Abstract

Objective

To assess health equity-oriented COVID-19 reporting across Canadian provinces and territories, using a scorecard approach.

Methods

A scan was performed of provincial and territorial reporting of five data elements (cumulative totals of tests, cases, hospitalizations, deaths, and population size) across three units of aggregation (province or territory level, health regions, and local areas) (15 “overall” indicators), and for four vulnerable settings (long-term care and detention facilities, schools, and homeless shelters) and eight social markers (age, sex, immigration status, race/ethnicity, healthcare worker status, occupational sector, income, and education) (180 “equity-related” indicators) as of December 31, 2020. Per indicator, one point was awarded if case-delimited data were released, 0.7 points if only summary statistics were reported, and 0 if neither was provided. Results were presented using a scorecard approach.

Results

Overall, information was more complete for cases and deaths than for tests, hospitalizations, and population size denominators needed for rate estimation. Information provided on jurisdictions and their regions, overall, tended to be more available (average score of 58%, “D”) than that for equity-related indicators (average score of 17%, “F”). Only British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario provided case-delimited data, with Ontario and Alberta providing case information for local areas. No jurisdiction reported on outcomes according to patients’ immigration status, race/ethnicity, income, or education. Though several provinces reported on cases in long-term care facilities, only Ontario and Quebec provided detailed information for detention facilities and schools, and only Ontario reported on cases within homeless shelters and across occupational sectors.

Conclusion

One year into the pandemic, socially stratified reporting for COVID-19 outcomes remains sparse in Canada. However, several “best practices” in health equity-oriented reporting were observed and set a relevant precedent for all jurisdictions to follow for this pandemic and future ones.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer les pratiques de déclaration des données de surveillance de la COVID-19 axée sur l’équité en matière de santé dans les provinces et territoires canadiens, en utilisant une fiche de pointage.

Méthodes

Les sites webs et rapports officiels des provinces et territoires ont été analysés pour identifier la présence de cinq éléments de données sur la COVID-19 (totaux cumulatifs des tests, cas, hospitalisations et décès ainsi que la taille de la population évaluée, nécessaire pour l’estimation de taux), déclarées au niveau de trois unités d’agrégation populationnelle (de la province/du territoire, des régions socio-sanitaires, et des localités/quartiers) (15 indicateurs de données « globales »); ainsi qu’au niveau de quatre milieux à risque d’éclosions (les établissements de soins de longue durée et de détention, les écoles, et les refuges pour personnes en situation d’itinérance) et de huit marqueurs sociaux (l’âge, le sexe, le statut d’immigration, la race/ethnicité, le statut de travailleur de santé, le revenu, le niveau d’éducation, et le secteur de travail) (180 indicateurs d’équité en matière de santé) à compter du 31 décembre 2020. Pour chaque indicateur, un point a été attribué si des données délimitées par cas ont été publiées, 0,7 points si seules les statistiques sommaires ont été communiquées, et 0 si aucune information n’a été fournie. Les résultats sont présentés sous la forme d’une fiche de pointage.

Résultats

Dans l’ensemble, les informations sur les cas et les décès étaient plus complètes que celles pour les tests, les hospitalisations et les tailles de population. Les éléments de données étaient plus disponibles au niveau global des provinces et territoires et de leurs régions socio-sanitaires (note moyenne de 58 % ou « D ») que pour les indicateurs liés à l’équité en matière de santé (note moyenne de 17 % ou « F »). Seuls la Colombie-Britannique, l’Alberta et l’Ontario ont fourni des données délimitées par cas, et seuls l’Alberta et l’Ontario ont fourni des données au niveau local. Aucune juridiction n’a fait état de données en fonction du statut d’immigration, de la race/l’ethnicité, du revenu ou du niveau d’éducation des patients. Plusieurs juridictions ont fourni des informations au sujet des cas au sein des établissements de soins de longue durée, mais seuls l’Ontario et le Québec ont fourni des informations détaillées au sujet des établissements de détention et des écoles. L’Ontario était unique en rapportant sur les cas par secteur occupationnel et pour les refuges pour les personnes en situation d’itinérance.

Conclusion

Un an après le début de la pandémie, la disponibilité des données sur la COVID-19, stratifiées par marqueurs sociaux, reste très limitée au Canada. Cependant, plusieurs « bonnes pratiques » en matière de déclaration axée sur l’équité en matière de santé ont été observées, ce qui constitue un précédent pertinent que les juridictions pourront suivre pendant cette pandémie et celles à venir.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Early reporting by regional and provincial jurisdictions in Canada suggests that, as has been the case in other countries such as the United States (USA) (Chen et al. 2020; Moore et al. 2020), social inequities in COVID-19 outcomes have emerged. In Ontario, for instance, higher rates of COVID-19 incidence, hospitalization, and death have been observed in lower-income areas and areas with higher densities of immigrant and racialized residents (Chung et al. 2020). Toronto has reported that 83% of COVID-19 cases with available race/ethnicity data, identified between mid-May and mid-July 2020, occurred among racialized residents, despite these residents representing 52% of the city’s population (Toronto Public Health 2020).

These early reports of social inequities in COVID-19 outcomes beg several questions for public health policy and intervention. Since the identification of these inequities is predicated on the availability and release of COVID-19 surveillance data according to social markers, one fundamental question is how Canada is doing, overall, in health equity-informed COVID-19 data reporting across jurisdictions? Knowing which inequities have emerged, and where, is a necessary first step in planning health equity-informed health policy and interventions (Blair et al. 2018; Frank and Matsunaga 2020; Moore et al. 2020).

Indeed, public release and reporting on surveillance data have been essential to inform epidemiologic research and modelling and public health interventions since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Presenting data disaggregated by social markers, such as sex or race/ethnicity, can ensure that social and political responses to the health crisis are sensitive to and designed to be effective against social disparities in outcomes (Childs and Palmieri 2020). Data transparency also serves to protect the public’s trust in public health guidelines and ensure accountability (Brison 2018). However, given that provincial and territorial rather than federal public health authorities are the primary entities collecting and reporting on health data in Canada, public-facing output on local- or social marker-disaggregated data can vary across Canadian jurisdictions. An assessment of both overall and health equity-oriented COVID-19 data reporting in each Canadian province and territory is needed to identify both best practices and reporting gaps.

The objective of this study was to perform an environmental scan of COVID-19 data reporting across Canadian provinces and territories and to assess health equity-focused reporting using a scorecard approach. Scorecards can be used to help track health-related trends or the quality of data reporting across jurisdictions (MHASEF Research Team 2018). Here, we build on the USA-based Coronavirus in Kids (COVKID) Tracking and Education Project’s recently proposed COVKID State Data Quality Report Card (Pathak et al. 2020) which was designed to identify gaps in COVID-19 surveillance in children. We propose the Canadian COVID-19 Health Equity Data Scorecard as an evaluation framework for the Canadian context.

Method

Data

A detailed environmental scan of official provincial and territorial public health websites and published reports was performed to identify data reporting content. Reference websites used were those provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada on their centralized reporting website (Public Health Agency of Canada 2020a). Provincial and territorial websites were searched for data summaries, figures, and tables as well as downloadable reports (most often available in portable document (PDF) format), by navigating through websites and downloading and reviewing reports. The results are accurate up to December 31, 2020. This scan represents a summary of Canadian reporting as of approximately one year after the identification of the first cases of COVID-19 (World Health Organization 2020).

Scorecard indicators

Based on the minimum data requirements proposed by extant COVID-19 data quality assessments, such as the COVKID Project Data Quality Report Card (Pathak et al. 2020), we assessed provinces’ and territories’ reporting of five data elements: cumulative totals of tests performed, case counts, hospitalizations, and deaths, as well as the availability of data on the size of populations of interest. Population size was not included in the COVKID Report Card assessment. However, it is included here insofar as it is necessary for rate estimation and relative comparisons across jurisdictions and groups.

As the COVKID Report Card does for each state, we assessed the availability (and the availability of explicit operational definitions) of these five data elements across provinces and territories, overall. We also assessed reporting on two additional levels of population aggregation: health region or unit level, and Forward Sortation Area-level or small neighbourhood area equivalent. Reporting on various levels of spatial aggregation was assessed given that transmission epidemiology and distributions of risk factors can vary across jurisdictions and localities.

Across these levels of aggregation, we also assessed data reporting across eight equity-related indicator strata. Building on the COVKID Report Card’s assessment of reporting across age and race/ethnicity, we assessed reporting across individual-level exposure to four congregate living and institutional settings that are vulnerable to COVID-19 outbreaks (long-term care and detention facilities, homeless shelters, and schools) (Blair et al. 2020; Hsu et al. 2020; Public Health Ontario 2020a; Richard et al. 2021) and eight individual-level social markers (age, sex, immigration status, race/ethnicity, healthcare worker status, occupational sector, and income and education groups). The latter social markers have been identified as key social determinants of health and infectious disease burden (Semenza et al. 2016; Solar and Irwin 2010). These individual-level social, economic, and occupational data would typically be obtained at testing, during case interviews, or via data linkage to existing provincial or territorial health and social administrative databases. With the five data elements across three units of population aggregation—overall and across twelve social strata—195 indicators were used (5 * 3 * (1 “overall” population-level stratum + 12 social strata) = 195).

As done for other scorecards, these indicators were selected for being measurable, relevant for health equity surveillance, actionable, and interpretable (Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences 2018). Indeed, precedent exists for surveillance reporting across all social markers used, including by race/ethnicity (CDC 2020; New Zealand Ministry of Health 2020) and occupational sector (Iowa Department of Public Health 2020)—if not for COVID-19, for other common health outcomes (Agic et al. 2013; Public Health Agency of Canada 2020a; Stachenko 2008).

Analysis

For each of the 195 indicators, 1 point was awarded if raw, anonymized individual case-delimited data were released and publicly available (i.e., where each case represented one data row, available in a downloadable, and editable file format, such as in Comma Separated Values (.csv) format). A total of 0.7 points was awarded if summary statistics were reported for the indicator, but no raw case-delimited data were publicly available, and a score of 0 was awarded if neither information was reported nor data made publicly available. To contrast surveillance reporting across jurisdictions at a national scale, points were only awarded if the data element was available for the entire jurisdiction (i.e., not if data were only available for certain regions).

We used a near-complete (0.7 points; intentionally higher than a half-point) and complete (1 point) scoring system rather than a binary (present/absent, 0 vs. 1 point) method to acknowledge the relevance of summary statistic reporting, while rewarding jurisdictions that opted for full data transparency for public use—as done in peer nations such as the United Kingdom (UK Data Service 2020) and the USA (USA Facts 2020). Raw data sharing has been identified as a best practice in supporting innovation and research, advancing government accountability and evidence-informed decision-making (Brison 2018; Lindquist and Huse 2017; Roy 2014). It also allows for an intersectional assessment of indicators. For example, the child health-focused COVKID scorecard found that though many states report on COVID-19 outcomes by age and race, a limited number of states report on the race of cases by age group (thereby allowing for an assessment of racial disparities among children) (Pathak et al. 2020). The sharing of case-delimited data allows users to pursue these more precise lines of inquiry.

For each level of aggregation, a percent score was estimated based on overall population-level data availability (score out of 5 data elements) and based on “equity” data across social strata (5 data elements * 12 social strata = score out of 60). A summary percent score was computed for population-level data overall (5 data elements * 3 population aggregation units = total score out of 15) and for equity-related data (5 data elements * 3 population aggregation units * 12 social strata = total score out of 180).

We adjusted score denominators to take into account that reporting on some of the indicators, such as the cumulative total of deaths or hospitalizations, is less relevant in jurisdictions without any recorded cases or when case numbers are so low (i.e., n < 5) that reporting may jeopardize patient confidentiality. When the total number of observations needed to estimate the indicator was less than 5, the indicator was removed from the score’s denominator total. In that way, if one jurisdiction had not recorded any COVID-19 cases, for example, it was not penalized for not reporting on cases by age and sex. Last, the following letter grades were associated with documented percent scores: 0–39% as “F” (very poor), 40–59% as “D” (poor), 60–69% as “C” (fair), 70–79% as “B” (good), 80–89% as “A” (very good), and 90–100% as “A+” (excellent).

Results

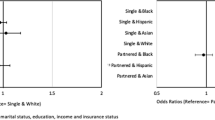

Scores were estimated for each province and territory, and Canada overall (Fig. 1, with detailed scores and sources in Supplementary File, eTable 1). On average, over half (58%, “D” score) of the data elements were available at the overall jurisdictional, health region, and local neighbourhood levels, while just under one in five (17%, “F” score) equity-related data elements were available.

Though all jurisdictions reported on the types of tests used to identify SARS-CoV-2 infections, clear case definitions were not always available, and definitions of what was counted as a COVID-19 hospitalization or death were often missing (eTable 2).

Overall population-level data reporting

By province and territory

At the province and territory level, data availability scores ranged from “C” (62–68%) for Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nunavut, and the Yukon to “A” (82–88%) for British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario. On average, 73% (“B”) of data elements were available at the province and territory level in Canada (Fig. 1).

All provinces and territories reported on the total number of tests, cases, and deaths (Fig. 2), with British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario providing case-delimited data for all cases observed (Fig. 2b). Alberta and Ontario were the only two provinces that also reported on the outcomes (recovery or death) for each case, in a downloadable case-delimited format. Though most jurisdictions reported on the total number of hospitalizations that have occurred, these data were not provided by Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, nor the three territories (Fig. 2c). Population denominators for all jurisdictions were available through the Canadian Census.

By health region

For reporting by health regions within jurisdictions, population data availability scores ranged from “F” (25–34%) for Nova Scotia, Nunavut, and the Yukon to “A” (82–88%) for British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario (Fig. 1). On average in Canada, 59% (“D”) of data elements were available for regions within jurisdictions.

The overall number of tests conducted per health region was available for 8 out of 13 jurisdictions (Fig. 3a). Quebec, one of the provinces hit hardest by the pandemic (Public Health Agency of Canada 2020a), did not report on total tests conducted per region. In contrast, reporting on the total number of cases per health region was more complete, with British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario standing out as provinces that provide data on the region of residence for all identified cases (Fig. 3b). Overall, most provinces that reported on overall hospitalizations (Fig. 2c) also provided summaries of hospitalizations per health region (Fig. 3c)—New Brunswick was the exception to this rule. Except for Nova Scotia, data on deaths per health region were available for all jurisdictions reporting over five deaths (Fig. 3d). Last, population denominators for all health regions within jurisdictions were available from Statistics Canada’s Canadian Census.

By Forward Sortation Area or the local neighbourhood area equivalent

Population denominators are made available by Statistics Canada for all Forward Sortation Areas in Canada. Overall, no jurisdictions reported on the cumulative total of hospitalizations at the local area level. None but Nunavut reported on the overall number of tests undertaken at the local level. Very few jurisdictions reported on the number of cases or deaths by local area. Exceptions were Alberta, with its reporting on the number of cases and deaths for all local areas of residence, and Ontario’s case-delimited dataset, which included the postal code associated with each death.

Overall, data availability scores for population data at the local area level ranged from “F” (20–25%) for most jurisdictions to “D” (48%) for Alberta and “C” (60%) for Ontario. On average in Canada, 27% (“F”) of data elements were available for local areas within jurisdictions (Fig. 1).

Equity-oriented reporting by social markers and vulnerable settings

On average in Canada, 17% (“F”) of data elements were available across identified equity-oriented social markers and vulnerable settings at the province and territory level (Fig. 1). Scores were lower for equity data reporting across health regions and local areas (average scores of 16% and 15%, respectively, for Canada overall).

By age and sex

Information on population sizes by age and sex overall, and for regions and local areas is made available by Statistics Canada, through the Canadian Census. Of all the social markers studied, age and sex were the characteristics for which COVID-19 data reporting was most common. All provinces except for New Brunswick reported on cases’ age and sex distribution at the population level (Fig. 4). None of the territories reported on cases’ age or sex (Fig. 4). British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario were the only three provinces that provided age and sex characteristics of all cases, in a case-delimited format.

Reporting on the cumulative total of tests, cases, hospitalizations, and deaths by social markers and settings. BC, British Columbia; AB, Alberta; SK, Saskatchewan; MB, Manitoba; ON, Ontario; QC, Quebec; NB, New Brunswick; NS, Nova Scotia; PE, Prince Edward Island; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; NU, Nunavut; NT, Northwest Territories; YT, Yukon; LTC, long-term care settings

In contrast, age- and sex-related information was sparser for testing, hospitalizations, and deaths across all jurisdictions overall and by health regions. Only Ontario consistently reported on all data elements by age and sex at the overall provincial and health region level (Fig. 4).

Sex disaggregation was mostly done according to designations of “male” and “female.” However, Ontario also included categories of “Other” and “Unspecified” and British Columbia included the category “Unknown” (eTable 2). Age disaggregation was mostly done for 10-year age groups—consistently from ages <20, 20–39, 40–49, etc. to 80 years and above (eTable 2). New Brunswick, Quebec, Manitoba, Alberta, and British Columbia also included categories for those under 10 years—with Alberta also reporting on data for additional age ranges of <1, 1–4, and 5–9 years (eTable 2).

Immigration, race/ethnicity, income, education

Though information on population sizes by immigration status, race/ethnicity, income, and education is available through the Canadian Census for jurisdictions overall, as well as by region and local area, no province or territory reported on any of the data elements according to these social markers (Fig. 4).

Healthcare worker status and occupational sector

At the overall provincial level, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario provided information on cases among essential healthcare workers—with Alberta and Ontario providing this information at both the province and territory and regional levels (Fig. 4). However, the total number of healthcare workers at the provincial or territorial level, or by region or local area, was missing for all jurisdictions.

Only Ontario provided details on the number of cases across occupational sectors beyond the healthcare setting (e.g., farm, food processing, retail) (eTable 1).

Vulnerable settings (long-term care and detention facilities, homeless shelters, schools)

Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba reported on the number of cases associated with long-term care (LTC) facilities—with British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec also reporting on deaths within these facilities. Ontario and Quebec listed precise facilities (that could be geolocated in local areas) that had or were experiencing outbreaks. Saskatchewan provided current case counts for precise LTC facilities on a weekly, rather than cumulative, basis. In Ontario and Quebec, the total number of tests and hospitalizations recorded for patients or staff in these settings was missing. Only Ontario provided data on tests within LTC facilities, as well as the total number of beds per facility experiencing an outbreak—which could be used as a proxy for patient population size.

Quebec and Ontario were the only provinces that reported on the total number of cases for each provincial detention facility. Of these two, Quebec was the only province to report on the total number of tests, deaths, number of prisoners, and cases among staff per facility. Missing, however, was information on cases’ potential hospitalization status.

For school settings, only case totals were reported in Ontario and Quebec. Ontario was also the only province to explicitly report on case totals associated with homeless shelters.

Discussion

This paper provides the first summary of health equity-related COVID-19 data reporting in Canada within the first year since the first COVID-19 case was identified in Wuhan, China. In Canada, information on cases and deaths was more complete than that for tests, hospitalizations, and population denominators for all indicators. Jurisdictions tended to report more completely on overall statistics than on information for regions or local areas, or according to population subgroups. The scan suggests that large gaps in reporting remain, even for more standard social disaggregation markers such as age and sex. Though relatively uncommon across the country, certain “best practices” in reporting emerged. For example, three provinces (Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario) provided case-delimited data on cases for external users to study. Alberta and Ontario provided case-delimited data that included cases’ local area-level identifiers, enabling localized spatial analyses. Almost half of the provinces provided case counts associated with LTC settings, with Ontario and Quebec listing individual facilities that had or were experiencing outbreaks in the province—which can enable the precise geo-location of facilities within neighbourhoods, for use in socio-spatial analyses of transmission risk. Ontario stood out in its reporting of cases across the largest range of equity strata, including across schools, homeless shelters, and occupational sectors outside of healthcare. Last, though Ontario and Quebec both provided details on cases within provincial detention facilities, Quebec was alone in providing detailed information on COVID-19 tests, deaths, prisoner population size, and cases within staff populations per detention facilities. These examples set important precedents and guidance for other jurisdictions to follow, especially as emerging evidence suggests that if COVID-19 outcomes are properly examined across population subgroups, underlying inequities can be revealed and addressed (Chung et al. 2020; Toronto Public Health 2020).

Heterogeneities in reporting observed across Canada are aligned with previous findings that public health surveillance infrastructures and capacities tend to vary across jurisdictions in Canada—which had been identified as an area of concern for pandemic planning and preparedness following the SARS outbreak in 2003 (Naylor 2003). This variability in resources across jurisdictions may limit capacities to collect necessary social data and report on findings across settings or social markers. Since the availability of individual-level equity-related data would typically be obtained at testing, during case interviews, or via data linkage to existing administrative databases, several situations may jeopardize equity-related data collection and reporting. For example, there may be provinces or territories for which these types of databases may not exist or be limited in scope, or for which COVID-19 testing intake or case interview questionnaires are missing items on social, economic, or occupational characteristics. When faced with elevated testing and caseloads and limited time to collect and report on a wide range of indicators, lower personnel capacity can require the prioritization of a subset of case interview elements that exclude equity-related items. For settings such as long-term care homes, detention facilities, schools and homeless shelters, collection and reporting on cases and population sizes requires intersectoral collaboration and communication between public health and other governmental sectors, as well as with the private or community sectors.

To overcome these challenges, formal exchange of promising practices, through meetings at federal and provincial and territorial levels, between public health, healthcare, and community-level stakeholders may be beneficial. These can foster communication on existing barriers to equity-related data collection and reporting, as well as promising practices—be it on equity-related data collection and reporting guidelines (Government of Ontario 2019), questionnaires for social data collection (Agic et al. 2013), intersectoral collaboration strategies, or data communication. National guidance can be developed to ensure the quality and comparability of data collected across jurisdictions, which respects fundamental principles such as those pertaining to Indigenous data sovereignty. An example of this is the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s Proposed Standards for Race-Based and Indigenous Identity Data Collection and Health Reporting in Canada (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2020). Indeed, the Public Health Agency of Canada’s COVID-19 Case Report Form was updated in October 2020 to include more detailed items on cases’ dwelling type (including correctional facility, long-term care, homeless shelter), race/ethnicity, temporary foreign worker status, and occupation, which can be used across provinces and territories for more detailed reporting (Public Health Agency of Canada 2020b). Additional equity-informed elements (e.g., education level) could be added to this case report form or those for use in future pandemics. It will also be essential to assess how these guidelines and tools are applied across jurisdictions, to allow for national reporting on social inequalities.

In the context of other major public health phenomena, such as rising diabetes rates in Canada, successful strategies to guide public health practice included the development of a national action plan, which yielded the development of performance measures, knowledge mobilization strategies, funding mechanisms to support research and community programs, a joint surveillance plan with First Nations, Métis, and Inuit partners, and feasibility studies of the use of health administrative data linkages for surveillance (Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, & Canadian Institutes of Health Research 2013). Similar steps may also be fruitful for determining what data should be collected, and how they can be collected and shared to improve equity-informed reporting and decision-making on COVID-19 and other health phenomena.

The scorecard approach presented here can be used for continued assessments of COVID-19 surveillance reporting or adapted for use in future infectious disease outbreaks. The COVKID scorecard database has been updated twice (August and May 2020) (Pathak et al. 2020). An update of a scan and scorecard such as the one presented here would be beneficial every year, at minimum, which corresponds to the frequency of reporting for infectious disease-related outcomes and targets in Canada (Public Health Agency of Canada 2020c). Updating the scan as of December of every year would provide a useful portrait of reporting progress since the first cases of COVID-19 were identified on December 31, 2019 (World Health Organization 2020).

However, the scorecard approach used has certain limitations. For one, a restricted list of social marker indicators was used. Future expanded versions of an equity-oriented scorecard could assess COVID-19 outcome reporting according to indicators such as preferred language, year of immigration, disability status, sexual orientation, household crowding, gender, or Indigenous identity (Agic et al. 2013). Second, by evaluating provincial or territorial reporting, this scorecard assessment did not address more detailed reporting efforts in specific public health units within jurisdictions. For instance, detailed neighbourhood-level reporting efforts have been made by Montreal Public Health (Direction de la santé publique de Montréal 2020) and several public health units in Ontario (Public Health Ontario 2020b), including Toronto Public Health’s reporting on cases by income and race/ethnicity (Toronto Public Health 2020). In Manitoba, First Nations partners have collaborated to provide a report of tests, cases, hospitalizations, and deaths among First Nations people living on and off reserve (Manitoba First Nations COVID-19 Pandemic Response Coordination Team 2021). The present scan was restricted to provincial and territorial reporting to contrast among jurisdictions on a national scale. Future scans of best data collection and reporting practices across levels of governance may be warranted. Further, this scan excludes information sharing by federal bodies, such as the Correctional Service of Canada’s reporting on cases within federal penitentiaries (CSC 2020). Future assessments of federal-level reporting may also be warranted.

Conclusion

Though several “best practices” in health equity-oriented reporting were observed in Canada, equity data reporting is sparse and large gaps remain. Since jurisdictions that have explored potential social inequities in COVID-19 indicators have found stark gradients in outcomes across individual- and local-area level characteristics, the absence of reporting of data according to vulnerable settings or social markers may be concealing broader COVID-19-related inequities in Canada. The proposed scorecard format and examples of “best practices” identified herein can be used to guide surveillance and reporting during this pandemic and in future ones, and monitor progress on health equity-informed reporting overall.

Data Availability

Results are summarized in the Supplementary File (eTable 1).

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Agic, B., McKeown, D., McKenzie, K., Pinto, A., & Sinha, S. (2013). We ask because we care: the Tri-Hospital + TPH Health Equity Data Collection Research Project Report. Toronto, Canada. http://www.stmichaelshospital.com/quality/equity-data-collection-report.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Blair, A., Siddiqi, A., & Frank, J. (2018). Canadian report card on health equity across the life-course: analysis of time trends and cross-national comparisons with the United Kingdom. SSM-population health, 6, 158–168.

Blair, A., Parnia, A., & Siddiqi, A. (2021). A time-series analysis of testing and COVID-19 outbreaks in Canadian federal prisons to inform prevention and surveillance efforts. Can Commun Dis Rep, 47(1):66–76. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v47i01a10.

Brison, S. (2018). Canada’s 2018-2020 National Action Plan on Open Government. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Canada_Action-Plan_2018-2020_EN.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2020). Proposed Standards for Race-Based and Indigenous Identity Data Collection and Health Reporting in Canada. https://www.cihi.ca/en/proposed-standards-for-race-based-and-indigenous-identity-data. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

CDC. (2020). COVID-NET: COVID-19-associated hospitalization surveillance network. https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/COVIDNet/COVID19_5.html. Accessed 22 June 2020.

Chen, J. T., Waterman, P. D., & Krieger, N. (2020). COVID-19 and the unequal surge in mortality rates in Massachusetts, by city/town and ZIP Code measures of poverty, household crowding, race/ethnicity, and racialized economic segregation. Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies Working Paper Series, 25014(B25014_013E), B25014_25001E.

Childs, S., & Palmieri, S. (2020). A primer for parliamentary action gender sensitive responses to COVID-19. https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/a-primer-for-parliamentary-action-gender-sensitive-responses-to-covid-19-en.pdf?la=en&vs=2013. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Chung, H., Fung, K., Ferreira-Legere, L.E, Chen, B., Ishiguro, L., Kalappa, G., Gozdyra, P., Campbell, T., Paterson J.M., Bronskill, S.E., Kwong, J.C., Guttmann, A., Azimaee, M., Vermeulen, M.J., Schull M.J. (2020). COVID-19 Laboratory testing in Ontario: patterns of testing and characteristics of individuals tested, as of April 30, 2020. Toronto, Canada. https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2020/COVID-19-Laboratory-Testing-in-Ontario. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

CSC. (2020). Correctional Service of Canada: inmate COVID-19 testing in federal correctional institutions, April 21, 2020. https://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/001/006/001006-1014-en.shtml. Accessed 21 Apr 2020.

Direction de la santé publique de Montréal. (2020). Situation of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Montreal. https://santemontreal.qc.ca/en/public/coronavirus-covid-19/situation-of-the-coronavirus-covid-19-in-montreal/#c43674. Accessed 23 June 2020.

Frank, J. W., & Matsunaga, E. (2020). National monitoring systems for health inequalities by socioeconomic status – an OECD snapshot. Critical Public Health, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2020.1862761.

Government of Ontario. (2019). Data standards for the identification and monitoring of systemic racism. https://files.ontario.ca/solgen_data-standards-en.pdf. Accessed 29 June 2020

Hsu, A.T., Lane, N., Sinha, S.K., Dunning, J., Dhuper, M., Kahiel, Z., & Sveistrup, H. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on residents of Canada’s long-term care homes–ongoing challenges and policy response. International Long-Term Care Policy Network, 17. https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LTCcovid-country-reports_Canada_Hsu-et-al_May-10-2020-2.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Iowa Department of Public Health. (2020). COVID-19 in Iowa: positive case analysis. https://coronavirus.iowa.gov/pages/case-counts. Accessed 22 June 2020.

Lindquist, E. A., & Huse, I. (2017). Accountability and monitoring government in the digital era: promise, realism and research for digital-era governance. Canadian Public Administration, 60(4), 627–656.

Manitoba First Nations COVID-19 Pandemic Response Coordination Team. (2021). First Nations COVID-19 Bulletin. https://www.fnhssm.com/covid-19. Accessed 28 Jan 2021.

MHASEF Research Team. (2018). Mental Health and Addictions System Performance in Ontario: A Baseline Scorecard. Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. ISBN 978-1-926850-79-5. https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2018/MHASEF. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Moore, J.T., Ricaldi, J.N., Rose, C.E., Fuld, J., Parise, M., Kang, G.J., COVID-19 State, T., Local, and Territorial Response Team. (2020). Disparities in incidence of COVID-19 among underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in counties identified as hotspots during June 5–18, 2020 — 22 states, February–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6933e1external

Naylor, C.D. (2003). Learning from SARS: renewal of public health in Canada: a report of the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health: National Advisory Committee.

New Zealand Ministry of Health. (2020). COVID-19: current situation - current cases. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases#dhbs. Accessed 22 June 2020.

Pathak, B., Menard, J., & Salemi, J. (2020). The Coronavirus in Kids (COVKID) Tracking and Education Project: state report card. https://www.covkidproject.org/state-report-card. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2020a). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): epidemiology update. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html#a8. Accessed 19 June 2020.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2020b). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) case report form - October 1, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/health-professionals/2019-nCoV-case-report-form-en.pdf. Accessed 28 Jan 2021.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2020c). Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) 2018–19 Departmental results report: supplementary information tables. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/transparency/corporate-management-reporting/departmental-performance-reports/2018-2019-supplementary-information-tables.html. Accessed 28 Jan 2021.

Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, & Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2013). Health Portfolio Action Plan and Progress Report in response to audit findings and recommendations contained in Chapter 5 “Promoting Diabetes Prevention and Control” of the Spring 2013 report of the Auditor General of Canada. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/412/PACP/WebDoc/WD6272639/Action_Plans/10-PHACActionPlan-e.htm. Accessed 28 Jan 2021.

Public Health Ontario. (2020a). COVID-19 in Ontario: elementary and secondary school outbreaks and related cases, August 30, 2020 to November 7, 2020. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/epi/2020/12/covid-19-school-outbreaks-cases-epi-summary.pdf?la=en. Accessed 28 Jan 2021.

Public Health Ontario. (2020b). Learning exchange: discussion on local socio-economic data during COVID-19, June 24, 2020 - recorded webinar. https://pho.adobeconnect.com/pdqpi9f8uyz7/. Accessed 29 June 2020.

Richard, L., Booth, R., Rayner, J., Clemens, K. K., Forchuk, C., & Shariff, S. Z. (2021). Testing, infection and complication rates of COVID-19 among people with a recent history of homelessness in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open, 9(1), E1–e9. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20200287.

Roy, J. (2014). Open data and open governance in Canada: a critical examination of new opportunities and old tensions. Future Internet, 6(3), 414–432.

Semenza, J. C., Lindgren, E., Balkanyi, L., Espinosa, L., Almqvist, M. S., Penttinen, P., & Rocklov, J. (2016). Determinants and drivers of infectious disease threat events in Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 22(4), 581–589. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2204.

Solar, O., & Irwin, A. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. WHO Document Production Services. https://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2021.

Stachenko, S. (2008). Challenges and opportunities for surveillance data to inform public health policy on chronic non-communicable diseases: Canadian perspectives. Public Health, 122(10), 1038–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2008.05.006.

Toronto Public Health. (2020). COVID-19 infection in Toronto: ethno-racial identity and income. COVID-19: Status of Cases in Toronto. https://www.toronto.ca/home/covid-19/covid-19-latest-city-of-toronto-news/covid-19-status-of-cases-in-toronto/. Accessed 11 Aug 2020.

UK Data Service. (2020). COVID-19 data. https://www.ukdataservice.ac.uk/get-data/themes/covid-19/covid-19-data.aspx. Accessed 19 June 2020.

USA Facts. (2020). Coronavirus Locations: COVID-19 Map by County and State - COVID-19 deaths dataset. https://usafacts.org/visualizations/coronavirus-covid-19-spread-map/. Accessed 23 June 2020.

World Health Organization. (2020). Pneumonia of unknown cause – China, 5 January 2020. Disease outbreak news. [Web Archive] https://web.archive.org/web/20200130204239/; https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/. Accessed 27 Jan 2021.

Funding

AB receives postdoctoral funding from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé. AS is supported by the Canada Research Chair in Population Health Equity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB, AP, and AS designed the scorecard framework. KW, HN, WB, and AB performed the environmental scan and collected the data for the study. AB drafted the manuscript, which was revised by AS, AP, KW, HN, and WB.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

None required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 101 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blair, A., Warsame, K., Naik, H. et al. Identifying gaps in COVID-19 health equity data reporting in Canada using a scorecard approach. Can J Public Health 112, 352–362 (2021). https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00496-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00496-6