Abstract

Background

The psychological effects from the COVID-19 pandemic and response are poorly understood.

Objective

To understand the effects of the pandemic and response on anxiety and health utility in a nationally representative sample of US adults.

Design

A de-identified, cross-sectional survey was administered at the end of April 2020. Probability weights were assigned using estimates from the 2018 American Community Survey and Integrated Public Use Microdata Series Estimates.

Participants

US adults 18–85 years of age with landline, texting-enabled cellphone, or internet access.

Intervention

Seven split-half survey blocks of 30 questions, assessing demographics, COVID-19-related health attitudes, and standardized measures of generalized self-efficacy, anxiety, depression, personality, and generic health utility.

Main Measures

State/Trait anxiety scores, EQ-5D-3L Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score, and demographic predictors of these scores.

Key Results

Among 4855 respondents, 56.7% checked COVID-19-related news several times daily, and 84.4% at least once daily. Only 65.7% desired SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for themselves, and 70.1% for their child. Mean state anxiety (S-anxiety) score was significantly higher than mean trait anxiety (T-anxiety) score (44.9, 95%CI 43.5–46.3 vs. 41.6, 95%CI 38.7–44.5; p = 0.03), with both scores significantly higher than previously published norms. In an adjusted regression model, less frequent news viewing was associated with significantly lower S-anxiety score. Mean EQ-5D-3L VAS score for the population was significantly lower vs. established US normative data (71.4 CI 67.4–75.5, std. error 2 vs. societal mean 80, std. error 0.1; p < 0.001). EQ-5D-3L VAS score was bimodal (highest with hourly and no viewing) and significantly reduced with less media viewership in an adjusted model.

Conclusions

Among a nationally representative sample, there were higher S-anxiety and lower EQ-5D-3L VAS scores compared to non-pandemic normative data, indicative of a potential detrimental acute effect of the pandemic. More frequent daily media viewership was significantly associated with higher S-anxiety but also predictive of higher health utility, as measured by EQ-5D-3L VAS scores.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

In late 2019, the SARS-CoV-2 virus and resulting COVID-19 disease emerged as a pandemic threat, spreading from China across Asia, Europe, North America, and South America over the first few months of 2020.1, 2 By early November 2020, worldwide cases have exceeded 54,000,000 and COVID-19-related fatalities have surpassed 1,300,000, including 11,000,000 cases and 246,000 fatalities in the USA.3 By late March 2020, the majority of the USA was under state/local “shelter in place” orders to limit further viral spread among individuals, and reduce potential capacity overload within healthcare systems. Many businesses and services also temporarily shut down or reduced capacity. This response was not unique to the USA.4 This pandemic has become a major defining event of 2020, and possibly a major international historical event. Even in late 2020, 8–10 months after the pandemic emerged, many countries continue to struggle to implement public health measures to contain and mitigate viral spread, and are again implementing shelter-in-place orders, closing/reducing capacity of businesses including medical practices, and continued physical distancing measures and mandates for wearing masks in public.4 Much of the US population has experienced some degree of prolonged home confinement (except for essential functions), followed by relaxation of those standards, and cycles where such options re-emerge for consideration based on community case rates. As a result, these circumstances could be associated with significant potential psychosocial stress, and “pandemic fatigue” among the public.5, 6

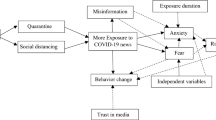

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized the negative potential that the pandemic could have on society, and early on highlighted an acute need for research into mental health issues to understand how individuals may respond.7 For many Americans, shelter-in-place orders, job furlough/loss, and/or forced remote work created unique and unprecedented circumstances not experienced in prior epidemics/pandemics, and compounded by a 24-h social media and news cycle. Research into the impact of previous pandemics on the general public, patients, and healthcare workers has noted an impact on worsening state anxiety (S-anxiety), increased psychiatric morbidity, and other facets of mental health such as anger and pessimism.8,9,10,11,12,13,14 However, the COVID-19 pandemic brings unique circumstances of enhanced information dissemination (including news) via social media, combined with politicization of opinion and response, and variability in adherence with/acceptance of recommendations that has not been previously experienced. A 2018 Pew Research Center study suggests that 2/3 of US adults may at least occasionally get their news from social media.15 The WHO has labeled this unique set of circumstances an “infodemic,” referring to the “flood of information regarding the COVID-19 pandemic,” coming from the government, scientists, the media, social media/internet, and friends/family, where what is fact, opinion, or credible is harder to discern as is the perception of what is actual and perceived risk.16,17,18 As evidence for this potential danger, a recent Russian COVID-related survey noted an association between increased media consumption and higher S-anxiety levels.19

To better understand the potential influence of these unique factors on the pandemic, the purpose of our study was to determine if there are any cross-sectional relationships between news media consumption and standardized survey-based indicators of mental health status such as state/trait anxiety, depression, and general health state utility among the US population. As well, we sought to assess potential attitudes towards pandemic responses and precautions at a population level. We hypothesized that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and response has increased anxiety and depression, and worsened generalized health utility, as measured through a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey timed to coincide with the end of the initial shelter-in-place orders in most states.

METHODS

Survey Items

In conjunction with Emerson College Polling, investigators developed a 130-item ad hoc cross-sectional survey, administered to adult participants ages 18–85 years in late April 2020 as part of an international effort to understand the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general population.20 Items consisted of questions about COVID-19, demographics, extent/duration of media viewership, medical comorbidities, and health status. Additionally, ad hoc questions on a 9-point Likert scale (ascending level of agreement) queried general pandemic attitudes towards preparedness, protective measures, infection/infection-control risk, COVID-19 disease impact, testing/treatment/vaccination attitudes, and employment. Lastly, 3 short-form standardized psychosocial health indices were administered—the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, short form), Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) depression/anxiety short scale, and the EQ-5D-3L health utility index. Index psychometric properties are detailed in Table 1.21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 To reduce survey fatigue and increase response likelihood, the items were split into 7 overlapping 30-item blocks for random administration to distinct samples. Item generation and selection occurred in late March 2020. The main outcomes included EQ-5D-3L visual analog score (VAS), the PHQ-4 score, the STAI domain scores, and the mean scores of the ad hoc questions. The survey items were administered in English only.

Sampling Methodology

Participants were recruited for de-identified survey data collection using a combined methodology of (a) landlines for interactive voice response; (b) text message data collection using Aristotle Inc.; and (c) online panels provided by Dynata and Amazon Mturk. Emerson College Polling was responsible for conducting/administering the survey blocks. Data were collected between April 25 and May 6, 2020. Electronic or verbal-assisted informed consent was obtained for “opt-in” participation. A set of 14 pre-specified demographic background questions for stratification purposes were administered with each block and served as covariates (eTable 1). Question blocks did not otherwise overlap. Each sample used a combination of probability and non-probability sampling methods, and a Bayesian Credibility Interval (BCI) similar to a poll’s margin of error (MOE) was calculated for each individual block. Data were assigned probability weights using parameters taken from 2018 American Community Survey estimates of gender, age range, marital status, educational attainment, and household income for Americans over the age of 18. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series Estimates from the US Census were also used for the number of children under 18 years of age per household, race, ethnicity and employment status30. See eTable 2 for further details of the survey methodology, including strata contact/response rate and MOE of reporting. Inclusion criteria included age 18–85 years; and owning either a landline, cellphone with texting capabilities, or computer with available internet connection to access the survey.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata SE, version 15. Stata survey mode was used with seven sampling stratum and probability weights assigned with each strata obtaining a minimum subset of 10% of the sample size to be weighted. There were no missing data, given only complete responses were included in the final data set. Data were analyzed for descriptive statistics and measures of central tendency, with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) reported. Wald tests, Fisher exact text, Spearman correlation, and linear, logistic, and ordinal regression with the margins post-estimation command were used for inferential analysis. Regression models used the common demographic items across all survey blocks as pre-specified independent variables. Taylor linearized standard errors were reported. p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for all analyses. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institution Review Board as exempt from ongoing review.

RESULTS

A total of 4855 participants responded to the seven survey blocks, for an average of 607 participants per block (range 523–706, eTable 1). Table 2 details the sample weighted demographics. Among the respondents, 75% reported they were in self-isolation and 76% that their faimily were in self isolation (no significant association with any demographic trend), and reported being outside of their homes a mean of 2.32 days (CI 2.35–3.31) in the week prior to survey response. COVID-related news viewership was high, with 56.7% checking for updates at least several times per day, and 84.4% at least once daily. The ordered log odds of checking news more frequently was associated with older age (50–59 years coef. 0.73, CI 0.21–1.25, p = 0.005; 60–69 years coef. 0.78 CI 0.25–1.31, p = 0.004; and > 70 years 1.14, CI 0.56–1.7, p < 0.001) and male sex (coef. 0.37, CI 0.12–0.62, p = 0.004) (model significance p < 0.001) but no other pre-specified covariates.

Pandemic/Pandemic Response Effect on S-/T-Anxiety and Depression

Mean S-anxiety score across all ages was significantly higher than T-anxiety score (44.9 [CI 43.5–46.3] vs. 41.6 [CI 38.7–44.5], p = 0.03). S-anxiety scores were higher in females than males (46.3 [CI 44–48.8] vs. 43.4 [CI 42.1–44.8], p = 0.03; NS for T-anxiety). S-anxiety scores were higher in the oldest age tier (age > 70) vs. other age tiers (p = 0.01). All subpopulations in the surveyed block for STAI had significantly higher S-anxiety and T-anxiety scores than published age norms, with mean differences ranging from 6 to 10 scale points (p < 0.001).

In an adjusted multiple linear regression assessing predictors of S-anxiety score (Table 3 A), S-anxiety score was significantly lower for “more than once daily” and “once daily” news viewing vs. more frequent viewing. However, for T-anxiety (Table 3 B), while the effect of “no news viewing” was noted, higher income (p = 0.004) and older age (25–29 years and > 70 years, vs. 18–24 years) was associated with significantly lower T-anxiety scores. No significant effects were observed in either model for education or geography. A dominance analysis (not shown) noted that either S- or T-anxiety score was the predominant predictor variable in the regression models for one another, respectively, followed by news viewership and healthcare worker status (state model), and savings followed by news viewership (trait model). In hierarchical analyses of these models, for S-anxiety, only adding news viewership, T-anxiety, and healthcare worker status to the models offered significant improvement (15.8%, 0.8%, and 0.9% variance explained). For T-anxiety, adding news viewership, state anxiety, age, gender, income, and savings offered significant improvement (15.7%, 1%, 0.9%, 1.9%, 4.9% of variance explained; data not shown).

For depression, mean total PHQ score was 3.2 (CI 2.6–3.7), with mean anxiety and depression domain scores each of 1.6 (CI 1.3–1.8), respectively, below the screening cutoff for either clinical anxiety or depression. Total PHQ score and either the individual anxiety or depression PHQ subdomain scores were significantly associated with increased S- and T-anxiety scores in univariate and adjusted models (eTable 3a–d). No significant relationship was noted between news viewership and either total PHQ score or either PHQ sub-domains.

Pandemic/Pandemic Response Effect on General Health State Utility

Mean EQ-5D-3L VAS score for the surveyed population was 71.4 (CI 67.4–75.5, std. error 2) and significantly lower than the mean normative population total score (societal mean score 80, std. error 0.1) and age-tier scores (Fig. 1a).27, 31 No significant sex-based differences were noted. For the 5 dimensions measured in the EQ-5D-3L, 11.1% indicated issues (e.g., level 2 or 3 response for the item on a 1–3 point scale) with mobility, 7.2% with self-care, 16.1% with usual activities, 44% with pain/discomfort, and 49.4% with anxiety/depression issues. These were significantly different from population norms for mobility (lower, 11% vs 18.5%, p < 0.001), self-care (higher, 7.2% vs 3.2%, p < 0.001), and anxiety (higher, 49.4% vs 23.2%, p < 0.001). In the same demographic adjusted regression model used for STAI score, EQ-5D-3L VAS score was bimodal and highest with either hourly or no media viewing. VAS score was significantly lower with lower media viewership (more than once daily, daily, and more than once weekly vs. hourly, NS vs. weekly and no viewing), and not associated with any other demographic predictor (Table 3 C, Fig. 1b).

EQ-5D-3L Visual Analogue Score assessed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Panel a denotes EQ-5D-VAS assessed during the pandemic compared to normative trend by age tier. Asterisks indicate values significantly lower (worse) VAS than normative data (p < 0.001). Panel b denotes a bimodal relationship between quantity of time per week spent viewing news stories regarding COVID-19 and the predicted EQ-5D-VAS value. Asterisks indicate values significantly lower (e.g., worse) VAS than baseline (p < 0.05) associated with viewing news multiple times a day, daily, and multiple times a week vs. hourly viewing.

Cognitive Attitudes Regarding the Pandemic/Pandemic Response

Lastly, given the uniqueness of the pandemic response, we queried (1) attitudes towards preparedness measures, (2) agreement with pandemic response measures, and (3) self-perceived infection and infection-control risk from a series of ad hoc exploratory items (Fig. 2, panels a–c). Most respondents indicated low to moderate agreement that they would contract COVID-19, and moderate agreement that infection would be symptomatic or severe. Using the same demographic adjusted model (R2 = 0.52, F = 22.5, p < 0.001) for STAI and EQ-5D-3L (eTable 4), increasing level of agreement that one would become infected was significantly (positively) associated with agreement that infection would be symptomatic, that community members were affected, and with increasing level of education, but negatively associated with increasing income tier. Use of masks or gloves as protective measures for self or others was unrelated to underlying perception of infection risk.

Respondent reported health beliefs and attitudes regarding the pandemic and pandemic response. Panels a, b, and c denote reported COVID-19-related health beliefs and attitudes, assessed on a 9-point Likert scale of increasing level of agreement with the statement. Panel a denotes general trends related to preparation with respect to goods/services, panel b trends with respect to COVID infection/infection risk, and panel c trends with respect to the governmental response.

Among those sampled, 55% (n = 694 weighted respondents) reported they believed a vaccine would be available within a year, with 65.7% affirming they desired SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for themselves, and 70.1% for their child. Only 28% of the sample desired testing if they were asymptomatic, and only 54% desired testing after the pandemic ended to see if they had been infected, which was significantly correlated (rho = 0.51, p < 0.001). There were no significant relationships with either testing or vaccination attitudes in regression models using the aforementioned demographic predictors.

DISCUSSION

This survey has attempted to measure aspects of the baseline psychological impact of the pandemic among the US population. We are not aware of any prior US study of associations among anxiety, health state utility, and media viewership. Understanding the relationship between psychological factors and behaviors in global pandemics is key to the development of disease mitigation actions. Beyond the aforementioned Russian sister publication,19 we note only a handful of similar (though distinct) studies from Asia and from Germany exploring COVID-related psychological trends.32, 33

Compared to normative baselines, age-adjusted S-anxiety and T-anxiety was higher (worse) and health utility scores were lower when measured 6 weeks into the pandemic. We found that S-anxiety scores were elevated vs. T-anxiety, another indicator of an acute effect. State anxiety describes the psychological and physiological transient reactions directly related to adverse situations at a specific time, whereas trait anxiety refers to a trait of personality that is to the individual differences in the tendency to become anxious. Thus, the higher the trait anxiety, the higher the state anxiety in situations of threat.25, 34 Whether or not people who differ in T-anxiety will show corresponding differences in S-anxiety depends on the extent to which they perceive a situation as psychologically dangerous or threatening. Individuals with high T-anxiety tend to interpret a wider range of situations as dangerous/threatening, particularly in situations that involve interpersonal relationships, which is central to the COVID-19 psychosocial experience.22 Not all persons with elevated T-anxiety and S-anxiety scores manifest a diagnosed anxiety disorder—PHQ-4 scores for anxiety and depression did not reach the clinical threshold for screening that indicates concern. Our regression models noted that the highest S-anxiety scores were associated with the highest media viewership levels and were lower with decreasing viewership. This may reflect the “infodemic” in late March 2020.35, 36 However, this study was not designed to infer any causality, but rather describe exploratory relationships.

Similarly, mean and age-tier EQ-5D-3L VAS health utility score were significantly lower than population norms. With the exception of the oldest age tiers (2.3%), the absolute mean differences were 15.3–19.4% lower than normative data, reflecting a potentially significant health detriment. This translates to a trade-off of ~ 3 years of life in a 20-year time horizon, or 54 days of life in a single year vs. baseline norms. However, while it is difficult to determine the clinical significance, given no known minimal important difference (MID) index value for a pandemic context (MID is disease and population specific), for contextual comparison of these aforementioned differences, the EQ-5D-3L VAS MID in cancer is 7%.37 Interestingly, health utility had a novel relationship with media viewership compared to S-anxiety—the highest and lowest viewership levels were associated with the highest health utility scores. The reasons for this are not entirely understood, but may be due to an unmeasured variable, or suggest possible subgroups with heterogeneity of media influence. This requires future study. From a theoretical perspective, it is important to note that both minimized and exaggerated perceptions of risk can potentially undermine the adoption of protective health behaviors.38

Importantly, only 2/3 of those surveyed would take a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, and just slightly more than half of the sample was interested in undergoing testing to determine evidence of past infection. There are minimal data regarding pandemic vaccine and testing attitudes, though acceptance of an available vaccine and willingness to undergo testing and/or contact tracing are important steps to a successfully societal response to the pandemic.39 Implementation science emphasizes the benefits of a multidisciplinary perspective and the use of real-world data, and such an approach may boost vaccine acceptability, given achieving herd immunity may be challenging if only 66% of the population is willing to be vaccinated.40,41,42 Mean levels of feeling informed about the pandemic, prevention measures, and healthcare guidance were high, though agreement with the extent of national or local preparedness was moderate, and trust in the federal governmental response still lower. However, there was low agreement that local/national measures taken to stem infection spread were excessive. Self-perception that one would become infected was positively associated with education and negatively associated with income. Concern regarding becoming infected was associated with concerns for symptomatic and potentially severe infection. However, because of the block design, health utility and STAI were not asked in association with concerns for infection, requiring additional study to determine if these variables are associated.

This study has several limitations. First, survey data has potential issues of information validity, responder truthfulness, and selection and reporting bias. Use of weighted, nationally representative data collected using multi-stage sampling method helps mitigate these risks. Second, these data are cross-sectional, and assessed at the end of a period in the pandemic when most Americans were sheltering in place. We were unable to track the longitudinal evolution of these trends during any phase of the pandemic or response. Third, a block design with random selection was used, meaning that not all items were assessed together or by all participants, which limits some of the associations that can be made. We accepted this trade-off to be able to ask a wider range of questions across a nationally representative panel. Fourth, several questions, in particular those regarding health beliefs and precautions, were ad hoc, and we did not ask respondents to elaborate on their sources of information. Fifth, there are few established hypotheses for US behavioral trends in a pandemic, given a unique, highly politicized situation in a social media–influenced environment. This limited the survey as cross-sectional, exploratory in nature, and explains why certain potential trends were not asked together but rather focused primarily on anxiety, depression, and health utility—areas where evidence suggested susceptibility from health-related events. Therefore, we did not attempt to determine or infer causality and instead explored potential associations to better inform future potential pandemic situations. Additional research is warranted to determine if the S-anxiety and health utility trends are associated with the pandemic attitudes, assess stability of the findings as the pandemic progresses, and explore causality. Sixth, and lastly, the survey was only administered in English, and thus the findings may not be representative of non-English-speaking US populations.

This nationally representative survey of the US population indicates that there may be S-anxiety and generic health utility detriments related to the COVID-19 pandemic compared to normative data, indicative of pandemic-related acute health detriment, and possibly driven by media viewership, reinforcing the concept of the “infodemic.” Furthermore, interest in SARS-CoV-2 vaccination is potentially low—a worrisome trend for establishing future herd immunity. These data may help to better frame the potential for psychosocial detriment in response to similar events, including future waves of this pandemic, and the health utility data in particular may help to better valuate the detriment that could be experienced by individuals, and create opportunities to help mitigate any detrimental effects (such as S-anxiety) of a global news cycle regarding such events. Research evaluating the direct and the indirect longer term effects on mental health is needed to improve healthcare planning and for preventive measures during potential subsequent pandemics. Research on the impact of SARS-CoV-1 epidemic in the general public found that those impacted (e.g., by quarantine) had psychiatric symptoms months after control of the epidemic.14 This may suggest long-term effects after SARS-CoV-2 also must be expected.

Abbreviations

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- QALY:

-

Quality of life adjusted years

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus 2019

- VAS:

-

Visual Analog Scale

- S-anxiety:

-

State anxiety

- T-anxiety:

-

Trait anxiety

- BCI:

-

Bayesian Credibility Interval

- MOE:

-

Margin of error

- PHQ-4:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-4 depression/anxiety short scale

- STAI:

-

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

References

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727-33.

Del Rio C, Malani PN. COVID-19-new insights on a rapidly changing epidemic. JAMA 2020;323:1339-40.

Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed 17 Nov 2020.

Gostin LO, Wiley LF. Governmental public health powers during the COVID-19 pandemic: stay-at-home orders, business closures, and travel restrictions. JAMA 2020;323:2137-8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Coping with Stress Accessed June 28, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/managing-stress-anxiety.html

Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:547-60.

Kluge HHP, Malik A, Nitzan D. Mental health and psychological resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/mental-health-and-psychological-resilience-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (Accessed June 28, 2020).

Auerbach J, Miller BF. COVID-19 exposes the cracks in our already fragile mental health system. Am J Public Health 2020;110(7):e1-2. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305699.

Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:228-9.

Blendon RJ, Benson JM, DesRoches CM, Raleigh E, Taylor-Clark K. The public’s response to severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto and the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:925-31.

Cheng C, Cheung MW. Psychological responses to outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome: a prospective, multiple time-point study. J Pers 2005;73:261-85.

Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC, Lee CY, Chiu NM, Yeh WC, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry 2004;185:127-33.

Jeong H, Yim HW, Song YJ, Ki M, Min JA, Cho J, et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiol Health 2016;38:e2016048.

Peng EY, Lee MB, Tsai ST, Yang CC, Morisky DE, Tsai LT, et al. Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: an example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2010;109:524-32.

https://www.journalism.org/2018/09/10/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2018/. Accessed November 3, 2020.

https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/let-s-flatten-the-infodemic-curve. Accessed November 3, 2020.

Wise T, Zbozinek TD, Michelini G, Hagan CC, Mobbs D. Changes in risk perception and self-reported protective behaviour during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. R Soc Open Sci 2020;7:200742.

Dryhurst S, Schneider CR, Kerr J, Freeman ALJ, Recchia G, van der Bles AM, et al. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. Journal of Risk Research 2020:1-13.

Nekliudov NA, Blyuss O, Cheung KY, Petrou L, Genuneit J, Sushentsev N, et al. Excessive media consumption about COVID-19 is associated with increased state anxiety: outcomes of a large online survey in Russia. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e20955.

Nekliudov NA, Blyuss O, Cheung KY, Petrou L, Genuneit J, Sushentsev N, Levadnaya A, Comberiati P, Warner JO, Tudor-Williams G, Teufel M, Greenhawt M, Galvin AD, Munblit D. Excessive media consumption about COVID-19 is associated with increased state anxiety: outcomes of a large online survey in Russia. JMIR Preprints. 02/06/2020:20955. https://doi.org/10.2196/preprints.20955. URL: https://preprints.jmir.org/preprint/20955.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009;50:613-21.

Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory ( rev. ed.). Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psychol 1992;31:301-6.

Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63 Suppl 11:S467-72.

Kvaal K, Ulstein I, Nordhus IH, Engedal K. The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI): the state scale in detecting mental disorders in geriatric patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:629-34.

Rabin R, Gudex C, Selai C, Herdman M. From translation to version management: a history and review of methods for the cultural adaptation of the EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire. Value Health 2014;17:70-6.

Szende A, Janssen B, Cabases J. Self-reported population health: an international perspective based on EQ-5D. Dordrecht: Springer; 2014.

Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001;33:337-43.

van Reenen MO, M. EQ-5D-3L User Guide: Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-3L instrument. Rotterdam: EuroQol Research Foundation; 2015.

Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) Documentation. Accessed June 28, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/pums.html

Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V. Preference-Based EQ-5D index scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Decis Making 2006;26:410-20.

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(5):1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729.

Bauerle A, Teufel M, Musche V, Weismuller B, Kohler H, Hetkamp M, et al. Increased generalized anxiety, depression and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Germany. J Public Health (Oxf) 2020;42:672-8.

Kennedy BL, Schwab JJ, Morris RL, Beldia G. Assessment of state and trait anxiety in subjects with anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychiatr Q 2001;72:263-76.

Garfin DR, Silver RC, Holman EA. The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychol 2020;39:355-7.

WHO Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Situation Report 86. SUBJECT IN FOCUS: providing timely and accurate information to dispel the “infodemic”. Accessed June 28,2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200415-sitrep-86-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=c615ea20_6.

Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;5:70.

Leppin A, Aro AR. Risk perceptions related to SARS and avian influenza: theoretical foundations of current empirical research. Int J Behav Med 2009;16:7-29.

Boyle J, Brassel T, and Dayton J To get Americans to embrace the COVID-19 vaccine, scientists will need to be the messengers https://www.icf.com/insights/health/covid-19-survey-american-attitudes-vaccine Accessed July 1, 2020.

D’souza G and Dowdy D. What is herd immunity and how can we achieve it with COVID-19? https://www.jhsph.edu/covid-19/articles/achieving-herd-immunity-with-covid19.html. Accessed July 1, 2020.

Fine P, Eames K, Heymann DL. “Herd immunity”: a rough guide. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:911-6.

Wensing M, Sales A, Armstrong R, Wilson P. Implementation science in times of Covid-19. Implement Sci 2020;15:42.

Funding

Institutional Funds (University of Colorado School of Medicine)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Matthew Greenhawt, MD, MBA, MSc: study design, survey design; literature search, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting. He had full access to the data and final responsibility to submit the publication.

Spencer Kimball: study design, survey design, sampling methodology and selection, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting.

Audrey DunnGalvin, PhD, Daniel Munblit, Pasquale Comberiati, MD, Nikita A Nekliudov, Oleg Blyuss, Martin Teufel: survey design, literature search, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting.

Marcus Shaker, MD, MS, Elissa Abrams, MD, Giselle Mosnaim, MD, MS: data analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting. They had full access to the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Matthew Greenhawt was supported by grant #5K08HS024599-02 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality which ended after the study was completed but before manuscript submission; is an expert panel and coordinating committee member of the NIAID-sponsored Guidelines for Peanut Allergy Prevention; has served as a consultant for the Canadian Transportation Agency, Thermo Fisher, Intrommune, and Aimmune Therapeutics; is a member of physician/medical advisory boards for Aimmune Therapeutics, DBV Technologies, Sanofi/Genzyme, Genentech, Nutricia, Kaleo Pharmaceutical, Nestle, Acquestive, Allergy Therapeutics, Pfizer, US World Meds, Allergenis, Aravax, and Monsanto; is a member of the scientific advisory council for the National Peanut Board; has received honorarium for lectures from Thermo Fisher, Aimmune, DBV, Before Brands, multiple state allergy societies, the American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology, the Eurpoean Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; is an associate editor for the Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology; and is a member of the Joint Taskforce on Allergy Practice Parameters.

Spencer Kimball is a Director of Emerson College Polling; a member of the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) and President of the New England Chapter of AAPOR in 2018–2019; an advisor to the Florida Atlantic University Business and Economic Polling Initiative and the City University of New York (CUNY) SPH Foundation, LLC.

Audrey DunnGalvin acts as a consultant for Aimmune Therapeutics and DBV Technologies. She has also received research grants from National Children’s Research Centre, Ireland, and the Food Allergy Research and Resource Program (University of Nebraska-Lincoln).

Elissa Abrams is a collaborator with the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, is on the National Advisory Board for Food Allergy Canada, and is on the National Food Allergy Action Plan Action Steering Team for Food Allergy Canada.

Marcus Shaker is a member of the Joint Taskforce on Allergy Practice Parameters; has a family member who is CEO of Altrix Medical; serves on the Editorial Board of the Journal of Food Allergy and the Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Giselle Mosnaim received research grant support from Astra Zeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Propeller Health; owned stock in Electrocore; and served as a consultant and/or member of a scientific advisory board for GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Regeneron, Teva, Novartis, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Propeller Health.

Pasquale Comberiati, Nikita A Nekliudov, Oleg Blyuss, Martin Teufel: no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Daniel Munblit reports giving paid lectures for Bayer and received funding from the 5–100 Russian Academic Excellence Project.

Clinical Trial Registration

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key Points

Question: Do we fully understand the potential health attitudes towards and psychological effects of the actions taken in the spring of 2020 to help deter the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and COVID-19 disease?

Findings: When assessed just prior to when shelter-in-place orders began to lift in most states, state anxiety was higher and health utility lower that previously established population norms, and associated with the degree of news viewership. In addition, less than 2/3 of adults indicated they would desire COVID-19 vaccination.

Meaning: The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and subsequent response may have had acute, detrimental effects on both state anxiety and health utility, influenced by news viewership. Low desire for vaccines among adults could deter efforts to build herd immunity.

Tweet: The COVID-19 pandemic and response by most states may have had negative effects on short-term anxiety and feelings of one’s present state of good health. In addition, only 2/3 of adults indicated they would desire COVID-19 vaccination.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 80 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greenhawt, M., Kimball, S., DunnGalvin, A. et al. Media Influence on Anxiety, Health Utility, and Health Beliefs Early in the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic—a Survey Study. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 1327–1337 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06554-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06554-y