Abstract

Introduction

Although disparities in COVID-19 mortality have been documented at the national and state levels, no previous study has quantified such disparities at the county level by explicitly measuring race-specific COVID-19 death rates. In this paper, we quantify the racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality between the non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White populations at the county level by estimating age-adjusted, race-specific death rates.

Methods

Using COVID-19 case data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, we calculated crude and indirect age-adjusted COVID-19 mortality rates for the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black populations in each of 353 counties for the period February 2, 2020, through January 30, 2021. Using linear regression analysis, we examined the relationship between several county-level measures of structural racism and the observed differences in racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality across counties.

Results

Ninety-three percent of the counties in our study experienced higher death rates among the Black compared to the White population, with an average ratio of Black to White death rates of 1.9 and a 17.5-fold difference between the disparity in the lowest and highest counties. Three traditional measures of structural racism were significantly related to the magnitude of the Black-White racial disparity in COVID-19 mortality rates across counties.

Conclusions

There are large disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates between the Black and White populations at the county level, there are profound differences in the level of these disparities, and those differences are directly related to the level of structural racism in a given county.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than one full year into the COVID-19 pandemic, we are still seeing marked racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates across the USA [1]. Although these disparities have been well documented at the national [2] and state [3] levels, there is a great need to better characterize these disparities at more localized levels of geography, such as at the county level. Many studies have demonstrated a relationship between the percentage of Black or Latinx people living in a county and that county’s overall COVID-19 mortality rate; however, none of these studies explicitly measured race-specific COVID-19 death rates, so they could not quantify the disparity. In this paper, we aim to quantify the racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality between the non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White populations at the county level throughout the USA by explicitly measuring race-specific death rates. In addition, we explore the potential role of structural racism as an explanation for these disparities, focusing on the manifestations of structural racism in the areas of racial segregation, racial economic segregation, disparities in mass incarceration, disparities in accumulated wealth, and disparities in economic mobility from one generation to the next.

The overwhelming majority of studies that have explored racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality at the county level have done so by examining the relationship between the percentage of Black or Latinx residents in a county and that county’s overall COVID-19 death rate [4–22]. However, finding such a relationship does not necessarily demonstrate that a racial disparity exists. It is possible that the percentage of Black residents is an indicator of other factors, such as the overall socioeconomic status of the county, that may lead to both Black and White residents experiencing higher levels of COVID-19-related death. As Cheng et al. explain: “It is possible that Whites also have higher COVID-19 mortality rates in counties with larger shares of Blacks and Hispanics if the conditions in these counties increase the risk of underlying health conditions that increase the risk of transmission and death (e.g., insufficient testing, poor health care access, and social determinants” [12 , p. 607].

Most of the surveillance for racial disparity in COVID-19 outcomes at the county level has also relied on comparing total infection or death rates across counties with differing proportions of racial groups. For example, the COVID-19 Racial Data Tracker [23], perhaps the most widely used tool to understand racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality, tracks counties with the highest overall COVID-19 infection and death rates with respect to the largest racial/ethnic group in each county. While this is extremely useful as a tool, it is limited because it does not present race-specific rates, making it impossible to quantify and compare the magnitude of racial disparities across counties. Ideally, one would directly measure racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality at the county level by explicitly calculating and comparing race-specific death rates. This has not been done previously because of limited available data on the race/ethnicity of COVID-19 decedents at the county level.

Fortunately, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recently released COVID-19 death counts at the county level by race/ethnicity for the most populous counties in the USA. This paper extends the previous research by using these new data to calculate race-specific COVID-19 death rates for the non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White populations and by quantifying these disparities through the calculation of the ratio of these race-specific death rates.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has explicitly identified and quantified racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality at the county level by comparing race-specific death rates. One previous paper that investigated the relationship between green space and racial disparities in COVID-19 infection at the county level calculated race-specific infection rates among Black and White populations in 135 US counties [24]. However, this study did not account for differences in the age distribution of the Black and White populations by deriving age-adjusted infection rates. We have previously shown that relying on crude rates substantially underestimates the magnitude of the Black-White disparity in COVID-19 [25]. This study was also limited because it used green space as the only measure of structural racism [24].

In this paper, we quantify the Black-White racial disparity in COVID-19 mortality rates in 353 US counties by calculating race-specific death rates. We use indirect age adjustment to account for differences in the age distribution of the non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White populations. We then explore the relationship between five different measures of structural racism and the magnitude of the observed racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates across counties. This research advances the existing literature by (1) quantifying racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality at the county level; (2) presenting age-adjusted estimates of race-specific, COVID-19 death rates at the county level; and (3) exploring the potential role of a variety of measures of structural racism in explaining differences in the magnitude of the observed racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality across counties.

Methods

Design Overview

We collected data on 353 counties for which data were available on both the number of COVID-19 deaths reported by race/ethnicity and 2019 population counts by age group and race/ethnicity. Using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), we calculated both crude and indirectly age-adjusted COVID-19 mortality rates for the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black populations in each of the 353 counties based on age group-specific, race/ethnicity-specific population data from the 2019 American Community Survey. For descriptive purposes, we defined the Black-White disparity in COVID-19 mortality as the ratio of the death rate among the Black population to the death rate among the White population. For analytic purposes, the racial disparity was treated by modeling the Black death rate while controlling for the White death rate. In both cases, we generated and compared results using both crude and age-adjusted death rates. There were three parts to our analysis. First, we examined the estimated racial disparities across counties and compared the magnitude of the racial disparities that resulted from crude and age-adjusted mortality estimates. Second, using linear regression analysis, we examined the relationship between several county-level measures of structural racism and the observed differences in racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality across counties. Finally, we explored whether any observed relationship between structural racism and racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality could be explained by the following: disparities in exposure based on occupation; disparities in exposure based on the use of public transportation; disparities in exposure based on household size; disparities in the severity of disease based on the prevalence of comorbidities; and disparities in health care access based on differences in health insurance coverage.

Measures and Data Sources

COVID-19 Mortality Data

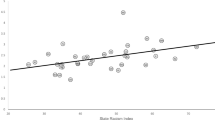

We obtained data on confirmed COVID-19 deaths by race/ethnicity and county from the National Center for Health Statistics’ COVID-19 Death Data and Resources [26]. We used the county-level data set entitled “Provisional COVID-19 Deaths by Race and Hispanic Origin” [27]. Updated weekly, this data set contains county- and race/ethnicity-specific counts of COVID-19 deaths from the NCHS’ National Vital Statistics System. The NCHS prepares the data set by processing, coding, and tabulating data from death certificate information reported directly to it by state health departments. At the time we downloaded the data sets, they included a cumulative count of confirmed COVID-19 deaths from February 2, 2020, through January 30, 2021. There were missing data for deaths in some age strata because the CDC suppresses any cell counts less than 10. There was a total of 353 counties with complete data (see Figure 1 to see the location of these counties).

Calculation of Crude Mortality Rates

We calculated crude COVID-19 death rates for the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black population in each county by dividing the total number of deaths among that racial group by the population of the racial group.

Calculation of Age-Adjusted Mortality Rates

We calculated age-adjusted death rates using indirect age standardization, a standard procedure to generate rates that account for the age distribution of the population, explained in detail by Naing [28] and demonstrated by Preston et al. [29]. Indirect age standardization is especially useful when observed deaths by age strata in the populations of interest are not available. As a useful alternative, age-specific death rates from a reference population are applied to the populations of interest to estimate the expected number of deaths [28, 29]. The ratio of observed to expected deaths in each population unit https://97-percent.org/ is then multiplied by the crude rate in the reference population to generate the indirectly age-adjusted mortality rate for the population of interest.

Death rates were indirectly age adjusted using the entire US population as the standard population. Death rates were standardized using seven age groups: 0–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84, and 85+. We chose these age categories to optimize the balance between having so many strata that we had missing data requiring us to omit counties and having enough age strata to generate stable age-adjusted estimates.

We first calculated national age-specific COVID-19 mortality rates for each age group for the USA as a whole. These would be the expected age-specific death rates for each racial group in each county if there were no mortality differences between racial groups or between counties. We then applied these age-specific national COVID-19 death rates to the race-specific county-level population information, multiplying the age-specific national COVID-19 death rates by the number of people in the age groups in each racial group at the county level to get the expected number of deaths for each racial group. This represents the number of deaths that would be expected among either the non-Hispanic Black or non-Hispanic White population in each county if the actual age-specific mortality rates in that county for both racial groups were identical to the national age-specific mortality rates. Next, we calculated the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) for each racial group in each county by dividing the observed number of deaths by the expected number. From there, we calculated the country-level race-specific COVID-19 age-adjusted death rate as the product of the SMR for the county (race-specific) and the national crude death rate. Essentially, what this procedure is doing is estimating the degree to which the observed number of deaths in a county differs from that expected based on national age-specific mortality data as an estimate of the degree to which that county’s race-specific mortality rate differs from the overall national rate. By multiplying the SMR by the overall national rate, one obtains a race- and county-specific death rate that accounts for differences in the age distribution of each subpopulation. As a result, we were able to generate age-adjusted COVID-19 death rates for both the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black populations in all 353 counties.

The racial disparity in COVID-19 mortality rates was then generated by dividing the Black age-adjusted death rate by the White age-adjusted death rate. We also generated estimates of the racial disparity based on crude death rates for comparison purposes by dividing the Black crude death rate by the White crude death rate.

A complete example of the calculating of race-specific, indirectly age-adjusted COVID-19 mortality rates for the case of Cook County, Illinois, is displayed in Appendix Table 6.

Analysis of Relationship Between Racial Disparities and Structural Racism

Outcome Variable

The main outcome variable was the natural logarithm of the age-adjusted COVID-19 death rate among the non-Hispanic Black population in each county. We modeled the log of the Black mortality rate because the distribution of the death rates was skewed, but a log transformation produced a histogram that approximated the normal distribution. To explore the potential relationship of the structural racism measures to racial disparities in COVID-19, we conducted a linear regression in which we estimated the influence of the structural racism measure of interest on the Black COVID-19 mortality rate, while controlling for the White COVID-19 mortality rate. Given a certain rate of COVID-19 death among the White population in a county, this regression estimates the impact of other independent variables in the model on the magnitude of the Black COVID-19 death rate. Thus, an independent variable with a positive and significant coefficient in the model is associated with a higher racial disparity in mortality rates, since it increases the Black death rate at a fixed level of the White death rate.

Main Predictor Variables

The main predictor variables were five measures of county-level structural racism, each of which has been used in previous studies. First, we used three of the individual indices that comprise the state racism index which we developed and validated in previous research exploring the relationship between structural racism and racial disparities in fatal police shootings [30]. These measures address three critical dimensions of structural racism: residential segregation, mass incarceration, and accumulation of wealth, which is largely determined by historical, racist housing policies [31]. The measures were (1) residential racial segregation, operationalized in several ways described below; (2) Black-White disparities in incarceration rates, operationalized as the ratio of the proportion of incarcerated Black people to the proportion of incarcerated White people; and (3) Black-White disparities in accumulated wealth, defined as the ratio of the proportion of the Black population living in rental housing to the proportion of the White population living in rental housing. In their study of structural racism and COVID-19 mortality at the county level, Tan et al. [18] used similar measures. For each of these measures, higher values indicate a greater degree of structural racism. We derived these measures using data from the 2019 American Community Survey 5-year estimates (for rental housing disparities), 2010 incarceration data from the Prison Policy Initiative [32], and the 2010 Decennial Census and 2019 American Community Survey (for the measures of racial residential segregation).

Second, we used the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE), a measure developed by Douglas Massey [33] and extended by Krieger et al. to measure racialized economic segregation [34, 35]. This measure jointly assesses racial segregation and economic deprivation by analyzing the spatial distribution of the concentration of people at the extremes of race-based economic privilege or economic deprivation [34, 35]. These extremes result from historically inequitable race relations that constitute a central aspect of structural racism. We calculated the ICE as the number of White people in a county with high income minus the number of Black people in a county with low income divided by the total county population, where high and low incomes were defined as the 80th and 20th percentiles for US household income. The scale goes from − 1 to 1, with − 1 indicating a county consisting only of low-income Black people and 1 indicating a county consisting only of high-income White people. Thus, the ICE increases with a high degree of White economic advantage and decreases with a high degree of Black economic disadvantage. We calculated the ICE for racialized economic segregation using data from the 2019 American Community Survey, 5-year estimates.

Third, we used the racial opportunity gap developed by O’Brien et al. in their recent article on structural racism and health disparities at the county level [24]. They introduced the racial opportunity gap “as a novel place-based measure of structural racism” [24 , p. 2]. This measure assesses the racial gap in economic mobility over time. The racial opportunity gap is defined as the difference between the expected income percentiles of Black compared to White children born in families with identical income levels in the same county. Data on the expected economic mobility by race across counties were made publicly available by Chetty et al., who used Internal Revenue Service earnings records to compare the income of young adults to that of their parents decades earlier [36]. These data were kindly provided to us by O’Brien. Higher values of the racial opportunity gap indicate higher levels of structural racism.

Measures of Racial Segregation

We used the index of dissimilarity, calculated at the block level, as the primary indicator of racial residential segregation because it is “the most commonly used and accepted method of measuring segregation” [37] and thus provides a useful, easily understood point of reference. Nevertheless, it has been noted that the use of the index of dissimilarity as a measure of residential racial segregation may be problematic because this measure can be biased, especially under conditions of low systemic segregation and low population units [38]. In addition, calculating the index of dissimilarity at the block level, as we did in our state racism index, cannot be done using recent data, since block-level population figures are only measured every 10 years in the decennial Census and the last such census for which data are available occurred in 2010. To address these potential limitations, we took two additional steps. First, as an alternative measure of racial segregation, we used the index of dissimilarity calculated at the Census tract level (i.e., the Census tract was the lower geographic unit instead of the Census block). This has the added advantage of allowing more recent data to be used because the Census tract population is assessed every year in the American Community Survey. We thus included the index of dissimilarity calculated at the Census tract level using the 2019 American Community Survey 5-year estimates.

Second, we assessed an additional measure of racial residential segregation proposed by Reardon and O’Sullivan [39] that was used by Tan et al. [18] in their analysis of county-level COVID-19 rates: the Spatial Theory Information Index [18]. This is a measure of spatial clustering of Black people and White people in a county [18]. Thus, we used a total of three different measures of racial residential segregation.

Details of each structural racism measure are shown in Appendix Table 7.

Potential Mediating Variables

A secondary aim of our analysis was to investigate whether or not racial disparities in several factors directly related to COVID-19 risk completely explained any observed association between structural racism and racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality. Therefore, we collected data on racial disparities in the following factors.

Differential Exposure Due to Occupation

We used race- and county-specific occupational data from the 2019 American Community Survey [40] to calculate the proportion of workers for each racial/ethnic group in “essential” jobs. The categories included were protective service occupations, food preparation and serving, cleaning and maintenance, personal care and services, construction, repair, production, and transportation and material moving. We operationalized the racial disparity as the ratio of the proportion of Black workers in essential occupations to the proportion of White workers in those occupations.

Differential Exposure Due to Use of Public Transportation

We used race- and county-specific data from the 2019 American Community Survey [41] to calculate the proportion of people in each racial/ethnic group who use public transportation to get to work. The disparity was defined as the proportion of Black people who rely on public transportation to the proportion of White people who rely on public transportation in each county.

Differential Exposure Due to Household Size

We used race- and county-specific data from the 2010 Decennial Census to calculate the average household size for each racial/ethnic group. The disparity was defined as the difference between the average household size for the Black population to the average household size for the White population in each county.

Differential Severity of Disease Due to Comorbidities

Using county estimates of race-specific mortality from CDC WONDER’s multiple cause of death database [42], we derived the ratio of Black to White death rates for each county for the following conditions: obesity, diabetes, circulatory system disorders, and respiratory system disorders.

Differences in Health Care Access Due to Insurance Coverage Disparities

Using the 2019 American Community Survey, 5-year estimates [43], we calculated the ratio of the proportion of Black people in each county without health insurance to the proportion of White people in that county without health insurance.

Details regarding these potential mediating variables are shown in Appendix Table 8.

Control Variables

In each regression, we controlled for the total county population and the percentage of Black residents.

Data Analysis

We first examined the relationship between each of the measures of county-level structural racism and the degree of the racial disparity in COVID-19 mortality in each county. Then, we modeled the relationship between those structural racism measures that were associated with the racial disparity in COVID-19 death rates in the presence of each of the potential mediating variables to determine whether the regression coefficient for the structural racism measures remained significant in the presence of these variables. Because there was multicollinearity between many of these predictor variables (see Appendix Table 9 for a correlation matrix), we examined variance inflation factors for these multiple linear regressions and did not draw any inferences from analyses unless all variance inflation factors were below four, a level typically used to detect multicollinearity.

To ease interpretation of the regression coefficients, we standardized the independent variables so that they had a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Thus, the regression coefficients, once exponentiated, represent the percentage change in the Black COVID-19 death rate for each one standard deviation increase in the predictor variable.

The relationship between structural racism and age-adjusted differentials in COVID-19 mortality is of greatest interest because structural racism itself affects the underlying age distribution of the population; thus, examining crude death rates only may directly mask one of the impacts of structural racism. Nevertheless, because many other papers have employed crude death rates, we also present the relationship between our structural racism measures and the crude death rates for comparison purposes.

Adequacy of County Sample

The 353 counties included in the analysis accounted for 63.7% of the US population and 84.4% of the US Black population (Appendix Table 10). These counties accounted for 95.4% of US COVID-19 deaths and 96.9% of US COVID-19 deaths among Black people (Appendix Table 10). Thus, the sample includes the overwhelming majority of COVID-19 deaths in the nation and provides an adequate representation of counties in which COVID-19 cases occurred in order to draw conclusions regarding racial disparities in COVID-19 death rates and the relationship between these disparities and measures of structural racism. The average population of the 353 included counties is approximately 600,000, while that of the excluded counties is only about 40,000 (Appendix Table 10). The average Black population of the included counties is approximately 100,000, while that of the excluded counties is only about 2000. The results of our analyses should not be generalized to these much smaller and less racially representative counties.

Results

Descriptive Results

Across the 353 counties, the ratio of the age-adjusted Black COVID-19 death rate to the age-adjusted White COVID-19 death rate ranged from a low of 0.4 in Roanoke City, Virginia, to a high of 7.0 in Orange County, North Carolina, with an average of 1.9 (Table 1, Table 2, Appendix Table 11, Fig. 1). Of the 353 counties, 329 (93%) had death rate ratios greater than one, indicating a Black-White disparity in COVID-19 mortality.

In 347 (98.3%) of the 353 counties, the age-adjusted death rate ratio was greater than the crude death rate ratio. Relying on the crude death rate ratio would have identified only 145 counties (41%) with a Black-White disparity in mortality, while relying on the age-adjusted death rate ratio identifies 329 (93%) with such a disparity.

Similar to many previous papers, we found a significant positive relationship between the percentage of Black residents in a county and that county’s overall age-adjusted COVID-19 death rate, with each one standard deviation increase in the percentage Black population associated with a 10.9% increase in the overall COVID-19 death rate (Appendix Table 12). However, as we had hypothesized, a higher percentage of Black residents was associated with both higher White and Black death rates: for each one standard deviation increase in the percent Black population, the Black death rate increased by 2.0% and the White death rate increased by 9.1% (Appendix Table 12).

Overall, the percentage of Black residents in a county was negatively related to the magnitude of the Black-White disparity: each one standard deviation increase in the percentage of Black residents in a county was associated with a 6.5% decrease in the Black-White adjusted death rate ratio (Appendix Table 12). This relationship is also demonstrated by examining the counties with the greatest and lowest racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates: the 10 counties with the greatest disparities had an average of 9.9% Black residents, while the 10 counties with the lowest disparities had an average of 20.8% Black residents (Appendix Table 13).

Analytic Results

Of the five structural racism measures tested, four were significantly and positively related to the magnitude of the age-adjusted racial disparity in COVID-19 mortality across counties: the incarceration ratio, the rental housing ratio, the Index of Concentration at the Extremes for racialized economic segregation, and the racial opportunity gap (Table 3). The magnitude of this relationship was greatest for the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. For each one standard deviation increase in the Index of Concentration at the Extremes for racialized economic segregation, the Black adjusted death rate increased by 11.1% (95% CI, 4.8 to 17.8%). There was no significant relationship between the index of dissimilarity or the spatial clustering score and differences across counties in the magnitude of the racial disparity in COVID-19 mortality.

When we repeated the analysis using crude instead of age-adjusted death rates, the incarceration ratio, Index of Concentration at the Extremes, and racial opportunity gap were still strongly and positively related to the Black COVID-19 death rate, although the rental housing ratio was not (Table 4). Again, the Index of Concentration at the Extremes was related most strongly, with each one standard deviation increase in this index being associated with a 13.3% increase in the crude Black COVID-19 death rate (95% CI, 5.7 to 15.1%). The index of dissimilarity calculated at the block level was now strongly associated with higher Black COVID-19 death rates, with each one standard deviation increase in this index being associated with an 8.7% increase in the crude Black death rate (95% CI, 3.8 to 13.8%).

When we repeated the age-adjusted models while controlling for Black-White differences in risk factors for COVID-19 mortality, the relationships between each of the four structural racism measures that were positively associated with the magnitude of the racial disparity across counties were all still present, and each of them actually increased slightly (Table 5). For example, after adjusting for Black-White differences in the percentage of essential workers, percent taking public transportation to work, average household size, comorbidity death rates, and percent without health insurance, for each one standard deviation increase in the Index of Concentration at the Extremes for racialized economic segregation, the age-adjusted Black COVID-19 death rate increased by 13.7% (95% CI, 6.0 to 22.1%).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly identify and quantify Black-White racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality at the county level by comparing age-adjusted, race-specific death rates. We found that there is, in fact, a substantial disparity in COVID-19 mortality rates at the county level between the non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White populations. Of the 353 counties in our study, 93% experienced higher death rates among the Black compared to the White population. The average Black-White racial disparity was 1.9, but there was a 17.5-fold difference between the counties with the lowest and highest disparities in race-specific COVID-19 mortality. Second, we found that using crude race-specific death rates resulted in a substantial underestimation of the true racial disparity in COVID-19 mortality; in fact, only 41% of counties were found to have racial disparities prior to age adjustment (as opposed to 93% after age adjustment). Third, we found that three traditional measures of structural racism—the incarceration ratio, the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (racialized economic segregation), and the racial opportunity gap—were significantly related to the magnitude of the Black-White racial disparity in COVID-19 mortality rates across counties.

In an attempt to characterize racial disparities in COVID-19 cases or deaths in counties, numerous previous studies have reported that the proportion of Black residents in a county is positively associated with the overall COVID-19 death rate in that county [4–22]. Our concern was that the proportion of Black residents may be correlated with factors that increase not only the Black COVID-19 death rate, but the White COVID-19 death rate as well. In her recently released 2021 work “The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together,” attorney Heather McGhee has documented that many counties with large Black populations, in an effort to avoid having to provide equal resources on the basis of race, have instead chosen to reduce overall expenditures on factors that affect general social conditions in the county [31]. This is one mechanism that could explain why not only Black, but White COVID-19 rates could be higher in counties with larger Black populations. In fact, in this paper, we found that the proportion of Black residents in a county is related to higher levels of COVID-19 mortality among both the Black and White populations. This is why our methods—which directly compare race-specific death rates—improve upon these existing studies. While these previous studies revealed an important correlation between Black population composition and overall COVID-19 mortality rates, they were unable to directly demonstrate the presence of racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality because they did not analyze race-specific mortality data. Here, we are able to directly measure the extent of the racial disparity in each county based on such data.

A second way in which this paper advances the literature is by demonstrating the critical importance of accounting for the age distribution of the population in assessing racial disparities in COVID-19 death. Failure to age adjust the race-specific death rates underestimates the true racial disparities because COVID-19 mortality is greatly influenced by age with older populations being more affected. It is important to take this into consideration because the average life expectancy of the Black population is lower than that of the White population, meaning that they have a younger age distribution, which should theoretically result in a smaller percentage of the Black population being at increased risk of COVID-19 mortality compared to the older White population, thus masking disparities in age-specific mortality rates [44].

We examined the possible role of five standard measures of structural racism at the county level in an effort to explain the observed differences in the magnitude of racial disparity in COVID-19 death rates across counties. We found that three of these measures—the racial opportunity gap, the Index of Concentration at the Extremes for racialized economic segregation, and the incarceration rate ratio—were significantly and robustly positively related to the magnitude of the Black-White disparity in COVID-19 death rates across counties. These relationships held whether we used crude or age-adjusted death rates and persisted even after we controlled for five potential mediating variables that could directly explain racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality. This robust finding may suggest that there are deep aspects of structural racism, going beyond its easily observable and measurable tangible consequences that must be addressed in order to ameliorate the observed racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality.

Our analyses provided mixed results regarding the relationship between residential segregation and Black-White disparities in COVID-19 mortality. For example, the index of dissimilarity was not associated with disparities in age-adjusted death rates but was positively related with disparities in crude death rates. The index of dissimilarity calculated at the Census tract level was not related to disparities in either analysis, nor was the spatial clustering measure. Many previous studies have shown residential segregation to be associated with racial disparities in a variety of health outcomes [45]. Perhaps one explanation for the nuanced results in this study is that although racial segregation was associated with higher Black COVID-19 death rates, it was even more strongly associated with White COVID-19 death rates. This in some cases actually led to a negative, although not statistically significant, relationship between residential segregation and racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality. We hypothesize that residential segregation may not have been associated with lower COVID-19 death rates among the White population because as an infectious disease, higher rates in one part of a county are likely to translate into higher rates in other parts of that same county. Torrats-Espinosa similarly hypothesized that higher levels of segregation could translate into higher rates of White COVID-19 deaths “if minorities and Whites overlap in public places (e.g., public transit and restaurants) so that the virus spills over from the minority clusters to the rest of the population through these encounters” [46 , p. 2]. Although residential segregation is discriminatory, infectious diseases are not, indicating that structural racism may harm the entirety of the communities that it affects, and not just the specific minority communities that are being oppressed. This finding is enlightening in view of McGhee’s argument that structural racism is not a zero-sum game and that ending structural racism may benefit both the White and Black populations [31].

The results of this investigation have several implications for future research, data collection, and public health policy. Specifically, they have implications for each of the four dimensions that Bailey et al. articulated as being essential to dismantle structural racism and its consequences in their sentinel article in the New England Journal of Medicine: (1) better documenting racial health disparities; (2) improving the collection of race/ethnicity-specific health data; (3) shining the light on the medical and public health systems themselves and their potential role in enabling structural racism; and (4) creating systemic and structural change to dismantle structural racism at its roots [47]. First, we provide the strongest evidence to date that there is indeed a profound racial disparity in COVID-19 mortality at the county level and that the magnitude of this disparity across counties is equally profound. Second, this investigation demonstrates the importance of collecting race/ethnicity-specific data. The previous studies examining COVID-19 mortality at the county level were unable to quantify racial disparities because of the lack of race-specific mortality data. We were only able to conduct this analysis because the CDC eventually began releasing data on the race and ethnicity of COVID-19 victims in all of the most populous counties in the country. Third, these findings should force us to reflect on the public health profession itself and its failure to have anticipated and prevented the racial disparities that resulted during the pandemic. Fourth, our findings point to the need for systemic, structural, and institutional policy changes that improve the health of underserved populations.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this analysis is that many counties failed to track COVID-19 deaths by race/ethnicity or used varying definitions that were inconsistent. In addition, the CDC does not report counts for any cell in which there are fewer than 20 deaths, nor does it report rates that are based on fewer than 20 deaths. As a result of these two limitations, our analysis was constrained to 353 counties. Nevertheless, these 353 counties account for 63.7% of the US population and 81.7% of the US Black population. Moreover, they account for 95.4% of US COVID-19 deaths during the study period. The results of this analysis should not be generalized to counties that have very low Black populations.

Because of the absence of age-specific and race-specific data for many counties, we relied upon indirect rather than direct age standardization. While it may not be as precise as direct age standardization, it still accounts for differing age distributions among various counties and between racial groups.

Third, there was collinearity between several of the predictor variables, limiting our ability to estimate independent effects of each predictor. We have identified several four measures of structural racism that correlate with higher racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality at the county level; however, the independent effects of these measures should be examined in future studies.

Fourth, the index of dissimilarity calculated at the block level was based on 2010 data because no more recent data were available at that level. We addressed this by also including the index of dissimilarity calculated at the Census tract level, for which 2019 data were available. Additionally, average household size by race was also available only as recently as the 2010 decennial Census. While inaccuracy in this variable would not affect our estimation of racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality or their relationship with structural racism measures, it could affect our conclusion that there is no change in the regression coefficients for the structural racism measures after controlling for the potential mediating effects of differences in household size. This particular analysis should be replicated once the data from the 2020 Decennial Census are available.

Finally, this analysis only examined racial disparities between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White populations. There is strong evidence of COVID-19-related racial disparities among other racial/ethnic groups, including Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian-American groups, to name a few, and each of these needs to be studied in its own right.

Conclusion

In spite of these limitations, this paper has demonstrated that there are large and previously underestimated disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates between the non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White populations at the county level, that there are profound differences in the level of these disparities, and that those differences are directly related to the level of structural racism in a given county. Three measures of structural racism at the county level were significantly associated with the magnitude of the racial disparity in COVID-19 mortality: the Index of Concentration at the Extremes for racialized economic segregation, the racial opportunity index, and the incarceration ratio. These results suggest that in order to reduce racial disparities in this or future pandemics, it will be necessary to dismantle structural racism and its consequences, particularly the mass incarceration of Black people, the massive racial disparity in wealth and access to resources, and the profound disparities in upward mobility. Finally, our findings demonstrate that dismantling structural racism is not a zero-sum game, but will yield benefits for the entire population, especially in the context of infectious diseases and health outcomes.

Data Availability

The database produced in this research project is available from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

American Community Survey

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- COVID-19:

-

coronavirus disease 2019

- ICE:

-

Index of Concentration at the Extremes

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- SMR:

-

standardized mortality ratio

- SRR:

-

standardized rate ratio

References

Lee FC, Adams L, Graves SJ, Massetti GM, Calanan RM, Penman-Aguilar A, et al. Counties with high COVID-19 incidence and relatively large racial and ethnic minority populations—United States, April 1-December 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(13):483–9.

Bassett MT, Chen JT, Krieger N. Variation in racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality by age in the United States: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(10):e1003402. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003402. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Gross CP, Essien UR, Pasha S, Gross JR, Wang S, Nunez-Smith M. Racial and ethnic disparities in population-level Covid-19 mortality. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3097–9.

Gaglioti AH, Li C, Douglas MD, Baltrus PT, Blount MA, Zahidi R, et al. Population-level disparities in COVID-19: measuring the independent association of the proportion of Black population on COVID-19 cases and deaths in US counties. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021;27(3):268–77.

Figueroa JF, Wadhera RK, Mehtsun WT, Riley K, Phelan J, Jha AK. Association of race, ethnicity, and community-level factors with COVID-19 cases and deaths across U.S. counties. Healthcare. 2021;(9):100495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2020.100495. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Cyrus E, Clarke R, Hadley D, Bursac Z, Trepka MJ, Devieux JG, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on African American communities in the United States. medRxiv. Preprint. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.15.20096552. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Khanijahani A. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths in the United States: a county-level analysis as of November 2020. Ethn Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2020.1853067. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Mahajan UV, Larkins-Pettigrew M. Racial demographics and COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths: a correlational analysis of 2886 US counties. J Public Health. 2020;42(3):445–7.

Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, Baral S, Mercer L, Beyrer C, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;47:37–44.

Hamman MK. Disparities in COVID-19 mortality by county racial composition and the role of spring social distancing measures. Econ Hum Biol. 2021;41:100953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2020.1009053. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Strully K, Yang T-C, Liu H. Regional variation in COVID-19 disparities: connections with immigrant and Latinx communities in U.S. counties. Ann Epidemiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.08.016. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Cheng KJG, Sun Y, Monnat SM. COVID-19 death rates are higher in rural counties with larger shares of Blacks and Hispanics. J Rural Health. 2020;36:602–8.

Feinhandler I, Cilento B, Beauvais B, Harrop J, Fulton L. Predictors of death rate during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare. 2020;8(3):339. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030339. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Richmond HL, Tome J, Rochani H, Fung IC, Shah GH, Schwind JS. The use of penalized regression analysis to identify county-level demographic and socioeconomic variables predictive of increased COVID-19 cumulative case rates in the state of Georgia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8036. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218036. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Liao TF, De Maio F. Association of social and economic inequality with coronavirus disease 2019 incidence and mortality across US counties. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034578. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaanetworkopen.2020.34578. Accessed 27 Jan 2021.

Karmakar M, Lantz PM, Tipirneni R. Association of social and demographic factors with COVID-19 incidence and death rates in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2036462. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36462. Accessed 30 Jan 2021.

Anaele BI, Doran C, McIntire R. Visualizing COVID-19 mortality rates and African-American populations in the USA and Pennsylvania. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00897-2. Accessed 11 Feb 2021.

Tan SB, de Souza P, Raifman M. Structural racism and COVID-19 in the USA: a county-level empirical analysis. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00948-8. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Khanijahani A, Tomassoni L. Socioeconomic and racial segregation and COVID-19: concentrated disadvantage and Black concentration in association with COVID-19 deaths in the USA. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-0965-1. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Cunningham GB, Wigfall LT. Race, explicit racial attitudes, implicit racial attitudes, and COVID-19 cases and deaths: an analysis of counties in the United States. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242044. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242044. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Li D, Gaynor SM, Quick C, Chen JT, Stephenson BJK, Coull BA, et al. Unraveling US national COVID-19 racial/ethnic disparities using county level data among 328 million Americans. medRxiv. Preprint. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.02.20234989. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

Yang T-C, Choi SE, Sun F. COVID-19 cases in US counties: roles of racial/ethnic density and residential segregation. Ethn Health 2020 https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2020.1830036. Accessed 26 Jan 2021.

COVID Tracking Project and the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research. The COVID Racial Data Tracker. Washington, DC: The COVID Tracking Project; 2021. [Available from: https://covidtracking.com/race]. Accessed 2 Apr 2021.

O’Brien R, Neman T, Seltzer N, Evans L, Venkataramani A. Structural racism, economic opportunity and racial health disparities: evidence from U.S. counties. SSM Popul Health 2020;11:100564 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100564. Accessed 22 Mar 2021.

Siegel M, Critchfield-Jain I, Boykin M, Owens A. Actual racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality for the non-Hispanic Black compared to non-Hispanic White population in 35 US states and their association with structural racism. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01028-1.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Provisional death counts for coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Index of COVID-19 surveillance and ad-hoc data files. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2021; [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/covid-19-mortality-data-files.htm]. Accessed 7 Feb 2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Provisional COVID-19 deaths by race and Hispanic origin (County). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2021; [Available from: https://data.cdc.gov/dataset/Provisional-COVID-19-Death-Counts-by-County-and-Ra/k8wy-p9cg/]. Accessed 7 Feb 2021.

Naing NN. Easy way to learn standardization: direct and indirect methods. Malays J Med Sci. 2000;7(1):10–5.

Preston SH, Heuveline P, Guillot M. Demography: measuring and modeling population processes. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers; 2001.

Mesic A, Franklin L, Cansever A, Potter F, Sharma A, Knopov A, et al. The relationship between structural racism and Black-White disparities in fatal police shootings at the state level. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(2):106–16.

McGhee H. The Sum of Us: What racism costs everyone and how we can prosper together. New York: One World; 2021.

Wagner P, Kopf D. The racial geography of mass incarceration. Northampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative; 2015. [Available from: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/racialgeography/]. Accessed 22 Mar 2021.

Massey DS. The prodigal paradigm returns: ecology comes back to sociology. In: Booth A, Crouter A, editors. Does it take a village? Community effects in children, adolescents, and families. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. p. 41–8.

Krieger N, Feldman JM, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Coull BA, Hemenway D. Local residential segregation matters: stronger association of Census tract compared to conventional city-level measures with fatal and non-fatal assaults (total and firearm related), using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) for racial, economic, and racialized economic segregation, Massachusetts (US), 1995-2010. J Urban Health. 2017;94:244–58.

Krieger N, Waterman PD, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G. Public health monitoring of privilege and deprivation with the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):256–63.

Chetty R, Hendren N, Jones MR, Porter SR. Race and economic opportunity in the United States: an intergenerational perspective. Q J Econ. 2020;135(2):711–83.

Peuquet SW. Using the “Index of Dissimilarity” to measure residential racial segregation. Center for Community Research & Service, University of Delaware [Available from: http://www1.udel.edu/uapp800/Lecture%20Material/Index%20of%20Dissimilarity%20Example.htm]. Accessed 1 Jul 2021.

Allen R, Burgess S, Davidson R, Windmeijer F. More reliable inference for the dissimilarity index of segregation. Econ J. 2014;18(1):40–66.

Reardon SF, O’Sullivan D. Measures of spatial segregation. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34(1):121–62.

American Community Survey. Sex by occupation for the civilian employed population 16 years and over, by race/ethnicity, 2019, 5-year estimates. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; 2021.

American Community Survey. Means of transportation to work, by race/ethnicity, 2019, 5-year estimates. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; 2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause of Death 1999-2019 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2020. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program [Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html]. Accessed 5 Mar 2021.

American Community Survey. Health insurance coverage by age, 2019, 5-year estimates. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; 2021.

Bharmal N, Tseng C-H, Kaplan R, Wong MD. State-level variations in racial disparities in life expectancy. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1 Pt 2):544–55.

Collins CA, Williams DR. Segregation and mortality: the deadly effects of racism? Sociol Forum. 1999;14:495–523.

Torrats-Espinosa G. Using machine learning to estimate the effect of racial segregation on COVID-19 mortality in the United States. PNAS. 2021;118(7):1–7, e2015577118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015577118. Accessed 22 Apr 2021.

Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768–73.

Acknowledgements

Tableau Public was used in the creation of the map shown in Fig. 1. The use of Tableau Public is governed by the terms of service outlined at https://www.tableau.com/tos.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This is a secondary analysis of publicly available data obtained, analyzed, and reported at an aggregated state level. No human subject or identification data is collected or analyzed in this study.

Informed Consent

No human subject was involved in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Table 6. Demonstration example of method for indirect age standardization of race- and county-specific COVID-19 mortality rates and calculation of racial disparity: Cook County, Illinois

Step 1: Calculate age-specific death rates for the entire U.S. population. These would be the expected age-specific death rates for each racial group in each county if there were no mortality differences between racial groups or between counties. Also calculate overall mortality rate for the U.S. population (bottom line).

United States | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Age group | Number of deaths | Population in age group | Age-specific mortality rate (per 100,000) |

0-34 | 3,412 | 148,919,430 | 2.29 |

35-44 | 7,057 | 41,914,845 | 16.84 |

45-54 | 19,454 | 40,863,107 | 47.61 |

55-64 | 49,131 | 42,468,113 | 115.69 |

65-74 | 89,896 | 31,575,561 | 284.70 |

75-84 | 117,104 | 16,140,238 | 725.54 |

85+ | 135,324 | 6,358,229 | 2128.33 |

Entire population | 421,378 | 328,239,523 | 128.38 |

Step 2: Apply national age-specific mortality rates to the number of people in each age group by race in the county of interest to estimate the expected number of deaths if there were no differences compared to national rates.

Cook County, Illinois | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | ||||||

Age group | Population | Expected death rate per 100,000 (from table above) | Expected number of deaths | Age group | Population | Expected death rate per 100,000 (from table above) | Expected number of deaths |

0-34 | 558,253 | 2.29 | 12.78 | 0-34 | 849,414 | 2.29 | 19.45 |

35-44 | 143,210 | 16.84 | 24.12 | 35-44 | 285,032 | 16.84 | 48.00 |

45-54 | 149,739 | 47.61 | 71.29 | 45-54 | 267,794 | 47.61 | 127.50 |

55-64 | 158,563 | 115.69 | 183.44 | 55-64 | 316,732 | 115.69 | 366.43 |

65-74 | 104,142 | 284.70 | 296.49 | 65-74 | 241,444 | 284.70 | 687.39 |

75-84 | 56,387 | 725.54 | 409.11 | 75-84 | 128,896 | 725.54 | 935.19 |

85+ | 19,500 | 2128.33 | 415.02 | 85+ | 64,819 | 2128.33 | 1,379.56 |

Entire population | 1,189,794 | 1,412.25 | Entire population | 2,154,131 | 3,563.52 | ||

Step 3: Calculate standardized mortality ratios (SMR) for each racial group by dividing the observed number of deaths by the expected number of deaths.

Cook County, Illinois | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | ||||

Observed deaths | Expected deaths | SMR | Observed deaths | Expected deaths | SMR |

2,440 | 1,412.25 | 1.728 | 3,467 | 3,563.52 | 0.973 |

Step 4: Estimate age-adjusted, race-specific death rate in each county by multiplying the SMR by the national crude death rate from step 1.

Cook County, Illinois | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | ||||

SMR | National crude death rate | Estimated race-specific death rate | SMR | National crude death rate | Estimated race-specific death rate |

1.728 | 128.38 | 221.84 | 0.973 | 128.38 | 124.91 |

Step 5: The racial disparity in age-adjusted COVID-19 death rates is estimated by dividing the Black age-adjusted death rate by the White age-adjusted death rate.

Racial disparity = 221.84/124.91 = 1.8

Step 6: The racial disparity in death rates based on crude mortality rates can be derived for comparison purposes by dividing the crude Black death rate by the crude White death rate.

Here, the crude Black death rate is 2,440 deaths/1,189,794 = 205.08 per 100,000.

The crude White death rate is 3467 deaths/2,154,131 = 160.95 per 100,000.

Thus, the racial disparity based on the crude mortality rates is 205.08/160.95 = 1.3, which is substantially lower than the racial disparity of 1.8 based on the age-adjusted rates.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siegel, M., Critchfield-Jain, I., Boykin, M. et al. Actual Racial/Ethnic Disparities in COVID-19 Mortality for the Non-Hispanic Black Compared to Non-Hispanic White Population in 353 US Counties and Their Association with Structural Racism. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 9, 1697–1725 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01109-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01109-1