04 September 2021: Articles

Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum and Pneumothorax in Nonintubated COVID-19 Patients: A Multicenter Case Series

Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Angela Iuorio1A, Francesca Nagar2E*, Laura Attianese2B, Anna GrassoDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.933405

Am J Case Rep 2021; 22:e933405

Abstract

BACKGROUND: COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 has become a global pandemic. Diagnosis is based on clinical features, nasopharyngeal swab analyzed with real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, and computer tomography (CT) scan pathognomonic signs. The most common symptoms associated with COVID-19 include fever, coughing, and dyspnea. The main complications are acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, kidney failure, bacterial superinfections, coagulation abnormalities with thromboembolic events, sepsis, and even death. The common CT manifestations of COVID-19 are ground-glass opacities with reticular opacities and consolidations. Bilateral lung involvement can be present, especially in the posterior parts and peripheral areas. Pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and lymphadenopathy are rarely described. Spontaneous pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum have been observed as complications in patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia during mechanical ventilation or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, as well as in patients with spontaneous breathing receiving only oxygen therapy via nasal cannula or masks.

CASE REPORT: We present 2 cases of pneumomediastinum with and without pneumothorax in patients with active SARS-Cov-2 infection and 1 case of spontaneous pneumothorax in a patient with a history of paucisymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. In these 3 male patients, ages 78, 73, and 70 years, respectively, COVID-19 was diagnosed through nasopharyngeal sampling tests and the presence of acute respiratory distress syndrome.

CONCLUSIONS: Both pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum, although rare, may be complications during or after SARS-CoV-2 infection even in patients who are spontaneously breathing. The aim of this study was to describe an increasingly frequent event whose early recognition can modify the prognosis of patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pneumomediastinum, Diagnostic, Pneumothorax, COVID-19, Humans, Mediastinal Emphysema, Pandemics

Background

Pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum, rarely both, can be present in the context of COVID-19, not only in patients receiving mechanical ventilation or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, but also in patients with spontaneous breathing receiving only oxygen therapy via nasal cannula or masks [1].

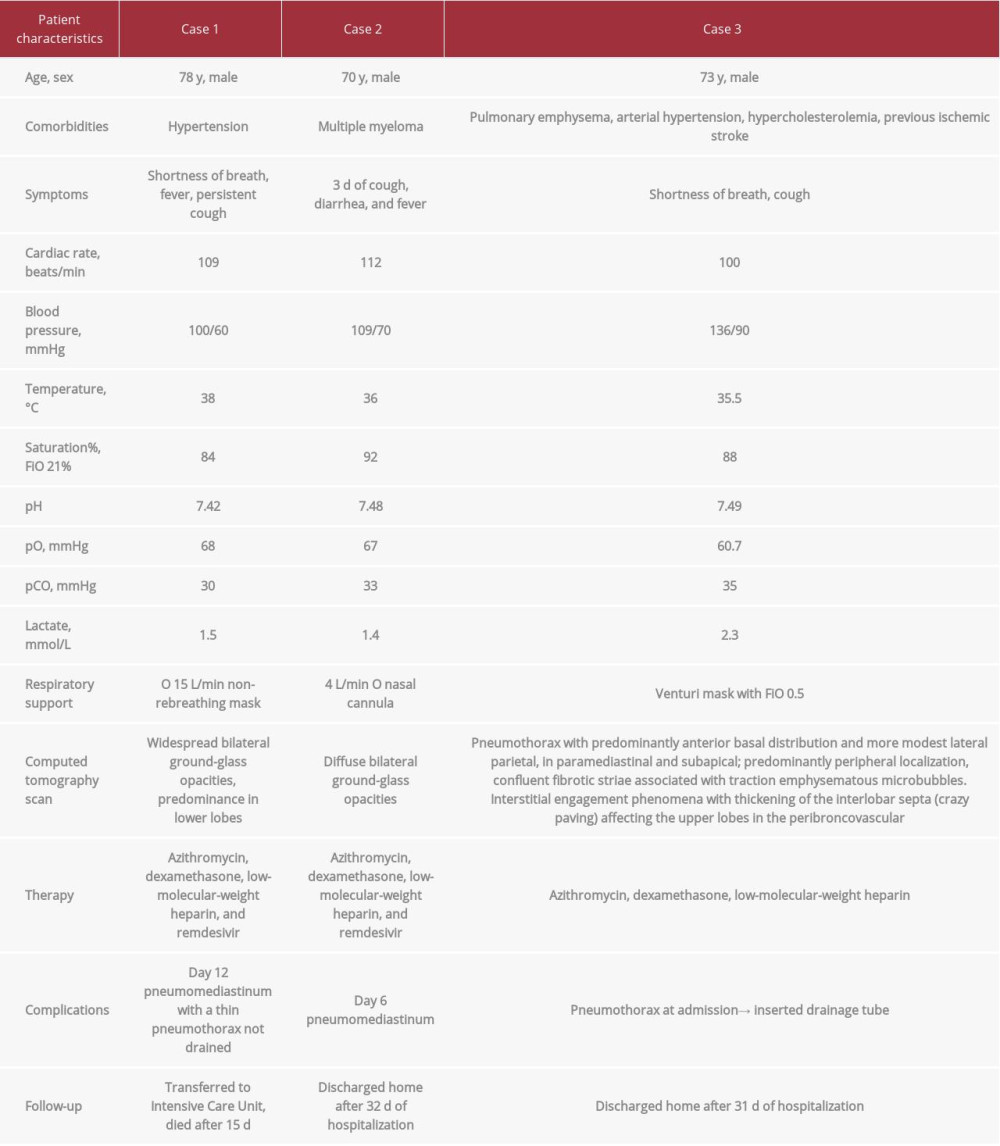

Here we present 2 cases of pneumomediastinum with and without pneumothorax in patients with active SARS-CoV-2 infection and 1 case of spontaneous pneumothorax in a patient with a history of paucisymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 1).

Case Reports

CASE 1:

A 78-year-old man with a past medical history of atrial fibrillation and diabetes mellitus was admitted to the Emergency Department reporting the following symptoms: shortness of breath, fever, and persistent cough. On physical examination, he was febrile, tachypneic with an initial SpO2 of 86%, with FiO2 21% and 92% on non-rebreather mask with O2 of 15 L/min. Blood gas analysis, complete blood count, and biochemical analysis were obtained (see Table 1). COVID-19 was suspected, and real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was performed from a nasopharyngeal swab.

Severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) secondary to SARS-CoV-2 viral pneumonia was diagnosed, with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 110. A computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained and revealed widespread bilateral ground-glass opacities, with a predominance in the lower lobes of the lungs. Treatment consisted in azithromycin, dexamethasone, low-molecular-weight heparin, and remdesivir. A non-rebreathing mask (O2, 15 L/min was required to maintain his oxygenation.

On day 12 of the patient’s hospitalization, he developed violent coughing followed by chest pain and worsening hypoxemia. CT scan was repeated and showed an increase in bilateral areas of interstitium-alveolar thickening, with bilateral ground-grass, crazy-paving appearance and pleural thickening in the posterior region. According to the scoring method published by Chung et al [2], the total lung severity score was 20 out of 20.

The presence of pneumomediastinum located mainly in the left anterior paracardiac area and along the left hilum (maximum thickness, 12 mm) was detected, together with a thin pneumothorax flap on the left in an antero-medial arrangement, with a maximum thickness of 6 mm (Figure 1). Subsequently, a transfer to the Intensive Care Unit for monitored care was then requested. Given its small size, pneumothorax was not drained. The patient died after 15 days in the Intensive Care Unit of infectious complications related to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia, which was not present before pneumomediastinum developed.

CASE 2:

A 70-year-old man with a past medical history of multiple myeloma was admitted to the Emergency Department reporting 3 days of cough, diarrhea, and fever. On physical examination, he was afebrile and tachypneic with initial SpO2 of 92% without oxygen and 99% on 4 L/min O2 via nasal cannula.

Blood gas analysis, complete blood count, and biochemical analysis were obtained and showed respiratory alkalosis, decreased lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte count, and increased C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, neutrophil count, neutrophil ratio, and lactate dehydrogenase. Chest X-ray revealed bilateral diffuse infiltrations. COVID-19 was suspected, and real-time PCR testing was performed from a nasopharyngeal swab. ARDS secondary to SARS-CoV-2 viral pneumonia was diagnosed, with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 190. Therefore, treatment with azithromycin, dexamethasone, low-molecular-weight heparin, and remdesivir was provided.

On day 6 of the patient’s hospitalization, his hypoxia worsened, requiring 15 L/min O2 non-rebreathing mask. A thoracic CT scan showed bilateral areas of interstitium-alveolar thickening with a ground-glass and crazy-paving appearance and pleural thickening in the posterior region, as well as small (maximum 12×4 mm and 15×2 mm) mediastinal air collections on the left and in correspondence with the left hilum (Figure 2).

During his hospitalization, the patient was managed conservatively and a slowly decreasing O2 requirement was noted. After 32 days from hospital admission, the patient was discharged home on 2 L/min O2 via nasal cannula.

CASE 3:

A 73-year-old man with a past medical history of pulmonary emphysema, arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, previous ischemic stroke, and paucisymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection 1 month earlier was admitted to the Emergency Department for shortness of breath and cough. The patient had been recovering, following 2 real-time PCR tests from nasopharyngeal swab that were negative. On physical examination, he was afebrile and tachypneic, and the initial SpO2 was 88% without oxygen and 93% on Venturi mask with FiO2 0.5. Blood gas analysis revealed respiratory alkalosis with hypoxia and increased lac-tate. Thoracic CT showed pneumothorax with a predominantly anterior basal distribution and more modest lateral parietal, in paramediastinal and subapical, predominantly peripheral localization, confluent fibrotic striae associated with traction emphysematous microbubbles (Figure 3). Interstitial engagement phenomena with thickening of the interlobar septa (crazy paving) was affecting the upper lobes in the peribroncovascular. A chest drain was inserted with a normalization of vital parameters and blood gas analysis. Chest tube drain was placed in suction at −20 cm H2O; a persistent air leak was present and a chemical pleurodesis was performed with a successful result and stop of air leak. Chest radiography confirmed lung re- expansion, and on day 30 the tube was removed. During hospitalization, the patient’s general condition remained stable.

Discussion

The entry of the SARS-CoV-2 into the alveolar cells of the host through binding between the spike protein and the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor, followed by replication of the virus, activates the host’s antiviral immune response with the production of proinflammatory cytokines and specific antibodies. Dysregulation of the host’s immune response can cause severe pneumonia characterized by massive alveolar damage resulting in severe ARDS, with greater involvement of pulmonary capillaries with thrombotic and vasculopathic phenomena [3].

After an incubation period from 2 to 14 days, principal symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia are fever, dry cough, and dyspnea; hypoxemia may occur as the disease progresses. Patients often have pulmonary parenchymal opacities on chest radiography. The main finding from CT examination is the presence of ground-glass opacities, usually bilateral, affecting more than 2 lobes, with a prominent peripheral localization [1,2].

Pneumothorax is a medical emergency that requires prompt treatment with the placement of a drain, and its presence should always be suspected in patients with a sudden deterioration of respiratory and cardiovascular function. Spontaneous pneumothorax with or without pneumomediastinum has been observed in patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, even in those with spontaneous breathing who are only receiving oxygen therapy [1,4]. The exact mechanism is not clear, but alveolar damage caused by SARS-CoV-2 promotes severe destruction of alveolar tissue resulting in bullae formation [5]. This damage has been demonstrated radiologically in studies showing the radiological progression from areas of consolidation to bullae [4].

Pneumomediastinum is the presence of air in the mediastinum and can be classified as spontaneous or secondary pneumomediastinum, caused by a penetrating trauma, rupture of a hollow viscus, or intrathoracic infections [6]. Diffuse alveolar injury in severe COVID-19 pneumonia and the pronounced cough developed may cause alveolar rupture [7] that may lead to air dissection along the broncho-vascular sheaths that spreads into the mediastinum [8]. This phenomenon is known as the Macklin effect. While spontaneous pneumomediastinum is considered a self-limiting condition, the progress of these patients should be monitored for the possibility of pneumomediastinum-related cardiovascular and respiratory complications [9]. According to a review by Elhakim et al [1], most cases of spontaneous pneumomediastinum in patients with COVID-19 identified in literature show spontaneous resolution with conservative management and have a favorable clinical course; however, a percentage of patients die, resulting in a mortality rate of 26%.

In our facilities, we have submitted patients to CT scans to diagnose pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum. CT examination is the main screening and diagnostic base for COVID-19 and for pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax, but due to infection control issues, portable chest radiography or lung ultrasound may be useful tools to evaluate lung lesions at bedside, including pneumothorax [10,11].

Conclusions

In conclusion, both pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum, although rare, may be complications during or after SARS-CoV-2 infection. They should be suspected in the event of worsening of respiratory and/or cardiovascular symptoms, even in patients who are spontaneously breathing, due to pathogenic pulmonary lesions from alveolar damage. Long-term follow-up of COVID-19 patients may be necessary to provide knowledge about the course of pulmonary sequelae and risk of pneumothorax [5].

Figures

References:

1.. Elhakim TS, Abdul HS, Pelaez Romero C, Rodriguez-Fuentes Y, Spontaneous pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema in COVID-19 pneumonia: a rare case and literature review: BMJ Case Rep, 2020; 13(12); e239489

2.. Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): Radiology, 2020; 295(1); 202-7

3.. Attaway AH, Scheraga RG, Bhimraj A, Severe covid-19 pneumonia: Pathogenesis and clinical management: BMJ, 2021; 372; n436

4.. Martinelli AW, Ingle T, Newman J, COVID-19 and pneumothorax: A multicentre retrospective case series: Eur Respir J, 2020; 56(5); 2002697

5.. Janssen ML, van Manen MJG, Cretier SE, Braunstahl GJ, Pneumothorax in patients with prior or current COVID-19 pneumonia: Respir Med Case Rep, 2020; 31; 101187

6.. Caceres M, Ali SZ, Braud R, Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: A comparative study and review of the literature: Ann Thorac Surg, 2008; 86(3); 962-66

7.. Sun R, Liu H, Wang X, Mediastinal emphysema, giant bulla, and pneumothorax developed during the course of COVID-19 pneumonia: Korean J Radiol, 2020; 21(5); 541-44

8.. Park SJ, Park JY, Jung J, Park SY, Clinical manifestations of spontaneous pneumomediastinum: Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2016; 49(4); 287-91

9.. Mohan V, Tauseen RA, Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in COVID-19: BMJ Case Rep, 2020; 13; e236519

10.. Jacobi A, Chung M, Bernheim A, Eber C, Portable chest X-ray in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): A pictorial review: Clin Imaging, 2020; 64; 35-42

11.. Li S, Qu YL, Tu MQ, Application of lung ultrasonography in critically ill patients with COVID-19: Echocardiography, 2020; 37(11); 1838-43

Figures

In Press

04 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.941835

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943042

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942578

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943801

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250