activity, regardless of the type of company, and if this is not possible, the manager must have a thorough knowledge of financial management (Nicolae, 2009).

Although it is recognized that uncertainty management is a necessary condition for effective project management, it can be assumed that it should become more sophisticated before practical results can be observed (Atkinson et al., 2006).

Methodology

Field research is the main part of the paper, this being directed towards current phenomena, analyzed in the real context of the company that is the object of the study. Regarding the method of data collection, for the case study we used data provided by the company under study. In order to complete the research, some data were collected by interview.

The building of the case study is explained by a step-by-step approach. The stages to be covered in the budget process are as follows: (1) gathering the necessary information; (2) preparation of partial treasury budgets; (3) elaboration and adjustment of the treasury budget.

Gathering information is the first step in the budgeting process and is the basis for the next steps. Here the resources available to the company are identified – they are reflected in the balance sheet; the costs related to certain activities carried out are also identified in this stage. Due to the impact of each activity on the cash flow of the enterprise, it is important to identify all the factors that may have an influence on it.

The following steps are developed for the preparation of the partial treasury budgets, the elaboration and adjustment of the final treasury budget. It is necessary from the beginning, as an important step, to establish the prediction horizon of the treasury budget, because in the case of short-term prediction, many parameters are known deterministically. Therefore, the budgets must describe the general lines of the financial evolution, to ensure a margin of maneuver within their own provisions and the possibility to be revised.

Crisis management measures, based on the treasury budget, strengthen our belief that non-specific cash flow forecasting instruments are valid in a highly regulated world, without major dangers or in the absence of essential trade-offs to overcome certain events. But in a more uncertain context, marked by the acceleration of competition or the emergence of a crisis such as Covid-19, it becomes essential for the company to adopt a dedicated cash forecasting tool, according to its business model. Without cash flow forecasts, the company risks running out of cash unexpectedly and therefore going into insolvency or even bankruptcy. We use our experience and also other research in this area to suggest some measures to guide a company to this end.

Use of the treasury budget for forecasting cash flows. Case study

The Treasury registers the cash flows of the various decisions taken by the enterprise; these decisions, depending on the settlement term considered, can be long-term decisions (concerning investments and their financing) and short-term decisions (related to the operation of the enterprise and of its operation). Each of these decisions, regardless of the branch in which it takes place, ultimately materializes in a flow of income and expenditure, which generates receipts and payments, which will be administered in the short term to maintain the balance of the treasury.

Through the budget, it will be possible to highlight the treasury surpluses or deficits from time to time and, implicitly, it will be possible to take decisions regarding the treasury management that aim at:

- ensuring the availability of financing (capital increase, long, medium- and short-term loans) at their lowest cost;

- increasing the efficiency of collecting the company’s receivables without affecting the policy towards customers; balanced staggering of the maturity of the company’s payment obligations;

- ensuring the treasury at zero level, in order to avoid financing or opportunity costs;

- investing the treasury surplus as profitable and as little risky as possible, etc.

In addition to the theoretical considerations presented above, we will further present, in a case study, a practical model for preparing the treasury budget for a company in the field of wood processing. Due to privacy reasons, the company’s name used in the study will be anonymized and referred to as Company X.

Gathering information

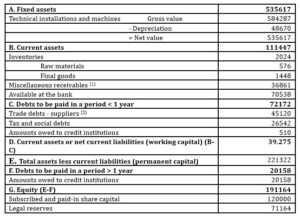

The treasury budget gathers the budgetary information of different financial years, hence the obligation to collect the necessary information. The information necessary for the elaboration of the treasury budget for the current year is collected from the balance sheet of the previous year and from the other approved budgets of the current year. Therefore, for the preparation of the budget, three records and forecast documents are used: the opening balance sheet (balance sheet for the year ended – Table 1), the forecast income statement and the forecast balance sheet.

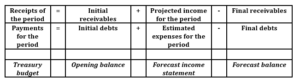

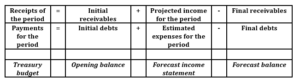

The treasury is based on the financial flows of a certain management period, determined by the income and expenses of the period (income statement) and by the change in receivables and payables at the beginning and end of the period (opening balance sheet and forecast balance sheet), according to relations:

Table 1: Annual financial situation Balance sheet at 31.12. 2019 (simplified)

- The receivables of the clients are estimated to be collected: 60% in February and 40% in March 2020;

- The projected payments to the suppliers are made as follows: 55% of the debt value in the first month and 45% in the second month; of which: VAT payable 2,563 u.m.

Other information necessary for the elaboration of the treasury budget of year 2020: VAT to be paid until the 25th of the following month; VAT rate: 19%; Salaries are paid in the current month; Payment dividends are paid in June; Taxes and fees related to gross salaries due by the company to the state budget are considered 80% of the level of gross salaries; Debts to the budget regarding salaries are paid in the month following the payment of salaries; Income tax rate: 16%; Advance payment of income tax per quarter I and quarter II: in March – 4,000 u.m. and in June – 5,000 u.m.; The profit tax for the previous year is paid in April; The share of VAT generating expenses in the total expenses of the enterprise: fixed expenses 50%, variable expenses 60%, mixed expenses 40%, sales expenses 70%.

Preparation of partial treasury budgets

Cash flow is one of the key factors influencing the survival of small businesses, and the difference between the time of invoicing and the time of collection or payment influences the solvency of the

business. Even if it has a profit margin, if a company does not practice good cash flow management, it operates at a significant risk. This becomes even more important for SME owners when operating in a climate of continued global economic volatility.

That is why, while elaborating the treasury budget, the distinction between cash accounting and accrual accounting must be considered, because there are situations in which an enterprise can end the financial year with profit, but at the same time it can register a negative treasury, due precisely to the gap between the moment of registering in the accounting of the expenses and incomes and the moment of their maturity as receipts and payments. The treasury budget thus becomes a management tool that translates in monetary terms (receipts and payments) the expenses and revenues generated by the scheduled activities of the company, aiming to permanently ensure the payment capacity of the company, by synchronizing receipts with payments.

The treasury budget can be prepared for different periods of time, depending on the objectives of the company and the maturities of receipts and payments. Thus, the decision can be made to prepare annual budgets, when the maturities of receipts and payments are quarterly or greater than 90 days, budgets for several months (4-6 months), when the maturities of receipts and payments are monthly and greater than 30 days and day-to-month budgets. However, a realistic budgeting of the treasury is made for a management period of one year, with breakdown by month and breakdown by week for the first three months of the year.

In order to build the company’s treasury budget, three distinct partial budgets are drawn up a priori: a revenue budget, a payments budget, a VAT budget. The amounts related to expenditures and revenues registered in the budgets are without VAT. Receipts and payments must be expressed with VAT included, with the obligation to determine at the end of each month the amount representing “VAT payable” or “VAT recoverable”, which will be settled with the state budget.

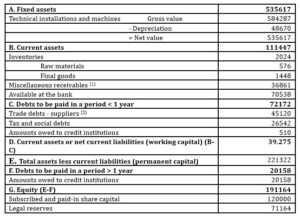

Revenue Budget

Receipts (cash inflows) refer to: settlements with customers (reflected in the sales budget), down payments received from customers, production of fixed assets (reflected in the investment budget), to which we add the financial receipts from: capital increases; obtaining a loan or selling a new issue of securities; rents, interest, dividends and other income collected.

The forecast of receipts is, in most cases, passed from the sales budget to the receipts from sales. Once the annual turnover and its monthly distribution are established, the forecast of receipts is based on a statistical record of the time staggering of the collection of monthly revenues. Furthermore, the forecast must consider the changes that may occur in the structure of sales and the degree of solvency of the company’s customers, which will influence the gap between delivery and collection data, which is often 30-90 days.

The budget has two areas:

- The upper area of the table allows the calculation of the turnover (including VAT) and the VAT collected for the current month (which is taken over in the VAT Budget)

- The lower area of the table highlights the receivables from customers and other receivables which appear in the balance sheet of the previous year, taking into account the discrepancies on receipts, due to the agreed settlement terms.

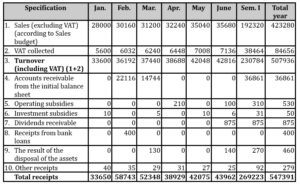

The Revenue budget of Company X, for year 2020, is presented as follows (Table 2):

Table 2: Revenue Budget

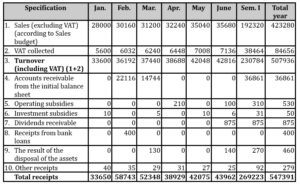

Payment Budget

Payments (cash outflows) refer to the payment of debts caused by purchases (reflected in the supply budget), payment of salaries and premiums, operating, administration and distribution expenses (included in the production expenditure budget, in the distribution expenditure budget, in the budget of administrative expenses, etc.), acquisitions of fixed assets (reflected in the investment budget), taxes and fees due to the state budget, to which payments of a financial nature are added: interest and dividends paid, loan repayments, purchases of financial securities, redemption of securities issued by the company.

Payments (cash outflows) refer to the payment of debts caused by purchases (reflected in the supply budget), payment of salaries and premiums, operating, administration and distribution expenses (included in the production expenditure budget, in the distribution expenditure budget, in the budget of administrative expenses, etc.), acquisitions of fixed assets (reflected in the investment budget), taxes and fees due to the state budget, to which payments of a financial nature are added: interest and dividends paid, loan repayments, purchases of financial securities, redemption of securities issued by the company.

The forecast of payments is made on the basis of projected expenditure and the planned staggering of payments and differs according to the nature of the expenditure, such as expenditure on material supplies, which is planned according to the manufacturing schedule or staff costs, which are provided considering the company’s labor policy, etc.

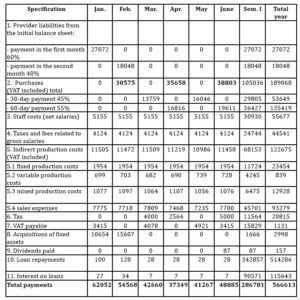

The payments budget (Table 3) groups the expenditures appearing in the expenditure budgets according to their way of regulation. The amount representing the “VAT payable” for the month, established in the VAT Budget, is also entered here.

Table 3: Budget of payments

VAT Budget

This budget allows the calculation of “VAT payable” according to the rule:

|

VAT payable for month M

|

=

|

VAT collected for month M

|

–

|

Deductible VAT for month M

|

The VAT payable for a given month is paid during the following month.

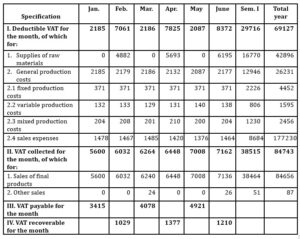

The construction of the treasury budget requires the determination of the corresponding amount “deductible VAT” for the month and, therefore, the restoration of purchases of any kind.

The top of the table allows you to highlight purchases with VAT included, so that you

can determine the amount representing “deductible VAT” for the month.

The bottom of the table enables the establishment of the “VAT payable” for the month, using the rule stated above; it represents the main area of the VAT budget.

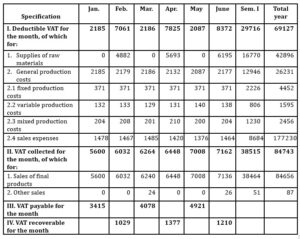

Based on the information collected, the VAT Budget of Company X is presented as follows (Table 4):

Table 4: VAT budget

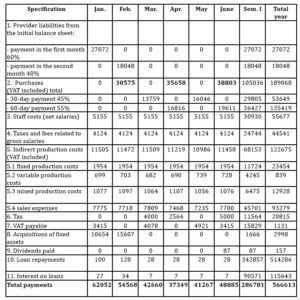

Preparation of the treasury budget itself

Once the partial treasury budgets have been established, the treasury budget is drawn up.

The treasury budget is generally presented in two successive versions and the budget work consists of:

- a) establishing an initial version of the budget, which contains the gross monthly cash balances;

- b) the development of an adjusted treasury budget, which considers the financial policy of the company.

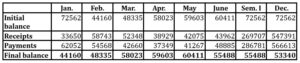

- a) Initial version of the budget. In this perspective, month by month, the revenues are compared with the payments, so that they are taken over in the previous partial budgets; at the same time, the availabilities that appear in the balance sheet of the previous year are considered.

This version is set column by column because the final cash balance of a given month becomes the initial balance of the following month.

- b) The adjusted (actual) treasury budget resumes the total receipts, the total payments and, considering the initial treasury, will release the final treasury balance every month. These final cash balances may be deficits or surpluses. Only the financial manager can balance this treasury, so that the adjusted treasury budget must present zero or positive cash balances, as it will consider the financing policy adopted by the enterprise to balance its treasury. Preventive negotiation of short-term financing is generally less costly and safer than resorting to possible short-term loans in the event of a negative treasury.

The following rules are considered for the construction of the treasury budget:

- the initial balance in January corresponds to the treasury in the initial balance sheet;

- the final cash balance of one month is the initial balance of the following month;

- the final balance of December, after applying financing solutions, corresponds to the treasury from the forecast balance.

Final balance = Initial balance + Receipts – Payments

When the final balance is positive, the company has a cash surplus, which in the short term should be deposited in the bank to avoid the opportunity cost.

If this balance is negative, the company has a cash deficit, which must be absorbed by short-term financing, usually in the form of short-term bank loans, etc.

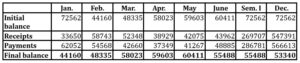

After adjusting the balances, the treasury budget (adjusted) or the cash flow plan (table 5) is drawn up.

Table 5: Treasury budget

The treasury budget is not flexible but needs to be reviewed frequently. Resulting from all the other budgets that make up the company’s budget network, it bears all the effects of their changes: slowing or accelerating sales, rising wages, changes in commodity prices, changes in fiscal policy, etc. All these reasons show the need for frequent adjustments in order to have a budget as realistic as possible.

The company will need to test financial plans under stress in several scenarios, to understand the potential impact on financial performance and to assess its duration. When the business is significantly affected and previous budget assumptions and business plans are no longer relevant, the company must consider minimum operational requirements, including essential dependencies on manpower, suppliers, location and technology. Thus, a detailed analysis of the nature of receipts and payments is required, and the cash flow forecasting instrument should therefore be constructed according to the typology of receipts and payments, and not according to budgetary elements.

During the process of elaborating the treasury budgets, in a crisis situation, such as the crisis generated by COVID-19, the company must pay attention to the communication it has with different actors on the market:

- in relationship with customers, during the Covid-19 crisis, the company risks facing the absence of new orders or the collection of advance payments, with possible difficulty in fulfilling orders due to interruption of production process or suppliers, difficulties in recovering the value of goods and services in case of customers’ inability to pay. In this situation, it is important to have direct communication between business partners in order to extend the deadlines or to invoke “force majeure” or “fortuitous event”. These proactive actions will help mitigate damages or liability for non-performance of obligations towards customers.

- in its relationship with suppliers, the company must maintain regular contact with regard to their ability to deliver goods and provide services, as well as with regard to their plans to recover their value, thus enabling them to consider alternative options for receiving supply in a timely manner.

- in relation to creditors and investors, the company must analyze the terms and conditions of loan agreements, to identify debts and avoid breaches of contracts. These analyses will also have the benefit of giving the company the opportunity to proactively manage dialogue and communication with creditors on any necessary changes to existing conditions or refinancing agreements.

- in relation to government and regulatory authorities, the company should consult with their legal teams for advice on possible obligations, as well as with the business units, to see how to manage the communication of ongoing infringements and the collection of evidence, if any.

Pilotage measures in crisis situations based on the treasury budget

The companies’ performances are the result of mobilizing all the resources they have, and in crisis situations the managers explore all the methods of flexibility and adaptation to the internal and external requirements of the organization. Having permanently as reference the treasury budget, the enterprises can resort to a series of measures that would allow them to pilot the enterprise in these unfavorable conditions:

- Monitoring and updating the treasury budget as often as possible. In times of crisis, the treasury budget becomes an extremely important tool, which provides a clear picture of receipts and payments. A correct planning and a permanent monitoring of them allows detailed analyses regarding the past financial results, the cash flow registered in a certain time interval, the activity of the cost and profit centers and taking the required corrective measures in order to remedy some unfavorable situations, which negatively affect the profitability of the business.

- Avoiding liquidity blockages. During this period when many companies are likely to have fluctuations in sales or will face problems caused by very large increases in expenses, late collection of invoices from customers or discontinuity in the supply of stocks (because the supplier is blocked due to an outbreak of infection, because the supplier requires prepayment or reduces the payment term), due to stockouts (because in some periods sales are very slow and in others orders are very high). All these negative shocks can be anticipated by simulating the impact on cash flow and working on the basis of several stress scenarios to avoid liquidity blockages, which inevitably increase the risk of going into insolvency.

- Ensuring a cash reserve for crisis situations can be achieved mainly by opening a short-term credit line, in order to cover the immediate need for cash caused by the gap between receipts and payments, the purchase of stocks, the payment of invoices or the payment of unexpected expenses. If necessary, the sale of assets that are not essential for the core business may also be used. Another possibility is to resort to factoring (financing of receivables), a method that does not require material guarantees and does not affect the degree of indebtedness or other financial indicators.

- Choosing quality partners. The company must always consider the quality of the partners it collaborates with, whether they are a customer, a supplier, a bank or a strategic business partner. It is very important to know which partner can be trusted when it is necessary to request the postponement of payment terms or credit restructuring or renegotiation of contracts with customers and suppliers, to reduce the average duration of receivables collection and to extend suppliers’ payment terms.

- Adapting the business to the emergency situation (resilience strategy). Given the rapidly changing context in which it operates, the company must be flexible, ready to take new measures in terms of business strategy, such as changing the product, accelerating sales and revenue, accelerating the liquidation of stocks, materialization of gains from the liquidation of stocks, changes of the client portfolio, ensuring the cash available for situations of crisis, etc.

- Detailed analysis of expenses. In order to maintain the activity going, it is important to reduce variable costs as much as possible and to keep fixed costs under control. The company must analyze operating costs and must consider reducing or discarding all non-essential expenses. Rational management of expenses, adapted to the level of monthly receipts, can be a very good resource (action) for maintaining a constant positive cash flow.

- Reviewing investment plans. The company must assess the possibilities for short-term capital raising, debt refinancing or additional support from banks or investors, as well as political support from the government. At the same time, considering the cash flow forecasts, you have to answer a series of questions such as: Which investments can be postponed until the situation improves? Which of them should be reconsidered? What investments are needed to return to positions and create a competitive advantage?

- Staff motivation. Another aspect that must be controlled in moments of uncertainty is the level of motivation of the team. Permanent communication regarding the existing situation, involvement in projects that ensure the survival of the company, showing appreciation for the work done, offering empathic help for personal issues, are elements that strengthen staff motivation. Encouraging work from home and mutual support are the best ways to deal with this time of crisis.

Conclusions

To conclude, we can say with conviction that the treasury budget is a very useful tool for the company’s financial strategy and management decision-making, because detailed knowledge of cash flows helps the long-term development of the company. The policies of an enterprise can only be conceived from the cash flow, which is the key element of any business plan, and the movement of flows is the “great art” in the decision-making process.

Companies around the world are trying to accept the effects that current events have had on cash flows and their business. Although the risks are considerable, the crisis also reveals areas where companies can develop resilience and where they can reshape in the post-crisis period.

Acting in an uncertain horizon, with an unstable cash flow, it is essential for companies to follow the cash flow forecasts throughout the year, at least at monthly intervals and in case of atypical events. Good control of the projected cash flow, either in the “isolation” phase or a fortiori during takeover, can be a decisive competitive advantage for organizations’ management and their ability to recover. Thus, financial managers can determine approximately the periods during which the treasury will have a surplus or a deficit, provisions that are found in the treasury budget.

Efficient management of the cash flow generated by the activities carried out can help the company in controlling and managing resources, reducing costs, maintaining financial stability, anticipating problems and maximizing the results obtained, while incorrect management of the treasury is often the main cause of bankruptcies.

In order to maintain the financial balance, it becomes necessary to use the treasury budget, which predicts the ratios between receipts and payments and identifies possible credit needs. Therefore, we can say that the treasury budget is a forecast dashboard of the company’s liquidity supply and demand, which allows financial managers to optimize the company’s financial results.

The cash flow statement has been integrated for more than fifteen years in the financial reporting system of Romanian enterprises, but it is not regularly considered by managers in the decision-making process. This statement is consistent with the findings of other researchers, including Mautz and Angell (2009), regarding the confusion and difficulties of understanding that the cash flow situation still raises for users of financial statements. We hope that our approach has succeeded in presenting, theoretically and applicatively, the importance of using the treasury budget in managing cash flows and that it will determine more and more managers to add it to the other performance management tools used in the management process.

The issues addressed in this paper create the premises for expanding research through an approach that allows budgetary control of the treasury and optimizing the company’s cash flow, as well as identifying other methods and tools for managing the company’s treasury. Having an adequate system of budgetary control would allow companies to improve their managerial attitude and performance and provide useful information for solving financial challenges.

Acknowledgment

This article is financed by the University POLITEHNICA of Bucharest, through the project “Engineer in Europe” in online system, registered at MEC under no. 457 / GP / 06.08.2020, by using the fund for financing special situations that cannot be integrated in the form of financing public higher education institutions.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Anthony, R. N. (1988), The Management Control Function, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

- Atkinson, R., Crawford, L., and Ward, S., (2006). ‘Fundamental uncertainties inprojects and the scope of project management’,International Journal of Project Management, 24 (8), 687–698.

- Berland, N. (2000), ‘Fonctions du controle budgetaire et turbulence’, 21-eme Congres de l’Association Francais de Comptabilite, Angers, France.

- Bescos, P.L. (2011), ‘L’utilisation du budget dans un contexte de crise: le role de la relation entre objectifs et ressources’,32eme Congrès de l’Association Francais de Comptabilite à Montpellier, France.

- Ekanem, I.(2010). ‘Liquidity Management in Small Firms: A Learning Perspective’, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 17, no 1, 123 -138.

- Gervais, M. (2009). ‘Contrôle de gestion. 8ème édition’, Paris: Economica Gestion.

- Kaka, A.P. and Price, A.D.F., ‘Modelling standard cost commitment curves for contractors cash flow forecasting’, Construction Management and Economics, 11(4), (1993), 271–283.

- Lie, I.R. and Mihăiță, N.V (2015). ‘Job Satisfaction and Causes of Burnout in Romania’, Proceedings of the 25th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9860419-4-5,7-8 May 2015, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 231-239.

- Mautz, R. and Angell R.J., (2009) ‘Reading the statement of cash flows’, Commercial Lending Review, Mai-Juin, 15-20.

- Nicolae, S. (2009) ‘The Financial Analysis Procedure for Small Enterprises in Romania’, Proceedings of the 13th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9821489-2-1, 9-10 November 2009, Marrakech, Morocco, 466-480.

- Ross, S.A., Westerfield, R.W., Jaffe, J. And Jordan, B.D. (2016), ‘Corporate Finance’, ed. XI-a, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Scott, S. (2007). ‘The importance of cash-flow analysis for small businesses’, Commercial Lending Review, Mars-April, 37-48.

- Sherman, D. (2010). ‘Outils de gestion de trésorerie pour les petites et moyennes entreprises’, Institut Canadien des Comptables Agréés, Toronto.

- Sponem, S. and Lambert, C. (2010). ‘Pratiques budgétaires, rôles et critiques du budget. Perception des DAF et des contrôleurs de gestion’, Comptabilité – Contrôle – Audit 16.