Abstract

As SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are deployed worldwide, a comparative evaluation is important to underpin decision-making. We here report a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of Phase I/II/III human trials and non-human primates (NHP) studies, comparing reactogenicity, immunogenicity and efficacy across different vaccine platforms for comparative evaluation (updated to March 22, 2021). Twenty-three NHP and 32 human studies are included. Vaccines result in mostly mild, self-limiting adverse events. Highest spike neutralizing antibody (nAb) responses are identified for the mRNA-1273-SARS-CoV and adjuvanted NVX-CoV2373-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. ChAdOx-SARS-CoV-2 produces the highest T cell ELISpot responses. Pre-existing nAb against vaccine viral vector are identified following AdH-5-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, halving immunogenicity. The mRNA vaccines depend on boosting to achieve optimal immunogenicity especially in the elderly. BNT162b2, and mRNA-1273 achieve >94%, rAd26/5 > 91% and ChAdOx-SARS-CoV-2 > 66.7% efficacy. Across different vaccine platforms there are trade-offs between antibody binding, functional nAb titers, T cell frequency, reactogenicity and efficacy. Emergence of variants makes rapid mass rollout of high efficacy vaccines essential to reduce any selective advantage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Three novel coronaviruses (HCoV) have crossed into humans during the 21st century. Severe acute respiratory syndrome 1 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) emerged in China in 2002/3, with 8096 infections and about 10% case fatalities1. In 2012, a SARS-like disease emerged in Saudi Arabia, termed Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)2, sporadic outbreaks leading to 2519 infections and a case fatality rate of 35%3. The knowledge accrued in relation to protective immunity and vaccinology of SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV is pertinent to decoding the principles of protection from the highly related SARS-CoV-2.

Various vaccine candidates were developed following the emergence of SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV, with live-attenuated, DNA, and recombinant viral vectors investigated4,5,6. With an animal model in place, advances in vector design and greater knowledge of disease pathogenesis, there was significant pre-clinical and clinical research towards an effective MERS-CoV vaccine6. One MERS-CoV vaccine candidate lowered viral shedding in the dromedary camel reservoir7. Development of SARS-CoV-1 vaccines began during the outbreak, but subsided as the threat of a major pandemic decreased8.

With respect to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, there has been unprecedently rapid vaccine development: the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna mRNA vaccines and the Astra Zeneca/Oxford ChadOx vaccines are widely rolled-out in several countries as well as some countries utilizing the Chinese Sinovac inactivated SAR-CoV-2 and Russian Sputnik V adenovirus vaccines, and over 300 candidates at different stages of development, utilizing diverse platforms, including protein subunit with adjuvant, non-replicating viral vectors, RNA, virus-like-particles (VLP), DNA, inactivated- and live-attenuated virus9,10. An ideal vaccine is one that can be produced at scale and low cost, is safe, easy to distribute and store, induces strong, protective neutralizing antibody and T cell responses, ideally with a single dose, elicits a durable response that does not recapitulate the waning antibody (Ab) titers seen following natural coronavirus infection, and should be equally suitable for very young, old and immunosuppressed individuals11. It should also be technically modifiable to accommodate improving efficacy against emerging variants. To achieve these deliverables in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, several vaccines may be required. Following an initial period awaiting trial results of vaccine candidates, we have entered a period now in which the public, policy-makers and researchers start to consider detailed, comparative questions raised by the extraordinary, real-life challenges of mass vaccination roll-out during an ongoing, global, pandemic. This has focused greater attention on dosing and boost intervals and the quality, quantity and durability of immune responses, as well as details of the adverse event (AE) profile. Past coronavirus vaccine research has highlighted potential safety concerns related to antibody (Ab)-dependant enhancement (ADE) and induction of Th2-associated lung immunopathology following viral challenge12,13.

At a time of intense vaccine development across many diverse platforms, there is an incentive to address the need for a comprehensive appraisal benefiting from experience from coronavirus vaccine trials. The investigated approaches encompass different advantages and disadvantages with respect to immunogenicity, efficacy, durability of immunity, safety profile and ease of manufacture, yet there has thus far been relatively little side-by-side evaluation. The aim here was to evaluate pertinent SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 studies in humans and NHP published up to the March 22, 2021. In the context of the current pandemic this is pertinent to structuring rational, comparative appraisal and selection of the most practical and effective SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

Results

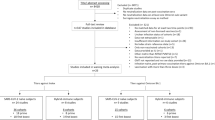

Study selection followed PRISMA guidelines (Fig. 1). A search of PubMed and EMBASE databases used pre-determined search criteria, initially generating 5945 studies (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Duplicates, in vitro studies and studies using other animal models were not taken forward. Searches by ‘Title and Abstract’ yielded a total of 55 articles updated to March 22, 2021. Thirty-two human14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45 and 23 NHP46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68 studies about vaccines against SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are reviewed (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Individual vaccines are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 5. The greatest focus of research activity was in China and the USA (Supplementary Fig. 1). The mean age in human trials was 42.7 years. The gender distribution in human vaccine groups was roughly equal. Vaccine group ethnicity was skewed as follows: 72.8% of participants were White, 11.2% Hispanic, 7.2% Black/African American and 3.9% Asian (Supplementary Table 6).

There were many different vaccine platforms used, the most frequent being viral vector platforms, followed by nucleic acid (mRNA/DNA) and inactivated virus platforms. Excluding the inactivated vaccine platforms, the predominant antigen insert employed was a variant of, or the full length, spike protein—the defined nAb target. The vast majority of vaccine schedules use a 2-dose prime/boost protocol, with the interval between doses ranging from 14 to 84 days and boost at day 21 being the most commonly reported protocol (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 3–5).

Antibody binding studies were largely carried out by ELISA-IgG in NHP and human vaccine studies. One NHP study used ELISA-IgA to evaluate mucosal immunity59. Antigens used for IgG detection in humans trials were spike GP, spike RBD and trimeric spike GP. T cell analysis was primarily by IFNγ ELISpot or by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS), generally using overlapping peptide pools for spike antigen. We have not attempted a cross-comparison between these two readouts to arrive at a universal comparison of spike-specific responder cell frequency since differential strategies for CD4/CD8 gating in ICS impose a confounder.

Of the five published human studies evaluating vaccine efficacy, the Polack31, BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and Baden27, mRNA-1273 (Moderna vaccine) vaccines showed the highest efficacy at greater than 94.6% followed by the Logunov17, rAd26/rAd5 vaccine at 91.6% efficacy. The Voysey21,22, ChAdOx (Astra Zeneca/Oxford Vaccine) demonstrated efficacy of 70.4% and 66.7% in two pooled efficacy studies (Supplementary Table 7). For efficacy and safety analysis of vaccine candidates tested in NHP studies, histopathology, biochemical analysis, clinical and radiological evaluations were most often used, along with RT-PCR measure of viral load (Supplementary Tables 4 and 8).

Adverse events

NHP safety analysis was described in seven studies (Supplementary Table 8). There were few notable changes in biochemical, hematological or clinical signs in the majority of NHP vaccine groups. Four studies evaluated ADE risk49,50,54,58, suggested to be a risk factor in HCoV vaccine safety, and none of the studies found evidence of ADE. No significant Th2 pathology was found in any NHP analysis.

Safety analysis of local and systemic AE were recorded across all 32 human studies. Figure 2 shows a comparative Forest plot analysis of the incidence of AE across published human studies looking at the relative risk in vaccine compared to control groups. Overall, there is a 1.7-fold increased risk of any AE in the vaccinated compared to control groups. There was a 4.1-fold increased risk in Polack31, BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine and a 1.8-fold increased risk in the Baden27, mRNA-1273 vaccine (Fig. 2). The vast majority of reported AE were in the mild local and systemic category.

A risk ratio of >1 is indicative of a higher incidence of AE in experimental compared to control groups. A Mantel–Haenszel variance random effects model (CI) was employed to estimate effects between experimental and control groups correcting for confounding variables. I2 statistic, 95% CI and point estimates are displayed for each individual study.

In terms of mild or moderate local AE, the most commonly reported local AE was injection site pain, followed by redness and swelling (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 9). Martin DNA-SARS-CoV-143, Modjarrad DNA-MERS-CoV45, Baden/Jackson/Anderson/Chu mRNA-1273-SARS-CoV-224,25,26,27, Walsh/Mulligan/Pollack BNT162b1/2-SARS-CoV-228,29,31, Logunov rAd26/rAd5-SARS-COV-216,17 and Folegatti/Ramasamy, SARS-CoV-2 ChAdOx19,20 and Keech NVX-CoV237339 vaccines all reported a high percentage of subjects with injection site pain. Koch MERS-CoV42 and Martin DNA-SARS-CoV-143 reported the highest incidence of local redness and swelling.

In terms of mild or moderate systemic AEs, the most commonly reported were headache, fever, myalgia, chills and fatigue (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 10). They were reported for most vaccine platforms, including BNT162b1/2-SARS-CoV-228,29,31, mRNA-1273-SARS-CoV-224,25,26,27, SARS-CoV-2 ChAdOx19,20, NVX-CoV237339 and rAd26/rAd5-SARS-COV-2 (Sputnik V)16,17 vaccines. There is increased frequency of mild/moderate systemic AE events with increased dose and at the boost of a prime boost schedule seen in the RNA vaccines Baden/Jackson/Anderson mRNA-1273-SARS-CoV-224,25,27, and Walsh/Mulligan/Pollack BNT162b1/2-SARS-CoV-228,29,31, and Keech, NVX1273-Cov39 vaccines with increased incidence of headache, myalgia, arthralgia and fatigue after boosting. Analysis of individual local and systemic AE is available in Figs. 3 and 4 and Supplementary Tables 9 and 10.

Several of the clinical trials included in this systematic review recorded grade three AE related to vaccine or placebo (Supplementary Fig. 2). Baden27, mRNA-1273 showed the highest percentage of grade 3 AE (11%) following boost. Zhu14,15, AdH5, Keech39, NVX-CoV2373, Sadoff18, Ad26.CoV2.S, Mulligan/Walsh28,29 BNT162b1/2 and Folegatti23, ChAdOx all reported grade 3 AE in more than 3.5% of participants.

The occurrence of reported solicited and unsolicited serious AE following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the published studies to date was low with similar reporting in vaccine and control groups at 0.6% in each (Baden27, mRNA-1273); 0.6% vaccine and 0.5% control (Pollack31, BNT162b2); 0.7% vaccine and 0.8% control (Voysey21, ChAdOx) and 0.3% vaccine and 0.4% control (Logunov17, rAd26/rAd5) (Supplementary Table 11).

Autonomic nervous imbalance, nausea, vomiting, rheumatoid arthritis, dyspnea, swollen face and peripheral edema were reported in the vaccine group of Baden, mRNA-127327. Transverse myelitis and fever were recorded in the experimental arm of Voysey, ChAdOx-SARS-CoV-221. Shoulder injury related to vaccination, right axillary lymphadenopathy, paroxysmal ventricular arrhythmia and right leg paresthesia were recorded in the Polack, BNT162b2-SARS-CoV-231.

Antibody responses

Interstudy analysis of ELISA-IgG GMT was conducted across published human studies14,15,16,17,18,19,20,23,24,25,28,29,30,32,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,45. A number of conclusions can be drawn regarding overall titer and the dose-dependent and boost dependent nature of ELISA-IgG Ab responses (Fig. 5).

Blue = low; black = intermediate; red = high dose of vaccine indicated. Antibody titre recorded circa 28 days post injection. Log transformed scale used. Vp viral particles, RBD receptor binding domain, GMT geometric mean titre, CI confidence interval, S2-P SARS-CoV-2 GP with transmembrane anchor and intact S1-S2 cleavage site, S1 S1 spike glycoprotein domain, GMET geometric mean endpoint titre, EU ELISA unit, IQR interquartile range. (1A) Zhu, AdH-5, Phase 1: low dose—5 × 1010 vp, intermediate dose—1 × 1011 vp, high dose —1.5 × 1011 vp; RBD; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (2A) Zhu, AdH-5, Phase 2: low dose—1 × 1011 vp, high dose—5 × 1010 vp; RBD; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (3A) Logunov, rAdH26/rAd5-Lyo: lyophilised formulation. Unspecified dose—1011 vp; Prime-Boost; RBD; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (4A) Logunov, rAdH26/rAd5-Vac: frozen formulation. Unspecified dose—1011 vp; Prime-Boost; RBD; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (5A) Logunov, rAdH26/rAd5-Vac Phase 3 trial: unspecified dose—1011 vp; post boost in a Prime-Boost; RBD; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (6A-F) Sadoff, Ad26.COV2.S: low dose—5 × 1010 vp, high dose—1 × 1011 vp; (A) Prime-Boost (low), (B) Prime-Boost (high), (C) Prime-Placebo (low), (D) Prime-Placebo (high), (E) ≥ 65yo, Prime (high), (F) ≥ 65yo, Prime (low); stabilized pre-fusion spike protein; expressed as EU (GMC, 95% CI); (7A, B) Folegatti, ChAdOx SARS-CoV-2: unspecified dose—5 × 1010 vp; (A) Prime only, (B) Prime-Boost; trimeric spike protein; expressed as EU (IQR); (8A–F) Ramasamy, ChAdOx: low dose—2.2 × 1010 vp, unspecified dose— 3.5–6.5 × 1010 vp; (A) Prime-Boost, 18–55 y/o (low), (B) Prime-Boost, 56–69 y/o (low), (C) Prime-Boost, ≥70 y/o (low), (D) Prime-Boost, 18–55 y/o (unspecified), (E) Prime-Boost, 56–69 y/o (unspecified), (F) Prime-Boost, ≥70 y/o (unspecified); Spike protein; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (9A-F) Jackson,mRNA-1273: low dose—25 µg, intermediate dose—100 µg, high dose—250 µg; (A) Prime-Boost (low) S2-P, (B) Prime-Boost (intermediate) S2-P, (C) Prime-Boost (high) S2-P, (D) Prime-Boost (low) RBD, (E) Prime-Boost (intermediate) RBD, (F) Prime-Boost (High) RBD; Expressed as GMT (95% CI); (10A-E) Anderson, mRNA-1273: low dose—25 µg, high dose—100 µg; A) Boost, 56–70 y/o (low), (B) Boost, ≥70 y/o (low), (C) Boost, 18–55 y/o (high), (D) Boost, 56–70 y/o (high), (E) Boost, ≥70 y/o (high); S-2P; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (11A-F) Walsh, BNT162b2: low dose—10 µg, intermediate dose—20 µg, high dose—30 µg; (A) Boost, 18–55 y/o (low), (B) Boost, 65–85 y/o (low), (C) Boost, 18–55 y/o (intermediate), (D) Boost, 65–85 y/o (intermediate), (E) Boost, 18–55 y/o (high), (F) Boost, 65–85 y/o (high); S1; expressed as GMT; (12A-F) Walsh, BNT162b1: low dose—10 µg, intermediate dose—20 µg, high dose—30 µg; (A) Boost, 18–55 y/o (low), B) Boost, 65–85 y/o (low), (C) Boost, 18–55 y/o (intermediate), (D) Boost, 65–85 y/o (intermediate), (E) Boost, 18–55 y/o (high), (F) Boost, 65–85 y/o (High); S1; expressed as GMT; (13A-C) Mulligan, BNT162b1: (A) Prime-Boost (10 µg dose), (B) Prime-Boost (30 µg dose), (C) Prime-Boost (100 µg dose); RBD; expressed as GMT; (14A-E) Sahin, BNT162b1: (A) Prime-Boost (1 µg dose), (B) Prime-Boost (10 µg dose), (C) Prime-Boost (30 µg), (D) Prime-Boost (50 µg), (E) Prime (60 µg); RBD; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (15A, B) Che, inactivated: intermediate dose—100 EU, high dose—150 EU; Spike protein; expressed as GMET (95% CI); (16A) Xia, inactivated Phase 1: low dose—2.5 µg, intermediate dose—5 µg, high dose—10 µg, 3rd boost of Prime-Boost; inactivated SARS-CoV-2; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (16B) Xia, inactivated Phase 2: intermediate dose—5 µg 3rd Boost of Prime-Boost; inactivated SARS-CoV-2; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (17A, B) Zhang, CoronaVac, Phase 1: (A) Prime-Boost (low dose—3 µg), (B) Prime-Boost (high dose—6 µg); RBD; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (17C) Zhang, CoronaVac, Phase 2: low dose—3 µg, high dose—6 µg, 2nd boost in a Prime-Boost; RBD; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (18A–C) Ella, BBV152 Phase 1: low dose—3 µg, high dose—6 µg; (A) post prime (low + Algel-IMDG), (B) Post prime (high + Algel-IMDG), (C) post prime (high + Algel); RBD; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (19A, B) Ella, BBV152 Phase 2: (A) Prime-Boost (low dose 3 µg + Algel-IMDG), (B) Prime-Boost (high dose 6 µg + Algel-IMDG); RBD; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (20A–D) Keech, NVX-CoV2373: low dose—5 µg, high dose—25 µg; (A) Prime-Boost (high), (B) Prime-Boost (Low + adjuvant), (C) Prime-Boost (high + adjuvant), (D) Prime-Boost (high + placebo); Spike protein; expressed as EU (GMT, 95% CI); (21A, B) Tebas, INO-4800: low dose—1.0 mg, high dose—2.0 mg; Boost in a Prime-Boost; (A) low dose, (B) high dose; Spike Protein (S1/2); expressed as reciprocal binding titre (median, IQR); (22A–E) Richmond, SCB-2019: low dose—3 µg, intermediate dose—9 µg, high dose—30 µg; (A) Boost, 18–54 y/o (low, intermediate, high, non-adjuvanted). (B) Boost, 18–54 y/o (low, intermediate, high + CpG/Alum), (C) Boost, 18–54 y/o (low, intermediate, high + AS03), (D) Boost, 55–75 y/o (low, intermediate, high, CpG/Alum), (E) Boost, 55–75 y/o (low, intermediate, high + AS03); SCB-2019 binding antibody; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (23A) Folegatti, ChAdOx-MERS-CoV: low dose—5 × 109 vp, intermediate dose—2.5 × 1010 vp, high dose—5 × 1010 vp; Spike; expressed as EU (95% CI); (24A–C) Modjarrad, GLS-500-MERS-CoV: low dose—0.67 mg, intermediate dose—2 mg, high dose—6 mg, (A) Prime-Boost (low), (B) Prime-Boost (intermediate), (C) Prime-Boost (high); Spike protein; expressed as GMET (95% CI).

The vaccine achieving the highest Ab titer was the Jackson, Anderson mRNA-1273-SARS-CoV-224,25 vaccine. It exhibited dose and boosting dependent increases in Ab titer. The high-dose Keech NVX-CoV237339 vaccine elicited similar Ab titers to the unboosted mRNA-1273-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. The next highest antibody binding titers were seen in the Sahin, Walsh BNT162b1-SARS-CoV-228,30 and Logunov16, rAd26/rAd5-SARS-COV-2 followed by Ella, BBV15236,37, Sadoff, Ad2618 and Folegatti/Ramasamy, SARS-CoV-2 ChAdOx19,20. Several vaccines display boost-dependant increases in Ab titer including Logunov AdH26-SARS-CoV-216; Ramasamy, Folegatti ChAdOx-SARS-CoV-219,20; and Sahin, Walsh BNT162b1-SARS-CoV-228,30. Modjarrad DNA-MERS-CoV45 elicited similar Ab responses to the Zhu, AdH-5-SARS-CoV-214,15 and Folegatti, ChAdOx-MERS-CoV23 vaccines, and exhibited dose-dependent increase in responses in the middle and high dose vaccine group. The inactivated virus vaccines included in this review achieved similar Ab responses with minimal boost or dose-dependent increases in titers32,38,44.

Comparing human and NHP GMT ELISA-IgG responses, human studies reported mean Ab titers similar to ELISA-IgG responses seen in NHP studies (Supplementary Fig. 3A).

Next we looked at human vaccine trial data for nAb responses (Fig. 6). The adjuvanted Keech, NVX-CoV2373-SARS-CoV-239 and Chu, mRNA-127326 Prime-Boost vaccine groups achieved the highest nAb responses followed by the Sadoff, Ad26-SARS-CoV218 vaccine then Folegatti/Ramasamy, SARS-CoV-2 ChAdOx19,20 and Sahin, Walsh BNT162b1-SARS-CoV-228,30. Both are dependent on the boost to achieve high nAb titers. At the vaccination dose of 30 µg, the 56–85 yo cohort of the Walsh, BNT162B1/228 study achieved lower nAb titers than the 15–55 yo cohorts. A similar reduction in nAb titers was seen with increasing age across the cohorts (18–55 yo, 56–70 yo and >70 yo) in Ramasamy, SARS-CoV-2 ChAdOx20. This emphasizes the importance of the boosting dose to achieve optimal nAb titers particularly in older age groups. The importance of a boost dose to achieve optimal nAb titers is also seen in the Jackson/Anderson mRNA-127324,25 and Folegatti, SARS-CoV-2 ChAdOx19 studies using a pseudotyped virus nAb assay (Fig. 7). Data from the >70 yo age group in the Anderson, mRNA-1273 study25 (Fig. 7) is noteworthy as boosting is needed to achieve a measurable titer. In Chu, mRNA-127326 there was no reduction in nAb response with increasing age.

Blue = low; black = intermediate; red = high dose of vaccine indicated. Neutralizing antibody titre recorded circa 28 days post injection. Log transformed scale used. Vp viral particles, GMT geometric mean titre, CI confidence interval, PFU, plaque-forming units, GMET geometric mean endpoint titre, IQR interquartile range, CCID cell culture infectious dose, TCID tissue culture infectious dose, IC inhibitory concentration, SU SARS-CoV-1 units. (1A) Zhu, AdH-5, Phase 1: low dose—5 × 1010 vp, intermediate dose—1 × 1011 vp, high dose: 1.5 × 1011 vp; live SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (2A) Zhu, AdH-5, Phase 2: low dose—1 × 1011 vp, high dose—5 × 1010 vp; live SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (3A) Logunov, rAdH26/rAd5-Lyo: lyophilised formulation. Unspecified dose—1011 vp; Prime-Boost; microneutralization assay, 100TCID50, expressed as GMT (95% CI); (3B) Logunov, rAdH26/rAd5-Vac: frozen formulation. Unspecified dose—1011 vp; Prime-Boost; microneutralization assay, 100TCID50, expressed as GMT (95% CI); (4A) Logunov, rAdH26/rAd5-Vac Phase 3 trial: unspecified dose—1011 vp. Post boost in a Prime-Boost; microneutralization assay TCID50; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (5A–F) Sadoff, Ad26: low dose—5 × 1010 vp, high dose—1 × 1011 vp; (A) Prime-Boost (low), (B) Prime-Boost (high), (C) Prime-Placebo (low), (D) Prime-Placebo (high), (E) ≥ 65yo, Prime (high), (F) ≥ 65yo, Prime (low); live SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay (IC50); expressed as GMT (95% CI); (6A, B) Folegatti, ChAdOx SARS-CoV-2: unspecified dose—5 × 1010 vp; (A) Prime only, (B) Prime-Boost; microneutralization assay (MNA50); expressed as GMT (IQR); (7A–F) Ramasamy, ChAdOx: low dose—2.2 × 1010 vp, unspecified dose—3.5–6.5 × 1010 vp; (A) Prime-Boost, 18–55 y/o (low), (B) Prime-Boost, 56–69 y/o (low), (C) Prime-Boost, ≥70 y/o (low), (D) Prime-Boost, 18–55 y/o (unspecified), (E) Prime-Boost, 56–69 y/o (unspecified), (F) Prime-Boost, ≥70 y/o (unspecified); microneutralization assay (MNA80; normalised IC50 values); (8A–H) Chu, mRNA-1273: low dose—50 µg, high dose—100 µg. (A) Prime-Boost, 18–55 y/o (low), (B) Prime-Boost, 18–55 y/o (high), (C) Prime-Boost, 55–65 y/o (low), (D) Prime-Boost, 55–65 y/o (high), (E) Prime-Boost, 65–75 y/o (low), (F) Prime-Boost, 65–75 y/o (high), (G) Prime-Boost, ≥75 y/o (low), (H) Prime-Boost, ≥75 y/o (High); live virus microneutralization assay (MN50). Expressed as GMT (95% CI); (9A–F) Walsh, BNT162b1: low dose—10 µg, intermediate dose—20 µg, high dose—30 µg; (A) Boost, 18–55 y/o (low), (B) Boost, 65–85 y/o (low), (C) Boost, 18–55 y/o (intermediate), (D) Boost, 65–85 y/o (intermediate), (E) Boost, 18–55 y/o (high), (F) Boost, 65–85 y/o (high); fluorescent-based neutralization assay, 50% neutralization titres expressed as GMT (95% CI); (10A–F) Walsh, BNT162b2: low dose—10 µg, intermediate dose—20 µg, high dose—30 µg; (A) Boost, 18–55 y/o (low), (B) Boost, 65–85 y/o (low), (C) Boost, 18–55 y/o (intermediate), (D) Boost, 65–85 y/o (intermediate), (E) Boost, 18–55 y/o (high), (F) Boost, 65–85 y/o (high); fluorescent-based neutralization assay, 50% neutralization titres expressed as GMT (95% CI); (11A–C) Mulligan, BNT162b1: (A) Prime-Boost (10 µg dose), (B) Prime-Boost (30 µg dose), (C) Prime (100 µg dose); fluorescent-based neutralization assay, 50% neutralization titres expressed as GMT, (95% CI); (12A–E) Sahin, BNT162b1: (A) Prime-Boost (1 µg dose), (B) Prime-Boost (10 µg dose), (C) Prime-Boost (30 µg), (D) Prime-Boost (50 µg), (E) Prime (60 µg); fluorescent-based neutralization assay, 50% neutralization titres expressed as GMT, VNT50 (95% CI); (13A, B) Che, inactivated: intermediate dose—100 EU, high dose—150 EU; live SARS-CoV-2 neutralisation assay (CCID50); expressed as GMT (95% CI); (14A) Xia, BBIBP-CorV: low dose—2 µg, intermediate dose—4 µg, high dose— 8 µg, Prime-Boost; live SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (15A-B) Zhang, CoronaVac, Phase 1: (A) Prime-Boost (low dose—3 µg), (B) Prime-Boost (high dose—6 µg); live SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (15C) Zhang, CoronaVac, Phase 2: low dose—3 µg, high dose—6 µg; 2nd boost in a Prime-Boost; live SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (16A, B) Wu, CoronaVac: Phase 1: intermediate dose—3 µg, high dose—6 µg; (A) Prime-Boost, ≥60 y/o (intermediate), (B) Prime-Boost, ≥60 y/o (high); live SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (16C–E) Wu, CoronaVac: Phase 2: low dose—1.5 µg, intermediate dose—3 µg, high dose—6 µg; (C) Boost, ≥60 y/o (low), (C) Boost, ≥60 y/o (intermediate), (C) Boost, ≥60 y/o (high); live SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (17A–C) Ella, BBV152 Phase 1: low dose—3 µg, high dose—6 µg; (A) post prime (low + Algel-IMDG), (B) post prime (high + Algel-IMDG), (C) post prime (high + Algel); microneutralization assay (MNT50). Expressed as GMT (95% CI); (18A, B) Ella, BBV152 Phase 2: (A) Prime-Boost (low dose 3 µg + Algel-IMDG), (B) Prime-Boost (high dose 6 µg + Algel-IMDG); microneutralization assay (MNT50). Expressed as GMT (95% CI); (19A–D) Keech, NVX-CoV2373: low dose—5 µg, high dose—25 µg; (A) Prime-Boost (5 µg +adjuvant), (B) Prime-Boost (25 µg no adjuvant), (C) Prime-Boost (25 µg + adjuvant), (D) Prime-Boost (25 µg + Placebo); microneutralization assay (IC99); expressed as GMT (95% CI); (20A) Richmond, SCB-2019: low dose—3 µg, intermediate dose—9 µg, high dose—30 µg; (A) Boost, 18–54 y/o (low, intermediate, high, AS03). (B) Boost, 55–75 y/o (low, intermediate, high + AS03), (C) Boost, 18–54 y/o (Low, intermediate, High + CpG/Alum), (D) Boost, 55–75 y/o (low, intermediate, High, CpG/Alum). (E) Boost, 18–54 y/o (high non-adjuvanted); SCB-2019 binding antibody. Expressed as GMT (95% CI); (21A) Koch, MVA-MERS-CoV: low dose—1 × 107 PFU, high dose—1 × 108 PFU Boost in a Prime-Boost; live MERS-CoV neutralization assay; expressed as the GMT (95% CI); (22A) Lin, Inactivated-SARS-CoV-1: low dose—16 SU, high dose—32 SU; live virus neutralization assay (CCID50); expressed as GMT (95% CI); (23A) Modjarrad, GLS-500-MERS-CoV: low dose—0.67 mg, intermediate dose—2 mg, high dose—6 mg; 2nd Boost in a Prime-Boost; live MERS-CoV neutralization assay (TCID50); expressed as GMET (95% CI); (24A) Folegatti, ChAdOx-MERS-CoV: low dose—5 × 109 vp, intermediate dose—2.5 × 1010 vp, high dose—5 × 1010 vp; live MERS-CoV neutralization assay (TCID50); expressed as GMT (95% CI).

Blue = low; black = intermediate; red = high dose of vaccine indicated. Neutralizing antibody titre recorded circa 28 days post injection. Log transformed scale used. Vp Viral particles, GMT geometric mean titre, CI confidence interval, PFU plaque-forming units, GMET geometric mean endpoint titre, IQR interquartile range, CCID cell culture infectious dose, TCID tissue culture infectious dose, IC inhibitory concentration, SU SARS-CoV-1 units, ID infectious dose, IC inhibitory concentration. (1A) Zhu, AdH-5 Phase 1: low dose—5 × 1010 vp, intermediate dose—1 × 1011 vp, high dose—1.5 × 1011 vp; VSV pseudovirus system expressing spike protein; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (2A) Zhu, AdH-5 Phase 2: low dose—1 × 1011 vp, high dose—5 × 1010 vp; VSV pseudovirus system expressing spike protein; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (3A, B) Folegatti, ChAdOx SARS-CoV-2: unspecified dose—5 × 1010 vp; (A) Prime, (B) Prime-Boost; lentivirus pseudovirus system (IC50) expressed as median titre (IQR); (4A–D) Voysey, ChAdOx: unspecified dose—5 × 1010vp; (A) Prime-Boost, <6 week interval, (B) Prime-Boost, 5–8 week interval, (C) Prime-Boost, 9–11 week interval, (D) Prime-Boost, ≥12 week interval; lentivirus pseudovirus system (IC50) expressed as GMT (95% CI); (5A–C) Jackson, mRNA-1273: low dose—25 µg, intermediate dose—100 µg, high dose—250 µg; (A) Prime-Boost (low), (B) Prime-Boost (intermediate), (C) Prime-Boost (high); lentivirus pseudovirus system expressing spike protein (ID50); expressed as GMT (95% CI); (6A–E) Anderson, mRNA-1273: low dose—25 µg, high dose—100 µg; (A) Boost, 56–70 y/o (low), (B) Boost, ≥70 y/o (low), (C) Prime-Boost, 18–55 y/o (high), (D) Boost, 56–70 y/o (high), (E) Prime-Boost, ≥70 y/o (high); lentivirus pseudovirus system expressing spike protein (ID50); expressed as GMT (95% CI); (7A, B) Zhang, CoronaVac, Phase 1: low dose—3 µg, high dose—6 µg; (A) Prime-Boost (low), (B) Prime-Boost (high); pseudovirus neutralisation assay; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (7C) Zhang, CoronaVac, Phase 2: low dose—3 µg, high dose—6 µg, 2nd boost in a Prime-Boost; pseudovirus neutralisation assay; expressed as GMT (95% CI); (8A) Folegatti, ChAdOx-MERS-CoV: low dose—5 × 109 vp, intermediate dose—2.5 × 1010 vp, high dose—5 × 1010 vp; lentivirus pseudovirus system expressing spike protein (IC50); expressed as GMT (95% CI).

Studies looking at human and NHP live and pseudovirus nAb responses to vaccination report responses of a similar order of magnitude (Supplementary Fig. 3B, C).

A number of vaccines display convergence between ELISA, pseudotype virus neutralization and live virus nAb titers. In the Anderson mRNA-1273-SARS-CoV vaccine groups25 there were significant dose-dependent increases in pseudotype virus nAb titer, similar to the ELISA-IgG responses (Figs. 5, 6, and 7). A similar relationship exists between the live nAb and ELISA-IgG responses in the Sahin, BNT162b130, Logunov, AdH26/5-Vac/Lyo16 and Ramasamy, ChAdOx SARS-CoV-220 vaccines.

Studies have reported pre-existing Ab against the vaccine viral vector itself. Supplementary Table 12 details pre-existing titers: the Zhu, AdH-5-SARS-CoV-214,15 vectored vaccines showed high levels of pre-existing nAb with an average of 52.2% (range: 44–58%) of participants having pre-existing nAb (>1:200, titer) to the AdH-5 virus vector. Pre-existing Ab roughly halved the Ab response to the vaccine. About 9.2% (range: 5–13%) of participants in the Logunov, AdH26/5-Vac/Lyo16 trial had pre-existing anti-vector nAb. However, no significant correlation was found between titers of anti-vector nAb and titers of RBD specific IgG. Only one percent of participants in the Folegatti, ChAdOx-SARS-CoV-219 had pre-existing anti-vector nAb of >1:200 although 19% did have nAb. In the larger Ramasamy, ChAdOx-SARS-CoV-2 trial20, there were no pre-existing nAbs, however the anti-ChAdOx nAb titer increased following prime vaccination, but did not after boost vaccination (Supplementary Table 12).

T cell responses

T cell responses were evaluated using T cell ELISpot IFNγ responses and/or ICS. Ten human studies evaluated T cell ELISpot IFNγ responses (Fig. 8). The highest IFNγ ELISpot responses were seen in the Folegatti23, ChAdOx-MERS-CoV and the Ramasamy20, ChAdOx-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine studies. The Zhang34, CoronaVac-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine study showed somewhat lower IFNγ SFC. Limited analysis of mean IFNγ ELISpot responses of other trials demonstrated dose-dependent increases in responses in all groups of the Modjarrad, DNA-MERS-CoV45 and Koch, MVA-MERS-CoV42 vaccines. Overall the log-transformed mean IFNγ ELISpot cell response in the human studies was 2.3 with a range of 2.3. Similar responses were obtained in NHP studies (Supplementary Fig. 3D). As had been seen for the nAb response, the IFNγ ELISpot response to a single 60 µg dose of the Sahin BNT162b130 vaccine was below the lower limit of detection in the majority of vaccinees at d 29.

Blue = low; black = intermediate; red = high dose of vaccine indicated. IFNγ ELISpot data recorded circa 28 days post injection. Log transformed scale used. Vp viral particles, GMT geometric mean, CI confidence interval, IQR interquartile range. (1A) Zhu, AdH-5 Phase 1: low dose—5 × 1010 vp, intermediate dose—1 × 1011 vp, high dose—1.5 × 1011 vp; expressed as IFNy expressing cells/106 PBMC (95% CI); (2A) Zhu, AdH-5 Phase 2: low dose—1 × 1011 vp, high dose—5 × 1010 vp; expressed as IFNy expressing cells/106 PBMC (95% CI); (3A, B) Folegatti, ChAdOx SARS-CoV-2: unspecified dose—5 × 1010 vp; (A) Prime only, (B) Prime-Boost; expressed as SFC/106 PBMC (95% CI); (4A–E) Ramasamy, ChAdOx: low dose—2.2 × 1010 vp, unspecified dose—3.5–6.5 × 1010 vp; (A) Prime-Boost, 56–69 y/o (low), (B) Prime-Boost, ≥70 y/o (low), (C) Prime-Boost, 18–55 y/o (unspecified), (D) Prime-Boost, 56–69 y/o (unspecified), (E) Prime-Boost, ≥70 y/o (unspecified); expressed as SFC/106 PBMC (IQR); (5A, B) Zhang, CoronaVac, Phase 1: low dose—3 µg, high dose—6 µg; (A) post boost (low), (B) post boost (high); expressed as SFC/106 PBMC (95% CI); (6A–C) Ella, BBV152 Phase 1: low dose—3 µg, high dose—6 µg; (A) post prime (low + Algel-IMDG), (B) post prime (high + Algel-IMDG), (C) post prime (high + Algel); expressed as SFC/106 PBMC (IQR); (7A, B) Tebas, INO-4800: low dose—1.0 mg, high dose—2.0 mg; Boost in a Prime-Boost; (A) low dose, (B) high dose; expressed as IFNy expressing cells/106 PBMC (median, IQR); (8A, B) Koch, MVA-MERS-CoV: (A) low dos—1 × 107 PFU, (B) high dose—1 × 108 PFU; Expressed as SFC/106 PBMC (95% CI); (9A) Martin, DNA-SARS-CoV-1: unspecified dose—4 mg; Prime-Boost-Boost; expressed as SFC/106 PBMC; (10A) Modjarrad, GLS-500-MERS-CoV: low dose—0.67 mg; Prime-Boost-Boost; expressed as SFC/106 PBMC (95% CI); (11A) Modjarrad, GLS-500-MERS-CoV: intermediate dose— 2 mg; Prime-Boost-Boost; expressed as SFC/106 PBMC (95% CI); (12A) Modjarrad, GLS-500-MERS-CoV: high dose—6 mg; Prime-Boost-Boost; expressed as SFC/106 PBMC (95% CI); (13A) Folegatti, ChAdOx-MERS-CoV: low dose—5 × 109 vp, intermediate dose—2.5 × 1010 vp, high dose—5 × 1010 vp; expressed as SFC/106 PBMC (95% CI).

ICS used to characterize T cell cytokine responses and subsets was described in 14 human studies (Supplementary Table 13). While it is hard to compare effector cell frequencies directly between ELISpot and ICS platforms (since the latter encompass diverse strategies for co-stimulation, peptide panels, gating and cytokine readouts), it can nevertheless be seen that very high responder frequencies are achieved, often around 0.2% of gated CD4+ cells being cytokine-positive on stimulation; see for example Jackson mRNA-1273-SARS-CoV-224 intermediate dose, or the Keech NVX-CoV237339 Phase 2 trial data. Cytokine-positive CD4+ T cell responses were more prominent than CD8+ T cell responses in most studies and IFNγ+ expression was the most common T cell effector function recorded in human studies. There was little evidence for Th2 cytokine profiles with Th1 bias most prevalent, although some subjects in Keech, NVX-CoV237339 make a detectable IL-5/IL-13 response.

Five NHP studies evaluated T cell subset responses by ICS. CD4+ and CD8+ subset responses were stimulated in all studies (Supplementary Table 13). CD8+ T cells were the most prominent subset stimulated in NHP trials, in contrast to the findings in human studies. The Yu, DNA-SARS-CoV-254 vaccine elicited minimal CD4/8+ IL-4 responses relative to the CD8/4+IFNγ responses, indicative of a Th1/Tc1 bias; other NHP studies also recorded Th1/Tc1 responses following vaccination46,48. As in the human data, IFNγ+ effector function was most prominent in NHP studies (Supplementary Table 13). No significant Th2 responses were recorded following vaccination in any NHP study. The Muthumani, DNA-MERS-CoV56 and Corbett, mRNA-1273-SARS-CoV48 NHP vaccine groups exhibited dose-dependent increase in T cell cytokine responses.

Efficacy

Five SARS-CoV-2 human Phase 3 trials reported vaccine efficacy17,21,22,27,31 (Supplementary Table 7). Polack, BNT162b231, Baden, mRNA-127327 and Logunov, rAd26r/Ad517 achieved remarkably high efficacy, 94.6%, 94.1% and 91.6%, respectively. Using pooled data from the UK and Brazil Voysey, ChAdOx21 reported an efficacy of 70.4%. Follow-up analysis of pooled data from the UK, South Africa and Brazil, Voysey, ChAdOx22 reported an efficacy of 66.7% (Supplementary Table 7).

Of 23 NHP studies (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5), 15 evaluate vaccine efficacy. Eleven evaluated viral load by RT-PCR and six measured nAb post-challenge; challenge doses varied greatly. All studies reported a reduction in peak viral load (Log10) compared to control groups. Peak viral load was significantly higher in control groups compared to vaccinated groups post-challenge. Each reported significant protection including, where indicated, from lung pathology/pneumonia, though none attain sterilizing immunity except for the Gao PiCoVacc50 inactivated whole virus vaccine given as weekly doses for 3-weeks and in the Guebre-Xabier NVX-CoV2373 vaccine51. A caveat of NHP challenge studies is the short time interval between immunization and challenge, 1–6 weeks being most common.

Discussion

The benefits of comparative evaluation of datasets within the context of a systematic review and meta-analysis are self-evident at a time when enthusiasm for news of vaccine ‘breakthroughs’ can lead to incomplete reports in absence of opportunity for careful, granular, data-led comparison. We considered datasets with respect to binding and neutralizing Ab, prior anti-vector Ab, T cell responses and protection up to March 22, 2021. In doing so, it is a given that the correlates of protection (CoP) for COVID-19—which immune parameter/value gives the clearest actual indicator of protection—are not agreed, though evidence is accruing for nAb titer as a key CoP46,54,69.

Safety evaluation has encompassed a range of potential concerns, from initial reactogenicity profile to downstream post-challenge ADE or type 2 lung pathology. The meta-analysis shows a relatively low incidence of local and systemic AE at immunization. It is premature to comment on ADE in SARS-CoV-2 trials and rollout, but thus far it appears not to be an issue. The hypothetical concern originates in macaque studies evaluating either an MVA-vectored vaccine expressing SARS-CoV-1 spike or a SARS-CoV inactivated vaccine, both which resulted in ADE-associated lung immunopathology70. An additional mechanism of vaccine-dependent, post-challenge immunopathology is Th2-dependent eosinophilic lung infiltration. Th2 cytokine-dependent lung immunopathology following virus challenge has been noted in vaccines for SARS-CoV-1 and for MERS-CoV in mice, ferrets and NHP71. Again, such effects would only become apparent on subsequent exposure to virus, but it is encouraging that T cell responses across all the vaccine platforms compared here show strong skewing to Th1 cytokines, and little Th2 polarization. While anaphylaxis has been a very rare SAE in rollout of the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine, this was likely not picked up in the smaller sample size of the Phase 3 trial and with any vaccine allergic individuals excluded72,73. European rollout has highlighted rare development of thrombotic thrombocytopenia following ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and Ad26.COV2.S vaccination74,75,76; this was not a feature identified in Phase III trials.

This review has considered several inactivated virus vaccines, favored for the long track record of the approach (including polio vaccination) and diversity of viral antigens presented, though often considered to elicit less durable immunity. The Lin et al inactivated SAR-CoV1 vaccine elicited high nAb titers with a favourable safety profile, while the similar approach used for inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 also leads to a vaccine which is immunogenic and protective in NHP short-term challenge44,49.

Among the many adenoviral-vector based approaches are the ChAdOx, AdH-5 and AdH26/5 vectored vaccines. ChAdOx vectored vaccines have been clinically tested over several years and across diverse infections77,78,79, so that there is a very expansive dataset on the ability to elicit robust Ab and, especially, strong T cell responses, including in the elderly and immunosuppressed. The choice of the chimpanzee viral vector to a considerable degree mitigates the confounder of prior Ab to limit the vaccine. Frequencies of virus-specific T cells induced by the ChAdOx vectors appear in most cases considerably higher than mean T cell responses induced by natural infection, though the extent to which this is a direct CoP remains to be seen. Of others considered here, the MVA-MERS-CoV vector vaccine42 produced low levels of nAb compared to other candidates. The mRNA-1273-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine elicited the highest Ab responses of any vaccine after a single dose, with a significant increase upon boosting24,25. Th1 cytokine responses were also strong, though requiring a boost. The Folegatti, ChAdOX-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine elicited strong Ab and T cell responses after a single injection, increasing further after boost19. At present, there is no data to suggest that Th2 immunopathology will be a significant risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. However, ongoing scrutiny will be needed to exclude the possible risk of Th2 immunopathology.

The finding that some vaccines require a second boost for optimal responses while others may not is an important factor for decision-making. The global roll-out of effective vaccines demands unprecedented logistics to achieve coverage for a first round, and all the harder for a second round. At the time of writing, Phase 3 trial data are awaited from the Janssen Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19, which encompasses a 1-dose protocol.

Prior immune memory has been a significant hurdle limiting the immunogenicity of adenoviral and other virus-vectored vaccines80. Substantial pre-existing nAb responses were identified to the Zhu, AdH-5-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine14,15. Approximately 50% of those vaccinated were positive for pre-existing nAb >1:200, associated with a lower response to vaccination. Pre-immunity has implications for the geographic utility of vaccines, as certain regions have higher rates of specific disease which cause pre-immunity81.

Rhesus macaques develop pneumonia and other clinical aspects of SARS-CoV-2 like disease82,83 as well as Ab and T cell responses similar to that seen in humans. Each of the tested candidates showed promising efficacy in NHP challenge, with caveats that these studies use greatly differing challenge doses making direct comparison difficult, and also that there tends to be a very short interval between priming and challenge. NHP studies, along with human challenge studies, will continue to play a key role for vital points that are hard to deduce from other approaches: ability of vaccines to achieve sterilizing immunity and delineation of CoP84.

It was difficult to attain across the board comparison of T cell immunity due to the different assays reported. Similarly, a lack of standardised antibody binding and neutralizing antibody testing means cross-comparison of binding antibody and nAb titers is limited by inter-assay variability. Efforts by the World Health Organisation to develop an international standard for SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay calibration may go some way towards resolving this issue85. Across vaccine platforms there are trade-offs between Ab titer, T cell frequency, reactogenicity and efficacy, with no single platform uniformly outstanding. RNA-based approaches have proved highly successful, though they can show a disadvantageous AE profile at higher doses and require a boost for maximal efficacy. The adenovirus-based approaches, especially ChAdOx-SARS-CoV-2, are of interest for their ability to induce exceptionally high T cell responses, probably higher than from natural infection, though this may prove less decisive if it transpires that nAb titer is of overriding significance as a CoP. NVX-CoV2373 strategy for spike protein with adjuvant bodes well for a simple approach to attaining exceptionally high, effective high nAb titers and strong protection in NHP challenge studies39,51.

There were limitations inherent in this study: while new SARS-CoV-2 vaccine data is being produced rapidly, we have had to impose a finite search window, excluding some candidates that have received attention from press releases and preprints. Gaps in reporting of precise data in some studies prevented the completion of an effective meta-regression analysis of study metrics and determinants of vaccine safety, immunogenicity and efficacy. The lack of control groups in some human trials resulted in a limited meta-analysis of AE.

At a time when we have already witnessed the successful development and roll-out of several COVID-19 vaccines, this review of 23 NHP and 32 human studies offers a template for high-granularity appraisal of the detailed metrics. To fully match the immune studies to fine-tuning of efficacy will require a better understanding of the CoP, particularly, relative importance of nAb and CD4 + responses. However, the front-running vaccines show excellent induction of nAb and T cell responses, and the associated ability to substantially limit severe disease, hospitalisation and death.

Vaccine efficacy against emerging variant strains may, however, be diminished necessitating that vaccines be adapted to act specifically against variant strains and rapidly rolled out. There may also be opportunities to develop heterologous prime boost immunization schedules across vaccine platforms, potentially offering better immune responses and protection. The emergence of variant strains makes rapid mass rollout of high efficacy vaccines essential to reduce any selective advantage. Furthermore, as contingency plans develop, addressing the possible requirement for periodic boosters priming immunity targeted to variant sequences, it will be ever more important to have facilitated protocols that can intersperse use of different platforms, minimizing potential for limitation by anti-vector immunity.

Methods

Search strategy & eligibility criteria

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in line with PRISMA guidelines86. An electronic search of PubMed and EMBASE databases was carried out using search terms and phrases related to HCoV vaccine candidates (Supplementary Table S1). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined to ensure all relevant studies were identified (Supplementary Table S2). Studies or trials evaluating the safety, immunogenicity or efficacy of a coronavirus vaccine candidate in humans or NHP were included. The need to impose a defined search period and also to exclude non-peer-reviewed preprints means that there are a large number of known vaccine candidates in Phase I/II or III trials that have been widely discussed in the press, but are not included in this review. The data included is updated to March 22, 2021 This study is registered with PROSPERO: CRD4202019030.

Study selection & data extraction

Study selection was performed following pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria as described (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2) extracting vaccine characteristics: platform, insert, route of administration, doses and schedule. Characteristics of challenge in NHP studies were also recorded: challenge virus, dose and swab location. For clarity in the Results and Discussion, we discuss specific, named studies by referring to the first author of the study and the shorthand name for the tested vaccine (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 5). Data on local and systemic AE for each of the studies were obtained.

Geometric mean titer (GMT) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; IgG, IgG subtypes or IgA) and neutralization assays were extracted. Mean spot-forming cells per million peripheral blood mononuclear cells (SFC/million PBMC) were extracted for T cell ELISpots. If numerical Ab or T cell response datasets were not available, estimates were derived from respective graphs. Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) data was obtained to analyze T cell responses, where described. Regarding vaccine efficacy analysis from NHP studies, challenge dose, viral strain, peak viral load, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) swab location, RT-PCR positivity data and neutralizing Ab titers post-challenge were collated. To analyze human vaccine efficacy, the efficacy endpoints and overall vaccine efficacy (%) were extracted from relevant studies.

Data analysis

RevMan 5.2 and GraphPad Prism were used for statistical analysis. With respect to AE analysis, Forest plot analysis was used to look at interstudy heterogeneity for AEs. Results were reported as risk ratios (RR) comparing the incidence of an AEs in experimental groups to control groups. A random effects, Mantel–Hanzeal model (95% CI) was used to determine effect sizes between studies. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using I2 statistics: an I2 value of >50%; P < 0.05 was considered to represent severe heterogeneity, I2 value of 30–50%; P < 0.05 was considered to represent moderate heterogeneity and <30%; P < 0.05 was deemed to constitute insignificant heterogeneity. Since many first-in-human studies lacked control groups, descriptive analysis of AE was conducted. A grade three AE is here considered a severe AE. Serious AE (Grade 4) recorded in human studies were presented in tabular form.

Due to the existence of multiple vaccine groups in each study, all vaccine groups were considered a statistical unit87. Vaccine groups are considered to be experimental and control groups in the human and NHP trials. If a single dose of a vaccine candidate was used, it is defined as an unspecified dose.

To evaluate interstudy Ab responses, we analyzed the GMT and nAb titer from ELISA and neutralizing assays respectively. There was a lack of comprehensive numerical datasets of Ab titers across human studies; in some cases Ab titers were estimated from graphical representations. Ab titers analyzed were collected circa 28 d after a given injection, allowing for inclusion of Ab titer data from vaccine regimens involving prime/boosts. Transformed mean log Ab titers (Log10) were estimated from human and NHP studies to determine statistical difference between groups using an unpaired t test (95% CI).

T cell responses were evaluated by extracting IFNγ ELISpot data. In some cases, estimated frequencies were extracted from graphs. T cell responses were extracted circa 28 d after individual immunizations and represented by Forest plot to show interstudy differences in ELISpot SFC/million PBMC. Transformed log mean T cell responses were obtained from human and NHP studies to test statistical differences between NHP and human groups.

For NHP efficacy analysis, we analyzed differences between control and experimental peak viral loads and nAb responses (Log10) post-challenge to examine vaccine-induced protection.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article (and Supplementary Information files).

Code availability

This study did not use custom code.

References

De Wit, E., Van Doremalen, N., Falzarano, D. & Munster, V. J. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 14, 523–534 (2016).

Memish, Z. A., Perlman, S., Van Kerkhove, M. D. & Zumla, A. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet 395, 1063–1077 (2020).

WHO. Mers Situation Update January 2020. http://applications.emro.who.int/docs/EMRPUB-CSR-241-2019-EN.pdf (WHO, 2020).

Roper, R. L. & Rehm, K. E. SARS vaccines: where are we? Expert Rev. Vaccines. 8, 887–898 (2009).

Mubarak, A., Alturaiki, W. & Hemida, M. G. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (mers-cov): infection, immunological response, and vaccine development. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 6491738 (2019).

Schindewolf, C. & Menachery, V. D. Middle East respiratory syndrome vaccine candidates: cautious optimism. Viruses 11, 74 (2019).

Adney, D. R. et al. Efficacy of an adjuvanted middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein vaccine in dromedary camels and alpacas. Viruses 11, 212 (2019).

Hilgenfeld, R. & Peiris, M. From SARS to MERS: 10 years of research on highly pathogenic human coronaviruses. Antiviral Res. 100, 286–295 (2013).

World Health Organization. Draft of the Landscape of COVID-19 Candidate Vaccines. World Heal Organ. https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/novel-coronavirus-landscape-ncov.pdf?ua=1 (WHO, 2020).

Chen, W. H., Strych, U., Hotez, P. J. & Bottazzi, M. E. The SARS-CoV-2 vaccine pipeline: an overview. Curr. Trop Med. Rep. 1–4 (2020).

Funk, C. D., Laferrière, C. & Ardakani, A. A snapshot of the global race for vaccines targeting SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 1–17 (2020).

Lambert, P. H. et al. Consensus summary report for CEPI/BC March 12-13, 2020 meeting: assessment of risk of disease enhancement with COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine 38, 4783–4791 (2020).

Lindsley, A. W., Schwartz, J. T. & Rothenberg, M. E. Eosinophil responses during COVID-19 infections and coronavirus vaccination. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 146, 1–7 (2020).

Zhu, F.-C. et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus type-5 vectored COVID-19 vaccine: a dose-escalation, open-label, non-randomised, first-in-human trial. Lancet 395, 1845–1854 (2020).

Zhu, F. C. et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a recombinant adenovirus type-5-vectored COVID-19 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18 years or older: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 396, 479–488 (2020).

Logunov, D. Y. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine in two formulations: two open, non-randomised phase 1/2 studies from Russia. Lancet 396, 887–897 (2020).

Logunov, D. Y. et al. Safety and efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet 397, 671–681 (2021).

Sadoff, J. et al. Interim results of a phase 1-2a trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2034201 (2021).

Folegatti, P. M. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 396, 467–478 (2020).

Ramasamy, M. N. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 396, 1979–1993 (2020).

Voysey, M. et al. Single-dose administration and the influence of the timing of the booster dose on immunogenicity and efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine: a pooled analysis of four randomised trials. Lancet 397, 881–891 (2021).

Voysey, M. et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1 (2021).

Folegatti, P. M. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a candidate Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus viral-vectored vaccine: a dose-escalation, open-label, non-randomised, uncontrolled, phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3099, 1–11 (2020).

Jackson, L. A. et al. An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32663912 (2020).

Anderson, E. J. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2427–2438 (2020).

Chu, L. et al. A preliminary report of a randomized controlled phase 2 trial of the safety and immunogenicity of mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Vaccine https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.007 (2021).

Baden, L. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2035389 (2020).

Walsh, E. E. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based Covid-19 vaccine candidates. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2439–2450 (2020).

Mulligan, M. J. et al. Phase I/II study of COVID-19 RNA vaccine BNT162b1 in adults. Nature 586, 589–593 (2020).

Sahin, U. et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T cell responses. Nature 586, 594–599 (2020).

Polack, F. P. et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2603–2615 (2020).

Che, Y. et al. Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of an inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccine in healthy adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1703 (2020).

Xia, S. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBIBP-CorV: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 39–51 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18-59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30843-4 (2021).

Wu, Z. et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARSCoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac) in healthy adults aged 60 years and older: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 181–192 (2021).

Ella, R. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBV152: a double-blind, randomised, phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30942-7 (2021).

Ella, R. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBV152: interim results from a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, phase 2 trial, and 3-month follow-up of a double-blind, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00070-0 (2021).

Xia, S. et al. Effect of an inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 on safety and immunogenicity outcomes: interim analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 324, 951–960 (2020).

Keech, C. et al. Phase 1–2 trial of a SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein nanoparticle vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2320–2332 (2020).

Tebas, P. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of INO-4800 DNA vaccine against SARS- CoV-2: a preliminary report of an open-label, Phase 1 clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine 31, 100689 (2021).

Richmond, P. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of S-Trimer (SCB-2019), a protein subunit vaccine candidate for COVID-19 in healthy adults: a phase 1, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 397, 682–694 (2021).

Koch, T. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a modified vaccinia virus Ankara vector vaccine candidate for Middle East respiratory syndrome: an open-label, phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 827–838 (2020).

Martin, J. E. et al. A SARS DNA vaccine induces neutralizing antibody and cellular immune responses in healthy adults in a Phase I clinical trial. Vaccine 26, 6338–6343 (2008).

Lin, J. T. et al. Safety and immunogenicity from a Phase I trial of inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine. Antivir Ther. 12, 1107–1113 (2007).

Modjarrad, K. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an anti-Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus DNA vaccine: a phase 1, open-label, single-arm, dose-escalation trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 19, 1013–1022 (2019).

Mercado, N. B. et al. Single-shot Ad26 vaccine protects against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature 586, 583–588 (2020).

van Doremalen, N. et al. ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine prevents SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in rhesus macaques. Nature 586, 578–582 (2020).

Corbett, K. S. et al. Evaluation of the mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in nonhuman primates. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1544–1555 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate, BBIBP-CorV, with potent protection against SARS-CoV-2. Cell 182, 713–721.e9 (2020).

Gao, Q. et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science 369, 77–81 (2020).

Guebre-Xabier, M. et al. NVX-CoV2373 vaccine protects cynomolgus macaque upper and lower airways against SARS-CoV-2 challenge. Vaccine 38, 7892–7896 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. A vaccine targeting the RBD of the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 induces protective immunity. Nature 586, 572–577 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Evaluation of candidate vaccine approaches for MERS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–11 (2015).

Yu, J. et al. DNA vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Science 6284, eabc6284 (2020).

Erasmus, J. H. et al. An alphavirus-derived replicon RNA vaccine induces SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody and T cell responses in mice and nonhuman primates. Sci. Transl. Med. 9396, 1–17 (2020).

Muthumani, K. et al. A synthetic consensus anti–spike protein DNA vaccine induces protective immunity against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in nonhuman primates. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 1–29 (2015).

Kobinger, G. P. et al. Adenovirus-based vaccine prevents pneumonia in ferrets challenged with the SARS coronavirus and stimulates robust immune responses in macaques. Vaccine 25, 5220–5231 (2007).

Qin, E. et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy in monkeys of purified inactivated Vero-cell SARS vaccine. Vaccine 24, 1028–1034 (2006).

Zhou, J. et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and protective efficacy of an inactivatedSARS-associated coronavirus vaccine in rhesus monkeys. Vaccine 23, 3202–3209 (2005).

Ren, W. et al. Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike S1-Fc fusion protein induced high levels of neutralizing responses in nonhuman primates. Vaccine 38, 5653–5658 (2020).

Zhang, N.-N. et al. A thermostable mRNA vaccine against COVID-19. Cell 182, 1271–1283.e16 (2020).

Lan, J. et al. Recombinant receptor binding domain protein induces partial protective immunity in rhesus macaques against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus challenge. EBioMedicine 2, 1438–1446 (2015).

Sanchez-Felipe, L. et al. A single-dose live-attenuated YF17D-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidate. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-3035-9 (2020).

Bukreyev, A. et al. Mucosal immunisation of African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) with an attenuated parainfluenza virus expressing the SARS coronavirus spike protein for the prevention of SARS. Lancet 363, 2122–2127 (2004).

Feng, L. et al. An adenovirus-vectored COVID-19 vaccine confers protection from SARS-COV-2 challenge in rhesus macaques. Nat. Commun. 11, 4207 (2020).

Chen, Z. et al. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing the spike glycoprotein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus induces protective neutralizing antibodies primarily targeting the receptor binding region. J. Virol. 79, 2678–2688 (2005).

Liu, R. et al. A recombinant VSV-vectored MERS-CoV vaccine induces neutralizing antibody and T cell responses in rhesus monkeys after single dose immunization Renqiang. Antiviral Res. 150, 30–38 (2018).

Wang, C. et al. MERS-CoV virus-like particles produced in insect cells induce specific humoural and cellular immunity in rhesus macaques. Oncotarget 8, 12686–12694 (2017).

Altmann, D. M., Douek, D. C. & Boyton, R. J. What policy makers need to know about COVID-19 protective immunity. Lancet 395, 1527–1529 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Anti–spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI Insight 4, e123158 (2015).

Tseng, C. Te, et al. Immunization with SARS coronavirus vaccines leads to pulmonary immunopathology on challenge with the SARS virus. PLoS ONE 7, e35421 (2012).

Castells, M. C. & Phillips, E. J. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 643–649 (2020).

Shimabukuro, T. & Nair, N. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 325, 780–781 (2020).

Schultz, N. H. et al. Thrombosis and thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2104882 (2021).

Greinacher, A. et al Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2104840 (2021).

Muir, K. L., Kallam, A., Koepsell, S. A. & Gundabolu, K. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2105869 (2021).

Ewer, K. et al. A monovalent chimpanzee adenovirus Ebola vaccine boosted with MVA. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 1635–1646 (2016).

Coughlan, L. et al. Heterologous two-dose vaccination with simian adenovirus and poxvirus vectors elicits long-lasting cellular immunity to influenza virus A in healthy adults. EBioMedicine 29, 146–154 (2018).

Wilkie, M. et al. A phase I trial evaluating the safety and immunogenicity of a candidate tuberculosis vaccination regimen, ChAdOx1 85A prime—MVA85A boost in healthy UK adults. Vaccine 38, 779–789 (2020).

Fausther-Bovendo, H. & Kobinger, G. P. Pre-existing immunity against Ad vectors humoral, cellular, and innate response, what’s important? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 10, 2875–2884 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. Neutralizing antibody responses to enterovirus and adenovirus in healthy adults in China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 3, e30 (2014).

Munster, V. J. et al. Respiratory disease and virus shedding in rhesus macaques inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 1. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.21.001628v1 (2020).

Bao, L. et al. Lack of reinfection in rhesus macaques infected with SARS-CoV-2. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.13.990226 (2020).

Darton, T. C. et al. Design, recruitment, and microbiological considerations in human challenge studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 15, 840–851 (2015).

Kristiansen, P. A. et al. WHO International Standard for anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00527-4 (2021).

Moher, D. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 4, 1–9 (2015).

Gross, L., Lhomme, E., Pasin, C., Richert, L. & Thiebaut, R. Ebola vaccine development: systematic review of pre-clinical and clinical studies, and meta-analysis of determinants of antibody response variability after vaccination. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 74, 83–96 (2018).

Acknowledgements

R.J.B. and D.M.A. are supported by MRC/UKRI and the Newton Fund (MR/S019553/1, MR/R02622X/1 and MR/V036939/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.M. developed the research, performed the systematic review and meta-analysis, carried out the statistical analyses, interpreted the data, generated figures and helped draft the manuscript. S.M.M. carried out statistical analyses, interpreted the data, generated figures and helped draft the manuscript. R.J.B. & D.M.A. conceived the study, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. R.J.B., C.J.R. and D.M.A. supervised the research. All authors revised the drafts and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

R.J.B. and D.M.A. are members of the Global T cell Expert Consortium and have consulted for Oxford Immunotec outside the submitted work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McDonald, I., Murray, S.M., Reynolds, C.J. et al. Comparative systematic review and meta-analysis of reactogenicity, immunogenicity and efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. npj Vaccines 6, 74 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-021-00336-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-021-00336-1

This article is cited by

-

Modelling the impact of hybrid immunity on future COVID-19 epidemic waves

BMC Infectious Diseases (2024)

-

Progress with COVID vaccine development and implementation

npj Vaccines (2024)

-

A quest for universal anti-SARS-CoV-2 T cell assay: systematic review, meta-analysis, and experimental validation

npj Vaccines (2024)

-

Short-term side effects of COVID-19 vaccines among healthcare workers: a multicenter study in Iran

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

The use of RNA-based treatments in the field of cancer immunotherapy

Molecular Cancer (2023)