Abstract

We conducted the current analysis to determine the potential role of measles vaccination in the context of the spread of COVID-19. Data were extracted from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Health Observatory data repository about the measles immunization coverage estimates and correlated to overall morbidity and mortality for COVID-19 among different countries. Data were statistically analyzed to calculate the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rho). There was a significant positive correlation between the vaccine coverage (%) and new cases per one million populations (rho = 0.24; p-value = 0.025); however, this correlation was absent in deaths per one million populations (rho = 0.17; p-value = 0.124). On further analysis of the effect of first reported year of vaccination policy, there was no significant correlation with both of total cases per one million populations (rho = 0.11; p-value = 0.327) and deaths per one million populations (rho = −0.02; p-value = 0.829). Claims regarding the possible protective effect of measles vaccination seem to be doubtful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

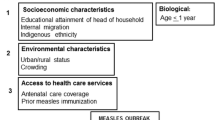

Even though researchers around the globe are working hard to provide helpful insights into the key features, pathogenesis, and treatment options for COVID-19 infection, it is deemed important to investigate other therapeutic options in addition to cross-protection of other vaccines. For instance, various researchers have hypothesized that live-attenuated vaccines such as rubella, measles, Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), and polio vaccines can result in cross-protection against severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Aaby and Benn 2017; Blok et al. 2015; De Bree et al. 2018; Higgins et al. 2014; Jensen et al. 2016). It was suggested that measles vaccine might be protective against COVID-19 based on the observation that the majority of infected patients in China were old, while a small number of patients were children (Salman and Salem 2020; Shereen et al. 2020). Since measles vaccination coverage in China from 2013 to 2018 was estimated to be 99% (Ma et al. 2019), it was hypothesized that measles vaccine might provide cross-resistance to COVID-19 infection.

Measles vaccination is done by live-attenuated, negative-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus monovalent vaccines or in combination with either of mumps and/or rubella vaccines (MMR) (WHO). MCV, being one of the most effective human vaccines, has been proven to exhibit optimal properties in terms of safety and efficacy. This vaccine is being produced on a large scale all over the world and distributed at a low cost via the Extended Program on Immunization (EPI). It provides life-long immunity against measles virus following one or two doses (Siani 2019).

In terms of universal vaccination policy coverage, various measles vaccination policies have been used in many countries with varying coverage rates. For instance, Italy accounted for > 30% of measles cases in the European Union since 2017 (Siani 2019). The mean MCV coverage rate is estimated to be 84.5%, based on the available data from 1980 to 2019. Furthermore, a great proportion of measles reported cases in 2016 were of unvaccinated individuals, with approximately 33% of them being 1–4 years old (Hung et al. 2018). On the other hand, significant progress has been noted in China in combat with the measles virus. During the period from 2013 to 2018, the MCV coverage rate was estimated to be 99% in China. Furthermore, the number of measles cases declined notably from 2015 to 2018 (31 versus 2.8 cases per 1 million populations, respectively) (Ma et al. 2019).

In general, live-attenuated vaccines result in specific immune responses towards the targeted pathogen. However, it has been suggested that MCV may also protect from other pathogens through the induction of a non-specific immune response, which in turn induce the innate immune system “Trained immunity” (De Bree et al. 2018). Based on a recent analysis, it was noted that the receipt of the measles vaccine standard titer was correlated with a reduction in all-cause mortality based on the analysis of four clinical trials and 18 observational studies (Higgins et al. 2016). This indicates that the implementation of MCV reduced the risk of all-cause mortality secondary to their non-specific effects on the diseases it prevents.

From the perspective of COVID-19 burden, both China and Italy were documented as the first two epicenters for the spread of COVID-19 infection, based on the World Health Organization reports. As of 18th April 2020, COVID-19 patients in China have a mortality rate of 5.60% compared to 13.19% mortality rate in Italy. Moreover, Italy had an higher number of COVID-19 cases compared to China (2852 versus 57 cases per million population) and also have higher mortality cases (376 versus 3 mortality cases per million populations) (Jousilahti et al. 1996).

Meanwhile, upon comparing MCV coverage rates from 2013 to 2018 in the two countries, we noted that China had a higher mean coverage of MCV compared to Italy (99% versus 89%) (Jousilahti et al. 1999). According to this profile, we hypothesize that the differences in MCV coverage rates among different countries may be attributable, to some extent, to the variation in COVID-19 spread. Therefore, we conducted the current analysis to determine if MCV had a protective effect on COVID-19 by identifying the association between MCV coverage rates and the number of confirmed cases and mortality rates of COVID-19 per million populations in different countries.

Methods

Data collection

Data were extracted from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Health Observatory data repository about the measles immunization coverage estimates (Marchioli et al. 2001). The coverage was estimated as “the percentage of children ages 12-59 months who received at least one dose of measles vaccine” (Matsumori et al. 2012). Data of COVID-19 total cases per one million populations and deaths per one million populations, for all possible countries, were obtained from the internet continuously updated repository “worldometers” on October 28th, 2020 (Jousilahti et al. 1999). Finally, the data were then merged according to the country to restore only countries having reported immunization coverage.

Statistical analysis

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rho) was used to determine the relationship between different variables (de Winter et al. 2016; Kumar et al. 2018). Data were analyzed using R software version 4.0.2 using the package (corrr). The statistical significance was considered when the P-value was < 0.05.

Results

Initially, we analyzed the correlation between measles vaccination coverage (%) and COVID-19 statistics in different countries (Table 1). There was a significant positive correlation between the vaccine coverage (%) and new cases per one million populations (rho = 0.24; p-value = 0.025); however, this correlation was absent in deaths per one million populations (rho = 0.17; p-value = 0.124) (Fig. 1; Fig. 2). On further analysis of the effect of first reported year of vaccination policy, there was no significant correlation with both of total cases per one million populations (rho = 0.11; p-value = 0.327) and deaths per one million populations (rho = −0.02; p-value = 0.829) (Fig. 3; Fig. 4). Another irrelevant significant correlation found between total cases and total death per one million populations (rho = 0.84; p-value < 0.001) (Table 1).

Discussion

COVID-19 which emerged in 2019 from the epidemic center in Wuhan city is causing respiratory manifestations ranges from mild to severe illness and up to mortality in severe cases of the disease (Zhou et al. 2020). The high infectious power of the virus where part of patients was presented in asymptomatic form has raised concerns among worldwide health centers towards it is prevention, treatment, and eradication (Bai et al. 2020). Several trials had emerged discussing multiple therapeutic agents and their efficacy in the treatment of the dangerous virus; however, the results of these trials were not promising and provide additional risks in COVID-19 patients from the dangerous side effects of the used drugs (Cao et al. 2020; Guastalegname and Vallone 2020).

Recent research suggests the role of vaccination in preventing, limiting the symptoms of COVID-19, and decreasing it is mortality. The epidemiological study of Miller et al. indicated a protective effect of Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination against COVID-19 (Miller et al. 2020). In our study, we found that measles vaccination did not provide a potential protective effect against COVID-19 affection nor it is mortality. Measles vaccination usually taken in combination with mumps and rubella vaccine with a first dose ranged from 9 to 12 months after birth while the second dose should be given at least after 1 month of the first dose according to World Health Organization report published in 2017 (mondiale de la Santé and Organization 2017). The measles vaccine has saved millions of lives each year (Koenig et al. 1990). Mina et al., in a population-based study, have demonstrated that measles vaccination provides a potential protective effect against some childhood infectious diseases (Mina et al. 2015).

Despite little is known regarding the pathophysiology of COVID-2019; however, the most adopted theory is the liberation of pro-inflammatory cytokines with the induction of lung injury in which so-called the cytokine storm (Huang et al. 2020). To our knowledge, measles vaccination is associated with immune activation and long-lived immunity against measles virus, however contradicting evidence regarding the promotion and suppression of T-helper cells and the liberated cytokines (Gans et al. 2019; Ovsyannikova et al. 2003). Besides, it has been suggested that MMR vaccine might reduce the severity of COVID-19 infection as a result of the sequence hemology between the fusion proteins of SARS-CoV-2 virus and measles and mumps, and the macro domains and rubella (Sidiq et al. 2020; Young et al. 2020). Moreover, Gold et al. reported that MMR might be protective against COVID-19 severity owing to the mumps portion while the measles and rubella portions showed no significant correlations (Gold et al. 2020). In an observational study, the authors reported that MMR vaccines were significantly associated with reduced COVID-19 infections; however, the study admitted that the results were biased and suggested conducting further randomized studies (Pawlowski et al. 2020). The study by Ashford et al. was the first to report the possible efficacy of measles vaccines against COVID-19 (Ashford et al. 2021). In the same context, Sumbul et al. reported that MMR vaccination can provide some protection against COVID-19 infection (Sumbul et al. 2021). Many hypotheses explain the absence of the association between measles vaccination and protection against COVID-19. Dine et al. indicated that the protective effect of the measles vaccine may last for approximately 26–33 years after the first dose (Dine et al. 2004), while COVID-19 is known to have more susceptibility and fatality of elderly populations who have a weak immune system and the risk further increased in the elderly associated with a comorbidities like diabetes and hypertension (Liu et al. 2020). Additionally, the COVID-19 behavior is still vague that is why some countries had high mortality like Italy and others have a low reported case fatality rate (Miller et al. 2020). Moreover, vaccine failure was reported in the literature (Hirose et al. 1997). Ogimi et al. also reported that the association was lost when adjustment of healthcare indices was done (Ogimi et al. 2020). Root-Bernstein was the first study that demonstrated a lack of significant correlation between MMR vaccination and the potential protection against COVID-19 (Root-Bernstein 2020a). In addition to reporting similar results, our findings can be considered more definitive as our sample was larger than theirs. Similarly, Kandeil et al. also supported our results by reporting that none of the childhood vaccines, including MMR, can be protective against COVID-19, and if they have any role, it will be attributable to another thing than providing anti-body-related immunity (Kandeil et al. 2020). Similar explanations were also suggested by Root-Bernstein study that showed that a potential similarity between MMR antigens and SARS-CoV-2 antigens (Root-Bernstein 2020b).

Our study should be interpreted with several limitations. Firstly, the age distribution of the included individuals was not available which constitutes a major issue regarding COVID-19 susceptibility and mortality. Secondly, the doses of measles vaccination were not applicable. Thirdly, the unavailability of comorbid illnesses in our sample may play a substantial role in the absence of the association between measles coverage and COVID-19 affection. Finally, our study fails to provide proper findings about the possibility of other vaccinations that are often given at the same time (or to the same groups of children) may confer some of the results that were observed in the present study, which was the case in previous studies (Pawlowski et al. 2020).

Conclusion

In conclusion, our analysis provides novel insight into the potential correlation between the coverage rates of measles vaccination coverage and the mortality rates/new cases of COVID-19 infection. There was no negative correlation on this aspect; making any allegation of the possible protective effect of measles vaccination seems unlikely. It should be noted that the data fail to provide proper findings about the possibility of other vaccinations that are often given at the same time (or to the same groups of children) may confer some of the results that were observed in the present study.

References

Aaby P, Benn CS (2017) Beneficial nonspecific effects of oral polio vaccine (OPV): implications for the cessation of OPV? Oxford University Press US

Ashford JW, Gold JE, Huenergardt MJA, Katz RBA, Strand SE, Bolanos J, Wheeler CJ, Perry G, Smith CJ, Steinman L, Chen MY, Wang JC, Ashford CB, Roth WT, Cheng JJ, Chao S, Jennings J, Sipple D, Yamamoto V, Kateb B, Earnest DL (2021) MMR vaccination: a potential strategy to reduce severity and mortality of COVID-19 illness. Am J Med 134:153–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.10.003

Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, Tian F, Jin D-Y, Chen L, Wang M (2020) Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA 323:1406–1407

Blok BA, Arts RJ, van Crevel R, Benn CS, Netea MG (2015) Trained innate immunity as underlying mechanism for the long-term, nonspecific effects of vaccines. J Leukoc Biol 98:347–356

Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, Liu W, Wang J, Fan G, Ruan L, Song B, Cai Y, Wei M, Li X, Xia J, Chen N, Xiang J, Yu T, Bai T, Xie X, Zhang L, Li C, Yuan Y, Chen H, Li H, Huang H, Tu S, Gong F, Liu Y, Wei Y, Dong C, Zhou F, Gu X, Xu J, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Li H, Shang L, Wang K, Li K, Zhou X, Dong X, Qu Z, Lu S, Hu X, Ruan S, Luo S, Wu J, Peng L, Cheng F, Pan L, Zou J, Jia C, Wang J, Liu X, Wang S, Wu X, Ge Q, He J, Zhan H, Qiu F, Guo L, Huang C, Jaki T, Hayden FG, Horby PW, Zhang D, Wang C (2020) A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382:1787–1799

De Bree L, Koeken VA, Joosten LA, Aaby P, Benn CS, van Crevel R, Netea MG (2018) Non-specific effects of vaccines: current evidence and potential implications. In: Seminars in immunology. Elsevier, pp 35–43

de Winter JC, Gosling SD, Potter J (2016) Comparing the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: a tutorial using simulations and empirical data. Psychol Methods 21:273–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000079

Dine MS, Hutchins SS, Thomas A, Williams I, Bellini WJ, Redd SC (2004) Persistence of vaccine-induced antibody to measles 26–33 years after vaccination. J Infect Dis 189:S123–S130

Gans H et al. 2019 2649. Measles-containing vaccination resulted in a balanced cytokine profile without evidence of immunosuppression in healthy 12-month-old children. In: Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

Gold JE, Baumgartl WH, Okyay RA, Licht WE, Fidel PL Jr, Noverr MC, Tilley LP, Hurley DJ, Rada B, Ashford JW (2020) Analysis of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) titers of recovered COVID-19 patients. mBio 11:e02628-02620. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02628-20

Guastalegname M, Vallone A (2020) Could chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine be harmful in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment? Clinical Infectious Diseases

Higgins J, Soares-Weiser K, Reingold A (2014) Systematic review of the non-specific effects of BCG, DTP and measles containing vaccines.

Higgins JP et al (2016) Association of BCG, DTP, and measles containing vaccines with childhood mortality: systematic review. bmj 355:i5170

Hirose M, Hidaka Y, Miyazaki C, Ueda K, Yoshikawa H (1997) Five cases of measles secondary vaccine failure with confirmed seroconversion after live measles vaccination. Scand J Infect Dis 29:187–190. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365549709035882

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395:497–506

Hung C-S, Chen Y-H, Huang C-C, Lin M-S, Yeh C-F, Li H-Y, Kao H-L (2018) Prevalence and outcome of patients with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with occluded “culprit” artery—a systemic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 22:34–34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-1944-x

Jensen KJ, Benn CS, van Crevel R (2016) Unravelling the nature of non-specific effects of vaccines—a challenge for innate immunologists. In: Seminars in immunology, vol 4. Elsevier, pp 377–383

Jousilahti P, Tuomilehto J, Vartiainen E, Pekkanen J, Puska P (1996) Body weight, cardiovascular risk factors, and coronary mortality. 15-year follow-up of middle-aged men and women in eastern Finland. Circulation 93:1372–1379. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.93.7.1372

Jousilahti P, Vartiainen E, Tuomilehto J, Puska P (1999) Sex, age, cardiovascular risk factors, and coronary heart disease: a prospective follow-up study of 14 786 middle-aged men and women in Finland. Circulation 99:1165–1172. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1165

Kandeil A, Gomaa MR, el Taweel A, Mostafa A, Shehata M, Kayed AE, Kutkat O, Moatasim Y, Mahmoud SH, Kamel MN, Shama NMA, el Sayes M, el-Shesheny R, Yassien MA, Webby RJ, Kayali G, Ali MA (2020) Common childhood vaccines do not elicit a cross-reactive antibody response against SARS-CoV-2. PLoS One 15:e0241471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241471

Koenig MA et al (1990) Impact of measles vaccination on childhood mortality in rural Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ 68:441

Kumar N, Kumar P, Badagabettu SN, Lewis MG, Adiga M, Padur AA (2018) Determination of Spearman correlation coefficient (r) to evaluate the linear association of dermal collagen and elastic fibers in the perspectives of skin injury. Dermatol Research Practice 2018:4512840–4512846. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4512840

Liu K, Chen Y, Lin R, Han K (2020) Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: a comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infection 80:e14–e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005

Ma C, Rodewald L, Hao L, Su Q, Zhang Y, Wen N, Fan C, Yang H, Luo H, Wang H, Goodson JL, Yin Z, Feng Z (2019) Progress toward measles elimination—China, January 2013–June 2019. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:1112–1116

Marchioli R, Avanzini F, Barzi F, Chieffo C, di Castelnuovo A, Franzosi MG, Geraci E, Maggioni AP, Marfisi RM, Mininni N, Nicolosi GL, Santini M, Schweiger C, Tavazzi L, Tognoni G, Valagussa F, GISSI-Prevenzione Investigators (2001) Assessment of absolute risk of death after myocardial infarction by use of multiple-risk-factor assessment equations: GISSI-Prevenzione mortality risk chart. Eur Heart J 22:2085–2103. https://doi.org/10.1053/euhj.2000.2544

Matsumori R, Shimada K, Kiyanagi T, Hiki M, Fukao K, Hirose K, Ohsaka H, Miyazaki T, Kume A, Yamada A, Takagi A, Ohmura H, Miyauchi K, Daida H (2012) Clinical significance of the measurements of urinary liver-type fatty acid binding protein levels in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Cardiol 60:168–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.03.008

(2020) Correlation between universal BCG vaccination policy and reduced morbidity and mortality for COVID-19: an epidemiological study. medRxiv

Mina MJ, Metcalf CJE, De Swart RL, Osterhaus A, Grenfell BT (2015) Long-term measles-induced immunomodulation increases overall childhood infectious disease mortality. Science 348:694–699

mondiale de la Santé O, Organization WH (2017) Measles vaccines: WHO position paper–April 2017–Note de synthèse de l’OMS sur les vaccins contre la rougeole–avril 2017 Weekly Epidemiological Record= Relevé épidémiologique hebdomadaire 92:205-227

Ogimi C, Qu P, Boeckh M, Bender Ignacio RA, Zangeneh SZ (2020) Association between live childhood vaccines and COVID-19 outcomes: a national-level analysis. medRxiv doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.17.20214510

Ovsyannikova IG, Reid KC, Jacobson RM, Oberg AL, Klee GG, Poland GA (2003) Cytokine production patterns and antibody response to measles vaccine. Vaccine 21:3946–3953. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00272-X

Pawlowski C et al. (2020) Exploratory analysis of immunization records highlights decreased SARS-CoV-2 rates in individuals with recent non-COVID-19 vaccinations. medRxiv:2020.2007.2027.20161976 doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.27.20161976

Root-Bernstein R (2020a) Age and location in severity of COVID-19 pathology: do lactoferrin and pneumococcal vaccination explain low infant mortality and regional differences? BioEssays 42:2000076. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.202000076

Root-Bernstein R (2020b) Possible cross-reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 proteins, CRM197 and proteins in pneumococcal vaccines may protect against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 disease and death. Vaccines 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8040559

Salman S, Salem ML (2020) The mystery behind childhood sparing by COVID-19. Int J Cancer Biomed Res 5:11–13

Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R (2020) COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res 24:91–98

Siani A (2019) Measles outbreaks in Italy: a paradigm of the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases in developed countries. Prev Med 121:99–104

Sidiq KR, Sabir DK, Ali SM, Kodzius R (2020) Does early childhood vaccination protect against COVID-19? Front Mol Biosci 7:120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2020.00120

Sumbul B, Sumbul HE, Okyay RA, Gülümsek E, Şahin AR, Boral B, Koçyiğit BF, Alfishawy M, Gold J, Tasdogan ALİM (2021) Is there a link between pre-existing antibodies acquired due to childhood vaccinations or past infections and COVID-19? A case control study. PeerJ 9:e10910. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10910

Young A, Neumann B, Mendez RF, Reyahi A, Joannides A, Modis Y, Franklin RJ (2020) Homologous protein domains in SARS-CoV-2 and measles, mumps and rubella viruses: preliminary evidence that MMR vaccine might provide protection against COVID-19. medRxiv:2020.2004.2010.20053207 doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.10.20053207

Zhou F, Yu T, du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B (2020) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395:1054–1062

Availability of supporting data

Data are available on request.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University through the Fast-track Research Funding Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RIA: contributed to the conception, analysis, writing the draft, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be responsible for the quality and accuracy of all parts of the work.

RMA: design of the work, the acquisition, interpretation of data, revised the draft, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be responsible for the quality and accuracy of all parts of the work.

RAA: contributed to the conception, interpretation of data, writing the draft, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be responsible for the quality and accuracy of all parts of the work.

FAK: design of the work, the acquisition, interpretation of data, writing the draft, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be responsible for the quality and accuracy of all parts of the work.

RHA: design of the work, analysis, revised the draft, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be responsible for the quality and accuracy of all parts of the work.

SGA: contributed to the conception, interpretation of data, writing the draft, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be responsible for the quality and accuracy of all parts of the work.

FAMA: design of the work, analysis, revised the draft, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be responsible for the quality and accuracy of all parts of the work.

MBG: contributed to supervision, the conception, interpretation of data, writing the draft, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be responsible for the quality and accuracy of all parts of the work.

MMA: contributed to supervision, the conception, interpretation of data, writing the draft, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be responsible for the quality and accuracy of all parts of the work.

MA: design of the work, analysis, revised the draft, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agreed to be responsible for the quality and accuracy of all parts of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Philippe Garrigues

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Altulayhi, R.I., Alqahtani, R.M., Alakeel, R.A. et al. Correlation between measles immunization coverage and overall morbidity and mortality for COVID-19: an epidemiological study. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28, 62266–62273 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14980-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14980-6