- 1Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

- 2Global Health Institute, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

- 3National Health Commission Key Lab of Radiation Biology, Jilin University, Changchun, China

The healthcare systems in China and globally have faced serious challenges during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. The shortage of beds in traditional hospitals has exacerbated the threat of COVID-19. To increase the number of available beds, China implemented a special public health measure of opening mobile cabin hospitals. Mobile cabin hospitals, also called Fangcang shelter hospitals, refer to large-scale public venues such as indoor stadiums and exhibition centers converted to temporary hospitals. This study is a mini review of the practice of mobile cabin hospitals in China. The first part is regarding emergency preparedness, including site selection, conversion, layout, and zoning before opening the hospital, and the second is on hospital management, including organization management, management of nosocomial infections, information technology support, and material supply. This review provides some practical recommendations for countries that need mobile cabin hospitals to relieve the pressure of the pandemic on the healthcare systems.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has become a health catastrophe, and healthcare systems worldwide have been overwhelmed by the new surge of infections (1). The substantial medical needs of the large number of COVID-19 patients are straining the healthcare system in India, where the wards are limited (2). Dr. Anthony Fauci, a top pandemic expert and the chief medical advisor of the U.S. government, made the following recommendations to control the pandemic in India: establishing lockdown for a couple of weeks, setting up emergency units as hospitals as done in China, and having a central organization (3). The emergency units mentioned refer to China's mobile cabin hospitals.

Mobile cabin hospital, also called Fangcang shelter hospital, is a type of modular health equipment providing multiple functions, such as isolation, triage, basic medical care, frequent monitoring, rapid referral, and essential living needs (4). Mobile cabin hospitals help solve the issues of bed shortages and separate mild cases from serious ones (5). According to the clinical manifestations, COVID-19 cases can be divided into mild, moderate, severe, and critical types (6). Approximately 80% of the COVID-19 cases are of the mild or moderate types that do not require intensive care, and these patients are able to walk around by themselves. Without centralized management, the infection can spread rapidly in the community (7, 8). In the early stages of the epidemic, medical facilities were insufficient (9). To ensure early isolation and treatment of mild and moderate cases, the Chinese government designed and built mobile cabin hospitals (10). Mobile cabin hospitals provided a large number of beds for mild and moderate COVID-19 cases, excluding the elderly, pregnant women, and those with pre-existing health conditions. This changed the family-based quarantine approach into group isolation of mild cases, obviating within-household and community transmissions (11–13).

The World Health Organization has recommended “cohort nursing” for large outbreaks, such as influenza (14). Cohort nursing refers to the grouping of patients with the same laboratory-confirmed pathogen in the same isolated area (15). The main difference between cohort nursing and mobile cabin hospitals is that patients are placed in the existing wards in the former, whereas the latter are usually created by converting large-scale public venues such as indoor stadiums, conference centers, or exhibition centers (16). When there are numerous patients and insufficient wards, mobile cabin hospitals can be recommended as an alternative strategy to cohort nursing to control the spread of disease. With the characteristics of rapid construction, massive scale, and low cost, the mobile cabin hospitals can effectively relieve the pressure of the pandemic on healthcare systems (4). For example, the construction of the Hongshan Sports Stadium mobile cabin hospital took only 37 h and admitted over 1,000 patients (17). Since February 5, 2020, 16 mobile cabin hospitals were functional in Wuhan, providing more than 13,000 beds and admitting over 12,000 patients with COVID-19 (16). All patients of the 16 mobile cabin hospitals were discharged by March 10, 2020, and no deaths were reported (18).

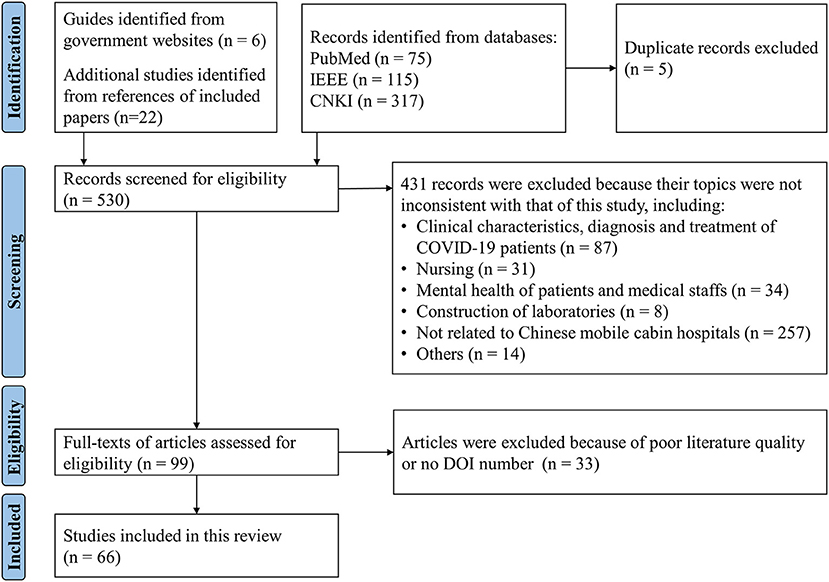

This article aims to review China's experience in operating mobile cabin hospitals to provide a reference for other countries that can utilize mobile cabin hospitals to relieve the pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare systems. The search terms and literature reviewing process were shown in Supplementary Materials and Figure 1. We believe that this experience is valuable even for preparedness against the future outbreak of other respiratory infectious diseases.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the screening process for the literature included in this review.

Preparedness of Mobile Cabin Hospitals

Site Selection

To serve as mobile cabin hospitals, the public buildings should meet the following criteria (10, 19–24):

① Road accessibility, for example, proximity to arteries and main roads;

② Away from the headwaters and densely populated areas;

③ Spacious outdoor area and sufficient indoor space;

④ Presence of electrical, plumbing, and ventilation systems and other infrastructure (buildings with mechanical ventilation systems preferred);

⑤ Easy to remodel, such as interior equipment that can be rapidly removed;

⑥ Fireproof degree and firefighting facilities compliant with fire regulations.

Conversion of Public Venues Into Hospitals

The design and remodeling of mobile cabin hospitals must meet the standards of infectious disease hospitals (10). Moreover, minimal building intervention is essential to ensure rapid project delivery; hence, the original infrastructure should be fully utilized (25).

① Electricity systems: The transformation of the power system should minimize the impact on the fire protection system of the original site. There should be a reliable high-power electricity supply system. Additionally, a backup power supply system and emergency lighting system are necessary (24). Nursing stations and medical office areas should be equipped with a certain number of sockets to facilitate the routine work of the medical staff. Furthermore, the sockets provided in the hospital bed area should meet the needs of patients to use low-power electrical equipment, such as mobile phones and lamps (21).

② Ventilation: The airflow should be blown from the clean area to the contaminated area (23); therefore, it is recommended to set up a mechanical ventilation system to control the airflow in the hospital (19). Besides, air purifiers can be used in contaminated and semi-contaminated zones to reduce the possible virus-laden aerosols (26).

③ Toilets: Medical staff and patients' toilets should be kept separate, and foam-blocked mobile toilets are preferred (22). Toilets should be built downwind, away from the dining areas and water points. All toilet feces must be strictly disinfected and subjected to concentrated harmless treatment under the requirements of the infectious disease hospital, wherein direct discharge is strictly prohibited (27).

④ Water supply: The centralized water supply system should be equipped with sterilization and disinfection facilities (28). Furthermore, the pumping house and hot water room should be set in a clean area. Each nursing group should set up a water supply point, and drinking water points for medical staff and patients should be kept separate (23, 29).

⑤ Sewage: Sewage from mobile cabin hospitals, including condensate water from air conditioners, should not be directly discharged, and temporary tanks for sewage treatment should be established (30). Additionally, an automatic monitoring system for water quality should be installed at treated sewage outlets to ensure that the discharged sewage meets the standards (31).

⑥ Fire protection: It is necessary to ensure that the automatic fire alarm system and fire facilities of the original building can be used normally (23). There should be at least two safety exits in different directions in the ward (19). Additionally, each medical staff member should be equipped with a firefighting self-rescue respirator (22).

⑦ Heating or cooling: It is not recommended to use centralized air conditioning to adjust the indoor temperature in order to prevent cross-infection. While split air conditioning can be used to cool down in summer, electric heating blankets and electric oil heaters can be used for heating in winter (19). Additionally, mobile cabin hospitals in Wuhan prepared quilts and down coats for each patient.

Architectural Layout

The layout of a mobile cabin hospital follows the standards of infectious disease hospitals, which are partitioned into three zones (contamination zone, semi-contamination zone, and clean zone) and two passages (staff passage and patient passage) (4). The contaminated zone refers to areas where patients reside and receive treatment, comprising the wards, treatment rooms, waste rooms, and places of activity. The clean zone includes the medical staff's dressing room, catering room, duty room, and warehouse. The semi-contaminated zone is the area between the clean and contaminated zones, comprising the medical staff's offices, nurse stations, medical equipment areas, and other areas that may be contaminated by patients (10). Each zone should be marked and isolated, and fixed routes must be set for the medical staff to enter and leave the contaminated zone (22). Partition materials shall be anti-inflammable with height of at least 1.8 meters (21, 24).

Functional Zoning

According to the medical functions, mobile cabin hospitals are mainly divided into the following sections (32, 33):

① Ward: It is the core area of a mobile cabin hospital, which is divided into different sections for male and female patients and further divided into the general area and key observation area according to whether the patients have underlying diseases. In the patient ward, beds are at least 1.2 m away from each other and equipped with hand sanitizer at the end of each bed (5). In case of double-row beds, a distance of at least 1.4 m is maintained between the ends of close beds (19, 21).

② Image testing area: This area is composed of multiple sets of imaging examination vehicles and various imaging techniques such as radiography, computed tomography, and ultrasonography are conducted.

③ Routine laboratory testing area: Routine laboratory inspection tasks, such as routine blood testing of patients, are performed in this area.

④ Virus nucleic acid detection area: It is composed of mobile P3 laboratories (34).

⑤ Intensive observation and treatment area: This area is equipped with oxygen cylinders, rescue medicines, and monitoring equipment to provide treatment and nursing for patients whose conditions worsen during hospitalization (22).

Management of Mobile Cabin Hospitals

Organizational Management

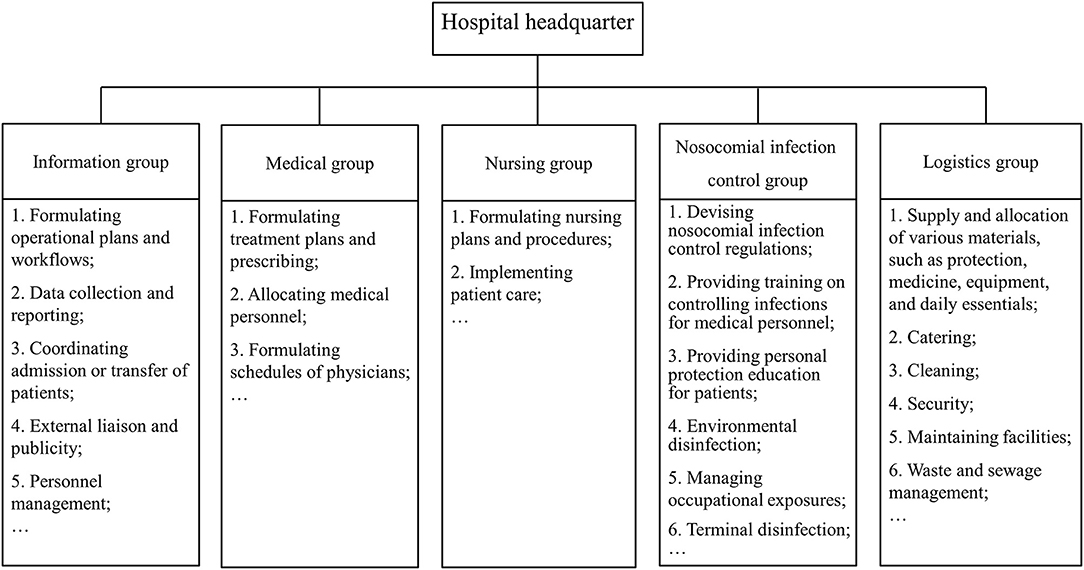

Clarifying each person's responsibilities and ensuring the stability of the management team are prerequisites for the effective operation of a mobile cabin hospital. Mobile cabin hospitals in Wuhan implement a management model led by the district government, operated by medical institutions, and coordinated by other relevant units such as electric power and water affairs departments (35, 36). The district government and medical institutions appoint professional management personnel to form the mobile cabin hospital headquarter (37), which consists of an information management group, medical group, nursing group, nosocomial infections control group, logistics group, and other departments (Figure 2). Each department has clearly defined responsibilities and division of labor. This flat organizational structure simplifies the vertical management levels and is suitable for the temporarily established management team of the mobile cabin hospital (38).

Management of Nosocomial Infections

Management of nosocomial infections is important to cut off the transmission route of COVID-19 and reduce cross-infection. A mobile cabin hospital should set up a nosocomial infections control team that conducts regular trainings to control hospital infections for all medical personnel and strengthens personal protection education for patients (39, 40). The training for medical personnel mainly includes zoning of the hospital, hand hygiene, wearing and unloading personal protective equipment (PPE), cleaning and disinfection knowledge, etc. Furthermore, the strategy of “three zones–two channels” should be strictly implemented, and the corresponding rules and regulations for controlling nosocomial infections should be formulated and followed (32, 41). Control measures for nosocomial infections mainly include personal protection, environmental health management, management of occupational exposure, management of discharged patients, and waste disposal.

① Personal protection: Before entering and leaving the hospital, the medical personnel should wash their hands and correctly wear and take off the PPE (42). All patients are required to wear masks, and their daily necessities are cleaned and disinfected (29). Moreover, all medical personnel and patients must undergo daily temperature monitoring (43).

② Environmental health management: Daily environmental disinfection of the air, ground, public facilities, and pollutants must be performed (43, 44). All the disinfection protocols conducted need to be recorded, including disinfection methods, disinfectant name, disinfectant concentration, disinfection frequency, and disinfection time (45).

③ Management of occupational exposure: Occupational exposure involves skin, mucosa, and respiratory exposure (42). A process for reporting and managing occupational exposure should be regulated, and the emergency management of risks, such as mask slipping or goggle loosening, should be standardized (40).

④ Management of discharged patients: All belongings should be terminally disinfected before the patient leaves the facility. Additionally, the clothing and daily necessities not taken away by the patients need to be treated as medical waste and handed over to the cleaners for centralized incineration (22).

⑤ Waste disposal: Mobile cabin hospitals produce a large amount of waste, such as medical waste, domestic waste, and patient excrement (feces, respiratory vomit, and other bodily secretions). All wastes generated in mobile cabin hospitals should be strictly managed (31). First, the collection, classification, packaging, sealing, marking, and treatment of waste should be regulated. Second, the temporary storage of waste, including storage time and disinfection methods, should be regulated. Third, the transshipment of waste, including transshipment time and route, vehicle selection, handover registration, and information sharing, should be clarified.

Information Technology Support

The information technology support not only improves the work efficiency of the medical staff, but also reduces the risk of cross-infection in hospitals (46). In the case of a pandemic, several aspects can be improved by using state-of-the-art technology (47, 48).

① The establishment of electronic medical record systems, including the electronic medical records module in the desktop hospital information system (HIS) and mobile electronic medical record system, can improve the quality of medical records (49–51).

② The pharmacy information system is used for maintaining records of the drug supply in and out of the warehouse, drug data collection, drug planning, prescription deployment, and expiration period management (52–58). It can automatically generate a drug catalog that enables pharmacists to query drug consumption and inventory quickly.

③ Through the HIS remote consultation system, the medical teams inside and outside the mobile cabin hospital can record the patient's vital signs and changes in disease conditions and perform timely adjustment of the treatment plans based on the patient's condition (59).

④ The application of high-technological products can reduce the workload of the medical personnel. For example, smart wristbands and watches can be used to monitor the patient's blood oxygen saturation, heart rate, and blood pressure and upload the data to the cloud platform, thus facilitating remote monitoring of patients (60). Notably, the mobile cabin hospitals of Jianghan developed an online application in which patients can request life support, healthcare, and other services through their mobile phones, and the medical staffs can accept these requests online and provide services to meet the needs of the patients (16).

Material Supply

The basis for the effective operation of mobile cabin hospitals is adequate material supplies, including medical equipment, medications, vaccines, PPE, and rapid diagnostic tests (61). The material supply of mobile cabin hospitals is coordinated and implemented by the government and medical institutions in China. To improve the effectiveness and timeliness of medical material support in China, a national information platform was built, which was mainly used to collect, analyze, monitor, and schedule the production, output, inventory, and transportation of various medical materials (62). The government mobilized manufacturing to ensure the supply chain of medical equipment and materials. Preferential financial and tax policies for supporting the prevention and control of the epidemic were issued, and the financial support for drug and vaccine research was increased (63). Furthermore, local government departments and many hospitals issued donation notices to the whole society, set up a lead group for donating materials, and gathered a large number of materials both from internal resources and abroad (64).

Policy Implications

Building Emergency Medical Rescue Team

To improve the emergency treatment function of medical institutions further, the construction of emergency medical rescue teams, especially personnel training to tackle public health emergencies, should be strengthened (65).

Establishing Emergency Material Reserve Mechanism

To avoid the shortage of medical supplies such as drugs and PPE, during public health emergencies, the state should quickly deploy and establish an emergency reserve system for medical materials (62). Under the unified organization of the health administrative department, each medical institution formulates a material list according to the actual needs and then procures and stores the required medical emergency materials.

Design and Construction of Large-Scale Public Venues

Converting large-scale public venues into mobile cabin hospitals is an important means of rapidly upgrading the healthcare system's capacity (10). Adaptability, convertibility, and expandability strategies should be included in the architectural design and construction planning of large-scale public buildings to allow for venues such as urban stadiums and exhibition centers to be converted into hospitals rapidly during major public health emergencies (25). For example, the interfaces of ventilation installation, sewage treatment systems and utilities should be reserved during architectural design and construction (4).

Strengthening the Financial Support of the Public Health System

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the importance of a strong national public health system. A high-grade public health system needs sufficient funds; therefore, developing countries need to invest more in the healthcare sector to manage urgent health needs, such as establishing testing laboratories, setting up special wards, and procuring medical supplies (63, 66).

Other Application Limitations to Be Concerned

The above experience has some limitations. First, this review aimed to summarize the emergency preparedness and management of the mobile cabin hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic; hence, our findings may contribute only to the control of the transmission of respiratory pathogens rather than all pathogens. In the management of patients with other diseases that spread through contact and / or enteric transmission, such as cholera, bubonic plague, and Ebola, the design of the mobile cabin hospital should be modified accordingly. For instance, the distance mentioned here between two beds is based on whether it is an airborne or droplet-transmitted pathogen. Second, mobile cabin hospitals can easily be erected in high-income countries. However, in low- and middle-income countries, relative inadequacy of resources and infrastructure may not meet the requirements for setting up these cabins. Therefore, the reconstruction and management of mobile cabin hospitals in these countries should be simplified to avoid cross-infection. For instance, electronic medical records may be replaced with paper records in countries that lack electronic information management systems.

Conclusion

Mobile cabin hospitals can be a key component of national public health responses to major epidemics, providing isolation and medical care for mild-to-moderate cases. Appropriate preparation and construction plans are necessary for converting large-scale public venues into mobile cabin hospitals, and a detailed management scheme is conducive for the normal operation of the hospital. This review may provide policymakers with useful information to upgrade the healthcare system's capacity by operating mobile cabin hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic and provide a valuable reference for preparedness for any future such outbreaks.

Author Contributions

CY, FS, and HL: conception and design and manuscript revision. FS, RL, YL, XL, and HW: literature research. FS and RL: first draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81773552, 82173626) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant numbers 2017YFC1200502, 2018YFC1315302).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.763723/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sun S, Xie Z, Yu K, Jiang B, Zheng S, Pan X. COVID-19 and healthcare system in China: challenges and progression for a sustainable future. Global Health. (2021) 17:14. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00665-9

2. Kuppalli K, Gala P, Cherabuddi K, Kalantri SP, Mohanan M, Mukherjee B, et al. India's COVID-19 crisis: a call for international action. Lancet. (2021) 397:2132–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01121-1

3. The Indian Express. Dr Anthony S Fauci on India's Covid Crisis: ‘Shut down the country for a few weeks…hang in there, take care of each other, we'll get to a normalș. (2021). Available online at: https://indianexpress.com/article/express-exclusive/indias-covid-crisis-anthony-s-fauci-coronavirus-death-7297380 (accessed May 1, 2021).

4. Chen S, Zhang Z, Yang J, Wang J, Zhai X, Bärnighausen T, et al. Fangcang shelter hospitals: a novel concept for responding to public health emergencies. Lancet. (2020) 395:1305–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30744-3

5. Sun C, Wu Q, Zhang C. Managing patients with COVID-19 infections: a first-hand experience from the Wuhan Mobile Cabin Hospital. Br J Gen Pract. (2020) 70:229–30. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X709529

6. Shi F, Wen H, Liu R, Bai J, Wang F, Mubarik S, et al. The comparison of epidemiological characteristics between confirmed and clinically diagnosed cases with COVID-19 during the early epidemic in Wuhan, China. Glob Health Res Policy. (2021) 6:18. doi: 10.1186/s41256-021-00200-8

7. Chen Z, He S, Li F, Yin J, Chen X. Mobile field hospitals, an effective way of dealing with COVID-19 in China: sharing our experience. Biosci Trends. (2020) 14:212–4. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01110

8. Wang KW, Gao J, Song XX, Huang J, Wang H, Wu XL, et al. Fangcang shelter hospitals are a one health approach for responding to the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. One Health. (2020) 10:100167. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100167

9. Zhu H, Wei L, Niu P. The novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Glob Health Res Policy. (2020) 5:6. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00135-6

10. Fang D, Pan S, Li Z, Yuan T, Jiang B, Gan D, et al. Large-scale public venues as medical emergency sites in disasters: lessons from COVID-19 and the use of Fangcang shelter hospitals in Wuhan, China. BMJ Glob Health. (2020) 5:e002815. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002815

11. Shang L, Xu J, Cao B. Fangcang shelter hospitals in COVID-19 pandemic: the practice and its significance. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2020) 26:976–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.038

12. Li J, Yuan P, Heffernan J, Zheng T, Ogden N, Sander B, et al. Fangcang shelter hospitals during the COVID-19 epidemic, Wuhan, China. Bull World Health Organ. (2020) 98:830–41. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.258152

13. Jiang H, Song P, Wang S, Yin S, Yin J, Zhu C, et al. Quantitative assessment of the effectiveness of joint measures led by Fangcang shelter hospitals in response to COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. BMC Infect Dis. (2021) 21:626. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06165-w

14. WHO. Prevention and Control of Outbreaks of Seasonal Influenza in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Review of the Evidence and Best-Practice Guidance. (2017). Available online at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/330225/LTCF-best-practice-guidance.pdf?ua=1 (accessed September 4, 2017).

15. Cepeda JA, Whitehouse T, Cooper B, Hails J, Jones K, Kwaku F, et al. Isolation of patients in single rooms or cohorts to reduce spread of MRSA in intensive-care units: prospective two-centre study. Lancet. (2005) 365:295–304. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17783-6

16. Zhang Y, Shi L, Cao Y, Chen H, Wang X, Sun G. Wuhan mobile cabin hospital: a critical health policy at a critical time in China. Medicine. (2021) 100:e24077. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024077

17. Fang CN, Liu FZ. Construction of Wuhan Makeshift Hospital and functional expansion of sports stadiums under COVID-19 crisis (in Chinese). J Wuhan Inst Phys Edu. (2020) 54:5–11. doi: 10.15930/j.cnki.wtxb.2020.12.001

18. Zhou F, Gao X, Li M, Zhang Y. Shelter hospital: glimmers of hope in treating coronavirus 2019. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2020) 14:e3–4. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.105

19. Science technology technology Industrialization Center of the Ministry of Housing Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China. Notice on Issuing the “Technical Guidelines for Construction and Operation of the Industrial Buildings Renovated to Mobile Cabin Hospitals (Trial)”. (2020). Available online at: http://www.chinahvac.com.cn/Article/Index/6035 (accessed February 25, 2020).

20. Liang H, Li HJ, Li ZY, Xu YC, Li BS, Liu Y, et al. Compilation interpretation of “Technical Guidelines for Construction and Operation of the Industrial Buildings Renovated to Mobile Cabin Hospitals (Trial)” (in Chinese). Constr Sci Technol. (2020) 403:27–30. doi: 10.16116/j.cnki.jskj.2020.06.006

21. Housing Housing Urban-Rural Development Department of Hubei Province China. Technical requirements for the Design and Conversion of Makeshift (FangCang) Hospitals. Revised ed. (2020). Available online at: https://zjt.hubei.gov.cn/zfxxgk/zc/zcjd/202004/t20200414_2222063.shtml (accessed March 30, 2020).

22. Housing Housing Urban-Rural Development Department of Shandong Province China. Guidelines for the Design of Shelter Temporary Emergency Medical Facilities. (2020). Available online at: http://zjt.shandong.gov.cn/art/2020/12/28/art_103756_10222432.html (accessed December 28, 2020).

23. Housing Housing Urban-Rural Development Department of Zhejiang Province China. Technical Guidelines for Shelter Temporary Hospitals. (2020). Available online at: http://jst.zj.gov.cn/art/2020/2/13/art_1229159347_48452710.html (accessed February 13, 2020).

24. Housing Housing Urban-Rural Development Department of Shandong Province China. Design Guideline for Emergency Transformation of Gymnasium Into Temporary Medical Center. (2020). Available online at: http://jsszfhcxjst.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2020/2/27/art_8639_8987348.html (accessed February 27, 2020).

25. Marinelli M. Emergency healthcare facilities: managing design in a post Covid-19 world. IEEE Eng Manage Rev. (2020) 48:65–71. doi: 10.1109/EMR.2020.3029850

26. Chen C, Zhao B. Makeshift hospitals for COVID-19 patients: where health-care workers and patients need sufficient ventilation for more protection. J Hosp Infect. (2020) 105:98–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.008

27. Zhang D, Ling H, Huang X, Li J, Li W, Yi C, et al. Potential spreading risks and disinfection challenges of medical wastewater by the presence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral RNA in septic tanks of Fangcang Hospital. Sci Total Environ. (2020) 741:140445. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140445

28. Zhou QY, Hong Y, Wan C. Key points of the water supply and drainage design for Mobile Cabin Hospital (in Chinese). Huazhong Arch. (2020) 38:123–25. doi: 10.13942/j.cnki.hzjz.2020.04.030

29. The The COVID-19 Emergency Response Key Places Protection and Disinfection Technology Team Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Health protection guideline of mobile cabin hospitals during COVID-19 outbreak (in Chinese). Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. (2020) 54:357–9. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20200217-00121

30. Chen Y, Zhou M, Hu L, Liu X, Zhuo L, Xie Q. Emergency reconstruction of large general hospital under the perspective of new COVID-19 prevention and control. Wien Klin Wochenschr. (2020) 132:677–84. doi: 10.1007/s00508-020-01695-w

31. Wang J, Shen J, Ye D, Yan X, Zhang Y, Yang W, et al. Disinfection technology of hospital wastes and wastewater: suggestions for disinfection strategy during coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in China. Environ Pollut. (2020) 262:114665. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114665

32. Xi XX, Wang H, Mao J, He XF, Liu M, Yu HX. Difficulties and coping strategies of safety management for inpatients with coronavirus disease 2019 at cabin hospital (in Chinese). Chin J Nurs. (2020) 55:53–55. doi: 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2020.S1.019

33. The National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Manual for Working in Fangcang Shelter Hospitals. 3rd ed. (2020). Available online at: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/va9vs4HuP8wRQM5fALQcrg (accessed February 22, 2020).

34. Yuan Y, Qiu T, Wang T, Zhou J, Ma Y, Liu X, et al. The application of Temporary Ark Hospitals in controlling COVID-19 spread: the experiences of one Temporary Ark Hospital, Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. (2020) 92:2019–26. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25947

35. Wang JJ, Zhou Q, Sun H, Yuan BC, Long HB. Fangcang shelter hospitals in Wuhan during the COVID-19 epidemic: practice of collaborative management (in Chinese). Chin J Med Mgt Sci. (2021) 11:50–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-7432.2021.02.010

36. Zhang YD, Ding N, Hu Y, Sun H, Fu XQ, Yu JH, et al. Exploration and analysis of the management mode of a cabin hospital during the outbreak of COVID-19 (in Chinese). Chin J Hosp Admin. (2020) 36:281–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112225-20200226-00320

37. Fu XQ, Sun H, Xin YJ, Sun Y, Xu XB, Shu Q, et al. Practice and thinking on medical management of cabin hospitals in emergency management of public health emergency: Taking Jianghan Cabin Hospital as an Example (in Chinese). Med Soc. (2020) 33:86–9. doi: 10.13723/j.yxysh.2020.05.018

38. Huang Q, Zeng W, Cai YH. Research on operation and management standardization of makeshift hospital in response to public health emergency (in Chinese). China Stand. (2020) 8:43–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-5944.2020.08.002

39. Zhou J, Yang Y, Huang L, Chen K, Zhang W, Xiong W. Practice and effect of physician – pharmacist - nurse cooperation mode in the prevention and control of nosocomial infection in Fangcang Hospitals (in Chinese). China Pharm. (2020) 29:40–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-4931.2020.09.011

40. Luo XB, Ling RJ, Ding YX, Wang YY. Evaluation of measures for prevention and control of health care associated infections in Wuhan Jiang'an Shelter Hospital during the outbreak of coronavirus disease-19 (in Chinese). Chin J Viral Dis. (2020) 10:284–8. doi: 10.16505/j.2095-0136.2020.0029

41. Luo XB, Ling RJ, Ding YX, Wang YY. Practice of nosocomial infection management in shelter hospital under COVID-19 pandemic (in Chinese). Chin J Soc Med. (2020) 37:465–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5625.2020.05.004

42. Yang Y, Wang H, Chen K, Zhou J, Deng S, Wang Y. Shelter hospital mode: how do we prevent COVID-19 hospital-acquired infection? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. (2020) 41:872–3. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.97

43. Wu WJ, He LH, Liu B, Wang L, Lei H, Xiang Z. Nosocomial infection control strategy in cabin hospitals during the epidemic of COVID-19 (in Chinese). Chin J Hosp Admin. (2020) 36:320–3. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112225-20200301-00418

44. Zhang M, Wang L, Yu S, Sun G, Lei H, Wu W. Status of occupational protection in the COVID-19 Fangcang Shelter Hospital in Wuhan, China. Emerg Microbes Infect. (2020) 9:1835–42. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1803145

45. Wang JQ, Liu XL, Duan HY, Chen XM, Qian L, Lyu XF, et al. Disinfection and protective measures for makeshift hospitals. Biomed Environ Sci. (2020) 33:940–2. doi: 10.3967/bes2020.129

46. Liu P, Zhang H, Long X, Wang W, Zhan D, Meng X, et al. Management of COVID-19 patients in Fangcang shelter hospital: clinical practice and effectiveness analysis. Clin Respir J. (2021) 15:280–6. doi: 10.1111/crj.13293

47. He Q, Xiao H, Li HM, Zhang BB, Li CW, Yuan FJ, et al. Practice in information technology support for Fangcang Shelter Hospital during COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Med Syst. (2021) 45:42. doi: 10.1007/s10916-021-01721-y

48. Han YJ. Study on smart shelter hospital mode in response to public health emergency (in Chinese). China Emergency Rescue. (2021) 3:40–4. doi: 10.19384/j.cnki.cn11-5524/p.2021.03.009

49. Yu SS, Xiao H, Li HM. Design and practice of informatization of mobile cabin hospitals in COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control (in Chinese). J Med Inf. (2021) 42:66–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-6036.2021.02.014

50. Liu J, Zhang XY, Deng L, Zhang XL, Zhang LL, He Q, et al. The effect of health service support of the informationized mobile field hospital in the prevention and control of COVID-19 (in Chinese). China Digital Med. (2020) 15:12–4+33. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-7571.2020.09.003

51. Zhou B, Wu Q, Zhao X, Zhang W, Wu W, Guo Z. Construction of 5G all-wireless network and information system for cabin hospitals. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2020) 27:934–8. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa045

52. Hua X, Gu M, Zeng F, Hu H, Zhou T, Zhang Y, et al. Pharmacy administration and pharmaceutical care practice in a module hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Am Pharm Assoc. (2020) 60:431–8.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.04.006

53. Meng L, Qiu F, Sun S. Providing pharmacy services at cabin hospitals at the coronavirus epicenter in China. Int J Clin Pharm. (2020) 42:305–8. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01020-5

54. Zhang BB, Li CW, Xiao H. Design of the information system of the cabin hospital under COVID-19 (in Chinese). China Digital Med. (2020) 15:11–3+57.

55. Hua XL, Gu M, Luo L, Zeng F, Zhang Y, Shi C. The application of “Zero Contact” Informationized Pharmaceutical Service in the Prevention and Control of COVID-19 in Hospitals (in Chinese). China Digital Med. (2020) 15:51–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-7571.2020.05.018

56. Chen SD, Tang J, Ye Q, Liu D. Practice and discussion of non-contact drug dispensing pattern in Square Cabin Hospital (in Chinese). Her Med. (2020) 39:940–2. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1004-0781.2020.07.011

57. Su D, Ma L, Huang L, Chen K, Wang YR, Zhang EJ, et al. Construction of pharmaceutical care system for public health emergencies based on the pharmaceutical administration in Wuhan Fangcang Hospitals (in Chinese). China Pharm. (2020) 29:16–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-4931.2020.07.004

58. Gong WJ, Zhou T, Xu CF, Xu JQ, Liu YH, Han Y, et al. The practice and discussion of online pharmaceutical service mode in mobile cabin hospital (in Chinese). Chin J Hosp Pharm. (2020) 40:876–9. doi: 10.13286/j.1001-5213.2020.08.08

59. Yao G, Zhang XX, Wang HM, Li J, Tian J, Wang L. Practice and thinking of the informationized cabin hospitals during COVID-19 epidemic (in Chinese). Chin J Hosp Admin. (2020) 36:334–6. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112225-20200218-00200

60. Ding X, Clifton D, Ji N, Lovell NH, Bonato P, Chen W, et al. Wearable sensing and telehealth technology with potential applications in the coronavirus pandemic. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. (2020) 14:48–70. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2020.2992838

61. Zhang Y, Ding Q, Liu JB. Performance evaluation of emergency logistics capability for public health emergencies: perspective of COVID-19. Int J Logist Res App. (2021) 4:1914566. doi: 10.1080/13675567.2021.1914566

62. Cao Y, Shan J, Gong Z, Kuang J, Gao Y. Status and challenges of public health emergency management in China related to COVID-19. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:250. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00250

63. Xing C, Zhang R. COVID-19 in China: responses, challenges and implications for the health system. Healthcare. (2021) 9:82. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9010082

64. Li YR, Chandra Y, Kapucu N. Crisis coordination and the role of social media in response to COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Am Rev Public Adm. (2020) 50:698–705. doi: 10.1177/0275074020942105

65. Zhang HL, Liu JF, Zhao J, Xiang Z, Zhang JY, Zhai XH, et al. Thinking about the safety prevention and control in the module hospital (in Chinese). Chin Health Qual Manage. (2021) 28:40–3. doi: 10.13912/j.cnki.chqm.2021.28.5.12

Keywords: mobile cabin hospital, Fangcang shelter hospital, management, COVID-19, China

Citation: Shi F, Li H, Liu R, Liu Y, Liu X, Wen H and Yu C (2022) Emergency Preparedness and Management of Mobile Cabin Hospitals in China During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 9:763723. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.763723

Received: 24 August 2021; Accepted: 29 November 2021;

Published: 03 January 2022.

Edited by:

Shi Zhao, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaReviewed by:

Abdulrazaq Habib, Bayero University Kano, NigeriaLefei Han, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China

Copyright © 2022 Shi, Li, Liu, Liu, Liu, Wen and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chuanhua Yu, yuchua@whu.edu.cn

Fang Shi

Fang Shi Hao Li2

Hao Li2 Rui Liu

Rui Liu Chuanhua Yu

Chuanhua Yu