Abstract

Background

The sudden and unexpected pandemic changed the daily routine of the children with cerebral palsy (CP) and their caregivers.

Aims

This study aimed to investigate the impact of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on the utilization of health and rehabilitation services and the general health and physical status of children with CP. In addition, the second aim of the study was to examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on caregivers’ quality of life (QOL) and their fear of COVID-19.

Methods

The utilization of children health and rehabilitation services during the pandemic, the general health and physical status of the children during the pandemic, and the children and caregivers’ history of COVID-19 infections were questioned. Furthermore, the caregivers’ level of fear of COVID-19 and their QOL were examined.

Results

One hundred twenty caregivers were contacted by phone, and 94 (78.33%) caregivers agreed to participate in the study. Sixty-three of 94 children (67.1%) did not attend their routine control check-up during the pandemic. Twelve children (12.8%) discontinued their physical therapy sessions during the pandemic. Caregivers physical and mental QOL significantly decreased during the pandemic (p < 0.05). The median of caregivers’ Fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19S) was 17.5 (7–35).

Conclusion

We think that more attention should be given to telerehabilitation and telemedicine services of the clinicians who deal with the children with CP, and their caregivers in order to prevent the negative effects of future pandemic periods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In December 2019, the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) was first detected in Wuhan, China. The COVID-19 outbreak then spread across the world [1]. In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported more than 118,000 cases of COVID-19 worldwide and declared the situation to be a pandemic [2]. Since there was no treatment method or vaccine available for COVID-19, preventive health campaigns such as social distancing were implemented in many countries [3]. The first case in Turkey was diagnosed on March 11, 2020 [4]. Following the detection of the first case in Turkey, face-to-face education was suspended in schools, intercity travel restrictions were introduced, and cafes, bars, and restaurants, which are possible sites of contamination, were closed, and curfews, were applied for people over 65 and under 20 years old [5].

The sudden and unexpected lockdown changed the daily routine of the children with cerebral palsy (CP) and their caregivers in Turkey, as in the rest of the world [3]. Children with CP require physiotherapy regularly, repeated botulinum toxin injections, and if needed orthopedic surgery to maximize their developmental potential and minimize musculoskeletal deformity throughout their life [6]. Many rehabilitation centers and special education and rehabilitation centers for disabled children slowed down their activities, in response to the social distancing measures implemented in order to reduce the spread of the infection through the population [7, 8]. The fact that children with CP were required to stay away from rehabilitation services for a long time may adversely affect their functionality, mental health, and psychological status [9].

Of course, the social isolation that accompanied social distancing did not only affect children but also affected the general health and mental health of their caregivers [10]. The caregivers of children with CP are already reported to have a lower quality of life (QOL) [11]. In addition, a relationship has been found between caregivers’ QOL and the severity of motor impairments, the emotional and behavioral problems of children with CP, the general mental health of caregivers, parenting stress, and environmental problems [11]. The caregivers of children with CP, who already faced the challenges of providing for a disabled child, experienced additional negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the effects of lockdown on their mental health and economic burdens due to pandemic [1, 12]. Furthermore, children with chronic and developmental diseases such as CP have a higher risk for infection and transmission of COVID-19, which may further stress their caregivers [13].

The high infection and mortality rates of COVID-19 have caused new health problems such as fear of COVID-19[14]. It has been found that female gender, being married, lower educational status, and being a health care worker were factors which increased the probabilities of having a high level of fear of COVID-19 [15].

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with CP and the physicological burden on caregivers has been investigated, but caregivers’ QOL and fears related to the COVID-19 pandemic have not yet been investigated. Therefore, the first aim of this study was to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the utilization of health and rehabilitation services and the general health and physical status of children with CP in our study population. In addition, the second aim of the study was to examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on caregivers’ QOL and their fear of COVID-19.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the University of Health Sciences, Local Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval number: 105/04) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. Signed informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to starting data collection.

Participants

The participants included children with diagnosed CP, between 2 and 18 years of age and who had been followed-up since before the pandemic in our pediatric rehabilitation outpatient clinic. The study also included the participating children’s primary caregivers, who agreed to participate in the study, whose contact information was accessible, whose pre-pandemic information was recorded in the children’s documents (especially results of quality of life), and who did not have communication problems. One hundred twenty caregivers were contacted by phone, and 94 (78.33%) caregivers agreed to participate in the study. Therefore, the study included 94 participants.

Data collection

This study was conducted in the pediatric rehabilitation outpatient clinic of our hospital. In our pediatric rehabilitation outpatient clinic, children with diseases such as CP, spina bifida, and muscular dystrophy are regularly followed-up every 3 or 6 months. Between the dates of March 15, and May 31, 2020, our pediatric rehabilitation outpatient clinic was stopped for the elective use of healthcare services. As of June 1, 2020, our pediatric rehabilitation outpatient clinic was reopened with an appointment system in accordance with the pandemic conditions.

A questionnaire which queried the demographic characteristics of children, the general information of caregivers, the utilization of children health and rehabilitation services during the pandemic, the general health and physical status of the children during the pandemic, and the children and caregivers’ history of COVID-19 infections was developed for this study. Furthermore, the caregivers’ level of fear of COVID-19 and their QOL were examined. While some parts of the questionnaire were completed using data from the children’s medical documents, the remaining information was provided by caregivers over the phone. Data were collected from December 1, 2020, to January 15, 2021. However, the participants were asked to answer the questions based on the period of time between March 15, and November 30, 2020. Data collection, including contacted the caregivers by phone, was carried out by two different physicians. One physician collected data from the documents of the patients, and the other called the caregivers.

Demographics of children and general characteristics of caregivers

The children’s age, gender, type of CP, Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) level, and the caregivers’ age, education level, and occupation were obtained from the medical documents. The children and caregivers’ history of COVID-19 infection and information such as changes in caregivers’ employment status were obtained by phone.

Utilization of children health services during pandemic

The caregivers were asked to report the number of visits to our pediatric rehabilitation outpatient clinic, the reasons for those visits, whether there were any irregular follow-up visits, the reasons for those irregular follow-up visits, the status of continuing physical therapy, the duration of any breaks in physical therapy, the level of difficulty in obtaining oral medication, the use of orthosis, and whether their children had visited the hospital for any other reason between March 15, 2020, and January 1, 2020.

The children’s general health and physical status during the COVID-19 pandemic

The caregivers were asked to evaluate their children’s general health, mobility, spasticity, joint motion, social function, communication, and emotional state during the pandemic. Responses were reported as worse, the same or better since the start of the pandemic.

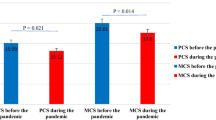

Caregivers’ quality of life

The caregivers’ QOL before and during the pandemic was evaluated using Short Form-12 (SF-12), a scale which includes 12 items and 2 components: physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) [16]. The caregivers’ SF-12 results between October 15, 2019, and March 15, 2020, were obtained from the children’s medical documents and used to evaluate their QOL before the pandemic. The caregivers’ QOL during the pandemic were investigated by phone.

Fear of COVID-19

The caregivers’ fear of COVID-19 was examined using FCV-19S, which is a 7-point scale for which each question is scored between 1 and 7. The total score differs from 7 to 35, and higher scores indicate higher levels of fear. The Turkish language adaptation of FCV-19S was previously developed [17]. The cut-off point for fear related to COVID-19 was determined as 16.5 [18], and responses above the cut-off value were defined as extreme fear. The relationship between FCV-19S responses, children’s age and GMFCS levels, and caregivers’ age, education level, and changes in QOL were analyzed. Moreover, the effect of a history of COVID-19 infection in children and caregivers on FCV-19S responses and the fear of COVID-19 on follow-up routine appointments and physiotherapy sessions were examined.

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 22.0 for Windows) software. The variables were investigated using visuals (histograms and probability plots) and a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. In reporting descriptive statistics, data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (minimum–maximum) for continuous variables, and as frequencies and percentages (%) for nominal and categorical variables. The results pertaining to the caregivers’ QOL before and during the pandemic were compared using paired sample t tests. Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted to compare the change in QOL between caregivers with and without a history of COVID-19 infection and caregivers with and without a change in employment. Additionally, Mann-Whitney U tests were also used to compare the FCV-19S results of caregivers with and without a history of COVID-19 infection and whose children did and did not receive irregular follow-up visits and whose children did and did not have a history of COVID-19 infection. A Kruskal Wallis test was used to compare the COVID-19 fear levels of caregivers whose children continued, took a break, and discontinued physiotherapy. Spearman correlation tests were performed to analyze the relationship between the education level of caregivers, age of children, age of caregivers, GMFS levels of children, change in caregivers’ QOL, and FVC-19S results.

Results

Five of the children (5.3%) and 13 (13.8%) of the caregivers had a history of COVID-19 infection. Eighteen of the 94 caregivers changed their jobs during the pandemic. The median score of the FCV-19S was 17.5, and 51.1% of caregivers had extreme fear of COVID-19. Tables 1 and 2 show the demographics of children and the general characteristics of caregivers.

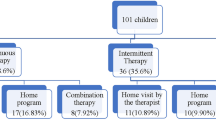

Sixty-three (67.1%) children did not attend their routine control check-up during the pandemic. Nine of the children (9.6%) received botulinum toxin injections during the pandemic. Only one of the children experienced side effects from the botulinum toxin (subfebril fewer) (Table 3).

Eighty-one (86.1%) caregivers reported that their children had irregular follow-up visits. The most common reason for the irregular follow-up visits was fear of COVID-19 transmission or infection. Thirty-two children (34%) had no break in their routine physical therapy sessions, while 50 (53.2%) children had a break in their routine physical therapy sessions but still continued their sessions. Twelve children (12.8%) discontinued their physical therapy sessions during the pandemic. Thirty (31. 9%) children visited the hospital for other reasons, and the most common reason for visiting the hospital was orthopedic surgery (11 children (11.7%)). Twenty-nine (30.9%) children could not continue using their orthosis during the pandemic (Table 3).

Most of the caregivers reported that their children’s general health (45.7%), mobility (55.4%), spasticity (58.5%), joint motion (61.7%), social function and communication (51.1%), and mood (55.4%) were worse during the pandemic compared before (Fig. 1).

Caregivers physical and mental QOL significantly decreased during the pandemic (p = 0.001, p = 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Table 4 shows the effects of a history of COVID-19 infection and a change in employment on caregivers’ QOL. The PCS-12 scores of the caregivers with a history of COVID-19 infections were significantly lower than the caregivers without a history of COVID-19 infection.

There was no correlation between FCV-19S results and the education level of caregivers, age of children, age of caregivers, GMFS levels of children, change in PCS-12 scores, and MCS-12 scores (p > 0.05) (Table 5).

No significant differences were found in the COVID-19 fear levels of caregivers whose children did and did not receive irregular follow-up visits; whose children were still continuing, took a break, and discontinued physiotherapy; and whose children did and did not have a history of COVID-19 infection (p = 0.09, p = 0.57, p = 0.41 respectively).

Discussion

The results of this study revealed that most of the participating children did not continue their routine follow-up outpatients control visits during the COVID-19 pandemic, and most of them had to take a break in their physical therapy sessions. Caregivers mostly reported that the general health, mobility, spasticity, joint motion, communication, and mood of the children with CP were negatively affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted the caregivers’ physical and mental QOL, and the physical quality of caregivers with a history of COVID-19 infection decreased more than the caregivers without a history of COVID-19 infection. Furthermore, the fear level of COVID-19 did not affect the caregivers’ QOL, and the education level of caregivers, age of children, age of caregivers, and GMFS levels of children were not found to be factors which had an effect on caregivers’ fear levels of COVID-19.

A study in France showed that 77% of children’s medical consultations were cancelled or postponed during the lockdown. Moreover, only 48%, 27%, 32%, 31%, and 13% of children, respectively, continued their physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, psychomotor therapy, and orthopedic sessions [3].

Only 5.9% of 68 children continued conventional physiotherapy; 19 (27.9%) of 68 children discontinued their conventional program, and telerehabilitation and indirect remote supervision were used in 23.5% (16/68) and 42.6% (29/68) of cases, respectively, in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. The average hours of rehabilitation decreased from 3.5 to 2.5 h during the pandemic in Italy [9].

In the current study, 12.9% and 53.2% of 94 children discontinued or took a break from their physiotherapy sessions, respectively. The median duration of a break in physiotherapy sessions was 3.00 months. Moreover 86.2% of 94 patients were found to have disruptions in their routine follow-up control visits, and the most common reasons for having disruptions in routine follow-up control visits were fear of catching COVİD-19 infection, and scheduling problems. In our country, as in the rest of the world, rehabilitation centers were closed in March, April, and May 2020 and elective health services were slowed down in order to use health services effectively [8].

The negative effects of lockdown on children’s mental health, wellbeing, and social health (morale, behavior, social interaction, and physical activity) were highlighted in a French survey study [19].

The caregivers who participated in the current study mostly reported that the general health, mobility, spasticity, joints motions, communication, and mood of their children were worse during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic period.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused changes to children’s daily routines [20]. During this period, children with and without disabilities had to be out of school, were less physically active, had more screen time, and had irregular bedtimes and mealtimes. Thus, these lifestyle changes have caused psychosocial stress on children [20]. This psychosocial stress has more greatly affected the daily life of children with CP who have a higher risk of COVID-19 transmission and infection [3].

Another alteration in the daily routines of children with CP has been that COVID-19 has interrupted the activities of rehabilitation, and special education and rehabilitation centers for disabled children. The absence of rehabilitation may lead to the inevitable deteriorate of the child’s physical status and functional ability [1, 3].

The results of our study and those obtained from other studies highlight the importance of telemedicine and telerehabilitation in providing distance healthcare to overcome the challenges resulting from COVID-19 social distancing practices [19]. While remote healthcare solutions cannot replace face-to-face medical assessment and rehabilitation, they can continue to provide health and rehabilitation services, and they can protect children, their families, and medical and rehabilitation staff from transmission [1, 19].

A study in China found that the two most commonly reported problems among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic were pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression [10]. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress were found in 62.6%, 20.5%, and 36.4% of caregivers of children with special needs in India during COVID-19 pandemic, respectively [13]. Symptoms of depression were found in 26% of mothers of children with CP before the pandemic [21]. The QOL of mothers of children with CP was negatively affected due to the burden of care, fatigue, and physiological symptoms [22, 23].

Dhiman et al. found that the caregiver strain of caregivers of children with special needs significantly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. They asked the caregivers to report their current strain and the strain they experienced 1 month before the pandemic [13].

To our knowledge, our study was the first to evaluate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the QOL and fear of COVID-19 of caregivers of children with CP.

Caregivers of disabled children already face the physical and mental difficulties of having a disabled child [3]. The closure of schools and rehabilitation centers along with concerns that their children may be infected due to the high risk of infection may contribute to the reduced QOL of caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The present study found that the physical QOL of caregivers with a history of COVID-19 infection decreased more than caregivers without a history of COVID-19 infection. This result is due to the fact that some symptoms still persist months after the initial COVID-19 infection [24].

More than half of our caregivers had extreme fear of COVID-19, but the education level of caregivers, age of children, age of caregivers, and GMFS levels of children were not found to be factors affecting caregivers’ COVID-19 fear levels. Furthermore, the caregivers’ fear level of COVID-19 was not found to affect the caregivers’ QOL or their children’s visits to the hospital and status of continuing physiotherapy. Extreme fear of COVID-19 has been found to be related to anxiety, health anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptomatology [18]. Although caregivers of children with CP had generally extreme fear of COVID-19, their fear level of COVID-19 may have mostly been affected by personality characteristics.

This study had some limitations. First, the number of participants was limited because some caregivers could not be accessed by phone and some participants were excluded due to a lack of data. Another limitation of this study was a lack of a reliable and valid questionnaire to evaluate general health and physical status of the children, which can be administered through telemedicine. Thus, general health and physical status of the children were evaluated based on the data provided by the caregivers.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused disruptions in the health and rehabilitation services of children with CP. During this period, the general health, mobility, functional status, communication with the environment, and mood of the children were negatively affected. In addition, due to the pandemic, QOL of caregivers of children with CP decreased. We think that more attention should be given to telerehabilitation and telemedicine services of the clinicians who deal with the children with CP in order to prevent the negative effects of future pandemic periods that require social isolation on these children who need medical service and rehabilitation throughout their lives. Added to that, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will likely to continue; thus, we believe that multi-center studies will be effective in the development of telemedicine and telerehabilitation services.

References

Meireles ALF, de Meireles LCF (2020) Impact of social isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic in patients with pediatric disorders: rehabilitation perspectives from a developing country. Phys Ther 100:1910–1912. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzaa152

World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/ (accessed 15th January 2021)

Cacioppo M, Bouvier S, Bailly R et al (2020) Emerging health challenges for children with physical disabilities and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic: The ECHO French survey. Ann Phys Rehabil Med S1877–0657(20):30157–30163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2020.08.001

Öğütlü H (2020) Turkey’s response to COVID-19 in terms of mental health. Ir J Psychol Med 37:222–225. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.57

Demirbilek Y, Pehlivantürk G, Özgüler ZÖ et al (2020) COVID-19 outbreak control, example of ministry of health of Turkey. Turk J Med Sci 50:489–494. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-2004-187

Koman LA, Smith BP, Shilt JS (2004) Cerebral palsy. Lancet 363:1619–1631. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16207-7

Carda S, Invernizzi M, Bavikatte G et al (2020) COVID-19 pandemic. What should Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine specialists do? A clinician’s perspective. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 56:515–524. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06317-0

Yilmaz YalÇinkaya E, KaradaĞ Saygi NE, ÖzyemİŞcİ TaŞkiran Ö et al (2020) Consensus recommendations for botulinum toxin injections in the spasticity management of children with cerebral palsy during COVID-19 outbreak. Turk J Med Sci. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-2009-5

Bertamino M, Cornaglia S, Zanetti A et al (2020) Impact on rehabilitation programs during COVID-19 containment for children with pediatric and perinatal stroke. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 56:692–694. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06407-2

Ping W, Zheng J, Niu X et al (2020) Evaluation of health-related quality of life using EQ-5D in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 15:e0234850. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234850

Tseng MH, Chen KL, Shieh JY et al (2016) Child characteristics, caregiver characteristics, and environmental factors affecting the quality of life of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil 38:2374–2382. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1129451

Gloster AT, Lamnisos D, Lubenko J et al (2020) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: an international study. PLoS ONE 15:e0244809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244809 (PMID: 3338)

Dhiman S, Sahu PK, Reed WR et al (2020) Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on mental health and perceived strain among caregivers tending children with special needs. Res Dev Disabil 107:103790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103790

Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V et al (2020) The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addict 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00270

Doshi D, Karunakar P, Sukhabogi JR et al (2020) Assessing coronavirus fear in indian population using the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. Int J Ment Health Addict 28:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00332-x

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34(3):220–233. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003

Satici B, Gocet-Tekin E, Deniz ME et al (2020) Adaptation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale: its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. Int J Ment Health Addict 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00294-0

Nikopoulou VA, Holeva V, Parlapani E et al (2020) Mental health screening for COVID-19: a proposed cutoff score for the greek version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S). Int J Ment Health Addict 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00414-w

Ben-Pazi H, Beni-Adani L, Lamdan R (2020) Accelerating telemedicine for cerebral palsy during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Front Neurol 11:746. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00746

Wang G, Zhang Y, Zhao J et al (2020) Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet 395:945–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X

Sajedi F, Alizad V, Malekkhosravi G et al (2010) Depression in mothers of children with cerebral palsy and its relation to severity and type of cerebral palsy. Acta Med Iran 48:250–254

Farajzadeh A, Maroufizadeh S, Amini M (2020) Factors associated with quality of life among mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Int J Nurs Pract 26(3):e12811. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12811

Yığman F, Aykın Yığman Z, Ünlü Akyüz E (2020) Investigation of the relationship between disease severity, caregiver burden and emotional expression in caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Ir J Med Sci 189:1413–1419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-020-02214-6

Garrigues E, Janvier P, Kherabi Y et al (2020) Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect 81:e4–e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.029

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our all children and their caregivers for accepting to participate to our study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the University of Health Sciences, Local Institutional Ethics Committee (approval number 105/04).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cankurtaran, D., Tezel, N., Yildiz, S.Y. et al. Evaluation of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with cerebral palsy, caregivers’ quality of life, and caregivers' fear of COVID-19 with telemedicine. Ir J Med Sci 190, 1473–1480 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02622-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02622-2