Abstract

Background

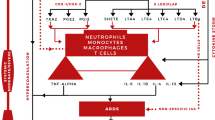

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes pulmonary injury or multiple-organ injury by various pathological pathways. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) is a key factor that is released during SARS-CoV-2 infection. TGF-β, by internalization of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), suppresses the anti-oxidant system, downregulates the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), and activates the plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) and nuclear factor-kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB). These changes cause inflammation and lung injury along with coagulopathy. Moreover, reactive oxygen species play a significant role in lung injury, which levels up during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Drug Suggestion

Pirfenidone is an anti-fibrotic drug with an anti-oxidant activity that can prevent lung injury during SARS-CoV-2 infection by blocking the maturation process of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and enhancing the protective role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). Pirfenidone is a safe drug for patients with hypertension or diabetes and its side effect tolerated well.

Conclusion

The drug as a theoretical perspective may be an effective and safe choice for suppressing the inflammatory response during COVID-19. The recommendation would be a combination of pirfenidone and N-acetylcysteine to achieve maximum benefit during SARS-CoV-2 treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) originated in Wuhan, Hubei Province, Central China, and quickly spread worldwide [1]. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the causative agent of COVID-19. Infection of the respiratory system by the virus results in pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [2]. ARDS is a potent factor associated with the mortality of COVID-19 patients. Currently, no specific therapeutic regimen has been approved for COVID-19, and all current treatments are merely supportive [3].

COVID-19 is divided into three stages. The early stage is the incubation period, which occurs along with asymptomatic or asymptomatic periods. In the second stage, non-severe symptomatic illness is observed. The period of infection in 80% of the patients is completed in this stage. The last stage is the hyperinflammatory phase in which cytokine storm and diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) are seen [4].

DAD is a histological hallmark for the acute phase of ARDS [5] and is divided into two phases. In the acute phase, oedema and hyaline membrane formation are observed. Furthermore, interstitial fibrosis can be seen in this stage. In the organizing phase, interstitial fibrosis and alveolar hyperplasia are noted [6]. Formation of active myofibroblasts increases the accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM), prevents alveolar re-epithelization, and causes the destruction of normal lung construction, thereby resulting in lung fibrosis. Overexpression and release of growth factors and cytokines by the injured cells and immune cells ensue when lung fibrosis occurs [7, 8]. Theoretically, this article attempts to provide a rational treatment to prevent or reducing lung injury by COVID19 infection.

Pathological role of TGF-β in SARS-CoV-2 infection

One of the critical growth factors released during SARS-CoV-2 infection is the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), which also plays a vital role in lung fibrosis. SARS-CoV-2 infection in some patients causes acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and TGF-β is an essential factor that accumulates in the lavage fluid of patients with ARDS and can be used as a therapeutic target [7, 9,10,11].

Literature evidence shows three possibilities for the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and TGF-β. The first possible mechanism is the release of TGF-β from immune cells such as neutrophils or injured cells due to SARS-CoV-2 infection [7, 12, 13]. Also, several data from other studies assert that the mRNA expression of TGF-β [14] and the protein level of TGF-β increase in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1) infected-lung cells [7] as well as in the plasma and lung tissues during the early phase of the infection [15, 16]. Recently, researchers have demonstrated similar results for SARS-CoV-2. The expression of the mRNA of TGF-β and TGF-β protein and its signaling pathway activity increases in SARS-CoV-2 infection [17,18,19].

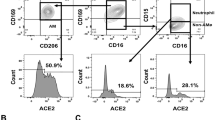

A second possible mechanism is that the SARS viruses (SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2) upregulate TGF-β by downregulating angiotensin-converting enzyme 2(ACE2) receptor via the interaction of the spike protein with ACE2. In the subsequent downregulation of ACE2, the level of angiotensin-II (ANG-II) increases. Furthermore, ANG-II enhances intracellular SMAD2 and SMAD4. Thus, TGF-β/SMAD signaling activity is hiked [7, 20,21,22,23].

The nucleocapsid (N) protein of SARS-CoV-2 may be considered as a third possibility. The N protein of SARS-Covid-1 causes a surge in the signaling pathway activity of TGF-β by interaction with SMAD3. Eventually, the SMAD3-P300 complex is formed, and now, SMAD3 is ready for interaction with SMAD4 [24, 25]. Data analysis by Chatterjee et al. revealed that the N protein of SARS-Covid-1 contains 423 amino acids, and that SARS-CoV-2 has 420 amino acids. Therefore, the pairwise identity between the N proteins of SARS-Covid and SARS-CoV-2 is around 88.3% [26]. Consequently, as a possible hypothesis, it is not surprising if the N protein of SARS-CoV-2 causes the formation of a complex of SMAD-p300; however, more research is needed. For an enhanced understanding of the role of TGF-β in SARS-CoV-2 infection, we divided the mechanism of TGF-β into two parts. The first pathway describes the upregulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by TGF-β and its effects, and the second pathway includes the non-ROS pathways.

Pathways dependent on reactive oxygen species

A) Internalization of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC)

In the early stage of SARS, patients experience lung oedema. It has been found that the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) transfers sodium ions from outside the alveolar cells (alveolar space). Along with sodium ions, fluid also enters the cells. Thus, ENaC controls the oedema in the lung. During this activity, sodium potassium pump on the other side of the cells transfers the fluid in the cytoplasm of the cells to the interstitial space [27, 28]. TGF-β, by internalization of αβγ ENaC from the membranes of the alveolar epithelial cells, causes pulmonary oedema. The signaling pathways perform the internalization of ENaC via transforming growth factor-beta receptor 1 (Tgfbr1)/SMAD2/3 at the end of this pathway. This process produces a high concentration of ROS, which results in the internalization of ENaC [9]. TGF-β can be released from different cells (immune cells or epithelial cells) as a latent complex that is deactivated and stored in the ECM. This complex contains the active domain of TGF-β as well as the latency-associated protein (LAP) and latent TGF-β-binding protein (LTBP). LTBP makes the connection between the complex and ECM. LAP covers the active domain of TGF-β, which can be released by the matrix metalloproteinase and integrins ανβ6 and ανβ8 [9, 29,30,31,32,33]. After the active domain of TGF-β is released, its interaction with TGFβR1 activates the receptor. TGFβR1 phosphorylates SMAD2/3. Furthermore, SMAD2/3 activates phospholipase D (PLD) [9, 34]. Owing to the activity of PLD, phosphatidylcholine (PC) is hydrolyzed and gets converted to phosphatidic acid (PA) and choline [9, 35]. PA induces the activity of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type-1 alpha (PIP5K1α) [9], whose kinase activity converts phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PIP4P) to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns (4,5) P2) [8, 9]. PtdIns (4,5) P2 exhibits two activities; the first activity is a positive feedback by the activation of PLD1 [9, 36], and the second activity is the over-regulation of NADPH oxidase4 (NOX4) activity. NOX4 generates ROS. It has been observed that ROS reduces the surface stability of the beta subunit of ENaC, which causes the internalization of βENaC. PLD1 inhibits the expression of alpha subunits of ENaC. Additionally, the cell loses its ability to absorb extracellular sodium, and hence, alveolar oedema occurs [9, 28]. The upregulation of NOX4 via TGF-β signaling is not limited to SMAD/PLD pathways. One of the non-SMAD signaling pathways of TGF-β is the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) via interaction with TGFβR2. PI3K signaling affects several genes, and one of them is the NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) gene. Besides, in SMAD signaling of TGF-β, SMAD2 enhances the expression of NOX4 by interacting with the transcriptional factors [37, 38] (Fig. 1).

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) is activated and released from latency-associated protein (LAP) cover due to inflammatory response [31]. TGF-β binds to transforming growth factor-beta receptor (TGFβR1 and TGFβR2). TGFβR1 by SMAD2/3 causes the activation of phospholipase D (PLD1) [9, 34]. PLD1 decomposes phosphatidylcholine (PC) to phosphatidic acid (PA), and choline [9, 35]. PA activates phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type-1 alpha (PIP5K1α) [9]. PIP5K1α converts phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PIP4P) to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5) P2) [8, 9]. PtdIns(4,5) P2, by activation of NADPH oxidase4 (NOX4), increases ROS production. ROS causes internalization of the epithelial sodium channel (EnaC) [9, 28]. In addition, PtdIns(4,5) P2 has a positive feedback by activation of PLD1 [9, 36]. Also, TGFβR2 by co-operation with PI3K, increases the expression of NOX4 [37]. PLD1 too, by the effect on the gene, decreases the expression of the alpha subunit of EnaC. Non-functional EnaC causes pulmonary oedema [9]

B) Suppressing the anti-oxidant system

Suppressing the anti-oxidant systems by TGF-β is another way of upregulating the ROS. Oxidative stress plays a pathological role in lung inflammation and acute lung injury (ALI). Anti-oxidants provide defence against oxidative stress. One of the lung's critical anti-oxidants, which is downregulated by TGF-β, is glutathione (GSH). GSH is an anti-oxidant with multiple functions in the cells. Among all the functions, anti-oxidant defence of GSH is the most significant one [39]. GSH exhibits anti-oxidant properties by reducing hydrogen peroxide and lipid peroxide when GSH cysteine gets oxidized during peroxidase activity. Downregulation of GSH has been observed in fibrotic disease, including cystic fibrosis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [31, 32, 40,41,42,43,44]. In the epithelial lining fluid (ELF) of the lower respiratory tract, GSH is the first defence factor against oxidative stress. Inhalation of GSH is an effective treatment for various pulmonary diseases [45]. In lung inflammation, the neutrophils release hypochlorous acid (HOCl), which reacts with GSH secreted by the epithelial cells. Thus, GSH protects the epithelial cells from HOCl [32]. In COVID-19, intravenous or oral administration of GSH is an effective treatment for cytokine storm syndrome and respiratory distress. This therapeutic effect of GSH is achieved by inhibiting TNF-α-induced NF-kappaB activation [46]. Furthermore, GSH exerts activity against viruses such as herpes by blocking their replication [47]. However, the antiviral activity of GSH on SARS-CoV-2 has not been confirmed till date. Glutamate and cysteine, in the presence of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase, get converted to gamma-glutamylcysteine. In the next step, gamma-glutamylcysteine is in turn converted to GSH due to glutathione synthase activity [48]. Arsalane et al. have shown that the potent inhibitory effect of TGF-β1 on gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase inhibits the synthesis of GSH in the lung epithelial cell line A549 [49]. Regeneration of GSH is done by glutathione reductase. Glutathione disulphide, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), and hydrogen ion in the presence of glutathione reductase yield two molecules of GSH and one molecule of NADP + [50] (Fig. 2).

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) inhibits gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase. Owing to this inhibition, glutathione (GSH) synthesis pathway is blocked and GSH level is decreased. Without anti-oxidant defence, lung cells are exposed to more injury [48]

Reactive oxygen species non-dependent pathways

This section discusses other cell and tissue injuries that are not dependent on reactive oxygen pathways.

A) Downregulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)

TGF-β can downregulate cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), which is located in the alveolar epithelial cell membrane. CFTR is a cAMP-regulated chloride channel which causes either secretion or absorption of chloride ions [28, 51, 52]. Its activity is critical in preventing pulmonary oedema [53]. In the alveolar epithelial cells (type I and II), it has been observed that CFTR channels, in the presence of cAMP, open and upregulate alveolar fluid clearance (AFC). The absence or lack of CFTR causes the failure of cAMP-stimulated fluid clearance from the distal air space; therefore, pulmonary oedema occurs. Inhibition of CFTR in mouse and human cells by molecules such as glibenclamide causes increased cAMP-stimulated fluid accumulation due to the inability of the CFTR to transfer chloride ions to the cells [53,54,55,56,57]. However, a single study has shown that paracellular transport between the alveolar epithelial cells is a significant way of transporting chloride [55].

Another role of CFTR is the secretion of bicarbonate from the epithelial cells either directly or indirectly [58]. Bicarbonate acts as a protective factor by controlling the pH of the lung. The airway becomes acidic, which causes lung injury. The acidic pH allows the easy development of viral infection. Besides, bicarbonate has chelating properties and can interact with calcium ion, which is an essential factor in the development of viral infections (when it is a free ion). Furthermore, bicarbonate, by decreasing calcium ion as a free ion and preventing lung acidification, protects the lung [59]. The normal pH of the airway surface liquid (ASL) is controlled by CFTR by transporting bicarbonate. Alkalization of ASL normalizes the pH [60]. Downregulation of CFTR also increases the expression of the high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1). HMGB1 interacts with Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), Toll-like receptor 4, and receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), which activates nuclear factor (NF)-κB. In the subsequent activation of NF-κB, pro-inflammatory cytokines are released. Inflammation pathways that are mediated by HMGB1 cause lung injury. This role of HMGB1 is important, as suggested for COVID-19 therapy [61]. More literature evidence regarding the relationship between CFTR and endothelial cells support this fact. Erfinanda et al. found that CFTR downregulation causes increased permeability of endothelial cells as well as enhanced permeability to chloride and calcium ions through deactivation of WNK lysine deficient protein kinase 1(WNK 1) and activation of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 4 (TRPV4) [62]. WNK1 acts as a regulatory factor for several ion channels and exerts an inhibitory effect on TRPV4 via decreased surface expression [63]. Based on studies performed by Erfinanda, it could be concluded that CFTR dysfunction causes downregulation of WNK1. A mechanism that can explain this phenomenon is, when CFTR disability or lower expression happens, intracellular chloride ion concentration increases due to decreased secretion of the ions [64]. The high chloride concentration causes inhibition of WNK1 [65]. However, no study has directly proved this phenomenon. TRPV4 expression has been reported in smooth muscle cells in the pulmonary aorta and artery and vascular endothelium. Its function is to cause an influx of calcium ions into the cells. The activity of TRPV4 results in dysfunction of the alveolar-capillary barrier and thereby increases its permeability. A possible mechanism of TRPV4 is increasing calcium and nitric oxide (NO) levels, which cause vasodilation and moderate vascular permeability [66,67,68]. Cruz has explained the mechanism by which TGF-β inhibits CFTR in the bronchial epithelial cells. TGF-β, after interacting with the TGF-beta receptor, stimulates intracellular trafficking of lemur tyrosine kinase 2 (LMTK2) via Rab11, which causes LMTK2 to be recycled and shifted to the cell membrane where LMTK2 phosphorylates serine-737 of CFTR and inhibits CFTR activity [69]. Kabir et al. have reported the effect of TGF-β on the expression of CFTR. The data showed that TGF-β elevates the level of mir-145 microRNA (miR-145) in the alveolar epithelial cells (AECs), which inhibits CFTR mRNA translation, affects the stability, and reduces the availability of the F508del CFTR substrate for lumacaftor corrector [70]. miR-145, by direct interaction with human CFTR mRNA at position 427–437, the 1557 bp long 3′-UTR (untranslated region), reduces the expression of CFTR protein [71, 72]. Supporting evidence has been found in the research by Mitash et al., which demonstrated that TGF-β1 causes an increased expression of CFTR inhibitors such as a miR-143 and miR-145 [73].

Yang established the role of miR-145 in lung fibroblasts and the formation of stress fibers. Overexpression of miR-145 has been reported in the pulmonary fibroblasts due to the activity of TGF-β1. Activation of miR145 by TGF-β1 causes the activation of the latent form of TGF-β1. The roles of miR-145 in the fibroblasts are the upregulation of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), moderate formation of focal and fibrillar adhesion, and increase in contractility [74]. Similar data published by Wei et al. have indicated that miR-145 is upregulated in human lung fibroblasts (HLF) via TGF-β [75]. Similar reports revealing the overexpression of α-SMA in fibrotic diseases such as lung fibrosis have been published by Whyte et al. and Ju. et al. [76, 77]. A possible mechanism of enhancing α-SMA by miR-145 is the inhibition of Krüppel-like factor-4 (KLF4), a negative regulator of α-SMA [78,79,80]. However, more information on the relationship between miR-145 and TGF-β1 is required, since sufficient data indicate that miR-145 plays a negative role in TGF-β1 via the inhibition of SMAD3 [81, 82] (Fig. 3).

Active transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) activates the transforming growth factor-beta receptor (TGFβR1 and TGFβR2). TGFβR1 and TGFβR2 downregulate the expression of CFTR [70]. On the other hand, co-operation with Rab11 causes the activation of lemur tyrosine kinase 2 (LIMK2). LIMK2 internalizes CFTR [69]. Non-functional CFTR cannot transfer chloride, and pulmonary oedema ensues [53]. Conversely, bicarbonate ions are unable to enter the cells, and the pH may be disturbed [58,59,60]

B) TGF-β activates plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1)

In the fibrosis of lung tissue, there is an increase in ECM production as well as a decrease in ECM degradation. One of the significant factors that inhibit ECM degradation is plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), which has a negative regulatory effect on plasminogen. Plasminogen, by its proteolytic activity, degrades ECM; however, due to the increased expression and activity of PAI-1, the proteolytic activity of plasminogen and ECM degradation decrease. A negative regulatory effect on plasminogen by PAI-1 occurs via the direct inhibition of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which prevents the conversion of plasminogen to the active form plasmin. Another role of plasminogen is its fibrinolytic property that prevents thrombosis. Thus, PAI-1 upregulation leads to the risk of thrombosis. The potency of PAI-1 activity in thrombosis is sufficient for the use PAI-1 inhibitors as therapeutic agents for thrombosis treatment [7, 83,84,85]. Furthermore, investigations have confirmed the critical role of PAI-1 in pulmonary coagulopathy [86, 87]. PAI-1 upregulation occurs in patients with SARS-CoV-1 infection due to TGF-β overexpression, which has been reported by Whyte. [76]. The same result has been obtained with regard to the elevation of PAI-1 in critically-ill and non-critically-ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection [88]. However, PAI-1 is a single factor for coagulopathy during SARS-CoV-2[89] (Fig. 4).

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) activates plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1). PAI-1 inhibits tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and prevents the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. This effect of TGF-β on PAI-1 may cause coagulopathy [83]

C) TGF-β activates nuclear factor-kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB)

NF-kB contains five members, namely NF-kB1 (P50), NF-kB2, RelA (P65), RelB, and c-Rel. In the normal condition, NF-kB along with nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cell inhibitor (IκB) forms inactive complexes in the cytoplasm of cells [90, 91]. In SARS-CoV-2 infection, NF-kB upregulates various cytokines and chemokines via the activity of angiotensin II receptor type-1 (AT1R), Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), interleukin receptor 1 (IL-1R), IL-6R, IL-18R, and interferon-gamma receptor (IFN-γ) [92]. TGF-β, by activation of tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factor 6(TRAF6), indirectly causes increased activity of NF-kB [93]. Yamashita et al. have shown the interaction of TGF-β with TGF-β receptor and that TRAF6 binds to TβRI and TβRII, with a slightly higher tendency toward the latter [94]. Binding of TRAF6 to activated TGF-β receptors increases the K63-linked polyubiquitination of TRAF6 [95]. The polyubiquitinated TRAF6 interacts with mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7-interacting protein 2 (MAP3K7IP2 or TAB2) and through it, connects with mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 (MAP3K7 or TAK1) [96, 97]. Formation of the complex of TRAF6 with TAK1 is necessary for the activation of TAK1. TAK1 activated IκB kinase (IKK) causes the activation of NF-kB by the disassociation of NF-kB/IκB complex [97,98,99] (Fig. 5).

Active transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) activates the transforming growth factor-beta receptor (TGFβR1 and TGFβR2). TGFβR1 and TGFβR2 cause activation of TRAF6, which subsequently activates TAB2. TAB2 activates TAK1, which in stimulates IκB kinase (IKK) and increases the dissociation of nuclear factor-kappa (NF-kB) from IκB. The free form of NF-kB is active and shows an inflammatory response [93,94,95,96,97,98,99]

Therapeutic role of pirfenidone by inhibition of TGF-β

Pirfenidone (5-methyl-1-phenyl-2-[1H]-pyridone) has anti-fibrotic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-oxidant properties. These properties of pirfenidone are due to its downregulatory effects on pro-inflammatory cytokines [100]. Pirfenidone-mediated anti-fibrotic processes occur in the lung, kidney, and liver [101]. One of the effective mechanisms of pirfenidone is the downregulation of TGF-β in gene expression at the transcriptional and translational levels [102]. This downregulatory effect is due to the direct inhibition of furin by pirfenidone [103,104,105]. TGF-β is synthesized in a precursor form in the cell, which needs furin activity for maturation [106]. Pre-pro-TGF-β contains a signal peptide (pre-region), latency-associated peptide (LAP, which is also called the pro-region), and TGF-β region. This complex, during the second stage, loses its pre-region. The other parts of the complex undergo dimerisation with another complex and low glycosylation to get converted to low glycosylated pro-TGF-β. In the next step, this low glycosylated pro-TGF-β is high glycosylated. The high glycosylated pro-TGF-β, with the cleavage activity of furin, gets converted to high glycosylated latent TGF-β and is then secreted from the cells [107,108,109]. Pirfenidone (by blocking furin) inhibits the conversion of high glycosylated pro-TGF-β to high glycosylated latent TGF-β (Fig. 6).

Pre-pro transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) loses its pre-region and gets converted to pro-TGF-β. Pro TGF-β, under glycosylation, gets converted to low glycosylated pro-TGF-β. The low glycosylated pro-TGF-β again undergoes glycosylation and is converted to high glycosylated pro-TGF-β. Furin cleaves the active region of TGF-β from the pro-region and forms latent TGF-β [106,107,108,109]. Pirfenidone at this stage stops the maturation of TGF-β by inhibition of furins [103,104,105]. After the formation of latent TGF-β, it is secreted outside the cells and the active form of TGF-β is released as shown in Fig. 1

Protective role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in SARS-CoV-2

PPARs contain PPARα, PPARβ/δ. and PPARγ, which are nuclear hormone receptors. One of the effects of PPARs is the suppression of inflammatory pathways [110]. PPARs, by moderating the activity of IκBα, inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway [111]. Agonistic effects of compounds such as pioglitazone on PPAR-γ investigated during COVID-19 have suggested that they might serve as novel therapeutic options for SARS-CoV-2 infection [112, 113]. Krönke et al. have confirmed that the activity of PPAR-γ and PPARα upregulate the expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in human vascular cells [114]. Cho et al. have performed investigations on human pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells, which imply that activated PPAR-γ, by interacting with PPAR response element (PPRE), increases the transcription of HO-1 [115]. HO-1 degrades free heme to carbon monoxide, biliverdin and ferrous iron [116]. The importance of the discussion on HO-1 is that hemolysis, hemoptysis, or rhabdomyolysis has been reported in patients with COVID-19, which increase the free-heme level. A high level of free heme stimulates inflammatory, thrombosis and oxidative pathways [117]. One of the main reasons for hyper inflammation in elderly patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection is the low expression of HO-1 [118]. On the other hand, metabolites of heme by HO-1 have a protective role in the lung tissue. CO, one of the metabolites of heme, has anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Investigations have alluded that CO lowers the production of cytokines in vitro. In vivo, CO acts as a protective agent in oxidative and inflammatory lung injury [119, 120]. The anti-inflammatory activity of CO is effective in preventing lung injury by decreasing TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [121]. Biliverdin also gets converted to bilirubin, an anti-oxidant, via biliverdin reductase (BVR) [117]. Conversely, Jiang, L et al. have shown that carbon monoxide-releasing molecule (CORM)-2 causes the upregulation of HO-1, which inhibits thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIPrx)/NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome pathway in LPS-induced acute lung injury [122]. In the presence of ROS, TXNIP is disassociated from Trx and binds to NLRP3. Interaction of TXNIP with NLRP3 causes the activation of NLRP3. It has been noted that HO-1, by decreasing ROS, inhibits the activation of NLRP3 [123]. By reducing the activity of NLRP3, maturation of IL-1β is disturbed [124]. In SARS-CoV-2 infection, mature IL-1β induces the inflammation of pulmonary tissue and fibrosis [125] (Fig. 7).

Pirfenidone activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (alpha and gamma) (PPAR) [111, 126]. PPAR activates PPAR response element (PPRE). PPRE increases the activity of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [115]. HO-1 coverts free heme to carbon monoxide (CO), ferrous iron, and biliverdin [116]. CO shows anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [119, 120]. Biliverdin is converted to bilirubin with the help of biliverdin reductase (BVR) and shows anti-oxidant activity [117]. Furthermore, pirfenidone, by blocking BTB domain and CNC homolog 1 (Bach1) increases the activity of anti-oxidant redox elements (ARE). ARE upregulates the expression of HO-1 and anti-oxidant system. By blocking TGF-β, pirfenidone indirectly activates nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Nrf2 activates ARE. Pirfenidone indirectly causes the dissociation of Nrf2 from KEAP1. The dissociated KEAP1 inhibits IκB kinase (IKK) and blocks the activity of nuclear factor-kappa (NF-kB) [127,128,129,130]

Therapeutic role of pirfenidone by PPARs and HO-1 in SARS-CoV-2 infection

Sandoval-Rodriguez et al. have established that prolonged-release pirfenidone upregulates PPAR-α signaling and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) via in vivo and in vitro studies performed in HepG2 cells of mice. Molecular docking analysis has also confirmed that pirfenidone is an agonistic ligand for PPAR-α [126]. However, the study investigated the positive regulatory effect of pirfenidone in HepG2 cells. These results and data support the hypothesis of pirfenidone’s agonistic effect on PPAR-α, which acts as an anti-inflammatory drug in pulmonary inflammation. Gutiérrez-Cuevas et al. have highlighted the role of prolonged-release pirfenidone as a potential cardioprotective agent via the overexpression of PPARα and PPARγ protein levels [111]. This research on pirfenidone's positive regulatory effect on hepatic and cardiac cells has shown the other pirfenidone mechanism. However, further studies are required to confirm the relationship between pirfenidone and PPARs, especially in lung inflammation.

Therapeutic role of pirfenidone by regulation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/BTB domain and CNC homolog 1 (Bach1)

Another function of pirfenidone is the regulation of Nrf2/Bach1 by inhibition of TGF-β1 activity. Nrf2, by binding to anti-oxidant redox elements (ARE), enhances the expression of anti-oxidants. ARE, by the action on particular genes, directly induces high anti-oxidant levels, HO-1 [127, 128]. ARE's impact is not limited, but this was not discussed as the scope of the article did not permit it. Nrf2 downregulates cytokine expression by blocking NF-kB signaling [128]. One possible inhibition mechanism is related to the dissociation of the Nrf2/Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) complex, which allows KEAP1 to inhibit IKK beta [129]. Thus, Nrf2 is an essential factor for controlling inflammation. Liu et al. have shown in bleomycin-induced mice with pulmonary fibrosis that pirfenidone increases the anti-oxidant expression through the regulation of Nrf2/Bach1. Bach1 is a transcription regulator protein that inhibits the interaction of Nrf2 with ARE due to its competitive inhibitory effect. Liu et al. have proven this in mouse lung fibroblasts (MLF) stimulated by TGF-β1. It has been observed that the mRNA expressions of Nrf2 and HO-1 were low, even though the mRNA expression of Bach1 was high. Pirfenidone (by inhibiting TGF-β1 activity) prevents the downregulation of Nrf2 and HO-1 and upregulation of Bach1 [130]. Liu et al. have found similar results in the lung tissues of mice with BLM (bleomycin)-induced pulmonary fibrosis after pirfenidone administration. It is worth mentioning that these two experiments though different show the same result [130] (Fig. 7).

Combination therapy with N-acetylcysteine (NAC)

NAC is a potent drug used in the treatment for COVID-19 due to the synthesis of GSH; besides, it exerts direct anti-oxidant activity and improves T-cell response [131]. As a hypothesis, we suggest the combination of NAC and pirfenidone to be a potent and effective in the treatment of patients with COVID-19. Studies by Shi et al. have revealed that the combination of these two drugs in patients with IPF did not affect the safety or efficacy when compared with single therapy of pirfenidone [132]. However, further investigation is needed in patients with COVID-19.

Adverse events and drug–drug interaction of pirfenidone

Gastrointestinal upset (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, decreased appetite, and constipation) and skin reaction (photosensitivity and rash) are the possible side effects of pirfenidone. Gastrointestinal adverse effects happened at the early stage of treatment and disappeared after the first 6 months. However, photosensitivity is more varied during the treatment period. During therapy, monitoring liver function is required [133,134,135]. Contraindication of therapy includes hypersensitivity to the drug and severe liver or kidney disease. Drug interactions that lead to increased serum concentration and increased drug toxicity should also be avoided. Grapefruit juice, fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, ciprofloxacin, paroxetine, amiodarone, and propafenone increase the bioavailability of pirfenidone [136]. Adverse reaction of drug during IPF treatment in several clinical research papers tolerated well [135, 137]. However, further studies are needed on other possible side effects of pirfenidone on COVID-19 patients.

Scope of treatment

Due to a lack of sufficient clinical information on the use of pirfenidone in COVID-19 patients, initiation of pirfenidone treatment was not specified. However, based on the uncertain response of patients to COVID-19 infection (due to severity of illness, age, and other risk factors) and chronic pulmonary involvement of patients after a period of disease [138, 139], we suggested that the best treatment period is from the beginning of the infection for at least 14 days or longer. This hypothesis is about the duration of treatment given according to the behavior of COVID-19 infection and the mechanism of drug action. To date, several clinical trials regarding the possible treatment of COVID-19 by pirfenidone are still under investigation.

Discussion

Pirfenidone, by inhibiting TGF-β, agonistic activity on PPARs and regulation of Nrf2/BTB domain and CNC homolog 1 (Bach1) increase the anti-oxidant activity of the body, reducing lung fibrosis and inflammation, and exert a potential therapeutic effect on COVID-19. The drug can reduce pulmonary oedema, decrease cytokine storm, and help lung tissue fight against inflammation pathways. For better results, it should be combined with N-acetylcysteine for maximum efficiency. Pirfenidone is well tolerated in a long course of treatment and it can be good choice for supportive treatment of COVID-19 during the infection period or even during recovery period. However, all these data are theoretical and need clinical research to prove the hypothesis.

Abbreviations

- ACE2:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- AEC:

-

Alveolar epithelial cells

- AFC:

-

Alveolar fluid clearance

- ALI:

-

Acute lung injury

- ANG-II:

-

Angiotensin-II

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ARE:

-

Anti-oxidant redox elements

- Bach1:

-

BTB domain and CNC homolog 1

- BVR:

-

Biliverdin reductase

- CFTR:

-

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CO:

-

Carbon monoxide

- CORM-2:

-

Carbon monoxide-releasing molecule-2

- DAD:

-

Diffuse alveolar damage

- ECM:

-

Extracellular matrix

- ENaC:

-

Epithelial sodium channel

- ELF:

-

Epithelial lining fluid

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- HLF:

-

Human lung fibroblast

- HMGB1:

-

High mobility group box-1

- HO-1:

-

Heme oxygenase-1

- HOCL:

-

Hypochlorous acid

- KEAP1:

-

NRF2/Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- KLF4:

-

Krüppel-like factor-4

- IFN-γ:

-

Interferon-gamma receptor

- IKK:

-

IκB kinase

- IL-1R:

-

Interleukin receptor 1

- IPF:

-

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- LAP:

-

Latency-associated protein

- LMTK2:

-

Lemur tyrosine kinase 2

- LTBP:

-

Latent TGF-β-binding protein

- NAC:

-

N-Acetylcysteine

- NADPH:

-

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NF-kB:

-

Nuclear factor-kappa

- NLRP3:

-

NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3

- NOX4:

-

NADPH oxidase4

- Nrf2:

-

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- MAP3K7IP2 or TAB2:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7-interacting protein 2

- MAP3K7 or TAK1:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7

- miR-145:

-

Mir-145 microRNA

- MLF:

-

Mouse long fibroblasts

- PA:

-

Phosphatidic acid

- PAI-1:

-

Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1

- PC:

-

Phosphatidylcholine

- PIP5K1α:

-

Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type-1 alpha

- PIP4P:

-

Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate

- PI3K:

-

NADPH oxidase4

- PLD:

-

Phospholipase D

- PPARs:

-

Peroxisome: proliferator-activated receptors

- PtdIns (4,5) P2:

-

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- RAGE:

-

Receptor for advanced glycation end products

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SIRT1:

-

Sirtuin 1

- TGF-β:

-

Transforming growth factor-beta

- Tgfbr1:

-

Transforming growth factor-beta receptor 1

- TLR2:

-

Toll-like receptor 2

- TRPV4:

-

Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 4

- tPA:

-

Tissue plasminogen activator

- TNFR:

-

Tumor necrosis factor receptor

- TXNIP:

-

Thioredoxin-interacting protein

References

Li H, Liu SM, Yu XH, Tang SL, Tang CK. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): current status and future perspectives. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(5):105951.

Ragab D, Salah Eldin H, Taeimah M, Khattab R, Salem R. The COVID-19 cytokine storm; what we know so far. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1446.

Lechowicz K, Drożdżal S, Machaj F, Rosik J, Szostak B, Zegan-Barańska M, et al. COVID-19: the potential treatment of pulmonary fibrosis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1917.

Calabrese LH. Cytokine storm and the prospects for immunotherapy with COVID-19. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020;87(7):389–93.

Cardinal-Fernández P, Lorente JA, Ballén-Barragán A, Matute-Bello G. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and diffuse alveolar damage. New insights on a complex relationship. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(6):844–50.

Kligerman SJ, Franks TJ, Galvin JR. From the radiologic pathology archives: organization and fibrosis as a response to lung injury in diffuse alveolar damage, organizing pneumonia, and acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia. Radiographics. 2013;33(7):1951–75.

Zuo W, Zhao X, Chen YG. SARS coronavirus and lung fibrosis. In: Molecular biology of the SARS-coronavirus Heidelberg. Berlin: Springer; 2010. p. 247–58.

Weber G, editor. Advances in enzyme regulation. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2003.

Peters DM, Vadász I, Wujak L, Wygrecka M, Olschewski A, Becker C, et al. TGF-β directs trafficking of the epithelial sodium channel ENaC which has implications for ion and fluid transport in acute lung injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(3):E374–83.

Frank JA, Matthay MA. TGF-β and lung fluid balance in ARDS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(3):885–6.

Dreher M, Kersten A, Bickenbach J, et al. The characteristics of 50 hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without ARDS. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(16):271–8.

Chen W. A potential treatment of COVID-19 with TGF-β blockade. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(11):1954–5.

Schönrich G, Raftery MJ, Samstag Y. Devilishly radical NETwork in COVID-19: oxidative stress, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and T cell suppression. Adv Biol Regul. 2020;77:100741.

Mirzaei H, Faghihloo E. Viruses as key modulators of the TGF-β pathway; a double-edged sword involved in cancer. Rev Med Virol. 2018;28(2):e1967.

Li SW, Wang CY, Jou YJ, Yang TC, Huang SH, Wan L, et al. SARS coronavirus papain-like protease induces Egr-1-dependent upregulation of TGF-β1 via ROS/p38 MAPK/STAT3 pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25754.

Lee CH, Chen RF, Liu JW, Yeh WT, Chang JC, Liu PM, et al. Altered p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase expression in different leukocytes with increment of immunosuppressive mediators in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. J Immunol. 2004;172(12):7841–7.

Xiong Y, Liu Y, Cao L, Wang D, Guo M, Jiang A, et al. Transcriptomic characteristics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):761–70.

Xu J, Xu X, Jiang L, Dua K, Hansbro PM, Liu G. SARS-CoV-2 induces transcriptional signatures in human lung epithelial cells that promote lung fibrosis. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):182.

Sun P, Qie S, Liu Z, Ren J, Li K, Xi J. Clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a single arm meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):612–7.

Hanff TC, Harhay MO, Brown TS, Cohen JB, Mohareb AM. Is there an association between COVID-19 mortality and the renin-angiotensin system? A call for epidemiologic investigations. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):870–4.

Li G, He X, Zhang L, Ran Q, Wang J, Xiong A, et al. Assessing ACE2 expression patterns in lung tissues in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. J Autoimmun. 2020;112:102463.

Kai H, Kai M. Interactions of coronaviruses with ACE2, angiotensin II, and RAS inhibitors-lessons from available evidence and insights into COVID-19. Hypertens Res. 2020;43(7):648–54.

Sriram K, Insel PA. A hypothesis for pathobiology and treatment of COVID-19: the centrality of ACE1/ACE2 imbalance. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(21):4825–44.

Uckun FM, Hwang L, Trieu V. Selectively targeting TGF-β with Trabedersen/OT-101 in treatment of evolving and mild ADRS in COVID-19. Clin Invest. 2020;10(2):167–176.

Zhao X, Nicholls JM, Chen YG. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus nucleocapsid protein interacts with Smad3 and modulates transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(6):3272–80.

Chatterjee S. Understanding the nature of variations in structural sequences coding for coronavirus spike, envelope, membrane and nucleocapsid proteins of SARS-CoV-2. Envelope, Membrane and Nucleocapsid Proteins of SARS-CoV-2. 2020.

Hamacher J, Hadizamani Y, Borgmann M, Mohaupt M, Männel DN, Moehrlen U, et al. Cytokine–ion channel interactions in pulmonary inflammation. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1644.

Vadász I, Lucas R. Editorial: cytokine–ion channel interactions in pulmonary inflammation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2598.

Shi M, Zhu J, Wang R, Chen X, Mi L, Walz T, et al. Latent TGF-β structure and activation. Nature. 2011;474(7351):343–9.

Jenkins G. The role of proteases in transforming growth factor-beta activation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(6–7):1068–78.

Liu RM, Desai LP. Reciprocal regulation of TGF-β and reactive oxygen species: a perverse cycle for fibrosis. Redox Biol. 2015;1(6):565–77.

Liu RM, Gaston Pravia KA. Oxidative stress and glutathione in TGF-beta-mediated fibrogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48(1):1–15.

Yokoyama H, Masaki T, Inoue I, Nakamura M, Mezaki Y, Saeki C, et al. Histological and biochemical evaluation of transforming growth factor-β activation and its clinical significance in patients with chronic liver disease. Heliyon. 2019;5(2):e01231.

Ghatak S, Hascall VC, Markwald RR, Feghali-Bostwick C, Artlett CM, Gooz M, et al. Transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1)-induced CD44V6-NOX4 signaling in pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(25):10490–519.

Song HI, Yoon MS. PLD1 regulates adipogenic differentiation through mTOR - IRS-1 phosphorylation at serine 636/639. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36968.

Shulga YV, Anderson RA, Topham MK, Epand RM. Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase isoforms exhibit acyl chain selectivity for both substrate and lipid activator. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(43):35953–63.

Richter K, Kietzmann T. Reactive oxygen species and fibrosis: further evidence of a significant liaison. Cell Tissue Res. 2016;365(3):591–605.

Cheng Y, Zhou M, Zhou W. MicroRNA-30e regulates TGF-β-mediated NADPH oxidase 4-dependent oxidative stress by Snai1 in atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Med. 2019;43(4):1806–16.

Dass E. Brief review of N-acetylcysteine as antiviral agent: potential application in COVID-19. J Biomed Pharm Res. 2020;9(3):69–73.

Forman HJ, Zhang H, Rinna A. Glutathione: overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30(1–2):1–12.

Gaucher C, Boudier A, Bonetti J, Clarot I, Leroy P, Parent M. Glutathione: antioxidant properties dedicated to nanotechnologies. Antioxidants (Basel). 2018;7(5):62.

Pacht ER, Timerman AP, Lykens MG, Merola AJ. Deficiency of alveolar fluid glutathione in patients with sepsis and the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Chest. 1991;100(5):1397–403.

Gould NS, Day BJ. Targeting maladaptive glutathione responses in lung disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81(2):187–93.

Derouiche S. Oxidative stress associated with SARS-Cov-2 (COVID-19) increases the severity of the lung disease-a systematic review. J Infect Dis Epidemiol. 2020;6:121.

Prousky J. The treatment of pulmonary diseases and respiratory-related conditions with inhaled (nebulized or aerosolized) glutathione. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2008;5(1):27–35.

Horowitz RI, Freeman PR, Bruzzese J. Efficacy of glutathione therapy in relieving dyspnea associated with COVID-19 pneumonia: a report of 2 cases. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020;30:101063.

Dietz W, Santos-Burgoa C. Obesity and its implications for COVID-19 mortality. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28(6):1005.

Marí M, Colell A, Morales A, von Montfort C, Garcia-Ruiz C, Fernández-Checa JC. Redox control of liver function in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12(11):1295–331.

Arsalane K, Dubois CM, Muanza T, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 is a potent inhibitor of glutathione synthesis in the lung epithelial cell line A549: transcriptional effect on the GSH rate-limiting enzyme gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17(5):599–607.

Masella R, Mazza G. Glutathione and sulfur amino acids in human health and disease. Hoboken: Wiley; 2009.

Ricard JD, Dreyfuss D, Saumon G. Interaction of VILI with previous lung alterations. In: Ventilator-induced lung injury, vol. 215. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2006. p. 293–314.

Hollenhorst MI, Richter K, Fronius M. Ion transport by pulmonary epithelia. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:174306.

Li X, Vargas Buonfiglio LG, Adam RJ, Stoltz DA, Zabner J, Comellas AP. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator potentiation as a therapeutic strategy for pulmonary edema: a proof-of-concept study in pigs. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(12):e1240–6.

Fang X, Fukuda N, Barbry P, Sartori C, Verkman AS, Matthay MA. Novel role for CFTR in fluid absorption from the distal airspaces of the lung. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119(2):199–207.

Fang X, Song Y, Hirsch J, Galietta LJ, Pedemonte N, Zemans RL, et al. Contribution of CFTR to apical-basolateral fluid transport in cultured human alveolar epithelial type II cells [published correction appears in Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006 May;290(5):L1044]. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290(2):242–9.

Matthay MA, editor. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2003.

Matthay MA. Resolution of pulmonary edema. Thirty years of progress. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(11):1301–8.

Tang L, Fatehi M, Linsdell P. Mechanism of direct bicarbonate transport by the CFTR anion channel. J Cyst Fibros. 2009;8(2):115–21.

Zsembery Á, Kádár K, Jaikumpun P, Deli M, Jakab F, Dobay O. Bicarbonate: an ancient concept to defeat pathogens in light of recent findings beneficial for COVID-19 patients? SSRN J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3589403.

Borowitz D. CFTR, bicarbonate, and the pathophysiology of cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50(Suppl 40):S24–30.

Street ME. HMGB1: a possible crucial therapeutic target for COVID-19? Horm Res Paediatr. 2020;93(2):73–5.

Erfinanda L, Lin Z, Gutbier B, Reppe K, Lienau J, Hocke A, Liedtke W, Witzenrath M, Kuebler WM. Loss of CFTR causes endothelial barrier failure in pneumonia via inhibition of WNK1 and TRPV4 activation. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(61).

Peng JB, Warnock DG. WNK4-mediated regulation of renal ion transport proteins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293(4):F961–73.

Howe KL, Wang A, Hunter MM, Stanton BA, McKay DM. TGFbeta downregulation of the CFTR: a means to limit epithelial chloride secretion. Exp Cell Res. 2004;298(2):473–84.

Shekarabi M, Zhang J, Khanna AR, Ellison DH, Delpire E, Kahle KT. WNK kinase signaling in ion homeostasis and human disease. Cell Metab. 2017;25(2):285–99.

Rosenbaum T, Benítez-Angeles M, Sánchez-Hernández R, Morales-Lázaro SL, Hiriart M, Morales-Buenrostro LE, et al. TRPV4: a physio and pathophysiologically significant ion channel. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113837.

Kuebler WM, Jordt SE, Liedtke WB. Urgent reconsideration of lung edema as a preventable outcome in COVID-19: inhibition of TRPV4 represents a promising and feasible approach. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020;318(6):L1239–43.

Soejima K, Traber LD, Schmalstieg FC, Hawkins H, Jodoin JM, Szabo C, et al. Role of nitric oxide in vascular permeability after combined burns and smoke inhalation injury [published correction appears in Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001 Sep;164(5):909. Varig L [corrected to Virag L]]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(3 Pt 1):745–52.

Cruz DF, Mitash N, Farinha CM, Swiatecka-Urban A. TGF-β1 augments the apical membrane abundance of lemur tyrosine kinase 2 to inhibit CFTR-mediated chloride transport in human bronchial epithelia. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:58.

Lutful Kabir F, Ambalavanan N, Liu G, Li P, Solomon GM, Lal CV, et al. MicroRNA-145 antagonism reverses TGF-β inhibition of F508del CFTR correction in airway epithelia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(5):632–43.

Gillen AE, Gosalia N, Leir SH, Harris A. MicroRNA regulation of expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. Biochem J. 2011;438(1):25–32.

Fabbri E, Tamanini A, Jakova T, Gasparello J, Manicardi A, Corradini R, et al. A peptide nucleic acid against MicroRNA miR-145-5p enhances the expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) in Calu-3 cells. Molecules. 2017;23(1):71.

Mitash N, Donovan JE, Swiatecka-Urban A. The role of microRNA in the airway surface liquid homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):3848.

Yang S, Cui H, Xie N, et al. miR-145 regulates myofibroblast differentiation and lung fibrosis. FASEB J. 2013;27(6):2382–91.

Wei P, Xie Y, Abel PW, et al. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1-induced miR-133a inhibits myofibroblast differentiation and pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(9):670.

Whyte CS, Morrow GB, Mitchell JL, Chowdary P, Mutch NJ. Fibrinolytic abnormalities in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and versatility of thrombolytic drugs to treat COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1548–55.

Ju W, Zhihong Y, Zhiyou Z, Qin H, Dingding W, Li S, et al. Inhibition of α-SMA by the ectodomain of FGFR2c attenuates lung fibrosis. Mol Med. 2012;18(1):992–1002.

Rajasekaran S, Rajaguru P, Sudhakar Gandhi PS. MicroRNAs as potential targets for progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:254.

Davis-Dusenbery BN, Chan MC, Reno KE, Weisman AS, Layne MD, Lagna G, et al. downregulation of Kruppel-like factor-4 (KLF4) by microRNA-143/145 is critical for modulation of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype by transforming growth factor-beta and bone morphogenetic protein 4. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(32):28097–110.

Yeh YT, Wei J, Thorossian S, Nguyen K, Hoffman C, Del Álamo JC, et al. MiR-145 mediates cell morphology-regulated mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to smooth muscle cells. Biomaterials. 2019;204:59–69.

Xu T, Wu YX, Sun JX, Wang FC, Cui ZQ, Xu XH. The role of miR-145 in promoting the fibrosis of pulmonary fibroblasts. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2019;33(5):1337–45.

Megiorni F, Cialfi S, Cimino G, et al. Elevated levels of miR-145 correlate with SMAD3 downregulation in cystic fibrosis patients. J Cyst Fibros. 2013;12(6):797–802.

Tjärnlund-Wolf A, Brogren H, Lo EH, Wang X. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and thrombotic cerebrovascular diseases. Stroke. 2012;43(10):2833–9.

Peng S, Xue G, Gong L, Fang C, Chen J, Yuan C, et al. A long-acting PAI-1 inhibitor reduces thrombus formation. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(7):1338–47.

Freeberg MAT, Easa A, Lillis JA, Benoit DSW, van Wijnen AJ, Awad HA. Transcriptomic analysis of cellular pathways in healing flexor tendons of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1/Serpine1) null mice. J Orthop Res. 2020;38(1):43–58.

Thachil J. The versatile heparin in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1020–2.

Huertas A, Montani D, Savale L, Pichon J, Tu L, Parent F, et al. Endothelial cell dysfunction: a major player in SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19)? Eur Respir J. 2020;56(1):2001634.

Goshua G, Pine AB, Meizlish ML, et al. Endotheliopathy in COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: evidence from a single-centre, cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(8):e575–82.

Ahmed S, Zimba O, Gasparyan AY. Thrombosis in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) through the prism of Virchow’s triad. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(9):2529–43.

Shuto T, Xu H, Wang B, Han J, Kai H, Gu XX, et al. Activation of NF-kappa B by nontypeable Hemophilus influenzae is mediated by toll-like receptor 2-TAK1-dependent NIK-IKK alpha /beta-I kappa B alpha and MKK3/6-p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways in epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(15):8774–9.

Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun SC. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2017;2:17023.

Ingraham NE, Lotfi-Emran S, Thielen BK, Techar K, Morris RS, Holtan SG, et al. Immunomodulation in COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):544–6.

Wu H, editor. TNF receptor associated factors (TRAFs). NewYork: Springer Science & Business Media; 2007.

Yamashita M, Fatyol K, Jin C, Wang X, Liu Z, Zhang YE. TRAF6 mediates Smad-independent activation of JNK and p38 by TGF-beta. Mol Cell. 2008;31(6):918–24.

Zhang YE. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19(1):128–39.

Takaesu G, Kishida S, Hiyama A, Yamaguchi K, Shibuya H, Irie K, et al. TAB2, a novel adaptor protein, mediates activation of TAK1 MAPKKK by linking TAK1 to TRAF6 in the IL-1 signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell. 2000;5(4):649–58.

Shi JH, Sun SC. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor regulation of nuclear factor κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1849.

Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kishimoto K, Hiyama A, Inoue J, Cao Z, Matsumoto K. The kinase TAK1 can activate the NIK-I kappaB as well as the MAP kinase cascade in the IL-1 signalling pathway. Nature. 1999;398(6724):252–6.

Israël A. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(3):a000158.

Margaritopoulos GA, Vasarmidi E, Antoniou KM. Pirfenidone in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an evidence-based review of its place in therapy. Core Evid. 2016;11:11–22.

Stahnke T, Kowtharapu BS, Stachs O, Schmitz KP, Wurm J, Wree A, et al. Suppression of TGF-β pathway by pirfenidone decreases extracellular matrix deposition in ocular fibroblasts in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0172592.

Isaka Y. Targeting TGF-β signaling in kidney fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(9):2532.

Janka-Zires M, Almeda-Valdes P, Uribe-Wiechers AC, Juárez-Comboni SC, López-Gutiérrez J, Escobar-Jiménez JJ, et al. Topical administration of pirfenidone increases healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized crossover study. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:7340641.

Burghardt I, Tritschler F, Opitz CA, Frank B, Weller M, Wick W. Pirfenidone inhibits TGF-beta expression in malignant glioma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354(2):542–7.

Pennison M, Pasche B. Targeting transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19(6):579–85.

Basque J, Martel M, Leduc R, Cantin AM. Lysosomotropic drugs inhibit maturation of transforming growth factor-beta. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86(9):606–12.

Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R, Breitkopf K, Dooley S. Roles of TGF-beta in hepatic fibrosis. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d793–807.

Oida T, Weiner HL. Overexpression of TGF-ß 1 gene induces cell surface localized glucose-regulated protein 78-associated latency-associated peptide/TGF-ß. J Immunol. 2010;185(6):3529–35.

Santibanez JF. Transforming growth factor-Beta and urokinase-type plasminogen activator: dangerous partners in tumorigenesis-implications in skin cancer. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:597927.

Banno A, Reddy AT, Lakshmi SP, Reddy RC. PPARs: key regulators of airway inflammation and potential therapeutic targets in asthma. Nucl Receptor Res. 2018;5:101306.

Gutiérrez-Cuevas J, Sandoval-Rodríguez A, Monroy-Ramírez HC, Vazquez-Del Mercado M, Santos-García A, Armendáriz-Borunda J. Prolonged-release pirfenidone prevents obesity-induced cardiac steatosis and fibrosis in a mouse NASH model. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-020-07014-9.

Ciavarella C, Motta I, Valente S, Pasquinelli G. Pharmacological (or synthetic) and nutritional agonists of PPAR-γ as candidates for cytokine storm modulation in COVID-19 disease. Molecules. 2020;25(9):2076.

Carboni E, Carta AR, Carboni E. Can pioglitazone be potentially useful therapeutically in treating patients with COVID-19? Med Hypotheses. 2020;140:109776.

Krönke G, Kadl A, Ikonomu E, Blüml S, Fürnkranz A, Sarembock IJ, et al. Expression of heme oxygenase-1 in human vascular cells is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(6):1276–82.

Cho RL, Lin WN, Wang CY, Yang CC, Hsiao LD, Lin CC, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 induction by rosiglitazone via PKCα/AMPKα/p38 MAPKα/SIRT1/PPARγ pathway suppresses lipopolysaccharide-mediated pulmonary inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;148:222–37.

Araujo JA, Zhang M, Yin F. Heme oxygenase-1, oxidation, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:119.

Wagener FADTG, Pickkers P, Peterson SJ, Immenschuh S, Abraham NG. Targeting the heme-heme oxygenase system to prevent severe complications following COVID-19 infections. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020;9(6):540.

Hooper PL. COVID-19 and heme oxygenase: novel insight into the disease and potential therapies [published correction appears in Cell Stress Chaperones. 2020 Jun 29]. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2020;25(5):707–10.

Taguchi K, Maruyama T, Otagiri M. Use of hemoglobin for delivering exogenous carbon monoxide in medicinal applications. Curr Med Chem. 2020;27(18):2949–63.

Ryter SW, Choi AM. Therapeutic applications of carbon monoxide in lung disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(3):257–62.

Ryter SW, Ma KC, Choi AMK. Carbon monoxide in lung cell physiology and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2018;314(2):C211–27.

Jiang L, Fei D, Gong R, Yang W, Yu W, Pan S, et al. CORM-2 inhibits TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway in LPS-induced acute lung injury. Inflamm Res. 2016;65(11):905–15.

Lv H, Liu Q, Wen Z, Feng H, Deng X, Ci X. Xanthohumol ameliorates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury via induction of AMPK/GSK3β-Nrf2 signal axis. Redox Biol. 2017;12:311–24.

Chen Z, Zhong H, Wei J, Lin S, Zong Z, Gong F, et al. Inhibition of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling leads to increased activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):300.

Conti P, Ronconi G, Caraffa AL, Gallenga CE, Ross R, Frydas I, Kritas SK. Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-6) and lung inflammation by Coronavirus-19 (COVI-19 or SARS-CoV-2): anti-inflammatory strategies. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34(2):1.

Sandoval-Rodriguez A, Monroy-Ramirez HC, Meza-Rios A, Garcia-Bañuelos J, Vera-Cruz J, Gutiérrez-Cuevas J, et al. Pirfenidone is an agonistic ligand for PPARα and improves NASH by activation of SIRT1/LKB1/pAMPK. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4(3):434–49.

Cho HY, Reddy SP, Kleeberger SR. Nrf2 defends the lung from oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(1–2):76–87. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2006.8.76.

Deng H, editor. Nrf2 and its modulation in inflammation. Cham: Springer Nature; 2020.

Zoja C, Benigni A, Remuzzi G. The Nrf2 pathway in the progression of renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(Suppl 1):i19–24.

Liu Y, Lu F, Kang L, Wang Z, Wang Y. Pirfenidone attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice by regulating Nrf2/Bach1 equilibrium. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):63.

Poe FL, Corn J. N-acetylcysteine: a potential therapeutic agent for SARS-CoV-2. Med Hypotheses. 2020;143:109862.

Shi H, Yin D, Bonella F, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of combined pirfenidone and N-acetylcysteine therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):128.

Tzouvelekis A, Eickelberg O, Kaminski N, Bouros D, Aidinis V, editors. Pulmonary fibrosis. Lausanne: Frontiers Media SA; 2019.

Lancaster LH, de Andrade JA, Zibrak JD, Padilla ML, Albera C, Nathan SD, et al. Pirfenidone safety and adverse event management in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26(146):170057.

Chung MP, Park MS, Oh IJ, Lee HB, Kim YW, Park JS, et al. Safety and efficacy of pirfenidone in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a nationwide post-marketing surveillance study in Korean patients. Adv Ther. 2020;37(5):2303–16.

Xaubet A, Molina-Molina M, Acosta O, Bollo E, Castillo D, Fernández-Fabrellas E, et al. Guidelines for the medical treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [published correction appears in Arch Bronconeumol. 2017 Nov;53(11):657–658]. Normativa sobre el tratamiento farmacológico de la fibrosis pulmonar idiopática [published correction appears in Arch Bronconeumol. 2017 Nov;53(11):657–658]. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53(5):263–269.

Chaudhuri N, Duck A, Frank R, Holme J, Leonard C. Real world experiences: pirfenidone is well tolerated in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med. 2014;108(1):224–6.

Ojo AS, Balogun SA, Williams OT, Ojo OS. Pulmonary fibrosis in COVID-19 survivors: predictive factors and risk reduction strategies. Pulm Med. 2020;2020:6175964.

McDonald LT. Healing after COVID-19: are survivors at risk for pulmonary fibrosis? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2021;320(2):L257–65.

Acknowledgements

Authors are highly grateful to the management of Acharya BM Reddy College of Pharmacy, Bengaluru and Faculty of Pharmacy, MS Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences, Bengaluru for allowing us to carry out our work at their premises.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hamidi, S.H., Kadamboor Veethil, S. & Hamidi, S.H. Role of pirfenidone in TGF-β pathways and other inflammatory pathways in acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a theoretical perspective. Pharmacol. Rep 73, 712–727 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-021-00255-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-021-00255-x