Abstract

Background

Philadelphia and its suburbs were an epicenter for the initial COVID-19 outbreak. Accordingly, alterations were made in breast cancer care at a community hospital.

Methods

The authors developed a prospective database of all the patients with invasive or in situ breast cancer between March 1 and June 15 at their breast center. Any change in a breast cancer plan due to the pandemic was documented, and the patients were grouped into two cohorts according to whether a change was made (CTX) or no change was made (NC) in their care. The patients were asked a series of questions about their care, including those in the Generalized Anxiety Disorder two-item questionnaire (GAD-2), via telephone.

Results

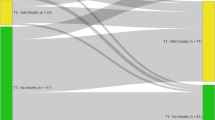

The study enrolled 73 patients: 41 NC patients (56%) and 32 CTX patients (44%). The two cohorts did not differ in terms of age, race, or stage. Changes included delay in therapy (15.1%) and use of neoadjuvant endocrine therapy (NET, 28.8%). The median time to surgery was 24 days (interequartile range [IQR], 16–45 days) for the NC patients and 82 day s (IQR, 52–98 days) for the CTX patients (p ≤ 0.001). The median duration of NET was 78 days. The GAD-2 showed anxiety positivity to be 29.6% for the CTX patients and 32.4% for the NC patients (p = 1.00). More than half (55.6%) of the CTX patients believed COVID-19 affected their treatment outlook compared with 25.7% of the NC patients (p = 0.021).

Conclusions

A prospective database captured changes in breast cancer care at a community academic breast center during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. 44% of patients experienced a change in breast cancer care due to COVID-19. The same level of anxiety and depression was seen in both change in therapy (CTX) and no change (NC). 55.6% of CTX cohort believed COVID-19 affected their treatment outlook.

Similar content being viewed by others

In late 2019, the rapid spread of a severe respiratory illness was first noted in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China.1 A novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), was identified, and the World Health Organization (WHO) termed the illness it caused COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019).2 The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the United States was in January 2020,3 and by March 2020, the virus was categorized as a pandemic.1

By the beginning of March, restrictions had been put in place nationally, dependent on state and county case counts, to decrease transmission of the virus and the disease burden on health systems. In Pennsylvania, an official State of Emergency was enacted on 6 March 2020 mandating business closures and a statewide stay-at-home order. By 19 March 2020, “elective procedures” in Pennsylvania hospitals and ambulatory settings were prohibited.4,5 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid and the American College of Surgeons (ACS) released recommendations to help categorize time-sensitive versus elective procedures with the goal of addressing emergent patient needs while conserving resources and decreasing exposure to COVID-19.6,7

Specialty organizations developed recommendations for the triage of patients during the pandemic. For breast cancer, on 30 March 2020, the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) issued “Resource for Management Options of Breast Cancer During COVID-19,” which gave treatment recommendations based on diagnosis.8 The SSO recommended deferring any consultations and surgeries at least 3 months for atypia, prophylactic/risk-reducing surgery, and benign breast disease. The SSO advocated for genomic testing on the core biopsy specimen for early-stage hormone receptor (HR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative cancers to determine the potential benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus endocrine therapy while delaying surgery for 2–5 months.

Before the pandemic, most centers obtained genomic testing on the final specimen. The COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium published recommendations on priority categorizations for surgical, medical, and radiation oncology based on patient and tumor characteristics (Table 1).9 This multidisciplinary approach considered both the severity of an individual patient’s condition (including patient comorbidities) and the potential efficacy of treatments.8,9

As of 27 July 2020, 111,773 cases of COVID-19 had been confirmed and 6389 deaths had been attributed to COVID-19 in Pennsylvania, with Philadelphia and its suburbs accounting for 42.1% of the cases and 29.3% of the deaths.10 The Main Line Health System (MLHS), a health system of four acute-care hospitals serving Philadelphia and its suburbs, began to see a surge of patients with COVID-19 in March 2020. To conserve resources and ensure patient and provider safety, the health system adopted the national recommendations changing the delivery of breast cancer care. Surgical cases were limited to essential cases, with all non-emergent surgeries cancelled or postponed. Established patients were seen via telemedicine to assess for progression of disease.

On 27 April 2020, the Department of Health announced that hospitals and ambulatory surgical facilities could resume elective surgeries under the condition that doing so would not “jeopardize the safety of patients and staff or the hospital or facility's ability to respond to the COVID-19 emergency.”11 The MLHS resumed elective procedures on 18 May 2020, with the stipulation that all patients must test negative for COVID-19 1–4 days before surgery. Notably, the MLHS is a community health system providing multi-disciplinary breast cancer care in Pennsylvania. Because more than 75% of the surgical care for breast cancer in the United States is delivered in community hospitals, the experience of the impact that COVID-19 has on breast cancer care at our institution reflects the majority of breast cancer care across the nation.12,13

This study aimed to capture the changes made in the multidisciplinary care of breast cancer patients in a community hospital during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study also sought to assess whether these changes were associated with negative reactions from patients related to their overall mental health, breast cancer care, and outlook.

Methods

Setting, Patient Population, and Data Collection

Our health system is composed of four acute-care hospitals located in suburban Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The two acute-care hospitals included in this study are a 331-bed tertiary-care teaching hospital and a 287-bed acute-care teaching hospital located approximately 4 miles from each other. Each hospital has a dedicated breast center, breast surgeons, and a team of medical and radiation oncologists.

As of 15 June 2020, Pennsylvania, the fifth largest state, recorded the 7th largest number of SARS-CoV2 infections in the nation, the 17th largest number of infections per capita, and the 10th largest number of per capita deaths attributed to COVID-19.5 Philadelphia and its surrounding counties were the epicenter of COVID-19 in Pennsylvania.

After Institutional Review Board approval, we developed a prospective database of breast cancer patients during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The inclusion criteria specified patients who had a scheduled surgery date or presented for evaluation between March 1 and June 15 at two comprehensive breast centers in our health system. The exclusion criteria ruled out patients who had a follow-up visit for a surgical intervention before March 1. The patients were contacted via phone call with a survey after presentation to the breast center and before surgical intervention.

Each patient was presented at our multi-disciplinary tumor board and given a surgical prioritization according to national guidelines (Table 1).8,9 The priority A patients required urgent treatment that should not be delayed. The priority B patients were heterogeneous, and decisions related to delay in therapy, alternate therapy, or proceeding with standard therapy were dependent on hospital resources. The priority C patients could be postponed until the end of the pandemic. Guidelines also advocated for the use of neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for patients with HR-positive, HER2-negative tumors to compensate for delays in upfront surgery.

The patients were assigned a multi-disciplinary breast cancer plan in the absence of COVID-19 and as secondary to COVID-19. Any deviations from pre-COVID-19 standards were documented. Based on this information, the patients were placed into one of two cohorts according to their recommended breast care during the pandemic: either a change in recommended treatment (CTX) or no change in recommended treatment (NC).

The breast surgical oncologist, medical oncologist, and radiation oncologist for each patient were asked survey questions at the tumor board discussion including the use of telemedicine and whether the patient was informed of any changes in care due to COVID-19. The use of telemedicine was defined as any documented use of telemedicine services during a patient’s pre- or postoperative course by any provider on the breast cancer team.

Tumor Staging and Pathology

The clinical and pathologic stage was determined based on American Joint Committee on Cancer criteria at the time of diagnosis. Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) were considered negative if immunohistochemistry indicated tumor cell staining of less than 1%. The HER2 status was considered negative if non-amplified by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or if it was 0 or 1+ on immunohistochemistry.

Clinical Parameters

We recorded clinical parameters including age at diagnosis, race, surgical prioritization, pathology, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, pathologic stage, surgery type, presence of COVID-19 testing, use of telemedicine, and time from diagnosis to surgery. As of March 1, COVID-19 testing was implemented only for symptomatic patients and those who had a known COVID-19 exposure. As of May 1, due to increased testing capabilities across the health system, all patients were routinely tested for COVID-19 4 days before planned surgery or at the time of any inpatient admission.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome variable, time to surgery, was calculated as days from diagnosis to definitive surgical intervention. Additionally, duration of neoadjuvant endocrine therapy (NET) in days was calculated if applicable. For the patients who had a delay, the days from the initial planned surgery to the actual definitive surgery were recorded. The setting of surgical dates by the institution was continued throughout the pandemic which, allowed us to track surgical delays.

The secondary outcome variables, obtained through patient phone surveys, included whether the patients identified a change in their breast care due to the pandemic and whether COVID-19 affected their outlook regarding their breast care. The patients also were queried with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder two-item (GAD-2) questionnaire, a screening tool for generalized anxiety disorder. The GAD-2 uses two Likert-type questions, and the scores from the two questions are summed for each patient to form a total score between 0 and 6. Total scores of 3 or higher have been validated as a cutoff to indicate clinically significant anxiety symptoms (GAD-2 anxiety positivity).14

Concordance between actual and perceived treatment was a secondary outcome. The patients were categorized as concordant if they either had a change in treatment or could identify the change in the patient phone survey or they had no change in treatment and were able to respond as such.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation if normally distributed or median (interquartile range [IQR]) if non-normally distributed. Categorical variables are presented as frequency (percentage). Normality was assessed for continuous variables using histograms, descriptive statistics, and the Shapiro–Wilk test.

Clinical characteristics, demographics, and survey responses were compared between the CTX and NC groups using two-sample t tests (for normally distributed continuous variables), the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for non-normally distributed continuous variables), and Fisher’s exact tests (for categorical variables). Similar comparisons were made between the patients given NET versus those who experienced a delay in surgical date only, but comparisons were performed only descriptively due to the small group sample sizes.

Univariate logistic regression models were built to test associations between clinical and patient characteristics and the following two outcomes: change in treatment and GAD-2 anxiety positivity. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented from the models. Multivariable models were considered but ultimately not built because surgical prioritization was the only independent variable with a p value lower than 0.20 for both outcomes.

All data were analyzed using Stata/MP 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All tests were two-sided, and the significance level was 0.05.

Results

Of the 73 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 41 (56%) experienced no change in treatment and 32 (44%) experienced a change in treatment (Table 2). There NC and CTX cohorts did not differ in average age at breast cancer diagnosis (60.6 ± 13.5 vs. 60.6 ± 13.1 years; p = 0.996), race (80.5% vs. 87.5% Caucasian; p = 0.856), pathologic stage (41.7% vs. 45.8% stage 1; p = 0.800) or use of telemedicine (85.4% vs. 90.6%; p = 0.722). Hormone status on core biopsy differed between the NC and CTX cohorts as follows: hormone receptor positivity (65.9% vs. 75%; p < 0.001), HER2 positivity (9.8% vs. 0%; p < 0.001), and triple negativity (22% vs. 0%; p < 0.001). Among the CTX cohort, 59.4% given NET compared with only 2.4% of the NC cohort (p < 0.001).

All the patients who experienced a change in their breast cancer treatment were informed of the change. Among the 32 patients who experienced a change in treatment, 21 (65.6%) given NET, and 11 (34.4%) experienced a delay in surgery date alone (Table 3). The NET and delay-only groups were similar in terms of average age at diagnosis (59.7 ± 12.6 vs. 62.3 ± 14.4 years) and telemedicine use (90.5% vs. 90.9%). The NET group was more likely to be Caucasian (90.5% vs. 81.8%), have a higher surgical prioritization (81% vs. 54.6% B3), and have a slightly higher pathologic stage (18.8% vs. 12.5% stage 2 or 3 disease). Only 31.6% of the NET group had a partial mastectomy compared with 70% of the delay-only group. A majority (57.1%) of the NET group had invasive ductal carcinoma compared with 36.4% of the delay group. The days between breast cancer diagnosis and surgery are summarized in Table 4.

Patients were excluded if they had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (13 NC, 1 CTX), had their surgery at another institution (1 CTX), decided against surgery (1 NC, 1 CTX, or chose to delay surgery (1 CTX). The median time to surgery from breast cancer diagnosis was 24 days (IQR, 16–45 days) in the NC cohort and 82 days (IQR, 52–98 days) in the CTX cohort (p ≤ 0.001; Table 4).

Those who experienced a delay in surgical date alone had a median time to surgery of 70.5 days (IQR, 42–89 days). However, those receiving NET had a longer median time to surgery of 85 days (IQR, 54–100 days; p = 0.240). The median duration of NET was 78 days (IQR, 47–93 days). The NC cohort showed no difference in time between the planned and actual surgical date (median, 0; IQR, 0–0). The CTX cohort had a median delay of 50.5 days (IQR, 37–63 days). More specifically, the treatment cohort had a delay of 45.5 days (IQR, 36–68 days) compared with a delay of 52 days (IQR, 40–63 days) for those receiving NET (p = 0.981).

The NC and CTX cohorts did not differ in terms of GAD-2 anxiety positivity (32.4% vs. 29.6%; p = 1.000; Table 5). A change in breast cancer care was recognized by76.9% of the CTX cohort, although the providers reported that 100% of the CTX cohort was informed. Despite no alterations in care, 11.4% of the NC cohort reported that a change in their breast cancer care had occurred. The overall concordance rate in the total cohort was 83.6%. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, 47.8% of the CTX cohort were concerned about alterations made in their breast cancer care. The CTX cohort was significantly more likely than the NC cohort to report that COVID-19 was affecting their outlook of their breast care (55.6 % vs. 25.7%; p = 0.021) despite similar distributions of GAD-2 scores.

In the univariate logistic regression models, age, race, and histology from core biopsy were not significantly associated with a change in treatment (Table 6). Surgical prioritization was the only variable significantly associated with a change in treatment (p = 0.048). Specifically, the patients in the B3 priority group (OR, 8.01; 95% CI 1.12–infinity; p = 0.037) and those in the C1/C2 priority group (OR, 9.08; 95% CI 1.12–infinity; p = 0.037) were significantly more likely to have a change in treatment than the patients in the B1/B2 group. Change in treatment did not differ significantly between the B3 and C1/C2 prioritizations (p = 0.884). No variables were significantly associated with GAD-2 anxiety positivity, but, as the level of surgical prioritization decreased, so did the rate of GAD-2 anxiety positivity. Specifically, the GAD-2 anxiety positivity rates were 60%, 34.2% and 13.3% in the B1/B2, B3 and C1/C2 prioritization groups, respectively.

Discussion

A cancer diagnosis is a very stressful time in an individual's life. Experiencing a new cancer diagnosis amid a pandemic presents a new set of stressful life events. With an unprecedented delay in elective surgical procedures affecting many of our breast cancer patients, our health care system provides a unique view into changes experienced at a community academic breast center. Using surveys, we captured patients’ perceptions of changes in breast cancer treatment. This study provides insight into COVID-related changes in breast cancer care to help inform potential future interruptions to health care delivery.

In response to COVID-19, we evaluated changes in breast cancer treatment at our institution in accordance with national recommendations and prioritization.8,9 The two changes observed in a prospective fashion were a delay in surgical date and a delay in surgical date with the use of NET. All changes were recorded. Delay and use of NET were the only two changes observed across our health system. We anticipated changes in breast reconstruction, but this was not observed in our institutional experience. Whereas NET for HR-positive breast cancer is commonly used in Europe, it was not used routinely in the United States before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Spring et al.15 performed a meta-analysis regarding NET for ER-positive breast cancer. Their study found that NET provided similar rates of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with less toxicity. Although positive results have been observed internationally, COVID-19 will provide insight into the expanded use of NET for HR-positive breast cancer, as seen in our cohort of patients.

About 30% of breast cancer patients report positive GAD-2 scores after a breast cancer diagnosis.16 Our patients reported similar GAD-2 scores, with 32.4% scoring positive in the NC cohort and 29.6% scoring positive in the CTX cohort. We anticipated a higher percentage of positive GAD-2 scores in our cohort due to the pandemic, but this was not observed in comparison with prior studies.17 We anticipated that patients who had a change in their breast cancer care would express higher levels of anxiety or depression, but this also was not observed. Interestingly both cohorts had similar levels of anxiety despite changes in treatment. Although GAD-2 anxiety positivity did not differ between the two cohorts, the CTX cohort did report that “COVID-19 changed their outlook on their breast cancer care” at a higher percentage than the NC cohort.

Although all the patients who experienced a change in their care were informed, 23.1% of the CTX cohort did not recognize that a change had occurred. This was not a surprising given the reported rates of the patients’ health literacy and understanding of their diagnosis and treatment.18,19 Fagerlin et al. had similar findings. In their study, 16% of the women knew mastectomy had a lower recurrence risk than breast-conserving surgery, and 48% of women knew that the survival benefits were equivalent. Although we hypothesized that patients who experienced changes in their care would have higher GAD-2 scores than those who had no changes in care, the GAD-2 anxiety positivity rates in our study were 29.6% for the CTX cohort and 32.4% for the NC cohort. This may be explained by the fact that the patients who had a change in care did not register this as a true change. This further demonstrates the necessity for better communication and patient education so that shared decision-making can become a reality.

The time to treatment differed between the CTX and NC cohorts. The patients in the CTX cohort had a median time to treatment of 82 days (IQR, 52–98 days), significantly longer than the median of 24 days (IQR, 16–45 days) in the NC cohort. However, the time to surgery for the CTX cohort was equivalent to the non-COVID time to surgery nationally, which can be up to 90 days.21 Because all these changes were implemented in a community hospital during the COVD-19 pandemic in response to national guidelines, the changes, delays, and perceptions of care are representative of the national landscape. Currently, more than 75% of breast cancer care is delivered in community hospitals, and it thus is important that this study capture this model of care.12,13

A limitation of this study was the small sample in each cohort (41 NC patients, 32 CTX patients). Small sample sizes can lead to insufficient power, thus increasing the likelihood of type 2 errors. Therefore, nonsignificant results should be interpreted with caution, and larger, well-powered prospective studies are necessary for further evaluation of the relationship between changes in breast cancer treatment and time to surgery as well as patient anxiety, depression, and overall outlook during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the sample was small, a majority of breast cancer care was performed in a community academic breast center. Our results are representative of the national experience for breast cancer care.

In conclusion, in a COVID-19 epicenter, breast cancer care was altered accurding to national recommendations for approximately half of the patients.8,9 The two alterations observed were a delay in surgical date and a delay in surgical date with NET. Although CTX did not alter a patient’s level of anxiety or depression, it did affect the patient’s overall outlook. This experience in a community academic breast cancer center provides insight for future disruptions in health care delivery.

References

WHO Timeline–COVID-19. 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020 at https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline-covid-19.

WHO Director-General’s remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. Retrieved5 June 2020 at https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020.

Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929–36.

PA Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update Archive. Retrieved 24 July 2020 at https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/disease/coronavirus/Pages/Archives.aspx.

State Guidance on Elective Surgeries–Ambulatory Surgery Center Association (ASCA). 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020 at https://www.ascassociation.org/asca/resourcecenter/latestnewsresourcecenter/covid-19/covid-19-state.

CMS. CMS releases recommendations on adult elective surgeries, non-essential medical, surgical, and dental procedures during COVID-19 response | CMS. Retrieved 24 July 2020 at https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-releases-recommendations-adult-elective-surgeries-non-essential-medical-surgical-and-dental.

COVID-19: Guidance for triage of non-emergent surgical procedures. Retrieved 24 July 2020 at https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/triage.

Society of Surgical Oncology. Resource for management options of breast cancer during COVID-19. 2020.

Dietz JR, Moran MS, Isakoff SJ, et al. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment, and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. the COVID-19 pandemic breast cancer consortium. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;181(3):487–497.

Times NY. Coronavirus in the U.S.: latest map and case count. The New York Times, 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020 at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html#states.

Guidance on Hospitals’ Responses to COVID-19. Retrieved 26 July 2020 at https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/disease/coronavirus/Pages/Guidance/Hospital-Guidance.aspx.

Dodgion CM, Lipsitz SR, Decker MR, et al. Institutional variation in surgical care for early-stage breast cancer at community hospitals. J Surg Res. 2017;211:196–205.

Spain P, Teixeira-Poit S, Halpern MT, et al. The national cancer institute community cancer centers program (NCCCP): sustaining quality and reducing disparities in guideline-concordant breast and colon cancer care. Oncologist. 2017;22:910–7.

Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, et al. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24–31.

Spring LM, Gupta A, Reynolds KL, et al. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1477–86.

Tsaras K, Papathanasiou IV, Mitsi D, et al. Assessment of depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients: prevalence and associated factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:1661–9.

Fradelos EC, Papathanasiou IV, Veneti A, et al. Psychological distress and resilience in women diagnosed with breast cancer in Greece. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:2545–50.

Freedman RA, Kouri EM, West DW, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in knowledge about one’s breast cancer characteristics. Cancer. 2015;121:724–32.

Bickell NA, Weidmann J, Fei K, et al. Underuse of breast cancer adjuvant treatment: patient knowledge, beliefs, and medical mistrust. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5160–7.

Fagerlin A, Lakhani I, Lantz PM, et al. An informed decision? Breast cancer patients and their knowledge about treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:303–12.

Solomon M, Cochrane CT, Grieve DA. Insurance status and time to completion of surgery for breast cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86:84–7.

Acknowledgement

We thank the breast cancer team at Lankenau and Bryn Mawr for their hard work and dedication to this project, especially Lauryn McGeever, Mary Beth Merola, Dr. Jennifer Sabol, and Dr. Robin Ciocca.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kennard, K., Williams, A.D., Goldblatt, L.G. et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: Changes in Care for a Community Academic Breast Center and Patient Perception of Those Changes. Ann Surg Oncol 28, 5071–5081 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09583-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09583-3