Abstract

Rationale

Transient myopericarditis has been recognised as an uncommon and usually mild adverse event predominantly linked to mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines. These have mostly occurred in young males after the second dose of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines.

Objectives

Fulminant necrotising eosinophilic myocarditis triggered by a variety of drugs or vaccines is an extremely rare hypersensitivity reaction carrying a substantial mortality risk. Early recognition of this medical emergency may facilitate urgent hospital admission for investigation and treatment. Timely intervention can lead to complete cardiac recovery, but the non-specific clinical features and rarity make early diagnosis challenging.

Findings

The clinical and pathological observations from a case of fatal fulminant necrotising myocarditis in a 57-year-old woman, following the first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, are described. Other causes have been discounted with reasonable certainty.

Conclusion

These extremely rare vaccine-related adverse events are much less common than the risk of myocarditis and other lethal complications from COVID-19 infection. The benefits of vaccination far exceed the risks of COVID-19 infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, the agent responsible for COVID-19, has had a calamitous effect on the world. Recently, several COVID-19 vaccines have received emergency use authorisation. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine has now received full FDA approval for individuals over 12 years of age.

COVID-19 vaccines have been well tolerated apart from the expected local reactions at the injection site and mild transient constitutional symptoms, typical of vaccine systemic immune responses. Post-marketing surveillance has identified rare serious adverse events including vaccine-induced thrombosis and thrombocytopenia (VITT) with some adenovirus vaccines including the Astra-Zeneca (ChAdOx1-S) vaccine [1]. In addition to a small risk of VITT, the Janssen/Johnson and Johnson (Ad26.COV2.S) vaccine has also been associated with Guillain–Barre syndrome.

A small risk of anaphylaxis and mild transient myopericarditis, mostly in young males, has been observed predominantly with mRNA vaccines [2, 3]. Life-threatening fulminant necrotising eosinophilic myocarditis, an extremely rare idiosyncratic reaction, has been described with drugs and other vaccines. [4] The clinical features and immunopathology of a case of fatal fulminant necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis, following the first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, are described in this report. This rarer, much more severe hypersensitivity reaction is fundamentally different from the mild self-limited myopericarditis seen usually after the second dose of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines [2, 5]. These exceptionally rare events must be seen in the context of COVID-19 infection, which carries a far higher risk of myocarditis and other potentially lethal complications. [6]

Case Description

A previously well 57-year-old woman received the first Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in July 2021. The following day she experienced increasing lethargy and had to leave work early because of worsening fatigue. She had one episode of breathlessness and complained of a stiff neck as well as upper limb pain. She had a sore throat but pointed to her sternum. During the remainder of the day, she became increasingly unwell. The following day she consulted her primary care physician with a sore throat, back pain, fatigue and an episode of haematuria, which had occurred the previous night. She had difficulty getting out of the car and experienced a fall at the family physician’s surgery. She did not complain of palpitations.

On day 2, a complete blood count (CBC) was normal but she was noted to have an increased C-reactive protein (CRP) (Table 1). She had a raised ferritin and alanine transaminase (ALT) but the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was not undertaken, although the other liver enzymes were normal. There was no eosinophilia. On the third day, she was diagnosed with an Escherichia coli urinary tract infection, which was treated with trimethoprim. During that night, she was found deceased in bed. Apart from long-term omeprazole and the recently commenced trimethoprim, she was on no other treatment. There was no history of autoimmunity or allergic disease.

Autopsy Findings

The body was that of a small-built adult female of Chinese descent, consistent with the stated age of 57 years (height 155 cm; weight 40 kg). External examination was unremarkable. On internal examination, the most striking finding was a tan, solid lobulated mass originating from the mediastinum and situated in the left pleural cavity (Fig. 1, top left and top right). This mass was 130 × 120 × 90 mm and weighed 710 g. Mild splenomegaly (240 g) was noted. There was no pericardial effusion and there was no intracardiac thrombosis. The remainder of the autopsy examination was unremarkable. There were no abnormalities of other organs.

Top left: Left pleural mass originating from the mediastinum. Top right: Cut section of thymoma. Bottom left: × 20 magnification showing multifocal inflammatory cell infiltration in the myocardium; asterisk (*) showing areas of eosinophil-rich inflammatory aggregates with myococyte necrosis. Bottom right: × 40 magnification showing an abundant eosinophilic infiltrate with myocyte necrosis. Arrow shows an eosinophil, asterisk (*) showing myocyte necrosis

Histology and Ancillary Tests

Histological examination of the heart sections showed fulminant necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis (Fig. 1, bottom left and bottom right). There were multifocal aggregates of lymphoid cells, histiocytes and abundant eosinophils with focal myocyte necrosis in the free walls of both ventricles, inter-ventricular septum and around the conduction system (sino-atrial and atrio-ventricular nodes). No parasitic organisms or giant cells were identified. The eosinophilic infiltrate would make autoimmune myocarditis less likely. There was no evidence of eosinophils in other organs or eosinophilic vasculitis. Histological examination of the left pleural space mass showed a thymoma, WHO subtype AB.

There was a limited amount of post mortem serum for diagnostic studies. Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 were negative on histological paraffin blocks and she had a mild reduction in IgG 4.54 (7–14 g/L), IgA 0.72 (0.8–4.0 g/L) and IgM 0.26 (0.4–2.5 g/L) levels, post mortem. T cell receptor excision circle numbers from peripheral blood DNA were normal, as was a tryptase level. She had a borderline parvovirus PCR test from the myocardium, below quantifiable levels. Other viral PCR tests including enterovirus, metapneumovirus, parainfluenza (1–4), rhinovirus, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, SARS-CoV-2, parechovirus and influenza A and B were negative. A toxicology screen was negative. Complement studies and cytokine studies were not undertaken as there was no ante-mortem blood available.

Discussion

Fulminant necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis is an extremely rare hypersensitivity syndrome caused by a variety of drugs and vaccines [4]. This life-threatening idiosyncratic reaction specifically targets the myocardium. The cardiac injury is likely to be mediated by the highly toxic contents of granules including eosinophilic cationic protein, eosinophil major basic protein, eosinophil peroxidase and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin. In mice, eosinophil-derived IL4 plays a critical role in cardiac damage. [7]

The immunopathology of this extremely rare disorder remains to be defined but is likely to be mediated by cytotoxic T cells producing IL5. In the future, staining for IL5-producing T cells may be helpful in confirming this hypothesis. It is also possible these T cells have specific homing receptors for the heart. Single-cell RNA profiling may also help identify such cells but was not possible in this case because of post mortem RNA degradation. Cardiac myocytes express ACE2 receptors, which could bind the spike glycoprotein, translated from the mRNA vaccine. A specific ACE2-induced hypersensitivity reaction would not explain the pathogenesis of this disorder, given it can be triggered by other drugs and vaccines. In contrast to most other immune-mediated hypersensitivity disorders, a priming exposure may not be required since fulminant necrotising eosinophilic myocarditis can occur after the first exposure to a drug or vaccine. [4]

There was no family history of premature cardiac disease. Other first-degree family members have tolerated the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine without any significant adverse events. This would make a genetic drug hypersensitivity disorder to the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine less likely.

It is very unlikely the trimethoprim, begun a few hours before death, was responsible for the disorder as the patient was already acutely unwell for over 48 h prior to commencing treatment. Trimethoprim has not been associated with fulminant eosinophilic myocarditis. Given the benign CBC and modestly elevated CRP, it is unlikely sepsis that caused cardiovascular collapse. The urine infection contributed to the diagnostic confusion but is also unlikely to have been a factor in the fulminant necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis. The elevated ALT, ferritin and splenomegaly and reduced protein parameters were likely part of the acute inflammatory reaction. The brief haematuria is likely to have been a result of the UTI. The borderline parvovirus PCR is unlikely to be of significance as no giant cells or inclusion bodies were noted at autopsy. Only a high copy number (> 500) in myocardial tissues are considered causal. [8] COVID-19 serology and RT-qPCR tests from the myocardium were negative. NZ had been completely free from COVID-19 for many months at the time of her death.

The patient was noted to have an incidental thymoma at autopsy. Myocarditis has been described in patients suffering from WHO type B thymomas [9]. Ryanodine receptor antibodies may have a pathogenic role in such patients. [10] These patients however have lymphocytic or giant cell myocarditis, not seen in this case. It was also unlikely this patient had Good’s syndrome (thymoma associated with immunodeficiency). In contrast to this patient, the great majority of patients with Good’s syndrome are symptomatic, with recurrent infections or autoimmunity [11]. Most patients with Good’s syndrome have markedly reduced immunoglobulin levels [12]. The mild reduction in the post mortem IgG, IgA and IgM is likely to be an artefact [13]. In contrast to this patient, the majority of patients with Good’s syndrome have haematological abnormalities (Table 1). [14] Furthermore, the presence of a severe T cell defect in Good’s syndrome would have made an eosinophilic hypersensitivity response less likely, as IL5 plays a critical role in eosinophil biology.

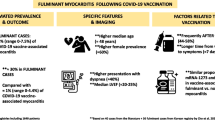

Globally, there are rare case reports of possible fulminant myocarditis, including fatalities, following mRNA vaccines, attesting to the extreme rarity of these reactions [15, 16]. Histological features showed an inflammatory infiltrate composed of T cells and macrophages, eosinophils, B cells and plasma cells. These cases were however not identified as fulminant necrotising eosinophilic myocarditis. The clinical and immunological differences between milder cases and fulminant cases were not explored in detail (Table 2).

Milder cases have occurred mostly in adolescent males usually after the second dose of an mRNA vaccine and have resolved spontaneously [22, 23]. Transient myopericarditis has less commonly occurred after the first dose, often in patients who have previously suffered COVID-19 infection, indicating the need for immunological priming [19, 21]. Although rarely biopsied, it appears these patients have lymphocyte predominant myocarditis [21]. Deaths are exceptionally rare and the histology is distinct from fulminant necrotising eosinophilic myocarditis [24]. Although less frequently described with the Janssen/Johnson and Johnson vaccine, these milder cases appear to be a specific hypersensitivity reaction to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table 2). [25].

Fulminant necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis progresses in three clinical stages. Many cases are fatal in the acute stage. A review of fulminant necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis showed cardiac arrest in almost one-half of patients and high in-hospital mortality with rates of 36.1%. [4] In addition to systemic steroids, many patients have required mechanical cardiac assistance in the acute phase. Early diagnosis and treatment with systemic steroids has however resulted in complete cardiac recovery in the majority of individuals. [4]

Untreated survivors may progress to a second clinical stage where there is increased risk of cardiac thromboembolic events. A third clinical stage comprises endomyocardial fibrosis leading to a chronic restrictive cardiomyopathy.

In up to 25% of fulminant necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis cases, there is no eosinophilia in the blood or in other organs. [4] This distinguishes the condition from other causes of eosinophilic myocarditis such as Loeffler’s syndrome or eosinophilic granulomatosis and polyangiitis (EGPA). There was no evidence of eosinophilic vasculitis at autopsy.

Diagnosing fulminant necrotising eosinophilic myocarditis is challenging given its rarity and non-specific presentation. Most patients experiencing mild constitutional symptoms following COVID-19 vaccines improve by 48 h. If patients become progressively unwell beyond this time, following the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, they should be carefully reviewed for vaccine complications as well as other co-incidental disorders. Severe chest pain may be less common in cases of fulminant necrotising eosinophilic myocarditis compared to the transient myopericarditis occurring in young males (Table 2) [4, 19]. The characteristic chest pain in younger males may reflect high rates of concomitant pericarditis. [20].

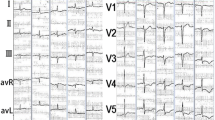

In cases of fulminant necrotising eosinophilic myocarditis, there may be electrocardiographic changes and an increase in troponin levels and echocardiography studies may show systolic and diastolic myocardial dysfunction [4]. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging may show late gadolinium enhancement but this is not specific for fulminant necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis. A diagnosis of fulminant necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis requires an endomyocardial biopsy, acknowledging the disease process may be uneven. [4]

Early admission to an intensive care or coronary care unit may facilitate diagnosis and treatment. If there are delays in obtaining an endomyocardial biopsy, or if negative despite high clinical suspicion, consideration should be given to pulse intravenous methylprednisolone treatment as well as mechanical cardiac assistance, if required. Apart from high-dose systemic corticosteroids, IL5 inhibitors such mepolizumab may have an important therapeutic role in treating fulminant necrotising eosinophilic myocarditis. [26].

It seems probable the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was responsible for the fatal fulminant necrotizing myocarditis in this case. The temporal association is compatible with such a hypersensitivity reaction, other causes have been excluded, and the histomorphology is consistent with the diagnosis. These are extremely rare adverse events and the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination far exceed the risks of COVID-19 infection [18]. COVID-19 infection carries a much higher rate of acute and chronic cardiovascular sequelae including myocarditis, arrhythmias and myocardial infarction and thromboembolic events (Table 2), which can be mitigated by COVID-19 vaccination. [3, 6, 17].

Data Availability

Data and material are available upon request

References

Perry RJ, Tamborska A, Singh B, Craven B, Marigold R, Arthur-Farraj P, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis after vaccination against COVID-19 in the UK: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:1147–56.

Bozkurt B, Kamat I, Hotez PJ. Myocarditis with COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. Circulation. 2021;144:471–84.

Barda N, Dagan NA-O, Ben-Shlomo Y, Kepten E, Waxman J, Ohana R, et al. Safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a nationwide setting. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1412–23. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2110475.

Brambatti M, Matassini MV, Adler ED, Klingel K, Camici PG, Ammirati E. Eosinophilic myocarditis: characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2363–75.

Muthukumar A, Narasimhan M, Li QZ, Mahimainathan L, Hitto I, Fuda F, et al. In-depth evaluation of a case of presumed myocarditis after the second dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Circulation. 2021;144:487–98.

Singer Me Auid- Orcid: --- Fau - Taub IB, Taub Ib Auid- Orcid: --- Fau - Kaelber DC, Kaelber DA-O. Risk of myocarditis from COVID-19 infection in people under age 20: a population-based analysis. 2021.07.23.21260998 [pii] https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.23.21260998. In press 2021.

Diny NL, Baldeviano GC, Talor MV, Barin JG, Ong S, Bedja D, et al. Eosinophil-derived IL-4 drives progression of myocarditis to inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy. J Exp Med. 2017;214:943–57.

Tschope C, Ammirati E, Bozkurt B, Caforio ALP, Cooper LT, Felix SB, et al. Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: current evidence and future directions. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18:169–93.

Shi Y, Wang C. When the Good Syndrome Goes Bad: A Systematic Literature Review. Front Immunol. 2021;12:679556. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.679556.

Goldberger A, Morneau K, Sansoucy B, Clarke N, Higgins J. Clinical testing for titin and ryanodine receptor autoantibodies in myasthenia gravis patients (P1.123). Neurology. 2017;88:P1.123.

Zaman M, Huissoon A, Buckland M, Patel S, Alachkar H, Edgar JD, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of seventy-eight UK patients with Good’s syndrome (thymoma and hypogammaglobulinaemia).

Malphettes M, Gerard L, Galicier L, Boutboul D, Asli B, Szalat R, et al. Good syndrome: an adult-onset immunodeficiency remarkable for its high incidence of invasive infections and autoimmune complications. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:e13–9.

Larscheid G, Schulz T, Herbst H, Trogel T, Eulert S, Pruss A, et al. Comparison of total immunoglobulin G in ante- and postmortem blood samples from tissue donors. Transfus Med Hemother. 2021;48:32–8.

Joven MH, Palalay MP, Sonido CY. Case report and literature review on Good’s syndrome, a form of acquired immunodeficiency associated with thymomas. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72:56–62.

Abbate A, Gavin J, Madanchi N, Kim C, Shah PR, Klein K, et al. Fulminant myocarditis and systemic hyperinflammation temporally associated with BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in two patients. Int J Cardiol. 2021;340:119–21.

Verma AK, Lavine KJ, Lin CY. Myocarditis after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1332–4.

Italia L, Ingallina G, Napolano A, Boccellino A, Belli M, Cannata FA-O, et al. Subclinical myocardial dysfunction in patients recovered from COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/echo.15215.

Gargano JW, Wallace M, Hadler SC, Langley G, Su JR, Oster ME, Broder KR, et al. Use of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine after reports of myocarditis among vaccine recipients: update from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, June 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(977):82.

Montgomery J, Ryan M, Engler R, Hoffman D, McClenathan B, Collins L, et al. Myocarditis following immunization with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in members of the US military. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1202–6.

Dionne A, Sperotto F, Chamberlain S, Baker AL, Powell AJ, Prakash A, Castellanos DA, Saleeb SF, de Ferranti SD, Newburger JW, Friedman KG. Association of Myocarditis With BNT162b2 Messenger RNA COVID-19 Vaccine in a Case Series of Children. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;10:e213471. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2021.3471.

Nguyen TD, Mall G, Westphal JG, Weingärtner O, Möbius-Winkler S, Schulze PC. Acute myocarditis after COVID-19 vaccination with mRNA-1273 in a patient with former SARS-CoV-2 infection. ESC Heart Fail. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.13613.

Abu Mouch S, Roguin A, Hellou E, Ishai A, Shoshan U, Mahamid L, Zoabi M, Aisman M, Goldschmid N, Berar Yanay N. Myocarditis following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. Vaccine. 2021;39(29):3790–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.087.

Salah HM, Mehta JL. COVID-19 Vaccine and Myocarditis. Am J Cardiol. 2021;157:146–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.07.009.

Choi SA-O, Lee SA-O, Seo JA-O, Kim MA-O, Jeon YA-O, Park JA-O, et al. Myocarditis-induced sudden death after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in Korea: case report focusing on histopathological findings.

Diaz GA, Parsons GT, Gering SK, Meier AR, Hutchinson IV, Robicsek A. Myocarditis and pericarditis after vaccination for COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.13443 e2113443. JAMA Cardiol 2021.

Song T, Jones DM, Homsi Y. Therapeutic effect of anti-IL-5 on eosinophilic myocarditis with large pericardial effusion. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2016218992. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-218992.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Coroner and family of the deceased in approving and consenting for this manuscript to be submitted. The family wish to increase awareness of fulminant necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis as a very rare hypersensitivity disorder requiring urgent assessment and treatment. The NZ Ministry of Health has been made aware of this information. We thank colleagues in the Department of Clinical Immunology, Auckland Hospital for their valuable comments. The authors would like to thank Drs. Daniela Vogel, Nicky Kingston, Jan Serfontein and Emily Carr-Boyd (LabPLUS, Auckland City Hospital) in consulting and reviewing the histological sections of the haematopoietic system; and Doctors Paul Morrow, Kilak Kesha and Charley Glenn (North Forensic Pathology Service) in reviewing the case. Also we would like to thank the technical and administrative staff at LabPLUS, Auckland City Hospital and toxicologists at the institute of Environmental Science and Research Limited.

Funding

BO was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Reasearch (BMBF) within the DEFEAT PANDEMIcs project (01KX2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RA: conception of the work and drafting the article, data analysis and interpretation, submission of the article

SW: data analysis and interpretation, critical review of the article

MS: data analysis and interpretation

JH, BO, CW, RA: data analysis and interpretation, critical review of the article

MT: data collection, data analysis and interpretation, critical review of the article

SS: data analysis and interpretation, critical review of the article

RT: data analysis and interpretation, conception of the work, final approval of the article

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This manuscript is categorised under public health surveillance and ethics approval was waived by the Research Office of Auckland District Health Board

Consent to Participate

Not applicable

Consent for Publication

The office of the chief Coroner and family of the deceased approves and consents this manuscript to be submitted and published.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ameratunga, R., Woon, ST., Sheppard, M.N. et al. First Identified Case of Fatal Fulminant Necrotizing Eosinophilic Myocarditis Following the Initial Dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine (BNT162b2, Comirnaty): an Extremely Rare Idiosyncratic Hypersensitivity Reaction. J Clin Immunol 42, 441–447 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-021-01187-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-021-01187-0