Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated and accentuated an ongoing crisis of care. A historic lack of investment in care, especially in areas of elder care, has resulted in long-term care (LTC) facilities being the epicentre of the pandemic in various nations. In France, one-third of all coronavirus deaths have been in care homes, and in Canada almost 80 percent.[1] This is an international issue of concern, since in more than half of nations belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), population ageing has exceeded growth in the number of LTC workers. In many higher-income nations, deaths linked to the COVID-19 global pandemic have been concentrated in residential care facilities, including LTC facilities that house the elderly or those needing assisted living. Suddenly, the conditions of those working and living in these facilities have become a key concern for the public. LTC workers are predominantly women, and in Canada migrant and racialized minorities are overrepresented in the sector. In Canada, workers in this sector are low-paid, short-staffed and mostly part-time, who often piece together two or more jobs across many facilities.

COVID-19, as with other epidemics, exposes how such working conditions undermine infection control protocols and make workers and residents vulnerable to infection. This paper provides some context regarding the care crisis in LTC facilities, in particular its relationship with the type and skill mix of labour, including the degree to which immigrant workers are represented in this sector. It will highlight two of the contributing factors to this crisis; the first is the gendered and racialized devaluing of migrant labour so essential to this sector; the second is the role of the private sector and the unsustainable extraction of profits from this service and the labour that provides it.

Context

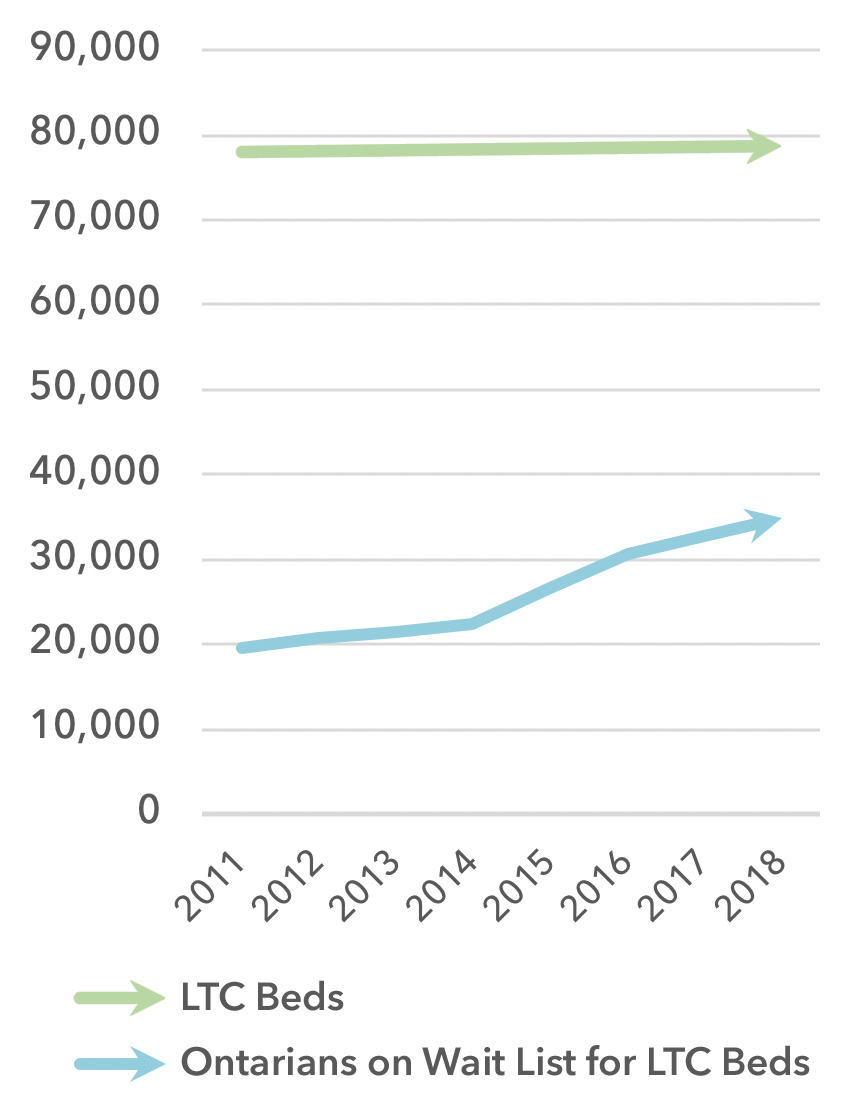

High-income nations face ageing populations in need of care, yet they often lack the necessary workforce to fulfill their needs. In France, for example, the number of individuals over 65 is set to increase by 40 percent by the year 2030.2 In Canada, those over 65 make up 15.6 percent of the population, and this demographic is set to grow to 23 percent by 2030.3 In OECD nations, 90 percent of LTC workers are women, and approximately 45 percent of them work part-time.4 In Canada, there is an average of four LTC workers per 100 individuals over 65. Ontario faces especially dire working conditions in LTC facilities, with studies indicating insufficient training for caregivers, rigid hierarchies within facilities, understaffed homes and poor levels of care.5 In Ontario, the provincial government has failed to fund LTC appropriately. Between 2011 and 2018, there was a 0.8 percent increase in available beds in public facilities, while the waitlist for beds almost doubled in number (see Figure 1).6 Pat Armstrong and colleagues contend that years of governments deprioritizing the sector have rendered those in care much more vulnerable to COVID-19.7

Figure 1: Number of LTC Beds in Ontario versus Number of Ontarians on the Wait List

(Source: Based on data from “Long-Term Care Homes Program: A Review of the Plan to Create 15,000 New Long-Term Care Beds in Ontario,” Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, 2019)

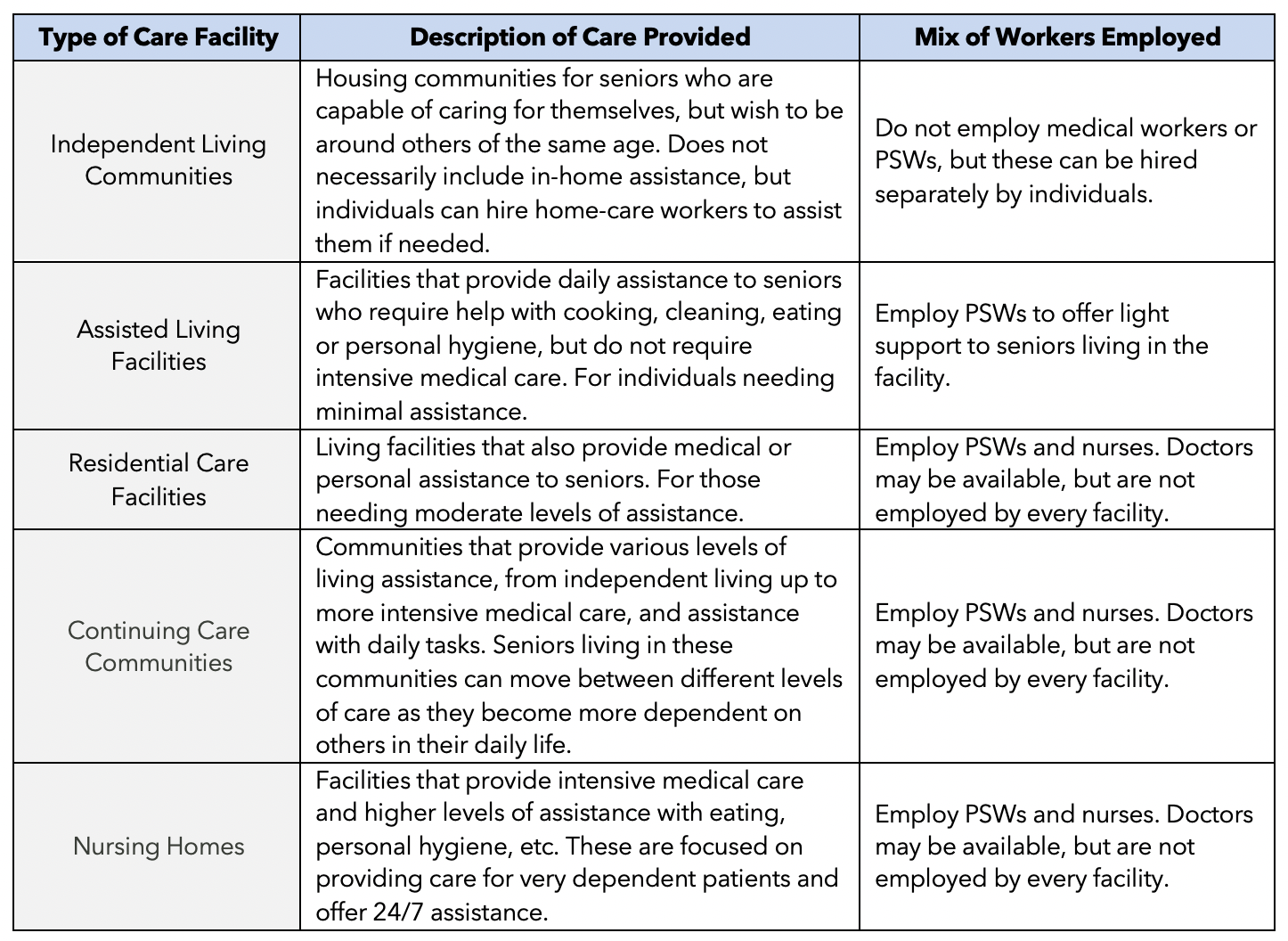

In Canada, residential care for those in need of assistance with daily living includes a range of facilities, many of which are assessed and monitored using the Continuing Care Reporting System (CCRS).8 The clinical data standard for CCRS uses a reporting system developed by interRAI, an international research network.9 There is a range of residential facilities, varying from short-term, post-acute care in skilled nursing facilities to long-term, chronic care and nursing home institutional settings. The degree of clinical care provided, and the skill mix of workers, differs across these institutions and can include physicians, nursing staff (registered nurses and registered practical nurses), other allied health professionals and personal support workers (PSWs). PSWs are unregulated care providers with no defined scope of practice, whose role has evolved to include functions formerly provided by regulated health professionals. As the intensity of care needs increases, the mix of workers includes more regulated professionals, but it is clear that PSWs are essential to most residential care facilities. Research has indicated that these these factors, combined with the variation in PSW education and employment standards, has significant implications for patient safety and quality of care.10 PSWs in this sector are low-paid, short-staffed, mostly part-time and often piece together two or more jobs across many facilities.11

Types of Residential Care Facilities and Workers Employed

Table 1: Types of Care Facilities, Description of Care and Workers Employed

(Source: Based on information from the National Caregivers Library and Barken & Armstrong, 2018)

LTC, PSWs and Migrant Labour

High-income nations have seen women move into the workforce without states providing social welfare systems to care for children and the elderly (that is, the unpaid labour that women traditionally provided).12 In these higher-income nations, care work has effectively been outsourced: from being the responsibility of women within the household, it is now racialized women from developing nations who leave their own families to care for others. This care labour is both commoditized and devalued, with compensation far below the actual value of the care provided. This process has been captured through the concept of “global care chains,” a series of global connections, or a chain, based on the paid and unpaid work of caring.13 These chains allow for the extraction of care, based on the exploitation of multiple divisions, including gender, ethnicity, class and uneven development. The World Health Organization (WHO) has referred to migrant women care workers as “a cushion for states that lack adequate public provision for long-term care, childcare and care for the sick.”14 The WHO identifies a “care paradox,” wherein migrant women work to fulfill the growing need for care workers in high-income and middle-income nations and strengthen weak health systems, while lacking health services themselves.15 This paradox is highlighted in the challenging role visible minority and migrant women play as care providers and PSWs in LTC homes, typically working in low-paid positions deemed “low-skilled,” while actually performing complex and essential services for vulnerable populations.16

Internationally, the number of migrant care workers in LTC is increasing. In the United States, as of 2011, one-in-four care workers in LTC were migrants, a five percent increase from 2005.17 In the United Kingdom, the number of migrant care workers more than doubled between 2001 and 2009, from seven percent to 18 percent.18 A similar trend can be found in Canada, with research suggesting migrant workers represent up to 50 percent of LTC caregivers in certain provinces.19 The demographic shift in who performs care labour in high-income nations is evident, and racial as well as gendered intersectional prejudice cannot be disassociated from the crisis of care in LTC homes and facilities. According to the 2016 census, visible minority workers are overrepresented as nursing home employees across all Canadian provinces.20

What is consistent across the literature is that care work is socially regarded as work to which women are naturally predisposed; it is thus essentialized as feminine labour and considered unskilled, which facilitates its devaluation.21 Immigration and employment policies, combined with these structural forms of gendered and racial discrimination, create precarious employment conditions for immigrant workers in this sector.22 Employers can naturalize this labour market segmentation by reproducing ideas about certain racial and cultural backgrounds making migrant workers better at caring for older populations, and less likely to complain about strenuous or difficult work conditions.23 Employers often believe that migrant workers are more likely to be willing to work longer hours, and are more flexible with shifts.24 Restrictive immigration status combines with these labour market contexts and makes it easier to retain immigrants in jobs with working conditions non-migrants would not tolerate. Additionally, immigrants might be attractive as “high-quality workers for low-skilled jobs,” especially in non-regulated occupations where skills can be determined by the employer and reflect their interests, including what they want to pay and how they want people to behave. Employers surveyed between 2007 and 2008 were more likely to employ migrants in non-professional positions than in professional ones such as doctors or registered nurses.25 These preconceptions can lead to problematic relationships between employers and workers, with employers opting to fire migrant workers before they complete the number of years necessary to become permanent residents and thereby access greater rights.26 Employers can leverage the precarious status of immigrant caregivers in order to pay lower wages and maintain working conditions more favourable to the employers’ interests.

A new approach to managing the burden of LTC is the offshoring of care. There are specific examples of the offshoring of dementia care to Thailand, for example, where Alzheimer’s patients from Switzerland and Germany move to Thailand to find quality LTC.27 The benefits of this offshoring are that the price of care in Thailand is significantly cheaper than in Europe and can be privately purchased, making it more accessible. At Baan Kamlangchay, an LTC facility for patients with dementia and Alzheimer’s, promotional literature states that each patient has three caregivers.28 The level of care a patient can get at this Thai facility is significantly better than a patient might receive in high-income nations that face shortages in caregivers and spaces in LTC. However, this offshoring of care is also rooted in problematic assumptions, mainly that Thai individuals care better for elders due to their cultural beliefs. Further, similar to the use of migrant labour locally, the use of women’s labour in places such as Thailand depends upon the ability to pay less for higher-quality care. The exploitation of women of colour occurs in a different context, but is based on the same assumptions about care being naturalized as feminine.

Financialization of LTC

Part of the larger debate about the crisis of elder care in high-income nations is how LTC should be financed. What is consistent across different nations is the sheer cost of LTC. In the next 30 to 40 years, high-income states will need to double spending in the LTC sector to keep up with ageing populations. For example, the European Commission estimates that the European Union will need to increase spending on LTC from 1.8 percent of GDP to 3.6 percent by 2060.29

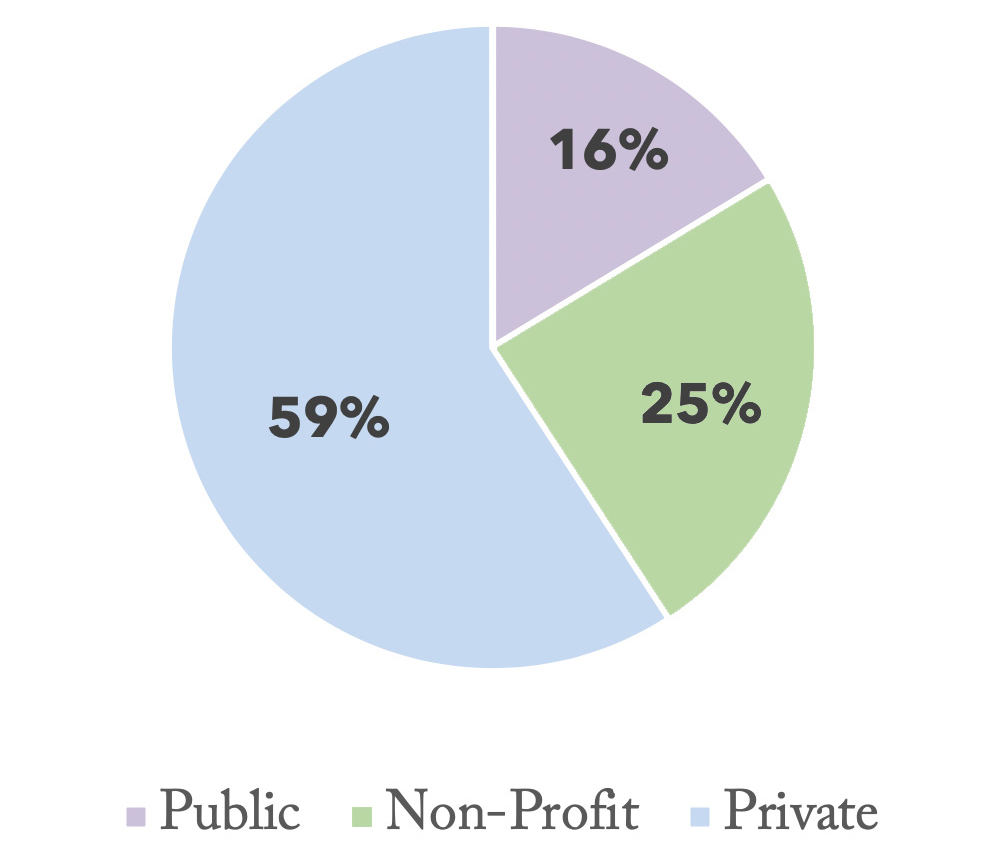

There are different political interests and approaches to the financing of LTC. In Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom, there has been growth in private ownership and operation of LTC facilities. In Alberta, for example, there has been a recent push toward selling two publicly owned LTC homes in order to cut costs, increase revenues and open up more beds.30 According to the Ontario Long-Term Care Association (OLTCA), 58 percent of LTC facilities are privately owned (see Figure 2).31 Furthermore, these facilities, both private and public, are facing shortages of nurses and PSWs, and this shortage has been especially deadly during the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

Figure 2: Breakdown of LTC Facility Ownership in Ontario

(Source: Based on OLTCA data)

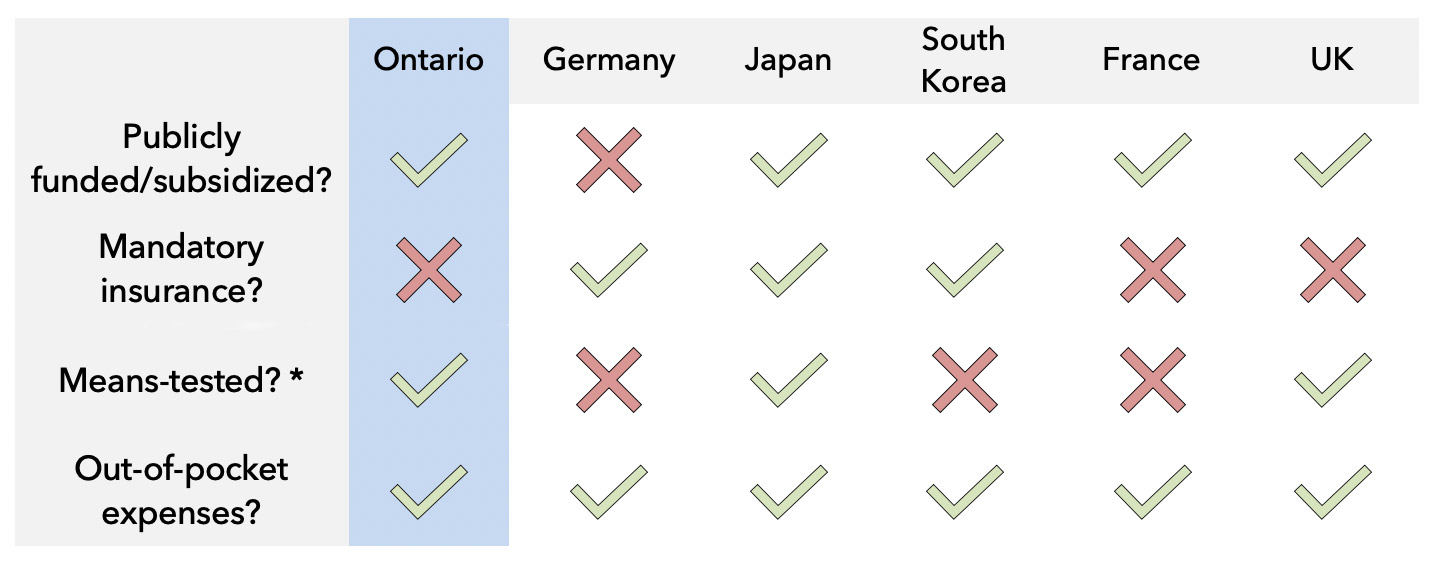

Despite the various approaches to funding LTC across the globe, approaches are generally unsustainable as the world population continues to age. In Germany, Japan and South Korea, citizens must “opt in” to mandatory insurance schemes to help finance their stay in LTC.32 In Japan, LTC is funded by the national government, with insurance premiums paid by citizens, and access to LTC is means-tested, with access dependent on age and ability.33 In Korea, the program is partially publicly funded, but not means-tested and universally covers citizens over 65.34 In France, LTC is publicly funded through taxation and has achieved around 70 percent coverage.35 In the United Kingdom, LTC is also publicly funded; however, patients face means-testing and some are also required to contribute to co-payments for living in the facilities.36 (See Table 2.)

Table 2: Global Approaches to Funding LTC

*i.e., is access based on need or only the desire to go into a long term-care facility?

(Sources: based on information from Glinskaya and Feng, 2018; Chevreul and Brigham, 2013 OECD and European Union, 2013)

In the United Kingdom, many LTC facilities are privately owned and managed. Small private companies often rely on banks to finance the LTC homes they own, and this type of funding is often stricter and more difficult to obtain. However, larger private organizations that own multiple LTC facilities have recently shifted to private equity firm investment, which, in comparison to public markets or banks, is more tolerant of high levels of debt.37 As a result, private equity firms such as Blackstone or Alliance are investing money in poorly managed and debt-encumbered LTC homes that would be deemed risky investments. The need for increased private investment comes as a result of increased austerity measures by the government and decreased public ownership and funding of LTC facilities in the United Kingdom. The private companies that own LTC facilities then choose to open branches that seek to serve poor and underserved communities in order to ensure that they receive the public funding available.38 These private equity firms make a profit through the buying, selling and investing in real estate assets, not through the daily business of managing the facilities and the care of patients. In the United Kingdom, LTC is regulated by the state through a quality assurance framework. Facilities are required to register with the Care Quality Commission and fulfill the requirements outlined by the commission.39 In this way, both public and private facilities are set to follow the same expectations. However, the opposing interests of private financial interests and government requirements make the operation of LTC complex, and effective regulatory oversight and enforcement necessary. Research suggests that non-profit providers offer higher-quality care than for-profit providers.40

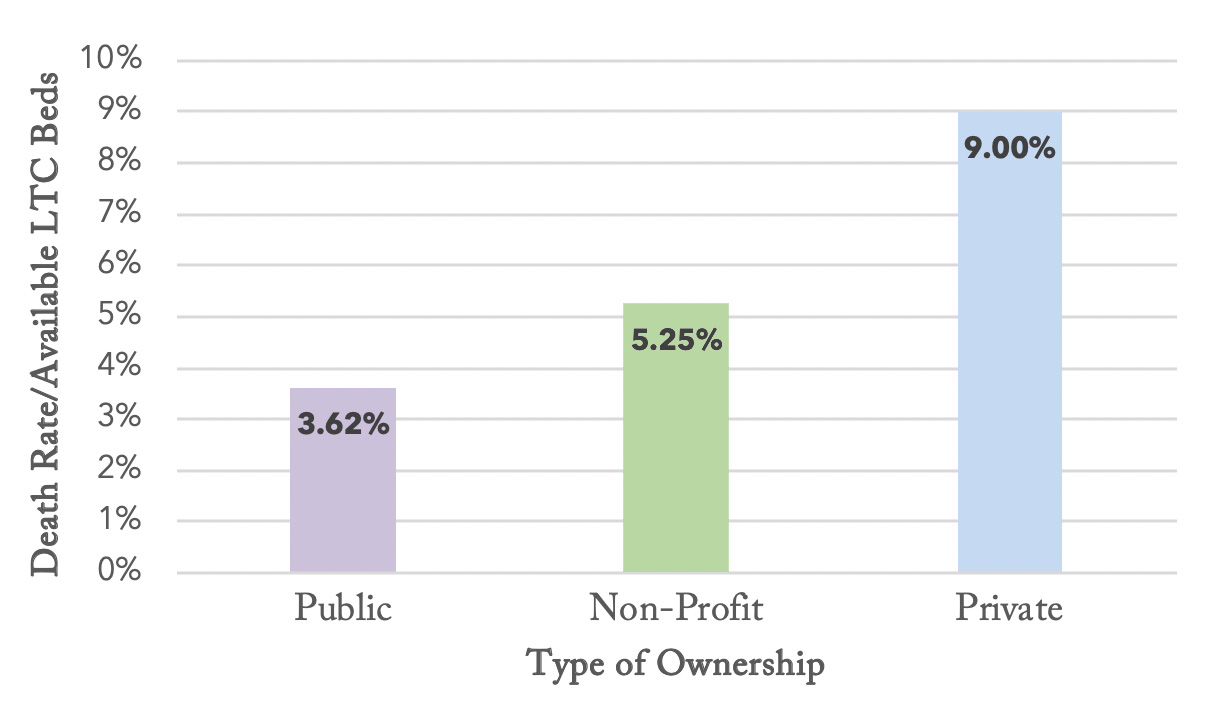

Similar LTC issues are faced in Ontario, and these have been further highlighted by the current COVID-19 crisis. LTC facilities are run by private or public companies, non-profit organizations or municipalities.41 These facilities must be licensed and funded by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Facilities can be privately run and owned, but the fees of individual residents are publicly funded, with some out-of-pocket costs or co-pays.42 Ontario’s current Progressive Conservative government cut funding to LTC facilities before the COVID-19 crisis. On April 21, 2020, the Ontario Health Coalition published an update on the ongoing crisis, stating that there have been outbreaks in 155 LTC homes, with 2,687 confirmed cases and at least 341 deaths.43 A report published by the Ontario Health Coalition on May 6, 2020, shows that the rate of COIVD-19 deaths in private care homes are double those in publicly funded homes (see Figure 3).44 Pat Armstrong and colleagues assert that Ontario’s push to privatize LTC is in direct contrast to evidence against increased private ownership of health services.45 Experts have offered their recommendations; the government should determine how to address them.

Figure 3: Ontario Death Rates per Total LTC Beds Available, by Type of Ownership

(Sources: Based on OLTCA data)

What’s Next?

In a letter addressed to Ontario’s LTC facilities, Deputy Minister of Long-Term Care Richard Steele writes, “while we have all been focused on managing emerging crisis situations, as the course of the pandemic evolves, it is essential that there is a clear focus on returning all homes to a state of staffing stability.”46 However, the claim that LTC facilities in Ontario had staffing stability before this crisis carries little merit. COVID-19 has highlighted the care crisis that was already occurring in Ontario, throughout Canada and across high-income nations, a crisis exacerbated by lack of regulation and increased private interests. With the problems of the sector clearly defined, governments are in a position to recognize and address the shift in priorities now needed to substantially improve the outcomes for LTC workers and residents.

It is important to begin by recognizing that increased involvement of private interests is detrimental to LTC. Private companies look to cut costs in order to increase their bottom line, and the biggest expense is labour. The squeeze on workers’ pay in this sector has resulted in poor working conditions and positions that are increasingly filled by marginalized and precarious workers. The squeeze on labour has contributed to the deterioration of care, as fewer workers are employed to deal with complex care needs, with less training and support. Armstrong and colleagues state that “the conditions of work are the conditions of care.”47 Addressing the needs of workers is thus a first step to tackling all LTC issues in Ontario.

The following recommendations, based on expert opinion and government commissioned reports, address the issues of labour and funding in the LTC sector.48 First, workers’ compensation in LTC facilities must be better regulated, ensuring that workers make a living wage that is commensurate with the valuable, difficult and labour-intensive work they perform. Second, LTC workers should be hired into permanent, full-time positions to allow workers access to employee rights and benefits, and to minimize the number of care workers employed at two or more LTC facilities. Third, care workers who enter the country as temporary migrants should be regularized, to allow them increased access to Canadian and provincial employee rights, and to minimize their vulnerabilities to employer exploitation. Finally, LTC should be deemed a medically necessary criteria under the Canada Health Act, in line with the recommendations proposed by the 2002 Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada (Romanow Commission).

Author’s Note

We would like to thank Araba Maanan Blankson, MIPP student at the BSIA, for research assistance.