Online Teaching During COVID-19: Exploration of Challenges and Their Coping Strategies Faced by University Teachers in Pakistan

- 1Department of Education, Sukkur IBA University, Sukkur, Pakistan

- 2Faculty of Economic and Financial Sciences, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

The provision and practice of an online environment have become the main challenge for many institutes including universities during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the use of an online learning system was used by the majority of the teachers through an understanding of the adoption of ICT with the major challenges faced by them during the teaching–learning process. It has been found through this study that the teachers are lacking in ICT literacy. Therefore, they are facing online classroom management and connectivity issues throughout their journey during COVID-19. This study aims to explore the challenges and coping strategies faced by university teachers during the pandemic of COVID-19. A qualitative research method with a case study approach was used to get an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of online teaching during COVID-19. Interviews were collected from eleven teacher educators (TEs) of the university. After analyzing the data, nine themes were generated with major findings, that is, connectivity issues, online teaching methods and techniques, learning environment for online teaching and learning, and challenges faced by teachers. The study findings are a good sought of addition and contribution for the university policymakers to evaluate, influence, and ensure the successful implementation of the e-learning system. Additionally, it is a suggestion for the university management to arrange some workshops or training programs for TEs to improve productivity and performance during their online teaching.

Introduction

In December 2019, a local outbreak of “pneumonia” that was previously unfamiliar, was found in Wuhan city of China, and was rapidly determined to be caused by a novel coronavirus (Dong et al., 2020). After China, it spread to other countries, which is still uncertain (Lau et al., 2020a). Moreover, the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed the disease coronavirus (COVID-19) as a public health emergency. In February 2020, a total of 81,109 COVID-19 cases were confirmed and recorded through laboratory tests worldwide (Guan et al., 2020). COVID-19 spread almost all over the world (Bai et al., 2020), which raised fears, anxiety, and worries among people that destroyed every area of human life including education around the world (Paudel, 2020). The virus forced all systems, especially the education system to move from physical to online through a rapid transition to distance learning to reduce the impact of the virus on all stakeholders. To better control and avoid the spread of the virus, online teaching has become a necessary strategy to restore regular instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic (Chen et al., 2020), where many universities conducted online classes for their safety from COVID-19 (Lei et al., 2021).

Everyone tried their level best to respond to the closure differently with the existing learning methods such as mobile learning, E-learning, and flip classrooms (Almaiah et al., 2020). Similarly, Martin et al. (2019) define online learning as the use of the internet to gain access to teaching materials; interact with knowledge and learners; to gain support in the learning process; and create personal meaning and get success from the learning experiences. Online teaching and learning are part of an educational process that takes place through the internet, which is the medium of distance teaching and learning experiences for both teachers and learners from various places (Kim, 2020). Before the pandemic of COVID-19, e-learning was considered a non-formal activity, but right after the lockdown, it was considered as the need to continue the education system virtually. This online teaching and learning has many educational applications in post-COVID-19, such as Neo, Zoom, Start.me, Google Classroom, Shift, Ted-Ed, Lan School, Blackboard, Edmodo, Class Dojo, Outs, We Video, and many more (Mishra et al., 2020). These apps are very useful to continue the online teaching and learning process even after the pandemic. The quick shift toward the virtual environment brought some challenges for learners and instructors as well, which has been found in a study conducted in the United States that many teachers are beginning to transform their traditional (face-to-face) teaching into an online environment (Hixon et al., 2012) while facing some challenges (Simamora, 2020). Online teaching addresses the issues related to geographical distance and for many other reasons makes the teaching and learning process unproductive (Granena and Yilmaz, 2019; Singh and Thurman, 2019). However, due to the sudden emergence of COVID-19, most of the faculty members are facing issues and challenges like the lack of online tutoring experience, pre-preparation, or support from an educational technology as it requires lesson plans, different teaching materials like audio, video material, and technology support (Bao, 2020).

Due to COVID-19, the majority of the institutes of the world were closed and transferred all their educational activities from traditional to virtual classes. Pakistan, along with other countries has closed all its educational institutes and is trying its best to fulfill the educational loss during the pandemic of COVID-19 (Sahito and Chachar, 2021). To reduce the loss of education systems, many countries are looking for alternatives that could introduce distance learning to manage and tackle the crisis. In this connection, the World Bank (WB) is partnering with the Ministry of Education in several countries to support their efforts to provide distance learning opportunities for learners (Sahito and Chachar, 2021). Pakistan introduced online education with the support of different stakeholders after having many meetings conducted by the Higher Education Commission (HEC), universities, and other concerned government departments. After starting online classes, the main problem was identified that students, teachers, and administrators have low internet access and lack ICT skills (Sahito and Chachar, 2021). According to the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), Pakistan ranks 76 out of 100 countries in terms of availability, affordability, and the ability of people to use the web (Reports, 2021). Pakistan is the fourth largest country in the world with inexpensive or inaccessible internet (Khan, 2019). Therefore, this study is designed to explore the challenges of online teaching faced by university teachers during the pandemic of COVID-19 and their coping strategies in the context of Pakistan. Whereas, some objectives and research questions have been developed to explore the answers to the questions, respectively, to understand the phenomena, for instance: (a) To understand the perception of university teachers about online teaching during COVID-19. (b) To identify the challenges faced by university teachers during online teaching in the COVID-19 period. (c) To explore the coping strategies to overcome challenges of online learning during COVID-19. While the research questions were as follows: (a) What is the perception of university teachers about online teaching during COVID-19? (b) What challenges, issues, and problems are faced by university teachers during online teaching during COVID-19 period? (c). How do university teachers cope to overcome the issues, challenges, and problems of online learning during COVID-19?

As the lockdown ended in most countries, the results of this study would be a good lesson for the institutions and the faculty members to continue their teaching–learning processes by dealing with the challenges and issues that occurred in any difficult situations. Whereas, the developed countries have sound resources to deal with difficult situations, the developing countries are much more behind them to deal with critical situations. Therefore, the findings of this study would be more beneficial for them to learn new techniques of the solutions to their problems within the limited resources.

Literature Review

Online learning is defined as distance learning with the help of electronic devices, for example, tablets, smartphones, laptops, and computers, that require an internet connection (Gonzalez and Louis, 2018; Abbas et al., 2021b). However, the studies in the related literature show the need for the readiness of countries in situations like a pandemic toward education. The global spread of COVID-19 has led to the suspension of classes for more than 850 million students worldwide, disturbing the original teaching plans of schools in all countries and regions (Chen et al., 2020). In the pandemic situation, the students were not allowed to go to school by their governments, institutions, and parents (Abbas et al., 2021a), which was alternated with a shift from traditional education to online education (Basilaia and Kvavadze, 2020). The online library, television broadcasts, guidelines, resources, lectures, and video channels are available online in at least 96 countries (UNESCO, 2020). Additionally, Google had announced that it would offer enterprise video conferencing features such as large meetings for up to 250 people and free recording functionality for G-Suite for Education customers from 1 July 2020. Furthermore, Zoom had removed the video time limit and increased this by accepting the request from China, US, Italy, and Japan. In many countries, selecting the online educational platforms provide chances for university students, teachers and other concerned stakeholders to increase the collaborations and get experience from digitalization (Rowe, 2016). In these years, higher education associations have developed progressively to offer online courses as a major aspect of their curriculum, which is giving access to a wide range of viewers, audiences, and participants to improve, increase, and enhance the learning for educational forms (Soffer and Cohen, 2019). Most of the important elements of online courses are participant engagement and evaluation of the course on low cost and budgets. An advantage of the online course is that it gives the opportunity of strong linkage to the community of participants toward the engagement, participation, integration, and collaboration of course activities (Tanis, 2020) to bring innovation to learning. Online teaching opportunities develop the knowledge and experiences of the teachers to improve the basic qualities of graduates and their programs through social media and many new collaborative online technologies, which are gradually embedded in higher education to make learners familiarized with the context of learning in open online spaces (Rowe, 2016).

Many researchers have compared the results between traditional (face-to-face interaction) and online education for university students, which revealed that the students who have a poor educational background or had lower grades in their previous academic records, perceive online education as a mess of the learning process (Jaggars and Xu, 2016). Similarly, Soffer and Cohen (2019) highlighted that online education increases the dropout ratio of students in the learning process, which can be the cause of failure and social isolation of a learner and economic loss (Lee et al., 2013). In this connection, Palvia et al. (2018) shared their point of view in another way that students who attend online classes have skills to learn individually, they accept diversity, they are much cooperative, and they prefer to work collaboratively. An advantage is that online learning removes social and physical limitations and barriers of the students (Palvia et al., 2018), which is the proper and authentic solution to the problems of the individuals who face issues and problems when delivering high-quality education on their choice of place and time (Lau et al., 2020b).

The role of ICT in teaching, especially in higher education, cannot be reduced (Sahito and Vaisanen, 2017), which is found to be good and supportive for teachers and students (Aljaraideh and Bataineh, 2019). Online learning literature identifies two main reasons that students take online courses: (a) The online delivery model offers greater flexibility and convenience to fulfill all obligations, needs, and requirements of work and family (Xu and Xu, 2019). (b) The challenge associated with online learning is access to ICT resources, as e-learning thrives on the availability of ICT facilities (Arthur-Nyarko and Kariuki, 2019). There is the issue of access to ICT among the different locations of students, households, and areas because the internet, especially 3G networking systems are not the same everywhere (Lembani et al., 2020). ICT issues are not only common in students and areas but are common in teachers’ instructions because ICT is not fully adopted in the process of teaching and learning in most educational institutions (Ghavifekr et al., 2016). Challenges of ICT and e-learning depict all these facts in technologically advanced countries and low economic countries (Sahito and Vaisanen, 2017). This is because both developed and developing countries were facing different challenges, issues, and problems during the pandemic of COVID-19. The main difference is the students’ and teachers’ willingness to accept and use the e-learning system to progress significantly (Almaiah et al., 2016). Previous literature highlighted many challenges of online teaching and learning, which were classified into four categories such as individual challenges, course challenges, teaching challenges, and cultural challenges that vary from country to country because of their different contexts and readiness (Sahito and Vaisanen, 2017). Connectivity issues, lack of ICT knowledge, content delivery, and students’ IT skills were found to be the main challenges during the implementation of online learning in developing countries (Aung and Khaing, 2015). Similarly, Kanwal and Rehman (2017) highlighted that the Pakistani education system has three main challenges in digitization such as computer self-efficacy, system characteristics, and internet experience. Another study suggested that the technical issues, which are the key to the success of e-learning systems, indicate that 45% of e-learning projects in developing countries are complete failures, 40% are partial failures, and only 15% are successful (Al-Araibi et al., 2019). However, the faculty and students say that with an online learning model, they are unable to teach and learn both practical and clinical subjects (Mukhtar et al., 2020) because they can teach and assess the knowledge component only. There is no immediate feedback, teachers cannot assess students’ understanding during online lectures, students have limited attention spans and are intense toward online learning characteristics, which were supported by teachers that during online classes, students misbehave and attempt access to online resources during assessments (Mukhtar et al., 2020).

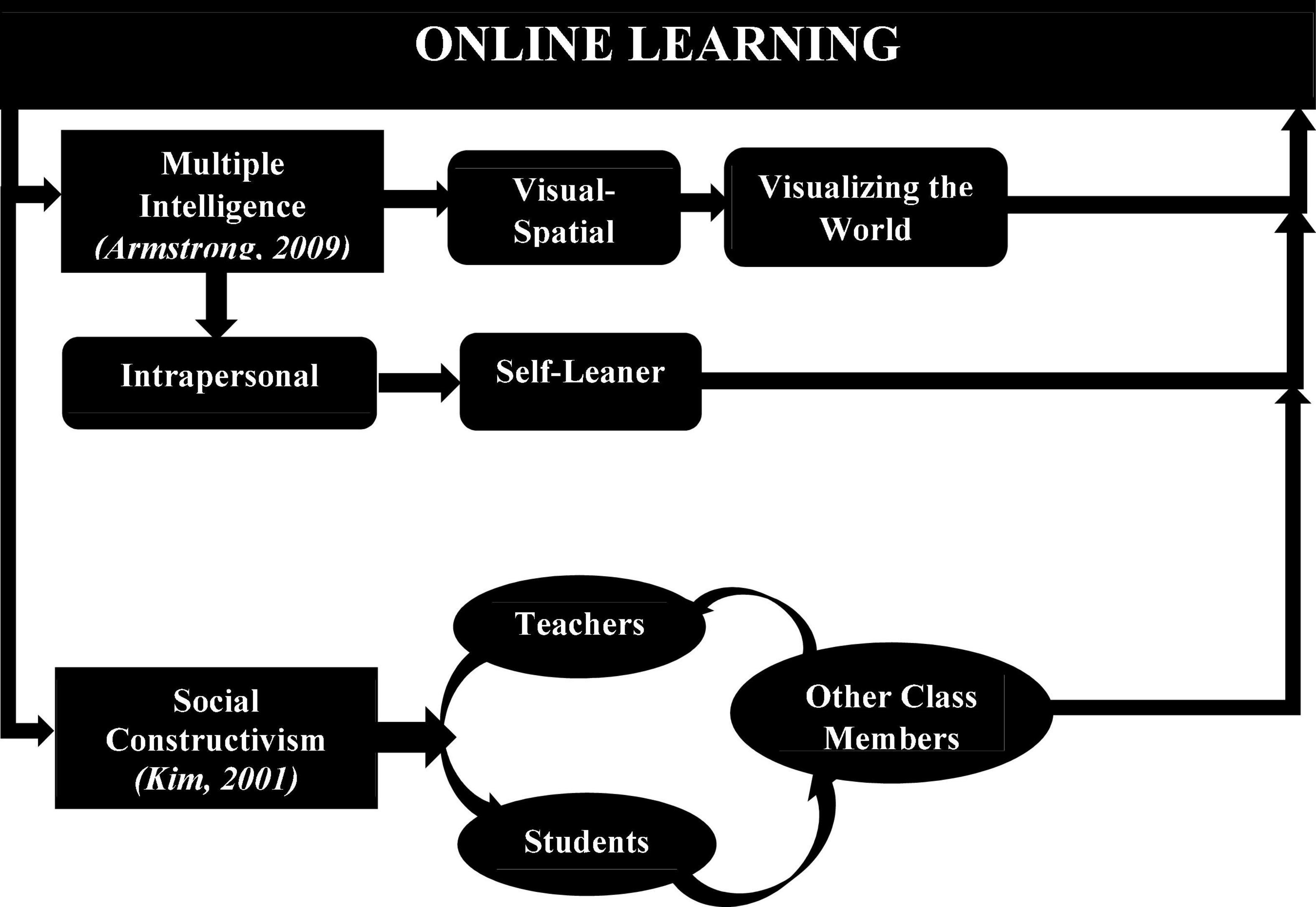

In the theoretical framework (Figure 1), online education is shown as interactive and effective for the teaching and learning process, which is highlighted by Lou (2008) that the rapid growth and development of ICT in teaching has emerged to methods like problem-based learning, case-based learning, interactive learning, task-based learning, and construct of theory belongs to social constructivism suggested by Kim (2001). Moreover, in online classes, most of the teachers try to use a constructivist approach like group work, learner-centered, pair work, cooperation, and project work and its process emphasizes inferential meaning, generates opinions, and develops critical thinking (Paudel, 2020). Where, Visual-Spatial Intelligence can understand patterns of space (Smith, 2002) to understand visual-spatial intelligence and multiple intelligence through the development of capabilities of learners during online education in different terms like art, drawing, jigsaw puzzles, map reading, project making, illusion, illustrations, musician, and naturalistic. The students and teachers can accurately perceive the world due to their sensitivity to visual-spatial aspects, video conferencing, 3D modeling, videos, TV programs, multimedia, and text with images/diagrams/graphics that can be the best tools to unleash their creativity (Paudel, 2020; Sahito and Vaisanen, 2021). Due to their ability to orient themselves in any online activities, they can represent a graphical demonstration by showing their creativity in shapes, colors, lines, and forms (Armstrong, 2009).

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework made by authors with the help of Kim (2001), Armstrong (2009).

Materials and Methods

Philosophical Stance

This study employed multiple intelligence and constructivist approaches as its theoretical framework to explore the teachers’ and students’ challenges and the possible strategies to be adopted during and after COVID-19 in the higher education institutions of Pakistan. The overall picture of a research activity consists of the model linking theoretical values as a specific paradigm (Sarantakos, 2013) of constructivism called a worldview (Creswell, 2014), which is also used by many researchers (Mertens, 2010; Lincoln et al., 2011) and is connected with epistemology (Crotty, 1998) that is broadly conceived as a research methodology (Neuman, 2009).

Research Method and Approach

A qualitative research method was used for this study to gain an in-depth understanding of the online instruction during COVID-19, which allows the researchers to ask open-ended questions from the participants for in-depth statements depending on words, ideas, opinions, etc. (Creswell, 1994, 2014). This approach is used to gain a better understanding of the existing problem in which researchers begin with a general idea and use it as a medium to identify issues that may be of focus for future research. Social constructionism has been used as a philosophical position in which every individual seeks knowledge according to their personal experiences. The researchers believe that every individual has a way to explore the world. Therefore, qualitative research gives an in-depth knowledge of what they experience. The case study approach was used because researchers wanted to explore the phenomenon of online teaching and learning during the COVID time, as Yin (2018) highlighted that case study research is a qualitative approach in which the investigator explores a bounded system (a case) or multiple bounded systems (cases) over time through detailed and in-depth data collection procedures and involves multiple sources of information like observation and document analysis.

Data Collection and Analysis

The data were collected from (n = 11) teacher educators (TEs) through semi-structured interviews and the available documents were also analyzed to make the data authentic. The data were analyzed through a thematic analysis strategy, which is a suitable method for finding, analyzing, and reporting patterns of themes within the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). All conducted interviews were transcribed first, then responses were distributed in different chunks, and such chunks were given the codes to generate the scientific themes. However, the first step in the thematic analysis was to get familiar with the data, which involves the detailed transcription of the collected data. After the coding process, all codes have been combined to form some comprehensive and scientific themes, which have been reviewed, revised, and finalized. Moreover, some categories fall into each other, and then nine themes were founded and finalized, which were refined and defined again to use for final analysis and report writing. The trustworthiness of the data and results were checked through member checks from the interviewees, and then the results were sent to experts in the field for confirmability as an audit trail suggested by Lincoln and Guba (1985).

Results

Interviews allow the researcher to listen to the different, attractive, and meaningful stories of TEs. In this study, eleven (11) TEs were interviewed and found to be impressive in constructing the true primary data for this study to analyze into a narrative and then create a theme. Additionally, the names of participants were kept confidential as per the agreement signed before conducting the interviews. The participants’ names were replaced with teacher educator codes like (TE-1), (TE-2), or TE (3), and so forth, moreover, the essential narratives were recorded, selected, and encoded to analyze the data of the study.

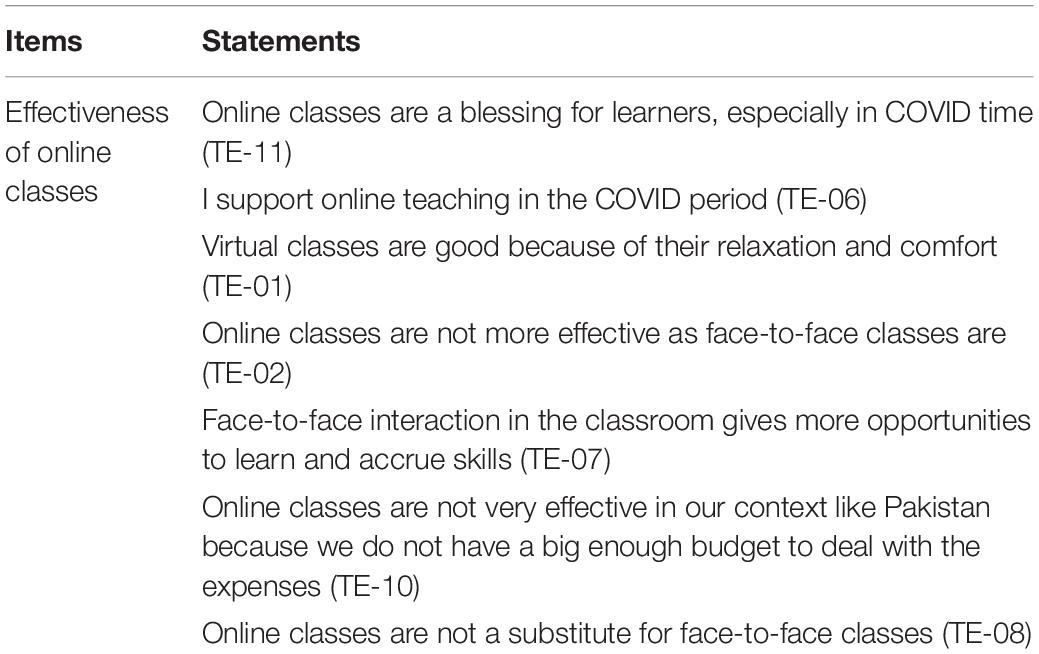

Perception of Teacher Educators About Online Classes

The perception about online classes was extracted from the data in which 64% of TEs perceived that online classes are not the proper and authentic replacement for face-to-face classes. It was found that face-to-face classes have more interaction among students and teachers, which provides more opportunities to discuss everything than online classes. However, TEs perceive online classes as a kind of replacement for relaxation in the educational process, which can be conducted at their ease and in favorable places and times. Table 1 provides a complete perception in detail through direct statements of TEs about online classes during COVID-19.

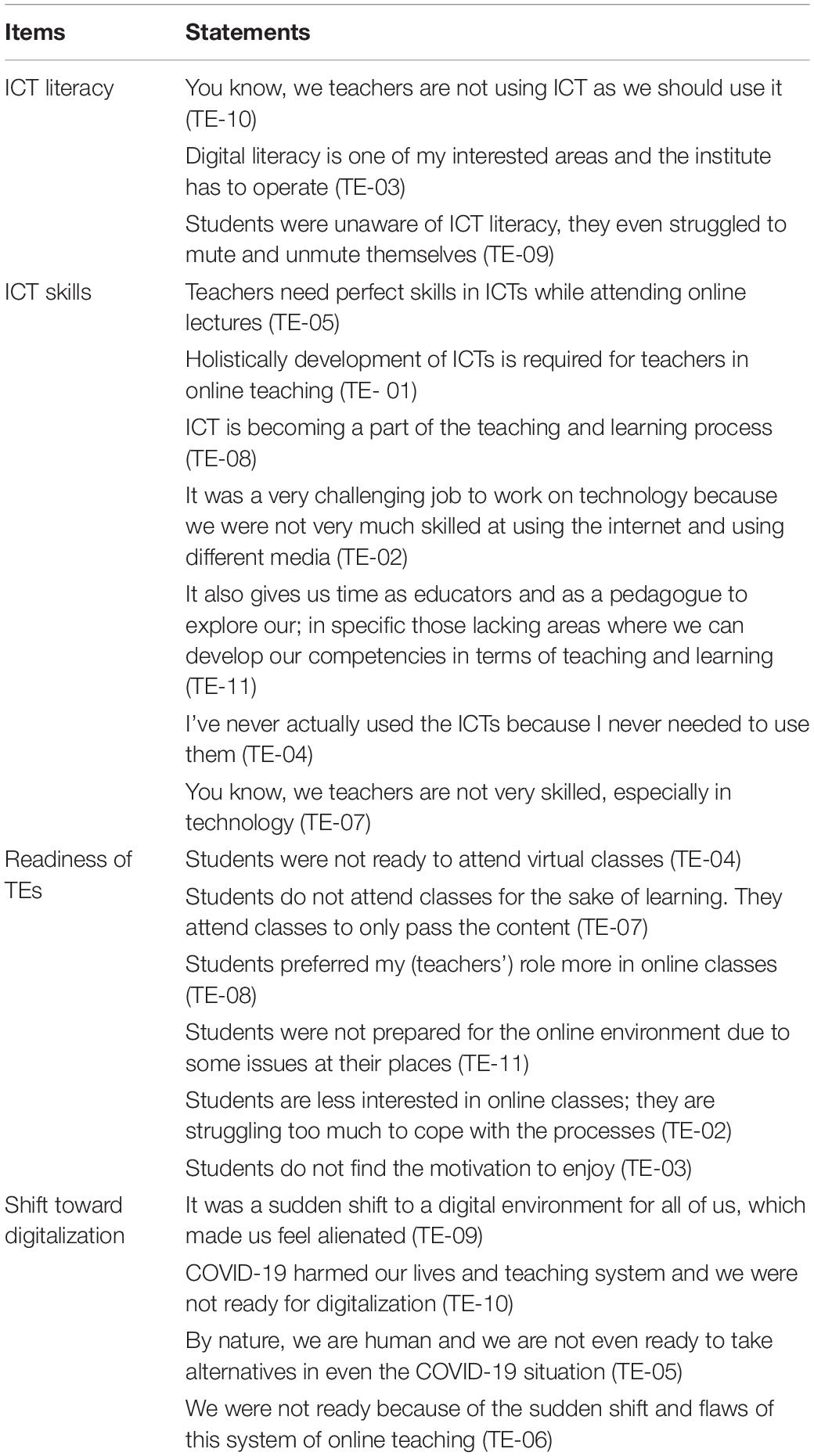

Readiness of Teacher Educators for Online Classes or Learning

About 90% of the TEs perceived holistic development as a key skill that they needed the most in their personal and professional life (Table 2). They perceived ICT skills as an honor and special need during the time of COVID-19. It is not only essential for TEs but necessary for students, a majority of whom do not know the usage of ICTs in online classes. Therefore, the holistic development and readiness of ICT of TEs and students are required to conduct online classes smoothly for better learning to take place.

About 90% of the TEs showed their readiness for online classes, which was found theoretically but the majority of them were not found practically ready for the sudden shift toward online classes. The TEs maintained their readiness with the passage of time, training, counseling, and guidance. The sudden shift toward digitalization harmed the teachers’ and students’ lives because they were not fully prepared for the immediate shift. The TEs and students were facing different challenges, issues, and problems with online classes because they did not attend the classes for getting an education but for “off learning,” which was not enjoyable to them due to its issues and challenges.

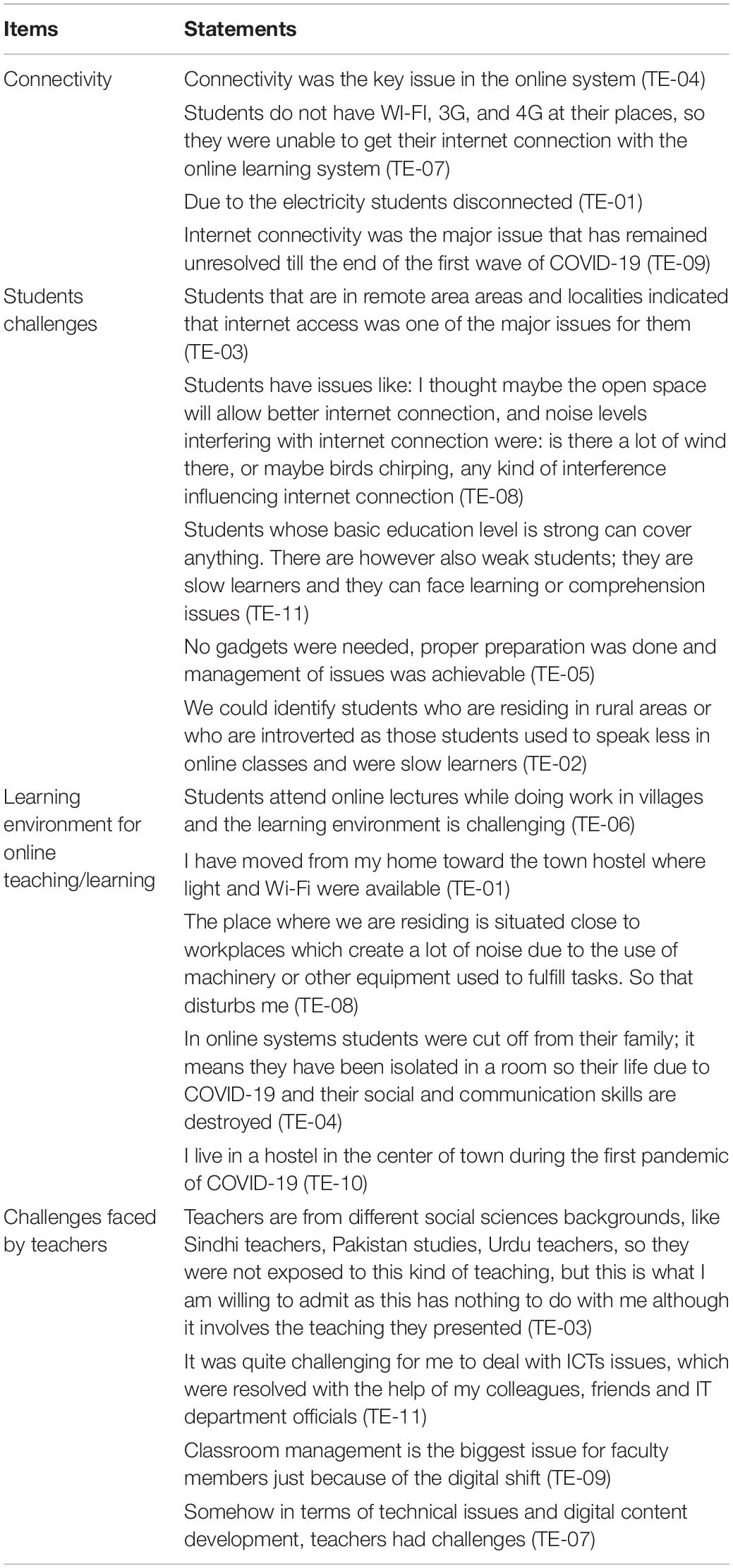

Challenges, Issues, and Problems of Virtual Classes During COVID-19

Challenges and issues in virtual class during the pandemic of COVID-19 was the key theme where 100% of the TEs participated and faced connectivity issues and were not having a proper learning environment (Table 3). Some TEs and learners did not have proper Wi-Fi and 3G connection to attend their online classes. They moved from their small villages to towns and cities and joined hostels where they could get a good internet connection even during the lockdown periods. Some of them belonged to remote areas where they did not have proper electricity connection, which was mentioned by TEs as classroom management issues while teaching online classes as connectivity to the Wi-Fi caused linking and off-line problems.

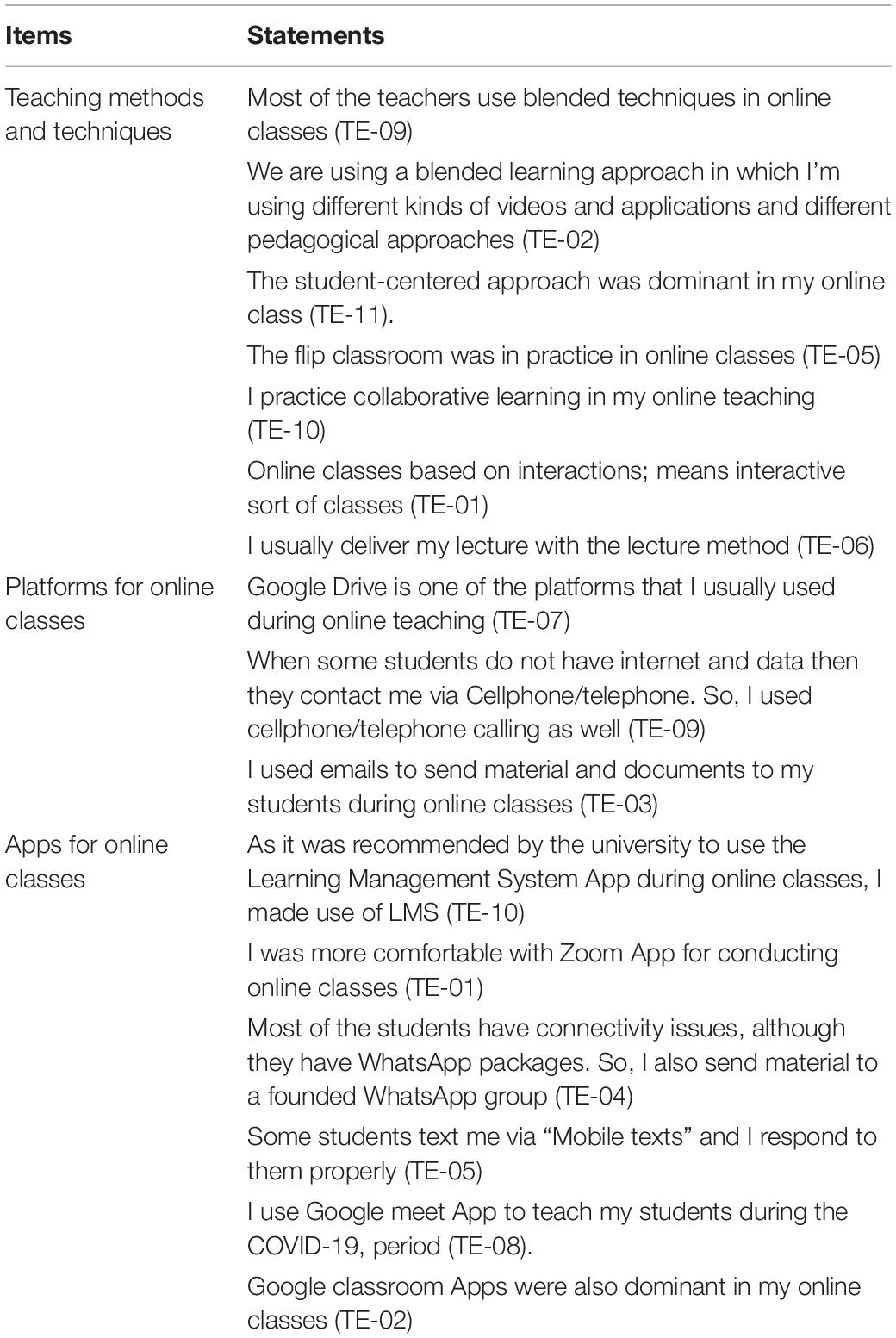

Teaching Instructions, Software Applications, and Platforms Used for Online Classes

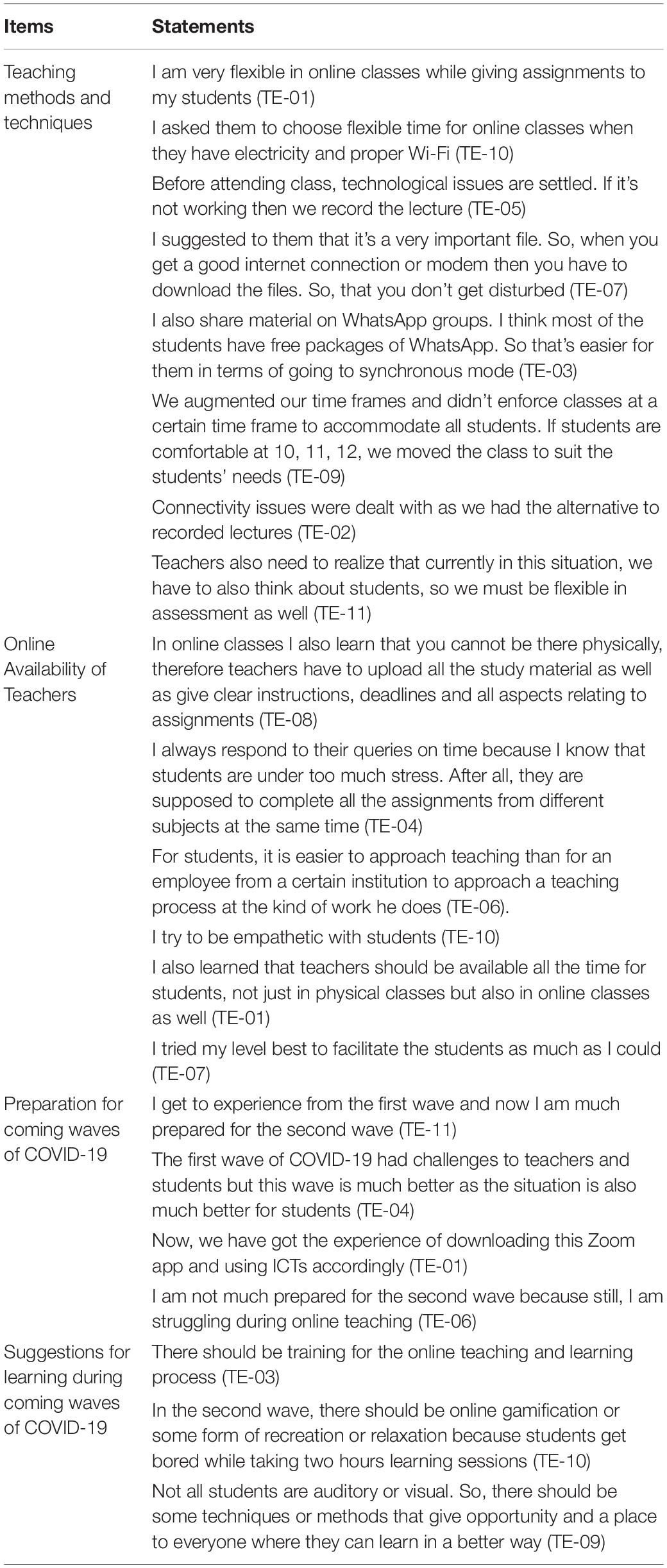

Table 4 provides complete detail about teaching instructions, software applications, and platforms through direct statements of TEs about online classes during COVID-19. About 63% of the TEs talked about the teaching methods and techniques during online classes, which were used by the majority of TEs as a student-centered approach. TEs involve their students in blended mode and discussion to engage them in the discussion forum and collaborative works. However, some teachers were found to use the lectures or traditional methods in their online classes.

The software applications and platforms used for online classes are mentioned as important by TEs. About 81% of the TEs responded that the Learning Management System (LMS) and Zoom App were the dominant apps for conducting online classes during the period of COVID-19. They used the WhatsApp application for the ease of their students in the educational settings of their organizations. Some TEs used SMS service to communicate properly and clearly to maintain the quality of the instructions for their students who had connectivity and internet issues.

Coping Strategies to Solve the Issues and Problems of Online Class During COVID-19 and Preparation for Coming Waves

Table 5 provides complete detail about coping strategies to solve the issues and problems through direct statements of TEs about online classes during COVID-19. About 100% of the TEs discussed coping strategies to solve the issues and problems of online classes during COVID-19. The TEs remained flexible to conduct online classes and show their availability to students during online teaching. The TEs overcame the issues of connectivity and electricity via recording the whole class and sending it to students so they could listen when they had a good internet connection. The TEs were available 24/7 to their students because they perceived that students suffer a lot from COVID-19 and online teaching. In the table below are the subsequent statements of the TEs who revealed their coping strategies.

Most of the TEs have experience with online classes in the first wave of COVID-19 and all of them are prepared for the second wave of COVID-19 regarding online education. About 63% of the TEs show their readiness for the second wave of online classes and they prepared themselves with a much better teaching style. About 10% of the TEs were not prepared for digitalization yet because they lacked ICT literacy, which is a prerequisite for the preparation of online classes through multi-methods in digitalization. After all, learners possess various levels of intelligence.

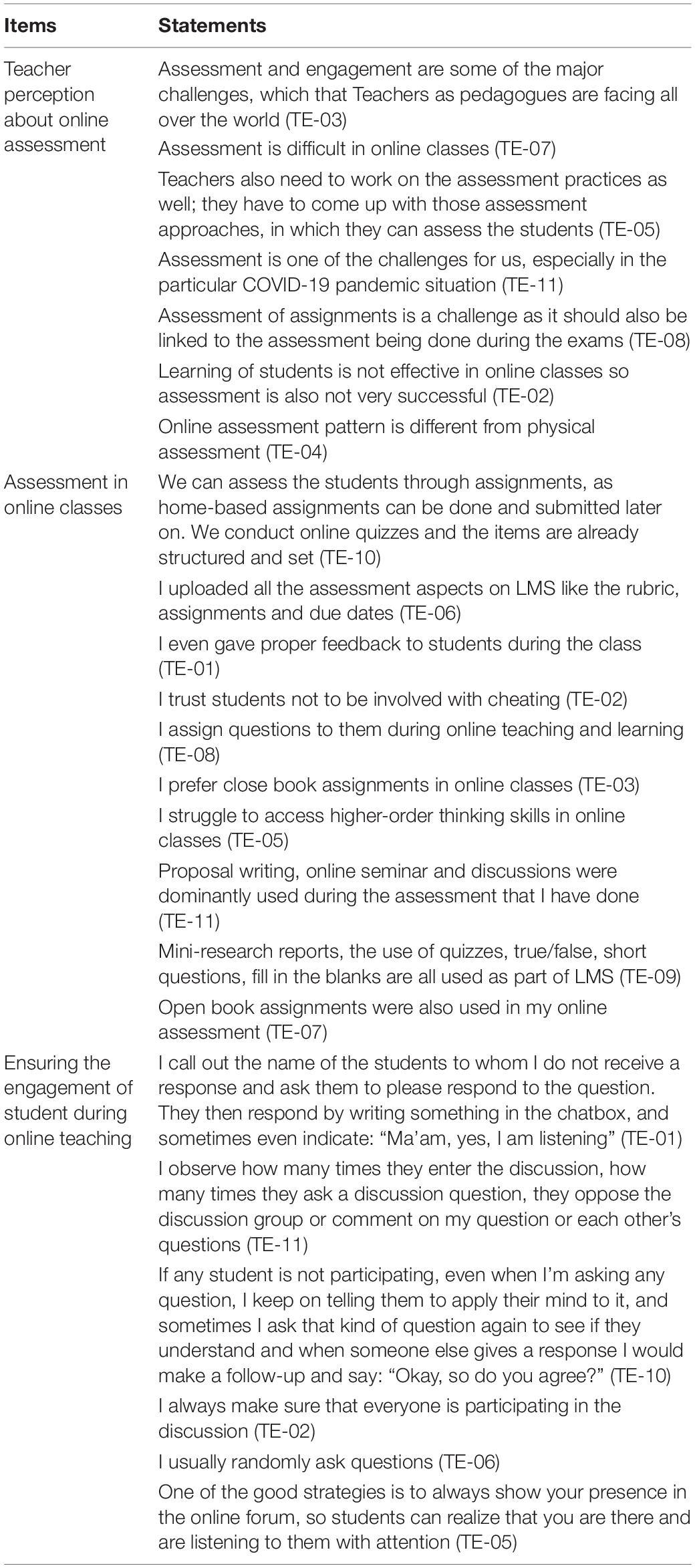

Students’ Engagement and Assessment in Online Classes

About 100% of the TEs shared their experience about the engagement and assessment of students in online classes where they share their perceptions about online assessment (Table 6). However, they perceive online assessment as the most difficult part of digitalization. They talked about the assessment of the way they assess students like they promote discussion forums, arrange online seminars, allow them to write mini-research reports, and the like. On the other hand, TEs ensure the engagement of students by asking random questions during online classes as TEs do both formative and summative assessments to ensure the engagement of students.

Discussion

The study suggested several findings on online teaching during the COVID-19 time frame. However, nine findings have emerged from the collected data from TEs. These include the following: Perception of TEs about Online Classes (PTEOC), Holistic Development of Teacher Educators in ICT (HDTEICT), Readiness of Prospective Teachers about Online Classes (RPTOC), Challenges and Issues of Virtual Classes during COVID-19 (CIVCC), Teaching Instructions for Online Classes (TIO), Software Applications and Platform used for Online Classes (SAPUOC), Coping Strategies to Solve the Issues and Problems of Online Class during COVID (CSSIP), Readiness for Second Wave of COVID-19 (RSWC), and Students’ Engagement and Assessment in Online Classes (SEAOC).

The first finding of this study highlighted the perception of teachers regarding online classes as TEs perceived that virtual classes do not replace physical classes because physical classes are more affected by teaching and learning than virtual classes. The same findings are supported by Astuti and Solikhah (2020) as online classes in the time of COVID-19 are not very effective because students are not familiar with digitalization. Likewise, another study suggested that students are not motivated for online classes because of their sudden shift toward virtualization (Kulal and Nayak, 2020). Additionally, Kalloo et al. (2020) support the thoughts of Astuti that online classes could not replace the social needs of learners and instructors. Likewise, Nambiar (2020) highlighted that there is a significant difference between face-to-face classes and online classes in the time of pandemic situations because students gain less in online classes as compared to physical classes. Moreover, TEs perceive online teaching not as a substitute for physical teaching because in physical classes, teachers can understand the non-verbal language of learners (Uzunboylu and Ozdamli, 2011). However, TEs have tasks and responsibilities that cannot be easily transferred when they have to switch from a face-to-face learning system to an online system with online learning experiences that have never been implemented before (Aliyyah et al., 2020).

The second finding of the study revealed that Holistic development in ICT is needed for the twenty-first century. ICT has become a part of our daily lives (Olowe and Kutelu, 2014). To get full benefits of ICT in learning for education, pre-service and in-service teachers must have the basic ICT skills and qualifications (Collis and Jung, 2003). In the time of the COVID-19 scenario, educators require more ICT skills to communicate virtually with learners. The study pointed out that some TEs themselves were inexperienced in the use of ICT during online teaching; they were lacking to record the session and they were unable to use multiple screens at a time (Rahiem, 2020). This study exposed that TEs were not ready for the sudden shift toward online classes, which is supported by Anwar et al. (2020) that learners were not ready to accept the sudden shift toward digitalization because they did not have enough resources and skills. Initially, the students and teachers were not found fully ready for online teaching (Cutri and Mena, 2020) but after training and availability of resources, they started to work. In contrast to this finding, developed countries were much more ready for online classes because they have enough gadgets and resources to shift their classes toward digitalization (Zawacki-Richter, 2020).

It was also found that students and teachers both were facing challenges during online classes such as connectivity issues. Students were not much familiar with digitalization and they did not have a proper learning/teaching environment. Similarly, Anwar et al. (2020) highlighted that students and teachers living in remote areas were facing difficulties due to slow internet and connection problems, and people in towns also found it challenging. Moreover, Bayern (2020) reported that more than 40% of the respondents said that there were connectivity problems during COVID-19 and it had a negative impact on their life and their family member’s education. The results tell some common problems that learners have encountered including loss of internet or data during an online class, inability to load content, and bad audio or video during class due to slow internet. Even some of the students did not have internet access in their homes. Many times, students had to travel a few kilometers away to some other areas to get proper and strong signals to attend their classes and submit their assignments online. This study further reveals that TEs use a student-centered approach, even in online classes, involving students in discussion forums, presentations, seminars, and group work. Likewise, the literature supports that teachers use multiple methods to conduct online classes for the betterment of learners (Babinčáková and Bernard, 2020). Some other studies present this concept in another direction that online teaching is problematic and teachers cannot create more advanced teaching strategies using the online system (Anyiendah, 2017). The finding of another study suggested that educators use different online tools for teaching, including synchronous, LMS, Zoom, WhatsApp, Google app, and asynchronous activities (Lima et al., 2020).

Teachers cope with the challenges of online teaching by making themselves available to learners and being flexible to assist them, which is supported by the fact that teachers’ flexibility with time frames during online classes is much more effective because it increases the level of achievement among students (Mahmood, 2020). It was mentioned that a flexible teaching approach is essential for learning as it is important not only for students but also for teachers’ professionalism (Netcom 92, 2021). In support of these ideas, Leila et al. (2021) shared her view that teachers’ flexibility in the teaching process leads them to believe in the inner capabilities of learners and give them space and time to show their innovation. Additionally, the flexibility of teachers is an advantage for learners to reduce academic pressure. During online teaching, teachers were available to their students to help them in learning and for cognitive support, because some of the causal effects of COVID-19 led to connectivity issues due to a lack of internet and failure to have contact with the students for 24 h a day throughout the week (Shah, 2021).

Assessment is one of the key issues in online classes, and an aspect supported by Zulaiha et al. (2020) as they noted that assessment is the core challenge in the online teaching and learning process. Similar to this, another study indicated that assessment in e-learning is much more difficult because educators are only testing the knowledge of students (Elzainy et al., 2020). As the present study mentions that the formative assessment done during the class shows that formative assessments reflect the nature of online learning and keep students responsible for their studies. This is because the online assessments help learners to demonstrate their ability to think, analyze, and do problem-solving, which is a key benefit of the change from traditional teaching and learning with primarily teacher facilitation (Alsadoon, 2017).

Implications of the Study

• This study contributes to exploring the significant challenges faced by university teachers to implement e-learning during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

• It also explores the influencing factors of e-learning implementation used during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

• It is also exploring the coping strategies of university teachers to meet the challenges of e-learning implementation in Pakistan during the pandemic of COVID-19.

• This study gives the roadmap for teachers to teach differently in hard areas while learning digitally.

• It can be seen as a guide to improving the implementation of the e-learning systems among teachers and students.

• The best practices of teachers and management will be a lesson for others.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the significant challenges and influencing factors for e-learning used during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Such usage and process cover the challenges of digitalization that were not examined previously. The results of this research are based on empirical evidence, which identifies the challenges of online classes faced by university teachers. However, the university, policymakers, designers, and producers of the universities can benefit from the findings, which provide a true picture of the current learning system in the times of COVID-19. It can be seen as a guide to improving the implementation of e-learning systems among teachers.

A total of nine themes were found to analyze the current situation of online classes in Pakistan, which suggested that online assessment was the main issue. Most of the teachers use a student-centered approach during the pandemic. However, teachers were facing the challenges of ICT literacy, classroom management, and connectivity during the shift toward digitalization. Therefore, it is a suggestion for the university management to arrange training programs for TEs so that they can run online classes smoothly.

Limitations and Future Direction of the Study

The study is limited to qualitative research methods, whose results cannot be generalized. Therefore, it is suggested to future researchers conduct the same study with quantitative methods for generalization. The data for the study were collected from a few universities, which can be further enhanced through future researchers to collect data from more universities, that is, public and may be private.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Committee of the Department of Education, SIBAU, Sukkur, Sindh, Pakistan. Patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

ZS did the introduction, literature review, result writing, and final version setting. SS did the literature review and data collection. A-MP did the instrumentation development and discussion. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbas, A., Hosseini, S., Núñez, J. L. M., and Sastre-Merino, S. (2021b). Emerging technologies in the education for innovative pedagogies and competency development. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 37, 1–5. doi: 10.14742/ajet.7680

Abbas, A., Hosseini, S., Escamilla, J., and Pego, L. (2021a). “Analyzing the emotions of students’ parents at higher education level throughout the COVID-19 pandemic: an empirical study based on demographic viewpoints,” in Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Piscataway, NJ. doi: 10.1109/EDUCON46332.2021.9454041

Al-Araibi, A. A. M., Naz’ri Bin Mahrin, M., and Yusoff, R. C. M. (2019). Technological aspect factors of ELearning readiness in higher education institutions: Delphi technique. Educ. Inf. Technol. 24, 567–590. doi: 10.1007/s10639-018-9780-9

Aliyyah, R. R., Rachmadtullah, R., Samsudin, A., Syaodih, E., Nurtanto, M., and Tambunan, A. R. S. (2020). The perceptions of primary school teachers of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic period: a case study in Indonesia. J. Ethnic Cult. Stud. 7, 90–109. doi: 10.29333/ejecs/388

Aljaraideh, Y., and Bataineh, K. A. (2019). Jordanian students’ barriers of utilizing online learning: a survey study. Int. Educ. Stud. 12, 99–108. doi: 10.5539/ies.v12n5p99

Almaiah, M. A., Al-Khasawneh, A., and Althunibat, A. (2020). Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the e-learning system usage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Inf. Technol. 25, 5261–5280. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10219-y

Almaiah, M. A., Jalil, M. A., and Man, M. (2016). Preliminary study for exploring the major problems and activities of mobile learning system: a case study of Jordan. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 93, 580–594.

Alsadoon, H. (2017). Students’ Perceptions of e-assessment at Saudi Electronic University. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 16, 147–153.

Anwar, M., Khan, A., and Sultan, K. (2020). The Barriers and challenges faced by students in online education during the COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan. Gomal Univ. J. Res. 36, 52–62.

Anyiendah, M. S. (2017). Challenges faced by teachers when teaching english in public primary schools in Kenya. Front. Educ. 2:13. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00013

Arthur-Nyarko, E., and Kariuki, M. G. (2019). Learner access to resources for eLearning and preference for eLearning delivery mode in distance education programs in Ghana. Int. J. Educ. Technol. 6, 1–8. doi: 10.18415/ijmmu.v4i3.73

Astuti, M., and Solikhah, I. (2020). Teacher Perception in Teaching English for SMP in Klaten Regency during COVID-19 Outbreak. IJOTL-TL 6, 1–13.

Aung, T. N., and Khaing, S. S. (2015). “Challenges of implementing e-learning in developing countries: a review,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computing, Cham. doi: 10.1002/j.1681-4835.2009.tb00271.x

Babinčáková, M., and Bernard, P. (2020). Online experimentation during COVID-19 secondary school closures: teaching methods and student perceptions. J. Chem. Educ. 97, 3295–3300. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00748

Bai, Y., Yao, L., Wei, T., Tian, F., Jin, D. Y., Chen, L., et al. (2020). Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA 323, 1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565

Bao, W. (2020). COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: a case study of Peking University. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2, 113–115. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.191

Basilaia, G., and Kvavadze, D. (2020). Transition to online education in schools during a SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Georgia. Pedagogical Res. 5, 1–9.

Bayern, M. (2020). Connectivity Issues Hamper Remote Learning during COVID-19 Crisis. Available online at: https://www.techrepublic.com/article/connectivity-issues-hamper-remote-learning-during-covid-19-crisis/ (accessed Aug 26, 2021).

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chen, T., Peng, L., Jing, B., Wu, C., Yang, J., and Cong, G. (2020). The Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on user experience with online education platforms in China. Sustainability 12:7329. doi: 10.3390/su12187329

Collis, B., and Jung, I. S. (2003). “Uses of information and communication technologies in teacher education,” in Teacher Education through Open and Distance Learning eds B. Robinson & C. Latchem (Milton Park: RoutledgeFalmer), 171–192.

Creswell, J. W. (1994). Research Design: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication, Inc.

Crotty, M. (1998). The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Cutri, R. M., and Mena, J. (2020). A critical reconceptualization of faculty readiness for online teaching. Distance Educ. 41, 361–380. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2020.1763167

Dong, E., Du, H., and Gardner, L. (2020). An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real-time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1

Elzainy, A., El Sadik, A., and Al Abdulmonem, W. (2020). Experience of e-learning and online assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic at the College of Medicine. Qassim University. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 15, 456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2020.09.005

Ghavifekr, S., Kunjappan, T., Ramasamy, L., and Anthony, A. (2016). Teaching and Learning with ICT Tools: issues and challenges from teachers’, perceptions. Malays. Online J. Educ. Technol. 4, 38–57. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03851

Gonzalez, D., and Louis, R. St (2018). “Online Learning,” in The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, 1st Edn, ed. J. I. Liontas (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), doi: 10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0423

Granena, G., and Yilmaz, Y. (2019). Corrective feedback and the role of implicit sequence-learning ability in l2 online performance. Lang. Learn. 69, 127–156. doi: 10.1111/lang.12319

Guan, W. J., Ni, Z. Y., Hu, Y., Liang, W. H., Ou, C. Q., He, J. X., et al. (2020). Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1708–1720.

Hixon, E., Buckenmeyer, J., Barczyk, C., Feldman, L., and Zamojski, H. (2012). Beyond the early adopters of online instruction: motivating the reluctant majority. Internet High. Educ. 15, 102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.11.005

Jaggars, S., and Xu, D. (2016). How do online course design features influence student performance? Comput. Educ. 95, 270–284. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.01.014

Kalloo, R. C., Mitchell, B., and Kamalodeen, V. J. (2020). Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in Trinidad and Tobago: challenges and opportunities for teacher education. J. Educ. Teach. 46, 452–462. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1800407

Kanwal, F., and Rehman, M. (2017). Factors affecting e-learning adoption in developing countries– empirical evidence from Pakistan’s higher education sector. IEEE Access 5, 10968–10978. doi: 10.1109/access.2017.2714379

Khan, A. (2019). Access to the Internet. Available at Pakistantoday.com.pk. Available online at: https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2019/10/04/access-to-the-internet/ (accessed Jul 5, 2020).

Kim, B. (2001). “Social constructivism,” in Emerging Perspectives on Learning, Teaching and Technology, ed. M. Orey. Available online at: http://relectionandpractice.pbworks.com/f/Social+Constructivism.pdf (accessed September 25, 2007).

Kim, J. (2020). Learning and teaching online during COVID-19: experiences of student teachers in an early childhood education practicum. Int. J. Early Child. 52, 145–158. doi: 10.1007/s13158-020-00272-6

Kulal, A., and Nayak, A. (2020). A study on perception of teachers and students toward online classes in Dakshina Kannada and Udupi District. Asian Assoc. Open Univ. J. 15, 285–296. doi: 10.1108/aaouj-07-2020-0047

Lau, H., Khosrawipour, V., Kocbach, P., Mikolajczyk, A., Ichii, H., Schubert, J., et al. (2020a). Internationally lost COVID-19 cases. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 53, 454–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.013

Lau, J., Bin, Y., and Dasgupta, D. (2020b). Will the Coronavirus make Online Education go Viral? https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/will-coronavirus-make-online-education-go-viral (accessed Aug 26, 2021).

Lee, Y., Choi, J., and Kim, T. (2013). Discriminating factors between completers of and dropouts from online learning courses. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 44, 328–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01306.x

Lei, T., Cai, Z., and Hua, L. (2021). 5G-oriented IoT coverage enhancement and physical education resource management. Microprocess. Microsyst. 80:103346. doi: 10.1016/j.micpro.2020.103346

Leila, N., Kayed, A. L., and Assaf, A. (2021). Reinventing how Teachers and Leaders Co-Generate Equitable Evaluation Practices for Teacher Growth and Development. Ph.D. thesis. Available online at: https://thescholarship.ecu.edu/bitstream/handle/10342/9063/KAYED-DOCTORALDISSERTATION-2021.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed Aug 26, 2021).

Lembani, R., Gunter, A., Breines, M., and Dalu, M. S. (2020). The same course, different access: the digital divide between urban and rural distance education students in South Africa. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 44, 70–84. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2019.1694876

Lima, K. R., das Neves, B. S., Ramires, C. C., Soares, M. S., Martini, V. A. V., Luiza Freitas Lopes, L. F., et al. (2020). Student assessment of online tools to foster engagement during the COVID-19 quarantine. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 44, 679–683. doi: 10.1152/advan.00131.2020

Lincoln, Y. S., Lynham, S. A., and Guba, E. G. (2011). “Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences revisited,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th Edn, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 97–128.

Lou, W. (2008). Cultivating the Capacity for Reflective Practice: A Professional Development case Study of L2/EFL Teachers. Ph.D. thesis. Kent, OH: Kent State University.

Mahmood, S. (2020). Instructional Strategies for Online Teaching in COVID-19 Pandemic. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 3, 199–203. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.218

Martin, F., Budhrani, K., Kumar, S., and Ritzhaupt, A. (2019). Award-winning faculty online teaching practices: roles and competencies. Online Learn. 23, 184–205.

Mertens, D. M. (2010). Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mishra, L., Gupta, T., and Shree, A. (2020). Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 1:100012. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100012

Mukhtar, K., Javed, K., Arooj, M., and Sethi, A. (2020). Advantages, Limitations and Recommendations for online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 36, S27–S31. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2785

Nambiar, D. (2020). The impact of online learning during COVID-19: students’ and teachers’ perspectives. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 8, 783–793.

Netcom 92 (2021). Flexible Teaching: What It Is and Why You Should Use It? Netcom 92. Available online at: https://www.netcom92.com/2017/05/importance-of-flexible-teaching (accessed Aug 26, 2021).

Neuman, W. L. (2009). Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 7th Edn. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Olowe, P. K., and Kutelu, B. O. (2014). Perceived importance of ICT in preparing early childhood education teachers for the new generation children. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 3, 119–124.

Palvia, S., Aeron, P., Gupta, P., Mahapatra, D., Parida, R., Rosner, R., et al. (2018). Online education: worldwide status, challenges, trends, and implications. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manage. 21, 233–241. doi: 10.1080/1097198x.2018.1542262

Paudel, P. (2020). Online education: benefits, challenges and strategies during and after COVID-19 in higher education. Int. J. Stud. Educ. 3, 70–85. doi: 10.46328/ijonse.32

Rahiem, M. D. (2020). Technological barriers and challenges in the use of ICT during the COVID-19 emergency remote learning. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 8, 6124–6133. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2020.082248

Reports, S. (2021). COVID-19 Reveals the Divide in Internet Access in Pakistan - BORGEN. Available online at: https://www.borgenmagazine.com/internet-access-in-Pakistan/ (accessed Jan 27, 2021).

Rowe, M. (2016). Developing graduate attributes in an open online course. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 47, 873–882. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12484

Sahito, Z., and Chachar, G. B. (2021). “COVID – 19 and the educational leadership & management,” in Emerging Trends and Strategies for Industry 4.0: During and Beyond COVID – 19, eds B. Akkaya, K. Jermsittiparsert, M. A. Malik, and Y. Kocyigit (Warsaw: Sciendo Publishers), 117–128. doi: 10.2478/9788366675391-003

Sahito, Z., and Vaisanen, P. (2017). Effect of ICT Skills on the Job Satisfaction of Teacher Educators: evidence from the Universities of the Sindh Province of Pakistan. Int. J. High. Educ. 6, 122–136. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v6n4p122

Sahito, Z., and Vaisanen, P. (2021). Job satisfaction and the motivation of teacher educators towards quality education: a case study approach. SYLWAN 165, 46–64.

Shah, S. (2021). Online Classes Stress Out Students, Teachers During Pandemic. Available online at: https://www.dawn.com/news/1576427 (accessed Jan 23, 2021).

Simamora, R. M. (2020). The Challenges of Online Learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: an essay analysis of performing arts education students. Stud. Learn. Teach. 1, 86–103. doi: 10.46627/silet.v1i2.38

Singh, V., and Thurman, A. (2019). How many ways can we define online learning? A systematic literature review of definitions of online learning (1988-2018). Am. J. Distance Educ. 33, 289–306. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2019.1663082

Smith, M. K. (2002). Howard Gardner and Multiple Intelligences, The Encyclopedia of Informal Education. Available online at: http://www.infed.org/thinkers/gardner.htm (accessed January 28, 2008).

Soffer, T., and Cohen, A. (2019). Students’ engagement characteristics predict success and completion of online courses. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 35, 378–389. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12340

Tanis, C. J. (2020). The seven principles of online learning: feedback from faculty and alumni on its importance for teaching and learning. Res. Learn. Technol. 28:2319.

UNESCO (2020). UNESCO Report, ‘National Learning Platforms and Tools. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/nationalresponses (accessed Apr 4, 2021).

Uzunboylu, H., and Ozdamli, F. (2011). Teacher perception form-learning: scale development and teachers’ perceptions. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 27, 544–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00415.x

Xu, D., and Xu, Y. (2019). The Promises and Limits of Online Higher Education: Understanding How Distance Education Affects Access, Cost, and Quality. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Zawacki-Richter, O. (2020). The current state and impact of COVID-19 on digital higher education in Germany. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. [Epub ahaed of print]. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.238

Keywords: online teaching, COVID-19, coping strategies, challenges, connectivity, ICT skills

Citation: Sahito Z, Shah SS and Pelser A-M (2022) Online Teaching During COVID-19: Exploration of Challenges and Their Coping Strategies Faced by University Teachers in Pakistan. Front. Educ. 7:880335. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.880335

Received: 21 February 2022; Accepted: 01 April 2022;

Published: 30 June 2022.

Edited by:

Vicki S. Napper, Weber State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Asad Abbas, Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (ITESM), MexicoAngela Page, The University of Newcastle, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Sahito, Shah and Pelser. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zafarullah Sahito, zafarullah.sahito@gmail.com

Zafarullah Sahito

Zafarullah Sahito Sayeda Sapna Shah

Sayeda Sapna Shah Anna-Marie Pelser

Anna-Marie Pelser