Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests used at the point-of-care, such as the Abbott Panbio, have great potential to help combat the COVID-19 pandemic. The Panbio is Health Canada approved for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in symptomatic individuals within the first 7 days of COVID-19 symptom onset(s). Symptomatic adults recently diagnosed with COVID-19 in the community were recruited into the study. Paired nasopharyngeal (NP), throat, and saliva swabs were collected, with one paired swab tested immediately with the Panbio, and the other transported in universal transport media and tested using real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). We also prospectively evaluated results from assessment centers within the community. For those individuals, an NP swab was collected for Panbio testing and paired with RT-PCR results from parallel NP or throat swabs. One hundred and forty-five individuals were included in the study. Collection of throat and saliva was stopped early due to poorer performance (throat sensitivity 57.7%, n=61, and saliva sensitivity 2.6%, n=41). NP swab sensitivity was 87.7% [n=145, 95% confidence interval (CI) 81.0–92.7%]. There were 1641 symptomatic individuals tested by Panbio in assessment centers with 268/1641 (16.3%) positive for SARS-CoV-2. There were 37 false negatives and 2 false positives, corresponding to a sensitivity and specificity of 86.1% [95% CI 81.3–90.0%] and 99.9% [95% CI 99.5–100.0%], respectively. The Panbio test reliably detects most cases of SARS-CoV-2 from adults in the community setting presenting within 7 days of symptom onset using nasopharyngeal swabs. Throat and saliva swabs are not reliable specimens for the Panbio.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Panbio (Abbott, IL, USA) is approved by Health Canada for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen in individuals who are within the first 7 days of symptom(s) onset. The immunochromatographic assay detects the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein and is indicated only for nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs. The test should be conducted either immediately after collection or up to 2 h if the NP swab is placed in the Panbio extraction tube filled with extraction buffer at room temperature [1].

Based on a study by Abbott that was conducted on 585 NP specimens collected from individuals exposed to SARS-CoV-2 or having COVID-19 symptoms within 7 days, sensitivity of the Panbio was found to be 91.4% and the specificity 99.8% when compared with a real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) reference method. Sensitivity increased to over 94% when samples with cycle threshold (Ct) >33 were excluded [1]. There is currently a paucity of data available from external third parties on the Panbio’s performance. Published studies, at the time of writing, have demonstrated Panbio sensitivity ranging from 72.6 to 86.5% among symptomatic individuals or exposed asymptomatic individuals [2–5].

We sought to assess the sensitivity of the Panbio by comparing its performance with RT-PCR testing among individuals in the community using two separate evaluations. The first by testing individuals with recently confirmed COVID-19 while adhering as closely as possible to manufacturer recommendations (testing of symptomatic individuals within 7 days of symptom(s) onset). The second setting was a prospective evaluation using the Panbio to detect SARS-CoV-2 among individuals presenting to community COVID-19 assessment/screening centers. We also tested the accuracy of the Panbio with samples taken from asymptomatic individuals at low risk for COVID-19 (i.e. no exposures) and on retrospective clinical samples previously positive for common respiratory pathogens.

Methods

Testing individuals with known COVID-19

Individuals residing within the Calgary and Edmonton Health Zones of Alberta, Canada, who recently tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at Alberta Precision Laboratories (APL; AB, Canada) and confirmed as cases by Alberta Health Services (AHS; AB, Canada) Public Health were recruited. Diagnostic testing was performed by a Health Canada approved SARS-CoV-2 assay or a lab developed RT-PCR assay (see below for details). Participants were identified by an AHS Public Health confirmed case list. Oral consent by phone was obtained to collect samples in the participant’s home. At the time of consent the symptoms of the individual were recorded (usually within 24 h of collecting study swabs). Individuals under the age of 18, or in supportive or congregate living facilities were excluded. Eligible individuals who consented to the study were recruited to have two NP swabs, two throat swabs, and a saliva sample collected by trained healthcare professionals. The University of Calgary Research Ethics Board (Calgary, AB, Canada) approved this study (REB20-444).

Healthcare workers, previously trained in NP and throat swab collection, were given instructions on how to collect swabs from recruited COVID-19 infected individuals. For reference RT-PCR testing, the YOCON NP swab and universal transport media (UTM) (Yocon, Beijing, China) and ClassiqSwabs for throat in COPAN UTM-RT (COPAN Diagnostics, CA, USA) were used [6]. For Panbio testing, the NP swab provided in the Panbio testing kits (Abbott) was used, and the ClassiqSwab was used for collecting throat and saliva samples. NP swabs were collected from separate nostrils. Throat swabs were collected from both sides of the oropharynx and the posterior pharyngeal wall under the uvula. Throat swabs were collected approximately 1 minute apart, and collectors were asked to alternate the order in which throat swabs were collected. Saliva was collected by having the individual place a ClassiqSwab (COPAN) within their mouth for approximately 30 seconds to allow saliva to pool onto the swab. The swab was then immediately tested on the Panbio cartridge.

For each paired NP and throat swab, one was tested immediately on the Panbio cartridge for testing and the other was placed into UTM for RT-PCR testing. Saliva samples tested on the Panbio were compared with throat swabs sent for RT-PCR testing. Throat and NP swabs in UTM collected for RT-PCR testing were stored at 4°C upon arrival at the laboratory and tested within 72 h of collection. RT-PCR testing included an assay targeting the E-gene of SARS-CoV-2 developed within our laboratory (Public Health Laboratory, APL), and the Cobas® SARS-CoV-2 test on the Cobas 6800 instrument run according to the manufacturer’s instructions [7]. For the E gene RT-PCR, 200 ul of UTM were extracted on the MagMAX Express-96 or Kingfisher Flex, (ABI) using the MagMAX-96 Viral RNA Isolation Kit (ThermoFisher) or the PurePrep Pathogen Kit (MolGen) according to manufacturer’s instructions, and eluted into a volume of 110 ul.

For our lab-developed test, the samples were considered positive for SARS-CoV-2 when E gene cycle threshold (Ct) value was <35. If the Ct was ≥35, amplification from the same eluate was repeated in duplicate and was considered positive if at least 2/3 results had a Ct <41. For the Cobas SARS-CoV-2 test, as per the manufacturer, a positive result was defined as 2/2 targets positive, or 1 or more targets were positive in duplicate. If 1/2 targets were positive and duplicate testing was negative, the result was considered indeterminate.

For discrepant results (Panbio positive, RT-PCR negative), the swabs in UTM were reextracted and retested in triplicate with the N2 assay from the US CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) real-time RT-PCR diagnostic panel using the UltraPlex 1-Step Toughmix (Quantabio, MA, USA) and on the Cobas 6800 [8].

Sensitivity and Cohen’s κ statistic was calculated with Clopper-Pearson 95% confidence intervals. Statistical analysis was performed using Pearson Chi-squared for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables using STATA (version 14.1).

Negative samples and exclusivity panel

Two NP swabs were collected from asymptomatic individuals at low risk of having COVID-19 (no recent travel, no exposures). One swab was tested immediately on the Panbio testing cartridge. The other swab was tested by RT-PCR, as explained above. To assess for cross-reactivity, retrospective samples containing various respiratory viruses, stored in UTM at −80°C, were tested by aliquoting 3 drops of sample into the Panbio testing cartridge. These samples were previously detected by the NxTAG® Respiratory Pathogen Panel (Luminex, TX, USA) or the CDC influenza A/B multiplex assay [9]. The ability of the Panbio to process this volume of UTM was confirmed by testing retrospective positive SARS-CoV-2 samples, in UTM, and showing that they could be detected (data not shown; only samples with Ct <25 were detectable on the Panbio).

Prospective testing of individuals with suspected COVID-19

After the first clinical evaluation, a pilot implementation was conducted with individuals presenting to AHS community COVID-19 assessment centers in Edmonton and Calgary that were staffed by AHS nurses. These are the primary locations for community patients not needing medical attention to get tested for COVID-19 in Alberta. Upon presentation to the assessment center, individuals who had symptoms and were within 7 days of symptom(s) onset were asked if they would like to receive Panbio testing or routine testing alone. Those receiving routine testing alone were not included in the analysis. For each individual who agreed to Point of Care Testing (POCT) with the Panbio, two NP swabs from different nostrils were collected. The first NP swab taken was placed in UTM for RT-PCR and the second was used for Panbio testing, to ensure all individuals had a sample available for RT-PCR (i.e. in case the individual refused the second NP or throat swab). A minority of individuals had throat swabs in UTM sent for RT-PCR due to the individual refusal of having two NP swabs taken. Panbio testing occurred on site within 10 minutes by trained assessment center staff as per manufacturer instructions. If an individual had a negative Panbio test, the first swab was sent for confirmatory testing to an APL laboratory for RT-PCR testing. If an individual had a positive Panbio test, the first swab was sent to an APL laboratory for storage at -80oC, as positive Panbio results were considered true positives and did not require confirmation. These positive samples were tested offline at a later date for surveillance purposes. The RT-PCR testing was performed on the APL E-gene PCR or on a Health Canada/FDA-approved commercial assay. Commercial assays were site specific and included the Allplex (Seegene, Seoul, South Korea), BDMax (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA), Panther Fusion (Hologic, MA, USA), GeneXpert (Cepheid, CA, USA), and Simplexa (DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy). Discrepant results (Panbio positive, RT-PCR negative) were retested in triplicate, as explained above.

Results

Testing individuals with known COVID-19

One hundred and sixty-three individuals were recruited for the first clinical evaluation. Eighteen individuals were excluded: Three were asymptomatic at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis and at time of study recruitment, nine were symptomatic at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis but asymptomatic at the time of study recruitment, four had Panbio results that were not recorded, one had the Panbio reported as negative before 15 minutes, and another was unable to be processed by RT-PCR. Individual characteristics of the remaining 145 individuals is provided in Table 1.

Cough was the most frequent symptom at enrollment (42.8%), followed by headache (42.1%), myalgias (41.4%), sinus congestion (36.6%), malaise (31.0%), pharyngitis (29.0%), fevers/chills (28.3%), anosmia (24.1%), ageusia (24.1%), rhinorrhea (20.0%), shortness of breath (5.5%), nausea/vomiting (3.4%), and other (17.9%, included chest pain, diarrhea, eye soreness, lymphadenopathy, loss of appetite, arthralgia, dizziness, and/or conjunctivitis). The mean duration of symptoms at the time of collection was 6.1 days (median 6.0, range 3.0–10.0 days). Ninety-one percent of individuals were within the 7 day symptom onset window. The mean E-gene Ct value for positive results from RT-PCR was 24.7 (median 24.8, range 15.9–37.9).

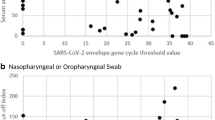

Throat and saliva sample collection was terminated early in our study due to poor sensitivity compared to NP; therefore, only 61 and 41 individuals had a throat and saliva sample taken, respectively. The sensitivity of throat and saliva swabs was 57.7% [95% confidence intervals (CI) 43.2–71.3%] and 2.6% (95% CI 0.06–13.5%), respectively (Fig. 1). In terms of swab collection order, 70.0% of individuals had throat swabs destined for Panbio testing collected before the throat swab destined for RT-PCR. In addition, 14.6% of swabs used for saliva testing on the Panbio were collected before both Panbio and RT-PCR throat swabs. The remaining 85.4% of swabs collected for saliva testing were collected last.

Of the 145 individuals that underwent a NP swab, 80.7% had the NP swab for Panbio testing collected first, followed by the NP swab for RT-PCR in the opposite nostril. Out of 145 paired NP samples, 121 were positive on both the Panbio and RT-PCR (Table 2). The sensitivity of the Panbio compared with RT-PCR was 87.7% (95% CI 81.0–92.7%) (Fig. 1). Specificity was 71.4% (95% CI 29.0–96.3%) with a total of 5 true negative results. There were 17 false negatives on the Panbio, with 14/17 (82.4%) having a Ct > 25 by RT-PCR and 9/17 (52.9%) with Ct > 30 on RT-PCR (Supplementary material). Two false negative samples were from individuals outside the 7 day symptom onset window. Restricting the analysis to individuals with symptom onset ≤ 7 days did not significantly change the sensitivity of the Panbio, which was 88.1% (95% CI 81.1–93.2%) for this group. Panbio positive samples had lower Ct values on RT-PCR testing than Panbio negative samples (p<0.001; Table 3). All samples (n=7) with a Ct value ≥ 33 were negative on the Panbio.

When tested in triplicate using RT-PCR followed by triplicate testing by the CDC method and testing on the Cobas 6800, neither of the two RT-PCR negative samples, with paired positive Panbio samples, resolved as positive.

Prospective testing of individuals with suspected COVID-19

There were 1641 symptomatic individuals tested on the Panbio in community assessment centers from December 7–21, 2020, with 268/1641 (16.3%) positive for SARS-CoV-2. Individual participant characteristics are provided in Table 4. There were 37 false negatives and 2 false positives, corresponding to a sensitivity of 86.1% (95% CI 81.3–90.0%) and a specificity of 99.9% (95% CI 99.5–100.0%), respectively. Cohen’s κ statistic is 0.91 (95% CI 0.88–0.94). Of the 37 false negative samples, 23 were positive on the Allplex, 6 on the Panther, and 8 on the Cobas. Of the 23 samples positive on the Allplex, 7 had E-gene Ct<20, 4 had Ct 20–25, 3 had Ct 25–30, 5 had Ct >30, and 4 required repeat testing as only 1 of the 3 targets were initially positive (Ngene or RdRp, all with Ct > 35). Repeat testing of the two RT-PCR negative, Panbio positive samples did not identify presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA.

On average, it took 2.7 h for the Panbio test result to be reported, compared to 17.6 h for the RT-PCR test. The short delay in Panbio test result reporting is related to the fact that our Panbio results had to first be scanned and emailed to a centralized laboratory location for data entry.

Negative samples and exclusivity panel

Twenty asymptomatic individuals at low risk of COVID-19 were tested by POCT, all of which were negative on the Panbio and RT-PCR. All 11 retrospective samples containing other respiratory viruses tested were negative. These samples were previously positive for one of either human metapneumovirus, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus type 4, other coronavirus (HKU1, NL63), enterovirus/rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza A H3N2, influenza A H1N1, or influenza B.

Discussion

The initial community clinical study and the evaluation post-implementation by POCT at community assessment centers demonstrated similar sensitivity. Overall, the sensitivity of the Panbio was moderate at 86.1–87.7% compared with various RT-PCR platforms for this population. This study demonstrates that acceptable sensitivity is achieved for clinical use with the Panbio, but confirmatory testing of negatives is likely necessary for most populations.

The use of rapid antigen tests, such as the Panbio, for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 among symptomatic individuals within the community remains a worthwhile endeavor. Although confirmatory testing of negatives is recommended, identifying positives at the point of care has several advantages. It can speed important public health measures, such as contact tracing and isolation. Moreover, it has significant benefits for the laboratory in terms of decreasing error and improving laboratory processes. For instance, decreasing the number of positive samples entering the laboratory can decrease the risk of false positive results by reducing the probability of SARS-CoV-2 contamination during RT-PCR testing. In addition, the decrease in positive samples can improve efficiencies in other laboratory processes, such as pooling.

While there were two instances in our initial clinical evaluation of known COVID-19 individuals where the Panbio was positive and the RT-PCR was negative, we believe these are true positives based on several reasons. Participants recruited in our study were all recently diagnosed with COVID-19; none of the samples from the asymptomatic individuals at low risk of COVID-19 gave false positive results throughout the study; and no issues with false positive results have been identified by the Panbio manufacturer or among previous Panbio publications within the literature when used on symptomatic individuals [2–5]. Most likely, the two false negative results from RT-PCR was related to differences in sample collection among individuals with low SARS-CoV-2 virus load present.

The sensitivity of the Panbio varies in the literature from 72.6 to 86.5% among individuals with symptoms ≤ 7 days [2–5]. These studies varied in terms of their study design and reference standards used. All studies examined paired NP swabs tested with the Panbio and a PCR-based platform, with two of the four studies using the Allplex (Seegene, South Korea) [3, 4]. One study [2] used the VitaPCR SARS-CoV-2 (Credo diagnostics, Singapore) that has limited data available on its performance, which may explain why 7 samples were Panbio positive but VitaPCR SARS-CoV-2 negative [10]. Gremmels et al. performed testing on the Panbio up to 2 h from collection, which may account for the lower sensitivity detected (72.6%) [3]. Of the studies that examined positivity rate based on symptom duration, one study found no difference in positivity rate with duration of symptom onset [3], another found higher sensitivity in individuals with symptom onset < 7 days (sensitivity 86.5%) compared with individuals with symptom onset ≥ 7 days (sensitivity 53.8%) [4], and another found slightly higher sensitivity in individuals with symptoms < 5 days (sensitivity 80.4%) compared with individuals with symptoms ≤ 7 days (79.6%) [5]. We found no difference in Panbio sensitivity among individuals with symptoms > 7 days, but this was limited to a very small number of samples (n=15). All studies, including ours, found decreases in Panbio sensitivity among SARS-CoV-2 samples with higher Ct values, with sensitivity dropping when Ct values are approximately > 26.

Our study contributes to the literature on the Panbio’s performance by using alternative collection methods, such as throat and saliva swabs. Unfortunately, these specimens were proven to be inferior to NP swabs and should not be used on the Panbio. Further studies are required to determine if an alternative way to test saliva on the Panbio could prove effective (e.g. direct inoculation of saliva onto the Panbio test cartridge or saliva collected in a media). We did not evaluate nasal swabs on the Panbio because the results could have been affected by the concurrent collection of paired NP swabs. However, previous work done by our laboratory has shown nasal swabs to be inferior to throat swabs for the detection of SARS-CoV-2, so it would be surprising if nasal swabs proved to be as effective a specimen as NP swabs for testing on the Panbio [11].

Our study was predominately restricted to individuals within the community who had symptoms ≤ 7 days. As such, our study was unable to provide any conclusions about the Panbio performance among individuals admitted to hospital, in congregate living facilities, who are asymptomatic, and individuals with symptoms > 7 days. The strengths of our study include the large number of COVID-19 positive individuals recruited. In addition, we included prospective data taken from clinical settings (symptomatic individuals presenting to COVID assessment centers) and found similar results, which further reinforces the findings of our study. We also tested asymptomatic individuals at low risk of COVID-19 (no travel, no exposure) and tested retrospective samples positive for other respiratory viruses.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the Panbio was able to detect most SARS-CoV-2 positive samples among individuals with symptomatic COVID-19 infection. However, it will miss at least 10% of people with confirmed COVID-19 infection, and therefore, negative results on the Panbio obtained from individuals at high risk for COVID-19 infection should be considered presumptive until confirmed with a PCR test. Given the speed, low-complexity and acceptable performance, the Panbio test is suitable for use in the POCT setting, especially when rapid identification of positive patients is critical. As such, they will play an impactful role in combating the COVID-19 pandemic by improving testing in settings where rapid turnaround times are much needed, such as among difficult to reach populations (e.g. homeless), in high throughput COVID-19 assessment centers, and in rural areas where access to a laboratory is limited.

References

Abbott. Panbio: COVID-19 Ag rapid test device. 2020. [Accessed Dec 25, 2020]. Available at: https://www.who.int/diagnostics_laboratory/eual/eul_0564_032_00_panbi_covid19_ag_rapid_test_device.pdf.

Fenollar F, Bouam A, Ballouche M et al (2020) Evaluation of the Panbio Covid-19 rapid antigen detection test device for the screening of patients with Covid-19. J Clin Microbiol 59:e02589–e02520

Gremmels, et al. Real-life validation of the Panbio COVID-19 antigen rapid test (Abbott) in community-dwelling subjects with symptoms of potential SARS-CoV-2 infection. MedRxiv. 2020. [Accessed Dec 25, 2020]. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.16.20214189v1.

Linares M, Pérez-Tanoira R, Carrero A et al (2020) Panbio antigen rapid test is reliable to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 infection in the first 7 days after the onset of symptoms. J Clin Virol. 133:104659

Albert E, Torres I, Bueno F et al (2020) Field evaluation of a rapid antigen test (Panbio™ COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device) for COVID-19 diagnosis in primary healthcare centers. Clin Microbiol Infect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.11.004

Berenger BM, Conly JM, Fonseca K, et al. (2020) Saliva collected in universal transport media is an effective, simple and high-volume amenable method to detect SARS-CoV-2. Clin Microbiol Infect. S1198-743X(20)30689-3

Pabbaraju, et al. Development and validation of reverse transcriptase-PCR assays for the testing of SARS-CoV-2. JAMMI. 2020. Available at: https://jammi.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jammi-2020-0026. Accessed 25 Dec 2020

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) real-time RT-PCR diagnostic panel: For Emergency Use Only: Instructions for Use [Accessed Nov 30, 2020]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/134922/download.

Selvaraju S, Selvarangan R (2009) Evaluation of three influenza A and B real-time reverse transcription-PCR assays and a new 2009 H1N1 assay for detection of influenza viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 48(11):3870–5

Fournier PE, Zandotti C, Ninove L et al (2020) Contribution of VitaPCR SARS-CoV-2 to the emergency diagnosis of COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 133:104682

Berenger B, Fonseca K, Schneider AR, Hu J, Zelyas N (2020) Sensitivity of nasopharyngeal, nasal and throat swab for the detection of SARS-CoV-2. MedRxiv. 2020. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.05.20084889. Accessed 25 Dec 2020

Acknowledgements

We thank the AHS mobile integrated health team for collecting samples in the community and Alberta Precision Laboratory staff for assistance with testing of samples and in the development and support of the POCT program.

Availability of data

Available upon request.

Funding

This work was funded using internal operating funds of Alberta Precision Laboratories and Alberta Health Services. Test kits and instruments were paid for by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stokes, W., Berenger, B.M., Portnoy, D. et al. Clinical performance of the Abbott Panbio with nasopharyngeal, throat, and saliva swabs among symptomatic individuals with COVID-19. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 40, 1721–1726 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-021-04202-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-021-04202-9