Information seeking behaviors of individuals impacted by COVID-19 international travel restrictions: an analysis of two international cross-sectional studies

- 1School of Population Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Herston, QLD, Australia

- 3Sydney School of Public Health, Faculty of Health and Medicine, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4Independent Researcher, Granada, Spain

Access to accurate information during a crisis is essential. However, while the amount of information circulating during the COVID-19 pandemic has increased exponentially, finding trustworthy resources has been difficult for many, including those affected by international travel restrictions. In this study, we examined the information-seeking behaviors of individuals seeking to travel internationally during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also explored perceptions regarding the value of resources in supporting understanding of COVID-19 travel restriction-related information. Two online cross-sectional surveys targeting four groups were conducted. The groups targeted were: (1) citizens and permanent residents stranded abroad; (2) individuals separated from their partners; (3) individuals separated from immediate families; and (4) temporary visa holders unable to migrate or cross international borders. In total, we analyzed 2,417 completed responses, and a further 296 responses where at least 75% of questions were completed. Findings suggest that social media groups (78.4%, 1,924/2,453), specifically Facebook (86.6%, 2,115/2,422) were the most useful or most used information resource for these groups. Some significant information seeking behavior differences across age and gender were also found. Our study highlights the diversity in information needs of people impacted by COVID-19 travel restrictions and the range of preferred channels through which information is sought. Further, it highlights which challenges hold legitimacy in their target audiences' eyes and which do not. Policymakers may use these results to help formulate more nuanced, consumer-tailored—and hence likely more acceptable, trusted, and impactful—communication strategies as part of future public health emergencies.

Introduction

Citizens stranded abroad, temporary visa holders, and those unable to cross borders to reunite with partners and families have endured a disproportionate burden of COVID-19-related travel restrictions internationally (Ali et al., 2022; Mcdermid et al., 2022a,c). Key findings from recent research highlight the possible psychological and financial impacts incurred by those restricted from traveling internationally, with most respondents reporting a lack of access to government assistance (Mcdermid et al., 2022a,c). Furthermore, a review of government content online for eleven countries found that information for those stranded abroad during the COVID-19 pandemic was inadequate and—for the most part—difficult to understand (Mcdermid et al., 2022b). This research recommended that governments explore ways to better meet the information needs of vulnerable citizens stranded abroad during the COVID-19 crisis, and should be better prepared for future public health emergencies.

Effective communication during a public health emergency requires that information is not only readily available to the people that need it, but that the information is in a format that is understandable, action-oriented, and supports understanding (Ali et al., 2020; Chu et al., 2021; Ferguson et al., 2021). Information seeking during the COVID-19 pandemic increased drastically, and was, in part, led by the high levels of uncertainty, fear, anxiety and irrational public behaviors (Lin et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2023). With the plethora of information being delivered daily during the pandemic, it is vital that information is delivered in an appropriate manner to the audience and considers the increasing risks of misinformation (and disinformation). Currently, there is limited evidence on the information seeking behaviors of travelers, and those directly impacted by travel restrictions during the pandemic.

There is growing evidence to suggest an increasing reliance and trust in social media as a source of information during emergency events, with decreasing confidence in traditional government-delivered details (Ali et al., 2020; Chu et al., 2021). Understanding the complex reasons behind these changes in consumer sentiment and preference are essential for pandemic preparedness and response efforts, particularly to inform how public health risk messages and communication may be disseminated to the best effect during heightened anxiety and information need (Suarez-Lledo and Alvarez-Galvez, 2021). Although social media is a fast and effective communication method, concerns about misinformation (and dis-information) have been raised (Suarez-Lledo and Alvarez-Galvez, 2021; Al-Zaman, 2022).

At the time of writing, research exploring the experiences of people stranded abroad was still limited, with most research focusing on the impact that travel restrictions had on disease importation (Wells et al., 2020; Bou-Karroum et al., 2021; Liebig et al., 2021).

This paper builds on our previous work, and aimed to fill the gap of evidence by examining the information seeking behaviors of people impacted by international travel restrictions, including citizens and permanent residents, those separated from their partner, those separated from their immediate families and temporary visa holders. We aimed to (1) identify the sources of information, and the perceived usefulness of COVID-19 specific information, and (2) identify demographic factors associated with certain information seeking behaviors.

Materials and methods

Data collection

We conducted two online international cross-sectional surveys targeting four groups of people affected by COVID-19 international travel restrictions globally. The groups were (1) citizens and permanent residents stranded abroad in the first survey, and following feedback from individuals not eligible to participate in the first survey, the second survey included three groups including (2) individuals separated from their partners; (3) individuals separated from their immediate families; and (4) temporary visa holders unable to migrate or cross international borders. These groups will henceforth be referred to as “stranded or/and separated.”

The first survey was designed to collect data on the psychological and financial impact of COVID-19 travel restrictions on citizens or permanent residents stranded abroad (Mcdermid et al., 2022a). Data collected included demographics, travel experiences, mental wellbeing (using the validated DASS-21 tool), information-seeking behaviors, and financial well-being. The survey was administered from July 20 and September 24, 2021. The second survey had a similar design to collect data on the psychological and financial impact of COVID-19 travel restrictions (Mcdermid et al., 2022c). Most of the questions were the same, and included the validated tools to assess psychological distress, the financial distress, demographic characteristics. Travel related behavioral questions were relevant to the eligible groups in the second survey, and based on feedback from the first survey we included questions about access to psychological support and additional questions relating to misinformation within information sources. It was administered from November 4 to December 1, 2021.

To address the aims of this paper, we analyzed outputs not previously investigated in the first two publications, specific to information seeking behaviors and perceived usefulness of the information sources for the four groups identified, to provide a more substantial picture of the needs of those unable to travel due to international travel restrictions. Similar questions were administered across both surveys, with identical questions asked about the best way for governments to send information in the future and what social media participants used the most or were the most useful. Key differences were in the additional response options and a question on misinformation in the second survey. We also removed questions more relevant to the first survey population from the second survey.

To be eligible, participants had to meet the following criteria: were impacted due to COVID-19-related travel restrictions and specifically experienced still being stranded or at some point had been stranded from their country or residence/home or; physical separation from a partner; physical separation from immediate families or; temporary visa holders unable to migrate. There were no geographical based exclusion criteria. Both surveys were created and administered using the Qualtrics (2005) survey platform. Participants were recruited through a variety of social media channels, including twitter, online blogs, and Facebook including targeted Facebook groups with names related to “travel or border restrictions,” being “stranded,” or “stuck overseas/abroad.” For the second survey, a link was emailed to a list of impacted individuals who opted in to being contacted about research opportunities from a grassroots advocacy group, targeted to those impacted by the Australian border restrictions. Participants' anonymity was maintained.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and inferential analyses were performed on quantitative data using SPSS (2021). Multiple chi-square tests for association were conducted to assess the associations between the demographic factors of age and gender on the perceived usefulness of information sources, and the method by which participants feel that government should send information in the future. Age was categorized in groups 18–29, 30–49, 50–69, and 70+. Where cell counts in the cross-tabulation were <5, a Fisher's exact test was used. We determined a significant result with a p-value < 0.05.

Ethics

Ethical approval for this body of work was granted by the UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee (#210418). All participants indicated their consent to participate.

Results

In total, across the two surveys, there were 2,417 completed responses, with a further 296 responses where respondents had completed at least 75% of the questions in the first survey. Within the initial survey, a total of 1,054 people completed the survey, with a further 296 responses who completed over 75% of the questions and were included in the descriptive analysis. Most of those who completed the initial survey (69.5%, 733/1,054) were female, had tertiary education (90.7%, 956/1,054), and identified as having North-West European ethnicity (43.8%, 462/1,054). The mean age of respondents was 41.09 (SD = 13.08). Most participants were stranded in the European Region (45.3%, 608/1,341) and trying to return to the Western Pacific Region (75.4%, 1,011/1,341).

Within the second survey, a total of 1,363 participants completed the survey (only completed surveys were analyzed, incomplete surveys were treated as missing completely at random), with most participants being female (73.5%, 1,002/1,363), with tertiary education (91.9%, 1,253/1,363), and a mean age of 36.7 (SD = 11.21). Participants identified as either being separated from their immediate family (50.6%, 690/1,363), separated from their partner/spouse (31.3%, 427/1,363) or temporary visa holders unable to migrate (18%, 246/1,363). For those who were separated, most were stranded in the Western Pacific Region (50.9%, 569/1,117) with their families/partners located in the Western Pacific Region (38%, 424/1,117) or the European Region (29.5%, 330/1,117). For temporary visa holders, many were waiting in the South East Asian Region (42.3%, 104/246), trying to enter the Western Pacific Region (87.8%, 216/246).

Information seeking behaviors

The majority (85.2%, 1,150/1,350) of citizens or permanent residents stranded abroad spent up to 3 h seeking information to help them, with 78.7% (833/1,059) reporting moderate-to-extreme difficulty in finding accurate and understandable information about changes to travel plans. See Table 1 for a full breakdown of participant responses. Most respondents found government advice extremely difficult to understand (30.9%, 326/1,059) and were dissatisfied with the amount of information provided by their government (73.4%, 778/1,059).

Table 1. Information seeking behaviors of citizens and permanent residents stranded abroad during COVID-19 travel restrictions.

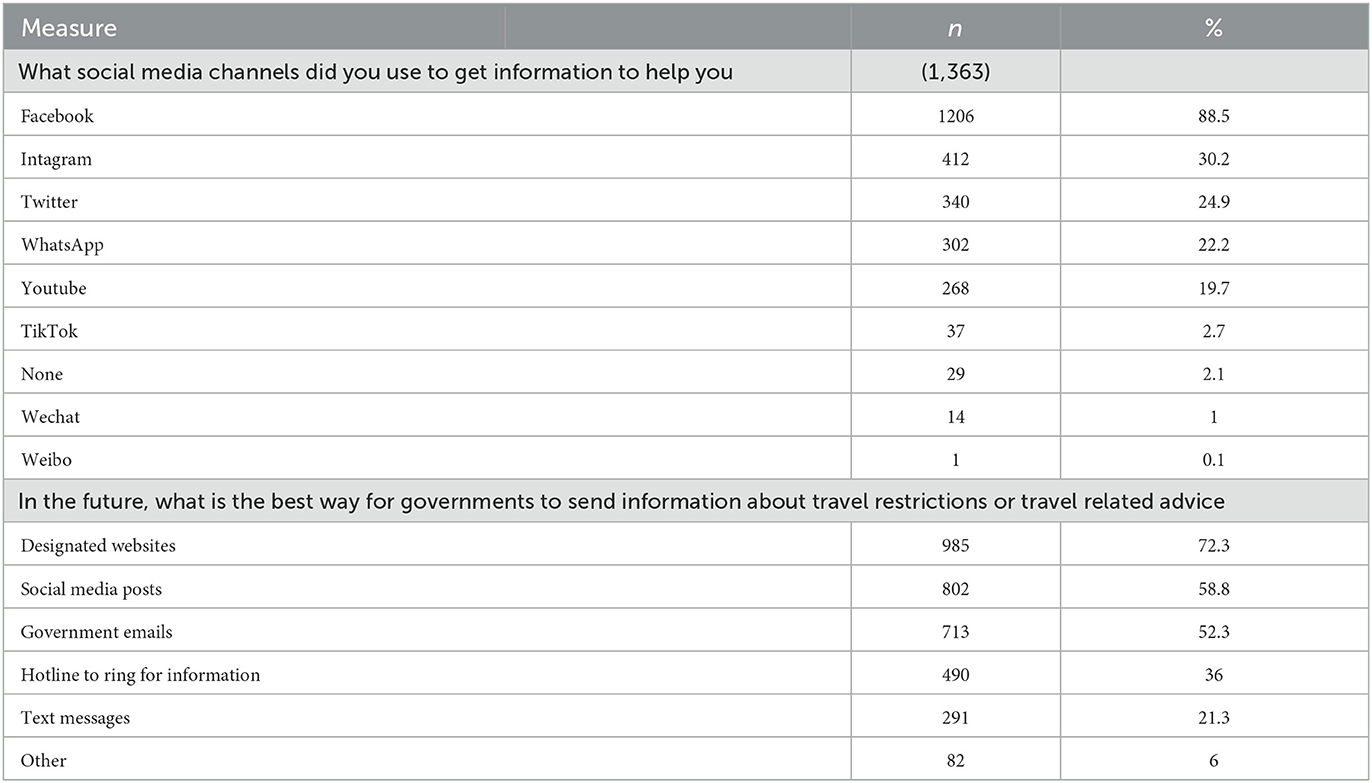

For citizens or permanent residents stranded abroad, most reported designated websites (64.3%, 678/1,054) or government emails (53.4%, 563/1,054) as the best way for governments to send information regarding travel restrictions in the future. For those separated from their family/partner and temporary visa holders unable to migrate, most reported social media posts (58.8%, 802/1,363) or designated websites (72.3, 985/1,363) as the best way for governments to send information regarding travel restrictions in the future (see Table 2).

Table 2. Information seeking behaviors of individuals separated from their partner or immediate family and temporary visa holders unable to immigrate or cross international borders during COVID-19 travel restrictions.

Perceived usefulness of COVID-related information

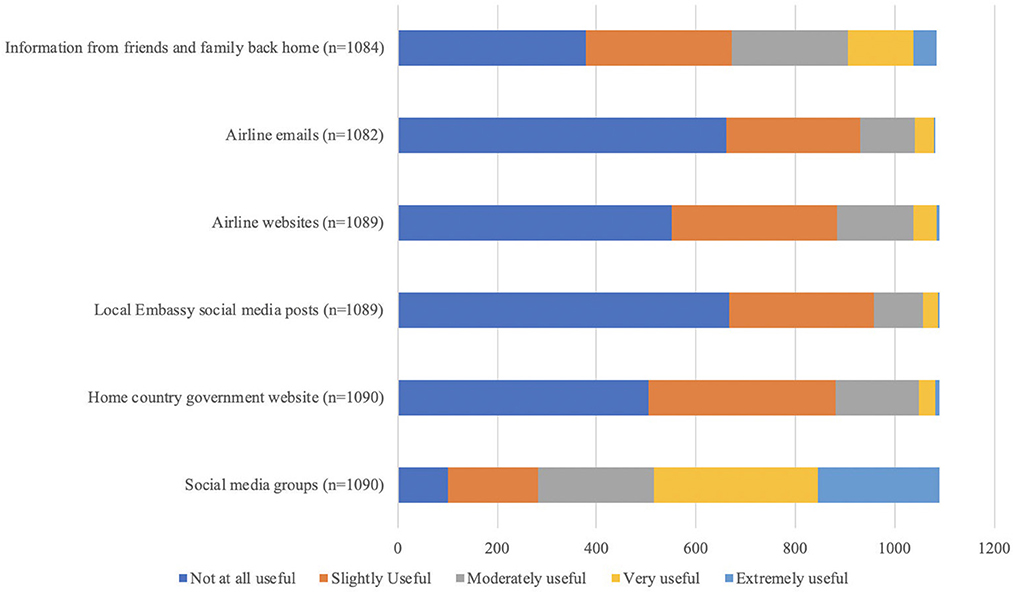

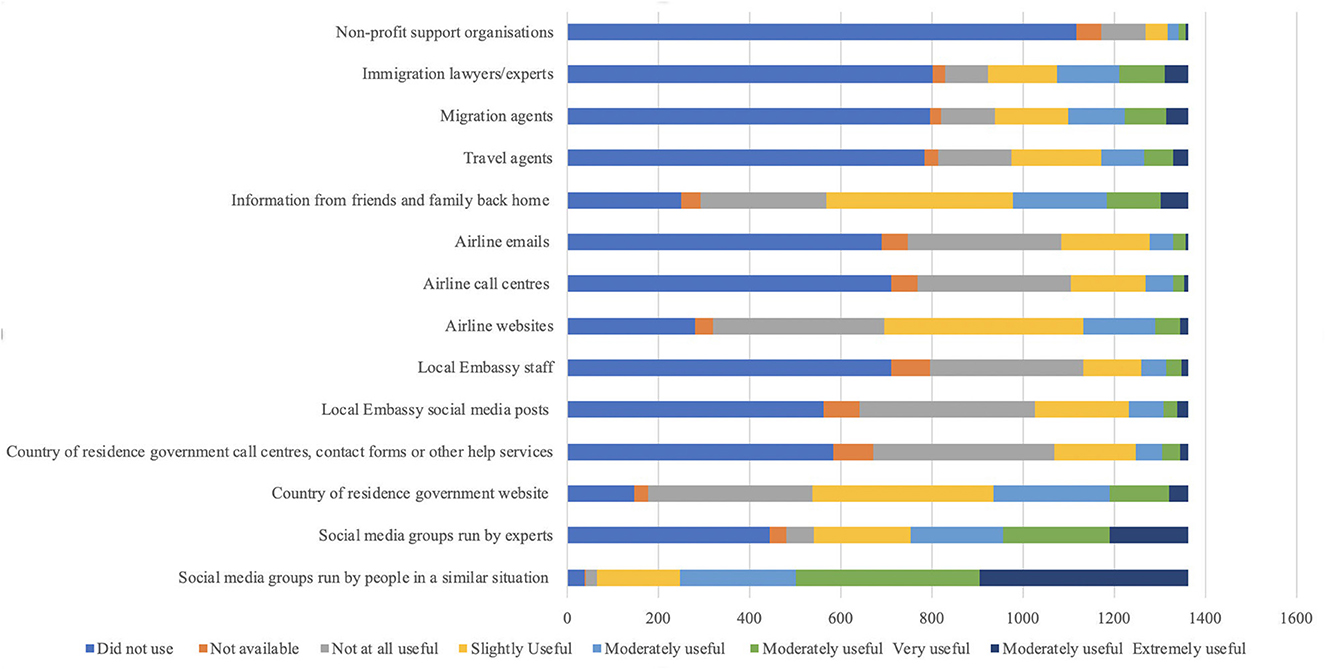

Regarding the sources available in supporting those stranded or separated in both surveys, social media groups were the most useful, with 78.4% (1,924/2,453) reporting that social media groups were moderate to extremely useful compared to the other sources. Local embassy social media posts were reported as the least useful for citizens or permanent residents (12%, 130/1,089), compared to 55% of respondents separated from family/partners or temporary visa holders reporting government websites being the least useful (reporting slightly or not at all useful, 757/1,363). See Figures 1, 2 for a full breakdown of participant responses.

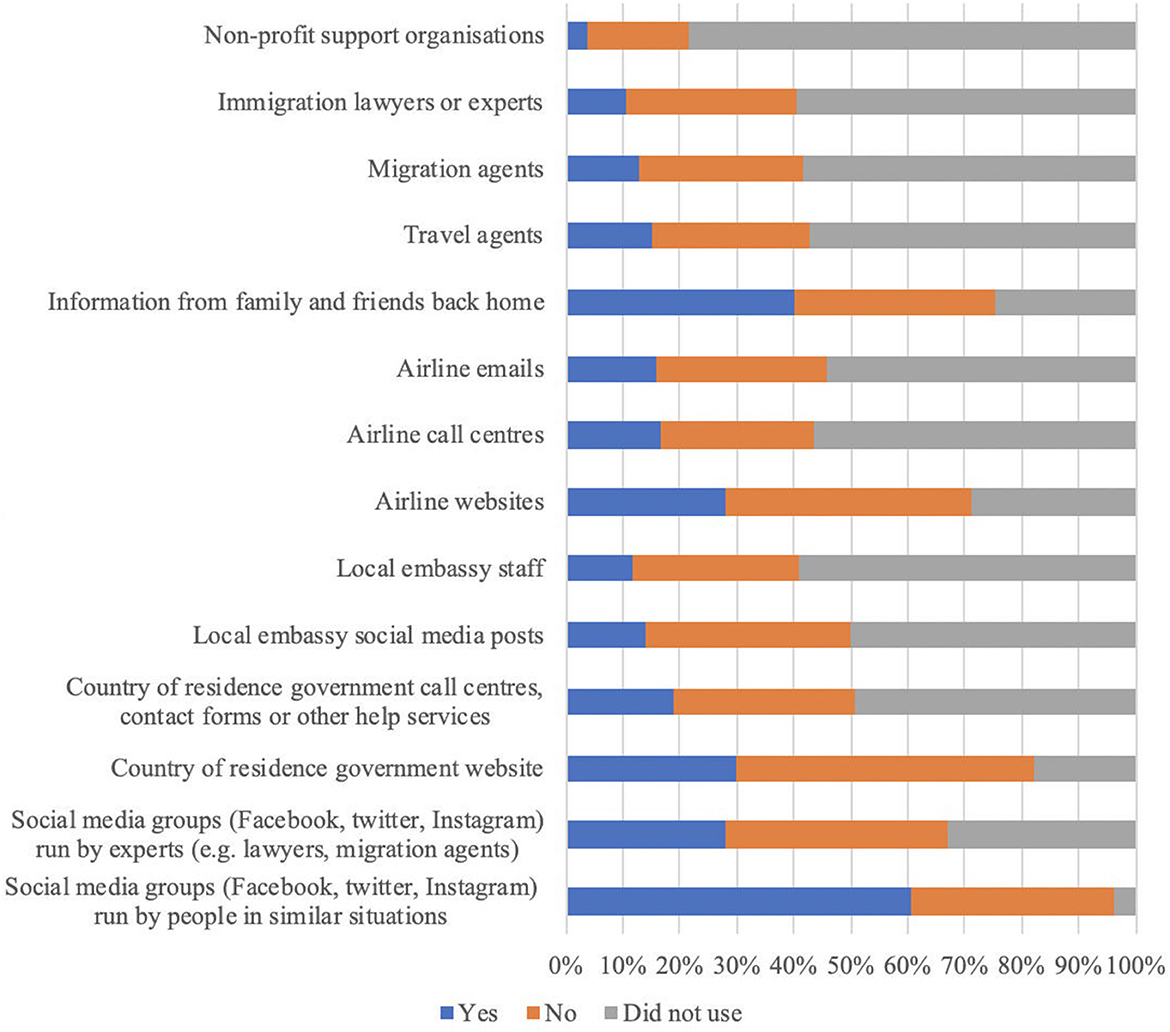

When comparing participants use of social media in finding information, Facebook was reported as the most useful social media channel (Survey 1) and the most used (Survey 2) by participants (86.6%, 2,115/2,422). Of note, respondents separated from family/partners or temporary visa holders in the second survey reported multiple cases of finding inaccurate or misleading information regarding travel restrictions or travel-related advice (Figure 3), most frequently written in social media groups run by people in a similar situation (60.6%, 826/1,363), information from family and friends (40.1%, 547/1,363) and government websites (29.8%, 406/1,363).

Figure 3. Percentage of participants who were separated or temporary visa holders reporting inaccurate or misleading information regarding travel restriction or travel related advice (n = 1,363).

Analysis of demographic characteristics and information-seeking behaviors

Chi squared tests for association were used to compare age and gender to information-seeking behaviors of citizens or permanent residents stranded abroad. Results are displayed in Supplementary Table 1. Statistically significant differences were found between gender and the perceived usefulness of social media (p = 0.005), with women finding social media more useful than men. Gender differences were also found regarding the perceived usefulness of information provided by friends and family (p = 0.002), with men finding this information more useful than women. For age, there were statistically significant differences in the perceived usefulness of airline emails (p = 0.016) and information provided by friends and family (p = 0.011), with those aged 50–60 finding airline emails less useful compared to other age groups, and participants aged 30–49 finding information provided by family and friends to be least useful.

Chi squared association tests were used to compare age and gender to information-seeking behaviors for those separated from their family/partner and temporary visa holders unable to migrate. Results are displayed in Supplementary Table 2. Statistically significant differences were found between gender and (1) the best way governments could send information in the future (p < 0.001), with women finding social media posts and a hotline more useful than men; (2) the perceived usefulness of social media groups run by people in similar situations (p = 0.005), with women finding it more useful; (3) social media groups run by experts (p < 0.001), with women finding it more useful; (4) the information provided by friends and family (p = 0.038), with men finding it more useful and; (5) migration agents (p = 0.045), with men finding it more useful.

For age, there were statistically significant differences in (1) the best way governments could send information in the future (p = 0.010), with those 70+ preferring government emails, compared to the other age groups preferring a designated website or social media posts; (2) the perceived usefulness of airline websites (p = 0.024), with those 70+ finding it the more useful than other groups; (3) airline call centers (p = 0.004), with those aged 50–69 finding it the more useful; (4) the information provided by friends and family (p = 0.003), with participants aged 70+ finding it the more useful than other groups; (5) travel agents (p = 0.041), with those aged 70+ finding it less useful and; (6) not-for-profit organizations (p = 0.009), where 30–49 year old participants finding it more useful than other groups.

Discussion

In this study, we present previously investigated data from two surveys representing a total of 1,350 participants from the first and 1,363 from the second, with all respondents being those who were directly affected by COVID-19 related international travel restrictions. The study evaluated the information seeking behaviors and the perceived usefulness of information sources of individuals impacted by international travel restrictions. Results from the first survey, distributed in late 2021, reflect the ongoing increased demand for accurate information during COVID-19, with 71% of respondents reporting spending more than 1 h daily seeking information to support them while stranded abroad. A concerning 79% finding it moderately-to-extremely difficult to source accurate and understandable information regarding travel restrictions. These results are perhaps unsurprising considering the anxiety and stress related to the pandemic, and the influx of health information seeking during COVID-19, reported in populations globally (Lin et al., 2016; Skarpa and Garoufallou, 2021; Soleymani et al., 2021; Soroya et al., 2021). Similarly, for participants in a survey study conducted in Greece in early 2020, spent up to 2 h daily seeking information specific to COVID-19, and although sourcing information through multiple channels, participants paid attention to official sources of information (Skarpa and Garoufallou, 2021).

We found that for all respondents, a range of communication channels was utilized for information gathering. However, social media groups were cited as being the most useful source of finding information on travel restrictions (78.4%, 1,924/2,453) and comparatively, government sources, including websites, call centers and embassy social media posts, were reported as being some of the least useful. These results are consistent with the many studies reporting that individuals, especially during pandemics, report getting information through multiple channels (Fitzpatrick-Lewis et al., 2010; Berg et al., 2021; Skarpa and Garoufallou, 2021; Soleymani et al., 2021). A potential issue with this comes in the form of information overload, which can influence an individual's mental wellbeing (Baerg and Bruchmann, 2022; Mohammed et al., 2022).

Social media presents a great way to communicate during a rapidly changing environment and is especially relevant to reaching international audiences. Our results show that 87% of respondents across both surveys reported Facebook as the most useful social media platform for sourcing information, suggesting that this platform could be the most influential for governments to disseminate information on travel restrictions. For example, New Zealand, who responded rapidly to the COVID-19 pandemic (Beattie and Priestley, 2021), introduced a two-way communication strategy and utilized Facebook as a way in which citizens can find transparent, accurate information, with the Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern introducing live chats on Facebook for people to be able to ask questions in real-time (Gesser-Edelsburg, 2021).

The evident shift toward social media in seeking information during the COVID-19 pandemic as opposed to more traditional sources, like publicly funded news channels, news articles or government publications, provides individuals with fast access to updated information to keep informed; however, this comes with additional problems (Cinelli et al., 2020). Specifically, the spread of health-related misinformation, which had a very real and lasting impact on undermining the public health effort (Moscadelli et al., 2020), and was amplified on social media and other online platforms (Bridgman et al., 2021; WHO, 2021). Results from our second survey reflect the prevalence of misinformation online during COVID-19 and found that 60.6% of respondents reported inaccurate or misleading information within social media groups. The rates of misleading or erroneous information on government platforms were higher than expected, with 29.8% reporting on government websites, 10.1% through government call centers or help services, 14.1% on local embassy social media posts and 11.9% from local embassy staff themselves. This result, coupled with the analysis of government information highlighting both an overall lack of information and poor readability, paint a concerning picture of the state of government communication and overall support during a time where information seeking is at a peak and being consumed daily (Mcdermid et al., 2022b). Considering most participants in both surveys within this study (68.8%, 1,663/2,417) would prefer a dedicated website as the best way for governments to send information in the future, these are important deficiencies that need to be addressed.

Consistent with previous research, we found that information seeking behavior specific to international travel restrictions varied significantly by age and gender (Figueiras et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2021). For all separated and stranded groups, women found information sourced through social media more useful, and information provided by friends and family less useful than men did. Age was also associated with the perceived usefulness of sources in both surveys, specifically with airline emails and information provided by friends and family for citizens abroad, and for those separated from their partner or family and temporary visa holders, differences were found in age across the perceived usefulness of airline websites and call centers, along with information provided by friends and family, travel agents, and not-for-profit organizations.

Regarding the recommended source for governments to disseminate information about travel restrictions, citizens and permanent residents stranded abroad differed significantly based on age but not gender. For those aged 50 and above, a designated website was the most frequently recommended, whereas for participants aged under 50 years, social media, government emails and a dedicated webpage were commonly recommended. For participants separated from their partners or immediate family and temporary visa holders, differences in recommended sources of government information were found across both age and gender. Women recommended social media posts, designated websites, and hotlines more than men. Those under 50 more frequently recommended designated websites, government emails and social media posts. These results are not the first in highlighting the gender and age differences in online information seeking and social media and technology use during the COVID-19 pandemic (Chidiac et al., 2022; Li and Zheng, 2022), but provide much needed evidence for information seeking behaviors and preferences directly relating to people who are unable to cross borders. This may be important information in future public health emergencies where governments need to communicate with citizens, residents, and their families outside of the country in a timely manner.

Coupled with our previous results showing poor readability, usability, and accessibility on COVID-19 related information available on four countries' websites (Mcdermid et al., 2022b), the current study highlights the varied needs of the many people impacted by travel restrictions. These groups require updated, reliable, and trustworthy information, especially from governments, due to the constantly changing environment of travel restrictions likely to continue in future public health crises. As this data was collected at the end of 2021, more than 20 months into the pandemic, this is an ongoing concern that needs the attention of policymakers.

A one size fits all approach will not work in this case, as we found statistically significant differences in information-seeking behavior for age and gender, and for this reason, we recommend policymakers consider integrating multiple channels for disseminating information, incorporating the needs of this target group. Second to this recommendation is in making the information given more readable, accessible, and usable. Finally, we recommend introducing methods and policies to combat misinformation and decreased trust in government, focusing on the government actions identified by Pomeranz and Schwid (2021) of disseminating accurate information, supporting an independent media environment and protecting expression.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, as both surveys were disseminated online, primarily through social media, with participant being self-selected, our sample has a high representation of those with tertiary education, and females, showing limited representativeness of the population. Secondly, our results are unlikely to consider the experiences and needs of individuals with low technological literacy or issues with geographical or financial access to technology. Third, an important factor that could impact information seeking behavior is ethnicity which was not collected in the second survey and was not introduced in the analyses for this study. Further research is recommended to investigate the impact of ethnicity on understanding information and trust in sources. Like with other cross-sectional surveys, our study could not collect longitudinal data but offers a unique snapshot of information behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While further research is needed, these findings are novel and have practical implications which could improve pandemic communication and engagement policies, especially those aimed at individuals impacted by travel restrictions.

Conclusion

This study explored the information seeking behaviors of a large sample of individuals impacted by COVID-19-related international travel restrictions and found that age and gender were significantly associated with perceived usefulness in different information sources and recommendations for future government information dissemination channels. Participants reported not only misinformation in different information channels, but also reported low levels of usefulness across most information channels. These findings provide evidence that will inform how public health emergency communication may be framed and best delivered to targeted high-risk audiences to ensure both their needs and the aims of response agencies are best met. This is especially important when needing to communicate to citizens and residents when they are traveling, working, living, or temporarily abroad during a public health emergency or international crisis.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the UNSW Human Research Ethics Committee (#210418). All respondents indicated their consent to participate.

Author contributions

PM: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. AC: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing. MS: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, writing—review and editing. KB: Formal analysis, writing—review and editing. ST: Investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing. HS: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1101548/full#supplementary-material

References

Ali, K., Iasiello, M., Van Agteren, J., Mavrangelos, T., Kyrios, M., and Fassnacht, D. B. (2022). A cross-sectional investigation of the mental health and wellbeing among individuals who have been negatively impacted by the COVID-19 international border closure in Australia. Global. Health 18, 12. doi: 10.1186/s12992-022-00807-7

Ali, S. H., Foreman, J., Tozan, Y., Capasso, A., Jones, A. M., and Diclemente, R. J. (2020). Trends and predictors of COVID-19 information sources and their relationship with knowledge and beliefs related to the pandemic: nationwide cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 6, e21071–e21071. doi: 10.2196/21071

Al-Zaman, M. S. (2022). Prevalence and source analysis of COVID-19 misinformation in 138 countries. IFLA J. 48, 189–204. doi: 10.1177/03400352211041135

Baerg, L., and Bruchmann, K. (2022). COVID-19 information overload: intolerance of uncertainty moderates the relationship between frequency of internet searching and fear of COVID-19. Acta Psychol. 224, 103534. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103534

Beattie, A., and Priestley, R. (2021). Fighting COVID-19 with the team of 5 million: Aotearoa New Zealand government communication during the 2020 lockdown. Soc. Sci. Humanities Open 4, 100209. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100209

Berg, S. H., O'hara, J. K., Shortt, M. T., Thune, H., Brønnick, K. K., Lungu, D. A., et al. (2021). Health authorities' health risk communication with the public during pandemics: a rapid scoping review. BMC Public Health 21, 1401. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11468-3

Bou-Karroum, L., Khabsa, J., Jabbour, M., Hilal, N., Haidar, Z., Abi Khalil, P., et al. (2021). Public health effects of travel-related policies on the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods systematic review. J. Infect. 83, 413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.07017

Bridgman, A., Merkley, E., Zhilin, O., Loewen, P. J., Owen, T., and Ruths, D. (2021). Infodemic pathways: evaluating the role that traditional and social media play in cross-national information transfer. Front. Polit. Sci. 3. 73. doi: 10.3389./fpos.2021.727073

Chidiac, M., Ross, C., Marston, H. R., and Freeman, S. (2022). Age and gender perspectives on social media and technology practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 3696. doi: 10.3390./ijerph192113969

Chu, L., Fung, H. H., Tse, D. C. K., Tsang, V. H. L., Zhang, H., and Mai, C. (2021). Obtaining information from different sources matters during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontologist 61, 187–195. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa222

Cinelli, M., Quattrociocchi, W., Galeazzi, A., Valensise, C. M., Brugnoli, E., Schmidt, A. L., et al. (2020). The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Sci. Rep. 10, 16598. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5

Ferguson, C., Merga, M., and Winn, S. (2021). Communications in the time of a pandemic: the readability of documents for public consumption. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 45, 116–121. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.13066

Figueiras, M. J., Ghorayeb, J., Coutinho, M. V. C., Marôco, J., and Thomas, J. (2021). Levels of trust in information sources as a predictor of protective health behaviors during COVID-19 pandemic: a UAE cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 12, 550. doi: 10.3389./fpsyg.2021.633550

Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D., Yost, J., Ciliska, D., and Krishnaratne, S. (2010). Communication about environmental health risks: a systematic review. Environ. Health 9, 67. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-9-67

Gesser-Edelsburg, A. (2021). How to make health and risk communication on social media more “social” during COVID-19. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 14, 3523–3540. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S317517

Huang, J., Ren, W., Wang, S., Zhou, Y., and Yang, Y. (2023). Positive emotion and media dependence: measuring risk information seeking and perception in the COVID-19 pandemic prevention. Inquiry 60, 469580231159747. doi: 10.1177/00469580231159747

Li, J., and Zheng, H. (2022). Online information seeking and disease prevention intent during COVID-19 outbreak. J.Mass Commun. Quart. 99, 69–88. doi: 10.1177/1077699020961518

Liebig, J., Najeebullah, K., Jurdak, R., Shoghri, A. E., and Paini, D. (2021). Should international borders re-open? The impact of travel restrictions on COVID-19 importation risk. BMC Public Health 21, 1573. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11616-9

Lin, W-. Y., Zhang, X., Song, H., and Omori, K. (2016). Health information seeking in the Web 2.0 age: trust in social media, uncertainty reduction, and self-disclosure. Comput. Human Behav. 56, 289-294. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.11055

Mcdermid, P., Craig, A., Sheel, M., Blazek, K., Talty, S., and Seale, H. (2022a). Examining the psychological and financial impact of travel restrictions on citizens and permanent residents stranded abroad during the COVID-19 pandemic: international cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 12, e059922. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059922

Mcdermid, P., Craig, A., Sheel, M., and Seale, H. (2022b). How have governments supported citizens stranded abroad due to COVID-19 travel restrictions? A comparative analysis of the financial and health support in eleven countries. BMC Infect. Dis. 22, 161. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07155-2

Mcdermid, P., Sooppiyaragath, S., Craig, A., Sheel, M., Blazek, K., Talty, S., et al. (2022c). Psychological and financial impacts of COVID-19-related travel measures: an international cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 17, e0271894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271894

Mohammed, M. Sha'aban, A., Jatau, A. I., Yunusa, I., Isa, A. M., Wada, A. S., Obamiro, K., et al. (2022). Assessment of COVID-19 information overload among the general public. J. Racial Ethnic Health Disp. 9, 184–192. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00942-0

Moscadelli, A., Albora, G., Biamonte, M. A., Giorgetti, D., Innocenzio, M., Paoli, S., et al. (2020). Fake news and COVID-19 in Italy: results of a quantitative observational study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 5850. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165850

Pomeranz, J. L., and Schwid, A. R. (2021). Governmental actions to address COVID-19 misinformation. J. Public Health Policy 42, 201–210. doi: 10.1057/s41271-020-00270-x

Schmidt, H., d Wild, E-. M., and Schreyögg, J. (2021). Explaining variation in health information seeking behaviour—Insights from a multilingual survey. Health Policy 125, 618–626. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.01008

Skarpa, P. E., and Garoufallou, E. (2021). Information seeking behavior and COVID-19 pandemic: a snapshot of young, middle aged and senior individuals in Greece. Int. J. Med. Inform. 150, 104465. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104465

Soleymani, M. R., Esmaeilzadeh, M., Taghipour, F., and Ashrafi-Rizi, H. (2021). COVID-19 information seeking needs and behaviour among citizens in Isfahan, Iran: a qualitative study. Health Info. Libr. J. 3, 396. doi: 10.1111./hir.12396

Soroya, S. H., Farooq, A., Mahmood, K., Isoaho, J., and Zara, S.-E. (2021). From information seeking to information avoidance: understanding the health information behavior during a global health crisis. Inform. Process. Manag. 58, 102440. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102440

Suarez-Lledo, V., and Alvarez-Galvez, J. (2021). Prevalence of health misinformation on social media: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e17187. doi: 10.2196/17187

Wells, C. R., Sah, P., Moghadas, S. M., Pandey, A., Shoukat, A., Wang, Y., et al. (2020). Impact of international travel and border control measures on the global spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 117, 7504–7509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002616117

Keywords: COVID-19, pandemic, crisis communication, information, public health, misinformation, social media

Citation: McDermid P, Craig A, Sheel M, Blazek K, Talty S and Seale H (2023) Information seeking behaviors of individuals impacted by COVID-19 international travel restrictions: an analysis of two international cross-sectional studies. Front. Commun. 8:1101548. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1101548

Received: 18 November 2022; Accepted: 24 August 2023;

Published: 07 September 2023.

Edited by:

Serena Tagliacozzo, National Research Council (CNR), ItalyReviewed by:

Gisela Gonçalves, University of Beira Interior, PortugalArielle Kaim, Tel Aviv University, Israel

Arej Alhemimah, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2023 McDermid, Craig, Sheel, Blazek, Talty and Seale. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Holly Seale, h.seale@unsw.edu.au

Pippa McDermid

Pippa McDermid Adam Craig2

Adam Craig2  Holly Seale

Holly Seale