Communicating About COVID-19 in Four European Countries: Similarities and Differences in National Discourses in Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden

- 1Gothenburg Research Institute, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

- 2Department of Architecture and Construction Engineering, University of Girona, Girona, Spain

- 3Department of Agriculture, Mediterranea University of Reggio Calabria, Reggio Calabria, Italy

- 4Independent Researcher, Stockholm, Sweden

The pandemic spread of COVID-19 grew inexorably to be the main topic of global news after it was first identified in 2019 in China. This article analyzes how heads of state and heads of government in Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden framed the problems and solutions to the spread of the virus during the pandemic's initial phase. A Foucauldian-inspired method of problematization guides the narrative analysis, complemented by governmentality, risk communication, and taskscape theories. The results of the analysis show how the individual is conceptualized as a central actor and whose practices are framed as crucial to overcoming the crisis. Through invoking a sense of responsibility, sacrifice, and current life during the pandemic as a difficult time, the speeches allude to how people through changed behavior can/sould, contribute to the greater good. The individual is positioned as a key cause of, and solution to the problem; however, construing the individual as an indispensable actor to overcoming the crisis also means that the individual is laid open for reprehension. To facilitate the spread of the containment message and to support individual understanding of overt risk, the four countries' leadership also augment their conceptualization of the crisis with ideas of national identity to inspire the individual to contribute to the “battle” and “defeat” of the virus. The leadership does also embrace the important role of the national government in controlling the outbreak and the role of science, and trust in science, are also emphasized. The speeches analyzed in this paper can be understood as governance technologies; the spatial disciplining and self-governance demanded by the regimes create subject positions for individuals or groups. A debate on the rights and responsibilities of the citizen is another aspect that comes to the fore, considering how the containment strategies in all four countries proclaim the individual as a core agent in circumscribing the virus, and hence the individual's activities as potentially damaging to the fight against the pandemic. This throws into question the connection between individual autonomy as a democratic right and disciplinary mechanisms, sometimes phrased encouragingly and at other times in an enforcing way.

Introduction

The pandemic spread of the infectious disease COVID-19, caused by the respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has grown inexorably to be the main topic of global news after it was first identified in late 2019 in Wuhan, China. In an attempt to mitigate the consequences of SARS-CoV-2, governments have enhanced whole-of-society mechanisms by implementing a wide range of restrictions and limitations to prevent further spread of the virus. While many of these restrictions must be understood as having a positive effect on limiting the spread of the virus, these restrictions have also limited and transfigured the movement of people within and between countries. Furthermore, the effects of self-isolation, quarantine, social distancing and associated feelings of frustration, loneliness, worries about the future, and post-traumatic stress disorders have already been pronounced as significant psychosocial consequences of the pandemic (Giallonardo et al., 2020). Consequently, the virus itself and the measures to contain the virus have had enormous cumulative effects on societies globally.

In what follows, we analyze how heads of state and heads of government in four European countries have framed the problems and solutions in their communication on the implementation of strategies for contagion containment to halt or stop further spread of the disease. We approach this analysis from the understanding that the content of such communication is crucial to society, particularly when there is an acute need to create awareness and readiness for action amongst the receivers of the information (Argenti, 2002). In addition to providing information to the public, the communication of the people in office—be they constitutionally elected, merely symbolic, or with restricted governing power—can also be understood as a way to legitimize interventions and stabilize the system for sound decision-making (Renn and Levine, 1991; Shipunova et al., 2014).

In analyzing this body of communication, we find the concept of “governmentality” (Foucault, 2010) useful since the containment measures serve to governmentalize the pandemic through the creation, activation, and execution of procedures for containing the virus, and by creating rules and incentives to influence particular behaviors of peoples. Official communication about the spread of COVID-19 and the implementation strategies for contagion containment provides a pivotal opportunity to examine how the problem(s) and the solution(s) relating to the pandemic are constructed. This study will therefore explore, compare, and analyze definitions of the problems and solutions to the outbreak and spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the speeches made by the heads of state and heads of government in Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden during the pandemic's initial phase.

Our analysis is inspired by Bacchi (2009, 2012) post-structuralist analytical framework for policy analysis. This is a method and theoretical perspective for studying problematizations in political discourse, which will enable us to identify stated problems and corresponding solutions in the speeches and to compare the cases. We first pose the question “What are the “problem(s)” and the “solution(s)” to the spread of the virus represented to be in the communication of the heads of state and heads of government in the four countries included in the study”? Our second question formulates as “What presuppositions and assumptions underlie the representations of the “problem(s)” and the “solutions(s)””? The final question, which builds on the second, reads “Which metaphors are used to describe the spread of the coronavirus and the method for stopping the spread or mitigating its consequences”? The assumption behind this last question is that there is a link between the metaphorical framing of a problem and suggested solutions and interventions—and that this is related to the policy problem/solution complex (cf., Lakoff and Johnson, 2003[1980]). By comparing problem definitions, proposed solutions, and the carrying concepts of the communications and the metaphors used to convey a discursive message, we will finally consider some of the implications that may ensue through the imposition of individual responsibility at the heart of the strategy for controlling the virus.

Communication, Governmentality, and Subjectivities

In this paper we understand the communication undertaken by heads of state and heads of government to address the COVID-19 outbreak and associated containment strategies as a form of science and risk communication: we can therefore expect the communication to include scientific, exploratory, and descriptive messages and objectives that merge with normative goals (cf., Bunge, 1998). While there are differences between these scholarly fields, they also share many common aspects. Risk communication can briefly be explained as the study of public risk perception and expert risk assessment (Sjöberg, 1998; e.g., Pidgeon, 1998) with the explicit aim of changing the public's attitudes (Fischhoff, 1995), while science communication is the practice of enhancing public scientific awareness and scientific literacy (Burns et al., 2003).

Previous studies of science and risk communication outline how communication can make people change their behavior in correspondence with scientific knowledge (Renn and Levine, 1991). Studies show that trust in the actors providing the information is crucial for successful communication (e.g., Slovic, 1993; Kasperson et al., 1999; Löfstedt, 2005), but the procedures and standards for the communication are also important to increase public understanding and acceptance of the message itself (Trettin and Musham, 2000). Kurz-Milcke et al. (2008) stress that the role of communication is to educate and inform a target group about the actual risk(s) and benefits of certain actions, strategies, and policies.

Typically, “risk managers see more data or “working harder” as the best answer to reducing uncertainty” (Kasperson, 2014, p. 1236). This has been a recurrent theme during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic—recall how the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends rapid detection, isolation, testing, and management of suspected cases to “limit the spread of disease, [and] enable public health authorities to manage the risk of COVID-19” (WHO, 2020). This alludes to the Foucauldian debate around spaces of care and spaces of control, which in modern society refers to the care for the well-being and health of larger populaces through the implementation of certain procedures and policies (Foucault, 1977). In our case, this finds a parallel in the WHO recommendation to take epidemiological control over the signs and symptoms of SARS-CoV-2.

The notion of “governmentality” enables us to address how public policy can be productive in terms of promoting particular behaviors. In contrast to more coercive forms of control, governmentality works at a distance by encouraging citizens, individually, and collectively, to take greater responsibility (Rose, 2006); hence, it seeks to shape human conduct in a more subtle way than by mere force (Dean, 2010[1999]). More generally, the concept of governmentality is useful in understanding how policy, through the vehicle of communication, promotes particular knowledge, techniques for regulation, and particular subject positions through the device of what is defined as “good behavior,” or “the conduct of conduct” (Foucault, 1991). This form of governance builds on the idea of what may be termed “responsibilization” and the notion that effective government is indispensably linked to actions of individuals and groups whereby “governing often concerns the formation of the subjectivities through which it can work” (Dean, 2010[1999], p. 71; cf., Raco and Imrie, 2000). Drawing on the concept of governmentality—denoting a form of rule building on the “rational” ordering of human action and affairs—individuals and groups are “governable” through the communication between the state and the public as well as through the technologies and rationalities employed by the state (Foucault, 1991; Sjölander-Lindqvist et al., 2020).

In Foucault's later works (e.g., Foucault, 2007), he developed a distinction between sovereign power (control over territory), disciplinary power (control over bodies), and biopower (power over human existence). More specifically, biopower “represents the confluence of two concurrent interests: concern with the individual body on the one hand, and with the well-being of the population, or species body, on the other” (Maunula, 2017, p. 42). It is important to note that biopower is a form of modern governance related to individualization and the development of a specific relation between the state and the individual (Larsson, 2016). Foucault's concept of disciplinary power is important since the discipline of the body is crucial to the work of biopower (Foucault, 1991). This relationship between biopower and disciplinary power is relevant in comparing and discussing the four countries' national approaches to dealing with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Furthermore, the article takes an interest in how governance regimes create and reform physical space; here, Ingold and his “taskscape” concept (2000) can be useful in understanding how the interaction of bodies in a given landscape—be it urban, recreational, an office, a school, or a factory—lays an important foundation for the considerations made. The bodies and the tasks and activities that unfold in these “taskscapes”—of the family, at the workplace, on the soccer field, or at a café or restaurant—are spaces of both the social and the political (Lefebvre, 1991[1974]; Ingold, 2000). The ways these spaces are used, or in a pandemic and epidemiological repertoire, how the individual and the collective understand and make changes to their social and everyday interactions will be crucial to the prevention and management of the virus.

These performed spaces, constituted by ongoing interactions and negotiations of movements and activities (Dunkely, 2009), are where action is implicated in and operated through relations of power (Foucault, 1991). During the COVID-19 pandemic, limitations on movement have been introduced to combat contagion and the spread of the virus throughout the community. These limitations have not only been applied to public space but partially also to the private sphere, thus providing an interesting antithesis when social interactions, labor, and recreation are construed as potentially risky, and binding individual and collective action and co-presence with the ruling power. In the course of the pandemic, these spaces and the activities are considered as problematic and potentially harmful; they have been reorganized by the articulation of different tactics seeking to bring to light the “flattening-the-curve” goal.

The strategy of flattening the curve strives to avoid over-exhaustion of the healthcare system by slowing down the spread of the virus and diffusing it over an extended period of time. Here, the actions of the individual, i.e., the ability of the state to govern individual behavior, is of vital importance for the government regime to function properly. Drawing on the question of citizen engagement in the political, this also translates into how the individual is an asset who through a sense of civic duty can and should contribute to society. The expectation that the individual, as a pandemic subject, should both consider their own health and the health of others, is premised on the neoliberal values of individual responsibility and the virtue of volunteerism (Maunula, 2017).

The COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden

After the initial outbreak, suspected to have begun and spread from the Huanan seafood wholesale market in the Wuhan region of China (Keni et al., 2020), the virus quickly reached other countries and continents. The four countries included in the study all reported their first cases in January 2020, and in this article, we refer to the initial phase of the spread of the virus when we discuss the addressed problems and solutions. Italy soon became notably hard-hit, with skyrocketing cases of infection and deaths. Spain followed the trajectory of Italy and became toward the end of March 2020 the second-most affected country in Europe. Three weeks into the lockdown, Italy started reporting declines in new cases and deaths. In Spain, infections started to slow down in early April. When compared to Italy and Spain, Germany, the third country included in our study, had a low fatality rate. Sweden, our fourth country, started off relatively slowly in terms of confirmed cases and deaths but soon became among the hardest hit in terms of deaths per capita (www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19-pandemic). In terms of strategies to control the virus and reduce the transmission rate of SARS-Cov-2, Italy and Spain implemented large-scale national, regional, and domestic lockdowns and placed tight restrictions on movement with exceptions for primary needs or professional requirements. Germany's first measures focused on minimizing the expansion of clusters, but soon individual states decided to implement tighter restrictions, including closure of kindergartens and schools and even curfews in a number of cases; other states prohibited physical contact with more than one person from outside one's household. Sweden has consistently taken comparatively milder actions to keep larger parts of society open, with the expressed aim to support the maintenance of the containment strategies over a long period of time. Rather than enforcement and strong lockdowns as was the case for Italy and Spain and to some extent also Germany, the Swedish strategy has largely built on recommendations and advice to maintain levels of hand hygiene and avoid social contacts to reduce the risk of infecting others.

Methodology

The study has been inspired by Souto-Manning (2014) concept of critical narrative analysis, which combines elements from critical discourse analysis with elements from narrative analysis. Souto-Manning subscribes to a definition where emphasis is put on the relationship between linguistic statements and the broader social context within which these statements are made. Her understanding of discourse as something that constitutes “an inherent and inseparable part of the social world, of the broader social context” and that “shapes and is shaped by society” (159) is in line with Fairclough (2001) definition of critical discourse analysis as the “close analysis of texts and relations” (p. 26). Both definitions place the dialectical relationship between texts and other social practices at the center of the analysis.

The term discourse, in a general sense, can be defined as a meaning system or chains of equivalence on a linguistic level; discourse entails ideological perceptions of what is acceptable and appropriate within a specific area, and that hence works to describe and prescribe what can be said and what makes sense within a particular field (Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002). This definition of discourse is employed in the present article. Narrative analysis focuses on speech as a way of making sense of human experience (Souto-Manning, 2014). Within research on policy narratives, actors are known to engage in calculated strategies aimed at exploiting narrative elements to mobilize and support particular policy beliefs (McBeth and Shanahan, 2004; McBeth et al., 2010, 2012). In the present article, narratives are defined as stories through which discourses are described and prescribed.

Combining elements from the narrative method and discourse analysis is well-suited to the theoretical framework of this article, and also answering the questions that we have developed by taking inspiration from Bacchi's problematization framework and the proposition that metaphors by character are situated and pragmatically shaped (Kimmel, 2004). The basic theoretical assumption in Bacchi's approach to policy analysis is that any political discourse includes assumptions and taken-for-granted truths that can be analyzed through a Foucauldian-inspired method of problematization. This approach enables us not only to identify explicitly stated problems and corresponding solutions in the material under study, but also elements that are implicit and taken for granted (Feldman and Sköldberg, 2002).

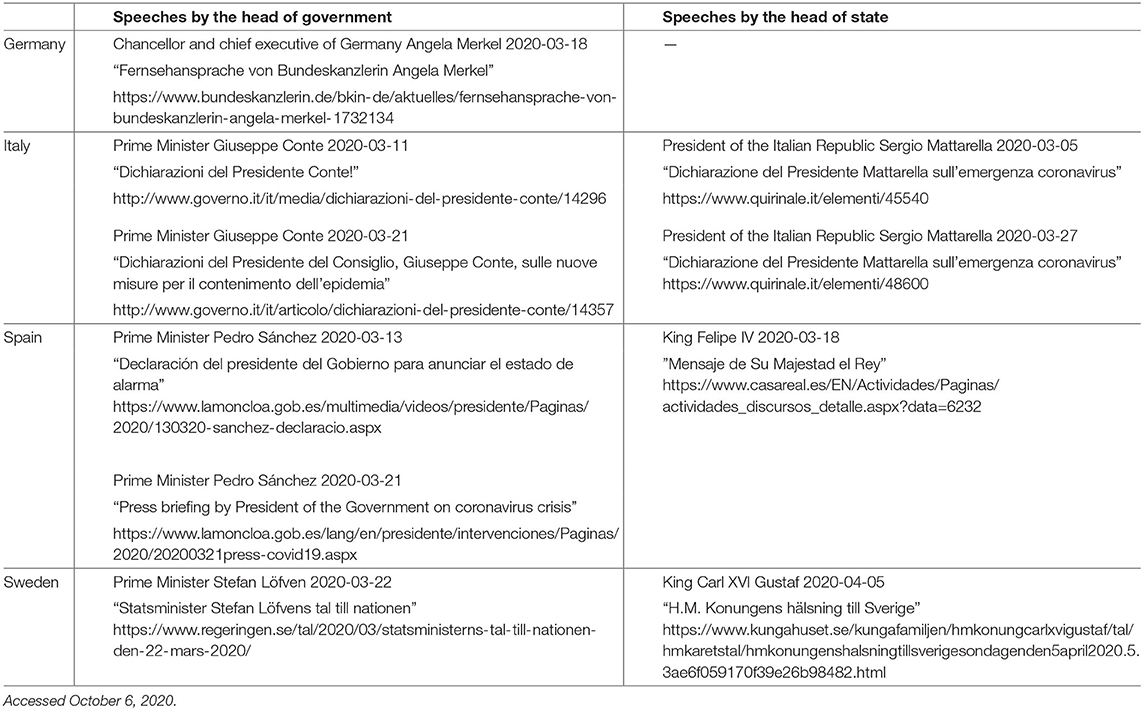

To this end, we utilize Bacchi's approach to structure and compare the logic of the problem- and solution complex in each country and include transcribed formal speeches by heads of government and heads of state directed at the public in order to inform them about the pandemic and governmental actions (Table 1). The German head of state has only delivered one speech on the topic of coronavirus, but since this was not addressed to the nation it is not included for review here. We have chosen to limit our study to March 2020, which in all four countries was the month when the virus outbreak began to spread on a larger scale.

Table 1. List of speeches made by heads of government and heads of state in Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden.

The speeches were transcribed by native or fluent speakers of German, Italian, Spanish, and Swedish (several of the author team are either fluent or commands a first-speaker knowledge in more than one of the four languages), translated into English and analyzed in a reiterative process where the members of the research group continuously added to, read, reread, and discussed their material. A spreadsheet was compiled and circulated within the group of researchers. Information on the speeches pertaining to the Bacchi-inspired questions was plotted in the spreadsheet, which provided the basis for discussions and a structure for analysis of the empirical material.

Problems, Solutions, and Metaphorical Discourse

Germany

The problems as defined in Angela Merkel's speech from March 18 2020, include matters related to the immediate effects of the coronavirus: people getting ill and suffering from the direct consequences of the infection. She stressed that even the best healthcare system can be overloaded if too many patients who are suffering from difficult courses of corona infection are hospitalized within a short period of time. This potential overstrain on medical care is exacerbated by the lack of cures and vaccines against the current virus.

The direct consequences of the virus are not the only problems Merkel talked about in her speech; other problems arising from trying to solve the initial problems of the virus spread are more prominent in the speech. Merkel brings up the consequences of lockdown and social distancing, which she says will dramatically change normality, public life, and social interaction: “Millions of you can't go to work, your kids can't go to school or daycare, theater and cinema and businesses are closed and, what is perhaps most difficult: we will all miss meeting other people.”

The consequences of coronavirus mitigation are also addressed in relation to the business sector when Merkel talks about how the weeks ahead will be challenging for business owners who are struggling to continue, and how their difficulties ultimately pose a threat to the economy at large. The consequences of the lockdown and isolation are not only conceived as threats to the economy and “normality and everyday life.” In Merkel's speech, these precautions are also understood to be a threat to fundamental democratic values. Merkel is consistent in returning to the concept of democracy, a consistency that becomes obvious when she notes that the lockdown has consequences for the democratic self-image of the nation. Merkel highlights freedom of travel and movement as basic hard-fought democratic rights that are under threat because of the actions taken to deal with the coronavirus pandemic. The suggested solutions to the initial problem target both the individual and the collective community, but Merkel also addressed the role and responsibilities of state agents, who should endeavor to make their communication “understandable.” The Chancellor's allusion to the role of the state and government is connected to a fight for democracy and the need to be transparent—in terms of decision-making and communication—to keep the basic democratic values of the state intact.

By referring to the pandemic and the overarching solution with terminology to “defy” and “slow down” the spread of the virus, Merkel made a connection to how effective treatments and a vaccine are yet to be developed but are essential to the containment of SARS-CoV-2. By slowing down the spread we gain time, Merkel said, explaining that time is beneficial for the development of treatments and vaccines, from which follows the goal “that everyone who gets ill can receive the best possible care.”

The solutions formulated in response to these problems put the individual at the center, and include keeping a distance, refraining from handshakes, washing hands with hot water and soap, and following the imposed restrictions on visits to nursing homes for the elderly. The Chancellor also took the opportunity to personalize the crisis by stating, “…it's not only about abstract, statistical numbers, this is about a dad, a grandfather.or a mom, a grandmother….” “I firmly believe that we will overcome this crisis,” Merkel said, framing the issue in terms of solidarity combined with individual compliance:

…that it is up to ourselves, we can support one another—we must be disciplined and follow the rules—we must show that we can act from our heart and with consciousness to save lives.

The solutions targeting the individual clearly build on responsibilization and the idea of self-discipline. The outcome of the pandemic “depends on how disciplined everyone is in complying with and practicing the rules.” Furthermore, “the advice of the virologists is unambiguous” is a definitive statement that closes the door to any further discussion regarding the scientific knowledge presented. This presents a tension in terms of the role and the responsibility of the individual, who on the one hand is responsibilized for her and others' well-being while on the other hand is obliged to do this within the framework provided by the state.

Merkel was careful to address how not only individuals, but also how local communities had to be responsible and aware of the highly precarious situation caused by the virus.

You now hear about wonderful examples of neighborhood communities helping the elderly, who cannot go shopping themselves. I am sure that even more can be done and we as a society must show that we will not leave each other all alone.

There are also measures (said to be necessary) to be taken on a governmental or state level, but these are focused on mitigating the consequences of the response to the coronavirus, to keep the economy running, and to keep the functions of the state intact:

I assure you: The Federal Government is doing everything it can to mitigate and dampen the impact on the economy—and above all to preserve jobs and workplaces. […] We will put in all the measures needed to help our entrepreneurs and employees through this difficult ordeal.

The previous quotation is a reflection of the underlying values, or ontology, guiding the recommendations made by the authorities—it also exposes the way in which they are motivated: Germany is a democracy, and the speech underlines the importance of formulating the guidelines according to the democratic values of the German state. The design of this democratic state is historically rooted: it is a state and a community where every life and human being counts. The Chancellor concluded that the situation for the country is severe and that not since World War II has Germany—as a democratic state—had to meet a greater challenge; it must be met as a united country:

We are a democracy. We do not live under coercion, but by shared knowledge and participation. It is a historical task and only possible to achieve together.

Italy

The President of the Italian Republic stressed in his first address to the nation on March 5 2020, the difficult times facing the country, in particular related to healthcare. Despite the healthcare sector being declared (similar to Germany) “excellent” and “operating with efficiency to the generous abnegation of its staff,” the problem required “the adoption of necessary extraordinary measures” to solve the adversity and to “support the efforts of the healthcare personnel.” President Mattarella articulated, similarly to Prime Minister Conte, a discourse on responsibilization to mitigate the problems caused by COVID-19. President Mattarella invited the individual to be considerate of his/her actions, since the behavior of the individual clearly would have an impact on the capability of Italy to overcome the “emergency.” The President described the crisis as “demanding” and invoked notions of its “defeat;” difficult though they were, these new rules had to be respected and followed in order to overcome the crisis. The need for Italy to unite in a “common sense of purpose” through “involvement, sharing, harmony” was addressed as vital, as was showing “trust in Italy.”

On March 11 2020, Prime Minister Conte delivered a televised statement to the nation, and following up on an institutional statement he had made on March 9, Conte stated: “…I am signing a decree that we can summarize with the expression “I stay at home.”” Conte stated that all public events were banned and that cinemas, theaters, gyms, discos, and pubs would be closed, and funerals, weddings, and sporting events canceled until further notice.

An important focus for Conte in his speech from March 11 was the already fragile Italian economy and the negative impact of the disease on millions of Italian jobs. He invoked a sense of sacrifice by the Italian people and alluded to their capacity to overcome difficult situations through responsibility, pride, nationhood, and a sense of community: “Italy, we can say it loudly, with pride, is proving to be a great nation, a great community, united and responsible.” Italian citizens must be safeguarded, in particular the vulnerable and fragile. He implied the necessity to be patient, and that the Italian people had “to remain firm, clear, and responsible.” Even if people had to remain apart now they would be able to “embrace each other more warmly” in the near future and “Together, we will do it.”

Conte furthermore stressed how Italy is a positive example for the rest of the world, a source of inspiration and a country whose joint actions swiftly combated the virus through strict rules and resistance:

At this moment, the whole world is certainly looking at us for the numbers of the contagion, they see a country that is in difficulty, but they also appreciate us because we are showing great strictness and great resistance. I have a deep conviction. I would like to share it with you. Tomorrow not only will they look at us again and admire us, but they will take us as a positive example of a country that, thanks to its sense of community, has managed to win its battle against this pandemic.

On March 21, the Italian Prime Minister announced that the government had decided that any “production activity that is not strictly necessary, crucial, and indispensable to guarantee us essential goods and services” would close to prepare for the most acute phase of the infection and “contain the spread of the epidemic as much as possible.” Conte assured transparency and the presence of the state in this emergency, which now also had, as expected, turned into “a full economic emergency.”

In this time of extraordinary crisis Conte called for self-reflection and stressed the importance of continuing the struggle, to be patient, resistant, responsible, and show confidence in the measures taken by the government, encouraging people to stay put since “even this, we hope soon, will be finished.” Underlining the efforts of the doctors, nurses, the police and armed forces, supermarket clerks, and those infected and struggling for their lives in hospitals, the sacrifice required of the individual was minimal, he said while alluding to how the community had become more tightly linked, as “a chain to protect the most important asset—“life”: “We are giving up the most expensive habits, we do it because we love Italy, but we do not give up courage and hope in the future. United we will do it.”

It was stated that Italy was experiencing the most difficult crisis since the post-war period and that this would be imprinted in the collective memory of the people. This reference to history and the hard times brought on Italy during and after World War II was also featured in Merkel's speech. Everyone, according to Conte, had to make their contribution to overcoming this challenge, represented by the “death of many fellow citizens.” The loss of lives was not only about “simple numbers”: it had a symbolical meaning in the sense that the deaths represented the “values which we grew up with” and by notifying the “stories of families who lose their dearest affections,” Conte alluded to the importance of intergenerational building of meaning and identity creation.

In an address to the nation on March 27 2020, the President of the Republic did also build on the notion of hardship when he stated how the situation in Italy was “a grim period in our history” and how the epidemic had caused a “pain of loss.” Mattarella made a subtle bridge over to how the presence of the virus had consequences for the individual's freedom to exercise his or her religion: “the impossibility of commemorating their parting from the communities to which they belonged, as we ought to.” This reaffirmed the role the individual plays in the collective, and how people get to know who they are by commemorating family and community members. The main theme in the second address was gratitude, demonstrating how the Republic not only recognizes the importance of remembrance but also how the state and the Italian president applaud the work and generous commitment to society of the “medics, nurses, and the health workforce in its entirety,” especially if they had themselves become “victims” in the defeat of the virus. Other parts of the Italian government were also recognized for contributions that had made it possible not only for societal life to continue but also the practical, day-to-day work of the Republic. However, as he said, the future of the Italian economy and the labor market were not easily handled but he stated again the importance of unity and asserted that the Republic would take care of the people.

By cherishing the changed behavior of “the vast majority of our people,” the Italian President also noted how the acts of the individual were a sign of citizenship. Individual and collective sense of responsibility had to continue. This, the President explained, “is the most essential resource that a democratic state can rely on in the moments we are facing.” He continued that the collective response of the Italian people was admired abroad, and took the chance to point to a sense of commitment amongst heads of state in Europe and beyond. Their expression of “their closeness to Italy” was a demonstration of how Italy had served as a role model in this emergency. Through his statement that the European Union, the Central Bank of Europe, and the European Commission with the support of the European Parliament had “taken significant and positive financial and economic decisions,” he noted that “common initiatives are indispensable,” and by saying that the “reality of the dramatic conditions our Continent is withstanding” he vindicated the solidarity at a European level which was required to beat the threat.

Spain

On March 13 2020, the President of the Spanish government—Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez—notified the country in an institutional statement that he had informed the head of state that the Council of Ministers would the following day decree a state of emergency throughout Spain for the next 15 days. The day after, the Prime Minister addressed the nation in a televised speech to announce the conditions of the emergency. Sánchez described the virus as a public health problem, which despite “a robust health system with excellent and extraordinary professionals” and an “action plan,” required an approach that would face it as “a problem that affects us all.” He also called for regional unity to overcome the crisis.

The central government of Spain turned to the constitutional system to provide a base of action in order to solve the extraordinary circumstances arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. On March 13, he had explained how this situation “provides the government of Spain with extraordinary legal resources to respond with.” What is required, he stated, is “a raft of exceptional decisions” to “mobilize all the resources of the state as a whole to better protect the health of all citizens.” To solve this “extraordinary crisis,” resulting from a too rapid spread of the virus and the consequential effects on society, Sánchez said that action required an approach that would:

…protect all our citizens, particularly those that are most vulnerable to the virus due to their age or other already existing conditions, and also to respond to the social and economic emergency as quickly and forcefully as possible.

There are “some very tough weeks ahead of us,” Sanchez said and asked—similar to the pleas made in Italy and Germany—for joint action, individual responsibility, and social discipline but did also point to the important support of the national and regional health authorities, which should “provide the professionals with the resources to carry out their work and maintain and reinforce the extraordinary coordination they have implemented over these last few weeks.” He emphasized the need for coordination, protection, and unity to “defy” and “combat” the pandemic. In this address the Prime Minister did not announce any particular policies or restrictions other than pointing to the emergency as merely a sanitary emergency, even though the coming announcement of a state of alarm meant that restrictions were to be adopted.

The Prime Minister addressed the role of the individual in coping with the crisis forced upon Spain but also alluded to the healthcare professionals in terms of them being in the “frontline,” as the “shield” between the virus and the people of Spain. Their need for commitment and sacrifice as the means to overcome the crisis should be recognized by everyone. The Prime Minister also stated that in addition to “a personal duty” to maintain distance both physically and socially, the individual also had “maximum” responsibility to follow the advice and recommendations of the experts. To mitigate this hardship and the burden on healthcare, elderly people, and people with chronic diseases should recognize their responsibility to “protect themselves” to the “utmost degree,” which they could do by avoiding “contact and exposure in public spaces at all costs.” Young people were contracted to play a “decisive” role in “halting the contagion,” and they should not feel protected from the worst effects of the virus because of their youthful vitality. They should be aware that “they can transmit it [the virus] to other far more vulnerable people around them” and should therefore “limit their social contact and keep their distance.” This passage had a clear collective connotation when it was explained that the people of Spain had to work together, as they were in a tough and difficult conflict with SARS-CoV-2—the enemy that must be defeated:

Victory depends on us all, in our homes, with our families, at work and in our neighborhoods. Heroism also consists of washing our hands, staying at home and protecting ourselves, which means protecting the rest of our compatriots.

The idea of the containment as a battle returned in the national address on March 14 when Conte explained that the “objective is to stop the spread of the virus and to eliminate it.”

As in the case of Germany and Italy, the solutions targeting the individual build on responsibilization and the idea of discipline, but it is also clear that Spain, as a state, has a clear role and responsibility: “the government of Spain will do whatever it needs to, whenever and wherever it needs to.” Similar to Italy, overcoming the emergency would require many state resources (including army resources). Ultimately however, and similar to Germany and as we will see, also Sweden, unity, respect, and responsible individuals and collectives (families, young people, etc.) would be the decisive factors.

Four days after Sánchez's address to the nation, the head of state King Felipe VI made a national address in which he presented the problem as a sanitary crisis with repercussions for the general welfare of the Spanish state and society. He discussed the crisis as a challenge to people, “not only in Spain but throughout Europe and the rest of the world.” When he alluded to the seriousness of the crisis and its unprecedented character, the King suggested that the defeat of the virus through committed and responsible citizens would make society stronger and united, despite the negative consequences of the virus for society and the individual.

In addition to the King referring to science and expert advice as crucial dimensions in overcoming the health crisis, he also recounted how the crisis was a reality that would test the Spanish people and their society. Even if the test could be “difficult, painful, and sometimes extreme,” the current situation would show both the virtues of Spanish society and the capacity of the state to deal with this difficult situation. The spread of the coronavirus “won't beat us,” the King said. It would on the contrary, “make us stronger as a society; a society that is more committed, more supportive, more united.”

On March 21 2020, the head of government spoke of the virus outbreak as “the worst forecast” ever and that “truly catastrophic scenarios” were approaching—the effects of this, the “worst health emergency in the last century.” Sánchez pointed to the unprecedented character of the COVID-19 virus as it had turned out to be more widespread than normal flu, ominously adding that “it is also more lethal,” seeking to build an image of the deadly serious character of the virus. He referred to the course of the crisis caused by the virus and focused on how the last 7 days had transformed the social landscape. He celebrated the whole of Spanish society, saying:

…the way we view our neighbors, we now have a closer attachment to our neighbors, they share our fears and the yearnings from the balconies at 8 o'clock have made them familiar, they are no longer strangers who are barely greeted.

…[those who] serve us in shops, those who produce the goods we consume from distant locations, those who maintain the communications that keep us connected, those who supply the energy that lights our homes.

As in his institutional declaration on March 13, the Prime Minister picked up on concepts associated with military battle in terms of solutions; he said how “we are fighting an enemy that we will defeat” through getting to know it better—and, “as we get to know this virus better, the way we fight it will change to become more effective.” He also stressed how Spain had aimed at applying measures that were effective from a health perspective and with the least possible consequences for people's social lives and the economy. Efficacy of government action, he explained, was a fine balance between social distancing, the maintenance of economic activity, and the protection of individual rights. The solution to the impact of the pandemic was to be found in the allocation of resources to the health sector, and in showing strength even if the Spanish people suffered socially in hindering the “unprecedented” consequences following the virus outbreak. The “most socially vulnerable” had to be protected, while essential supplies, such as electricity, water, housing, and a minimum level of income, had to be guaranteed.

Sweden

The Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, in his speech on March 22 2020, urged the individual citizen to take action and show responsibility. Based on the rhetorical framing device that lives, health, and jobs are at stake because of the coronavirus, and with a personal and “you”-oriented phrasing style, he explained that many will contract the virus, and that this provided a basic problem for society since it would affect the adaptive capacity of healthcare. The goal of the government is to limit the spread of the virus so that not many people will become ill at the same time and to ensure adequate resources for the healthcare system. An overarching problem of the pandemic is here associated with the Swedish healthcare system's ability to cope with the demand for care, and, in particular, the protection of vulnerable groups, primarily older people. In Sweden, ran the Prime Minister's speech, the solution to this problem is the individual and the willingness of the individual to follow the recommendations made by the government and the responsible agency: “The only way we can cope with this is that we approach this crisis as a society where everyone assumes responsibility, for his- or herself, for one another and for our country.”

According to the Prime Minister, the pandemic “will go on for an extended period of time,” and eradicating the virus is simply not an option. In contrast to Germany, Italy and Spain, Löfvén stated it as crucial to learn to live with the virus. The Swedish strategy therefore, focused on the implementation of measures that the individual could uphold over an extended period of time. Since a society can only remain under lockdown for a limited amount of time, a lockdown was not perceived as a sustainable measure for managing the outbreak of the virus. The tools and measures used to achieve this are mainly recommendations and guidelines aimed foremost at individuals from the Public Health Agency of Sweden; in some, albeit fewer, cases, regulations are also used. The general recommendations given are to stay at home when experiencing even mild symptoms, practice social distancing while out in public spaces, and wash hands with soap and water frequently. It is strongly asserted that it is every individual's responsibility and duty to follow the guidelines from the authorities. To do so is to show solidarity, said the Prime Minister in his speech, ultimately stressing individual responsibility, and how Swedish society and its famous welfare system rests on a contract of trust between the government and the citizens:

I am convinced that everyone in Sweden will take their responsibility. Do their utmost to ensure the health of others. To help each other and thus be able to look back at this crisis and be proud of your very role, your efforts for your fellow human beings, for our society, and for Sweden. […] None of us can take a chance. None of us can go to work with symptoms. Young or old, rich or poor, does not matter. Everyone needs to do his or her part.

A secondary problem brought up in the Prime Minister's speech was the knock-on effect on the Swedish economy. Employers and employees, employer organizations and employee organizations were in the speech considered essential to society, and each and every one of them is also a citizen and part of Swedish society. The Prime Minister averred that in these tough times he sought to relieve the consequences for those who are working and for Swedish companies.

The two speeches made by His Majesty King Carl Gustav XVI focused largely on the spread of the virus and the possible consequences of an infection to people's health. However, problems related to travel restrictions and lockdowns are addressed as a threat to people's livelihood, businesses, work opportunities, and the Swedish economy. “The pandemic is also hitting companies, jobs, and the Swedish economy hard; indeed it hits the entire Swedish society,” the King said on April 5 2020. While the speech by the Swedish Prime Minister is decidedly secular, the second speech by the King, given just before Easter, has several religious references and addresses restrictions of religious services as a problem associated with the corona outbreak. His Majesty said in the same way as the Prime Minister how the solution to the problem is primarily a matter for the individual, and so individuals were asked to refrain from doing things that they have looked forward to doing. The King appealed to people's moral responsibility: “Did I think of my fellow humans? Or did I put myself first? The choices we make today we will live with, for a long time,” and urged the individual to listen to the recommendations of the responsible authorities and to refrain from gathering together. The speeches also state that industry and government are important actors in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is not clear from the speeches if this is related to stopping the spread of the virus or to mitigating the consequences of the implemented restrictions. While the nation, the country, and Swedish society are referred to as being under threat due to the pandemic, the speeches do not specifically address what aspects of these three elements are under threat and in what way.

Discussion

The actions taken by the four countries to mitigate the coronavirus build on the establishment of an assemblage of different elements and metaphorical framings that each contribute to the configuration of problems and solutions. According to Lakoff (2015), an “assemblage” is a domain connoting the values and forms of individual and collective experience and existence that are at stake. In our case, we see how this domain includes statements regarding the uncertainties of the coronavirus and the risk it poses to public health and the ability of the healthcare sector to cope with infected people. The discourse presented also includes statements regarding risks to economy, nationhood, and ultimately democracy. Another vital message is how the individual but also the collective are both a problem and the solution in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Following Foucault's governmentality approach, the solutions presented build on an ensemble of different institutions and procedures directed at containment, but we also see how these far-reaching tactics and the success of them, are said to be relying heavily upon and determined by the actions of the individual.

The communication of the strategies undertaken by heads of state and heads of government legitimizes the interventions implemented; those speaking do this by using different frames, particular conceptualizations, and generalizing assumptions to build meaningful syllogisms. Our four cases show how the heads of government and heads of state have addressed their nations to not only inform about the coronavirus outbreak, but also to explain the restrictions and interventions planned and implemented by the state; and these speeches consequently become a part of the strategy implementation. Our analysis and comparison leaves us with both similarities and differences in the ways the heads of state and heads of government conceptualize the containment interventions and strategies. One striking similarity regards how the communication includes the motivation of both individual action and non-action, both in fact argued necessary to contain the COVID-19 virus. This operates through a responsibilization discourse in which the individual body is conceptualized as a central agent, one whose practices—be it hand sanitization or keeping socially distant from the elderly—are framed as crucial to overcoming the crisis brought onto the different countries through the spread of the virus.

The individual is also important as part of and due to her/his effect on the collective. We see how the collective is appreciated in the speeches; healthcare personnel are highlighted as vital to the containment of the virus, and volunteerism is mentioned to exemplify how the individual as part of the collective can make containment possible. Whereas, the concept of collective action is usually associated with the governance and management of natural resources (Ostrom, 2000), we see an analogy here in terms of the debate about whether a self-interested person would actually choose to contribute to the public good (Olson, 1965), and also Ostrom's dispute with Olson's (1965) and Hardin (1971) idea of the prisoner's dilemma and the choice between selfish behavior and social altruism. Ostrom held that “the world contains multiple types of individuals, some more willing than others to initiate reciprocity to achieve the benefits of collective action” (Ostrom, 2000, p. 138). This brings the role of the individual in relation to the collective good into sharp light (as we see in other issues as well, for example is individualization of responsibility a recurrent frame in the mitigation of climate change). Our study shows how responsibility and sacrifice of the individual are said to determine the collective's capacity to react to and overcome a difficult situation. The Italian leadership, for example, brings the virtues of responsibility, pride, nationhood, and sense of community into their communication. The German Chancellor frames the issue in terms of solidarity combined with individual compliance with recommendations and rules for social interaction, and the Swedish Prime Minister embraces individual endurance and personal responsibility as central to society's coping ability. Following the advice and recommendations are “a personal duty,” says the Spanish Prime Minister.

Our findings display the shift in the social contract in many European countries over the last few decades depicted by Soysal (2012), according to which a greater emphasis has been put on “active citizenship.” Italy makes a connection between individual behavior and citizenship through evoking the notions of “people” and “nationhood,” and that the pandemic is a threat to the Italian national territory. In Sanchez' and Löfven's speeches we find how the citizens are acknowledged as part of society. In the German and Italian speeches historical references are made to install a sense of community, and they all embrace the notion of active citizenship through pointing to the role the individual plays for the common good. In the Swedish speeches however, the historical context is largely absent; the pandemic is instead framed in relation to the life of the individual in the present where the choice to do the right thing can be made.

The speeches analyzed can be understood as governance technologies in line with Foucauldian scholarship; the spatial disciplining and self-governance demanded by the regimes create subject positions for individuals or groups by advocating hand sanitation, self-isolation, social distancing, and other containment strategies and protocols, which are purposely implemented to slow the spread of the virus. The subject position could be the employee who works from home, the regular gym visitor who organizes a workout place in the garden, or people who on a voluntary basis buy groceries for elderly neighbors or poor families. Through invoking a sense of responsibility, sacrifice, and current life under the influence of the Corona pandemic as a difficult time for everyone, the speeches allude to how people through changed behavior can, and should, contribute to the greater good. The communication posit actions, strategies and policies, which are embedded in ideological and world view-shaped conceptual frames (cf., Lakoff and Johnson, 2003[1980]; Underhill, 2011). The heads state the need to change life in order to slow down the spread of the virus. Our results show how the countries' containment strategies depend on the individual's willingness to support the collective gain—the individual is a key cause of, and solution to the problem. However, construing the individual as an indispensable actor to overcoming the crisis also means that the individual is laid open for reprehension—we see evidence of this in the speeches when the ethos of conduct is attached to the individual through inspiring a sense of responsibility (cf., Foucault, 1991).

However, in the context of the countries included in this study, we find resistance toward the strategies when people skirt confinement orders and refuse to comply with social distancing rules—going to “Corona parties” as was reported in the German case (Al-Jazeera, 2020; Washington Times, 2020), or the YouTube-published footage of a man who took a run along an Italian beach despite prohibition (YouTube, 2020). This non-embracement of the guidelines and rules for individual behavior goes hand in hand with a Foucauldian understanding of the resistance at the capillary level of power execution and refers both the idea of disciplinary power and the taskscape concept. Skirting orders is an act of resistance, a refusal to be a subject of discipline, surveillance, and ranking. This political act begs us to ask how well-being is produced, for whom, and what factors makes certain communication less prone to be rendered meaningful for certain groups. A study by Campbell et al. (2001) demonstrates how compliance or non-compliance with advice is a reasoned response in relation to a person's perception and assessment of the effectiveness of the intervention, and the willingness to make changes to her/his daily life if the action asked for is understood to affect the everyday life in a negative way. Acts of resistance can also be related to studies in risk communication where it has been shown how communication intended to increase knowledge and change behavior might instead lead to polarization and the reinforcement of boundaries between the public and experts (Wynne, 1992). This may worsen if there are conflicting views on the matter in question (Earle and Cvetkovich, 1995). The information that underlies the communication might have a high degree of uncertainty due to lack of previous research, conflicting results in previous studies, or—as have been particularly evident in the current pandemic—conflicting views and interpretations of scientists from different fields of research and disciplines (e.g., Dagens, 2020). Debates and conflicting views per se are not a problem [from a democratic perspective it is rather the contrary; see, e.g., Laclau and Mouffe (2001)], but a lack of unanimity may possibly increase existing polarization and lead the individual to neglect advice, guidelines, and regulations (Sjölander-Lindqvist, 2020). From risk communication research, we have learned the important and problematic role of trust for scientific advice to be received well by its recipients, which means that it is important to build individual willingness to engage in preventive or emergency behaviors proposed by an authoritative agent (Jasanoff, 2007; Cairns et al., 2013). A lack of knowledge may be inherently distortive as suggested by Al-Hanawi et al. (2020), who note that the low level of knowledge among the public about the pandemic and the virus may lead to non-compliance with guidelines and recommendations. The high level of uncertainty regarding the disease itself and the effectiveness of different strategies to combat its spread may distort the message (Lundgren and McMakin, 2018).

Furthermore, competing discourse, such as conspiracy theories or religious narratives, might also distort a message or help create the conditions for disobedience (Ahmed et al., 2020; Depoux et al., 2020). An example in this specific case is a popular belief that God will protect those who have sufficient faith, as was the case in Brazilian neo-pentecostal churches (Capponi, 2020). These might be reasons as to why the role of science, and trust in science, are emphasized in the speeches (Slovic, 1993; cf., Kasperson et al., 1999; Löfstedt, 2005). The Swedish Prime Minister points to the importance of endurance since it is a novel virus and the German Chancellor talks about the current lack of cures and vaccines. In the meantime, to control spread and make containment decisions, WHO (2020) has pointed out that it is “important to understand longer-term trends in the disease and the evolution of the virus.” This dimension is rarely noted by the leaders in their speeches; the role of science is instead related to the issue of a cure more than how epidemiological surveillance can track the spread of contagion. Focus lies more in controlling movement through either lockdowns (as in the case of Germany, Italy, and Spain) or through inspiring individual willingness to stay at home as much as possible (Sweden). In both cases, action is implicated in and operated through relations of power (Foucault, 1977) but also through relying on an existing trustworthy relation between the governor and the governed.

To facilitate the spread of a message and to support individual understanding of overt risk, communicators should map out the situation using conceptual models (Covello et al., 2001). This is reflected in the ways the heads of state and heads of government conceptualize the pandemic as a war to be fought. In addition to putting the healthcare sector and science in the frontline of the “battle” to “defeat” the virus and pronouncing responsibility and sacrifice (cf., Bates, 2020), the heads augment the importance of responsive actions to the current crisis with ideas of citizenship and inspiring a collective sense of belonging. The Italian leaders talk about how Italy, through the Italians' love for their country and the nation, has shown the rest of the world their capacity to respond swiftly to a crisis despite the suffering caused by the virus. This shows how the collective, and collective values, serve as a rhetorical model for individual action. Where in Italy and to some extent Spain they talk about nationalism and the love of country as a motivation for individual action, this is not highlighted in the Swedish and German speeches. In the Swedish case, the nation is less explicit. This can be understood to reflect historical differences in views on how a society functions, of what creates cohesion and binds a society together, and the role and acceptance of nationalistic discourses. For example, the leadership in all cases takes the opportunity to embrace the important role of the national government in controlling the outbreak. This is particularly salient in the speeches by the Spanish Prime Minister and the Spanish King, who both propose the need to mobilize the resources of the state to protect the citizens and how governments are ready to make exceptional decisions. At the same time, people must patiently be ready to change their lives. This reflects how solutions to the initial problem target both the individual and the collective national community, and the important supervising role of the state and its agents.

Italy brings up the importance of European cohesion, narrated in terms of the importance of collective action based on the idea of solidarity. This should be seen against the exhaustion of the economy due to the implementation of society lockdowns. However, the shutdown of national borders remains relatively unnoticed in the speeches. This is interesting since the core of the European Union is stipulated as the freedom of movement of people, goods, services, and capital. The differences between national strategies within the EU and the fact that the problem related to closing is not more prominent in the speeches indicate that individual nations understand the virus and the consequences of the virus as a problem to be addressed on a national level—rather than on a joint European level.

As seen, there are distinct differences in the national responses to the pandemic. While differences in national regulation and the institutional division of roles and responsibilities in each country, respectively, influence the national strategies, the different approaches can also be understood as differences in governing techniques. While a discourse on biopower is evident in all the national cases there are differences in how this power is executed and what rhetorical figures and methods are employed to regulate the population. The measures based on cohesive force and prohibition can be understood as forms of disciplinary power—executing direct power over human bodies whereas, say, the Swedish approach of pleading for the responsibility of the individual is rather a method that more radically relies on biopolitical power and control over populations. Following Rose (2006), the individual and social body becomes “a vital national resource” (p. 144). In terms of Foucauldian scholarship, the containment strategies implemented are therefore a style of governmental control envisaged to reorganize social relations, which takes shape through regulated schemes for actions. The individual is assumed to take co-responsibility for her or his actions and to operate and live her or his life within a new regulated space to avoid further spread of virus, since the actions, and social relations, of individuals are considered incontestably risky to public health. Indubitably, COVID-19 shows that people “are all connected, both by the microbial and interpersonal vulnerabilities that always haunt us and by the social and collective care infrastructures that could minister to heal broken bodies” (Kochhar, 2020, p. 73).

The German Chancellor points to how the virus and the measures implemented to prevent its spread might not only negatively influence the economy—as all the heads of government and heads of state agree—but also present a threat to fundamental democratic values. Ingold (2000) taskscape idea can be useful here since it provides the opportunity to devote attention to how the prevention of further spread of the coronavirus affects the opportunities for the individual to pursue social relations and undertake activities, both in the public and the private. Through the individualized regulations and recommendations to contain the spread of the virus, the individual's very home and private space also becomes a taskscape. The individual's actions, and the possible effects thereof, are connected to the collective of society at a distance. This, in turn, had impact on both the personal and collective production of meaning when German, Italian, and Spanish residents were stripped of their right to go to church, take a run, or meet extended family members. This reaffirms the individual-collective relationship but also how the building of meaning is an inherently social practice. On the other hand, changes to life and social relations had new configurations when the containment situation led to other kinds of collective acts; as, for instance, when people volunteered to help their fellow community members by shopping for groceries or picking up medicine from the pharmacy.

Clearly, the solutions to the problems of public health arising due to the COVID-19 pandemic place the body, and the movements and the network of the social relations of the body, at the center. The strategies of containment are both dynamic and embodied as there is a clear focus on mastering individual movement, but also contextual since the four countries label their containment strategies somewhat differently. The leaders pronounce to some extent different concerns developing from how solutions to problems can lead to new problems. Or, to put it another way, some uncertainties can be reduced with the implementation of spatial disciplining and self-governance tactics, but this may lead to new uncertainties and new gaps in knowledge when value issues (pertaining to, for example, the economy or justice) inform the identification of uncertainty, making decisions on course of actions no less problematic (Dietz, 2013).

Conclusions

By comparing the communication of political/constitutional leaders in Italy, Germany, Spain, and Sweden, we have found how the solutions to the problems caused by COVID-19 pandemic are strongly constituted and defined by epidemiological considerations through which health and well-being to a large extent have become the antithesis: social interactions and recreational activities should as much as possible be avoided, or even forbidden. These politics place the body at the center of events and the interaction of bodies in a given landscape—be it urban, recreational, an office, a school, or a factory—as the problem. All of these are landscapes of interaction, based in relations and constituted by the material world, and these are the spaces where movements are renegotiated and restricted, and where limits of movement are introduced to combat contagion and spread in the community. This includes public space but also the private sphere when we are given advice to wash our hands thoroughly after returning home from the risky outside or to quarantine from our family members in case of infection.

The analyzed speeches showcase the relationship between disciplinary power and biopower as depicted by Foucault, with the controlling of the body serving as a way to control, and having far-reaching implications for, human existence. The communication by the heads of state and heads of government hinges on the tenet of how the individual citizen is assigned a significant role and is deemed a carrier of responsibility for preventing further spread of the virus. While the German case clearly addresses the relationship between democracy and limits of rights, for most of the other countries such an issue was exempt. This throws into question the unsettling connection between individual autonomy as a democratic right and disciplinary mechanisms, sometimes phrased encouragingly and at other times in an enforcing way. It should give us pause for thought that whereas the (laudable) goal of state action has been to produce corona-free spaces, human, and democratic rights have been fenced-in.

Another fundamental dimension is how the ways the leadership in the four countries inform about and explain the containment strategies coincide. Exploring the framing we see how the messages attempt to be meaningful “via symbol-to-word correspondences” (p. 173). In this perspective, the communication—following the logic of posing the problem and describing the solutions through the articulation of a discourse in which the individual body is apprehended as a basis for the spatial specifications of strategy—push us toward an understanding of how risk communication is a part of governance technologies.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

AS-L, SL, NF, and NG: conception and design of study. AS-L, SL NF, NG, CM, and SC: analysis of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approval of the version of the manuscript to be published, and main responsibility for acquisition of data. AS-L, SL, and NG: drafting the manuscript. AS-L: coordinating role. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Ahmed, W., Vidal-Alaball, J., Downing, J., and López Segu,í, F. (2020). COVID-19 and the 5G conspiracy theory: social network analysis of twitter data. J. Med. Internet Res. 22:e19458. doi: 10.2196/19458

Al-Hanawi, M. K., Angawi, K., Alshareef, N., Qattan Ameerah, M. N., Helmy, H. Z., Abudawood, Y., et al. (2020). Knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19 among the public in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 8:217. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00217

Al-Jazeera. (2020). Germany: Will Authorities Crack Down on ‘Corona Parties’? Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/germany-authorities-crack-corona-parties-200319205701825.html (accessed July 20, 2020).

Bacchi, C. L. (2009). Analysing Policy: What's the Problem Represented to be? London: Pearson Education.

Bacchi, C. L. (2012). Why study problematizations? Making politics visible. Open J. Political Sci. 2:1. doi: 10.4236/ojps.2012.21001

Bates, B. R. (2020). The (in)appropriateness of the WAR metaphor in response to SARS-CoV-2: a rapid analysis of donald J trump's rhetoric. Front. Commun. 5:50. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.00050

Bunge, M. (1998). Social Science Under Debate: A Philosophical Perspective. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Burns, T. W., O'Connor, D. J., and Stocklmayer, S. M. (2003). Science communication: a contemporary definition. Pub. Underst. Sci. 12, 183–202. doi: 10.1177/09636625030122004

Cairns, G., de Andrade, M., and MacDonald, L. (2013). Reputation, relationships, risk communication, and the role of trust in the prevention and control of communicable disease: a review. J. Health Com. 18, 1550–1565. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.840696

Campbell, R., Evans, M., Tucker, M., Quilty, B., Dieppe, P., and Donovan, J. L. (2001). Why don't patients do their exercises? Understanding non-compliance with physiotherapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 55, 132–138. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.2.132

Capponi, G. (2020). Overlapping values: religious and scientific conflicts during the COVID-19 crisis in Brazil. Soc. Anthropol. 28, 236–237. doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.12795

Covello, V., Peters, R., Wojtecki, J., and Hyde, R. (2001). Risk communication, the West Nile virus epidemic, and bioterrorism: responding to the communication challenges posed by the intentional or unintentional release of a pathogen in an urban setting. J. Urban Health 78, 382–391. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.382

Dagens, N. (2020). DN Debatt: Folkhälsomyndigheten har Misslyckats – nu Måste Politikerna Gripa in. Available online at: https://www.dn.se/debatt/folkhalsomyndigheten-har-misslyckats-nu-maste-politikerna-gripa-in/ (accessed July 30, 2020).

Dean, M. (2010[1999]). Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society, 2nd edn. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications).

Depoux, A., Martin, S., Karafillakis, E., Preet, R., Wilder-Smith, A., and Larson, H. (2020). The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Travel Med. 27:taaa031. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa031

Dietz, T. (2013). Bringing values and deliberation to science communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 14081–14087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212740110

Dunkely, C. M. (2009). A therapeutic taskscape: Theorizing place-making, discipline and care at a camp for troubled youth. Health Place 15, 88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.02.006

Earle, T. C., and Cvetkovich, G. (1995). Social Trust: Toward a Cosmopolitan Society. Westport: Praeger.

Fairclough, N. (2001). “Critical discourse analysis,” in How to Analyse Talk in Institutional Settings, eds. A. McHould and M. Rapley (London: Continuum), 25–38.

Feldman, M. S., and Sköldberg, K. (2002). Stories and the rhetoric of contrariety: subtexts of organizing (change). Cult. Org. 8, 275–92. doi: 10.1080/14759550215614

Fischhoff, B. (1995). Risk perception and communication unplugged: twenty years of process. Risk Anal. 15, 137–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb00308.x

Foucault, M. (1991). “Governmentality,” in The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality: With Two Lectures by and an Interview with Michel Foucault, eds. G. Burchell, C. Gordon, and P. Miller (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 53–72.

Foucault, M. (2007). Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-1978. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Foucault, M. (2010). The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-1979. New York, NY: Palgrave McMillan.

Giallonardo, V., Sampogna, G., Del Vecchio, V., Luciano, M., Albert, U., Carmassi, C., et al. (2020). The impact of quarantine and physical distancing following COVID-19 on mental health: study protocol of a multicentric Italian population trial. Front. Psychiatry 11:533. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00533

Hardin, R. (1971). Collective action as an agreeable n-prisoners' dilemma. Science 16, 472–81. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830160507

Jasanoff, S. (2007). Technologies of humility: citizen participation in governing science. Nature 450:33. doi: 10.1038/450033a

Kasperson, R. (2014). Four questions for risk communication. J. Risk Res. 17, 1233–1239. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2014.900207

Kasperson, R., Kasperson, J. X., and Golding, D. (1999). “Risk, trust, and democratic theory,” in Social Trust and the Management of Risk, eds. G. Cvetkovich and R. Löfstedt (London: Earthscan), 22–41.

Keni, R., Anila, A., Ganesh, N. P., Jayesh, M, and Krishnada, N. (2020). COVID-19: Emergence, spread, possible treatments, and global burden. Front. Public Health 8:216. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00216

Kimmel, M. (2004). Metaphor variation in cultural context: perspectives from anthropology. Eur. J. English Stud. 8, 275–294. doi: 10.1080/1382557042000277395

Kochhar, R. (2020) Disability and dismantling: four reflections in a time of COVID-19. Anthropol. Now 12, 73–75. doi: 10.1080/19428200.2020.1761213.

Kurz-Milcke, E., Gigerenzer, G., and Martignon, L. (2008). Transparency in risk communication: graphical and analog tools. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1128, 18–28. doi: 10.1196/annals.1399.004

Laclau, E., and Mouffe, C. (2001). Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

Lakoff, A. (2015). Real-time biopolitics: the actuary and the sentinel in global public health. Econ. Soc. 44, 40–59. doi: 10.1080/03085147.2014.983833

Larsson, S. (2016). Att Bygga ett Samhälle vid Tidens Slut: Svenska Missionsförbundets Mission i Kongo 1881 Till 1920-Talet. (Ph.D. Thesis), University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Lundgren, R. E., and McMakin, A. H. (2018). Risk Communication: A Handbook for Communicating Environmental, Safety, and Health Risks. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & IEEE Press.

Maunula, L. (2017). Citizenship in a Post-Pandemic World: A Foucauldian Discourse Analysis of H1N1 in the Canadian Print News Media. (Ph.D. Thesis), University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Australia.

McBeth, M. K., and Shanahan, E. A. (2004). Public opinion for sale: the role of policy marketers in greater yellowstone policy conflict. Policy Sci. 37, 319–38. doi: 10.1007/s11077-005-8876-4

McBeth, M. K., Shanahan, E. A., Anderson, M. C., and Rose, B. (2012). Policy story or gory story: narrative policy framework analysis of buffalo field campaign's YOUTUBE videos. Policy Internet 4, 159–83. doi: 10.1002/poi3.15

McBeth, M. K., Shanahan, E. A., Hathaway, P. L., Tigert, L. E., and Sampson, L. (2010). Buffalo tales: interest group policy stories in greater yellowstone. Policy Sci. 43, 391–409. doi: 10.1007/s11077-010-9114-2

Olson, M. (1965). The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2000). Collective action and the evolution of social norms. J. Econ. Perspect. 14, 137–58. doi: 10.1257/jep.14.3.137

Pidgeon, N. (1998). Risk assessment, risk values and the social science programme: why we do need risk perception research. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 59, 5–15. doi: 10.1016/S0951-8320(97)00114-2

Raco, M., and Imrie, R. (2000). Governmentality and rights and responsibilities in urban policy. Environ. Plan. A 32, 2187–2204. doi: 10.1068/a3365

Renn, O., and Levine, D. (1991). “Credibility and trust in risk communication,” in Communicating Risks to the Public: Technology, Risk, and Society, eds. R. E. Kasperson and P. J. M. Stallen (Springer: Dordrecht), 175–218.

Rose, N. (2006). “Governing advanced liberal democracies,” in The Anthropology of the State, eds. S. Aradhana and A. Gupta (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing), 144–162.