Western Centric Medicine for Covid-19 and Its Contradictions: Can African Alternate Solutions Be the Cure?

- Institute of Pan African Thought and Conversation (IPATC), University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

The full impact of COVID-19 is yet to be fully understood, and while there are many unknowns, the rapid and continued reliance on the social media cannot be denied. Some Global Economy and World Health Organisations have discouraged the usage of traditional medicine for COVID-19 treatment. However, some African states such as Tanzania, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea Conakry, and Togo have engaged with formal researchers to see if traditional medicine can treat COVID-19. Nevertheless, there is still a lot of hesitancy amongst African populations in getting vaccinated. The paper conceptualises the criticism of Western-centric medicine and investigates the promotion of alternate approaches in the African economy. The article situates the study context by exploring the African economy's socio-politics and public health governance. It investigates explicitly African states responses to conventional treatment by analysing the role of traditional medicine and its efficacy as well as the possible effects on the continent. The methodological framework engaged a review approach relying heavily on reputable secondary sources from government publications, journal articles, books and publications from professional bodies and institutional search engines. The data was analysed in themes supporting the study aim's and objectives. The paper concludes that Africa could consolidate the readily available knowledge and give opportunities to traditional medical therapies that are cheap, convenient and safe for public health, especially for COVID-19 supposedly cure.

Introduction

The advent of COVID-19 as a new pandemic in the global economy has led the public to seek an alternative health cure. Since its inception, the politics and belief systems on its treatment made people, especially in the African continent, go on their ways in finding its supposed “cure.” The full impact of COVID-19 is yet to be fully understood, and while there are many unknowns, the rapid and continued reliance on social media platforms as a source of information (facebook, twitter, youtube) cannot be denied. Thus, Obi-Ani et al. (2020, p. 2) argue that whilst social media is tagged with divulging information that is credible as well as dubious in “recent times, as the pandemic encroaches on and emasculates world activities, social media platforms have been utilized as an information outlet to citizens.” Moreover, it has not only become an uncontetable information tool for the populace but also it “has become a pivotal communication tool for governments, organisations, and universities to disseminate crucial information to the public” (Tsao et al., 2021, p. 175).

For instance, Menezes et al. (2021) based on a survey conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa argue that vaccine hesitancy in this part of the world is highly attributrd to the misconstruded information and conspiracy theories that is widely spread on social media about the efficacy of the vaccine. Bsased on this argument, one can therefore argue Africans would rather trust in their locally made products that is prepared by their herbal practitioners with feasible results than some vaccine that is produced by someone they do not even know. For instance, the high local demand for Archbishop Samuel Kleda of the Douala diocese plant-based medicine “Elixir Covid” and “Adsak Covid” can be attributed to the positive palpable results it had on the people (Reuters., 2020).

Some Global Economic institutions and the World Health Organisation have discouraged the usage of traditional medicine for COVID-19 treatment. However, some African states such as Tanzania, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea Conakry and Togo have engaged with formal researchers to see if traditional medicine can treat COVID-19.

Nevertheless, there is still a lot of hesitancy amongst African populations in getting vaccinated. Many critics have argued the possibility of alternative traditional medicines as a better option for COVID-19 cure than Western-centric medicine for the global pandemic. Due to the limited availability and access to the supposed western-centric medicine for vaccination, Africans embraced traditional medicines, which were more available and believed to increase safety. The emergence of conventional medicine, also referred to as “Ethnomedicine,” has been considered to alleviate and cure COVID-19 and its symptoms. Many resaerchers in herbal medicine believe that the low impact of COVID-19 on the African communities is because of the local herbal remedies. Even though there is no formal approval on ethnomedicine or traditional medicine by the regulatory bodies such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the African Medicines Agency (AMA) many promising results emerged on applying for conventional medicine in managing COVID-19 in the continent (WHO, 2021a). The paper conceptualises the criticism of Western-centric medicine and investigates the promotion of alternate approaches in the African economy. It is in this context that the research question that guides this paper poses the question Can Traditional medicine be seen as an alternate approach to Western-Centric medicine? The article situates the study context by exploring the African economy's socio-politics and public health governance. It investigates explicitly African states responses to conventional treatment by analysing the role of traditional medicine, what are the efficacies of these therapeutic approaches', and the possible outcomes on the continent. Finally, the paper will employ secondary data to present a detailed literature review to evaluate current traditional medicine's impact and future treatment of COVID-19.

The paper is divided into five sections, and the first part discusses the emergence of COVID-19 and Western Centric Medicine. The second section debates the theory of public health governance to explain the African state responses to the global pandemic in general and conventional treatments. The third part describes the promotion of ethnomedicine or alternate approaches in the African economy and its efficacy and possible effects. The fourth section analyses the findings on literature for alternate approaches in Africa. The last section concludes that Africa could consolidate the readily available knowledge and give opportunities to traditional medical therapies that are cheap, convenient and safe for public health, especially for Covid-19 supposedly cure. The methodological framework engaged a review approach relying heavily on reputable secondary sources from government publications, journal articles, books and publications from professional bodies and institutional search engines. The data was analysed in themes supporting the study aim's and objectives. The paper concludes that Africa could consolidate the readily available knowledge and give opportunities to traditional medical therapies that are cheap, convenient and safe for public health, especially for Covid-19 supposedly cure.

Conceptual Framework- The Dependency Theory

“The Time Is Now to Wither From the Dependency of Africa on the West'

The debates among the liberal reformers (Prebisch), the Marxists (Andre Gunder Frank), and the world systems theorist (Wallerstein) were vigorous and intellectually quite challenging. There are still points of serious divergences among the various strains of dependency theorists and it is a mistake to think that there is only one unified theory of dependency. Nonetheless, there are some fundamental propositions which seem to cut across the analyses of most dependency theorists (Ferraro, 1996).

Dependency has been defined as an explanation of the economic development of a state in terms of the external influences (political, economic, and cultural) on national development policies (Sunkel, 1969). Theotonio Dos Santos underscores the historical dimension of the dependency relationships in his definition when he wrote:

Dependency is...an historical condition which shapes a certain structure of the world economy such that it favours some countries to the detriment of others and limits the development possibilities of the subordinate economics...a situation in which the economy of a certain group of countries is conditioned by the development and expansion of another economy, to which their own is subjected (Santos, 1970).

Trade relations are based on monopolistic control of the market, which leads to the transfer of surplus generated in the dependent countries to the dominant countries; financial relations are, from the viewpoint of the dominant powers, based on loans and the export of capital, which permit them to receive interest and profits; thus increasing their domestic surplus and strengthening their control over the economies of the other countries (Santos, 1970).

When one examines these definitions, there are three common features that stand out clearly that is shared by most dependency theorists. First, dependency is characterized by an international system that comprises of two sets of states, described as dominant/dependent, center/periphery or metropolitan/satellite. The dominant states are the advanced industrial nations in the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The dependent states are those states of Latin America, Asia, and most importantly Africa in the case of this paper.

The dependent states are states with low per capita gross national product (GNPs) and that heavily rely on the export of a single commodity for foreign exchange earnings, and the importation of variety of goods from the western developed dominant states.

Second, both definitions have in common the assumption that external forces are of singular importance to the economic activities within the dependent states. These external forces include multinational corporations, international commodity markets, foreign assistance, communications, and any other means by which the advanced industrialized countries can represent their economic interests abroad.

Third, the definitions of dependency all indicate that the relations between dominant and dependent states are dynamic because the interactions between the two sets of states tend to not only reinforce but also intensify the unequal patterns. In simplar terms, dependency theory attempts to explain the present underdeveloped state of many nations in the world by examining the patterns of interactions among nations and by arguing that inequality among nations is an intrinsic part of those interactions. Simply put, dependency theory attempts to explain the present underdeveloped state of many nations in the world by examining the patterns of interactions among nations and by arguing that inequality among nations is an intrinsic part of those interactions (Uwazie et al., 2015, p. 29). Emeh (2013, p. 116) puts it succinctly in these words “dependency implies a situation in which a particular country or region relies on another for support, ‘survival’ and growth.”

Based on the above explanations advanced on the dependency theory, one can therefore make the case that the reliance of Africa on the west in this era of the Covid pandemic for vaccines, medical appliances and loans is a clear demonstration that Africa is still much dependent on the west. This statement is supported by Patrick Bond who notes that in the 1980s and 1990s HIV/AIDS drugs were priced at 15,000 USD per person per year and African states highly depended on the North for medication. This became an avenue through which financial resources were syphoned (2017, p. 68).

In addition, Africa's dependency is coined to what Emeh (2013, p. 120) describes as elite complicity and to what the authors refer to as a dominantly predatory elite class. This is a situation whereby those in authority because of what they stand to gain have failed to come up with alternatives to counter what is proposed by the west and donor countries especially in the era of the Covid pandemic. This is further enforced by the agreements that have been entered into between the rich capitalist of Third World countries represented by the elite comprador class and the rich core capitalist. For instance the Financial Times notes that “across Africa, officials are being swept up in investigations into whether they used their positions to siphon funds intended to tackle the pandemic” (Financial Times, 2021). This is but evident that whilst the African elite comprador is completely absent in providing and encouraging alternatives such as making use of our natural resources to curb and tackle pandemics, they are always ready to accept loans at high interest rates knowing fully well that these will be diverted in to their private accounts. In Cameroon for instance in what has been referred to as the covidgate, right groups, opposition parties and the local media has called on the government to publish its findings after most of a $335 million loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) allocated for Covid could not be accounted for Kindzeka (2021). This call has further been amplified by a group of leading women in Cameroon who have requested and urged the IMF to halt talks on a proposed new loan until more clarity is gotten as to how the previous funds were spent (Hoije and Lukong, 2021).

The Emergence of Covid-19 and Western Centric Medicine

Regardless of the several attempts to alleviate and mitigate the spread and mortalities associated with COVID-19, the virus continues to spread its tentacles within the humanity and global economy. The result led to more deaths, increased poverty, and declining and collapsed economy. Most developed economies like Europe and America have encouraged and relied on western-centric medicine, motivating people to vaccinate. However, South-East Asia and China, where the COVID-19 pandemic originated, have shown the successful outcomes of integrating Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) with western-centric medicines in COVID-19 management (Gao et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020). Vaccination has played a role in eradicating and reducing diseases and infections that have plagued the world. The public health achievements have the 1900s on infectious diseases such as poliomyelitis, measles, rubella, tetanus, Ebola, not to mention a few. Despite the extraordinary achievements, the global community still expresses great concern regarding the safety and health of the mass population (Dzimanarira et al., 2021). The international competition on Covid-19 vaccines became a competitive debate on securing supplies for developing economies.

Currently, the United Nations report only projects 75% Covid-19 vaccines administered to just ten countries. Most poorer countries are struggling to secure supplies. As a result, higher-income countries representing only 16% of the world's population have already purchased more than 60% of the Covid-19 vaccination doses. Countries such as Canada and the United States of America have purchased vaccines for their entire population, but African Union has only bought 38% of its total population. Most African countries beneficiaries have received donations from China, Russia, India and United Arab Emirate (UAE) countries or the African countries ordered directly from the international manufacturing institutions (Dzimanarira et al., 2021). In Africa, only five countries such as Mauritius, South Africa, Seychelles, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe have implemented Covid-19 vaccination roll-outs specifically focused on the health and frontline workers, high-risk groups and its population. Yet, they cannot motivate citizens to get the vaccinations due to the reasoned conflicts behind its application. Other African countries are still lacking in this category. The African community relies on the COVAX facility, a global initiative established in April 2020 by the World Health Organisation, European Commission and France as a global response strategy to the Covid-19 Strategy. Even though COVAX aim to distribute equally the Covid-19 vaccine across the global economy, few African countries are recipients of the Covid-19 supplies to date (BusinessTech., 2021).

For instance, the South African state ordered a million doses of the AstraZeneca/Oxford COVID-19 vaccine, which was eventually suspended due to the global report showing the vaccine's low efficacy on the 501Y.V2 variant of the coronavirus (Roets, 2021). By February 17, 2021, the South African government started a new Covid-19 vaccine roll-out of Johnson and Johnson with an initial 80,000 doses on the healthcare professionals, which has been effective and gradually on the citizens. However, most African states are still plagued with the impact of the COVID-19 virus with mortality daily. Currently, some African countries are preparing for fourth and fifth wave-like South Africa. Even so, most people live in the uncertainty of the vaccine. Many religious and individual groups have made negative outbursts and encouraged most people not to take the vaccine as it represents the end of the world sign. Vaccine uncertainty is a primary impediment to vaccine acceptance and the achievement of people's immunity, which is mandatory to protect the marginalised populations in the country. The country needs to ensure effective and protected vaccine to be delivered immediately and broadly to the nation as soon as it is available to reduce morbidity and mortality from COVID-19. However, the mere accessibility of a vaccine is not enough to secure extensive immunological security; the immunisation must be accepted by the health sector and the general masses in the country. African government's strategic efforts to deal with the disease and vaccination roll-out in responding to COVID-19 remains a significant challenge.

According to literature, China and co Asian countries have had a robust age-long traditional medicine system that embraced traditional medicine with western medicine. The evidence was displayed to combat the first outbreak of the SARS-CoV in Guangdong, China, in 2002, which ended the pandemic without spreading to the global economy. Many Chinese traditional medicines such as “San Ren Tang,” “Yin Qiao San,” “Gan Lu Xiao Du Dan,” and “Ma Qing Ying Tang” represent a polyherbal formulation containing many indigenous plants to treat the pandemic outbreak. Evidence also documented, Hong Kong acknowledging the use of “Sang Ju Yin” and “Yu Ping Feng San,” “Isatis tinctoria L. (Brassicaceae)” and “Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi (Lamiaceae),” for prophylactic use among health workers against SARS-CoV infection (Hensel et al., 2020; Lou et al., 2020). The successful outcome of the traditional remedies at the first outbreak led to the immediate authorisation of integrating traditional medicine with western medicine to cure SARS-CoV2 (Gao et al., 2020).

The African population shares the standard belief systems like the Chinese government, partly because of the African socio-economic and socio-cultural endowments. However, more than 80–90 per cent of the economy embraces herbal medicines, also referred to as “phytomedicines” or phytotherapy (mainly plant-based), for their primary healthcare (Elujoba et al., 2005). The African Union also attest to this by stating that herbal-based traditional medicines or phytomedicines plays a crucial role in disease management in Africa and are widely available for use as alternative medicines. As a result, global institutions such as World Health Organisation (WHO) have solicited African member states to adopt traditional medicine since the institution has witnessed the importance of conventional medicine with identified knowledgeable indigenous practitioners (Lone and Ahmad, 2020). Furthermore, as indicated earlier, many African communities resolved to use traditional medicines during the Covid outbreak due to their availability and affordability (WHO, 2020).

Especially since the evidence presented by the African Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) indicated that the African continent was the last to be hit by the viral pandemic and least affected continent. As of July 21, 2020, the mortality rate in Africa was 2.1%, which was less than half of the reported global mortality of 5% rate. African communities have engaged with the African medicinal plants for COVID-19 management, malaria treatment, and other known diseases. The pan-African communities often co-administer herbal remedies alone or combined with western medicines as adjuvants. Many of these plant-based medicines have since been informally repurposed by various users for COVID-19 prevention symptomatic management as simple home remedies. The African states have the evidence on the impact of the widely embraced traditional medicine and alternative approaches for the prevention, management and treatment of COVID-19. The next session reviews the different documentation of African medicinal plants and their therapeutic potentials in preventing and managing COVID-19.

Public Health Governance and African State Responses To The Global Pandemic In General and Conventional Treatments

Public Health Governance has become an increasing context of debate within the global economy, especially in Africa (Van Ryneveld et al., 2020). It defines the collective authority or decision making made by the government or political leaders in achieving goals and objectives of health policies to render health care services to the citizen's Van Ryneveld et al., 2020). Furthermore, Public health governance entails a political process that aims to meet a country's healthcare demands, including maintaining policy development within the health sector. In addition, public health governance also addresses the regulation of the behaviour of health care practitioners and providers and effective collaboration between the private sectors and other stakeholders (Singh, 2020). Since governance relates to the exercise of power and authority on the issues of socio-political and economic leadership in any state, public health governance explains the concept of health financialisation and the quality-of-service delivery on health care. Most importantly, effective reforms and the development of health financialisation ensure quality healthcare for all (Singh, 2020).

All actors and stakeholders within the health system are expected to act and interact in a particular manner shaped as leadership and management. Hence, the health practitioners' roles are designed to steer and establish the system to achieve the government's goals (Van Ryneveld et al., 2020).

There was an increase in shortage of health practitioners within the health systems due to work overload during the global pandemic and the mortality rate that occurred during the pandemic. Most health practitioners are burnout, leading to increased absenteeism and poor health services, especially in the public sector (Gostin et al., 2020). Most African governments have found themselves in the space of making important decisions to recruit foreign and retired health practitioners to assist with the stress and pressure placed on the system. The impact of COVID-19 on the health practitioners also led to fear and frustration within the sector due to deaths of colleagues and increasing mortality rate amongst the patients (Gostin et al., 2020).

In all the stressful events, it is the responsibility of the government and the health department to seek and support its employees by providing resources, communication, and reinforcements for quality provision of service to the patients (Singh, 2020). However, the health system's governance lacks transparency and development due to corruption. The impact of crime within the health system has plagued most African states causing financial constraints and inaccessibility of the poor in health care services. In addition, the misuse of available health resources and vaccinations supplied to each health system has also led to inefficient public expenditure, which worsens the health outcomes of most African communities (Van Ryneveld et al., 2020).

The outbreak of COVID-19 has once more brought to light the struggle to contend with unprecedented shocks arising from the novel viruses and the challenge that is faced by the global health systems in dealing with them (Gebremeskel et al., 2021). However, in the case of Africa, reports from the United Nation Millennium Development Goals (2015) millennium development goals attainment stipulates that Africa's fragile Health systems continue to demonstrate high levels of attention in response to the effects of health emergencies and pandemics. Therefore, this has promoted the need for African governments to develop resilient and robust health systems that can withstand the shocks that come with novel pandemics such as COVID-19.

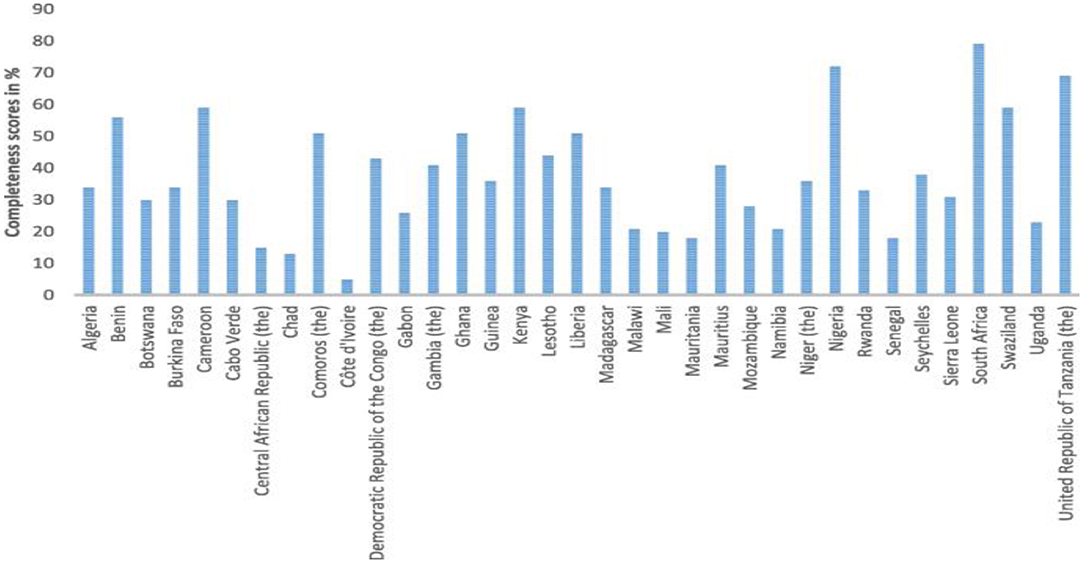

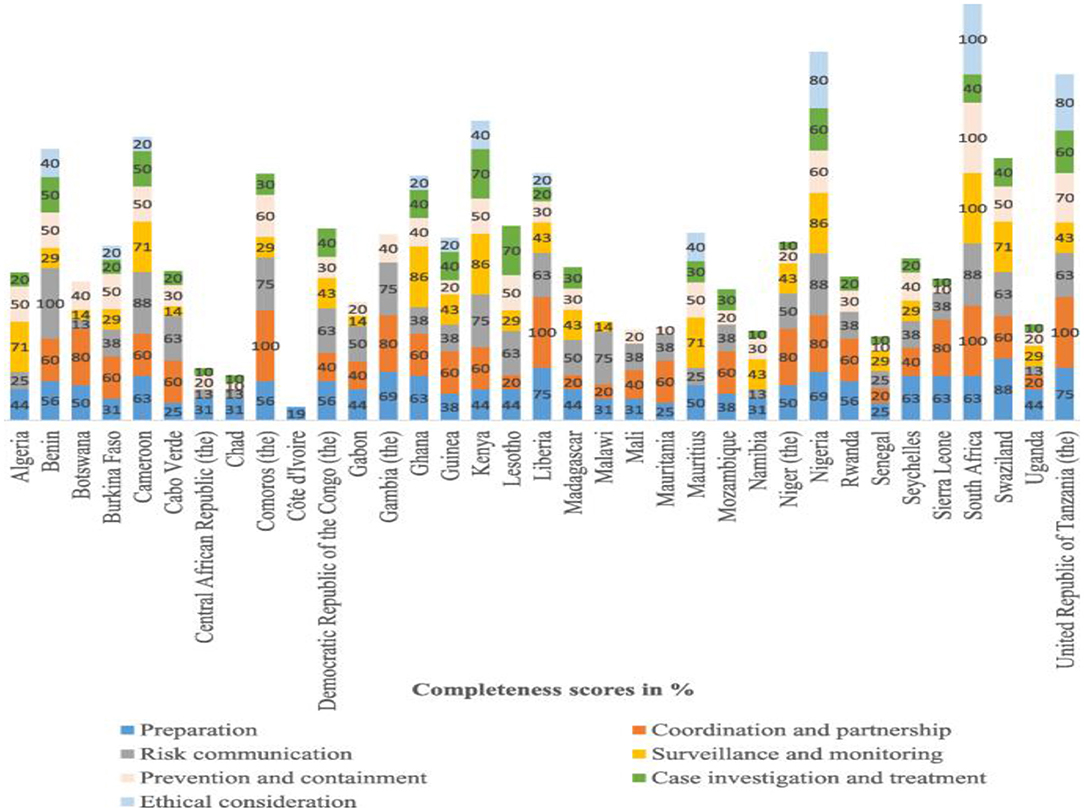

When one examines the aftermath of recent year's pandemics and epidemics in Africa, such as the H1N1 pandemic, the Ebola virus, SARS, and MERS, the question of preparedness and how Africa responds to global pandemics is an area of deep concern. Recent studies conducted in 2018 evaluated the calibre of country preparedness within the WHO African region. Out of 47 countries (of all 54 countries in Africa), 35 national pandemic preparedness plans were evaluated. Results found that readiness in South Africa was high at 79%, while Cote d'Ivoire only managed 5%. Across the 35 assessed countries, the combined score for pandemic plan completeness was 36%. The overall assessment indicated inadequate pandemic preparedness plans on the African continent (Sambala et al., 2018) (See Figures 1, 2 below).

Figure 1. Composite scores of preparedness plans by country. Source: Sambala et al. (2018).

Figure 2. Completeness of the preparedness plans of countries by category. Source: Sambala et al. (2018).

On average, risk communication and preparation was 48%, with coordination and partnership having the highest score (49%). Prevention and containment was 35%, while surveillance and monitoring scored 34% (Figure 2). Case investigation and treatment reported 25%, and ethical consideration was the lowest among 35 African countries at 14% (Badu et al., 2020, p. 7).

Apart from the linked problems and immediate pandemic control and prevention, other inadequacies faced by Africa's health systems include poor coordination, management, and leadership. Other factors include inadequate human resources and insufficient budget allocations for health, the lack of funds toward medical research and education, deplorable state of health amenities, poverty arising from unemployment/under-employment, lack of basic social amenities, and poor leadership/governance (Oleribe et al., 2019; Adesina, 2020; Nkengasong and Mankoula, 2020). Therefore, there is an urgent need to strengthen public health infrastructure and capabilities, as well as multi-sectoral coordination, human capacity, laboratory testing and surveillance systems in the aftermath of COVID-19 (Gilbert et al., 2020).

The Promotion of Ethnomedicine As An Alternative Approach In The African Economy and Its Efficacy And Possible Outcomes

The dire need to ensure that African health systems are more robust, resilient, and preparing for future outbreaks, has made Africa search for alternatives. The promotion of western-centric medicine has raised a question of the various options available in the global economy, especially in Africa. Advocacy and self-reliance of ethnomedicine in African communities' have also increased the curiosity of several individuals if the alternatives can be promoted as an alternative approach. Several alternative approaches to treating COVID-19 variants have emerged in different parts of the continent, with the western world is turning a blind eye to the resultant effects. We should understand that the outbreak of COVID-19 brought to bear a litany of dissonances as western pharmaceuticals, alongside their governments, grappled with which vaccine would be first in the market and which drug would act as a cure. For instance, approval ratings for vaccines such as Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, AstraZeneca and Johnson and Johnson have been widely endorsed by the WHO (2021b). Several governments have also approved these vaccines in the global economy and civil societies organisations and NGOs based on the results after high scrutiny and tests conducted on the vaccines. The argument we are making here is that these vaccines did not get the needed endorsement by night; it took financial investments from their governments and rigorous tasting to arrive at such results.

However, this did not deter Africa's efforts to tap into their local reservoir of herbs to assist their various communities in the fight against the novel pandemic. In this context, researchers from multiple regions around the continent have been working tirelessly to showcase that Africa is endowed with mineral resources and home to herbal medicinal plants that can be used to good effect if supported financially. For instance, in the Southern African region, a country like Lesotho has been recognised as stepping up in the fight against COVID-19. In 2020 the National University of Lesotho (NUL), through a team of researchers, came up with a COVID-19 potential treatment proven as a future drug after having undergone several trials in South Africa (Government of Lesotho, 2020).

According to the latter, the compound drug was taken to the “Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) Pretoria in South Africa. At the centre, it was revealed that the compound drug is active or effective against the two Coronaviruses tested, namely SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV as well as for toxicity and therapeutic index” (Government of Lesotho, 2020). Moreover, based on the strides made by the said product, Dr. Lerato has stated that the research has been hindered due to lack of finance and that she even fears for her life given the potential of the drug. In addition, she stated that she had received threats from people saying that the initiative was not hers (SABC News, 2021). However, one can argue that these threats per say are not because at any given time the latter had claimed that the initiative was solely her's. As such these threats might be engineered by some foreign agencies considering that the therapy poses a potential threat to the global pharmaceutical network of capitalism, which has its local resonances; hence the necessity of rising to the security challenge by African nation states.

Cameroon, a growing number of herbalists, traditional healers, and medical practitioners have been coming up with proposed cures for the deadly virus since the outbreak of the novel pandemic (Reuters., 2020). For example, Archbishop Samuel Kleda of the Douala diocese, who has practised herbal medicine for over thirty years, came up with two products, namely “Elixir Covid” and “Adsak Covid” (Reuters., 2020). The plant-based remedies were given free to those who tested positive for respiratory disease. As a result, as at the time of the Covid-19 declaration, the archbishop stated that more than 3,000 COVID-19 patients had been cured with the remedies (Reuters., 2020). Moreover, in line with further instructions from the head of state, President Paul Biya's excellency also encouraged all efforts to develop an endogenous treatment for COVID-19.

Furthermore, Archbishop Samuel Kleda was invited by Prime minister Dr. Joseph Dion Ngute to discuss the work that has been done and to see how the product can be made available to a larger audience (Tih, 2020). Currently, reports from the Catholic church stated that more than “9,071 patients have benefited from the treatment in Cameroon and abroad (Tih, 2020). In addition, individuals from developed and other local economies such as the United States, France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Zambia, and Gabon” have also benefited (Tih, 2020). Furthermore, in November 2020, the archbishop was honoured with a special trophy in recognition of his fight against Covid-19 “Prix Special de L'excellence Sanitaire Mondiale” (Cameroon Tribune, 2020). After receiving the prize, the archbishop said he was happy but further highlighted that he was delighted that many recovered their health after being administered with his medicine base plant. This was compelling evidence that Africans could still treat themselves with natural plants and ethnomedicine recognised as part of an alternative approach to medicine.

Cameroon's other discoveries include Dr. Jean Eddy Azombo, based in Yaounde. He discovered Fagaricine, which is also used for treating the coronavirus. He is the Africa Representative of Epsilon Santé Internationale, an international health organisation that runs medical laboratories (Ndukong, 2020). ‘Fagaricine’, which received some initial approval 4 years ago and is currently distributed in local pharmacies, was first initiated by Prof. Bruno Eto, Chairman of Epsilon Santé Internationale. It was then used to boost people living with HIV/AIDS (Ndukong, 2020).

Furthermore, Marlyse Paule Mbezele Ndi Samba, in partnership with Peyou, a PhD holder in Biochemistry and Biophysics from Washington State University in the USA, developed and discovered local Africa herbs that serve as a cure for the deadly virus (Ndukong, 2020). Another research on alternative medicine in Cameroun is Dr. Marlys, a lecturer in the Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences of the University of Yaounde, with a product called “Ngul Be Tara” or “the power of ancestors.” She opines that her product can be preventive and curative against coronavirus (Ndukong, 2020). However, the efficacy of this claim is yet to be proven and tested.

Another example that cannot be isolated was the research and sample presented in Madagascar. On April 22, 2020, President Andry Rajoelina publicly launched and drank Madagascar's COVID Organics, the Coronavirus preventive/curative potion (Nordling, 2020). The therapy was developed by the Malagasy Institute of Applied Research (IMRA). Its chief ingredient is sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua), a plant of Asian origin that gave rise to the antimalarial drug artemisinin (Nordling, 2020). Despite the reservations made concerning the organic drink by World Health Organization (WHO), the point of contention here is that various international institutions highlighted very little to assist the Malgache government in carrying out other trials and studies to establish its efficacy.

Professor Fru Asanji Fobuzshi Angwafo, Director General of the Gynaeco-Obstetric and Pediatric Hospital in Yaounde, Cameroon, underscores that “budding scientific research, in the realm of traditional pharmacopoeia, has proffered endogenous responses, bringing a glimmer of hope to Africans concerning the COVID-19 pandemic (Ndukong, 2020). These positive initiatives are begging for concerted efforts and resolve to structure and fund medicinal research and its champions” (Ndukong, 2020). According to him,

…for a substance to be medically endorsed, it must go through the rigours of at least three clinical trials: a trial to gauge its level of toxicity. The second trial is conducted to determine its level of efficacy and side effects. And the third trial is carried to test its applicability in given populations.

Therefore, scientists should avoid the dangers of empiricism, especially with lethal outcomes” (Ndukong, 2020). Nonetheless, the question here is how African herbal products would undergo such rigour in the trials. Unfortunately, however, global institutions are not ready to fund such initiatives and projects, especially when the masses question Africa's dependency and reliance on foreign aid.

Analyses On The Literature For Alternate Approaches In Africa and Contribution To Policy

Recent developments and backlash that Africa, especially South Africa, faces after discovering the Omicron variant (BBC News, 2021) has brought inequity in the distribution of vaccines to what is referred to as a global pandemic. Nonetheless, the case we are making here is that if African leaders had put more effort into sponsoring research projects on locally made medicinal products, we would not be here complaining that we are being neglected. For instance, when the COVID-19 outbreak was announced, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, the then African Union chairperson, quickly sought to raise funds for a collective continental effort (Medinilla et al., 2020, p. 272). As a result, the initiative witnessed high levels of pledges. Still, the argument here is that such an initiative would have been applauded if it had as objective to set up structures that would develop and foster locally made products to fight the pandemic. According to Catherine Kyobutungi, executive director of the African Population and Health research centre in Nairobi, Kenya:

“It is disingenuous to cry foul and demand the most stringent forms of accountability for one type of science and then bend the rules for another” (Nordling, 2020).

During the Ebola crisis, member states established various research centres to strengthen public health systems and improve surveillance, emergency response, and prevention of infectious diseases. Most significantly, in collaboration with all African Union Heads of State, West African heads of state recognised the need for a Specialised Agency to immediately mitigate the spread of Ebola. This led to the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) in January 2017 (MO Ibrahim Foundation, 2020). The argument here is that we do not lack scientists and experts if such a centre could be created. However, the question is, has African leaders enabled the centre financially and infrastructurally to conduct and carry out experiments based on local herbs.

Furthermore, does the centre operate autonomously without taking directives from elsewhere? Moreover, the novel pandemic Ebola prompted calls to accelerate efforts to establish an African Medicines Agency (AMA) like the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in developing economies. As a result, the African states jointly established African national regulators with regulatory guidance on new medicines as the EMA does in Europe to treat Ebola. According to Irwin (2021), the African Union and the Africa CDC's continuity would need an estimated $100 million for effective operation. However, the debate is that very little has been heard about promoting the continuity of such research centres that promote ethnomedicine and Western-centric medicine to treat and cater to any emergency.

Another argument presented in some literature is that western donors will not have the enthusiasm and political will to sponsor and fund projects that will make African states independent and, hence, not purchase the vaccine (Marriott and Maitland, 2021). However, since the outbreak of the novel pandemic, western governments have been very instrumental in funding their pharmaceutical companies to come up with vaccines (Marriott and Maitland, 2021). These vaccines are later imposed and sold to the global economy, including the African continent, at mandatory prices. Moreover, pharmaceutical companies have also decided to monopolise and refuse to fully transfer vaccine technology and the technical know-how on vaccine production, coupled with specialists to developing countries (Marriott and Maitland, 2021). As a result, the call for African scientists and the government to focus on funding home-based projects is paramount instead of relying on western donors.

There is also the issue of double standards for regularising African traditional medicine. When it comes to conventional medicine from Africa. The World Health Organisation and Africa Centers for Disease Control have often cautioned the public against using ethnomedicine as the efficacy has not yet been proven. The reasons are that the purported team of experts is investigating and still approving the products based on what clinical trials presents (Bright et al., 2021, p. 7). On the other hand, such approval ratings and practices hardly question Western medicine. For instance, sources have it that the Food and Drug Administration advisory panel “have narrowly endorsed the use of Merck and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics' oral Covid treatment pill. This endorsement was conducted despite questions about the drug's effectiveness, safety and whether it would help the virus mutate into even more dangerous variants” (Kimball, 2021). This is also the case with the Pfizer antiviral drug Paxlovid that was announced a day after the UK had approved Merck (Ledford, 2021) despite questions surrounding missing details of the clinical trials of the drug as well as issues of possible mutations once the drugs are administered (Ledford, 2021). Scholars argued the efficacy of authorising most vaccines if creating a drug is “more challenging” than developing vaccines, as Kin-Chow Chang, a professor at Nottingham University, rightly puts it (Kuchler et al., 2021). This states that whilst stringent accountability is required for African medicine, the roles are bent for others because they come from the west. The narrative-driven out there is that Africa is incapable and lacks the expertise.

Conclusion

The study debates how the entire scientific community, not only in Africa but also across the world, move toward embracing the use of traditional medicine as a potential therapeutic approach, not merely in treating Covid-19 infection, but also in treating many other infectious diseases and non-communicable diseases. In particular, how should western medicine be used in a collaborative manner alongside traditional medicine, or how should traditional medicine complement western medicine in the health system also warrants some discussion/reflection.

The paper conceptualises the criticism of Western-centric medicine and investigates the promotion of alternate approaches in the African economy. The article situates the study context by exploring the African economy's socio-politics and public health governance. The advent of COVID-19 as a new pandemic in the global economy has led the public to seek an alternative health cure. Since its inception, the politics and belief systems on its treatment made people, especially in the African continent, to seek alternatives ways for a supposed “cure.” The full impact of Covid-19 is yet to be fully understood, and while there are many unknowns, the rapid and continued reliance on the internet cannot be denied.

The emergence of conventional medicine, also referred to as “Ethnomedicine,” has been considered to alleviate and cure COVID-19 and its symptoms. Many researchers and practitioners on herbal medicine believe the low impact of COVID-19 on the African communities is because of the local herbal remedies. Even though there is no formal approval on “ethnomedicine or traditional medicine by the regulatory bodies, many promising results emerged on applying for conventional medicine in managing Covid-19 in the continent. Some Global Economy and World Health Organisations have discouraged the usage of traditional medicine for COVID-19 treatment. However, some African states such as Tanzania, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea Conakry and Togo have engaged with formal researchers to see if traditional medicine can treat Covid-19. Nevertheless, there is still a lot of hesitancy amongst African populations in getting vaccinated.

Nonetheless, one can argue that based on the results garned from literature that has been reviewed especially in countries such as Lesotho and Cmaeroon it is evident that making use of traditional medicine as a potential therapeutic approach to curing COVID-19 has been working wonders. The lesson here is that if traditional medicine has made such strides in this era of COVID-19 it is high time for governments and institutions that be to forged synergies to see how more research can be conducted not only to expand and to make available herbal medicine for Covid but also to assist in getting a cure for other infectious diseases and non-communicable diseases. Moreover, there is a need for more research to be conducted that will reveal ways through which modern and traditional medicine can be integrated.

Whilst the need for such research is vital, one way through which such intergration can be harnessed is by exchange of patients. This is a process whereby patients who have not fared well with the administration of one medicine can opt to try the other.

The paper concludes that Africa could consolidate the readily available knowledge and give opportunities to traditional medical therapies that are cheap, convenient and safe for public health, especially for COVID-19 supposedly cure.

Author's Note

To start with, it is important to note that the topic itself titled “Western Centric Medicine for Covid-19 and its Contradictions: Can African Alternate Solutions be the Cure”? is in itself a contribution in that it provides a complete shift from the western mindset to Pan African mindset that is set out to argue that Africa is capable of providing medical and health solutions to some of the global pandemics. The paper goes further to expose some of the double standards measures when it comes to the authorization of African medicinal herbs as opposed to western medicines. It is in this perspective that the authors argue that it is high time for African leaders to demonstrate leadership and speak with one voice through the provision of funds to help boost the capacities of African medical researchers in African herbs. The data and literature has proven that Africa's contribution in the field of medicine especially herbal medicine has for a long time been relegated of which there is potential for it to be developed for the global use.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The paper's publication is sponsored by the Institute of Pan African Thought and Conversation (IPATC), University of Johannesburg.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adesina, M. A. (2020). The health status and demographics of a conflicting country: the Sudan experience. Eur. J. Environ. Public Health 4:em0032. doi: 10.29333/ejeph/5933

Badu, K., Thorn, J. P., Goonoo, N., Dukhi, N., Fagbamigbe, A. F., Kulohoma, B. W., et al. (2020). Africa's response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the nature of the virus, impacts and implications for preparedness. AAS Open Res. 3:19. doi: 10.12688/aasopenres.13060.1

BBC News (2021). Covid: South Africa' punished' for Detecting New Omicron Variant. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-59442129 (accessed December 12, 2021).

Bright, B., Babalola, C. P., Sam-Agudu, N. A., Onyeaghala, A. A., Olatunji, A., Aduh, U., et al. (2021). COVID-19 preparedness: capacity to manufacture vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics in sub-Saharan Africa. Global. Health 17:24. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00668-6

BusinessTech. (2021). Second Phase of South Africa's Covid-19 Vaccinations to begin May 17 2021. BusinessTech SA News 9th April 2021. Available online at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/481939/second-phase-of-south-africas-covid-19-vaccinations-to-begin-on-17-may/ (accessed May 24, 2021).

Cameroon Tribune (2020). Fight Against the Coronavirus: Archbishop Keida Receives a Special Prize. Available online at: https://www.cameroon-tribune.cm/article.html/36662/en.html/fight-against-the-coronavirus-arch-bishop-kleda-receives-special (accessed November 26, 2020).

Dzimanarira, T., Nachipo, B., Phiri, B., and Mashuka, E. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccine roll-out in South Africa and Zimbabwe: urgent need to address community preparedness, fears and hesitancy. Vaccines. 9:250. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030250

Elujoba, A. A., Odeleye, O. M., and Ogunyemi, C. M. (2005). Traditional medicine development for medical and dental primary health care delivery system in Africa. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2, 46–61. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v2i1.31103

Emeh, I. E. J. (2013). Dependency theory and Africa's underdevelopment: a paradigm shift from pseudo-intellectualism: the Nigerian perspective. Int. J. Afr. Asian stud. 1, 16–128. Available online at: https://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JAAS/article/view/9107/9325

Financial Times (2021). Africa's Covid-19 Corruption: ‘Theft Doesn’t Even Stop During a Pandemic.’ Avaialble online at: https://www.ft.com/content/617187c2-ab0b-4cf9-bdca-0aa246548745 (accessed January 11, 2022).

Gao, S., Ying, M., Yang, F., Zhang, J., and Yu, C. (2020). Zhang Boli: Traditional Chinese Medicine Plays a Role in the Prevention and Treatment on Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. in Open Access Online-First Publ res pap COVID-19, Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. 121–124. Available online at: http://en.gzbd.cnki.net/GZBT/brief/Default.aspx.

Gebremeskel, A. T., Otu, A., Abimbola, S., and Yaya, S. (2021). Building resilient health systems in Africa beyond the COVID-19 pandemic response. BMJ Glob Health 6:e006108. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006108

Gilbert, M., Pullano, G., Pinotti, F., Valdano, E., Poletto, C., Boëlle, Y., et al. (2020). Preparedness and vulnerability of African countries against importations of COVID-19: a modelling study. Lancet 395, 871–877. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30411-6

Gostin, L. O., Moon, S., and Meier, B. M. (2020). Reimagining global health governance in the age of COVID-19. Am J Public Health. 110, 1605–1623. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305933

Government of Lesotho (2020). NUL Covid-19 Potential Treatment Kills Virus. Available online at: https://www.gov.ls/nul-covid-19-potential-treatment-kills-virus/ (accessed November 15, 2021).

Hensel, A., Bauer, R., Heinrich, M., Spiegler, V., Kayser, O., Hempel, G., et al. (2020). Challenges at the time of COVID-19: opportunities and innovations in antivirals from nature. Planta Med. 86, 659–664. doi: 10.1055/a-1177-4396

Hoije, K., and Lukong, P. (2021). Virus-Funds Scandal Prompts Calls for IMF to Halt Cameroon Loan. Availabe at: Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-06-18/virus-funds-scandal-prompts-calls-for-imf-to-halt-cameroon-loan (accessed January 11, 2022).

Irwin, A. (2021, April 21). How covid spurred africa to plot a vaccine revolution. Nature. Available online at: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01048-1 (accessed December 9, 2021).

Kim, Y. I., Kim, S. G., Kim, S. M., Kim, E. H., Park, S. J., Yu, K. M., et al. (2020). Infection and rapid transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in ferrets. Cell Host Micro. 27, 704–709. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.023

Kimball, S. (2021). FDA Advisory Panel Narrowly Endorses Merck's Oral Covid Treatment Pill, Despite Reduced Efficacy and Safety Questions. Available online at: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/11/30/fda-advisory-panel-narrowly-endorses-mercks-oral-covid-treatment-pill-despite-reduced-efficacy.html (accessed December 02, 2021).

Kindzeka, M. E. (2021). Cameroon Investigates Missing $335 Million in COVID Funds. Available online at: https://www.voanews.com/a/africa_cameroon-investigates-missing-335-million-covid-funds/6206445.html (accessed January 11, 2022).

Kuchler, H., Smyth, J., Neville, S., and Mancini, D. P. (2021). The Covid drugs are finally here. The Financial Times. Available online at: https://www.ft.com/content/30efb138-0223-4b84-a30f-79f0e018a4b8 (accessed December 02, 2021).

Ledford, H. (2021). COVID Antiviral Pills: What Scientists Still Want to Know. Avialalble online at: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03074-5 (accessed December 02, 2021).

Lone, S. A., and Ahmad, A. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic - an African perspective. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 1300–1308. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1775132

Lou, B., Li, T. D., Zheng, S. F., Su, Y. Y., Li, Z. Y., Liu, W., et al. (2020). Serology characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 infection after exposure and post-symptom onset. Eur. Respir. J. 56:2000763. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00763-2020

Marriott, A., and Maitland, A. (2021). The Great Vaccine Robbery Pharmaceutical Corporations Charge Excessive Prices for COVID-19 Vaccines While Rich Countries Block Faster and Cheaper Route to Global Vaccination. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/The%20Great%20Vaccine%20Robbery%20Policy%20Brief%20final.pdf (accessed December 01, 2021).

Medinilla, A., Byiers, B., and Apiko,. (2020). African Regional Responses to COVID-19. ECDPM Discussion Paper No. 272.

Menezes, N. P., Simuzingili, M., and Yilma, Z. (2021). What Is Driving COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Africa Can End Poverty. Available online at: https://blogsworldbankorg/africacan/what-driving-COVID-19-vaccine-hesitancy-sub-saharan-africa. (accessed October 11, 2021).

MO Ibrahim Foundation (2020). Covid-19 In Africa: A Call for Coordinated Governance, Improved Health Structures and Better Data. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2020%20COVID-19%20in%20Africa.pdf (accessed December 01, 2021).

Ndukong, K. H. (2020). COVID-19 Treatment: Endogenous Cures Can also do the Trick! Available online at: http://en.people.cn/n3/2020/0526/c90000-9694588.html (accessed May 26, 2021).

Nkengasong, J. N., and Mankoula, W. (2020). Looming threat of COVID-19 infection in Africa: act collectively, and fast. Lancet 395, 841–842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30464-5

Nordling, L. (2020). Unproven Herbal Remedy Against Covid-19 Could Fuel Drug-Resistant Malaria, Scientists Warn. Available online at: https://www.science.org/content/article/unproven-herbal-remedy-against-covid-19-could-fuel-drug-resistant-malaria-scientists#:~:text=HEALTH-,Unproven%20herbal%20remedy%20against%20COVID-19%20could%20fuel%20drug-resistant%20malaria%2C%20scientists%20warn-Several%20African%20leaders (accessed November 18, 2021).

Obi-Ani, N. A., Anikwenze, C., and Isiani, M. C. (2020). Social media and the Covid-19 pandemic: observations from Nigeria. Cogent Arts Humanit. 7:1799483. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2020.1799483

Oleribe, O. O., Momoh, J., Uzochukwu, B. S., Mbofana, F., Adebiyi, A., Barbera, T., et al. (2019). Identifying key challenges facing healthcare systems in Africa and potential solutions. Int. J. Gen. Med. 12, 395–403. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S223882

Reuters. (2020). Cameroon Archbishop Says Treating COVID-19 With Plant-Based Remedy. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-cameroon-treatment-idINKBN23N30Y (accessed June 16, 2021).

Roets, N. (2021). Debt- another side effect of the Coronavirus. Mail and Guardian (2021). Available online at: https://mg.co.za/special-reports/2021-02-15-debt-another-side-effect-of-the-coronavirus/ (accessed May 7, 2021).

SABC News (2021). National University of Lesotho Makes Strides Towards the Possible Treatment of COVID-19. #Coronavirus #COVID19News. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KQOIx5sORIc (accessed August 23, 2021).

Sambala, E. Z., Kanyenda, T., Iwu, C. J., Iwu, C. D., Jaca, A., and Wiysonge, C. S. (2018). Pandemic influenza preparedness in the WHO African region: are we ready yet? BMC Infect. Dis. 18:567. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3466-1

Singh, J. A. (2020). COVID-19: Science and global health governance under attack. South African Medical J. 110, 445–446. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2020v110i5.14820

Sunkel, O. (1969). National development policy and external dependence in Latin America. J. Dev. Stud. 6, 23–48. doi: 10.1080/00220386908421311

Tih, F. (2020). Cameroon PM Meets Archbishop Over COVID-19 Herbal Cure. Avaialble at: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/cameroon-pm-meets-archbishop-over-covid-19-herbal-cure/1854713 (accessed November 16, 2021).

Tsao, S. F., Chen, H., Tisseverasinghe, T., Yang, Y., Li, L., and Butt, Z. A. (2021). What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: a scoping review. Lancet Digital Health 3:e175–e194. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30315-0

United Nation Millennium Development Goals (2015). Available online at: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf (accessed November 15, 2021).

Uwazie, I. U., Igwemma, A. A., and Ukah, F. I. (2015). Contributions of Andre Gunder Frank to the Theory of Development and Underdevelopment: Implications on Nigeria's Development Situation. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 6, 27–38.

Van Ryneveld, M., Schneider, H., and Lehmann, U. (2020). Looking back to look forward: a review of human resources for health governance in South Africa from 1994 to 2018. Hum. Resour. Health 18: 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00536-1

WHO (2020). WHO Supports Scientifically-Proven Traditional Medicine |WHO| Regional Office for Africa. WHO Support Sci Tradit Med. Available online at: https://www.afro.who.int/news/who-supports-scientifically-proven-traditional-medicine?gclid=CjwKCAjwjLD4BRAiEiwAg5NBFlOWbdSg5OgzIsNBICCwbaCndOvz_Nk8onOJzRLqZw9YhMVHMhRsbxoC9_wQAvD_BwE

WHO (2021a). WHO Affirms Support for COVID-19 Traditional Medicine Research. Available online at: https://www.afro.who.int/news/who-affirms-support-covid-19-traditional-medicine-research (accessed November 15, 2021).

WHO (2021b). Status of COVID-19 Vaccines Within WHO EUL/PQ Evaluation Process. Available online at: https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/sites/default/files/documents/Status_COVID_VAX_11Nov2021.pdf (accessed November 15, 2021).

Keywords: Western-centric medicine, socio-politics, public health governance, ethnomedicine/traditional medicine, Africa

Citation: Adunimay AW and Ojo TA (2022) Western Centric Medicine for Covid-19 and Its Contradictions: Can African Alternate Solutions Be the Cure? Front. Polit. Sci. 4:835238. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.835238

Received: 14 December 2021; Accepted: 31 March 2022;

Published: 27 April 2022.

Edited by:

Olawale Oni, Osun State University, NigeriaReviewed by:

Si Ying Tan, National University of Singapore, SingaporeSenayon Olaoluwa, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Copyright © 2022 Adunimay and Ojo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anslem Wongibeh Adunimay, anslemo81@yahoo.fr; Tinuade A. Ojo, tinuadeojo@gmail.com; orcid.org/0000-0001-6086-7173

Anslem Wongibeh Adunimay

Anslem Wongibeh Adunimay Tinuade A. Ojo

Tinuade A. Ojo