Abstract

COVID-19 disproportionately affects older people, with higher rates of infection and a higher risk of adverse outcomes. A brief review of literature was undertaken to inform development of a protocol describing the indications and process of prone positioning to aid the management of COVID-19 infection in non-mechanically ventilated, awake older adults. PubMed was searched up to 14th January 2021 to identify English language papers that described prone positioning procedures used in non-mechanically ventilated patients. Data were pooled to inform the development of a prone positioning protocol for use in hospital ward environments. The protocol was trialled and refined during routine clinical practice. Screening of 146 articles yielded five studies detailing a prone positioning protocol. Prone positioning is a potentially feasible and tolerated treatment adjunct for hypoxaemia in older adults with COVID-19. Future studies should further establish the efficacy, safety, and tolerability in respiratory illnesses in non-intensive care settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Older adults are disproportionately affected by COVID-19 infection (1). Age is an independent predictor of mortality (2). The presence of co-morbidities (3) as well as age-related changes in physiology (4) contribute to this risk. Furthermore, older adults are less likely to present with the typically described symptoms of dyspnoea, anosmia, cough and fever but rather with atypical symptoms such as delirium (5) which may negatively impact time to diagnosis and subsequent treatment (6). The World Health Organisation issued guidance in March 2020 (updated May 2020) on the management of COVID-19 infection in older adults (7), which has been mirrored in UK guidance (8, 9). It recommended that all older adults are screened for COVID-19 when accessing healthcare and medications should be reviewed. It advocates establishing whether an advance care plan is in place and working within a multidisciplinary team. The mainstay of current management in hospital ward environments comprises oxygen, dexamethasone (7, 10), and potentially remdesivir if disease is severe (11). Respiratory decompensation occurs around day 10 of illness (12) whereby COVID-19 associated Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) manifests as profound hypoxaemia often in the absence of apparent dyspnoea (13, 14).

Prone positioning was first described as a therapeutic strategy to relieve hypoxia in the 1970s (15). Randomised controlled trials have established that it is associated with improved outcomes in those with ARDS and respiratory failure (16–18). Prone positioning is associated with increased end-expiratory lung volume, alveolar recruitment and oxygenation (19), reduction in pressure differential across anterior and posterior lung tissue and improvement in ventilation/perfusion mismatch, which is exacerbated by ARDS (20). It is commonly used during anaesthesia and during the immediate postoperative period in patients who are intubated and ventilated (21). Cost effectiveness has been established in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) setting in those with severe ARDS (22). During the COVID-19 pandemic, small studies, specifically in awake patients, suggest that prone ventilation is feasible in Emergency Department (ED) settings (23, 24), ICU (25–32), and in ward-based settings (33–37) with participants receiving standard oxygen therapy, high-flow nasal oxygen, or non-invasive ventilation in the form of continuous positive airway pressure.

Prone positioning has potential utility as an adjunct to a rather limited repertoire of treatment strategies available for older adults in hospital with COVID-19 infection. We sought to perform a brief review of the literature to develop a protocol for prone positioning that would assimilate existing evidence, particularly considering the specific needs and requirements of older adults. On this basis, we developed a prone positioning protocol designed to be used specifically in older adults with COVID-19 infection cared for in standard ward environments. We tailored this protocol specifically to the needs of older adults receiving supplemental oxygen via nasal cannuale, face mask air-entrainment mask or non-rebreathe mask in normal ward settings recognising that this will be relevant to a significant proportion of older people. Additional measures already described elsewhere (25–32) for proning in settings with facilities and expertise that permit more invasive respiratory support.

Methods

A search of PubMed was carried out up to 14th January 2021 using the following search criteria: (prone position[MeSH terms]) OR (Prone [MeSH Terms]) AND (Aged [MeSH Terms]) OR (Frail Older adult [MeSH terms]) OR (Elderly [MeSH terms]). Abstracts were searched to determine papers that described the process of proning, efficacy and/or considerations in non-intubated older adults outside of ICU settings and potential complications. Combinations using COVID-19 or coronavirus, sars [MeSH terms] did not retrieve any additional relevant results. Further articles were identified through reference and citation lists. Results were collated to inform the development of a proning protocol suitable for use in older adults.

Results

Of the 146 articles on the use of prone positioning in patients with respiratory conditions that were identified, 32 were relevant to non-mechanically ventilated patients but only five provided details of a proning procedure. Of the remaining 27 studies, two focused on nerve injury relating to prone positioning; a case study (38) and a case series (39). The case series found that 15% of 83 patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation facilities post-COVID-19 were diagnosed with peripheral nerve injury, 92% of whom had been proned in acute care. Five studies examined patients with ARDS (22, 40–43).

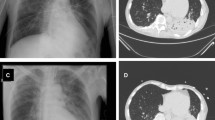

The remaining 25 studies included patients with COVID-19 infection supported with non-invasive ventilation. One study sought to describe sputum characteristics of patients with severe COVID-19, and to determine the effect of airway clearance methods on outcomes in these patients (47) whilst another examined the expansion of the lungs in supine versus prone in COVID-19 using CT scan (48).

The optimal duration of proning has not been determined. Three studies reported a duration of 3 hours or fewer (24, 28, 32), 5 studies reported a duration over 3 hours per day (26, 29, 30, 36, 50), and 3 reported a range across patients: <1hour, 1–3 hours and >3 hours (34), 1–16 hours (25), up to 24 hours a day (35) and 5 studies did not report the duration of proning (27, 31, 33, 37, 49). The results of the studies which did report duration of proning did not provide conclusive evidence to suggest a consensus on optimal duration in the COVID-19 population, although studies that compared duration show a trend towards longer duration being of greater benefit (34, 35).

Five of the 32 studies provided significant detail on the methods of a proning procedure (24, 36, 44–46) and were used to develop our protocol. Two tested the protocol in patients with non-invasive ventilation (24, 36), and 3 described a protocol but did not test it in patients (44–46). Using the data from these 5 articles and from relevant clinical guidelines (51–54), coupled with clinical experience, a protocol was designed by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in caring for older adults with acute COVID-19 infection.

Protocol

This protocol, shown in Figure 1, covers the indications, proning manoeuvre and requisite monitoring. The proning manoeuvre to assist an individual from supine to prone is shown in Figure 2.

Step 1 — Patient selection and suitability

Prone positioning can be trialled for patients who require supplemental oxygen to maintain saturations ≥92% (or ≥88% in the presence of hypercapnic respiratory failure), without severe delirium or impairment in cognition that would preclude compliance with the procedure. Contraindications include spinal instability, unstable pelvic or facial fracture, anterior open wounds or burns, and raised intracranial pressure. In the presence of any relative contraindications, including head injury, uncontrolled seizures, raised intraocular pressure, cardiovascular instability, delirium and morbid obesity, clinical judgement should be used to balance the potential risks and benefits which should be discussed with the patient wherever possible. The relative risks and benefits should be explained, and consent gained where feasible.

Step 2 — Assemble equipment

Up to five staff members may be necessary depending on the degree of assistance required, and appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) should be worn. The patient’s ability to rotate their cervical spine and head to 45–90° should be checked. All clothing and jewellery should be removed to minimise the risk of a subsequent pressure injury. In advance of the manoeuvre, adequate tubing length and positioning should be checked anticipating the eventual prone position. Suction should be available and functioning. Pre-oxygenation with high flow oxygen via a non-rebreathe mask may be considered where exertion leads to critical desaturation. Given the higher risk to this population of developing pressure injuries, it is strongly recommended that patients should be on an air mattress. Bladder catheter tubing and bags should be placed on the bed, between the legs, rather than affixed to the bedside.

Step 3 — Recording of observations

Older adults are more prone to pressure injury and therefore specific care should be taken of the face, malar area, ears, eyes, shoulders, elbows, breasts, iliac crests, knees and toes (55). Particular attention should be paid to the bridge of the nose for those wearing a face mask, the columella for those wearing nasal cannulae, and the tops of the ears in both instances. Prior to the proning manoeuvre, it is recommended that anterior electrocardiographic electrodes are removed if in situ. These can be reapplied to the posterior chest post-manoeuvre if electrocardiographic monitoring is required. Skin integrity and heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturations, temperature, respiratory rate and conscious level should be monitored (51, 54).

Step 4 — Proning manoeuvre

Patients should be encouraged to position themselves independently where they are able. If assistance is required, one individual should co-ordinate the manoeuvre which is achieved by means of a slidesheet-assisted manual handling technique (Figure 2). Once positioning, secretions should be suctioned, and bed angled to 10° (reverse Trendelenburg) which increases adherence, and reduces aspiration risk (52).

Step 5 — Monitoring

Once in the prone position, observations should be recorded at 15 minute intervals for the first hour and according to clinical judgement thereafter. The optimal duration of proning is uncertain with studies of proning in COVID-19 infection reporting a duration of 1–21 hours per day (34, 36). Establishing treatment goals early on will allow the team to assess whether the patient is responding to the proning protocol. There is no strong evidence base to guide the duration after which an individual can be deemed to have responded. Therefore response should be assessed according to clinical judgement with regular proning cycles implemented thereafter in those with satisfactory response. Our experience has been to prone patients as tolerated with shorter recurrent periods prone often facilitating adequate nutrition and hydration at mealtimes. Hourly repositioning, alternating flexion and extension of the arms, with head turned “face facing hand” should be undertaken. If the patient is unable to comply with the positioning requirements we do not advocate the use of physical restraints. Eyes should be lubricated, and face skin should be protected with hyper-oxygenated fatty acids and silicone dressings. Pillows can offload bony prominences such as shoulders, knees, toes and iliac crests and support the chest (52). Ensure oxygen delivery systems are correctly fitted and not too tight across pressure areas.

Step 6 — Post-manoeuvre

After repositioning, observations should be recorded, monitoring particularly for hypotension which can occur during sudden positional changes (56, 57).

Risks and special considerations

If the patient is receiving nutrition via nasogastric (NG) tube, this should be discontinued or aspirated at least one hour prior to the manoeuvre and prone, feed can be restarted at 10ml/h.

Recognised complications of proning include brachial plexus injury (38, 39), pressure ulcers (58, 59) and hypotension on returning to supine (57). As such, regular assessment of pain using a recognised pain score is useful. Proning precludes anterior chest wall observation and there is a risk that recognition of deterioration can be delayed. Whilst successful resuscitation is described in the prone position (60) we advocate that the patient is immediately returned to supine should this need arise. Staffing levels may be a significant factor in limiting feasibility in ward environments, and as such proning should be scheduled to allow for sufficient monitoring.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prone positioning protocol that has been specifically designed for older adults with COVID-19 who are cared for on geriatric or general medical wards. Our approach has been to combine a rapid review of the literature with our pragmatic experience of utilising proning as an adjunctive nonpharmacological therapy for treating older inpatients with COVID-19. The articles identified in the literature search provided information on patient inclusion and exclusion criteria (45, 46), patient positioning (24, 46), duration of proning (36), and physiological monitoring (44, 46) but these were not specific to older adults nor hospital ward settings. Relevant data were assimilated and integrated with specific knowledge of the care of older people to develop a protocol that specifically considered the high likelihood of concurrent delirium, cognitive impairment, limitations in mobility, comorbid conditions (such as fractures), pressure injury risk and tolerability.

When compared with other protocols, our protocol provides a comprehensive checklist, five detailed images which display the patient, equipment and the manoeuvre itself, and a clear description of indications and requisite monitoring pre-, peri- and post-maneuvre. Mitchell & Secka (2018) provide a thorough checklist (44), and Bastoni et al., (2020) provide two images and video footage of the procedure being undertaken (24). None of the five studies however combine all aspects. In addition, whilst Raoof et al., (2020) highlighted considerations such as pressure points (45), our protocol includes specific considerations in older adults, highlighting the complications which may arise including pressure injury.

We recognise the limitations of our approach has been to adapt protocols utilised in ICU settings (44), ED (46) or in ward-based settings (24, 36) not specific to older people. We anticipate that the protocol may be utilised as an adjunctive treatment for other respiratory conditions and that the optimal timing of initiation, duration of proning and effectiveness will be further established with future research.

Conclusions

Our experience suggests that with careful patient selection, proning is a feasible, well-tolerated procedure for those who are alert, willing and able to comply. Its use is not precluded by the presence of delirium or cognitive impairment so long as clinical judgement is exercised. We anticipate that this protocol may improve the safety and efficacy of prone positioning in older people.

References

Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: Prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369(March):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1985.

Mehraeen E, Karimi A, Barzegary A, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with COVID-19-a systematic review. Eur J Integr Med. 2020;40:101226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2020.101226.

Davis JW, Chung R, Juarez DT. Prevalence of comorbid conditions with aging among patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(10):209–213.

Boss GR, Seegmiller JE. Age-related physiological changes and their clinical significance. West J Med. 1981;135(6):434–440.

Gan JM, Kho J, Akhunbay-Fudge M, et al. Atypical presentation of COVID-19 in hospitalised older adults. Ir J Med Sci. Published online 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-020-02372-7.

Davis P, Gibson R, Wright E, et al. Atypical presentations in the hospitalised older adult testing positive for SARS-CoV-2: a retrospective observational study in Glasgow, Scotland. Scott Med J. Published online 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0036933020962891.

World Health Organisation. Clinical Management of COVID-19 — WHO Interim Guidance.; 2020.

National Institute For Health and Care Excellence (NICE). COVID-19 rapid guideline: critical care in adults. Natl Inst Heal Care Excell. 2020;(March):2020.

BMJ. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) — BMJ Best Practice. Vol 2019.; 2020.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. COVID-19 Prescribing Briefing: Corticosteroids COVID-19 Prescribing Briefing: Corticosteroids.; 2020.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. COVID-19 Rapid Evidence Summary: Remdesivir for Treating Hospitalised Patients with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 Key Messages.; 2020.

Ye Q, Wang B, Mao J. The pathogenesis and treatment of the ‘Cytokine Storm’ in COVID-19.’ J Infect. 2020;80(6):607–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037.

Ragab D, Salah Eldin H, Taeimah M, Khattab R, Salem R. The COVID-19 Cytokine Storm; What We Know So Far. Front Immunol. 2020;11(June):1–4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01446.

Tobin MJ, Laghi F, Jubran A. Why COVID-19 silent hypoxemia is baffling to physicians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(3):356–360. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202006-2157CP.

Piehl MA, Brown RS. Use of extreme position changes in acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 1976;4(1):13–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-197601000-00003.

Taccone P, Pesenti A, Latini R, et al. Prone positioning in patients with moderate and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA — J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302(18):1977–1984. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1614.

Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard J-C, et al. Prone Positioning in Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2159–2168. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1214103.

Mancebo J, Fernández R, Blanch L, et al. A multicenter trial of prolonged prone ventilation in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2006;173(11):1233–1239. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200503-353OC.

Dirkes S, Dickinson S, Havey R, O’Brien D. Prone positioning: Is it safe and effective? Crit Care Nurs Q. 2012;35(1):64–75. https://doi.org/10.1097/CNQ.0b013e31823b20c6.

Koulouras V, Papathanakos G, Papathanasiou A, Nakos G. Efficacy of prone position in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients: A pathophysiology-based review. World J Crit Care Med. 2016;5(2):121. https://doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v5.i2.121.

Furukawa H, Sato H, Hashizume K, et al. [Clinical Efficacy of Prone Positioning in Elderly Patients with Respiratory Failure after Thoracic Aortic Surgery]. Kyobu Geka. 2018;71(8):583–586.

Baston CM, Coe NB, Guerin C, Mancebo J, Halpern S. The Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions to Increase Utilization of Prone Positioning for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(3):e198–e205. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003617.

Caputo ND, Strayer RJ, Levitan R. Early Self-Proning in Awake, Non-intubated Patients in the Emergency Department: A Single ED’s Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(5):375–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13994.

Bastoni D, Poggiali E, Vercelli A, et al. Prone positioning in patients treated with non-invasive ventilation for COVID-19 pneumonia in an Italian emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(9):565–566. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2020-209744

Despres C, Brunin Y, Berthier F, Pili-Floury S, Besch G. Prone positioning combined with high-flow nasal or conventional oxygen therapy in severe Covid-19 patients. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):256. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03001-6.

González-Castro A, Escudero-Acha P, Arnaiz F, Ferrer D. High-flow oxygen therapy with spontaneous breathing prono position in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2020;67(9):529–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redar.2020.05.014.

Hallifax RJ, Porter BM, Elder PJ, et al. Successful awake proning is associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19: single-centre high-dependency unit experience. BMJ open Respir Res. 2020;7(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000678.

Taboada M, González M, Álvarez A, et al. Effectiveness of Prone Positioning in Nonintubated Intensive Care Unit Patients With Moderate to Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome by Coronavirus Disease 2019. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(1):25–30. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005239.

Slessarev M, Cheng J, Ondrejicka M, Arntfield R. Patient self-proning with high-flow nasal cannula improves oxygenation in COVID-19 pneumonia. Can J Anesth. 2020;67(9):1288–1290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01661-0.

Ferrando C, Mellado-Artigas R, Gea A, et al. Awake prone positioning does not reduce the risk of intubation in COVID-19 treated with high-flow nasal oxygen therapy: A multicenter, adjusted cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03314-6.

Damarla M, Zaeh S, Niedermeyer S, et al. Prone positioning of nonintubated patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(4):604–606. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202004-1331LE.

Retucci M, Aliberti S, Ceruti C, et al. Prone and Lateral Positioning in Spontaneously Breathing Patients With COVID-19 Pneumonia Undergoing Noninvasive Helmet CPAP Treatment. Chest. 2020;158(6):2431–2435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.006

Taboada M, Rodríguez N, Riveiro V, Baluja A, Atanassoff PG. Prone positioning in awake non-ICU patients with ARDS caused by COVID-19. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020;39(5):581–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2020.08.002.

Elharrar X, Trigui Y, Dols A-M, et al. Use of Prone Positioning in Nonintubated Patients With COVID-19 and Hypoxemic Acute Respiratory Failure. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2336–2338. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.8255.

Thompson AE, Ranard BL, Wei Y, Jelic S. Prone Positioning in Awake, Nonintubated Patients With COVID-19 Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1537. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3030

Ng Z, Tay WC, Benjamin Ho CH. Awake prone positioning for non-intubated oxygen dependent COVID-19 pneumonia patients. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(1):0–5. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01198-2020.

Ripoll-Gallardo A, Grillenzoni L, Bollon J, Della Corte F, Barone-Adesi F. Prone Positioning in Non-Intubated Patients with COVID-19 Outside of the Intensive Care Unit: More Evidence Needed. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;14(4):E22–E24. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.267.

Jiang LG, LeBaron J, Bodnar D, et al. Conscious Proning: An Introduction of a Proning Protocol for Nonintubated, Awake, Hypoxic Emergency Department COVID-19 Patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(7):566–569. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14035

Mitchell DA, Seckel MA. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Prone Positioning. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2018;29(4):415–425. https://doi.org/10.4037/aacnacc2018161.

Raoof S, Nava S, Carpati C, Hill NS. High-Flow, Noninvasive Ventilation and Awake (Nonintubation) Proning in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 With Respiratory Failure. Chest. 2020;158(5):1992–2002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.013.

Bamford AP, Bentley A, Dean J. ICS Guidance for Prone Positioning of the Conscious COVID Patient 2020. Intensive Care Soc. Published online 2020. https://emcrit.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2020-04-12-Guidance-for-conscious-proning.pdf.

Madathil S. Proning in the Ward-Based Awake Self-Ventilating Patient with COVID-19.; 2020.

Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for awake prone ventilation in the non-intubated conscious patient.; 2020. https://africacdc.org/download/guidance-for-awake-prone-ventilation-in-the-non-intubated-conscious-patient/

Tomalin L, Metcalfe A. NDDH Guidance for Prone Positioning Self — Ventilating Patients ± CPAP For COVID-19 2020.; 2020.

Hahnel E, Lichterfeld A, Blume-Peytavi U, Kottner J. The epidemiology of skin conditions in the aged: A systematic review. J Tissue Viability. 2017;26(1):20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtv.2016.04.001.

Tabara Y, Tachibana-Iimori R, Yamamoto M, et al. Hypotension associated with prone body position: A possible overlooked postural hypotension. Hypertens Res. 2005;28(9):741–746. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.28.741.

Manohar N, Ramesh VJ, Radhakrishnan M, Chakraborti D. Haemodynamic changes during prone positioning in anaesthetised chronic cervical myelopathy patients. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63(3):212. https://doi.org/10.4103/ija.IJA_810_18.

Malik GR, Wolfe AR, Soriano R, et al. Injury-prone: peripheral nerve injuries associated with prone positioning for COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(6):e478–e480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.08.045.

Sánchez-Soblechero A, García CA, Sáez Ansotegui A, et al. Upper trunk brachial plexopathy as a consequence of prone positioning due to SARS-CoV-2 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Muscle and Nerve. 2020;62(5):E76–E78. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.27055.

Moore Z, Patton D, Avsar P, et al. Prevention of pressure ulcers among individuals cared for in the prone position: lessons for the COVID-19 emergency. J Wound Care. 2020;29(6):312–320. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2020.29.6.312.

Ibarra G, Rivera A, Fernandez-Ibarburu B, Lorca-García C, Garcia-Ruano A. Prone position pressure sores in the COVID-19 pandemic: The Madrid experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2020.12.057.

Douma MJ, MacKenzie E, Loch T, et al. Prone cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A scoping and expanded grey literature review for the COVID-19 pandemic. Resuscitation. 2020;155(July 2020):103–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.07.010.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the constructive and helpful comments provided by the Reviewers.

Funding

DB, EJH and FEL receive salary support from The Gatsby Foundation. EJH has received grants from Parkinson’s UK, NIHR and The Gatsby Foundation, and has received travel consultancy and honoraria from Profile, Bial, Abbvie, Luye, Ever and Simbec Orion. The funders played no role in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of the data, or writing of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

How to cite this article: D.E. Brazier, N. Perneta, F.E. Lithander, et al. Prone Positioning of Older Adults with COVID-19: A Brief Review and Proposed Protocol. J Frailty Aging 2022;11(1)115-120; https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2021.30

Conflicts of Interest

DEB & FEL report grants from The Gatsby Foundation during the conduct of the study; NP has nothing to disclose; EJH reports grants from The Gatsby Foundation, The Dunhill Trust, and National Institute of Health Research, personal fees from Bial, Abbvie, Ever, Profile pharma, and Luye, outside the submitted work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brazier, D.E., Perneta, N., Lithander, F.E. et al. Prone Positioning of Older Adults with COVID-19: A Brief Review and Proposed Protocol. J Frailty Aging 11, 115–120 (2022). https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2021.30

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2021.30