Abstract

Employees’ felt neglect by their employer signals to them that their employer violates ethics of care, and thus, it diminishes employee perceptions of work meaning. Drawing upon work meaning theory, we adopt a relationship-based perspective of felt neglect and its downstream outcome— reduction in organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB) amid the COVID-19 pandemic. We propose and test a core relational mechanism— relatedness need frustration (RNF)—that transmits the effect of felt neglect onto work meaning. A four-wave survey study of 111 working employees in the USA demonstrated that employees’ felt neglect had negative implications for their work meaning and subsequent OCB due to their RNF. Our findings contribute to research on ethics of care and work meaning theory and stress the importance of work meaning amid crises. In addition, our findings suggest steps that employers can take to mitigate employees’ felt neglect (a violation of ethics of care) and its negative ramifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused one of the worst employment problems in the US history.Footnote 1 Many organizations have been on the verge of bankruptcy, struggling to survive in the drastically changed environment. During this trying time, while many employers cannot formally reward their employees, they likely hope that their employees can come together and help the organization to keep abreast with changes in the work conditions by not only doing their jobs, but also going above and beyond the expectations, such as putting extra effort and time in their responsibilities, volunteering for extra tasks, and helping each other and clients/customers. Such behaviors, known as organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB; Organ, 1988), can help organizations be more resilient and more responsive to the crisis and, thus, recover more quickly. While employers’ need for employees’ OCB is understandable, crises are also the times when employees expect employers’ attention and care the most (Harvey & Haines, 2005). However, due to the pressing need to keep their business alive amid a major crisis, employers’ focus is, at least temporarily, often diverted from paying attention to and taking care of their employees, thus violating ethics of care.

Centering on interpersonal relationships, ethics of care states that the job of a leader or a person in a position of authority is to take care of and fulfill responsibility for others, especially amid crises (Ciulla, 2009). Care means showing “emotional concern about the well-being of others” (Ciulla, 2009: 3; also see Chun, 2005; Gilligan, 1982; Noddings, 1984; Tronto, 2006 for similar conceptualizations). Different from ethics of justice, which focuses on judging the morality of behaviors based on one’s adherence to the rules and regulations guided by acceptable principles, ethics of care focuses on judging the morality of behaviors based on one’s attentiveness and responsiveness to the needs of those for whom one is responsible (Gilligan, 1982; Noddings, 1984; Tronto, 2006). Ethics of care emphasizes benevolence as a virtue, and stresses creating and strengthening social bonds (Gilligan, 1982), considering others’ feelings, and relying on the narrative and contextual complexity of social relationships rather than formal logic and impartial judgment for problem solving (Simola, 2003). Moral concerns regarding ethics of care “include the struggle against indifference to people and relationships, as well as the concern that one is not helping when one could be (Gilligan, 1982)” (Simola, 2003: 354). Emerging findings indicate that when leaders engage in ethics of care (such as by expressing care and compassion to their employees) during the COVID-19 pandemic, it helps employees and organizations better cope with this crisis through experiences of positive moral emotions and engagement in voice behaviors (Belkin & Kong, 2021). Similarly, a recent qualitative study conducted by Liu and colleagues (2021) examined how leaders in the US higher education navigated the COVID-19 pandemic and found that enactment of ethics of care was one of the critical elements of successful decision-making in this highly uncertain and stressful crisis.

A lack of expected care and attention, on the other hand, may lead to employees’ feelings of being neglected by their employer, which can have a profound adverse impact on the employees’ experiences and behaviors during crises. That is, when employers are not responsive to their employees’ needs (Gilligan, 1982), it can give rise to employees’ felt neglect. Even though felt neglect has been predominantly examined with respect to caretakers’ neglect of children and elders as a critical detrimental factor for their well-being (Stoltenborgh et al., 2013; Storey, 2020), we believe that employers’ neglect of their employees during a major crisis can also have a detrimental effect on employees’ experiences and behaviors at work. Indeed, felt neglect was a common reason for complaints amid the COVID-19 pandemic by employees in healthcare (Stephenson, 2020). It also seemed to be a pervasive feeling shared by many employees across industries. According to the anonymous comments we gathered from our study participants, felt neglect was mentioned as a common experience amid this pandemic: “I feel neglected and forgotten because my employer has not answered my emails about my work schedule”; “My employer hasn’t given much concrete information to us about when we’re returning to the office, whether there are any layoffs planned, etc.”; “I don’t receive much direct attention from my employer, so I feel somewhat of an afterthought”; and “They don’t really communicate anything to me.” Given the widespread feelings of being neglected among employees, what are possible negative ramifications of felt neglect? An answer to this question can shed light on how employers can better demonstrate ethics of care, while managing the tension between employees’ needs and business needs amid crises.

We adopt the lens of ethics of care and address our research question by focusing on the effect of felt neglect on work meaning and subsequent OCB through relational need frustration during the early (acute) stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, when disruption and uncertainty was at the peak in the USA in 2020. When encountering a novel, unexpected, and stressful event like the COVID-19 pandemic, employees will be prompted to make sense of and adapt to the new environment (Christianson & Barton, 2021; Maitlis & Christianson, 2014; Maitlis & Sonenshein, 2010; Weick, 1995). We draw upon work meaning theory (Rosso et al., 2010) to argue that amid a large global crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic in which employees’ sense of control, order and coherence is threatened or lost, employees look to their employer for care and help, which shapes their work meaning (Waters et al., 2021). We view work meaning as an important enabling factor of employees’ discretionary behaviors such as OCB, and employees’ felt neglect by their employer as a detrimental antecedent of their work meaning. Specifically, we propose that felt neglect frustrates employees’ basic need for relatedness (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 2000), thus reducing their work meaning (Rosso et al., 2010) and hindering their OCB.

By delineating the adverse effect of employees’ felt neglect on their relational experiences, work meaning, and OCB, the present study advances two streams of research. First, we join the emerging research on organizational ethics amid the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Liu et al, 2021; Thomas & Dasgupta, 2020) or more broadly in times of crises (St. John and Pearson, 2016; Thomas and Young, 2011), by focusing on ethics of care. Unlike “normal” times when employer–employee relationships are largely based on social exchange (Shore et al., 2006), these relationships become predominantly need-based amid crises. Thus, employers’ care and concern for employees, which facilitates employees’ sensemaking through the lens of ethics of care, becomes a “moral duty” of employers (Liu et al., 2021). We aim to bring attention of organizational ethics scholars to this important part of moral employers’ responsibilities and highlight the negative ramifications of a violation of ethics of care amid crises.

Second, we contribute to work meaning theory (Rosso et al., 2010) by identifying felt neglect as an important relational hindrance to work meaning in a major crisis. Among employees’ multiple relationships in the workplace, the relationship with their employer has a particularly significant influence on employees’ relational experiences. RNF, as employees’ subjective interpretation of felt neglect, represents a need-based relational mechanism grounded in self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000) and belongingness theory (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). By frustrating the fundamental need for relatedness, felt neglect prompts individuals to make sense of their negative social environment in a way that reduces their work meaning and subsequent behavioral response. Ward and King (2017: 67) noted that “[t]he power of social relationships to create meaning in the workplace implies as well that negative social experiences at work are thus likely to impair meaning.” Our study not only highlights the importance of a need-based relational perspective for explaining the important determinants of work meaning, but also broadens the literature by shifting research attention from enablers of work meaning to hindrances to work meaning. Additionally, work meaning theory has a limited focus on the outcomes of work meaning, though work meaning can predict critical discretionary behaviors and positive attitudes of employees (e.g., Liden et al., 2000; Spreitzer, 1995). By delineating OCB as an outcome of work meaning, we extend Rosso et al.’s (2010) work meaning theory to better explain employees’ outcomes ensuing from felt neglect through the lens of ethics of care.

Theory and Hypotheses

Work Meaning During a Major Crisis

Individuals try to derive meaning from their experience and/or environment through interpretation, and enact actions accordingly in the wake of novel, unexpected, or stressful events (Baumeister & Vohs, 2002; Maitlis & Christianson, 2014). Thus, finding meaning in their work is especially important for employees in uncertain and threatening situations like the COVID-19 pandemic, when the quality of their relationship with their employer becomes a key factor that shapes work meaning (e.g., Robertson et al., 2020). Baumeister and Vohs (2002) argued that individuals’ search for meaning is driven in part by their need for self-worth and values/virtues. As most adults spend nearly half of waking hours on work (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997), work represents a focal domain for individuals’ meaning to gather senses of self-worth, control, and stability in an ambiguous or turbulent environment (Cartwright & Holmes, 2006).

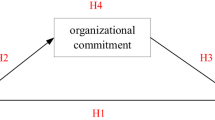

However, meaning is socially constructed and influenced by others’ intentional or unintentional behaviors (Corley & Gioia, 2004; Dutton et al., 2002; Pfeffer, 1981). Employers’ treatment plays an important part in shaping employees’ work meaning, particularly when employees’ existing meaning system is threatened by a major crisis (Maitlis & Lawrence, 2007; Maitlis & Sonenshein, 2010). Since individuals’ work meaning is core to their identity (Rosso et al., 2010), an employer’s failure to provide appropriate meaning related to ethics of care can reduce employees’ work meaning. Consistent with Baumeister and Vohs’ (2002) view, Rosso et al. (2010) proposed work meaning theory, which suggests that one important source of employees’ work meaning is their relational connections at work (i.e., a relationship-based perspective of work meaning). Accordingly, we propose that feeling neglected by their employer will reduced employees’ work meaning and engagement in OCB. In order to unpack the underlying relational mechanism that transmits the effect of felt neglect onto work meaning and OCB, we focus on relatedness need frustration (RNF; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013) as a need-based mechanism (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 2000). Given that employees’ relationship with their employer, typically, is based on social exchange, in our model we also control for psychological contract violation (PCV), defined as employees’ affective reaction to the perceived failure of their employer to fulfill one or more promised obligations, as an alternative, exchange-based mechanism (Morrison & Robinson, 1997). Figure 1 presents our conceptual model.

Felt Neglect by the Employer: Conceptualization

Based on the dictionary definition of neglect, we conceptualize employees’ felt neglect as employee perceptions of being given insufficient care or attention due or expected from their employer who they deem responsible for their welfare. Felt neglect has its moral overtone (Stillman & Baumeister, 2009). When employees feel neglected by their employer, they will likely perceive themselves as a victim of their employer’s un-empathetic treatment due to lack of expected attention and care in times of need. Below we elaborate on the features of felt neglect by distinguishing it from other related constructs.

First, felt neglect differs from a neglect behavior (Hirschman, 1970). Employees’ neglect, as a “lax and disregardful behavior” such as silence (Farell, 1983: 598), is a behavioral response to job dissatisfaction or low-quality relationships. Rusbult et al. (1982) noted that neglect is a distinct response to dissatisfaction in romantic relationships; those who engage in neglect may “ignore their partner, spend less time together, refuse to discuss problems, treat the partner badly emotionally or physically, or criticize the partner for things unrelated to the problem” (Naus et al., 2007: 689). Dissatisfied employees who exhibit neglect may call in sick to avoid dealing with work issues, come in late to avoid work problems, or display less interest and make more mistakes at work (Withey & Cooper, 1989). Turnley and Feldman (1999) demonstrated that employees’ neglect behavior was a function of their social exchange relationship with their employer. On the other hand, Rusbult et al. (1988) found that employees’ high job satisfaction and high investment in their job hindered their neglect behavior. Both Rusbult et al.’s (1988) and Turnley and Feldman’s (1999) findings suggest that employees’ neglect behavior is an outcome of low-quality social exchange relationship with their employer (also see Naus et al., 2007). Thus, even though both felt neglect and a neglect behavior are relationship-based, these two constructs are different, with the former being perceived as deficiency in due care and attention, whereas the latter as a deviant behavior. Additionally, employees’ neglect behavior can be a consequence of their felt neglect.

Second, felt neglect is associated with expectation violation; however, felt neglect may not necessarily be synonymous with psychological contract breach. A psychological contract refers to “individual beliefs, shaped by the organization, regarding terms of an exchange agreement between individuals and their organization” (Rousseau, 1995: 9; also see Rousseau, 2001; Zhao et al., 2007). Different from general expectations, the promissory expectations inherent in a psychological contract “emanate from perceived implicit or explicit promises by the employer” (Robinson, 1996: 575). Accordingly, employees detect psychological contract breach when perceiving their employer’s failure to fulfill its promissory expectations (Robinson & Rousseau, 1994), which may be transactional (short-term exchange of economic inducements and contributions), relational (long-term employment relations with both economic and socioemotional resources being exchanged), or balanced promissory expectations (open-ended relational emphasis with transactional terms of performance-reward contingencies (Hui et al., 2004). McAllister and Bigley (2002: 895) argued that “care cannot be easily equated with any particular configuration of managerial and human resource practices…specific practice sets reflective of organizational care may change over time in response to shifting situational contingencies.” Felt neglect may be temporary or long-term, and the expectations related to attention and care provided by employers may not be promised as employer obligations. However, if employers explicitly promise to give attention and care to employees amid crises, then felt neglect can be a part of employees’ psychological contract breach.

Felt neglect can also be differentiated from transitional arrangements, which refer to “a breakdown or absence of an agreement” between employers and employees, “as observed in unstable circumstances such as radical change or downsizing in which commitments between the parties are eroded or do not exist” (Hui et al., 2004: 312). Felt neglect suggests that employers do not provide due or expected attention or care; however, employers may still fulfill other obligatory promises such as rewards for employees’ contributions (Fig. 1).

Third, felt neglect differs from perceived ignore or ostracism. Ignore refers to “intentionally not listen[ing] or giv[ing] attention to” someone, and ostracism refers to “the action of intentionally not including someone in a social group or activity” (Cambridge English Dictionary). Neglect can be either intentional or unintentional, whereas ignore and ostracism are intentional. Moreover, neglect is associated with insufficient, but not necessarily zero, attention or care, and does not necessarily entail social rejection or exclusion, whereas ignore and ostracism are associated with a complete lack of care or attention, and social rejection or exclusion is a defining element. Robinson et al., (2013: 206–207) noted that workplace ostracism occurs “when an individual or group omits to take actions that engage another organizational member when it is socially appropriate to do so,” and “[t]his definition subsumes social rejection, social exclusion, ignoring, and shunning, as well as other behaviors that involve the omission of appropriate actions that would otherwise engage someone, such as when an individual or group fails to acknowledge, include, select, or invite another individual or group.”

Finally, felt neglect is not the bipolar opposite of perceived organizational support (POS), defined as “the extent to which employees perceive that their contributions are valued by their organization and that the firm cares about their well-being” (Eisenberger et al., 1986: 501). Although both felt neglect and POS are related to “employees’ tendency to assign the organization humanlike characteristics” (Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003: 492–493), felt neglect does not represent employees’ perception of their employer disregarding their contributions. Rather, from the ethics of care perspective, felt neglect represents employees’ perceptions of the deficiency merely in their employer’s provision of attention and care, as their employer is expected to show concern about employees’ welfare and respond to employees’ needs amid crises (Clark et al., 1986). In contrast, POS is largely based on employees’ schema of an exchange relationship with their employer (i.e., their employer is obligated to provide inducements and socioemotional benefits in exchange for employees’ contributions; Clark et al., 1986; Eisenberger et al., 1986). Additionally, as Rhoades and Eisenberger (2002) noted, POS is associated with employer-employee social exchange involving rewards, working conditions, supervisor support, and procedural justice. Yet some of these factors are not necessarily associated with felt neglect.

Relationship-Based Implications of Felt Neglect for Work Meaning and OCB

As many employers struggled to keep their business alive and many employees had work remotely from home, felt neglect by the employer should make a salient input for their sensemaking process during the pandemic, which shapes their work meaning and enactment of work behaviors. According to Pratt and Ashforth (2003), meaning refers to “the output of having made sense of something, or what it signifies; as in an individual interpreting what her work means, or the role her work plays, in the context of her life” (Rosso et al., 2010: 94). Work meaning is “at the core of employees’ experiences of their jobs” (Wrzesniewski et al., 2003: 288). Although work meaning can be negative, we follow the conventional view and focus on positive work meaning, which refers to positive “associations, frames, or elements of work in use by employees that define work as representing a valued, constructive activity” (Wrzesniewski et al., 2013: 288). When employees perceive a high level of work meaning, they find “significant and positive valence” in their work and have a subjective, personal experience of coherence and balance (Steger et al., 2012: 323). Work meaning ultimately is determined by individuals, though it is shaped by their social and organizational contexts (Rosso et al., 2010; Wrzesniewski et al., 2003).

When employees have a negative experience with their employer, their interpretation of work will likely be negative. On the other hand, when perceiving their work as meaningful, employees will likely increase OCB to maintain the quality of their employment relationship (Wayne et al., 1997). Lee and Allen (2002) considered work meaning to be a facet of intrinsic job cognitions, which facilitates employees’ OCB toward their employer. Work meaning is integrated by employees into the beliefs regarding whether their work is significant, worthy, and congruent with their values (Allan et al., 2019). Nonetheless, work meaning is not self-serving, but rather balanced in terms of self- and other-focused goals (Lips-Wiersma & Wright, 2012). Employees who perceive their work to have meaning are willing to be good organizational citizens who exert discretionary efforts and make discretionary contributions in the form of keeping up with work changes, helping others, complying with rules and regulations, and not complaining about small issues (Organ, 1988). When feeling more neglected, employee will perceive lower work meaning and thus engage less in OCB that demonstrate their meaningful contributions or care for their employer. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1

Employees’ felt neglect is negatively related to their work meaning.

Hypothesis 2

Employees’ work meaning mediates the relationship between their felt neglect and OCB.

Relatedness Need Frustration as a Mechanism Between Felt Neglect and Work Meaning

Adopting the lens of ethics of care and drawing upon work meaning theory, we focus on RNF as a core relational mechanism explaining how employees’ felt neglect (as a violation of ethics of care) leads to reduced work meaning. First, employees’ felt neglect conveys employer’s unresponsiveness to their need for attention and care and thus likely frustrates their relatedness need, which is an intrinsic need across cultures (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000). This view is aligned with Lepsito and Pratt’s (2017) argument that work meaning is related to eudaimonia or “the satisfaction of organismic needs, self-realization or actualizing one’s potential” (Heintzelman & King, 2014: 562). Relatedness (Baumeister & Leary, 1995) refers to “individuals’ inherent propensity to feel connected to others; that is, to be a member of a group, to love and care, and to be loved and cared for” (Vander Elst et al., 2012: 254). Satisfaction of individuals’ relatedness need, which suggests their experience of meaningful social connections, can help individuals flourish, whereas their RNF, which implies relational exclusion and loneliness (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Chen et al., 2015) or a sense of lost meaningful social connections (Deci & Ryan, 2000), can erode their resources and cause suboptimal or maladaptive functioning (Trépanier et al., 2016; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013).Footnote 2 When feeling neglected, employees will detect a loss or deficiency in attention and care from their employer and thus perceive reduced work meaning.

Hypothesis 3

Employees’ RNF mediates the relationship between felt neglect and work meaning.

Combining Hypothesis 2 and 3, we propose the following serial mediation hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4

Employees’ RNF and work meaning serially mediate the relationship between felt neglect and OCB.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We conducted a four-wave online study in 2020, starting on March 27 (till March 30; Time 1), with the follow-up studies running on April 10 (till April 13; Time 2), April 24 (till April 27; Time 3) and May 8 (till May 12; Time 4) using a Cloud Research platform with prime panel to obtain a targeted reliable online sample of participants (Chandler et al., 2019). Following the best practices recommended by Aguinis et al. (2021), we recruited participants through this prime panel who were employed and residing in the USA at the time of data collection. To further ensure the high quality of data, we included multiple attention checks throughout the survey (e.g., “If you are reading this carefully, please select “disagree” option, among the scales used). We also screened out participants whose answers were careless based on reverse-coded items in our scales and participants who provided patterned responses to everything (e.g., all 4 s throughout). Finally, we screened out participants who did not fit the eligibility criteria (e.g., those who were not employed or lost the job between the data collection waves, changed their job, work unit, or supervisor). For the sake of the honesty of responses, participants were not aware of the eligibility criteria and were paid regardless of their answers to the eligibility screening questions. Our final sample at Time 1 comprised 276 employed participants who passed the attention checks (response rate = 84%). We invited these participants to participate at Time 2 (response rate = 79%) and used the same screening questions as at Time 1. Only those who were employed and did not change their job, work unit, or supervisor were invited to participate in Time 3 survey (response rate = 73%). We repeated the same procedure for the final data collection at Time 4 (response rate = 72%).

A total of 111 employed US adults from 40 states (52% female; 74.8% White/Caucasian, 8.1% Black/African descent, 9% Asian, 7.2% Hispanic/Latino, and the remaining of other racial/ethnic groups) completed surveys of all four waves and were included in our final sample. Their average age was 38.77 years (SD = 10.14, ranging from 22 to 64). Among them, 56% worked remotely and were employed in a variety of industries, with the biggest categories including 18% in education, 14.4% in IT, 12.6% in finance; 9% in healthcare, 9% in government and 8.1% in manufacturing. Seventy-four percent of our participants worked remotely during the study period. All participants included in the final sample were employed at the start of the study and did not change their job, work unit, or supervisor throughout the data collection period.

Key Measures

All variables were measured in reference to COVID-19 on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), unless specified otherwise.

Felt Neglect

Across four waves, we measured employees’ Felt Neglect by their employer using five items (four adapted from Sanford’s (2010) items and the last one created to capture the essential element of being uncared for). Specifically, participants indicated the extent to which they agreed that during the last two weeks amid the COVID-19 pandemic, they felt “neglected by,” “forgotten by,” “invisible to,” “overlooked by,” and “uncared for by” their employer (Time 1 α = 0.97; Time 2 α = 0.95; Time 3 α = 0.97; and Time 4 α = 0.97).

RNF

At Time 2, we measured participants’ RNF (α = 0.89) since the COVID-19 pandemic affected their work, using Chen et al.’s (2015) four items. We asked participants to indicate the extent they agreed with the following statements (how they felt in their workplace) since the COVID-19 pandemic affected their work: (1) “I have felt excluded from the group I want to belong to”; (2) “I have felt that people who are important to me are cold and distant toward me”; (3) “I have had the impression that people I have spent time with dislike me”; and (4) “I have felt that the relationships I have are just superficial.”

Work Meaning

At Time 3, participants rated Spreitzer’s (1995) three items of Work Meaning (α = 0.97) during the last two weeks on a six-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The three items were: (1) “The work I do is meaningful to me”; (2) “My job activities are personally meaningful to me”; and (3) “The work I do is meaningful to me.”

OCB

At Time 4, we measured participants’ OCB (α = 0.93) during the last two weeks using Dalal and colleagues’ (2009) eight items. Amid a crisis, being a “good citizen” means not only supporting the organization but also helping others. These eight items were: (1) “go out of my way to be a good employee”; (2) “am respectful of my colleagues’ needs”; (3) “display loyalty to my work organization”; (4) “praise or encourage my colleagues”; (5) “volunteer to do something that is not required for my work”; (6) “show genuine concern for my colleagues”; (7) “try to uphold the values of my work organization”; and (8) “try to be considerate to my colleagues.”Footnote 3

Other Measures

Key Control Variable: PCV

Although attention and care are largely need-based and define relationships in terms of concern about one another’s well-being (Ohtsubo et al., 2014), attention and care may be (mis)perceived as obligations promised by employers in their social-exchange-based relationships (McAllister, 1995), particularly amid crises. In other words, while felt neglect is associated with a violation of ethics of care for a need-based relationship, it may be misattributed to a violation of promissory expectations for a social-exchange-based relationship, which will manifest in psychological contract violation (PCV; Morrison & Robinson, 1997). Morrison and Robinson (1997) differentiated PCV (employer intentional reneging on promises) from psychological contract breach (employees’ cognition that one or more promises made by their employer have not been fulfilled for some reason). The negative experience of PCV could make employees view their employment relationship negatively and thus perceive reduced work meaning, which precludes employees’ OCB (Turnley & Feldman, 2000). Given that the employer–employee relationship is largely based on social exchange (Shore et al., 2006), we considered PCV to be a critical control variable tapping an alternative relational mechanism, potentially leading to reduced work meaning. Thus, at Time 2, participants indicated their PCV since the COVID-19 pandemic affected their work, using Robinson and Morrison’s (2000) four items (α = 0.94). The items were: “Since the COVID-19 pandemic affected my work…” (1) “I have been feeling a great deal of anger toward my employer”; (2) “I have been feeling betrayed by my employer”; (3) “I have been feeling that my employer has violated the contract between us”; and (4) “I have been feeling extremely frustrated by how I have been treated by my employer.”

Variables for Robustness Checks: Work Competence, Self-Determination, and Impact

Since Rosso et al. (2010) mentioned the relevance of competence, self-determination, and impact to work meaning, at Time 3 (together with Work Meaning), we also measured participants’ Work Competence (α = 0.89), Self-Determination (α = 0.89) and Impact (α = 0.94) during the past two weeks, using Spreitzer’s (1995) items.

Variables for Psychometric Tests and Robustness Checks: Workplace Ostracism and POS

At Time 2, we measured participants’ Workplace Ostracism (α = 0.95) with Ferris and colleagues’ (2008) six items (appropriate for the COVID-19 context) rated on a seven-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and POS (α = 0.87) since the COVID-19 pandemic affected their work, with Eisenberger et al.’s (2002) three items. Specifically in terms of workplace ostracism, participants indicated the extent to which they felt the following in their work since the COVID-19 pandemic affected their work: “I felt ignored by others”; “I felt avoided by others”; “I felt unnoticed by others”; “I felt shun out by others”; “I felt refused to talk to by others”; and “I felt treated as I were invisible.” We included workplace ostracism for a robustness check because employees might attribute their felt neglect to workplace ostracism. We also included POS for a robustness check because employees might interpret their felt neglect as a lack, or a low level, of organizational support. The three items of POS were: “Since the COVID-19 pandemic affected my work, my organization/employer has… (1) “valued my contribution to its well-being”; (2) “strongly considered my goals and values”; and (3) “really cared about my well-being.”

Results

Reliability and Validity of Felt Neglect Construct

Since we measured felt neglect in all four waves, we examined its test–retest reliability and found supportive evidence (0.61 ≤ rs ≤ 0.83). This construct also exhibited satisfactory and stable internal consistency in all four waves (αs ≥ 0.95). In terms of its convergent and discriminant validity, we examined the relations among felt neglect (Time 1), workplace ostracism, and POS. We followed Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) recommendation and calculated average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR). The cutoff value of AVE is 0.50 and the cutoff value of CR is 0.70 (Hair et al., 2010). We found that felt neglect (Time 1) had an AVE value of 0.87 and a CR value of 0.87, which supported its convergent validity. We established the discriminant validity of felt neglect on the basis of AVE, maximum shared variance (MSV), and average shared variance (ASV), with the criteria for establishing discriminant validity being AVE > MSV, AVE > ASV, and √AVE >|inter-construct correlation| (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2010). We found that the AVE of felt neglect (0.87) was greater than both its MSV (0.39) and ASV (0.32) and its √AVE (0.93) was greater than the absolute value of its correlation with either workplace ostracism (0.51) or perceived organizational support (|-0.62|= 0.62), which supported the discriminant validity of felt neglect. When using felt neglect (Time 2, at which workplace ostracism and POS were measured), we found similar results of construct validity tests. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

We performed confirmatory factor analyses on the five variables—felt neglect, RNF, PCV, work meaning, and OCB. Due to the small ratio of the sample size to the number of items, we used item parceling (Little et al., 2013). All five variables (based on our measures) were uni-dimensional; therefore, we created item parcels based on the order of the items. Specifically, we created two parcels of felt neglect (Items 1–3 and Items 4–5), two parcels of RNF (Items 1–2 and Items 3–4), two parcels of PCV (Items 1–2 and Items 3–4), and three parcels of OCB (Items 1–3, Items 4–6, and Items 7–8). We did not create any parcel for work meaning because it had only three items. The five-factor measurement model fit the data well (χ2 (df = 44) = 53.63, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.03). Then we compared this five-factor model with various alternative models (see Table 2). The five-factor model fit the data better than any of these alternative models. Therefore, the five key variables were distinct from one another.

We also conducted confirmatory factor analyses to further distinguish among felt neglect (Time 1) (the same two parcels as above), workplace ostracism (three two-item parcels created based on the order of the items), and POS. We found that the three-factor model (χ2 (df = 17) = 28.31, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.04) fit better than the two-factor model combining felt neglect and workplace ostracism (χ2 (df = 19) = 262.92, CFI = 0.71, RMSEA = 0.34, SRMR = 0.15), the two-factor model combining felt neglect and POS (χ2 (df = 19) = 146.76, CFI = 0.85, RMSEA = 0.25, SRMR = 0.15), and the two-factor model combining workplace ostracism and POS (χ2 (df = 19) = 151.17, CFI = 0.84, RMSEA = 0.25, SRMR = 0.15). These results further distinguished these three constructs from one another.

Hypothesis Testing

We conducted OLS regression analyses (see Table 3), coupled with PROCESS v3.5 (5,000-replication bootstrapping) in SPSS (Hayes, 2018), without basic demographic variables (e.g., gender and organizational tenure) for the sake of parsimony, as these variables did not change the result patterns. First, we found that employees’ felt neglect was negatively related to their work meaning (Table 3, Model 1), which supported Hypothesis 1. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, using PROCESS v3.5 (Model 4), we found that work meaning mediated the relationship between felt neglect and OCB (indirect effect = −0.20, bootstrap SE = 0.07, bootstrap CI95% [−0.34, −0.07]). We tested the mediating mechanism of RNF stated in Hypothesis 3 while controlling for PCV as a potential alternative mediating mechanism, using PROCESS v3.5 (Model 4). We found that RNF mediated the relationship between felt neglect and work meaning (indirect effect = −0.17, bootstrap SE = 0.07, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.34, −0.05]), whereas PCV had no significant mediating effect (indirect effect = − 0.18, bootstrap SE = 0.11, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.42, 0.03]). Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Then we tested Hypothesis 4 using PROCESS v3.5 (Model 80) and controlling for PCV as an alternative mediating mechanism. We found that RNF and work meaning had a significant serial-mediating effect on the relationship between felt neglect and OCB (indirect effect = −0.08, bootstrap SE = 0.04, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.16, -0.02]), whereas PCV and work meaning serial mediation was not significant (indirect effect = −0.08, bootstrap SE = 0.06, bootstrap CI95% [−0.21, 0.01]). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported. Notably, neither RNF nor PCV had a significant direct relationship with OCB, when work meaning was included as a predictor of OCB. These results suggest the necessity and importance of work meaning and address the potential concerns about RNF (need-based) and PCV (exchange-based) as direct explanations for OCB.

Robustness Checks

Further, we conducted robustness checks. First, we controlled for work competence (Time 3), self-determination (Time 3), and impact (Time 3) as intermediary mechanisms concurrent with work meaning (Time 3) in testing the mediating effect of work meaning on the relationship between RNF and OCB, using PROCESS v3.5 (Model 4). We found that only work meaning (indirect effect = − 0.19, bootstrap SE = 0.09, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.38, −0.04]) mediated the relationship between RNF and OCB, whereas work competence (indirect effect = −0.07, bootstrap SE = 0.06, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.20, 0.01]), self-determination (indirect effect = -0.04, bootstrap SE = 0.04, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.14, 0.03]), and impact (indirect effect = −0.09, bootstrap SE = 0.06, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.22, 0.03]) did not have significant mediating effects.

Second, we added workplace ostracism (Time 2) as a concurrent mediating mechanism as RNF (Time 2) and PCV (Time 2) to test Hypothesis 4, using PROCESS v3.5 (Model 80). We found that RNF and work meaning had a significant serial-mediating effect on the relationship between felt neglect and OCB (indirect effect = − 0.07, bootstrap SE = 0.04, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.17, -0.01]), whereas PCV and work meaning had no significant serial-mediating effect (indirect effect = -0.08, bootstrap SE = 0.06, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.21, 0.01]). The serial-mediating effect of workplace ostracism and work meaning was not significant either (indirect effect = − 0.01, bootstrap SE = 0.04, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.08, 0.07]).

Third, we added POS (Time 2) as a concurrent mediating mechanism as RNF (Time 2) and PCV (Time 2) to test Hypothesis 4, using PROCESS v3.5 (Model 80). We found that RNF and work meaning had a significant serial-mediating effect on the relationship between felt neglect and OCB (indirect effect = − 0.04, bootstrap SE = 0.02, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.10, − 0.01]), whereas PCV and work meaning had no significant serial-mediating effect (indirect effect = -0.04, bootstrap SE = 0.04, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.13, 0.03]). POS and work meaning also had a significant serial-mediating effect (indirect effect = − 0.10, bootstrap SE = 0.04, bootstrap CI95% [− 0.20, − 0.02]).Footnote 4 Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Discussion

By conducting a four-wave online study of working employees in the U.S during the acute (early) stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, we identified the negative relationship-based implications of employees’ felt neglect for their work meaning and subsequent OCB. Our findings suggest that though employers might unintentionally give insufficient attention and care to employees during this crisis, employees’ experience of felt neglect has negative relationship-based implications for their work meaning and subsequent OCB, which could hamper organizational effectiveness amid the COVID-19 crisis. Next, we discuss the theoretical implications of our findings and insights for managerial practice.

Theoretical Implications

As noted earlier, the present research makes theoretical contributions to ethics of care in employment contexts and Rosso et al.’s (2010) work meaning theory. First, the present research stresses the largely neglected ethics of care in employment contexts. Ethics of justice, which emphasizes fairness and reciprocity, has been a dominant logic for social exchange-based relationships, in which employers are expected to apply unbiased standards to provide clarity, certainty, and impartial judgments of behaviors and performance. In contrast, ethics of care stresses “responsiveness to the complex and subjective nature of relational experiences” (Simola, 2003: 354), and emphasizes the importance of ongoing, interdependent relationships as loci of care (Branicki, 2020; Lawrence & Maitlis, 2012; Sevenhuijsen, 2003). From the perspective of ethics of care, it becomes a moral concern when organizations are not responsive to their employees’ needs (Gilligan, 1982). This is exactly what we found about employees’ experiences and behaviors in response to their felt neglect.

Ethics of care is particularly important to crisis management within employment contexts. In contrast to traditional perspectives on crisis management, the one grounded in ethics of care focuses more on relational logic, subjective and situated understanding, and ongoing attention to relationships (Ciulla, 2009). This perspective shift provides new ways of understanding crisis management. Indeed, our findings acknowledge the subjective and situational nature of employees’ perception of being neglected by their employer, which varies across employees and depends on their idiosyncratic relationship with their employer. Our findings also demonstrate that employees who feel neglected use relational logic, indicated by relatedness need frustration, in deriving work meaning and deciding on OCB. In this sense, our research stresses the importance of ethics of care in employment contexts particularly amid crises.

Second, our findings extended Rosso et al.’s (2010) work meaning theory in several ways. Compared to other factors such as self-efficacy and social impact, as well as organizational values, mission, and socio-moral climate (e.g., Cassar & Meier, 2018; Schnell et al., 2013), empirical attention to relational pathways to work meaning, particularly during crises and other uncertain events (McGregor et al., 2010; Simon et al., 1998), has been relatively scarce. Employees are embedded in a network of social relationships in organizations, which serve as the bases for their moral reasoning and understanding of situations. However, relational hindrances to work meaning are under-explored. The present research helps bridge this theoretical gap by showing that felt neglect can be a relational hindrance to work meaning through RNF (i.e., a need-based relational hindrance) rather than PCV (i.e., an exchange-based relational hindrance). In addition, our findings not only provide more precision to Rosso et al.’s (2010) work meaning theory, but also speak to Ward and King’s (2017: 75) claim that research has largely focused on the conceptualization of work meaning and the positive organizational outcomes of work meaning, and yet “[m]uch remains to be known about the organizational factors and experiences that contribute to perceptions that one’s work is meaningful.” Ward and King (2017) asked what promotes work meaning; likewise, the question about what hinders work meaning is as important. We have empirically demonstrated that felt neglect differs from perceived workplace ostracism and POS amid the COVID-19 pandemic and operates as a robust hindrance to work meaning. Various issues associated with hindrances to work meaning warrant further research attention. Furthermore, as noted earlier, work meaning theory (Rosso et al., 2010) has a limited focus on the outcomes of work meaning. Our research shows that work meaning is predictive of important work behaviors such as OCB. By doing so, we enrich Rosso et al.’s (2010) work meaning theory and encourage scholars to examine other important outcomes of work meaning.

Strengths, Limitations and Direction for Future Research

Although we (a) tested the internal consistency, test–retest reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of employees’ felt neglect and (b) controlled for work competence, self-determination, and impact while demonstrating the intermediary role of work meaning, which are the two notable strengths of our study, our findings should be viewed in light of two study limitations. First, due to resource constraints amid COVID-19, all the variables were self-reported, raising the concern about common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). On the other hand, all the variables in our model, perhaps except for OCB, should be reported by employees, as they tap into employees’ intrapsychic experiences and employees should have the best knowledge of those experiences. Moreover, prior research has found that self-reported OCB is correlated with supervisor-rated OCB (e.g., O’Brien & Allen, 2008), and amid COVID-19, their leader might not have the opportunity to observe our participants’ OCB, given that many of them were working from home. As O’Brien and Allen (2008) noted, although self-ratings are susceptible to social desirability bias, employees have the best knowledge of their OCB. Even though supervisor ratings can help reduce common method bias, supervisors have restricted knowledge about employees’ OCB, or may have different performance models, and are susceptible to the halo error. That said, we encourage replication and extension studies using supervisor-rated employee OCB. Second, although we separated and sequenced the variables temporally and performed separate tests including variables for robustness checks (Podsakoff et al., 2012), which could help reduce common method bias, we encourage future research to use experimental study designs to generate stronger causal evidence.

Despite the above limitations, we offer four additional promising directions for future research. First, felt neglect may be as common as workplace ostracism. Work meaning theory is merely one framework that helps explain the implications of employees’ felt neglect. Future research can draw upon other frameworks to examine its implications for in-role, proactive, and deviant behaviors. Second, Wrzesniewski et al.’s (2003) model suggests that interpersonal acts at work and the traces from these acts can shape work meaning, and these acts can be direct and explicit, such as uncivil behaviors, or indirect and subtle, such as facial expressions. Reading interpersonal cues associated with felt neglect and interpret them in relation to work meaning may entail complex psychological mechanisms. We encourage future research to explore the mechanisms, implications, and boundary conditions of interpersonal sensemaking and work meaning (Wrzesniewski et al., 2003) with the notion of felt neglect. Third, although we focused on RNF as a core, need-based relational mechanism (while accounting for PCV as an alternative relational mechanism), we did not intend to claim that RNF was the only possible relational mechanism leading to work meaning (Rosso et al., 2010). We encourage researchers to explore other relational mechanisms (e.g., affective commitment and trust; Colquitt et al., 2016) ensuing from felt neglect. Research that focuses on various relational mechanisms may offer additional insights into the determinants of work meaning. Moreover, Rosso et al. (2010) argued that clear organizational missions or ideologies can give employees the purpose of their work; when employees act in accordance with their values, they can have a sense of assurance about the consistency between their behaviors and values. Finally, future research can explore potential boundary conditions for the serial mediation process proposed in the current research. For example, can employees’ attributions of blame for felt neglect (e.g., the employer’s intentional versus unintentional neglect) alter the strengths of the effects of felt neglect on subsequent outcomes? Such research effort can shed light on how employees can maintain work meaning and engagement in constructive behaviors in the face of negative work conditions or experiences.

Practical Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused turmoil in organizations and in people’s lives. In times like this, every employee matters. Employee OCB can be instrumental to organizational survival and recovery. At the same time, employees turn to their employer for attention and care amid crises. The COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. Ethics of care amid the COVID-19 pandemic should apply to all employees and employers, regardless of the industry and type of business they are in. Even though it is understandable that employers’ may unintentionally neglect employees due to their devotion of finite attention resources to saving and recovering their business, through neglect, employees will perceive employers as violating ethics of care, which will create detrimental outcomes to employee well-being and behavior and, ultimately, to employers themselves. Notably, our study participants work in a wide range of industries; therefore, our findings and associated practical insights are relevant to diverse experiences of employees. We encourage employers to provide as much attention and care as possible to employees and this care does not necessarily have to be complex or very time-consuming. Rather, based on our study participants’ comments, it may require only some simple steps. For example, many employees expressed their desire for information, guidance, and clear communication amid COVID-19. This is consistent with Lawrence and Maitlis’ (2012) claim that care can be enacted through discursive practices and everyday working relationships, which promote employees’ sense of relatedness or belongingness. Accordingly, keeping communication channels open, such as sending emails that provide information and guidance, along with periodic check-ins and feedback seeking, may help mitigate employees’ feeling of being neglected. These actions should lead to a “win–win” situation in which employees have better relational experiences and perceive stronger work meaning, whereas employers receive more discretionary efforts and contributions from their employees.

Notes

As Trépanier et al., (2016: 692) noted, “the harmful effects of work environments characterized by control, reprimands, and rejection may extend beyond lack of basic need satisfaction…to frustration of employees’ psychological needs. Need frustration would therefore be a more adequate concept for capturing the effects of negative social environments, such as exposure to workplace bullying, on employees’ psychological needs and explain consequent manifestations of poor psychological functioning.”.

We conducted supplementary analyses for OCBO (Items 1, 3, 5, and 7) and OCBI (Items 2, 4, 6, and 8) separately. The patterns of the key results did not change.

The Appendix presents our endogeneity tests.

References

Aguinis, H., Villamor, I., & Ramani, R. S. (2021). MTurk research: Review and recommendations. Journal of Management, 47(4), 823–837.

Allan, B. A., Batz-Barbarich, C., Sterling, H. M., & Tay, L. (2019). Outcomes of meaningful work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 500–528.

Antonakis, J., Banks, G. C., Bastardoz, N., Cole, M. S., Day, D. V., Eagly, A. H., et al. (2019). The Leadership Quarterly: State of the Journal. Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), 1–9.

Aselage, J., & Eisenberger, R. (2003). Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: A theoretical integration. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 491–509.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2002). The pursuit of meaningfulness in life. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 608–628). Oxford University Press.

Belkin, L. Y., & Kong, D. T. (2021). Supervisor companionate love expression and elicited subordinate gratitude as moral-emotional facilitators of voice amid COVID-19. Journal of Positive Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1975157

Branicki, L. J. (2020). COVID-19, ethics of care and feminist crisis management. Gender, Work and Organization, 27, 872–883.

Cartwright, S., & Holmes, N. (2006). The meaning of work: The challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Human Resource Management Review, 16(2), 199–208.

Cassar, L., & Meier, S. (2018). Nonmonetary incentives and the implications of work as a source of meaning. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32(3), 215–238.

Chandler, J., Rosenzweig, C., Moss, A. J., Robinson, J., & Litman, L. (2019). Online panels in social science research: Expanding sampling methods beyond Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods, 51(5), 2022–2038.

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., et al. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236.

Christianson, M. K., & Barton, M. A. (2021). Sensemaking in the Time of COVID-19. Journal of Management Studies, 58(2), 572–576.

Clark, M. S., Mills, J., & Powell, M. C. (1986). Keeping track of needs in communal and exchange relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(2), 333–338.

Clore, G. L., Gasper, K., & Garvin, E. (2001). Affect as information. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Handbook of affect and social cognition (pp. 121–144). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Colquitt, J. A., Baer, M. D., Long, D. M., & Halvorsen-Ganepola, M. D. K. (2016). Scale indicators of social exchange relationships: A comparison of relative content validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 599–618.

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49, 173–208.

Chun, R. (2005). Ethical character and virtue of organizations: An empirical assessment and strategic implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 57(3), 269–284.

Ciulla, J. B. (2009). Leadership and the ethics of care. Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 3–4.

Dalal, R. S., Lam, H., Weiss, H. M., Welch, E. R., & Hulin, C. L. (2009). A within-person approach to work behavior and performance: Concurrent and lagged citizenship-counterproductivity associations, and dynamic relationships with affect and overall job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 1051–1066.

Daryanto, A. (2020). EndoS: An SPSS macro to assess endogeneity. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 16, 56–70.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Dutton, J. E., Ashford, S. J., Lawrence, K. A., & Miner Rubino, K. (2002). Red light, green light: Making sense of the organizational context for issue selling. Organization Science, 13, 355–372.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507.

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C., Sucharski, I. L., & Rhoades, L. (2002). Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 565–573.

Farrell, D. (1983). Exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect as responses to job dissatisfaction: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 26(4), 596–607.

Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W., & Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the Workplace Ostracism Scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1348–1366.

Forgas, J. P. (1995). Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 39–66.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 382–388.

George, J. M., & Zhou, J. (2007). Dual tuning in a supportive context: Joint contributions of positive mood, negative mood, and supervisory behaviors to employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 605–622.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice. Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Bowler, W. M. (2007). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 93–106.

Harvey, S., & Haines, V. Y. I. I. I. (2005). Employer treatment of employees during a community crisis: The role of procedural and distributive justice. Journal of Business and Psychology, 20(1), 53–68.

Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46, 1251–1271.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford.

Hayes, A. F., & Cai, L. (2007). Using heteroskedasticity-consistent standard error estimators in OLS regression: An introduction and software implementation. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 709–722.

Heintzelman, S. J., & King, L. A. (2014). Life is pretty meaningful. American Psychologist, 69, 561–574.

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice and loyalty: Responses of decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

Hui, C., Lee, C., & Rousseau, D. M. (2004). Psychological contract and organizational citizenship behavior in China: Investigating generalizability and instrumentality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 311–321.

Lawrence, T. B., & Maitlis, S. (2012). Care and possibility: Enacting an ethic of care through narrative practice. Academy of Management Review, 37, 641–663.

Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 131–142.

Lepisto, D. A., & Pratt, M. G. (2017). Meaningful work as realization and justification: Toward a dual conceptualization. Organizational Psychology Review, 7, 99–121.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2000). An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relations between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 407–416.

Liu, B. F., Shi, D., Lim, J. R., Islam, K., Edwards, A. L., & Seeger, M. (2021). When crises hit home: How US higher education leaders navigate values during uncertain times. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04820-5

Lips-Wiersma, M., & Wright, S. (2012). Measuring the meaning of meaningful work: Development and validation of the comprehensive meaningful work scale (CMWS). Group & Organization Management, 37(5), 655–685.

Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K., & Schoemann, A. M. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods 18(3), 285–300. Maitlis, S. (2004). Taking it from the top: How CEOs in fluence (and fail to influence) their boards. Organization Studies, 25, 1275–1311.

Maitlis, S., & Christianson, M. (2014). Sensemaking in organizations: Taking stock and moving forward. Academy of Management Annals, 8, 57–125.

Maitlis, S., & Lawrence, T. B. (2007). Triggers and enablers of sensegiving in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 57–84.

Maitlis, S., & Sonenshein, S. (2010). Sensemaking in crisis and change: Inspiration and insights from Weick (1988). Journal of Management Studies, 47, 551–580.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59.

McAllister, D. J., & Bigley, G. A. (2002). Work context and the definition of self: How organizational care influences organization-based self-esteem. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5), 894–904.

McGregor, I., Nash, K., Mann, N., & Phills, C. E. (2010). Anxious uncertainty and reactive approach motivation (RAM). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 133–147.

Morrison, E. W., & Robinson, S. L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 226–256.

Naus, F., van Iterson, A., & Roe, R. (2007). Organizational cynicism: Extending the Exit, Voice, Loyalty, and Neglect Model of employees’ responses to adverse conditions in the workplace. Human Relations, 60(5), 683–718.

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. University of California Press.

O’Brien, K. E., & Allen, T. D. (2008). The relative importance of correlates of organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior using multiple sources of data. Human Performance, 21(1), 62–88.

Ohtsubo, Y., Matsumura, A., Noda, C., Sawa, E., Yagi, A., & Yamaguchi, M. (2014). It’s the attention that counts: Interpersonal attention fosters intimacy and social exchange. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35(3), 237–244.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington Books.

Peeters, G. & Czapinski, J. (1990). Positive-negative asymmetry in evaluations: The distinction between affective and informational negativity effects. European Review of Social Psychology 1, 33–60.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

Pratt, M. G., & Ashforth, B. E. (2003). Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 309–327). Berrett-Koehler.

Pfeffer, J. (1981). Management as symbolic action: The creation and maintenance of organisational paradigms. Research in Organizational Behavior, 3, 1–52.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698–714.

Robertson, K. M., O’Reilly, J., & Hannah, D. R. (2020). Finding meaning in relationships: The impact of network ties and structure on the meaningfulness of work. Academy of Management Review, 45(3), 596–619.

Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 574–599.

Robinson, S. L., O’Reilly, J., & Wang, W. (2013). Invisible at work: An integrated model of workplace ostracism. Journal of Management, 39(1), 203–231.

Robinson, S. L., & Morrison, E. W. (2000). The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 525–546.

Robinson, S. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 245–259.

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127.

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Sage.

Rousseau, D. M. (2001). Schema, promise and mutuality: The building blocks of the psychological contract. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74(4), 511–541.

Rusbult, C. E., Farrell, D., Rogers, G., & Mainous, A. G. (1988). Impact of exchange variables on exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect: An integrative model of responses to declining job satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 31(3), 599–627.

Rusbult, C. E., Zembrodt, I. M., & Gunn, L. K. (1982). Exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect: Responses to dissatisfaction in romantic involvements. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(6), 1230–1242.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). The darker and brighter sides of human existence: Basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 319–338.

Sanford, K. (2010). Perceived threat and perceived neglect: Couples’ underlying concerns during conflict. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 288–297.

Schnell, T., Höge, T., & Pollet, E. (2013). Predicting meaning in work: Theory, data, implications. Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(6), 543–554.

Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (1983). Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 513–523.

Sevenhuijsen, S. (2003). The place of care: The relevance of the feminist ethic of care for social policy. Feminist Theory, 4(2), 179–197.

Shore, L. M., Tetrick, L. E., Lynch, P., & Barksdale, K. (2006). Social and economic exchange: Construct development and validation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 837–867.

Simola, S. (2003). Ethics of justice and care in corporate crisis management. Journal of Business Ethics, 46, 351–361.

Simon, L., Arndt, J., Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1998). Terror management and meaning: Evidence that the opportunity to defend the worldview in response to mortality salience increases the meaningfulness of life in the mildly depressed. Journal of Personality, 66(3), 359–382.

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465.

Staiger, D., & Stock, J. H. (1997). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica, 65, 557–586.

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20, 322–337.

Stephenson, J. (March 31, 2020). Social care staff on coronavirus frontline “feel forgotten.” Nursing Times. Available at: https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/social-care/social-care-staff-on-coronavirus-frontline-feel-forgotten-31-03-2020/

Stillman, T. F., & Baumeister, R. F. (2009). Uncertainty, belongingness, and four needs for meaning. Psychological Inquiry, 20, 249–251.

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2013). The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48, 345–355.

Storey, J. E. (2020). Risk factors for elder abuse and neglect: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 50, 101339.

John, B., & Pearson, Y. E. (2016). Crisis management ethics: Moving beyond the public-relations-person-as-corporate-conscience construct. Journal of Media Ethics, 31, 18–34.

Thomas, J. C., & Dasgupta, N. (2020). Ethical pandemic control through the public health code of ethics. American Journal of Public Health, 110(8), 1171–1172.

Thomas, J. C., & Young, S. (2011). Wake me up when there’s a crisis: Progress on state pandemic influenza ethics preparedness. American Journal of Public Health, 101(11), 2080–2082.

Trépanier, S.-G., Fernet, C., & Austin, S. (2016). Longitudinal relationships between workplace bullying, basic psychological needs, and employee functioning: A simultaneous investigation of psychological need satisfaction and frustration. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(5), 690–706.

Tronto, J. (2006) Women and caring: What can feminists learn about morality from caring? In V. Held (Ed.), Justice and care: Essential readings in feminist ethics. Boulder, CO: Westview

Turnley, W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (1999). The impact of psychological contract violations on exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect. Human Relations, 52(7), 895–922.

Turnley, W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2000). Re-examining the effects of psychological contract violations: Unmet expectations and job dissatisfaction as mediators. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(1), 25–42.

Vander Elst, T., Van den Broeck, A., De Witte, H., & De Cuyper, N. (2012). The mediating role of frustration of psychological needs in the relationship between job insecurity and work-related well-being. Work & Stress, 26(3), 252–271.

Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(3), 263–280.

Ward, S. J., & King, L. A. (2017). Work and the good life: How work contributes to meaning in life. Research in Organizational Behavior 37, 59–82. Waters, L., Algoe, S. B., Dutton, J., Emmons, R., Fredrickson, B. L., Heaphy, E., Moskowitz, J. T., Neff, K., Niemiec, R., Pury, C., & Steger, M. (2021) Positive psychology in a pandemic: buffering, bolstering, and building mental health. Journal of Positive Psychology

Waters, L., Cameron, K., Nelson-Coffey, S. K., Crone, D. L., Kern, M. L., Lomas, T., et al. (2021). Collective wellbeing and posttraumatic growth during covid-19: How positive psychology can help families, schools, workplaces and marginalized communities. The Journal of Positive Psychology. Advance online publication.. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1940251.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 82–111.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Sage.

Withey, M. J., & Cooper, W. H. (1989). Predicting exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34(4), 521–539.

Wrzesniewski, A., Dutton, J. E., & Debebe, G. (2003). Interpersonal sensemaking and the meaning of work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 93–135.

Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, careers, and calling: People’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 21–33.

Wrzesniewski, A., LoBuglio, N., Dutton, J. E., & Berg, J. M. (2013). Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. In A. B. Bakker (Ed.), Advances in positive organizational psychology (pp. 281–302). Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2046-410X(2013)0000001015.

Zhao, H., Wayne, S. J., Glibkowski, B. C., & Bravo, J. (2007). The impact of psychological contract breach on work-related outcomes: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 60, 647–680.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study involving human participants was done explicitly by a university institutional review board. All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all human participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

We included General Angry Mood as an instrumental variable for our endogeneity tests. Both RNF and PCV could be associated with employees’ general angry mood. First, employees might use their general angry mood as information regarding their negative work environment in rating their RNF and PCV (Clore et al., 2001; Forgas, 1995; Schwarz & Clore, 1983). Second, general angry mood might reduce concerns for achievement and status and increase relational concerns (Halbesleben & Bowler, 2007). Third, general angry mood could make individuals more attuned to negative interpersonal treatment (Peeters & Czapinski, 1990). Following George and Zhou (2007) who used a PANAS scale (Watson et al., 1988) to assess mood, at Time 1, we asked participants to indicate their General Angry Mood (α = 0.67) by rating two items (“hostile” and “irritated”) from a shortened PANAS scale on a seven-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). When controlling for felt neglect, general angry mood, as expected for an instrumental variable, was not significantly correlated with RNF (partial r = 0.14, p = 0.151), PCV (partial r = 0.16, p = 0.100), or work meaning (partial r = − 0.11, p = 0.261).

We conducted two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression analyses (Antonakis et al., 2019; Daryanto, 2020) (using HC4 for robust standard errors; Hayes & Cai, 2007), coupled with Hausman’s (1978) specification test and the weak instrument test (Staiger & Stock, 1997). We found that endogeneity concerns should not pose threat to our findings. First, with RNF or PCV being the dependent variable, felt neglect being the independent variable, and general angry mood being the instrumental variable in a 2SLS regression analysis, we found that general angry mood was a strong instrument (Cragg-Donald F = 19.49) and an OLS regression analysis would be efficient (given that all estimates of all residuals were zero). Therefore, an endogeneity concern should not affect the relationships between felt neglect and RNF and between felt neglect and PCV.

Second, with work meaning being the dependent variable, felt neglect being the independent variable, and general angry mood being the instrumental variable in a 2SLS regression analysis, we found that general angry mood was a strong instrument (Cragg-Donald F = 19.49) and an OLS regression analysis would be efficient. Therefore, an endogeneity concern should not affect the relationship between felt neglect and work meaning.

Third, when controlling for work meaning, neither RNF (partial r = -0.11, p = 0.252) nor PCV (partial r = 0.13, p = 0.168) were significantly correlated with OCB. With OCB being the dependent variable, work meaning being the independent variable, and RNF being the instrumental variable in a 2SLS regression analysis, we found that RNF was a strong instrument (Cragg-Donald F = 38.47) and an OLS regression analysis would be efficient. With OCB being the dependent variable, work meaning being the independent variable, and PCV being the instrumental variable in a 2SLS regression analysis, we found that PCV was a strong instrument (Cragg-Donald F = 24.82) and an OLS regression analysis would be efficient. Taken together, these results suggested that an endogeneity concern should not affect the relationship between work meaning and OCB.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, D.T., Belkin, L.Y. You Don’t Care for me, So What’s the Point for me to Care for Your Business? Negative Implications of Felt Neglect by the Employer for Employee Work Meaning and Citizenship Behaviors Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Bus Ethics 181, 645–660 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04950-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04950-w