Students’ academic procrastination during the COVID-19 pandemic: How does adversity quotient mediate parental social support?

- 1Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Ahmad Dahlan University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- 2Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan

- 3Faculty of Psychology, Ahmad Dahlan University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- 4Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences and Liberal Arts, UCSI University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

The COVID-19 has had a widespread impact on all aspects of life. The government has undertaken numerous restrictive attempts to sever the virus transmission chain. In the education sector, one of the attempts is to apply certain learning models. For instance, the online model has been used in place of the face-to-face one across all academic and non-academic services. Educators have faced several obstacles, including academic procrastination. Academic procrastination refers to intentionally putting off working on an assignment, which negatively influences academic achievement. This study aimed to examine the role of parental social support in academic procrastination with the mediation of the adversity quotient. The subjects consisted of 256 state Madrasah Aliyah students in Magelang aged 15–18 years (M = 16.53, SD = 1.009). Data collection employed the academic procrastination scale, parental social support scale, and adversity quotient scale. Data analysis used descriptive statistics and structural equation modeling (SEM) with the aid of the IBM SPSS 23 and AMOS Graphics 26. The research results showed that all variables fell into the medium category. Parental social support had a negative role on academic procrastination and a positive one on adversity quotient. Meanwhile, the adversity quotient had a negative role in academic procrastination and a significant role as a mediator in the relationship between parental social support and academic procrastination. Therefore, parental social support is required to increase students’ adversity quotient in suppressing academic procrastination. Special attention from parents to students is thus critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the mediation of adversity quotient.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, learning and teaching activities are experiencing systemic alterations from offline to online-based. Nearly all over the world, students face the challenges of independent learning, learning on the computer, and a lack of contact with teachers and peers, thereby demanding sound time management (Pelikan et al., 2021). This learning model is unprecedented in educational systems around the globe, and this is particularly true in Indonesia, where understanding of information technology (IT) has yet to be equal on all lines. The online learning model requires thorough, systematic preparation, but the state of emergency in which it is implemented has spawned a multitude of issues, both academic and non-academic. A frequent issue among them is academic procrastination, which refers to students’ purposeful deferment in various academic activities, which is extensively impactful on their future (Wiguna et al., 2020; Pelikan et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2021; Laia et al., 2022). There has been a significant rise in academic procrastination among students (Tezer et al., 2020; Pelikan et al., 2021; Buana et al., 2022), and this phenomenon during the online learning policy is confirmed by previous studies that suggest that online learning is linked to the postponement of completing tasks related to the learning (Steel and Klingsieck, 2016). Students procrastinate although it may lead to negative consequences (Goroshit, 2018). It results in students’ low final grades (Kljajic and Gaudreau, 2018). Students put off completing academic work for several reasons, do and submit tasks late, and face difficulties in time management in learning (Laia et al., 2022). If the indiscipline habit is left uncorrected, it will result in a bad mentality for students’ psychological development (Zacks and Hen, 2018; Amir et al., 2020; Maqableh and Alia, 2021; Peixoto et al., 2021; Pelikan et al., 2021; Prasetyanto et al., 2022).

Despite realizing that it has negative effects, students still engage in academic procrastination for internal or external reasons. Still, due to the pandemic situation, some teachers consider it normal and understandable. Some factors associated with academic procrastination are weak learning dedication, low learning performance, and poor learning objectives achievement (Tian et al., 2021). Academic procrastination is spurred by certain situations, including task difficulty and low task attractiveness, being compelled to learn autonomously, and unattractive teacher characteristics (Klingsieck, 2013). Students experience difficulties in learning and managing the learning process and lack independence and maturity, thereby finding it difficult to motivate themselves, especially when faced with difficult, lengthy learning tasks (low adversity quotient) (Zacks and Hen, 2018). Other reasons include the unattractive way of delivering materials, difficulty adapting to online learning, connection instability, and extra financial burden to access the Internet (Amir et al., 2020; Maqableh and Alia, 2021; Peixoto et al., 2021; Pelikan et al., 2021; Prasetyanto et al., 2022). In addition, there are issues of ineffectively delivered curriculum and a lack of interaction between teacher and student or between student and student (Mohalik and Sahoo, 2020). Students also have difficulty concentrating when learning, psychological problems, and poor time management (Maqableh and Alia, 2021). They are often confused about completing their tasks because the instructions are hard to understand (Peixoto et al., 2021). Besides, procrastination can also result from laziness in completing the tasks from the teacher and low learning motivation (Pelikan et al., 2021). The following issues are also present: the homework given by the teacher overweight’s the assignment given during face-to-face meetings; the intensity of looking at a laptop or handphone screen causes disturbance to health; the conditions at home make it difficult to stay focused; being burdened by other works; vagueness in the teacher’s explanation; and difficulty discussing with or asking questions to the teacher (Prasetyanto et al., 2022). Finally, the unattractiveness of the online learning model serves as an important factor in the high degree of procrastination during COVID-19 (Latipah et al., 2021; Prasetyanto et al., 2022).

Following the description above, it is necessary to further scrutiny the students’ academic procrastination during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, research among senior high school students in Indonesia is still limited to the non-Islamic-based school (Latipah et al., 2021; Habibi et al., 2022; Irawan and Widyastuti, 2022). Studies showed that 47.2% of senior high school (SMA) students in Temanggung engaged in a medium level of academic procrastination (Latipah et al., 2021), 34.3% of vocational high school (SMK) students in Bojonegoro demonstrated a medium level of academic procrastination (Irawan and Widyastuti, 2022), and 652 or 78.6% state senior high school (SMAN) students in Mojokerto engaged in a medium level of academic procrastination (Habibi et al., 2022). Meanwhile, in Indonesia, Islamic-based senior high schools named Madrasah Aliyah also exist, numbering 9,131 or accounting for 24.6% of all schools at that level (Statistik, 2021; Kementerian Agama, 2022). Madrasah Aliyah (MA) is a public high school with an Islamic character administered by the Department of Religious Affairs (Suhardi, 2019). The curriculum load borne by MA students is higher than that of SMA and SMK students. The public senior high school (SMA) curriculum emphasizes the student’s theoretical mastery by providing in-depth general subjects (Putri, 2020). Meanwhile, the vocational high school (SMK) focuses more on students’ vocational skills to ensure students’ readiness to work in certain work fields (e.g., engineering, cuisine, hospitality, and craft industries, among others) (Putri, 2020). In Islamic high school (MA), students should learn Islamic knowledge, characters, and general knowledge like in SMA (Alawiyah, 2014). This difference poses MA students with issues of greater complexity in online learning during COVID-19 than those faced by non-Islamic-based school students (Latipah et al., 2021). Previous studies revealed that in online learning during COVID-19, 40.4% of students of state Madrasah Aliyyahs in Bengkulu demonstrated a high level of academic procrastination, and 28.6% even did a very high level of procrastination (Buana et al., 2022). These findings contrast with the SMA and SMK cases, where the students’ procrastination was within the medium category. Research on procrastination in the Madrasah Aliyah environment during COVID-19 is still minimal. Previous studies have examined the roles of self-efficacy and emotional intelligence on procrastination, but it was only focused on personal factors (Buana et al., 2022).

To enrich the literature on academic procrastination during online learning implementation, this research focused on Madrasah Aliyah. It included external (parental social support) and internal (personal) factors in reducing academic procrastination. Over the course of COVID-19, online learning took place at home. Therefore, parents’ involvement during the learning implementation is critical. Moreover, parents are the most prominent and pivotal figures in the provision of resources for children, hence holding a central place in creating social and emotional contexts (Wray-Lake et al., 2022).

Parental social support and academic procrastination in online learning

During COVID-19 in 2021, Indonesia still implemented online learning across all levels, including senior high school. Throughout online learning, students require parental social support for smooth learning, both financially and psychologically, since parents have the primary responsibility for their children’s education, including establishing social and emotional communication. However, many parents in Indonesia were found to be faced with psychological, social, and financial problems during COVID-19 (Kaligis et al., 2020; Alam et al., 2021; Anindyajati et al., 2021). Anxiety and stress problems in the family were also emerging (Anindyajati et al., 2021). Various hoaxes have triggered panic and fear (Kaligis et al., 2020). Problems also encompassed family’s financial problems caused by the social distancing policy, including decreased income, increased unemployment rate, and difficulty finding a new job, all of which undermined parental social support for children (Alam et al., 2021). Study results revealed that parents with children attending school during the early stage of COVID-19 in Indonesia were suffering from a moderate stress level due to having to allocate time for working from home and assisting their children in studying from home at the same time. Parents were also overwhelmed by their children’s assignments, especially mothers whose time was already mostly spent doing household chores and working from home (Susilowati and Azzasyofia, 2020). Thorell et al. (2021) discovered that online learning harmed parents’ lives by increased stress levels due to high workloads, fear that their children’s academic performance would drop, social isolation, and domestic conflict.

Although many parents encounter a multitude of difficulties that lead to psychological, social, and financial issues, parental social support occupies a core place within a crowded situation, raising students’ spirit albeit being under restrictions (Ikeda and Echazarra, 2021; Klootwijk et al., 2021; Maqableh and Alia, 2021). Research results reported a significant increase in parental social support during online learning from face-to-face learning, where parents felt a sense of responsibility for the online learning process (Wray-Lake et al., 2022). Parental social support appropriate to students’ needs during online learning may take the following forms: an internet facility, a material device such as a laptop or personal computer, and a home with a conducive environment for the learning (Maqableh and Alia, 2021).

Being related to various learning problems during online learning implementation, parental social support helps overcome academic procrastination optimally. A United States-based education longitudinal study on 15,240 ten graders showed that parents’ involvement in their children’s education, both at home and in school, had a significant effect on the children’s learning success (Benner et al., 2016). Results of another study on 313 upper secondary school students in Turkey showed that social support from the family contributed to academic procrastination (Erzen and Çikrıkci, 2018). Parental social support is pivotal and considerably influential to students’ social, psychological, and academic functions (Won and Yu, 2018). It was also reported that 177 United States parents of kindergarten to senior high school-aged children found it difficult to motivate their children to learn online (Garbe et al., 2020). Meanwhile, parental emotional support, such as motivational support, is grievously needed by students (Ikeda and Echazarra, 2021; Klootwijk et al., 2021). A lack of attention and learning motivation from parents for children are among the most responsible for the high level of academic procrastination behavior in online learning (Wulandari et al., 2021).

The effects of parental social support and adversity quotient on academic procrastination

Parental social support affects students’ adversity quotient and, subsequently academic procrastination. Parents, who are responsible for their children’s education and future, feel called to think about how their children will reach success in learning, so they try to provide their children with social and emotional support well and openly. This support raises the children’s motivation and spirit to put an effort to reach success, giving them the strength to take on challenges and hold on in the face of obstacles (Hidayati and Taufik, 2020). Adversity quotient is how well an individual persists in hardships and turns difficulties into opportunities (Stoltz, 2006). A qualitative study on students from low-income (poor) families and students falling victim to domestic violence or broken homes showed that parents had a strong association with adversity quotient development because the family is a motivator for students’ improved endurance (Hidayati and Taufik, 2020). Therefore, parents play an essential role in improving students’ adversity quotient. This is supported by the results of a study on 232 first-year students in Makassar, which revealed that parental social support had a role in forming the ability to cope with academic obstacles during the COVID-19 period (Sihotang and Nugraha, 2021). Parental social support may give the children opportunities to make decisions, provide a clear, consistent guide to their expectations and rules, and give the students adaptive and constructive responses to face academic obstacles (Sihotang and Nugraha, 2021).

Adversity quotient is essential for students during COVID-19. Given that during online learning, senior high school students in Indonesia face obstacles and barriers that may influence their learning quality and outcomes (Amir et al., 2020; Prasetyanto et al., 2022). With an adversity quotient, students can take situations under control, take advantage of opportunities, and have higher success chances (Juwita and Usodo, 2020). Research also unveiled that academic procrastination was influenced by the adversity quotient (Tuasikal et al., 2019). It stated that the higher the student’s adversity quotient, the lower the procrastination tendency, and the lower the student’s adversity quotient, the higher the procrastination tendency (Tuasikal et al., 2019).

Students need an adversity quotient to successfully deal with problems and fulfill their tasks and responsibilities in the online learning Field (Safi’i et al., 2021) and tackle academic issues (Parvathy and Praseeda, 2014). Students with high adversity quotients have a better self-motivation ability. In contrast, those with low adversity quotients will tend to give up and yield easily display pessimism, and exhibit a negative attitude (Stoltz, 2006). Earlier research findings showed that the adversity quotient affected students’ ability to adapt to online learning from offline learning, not excluding the ability to access and use online learning to establish a learning standard (Safi’i et al., 2021).

Present study

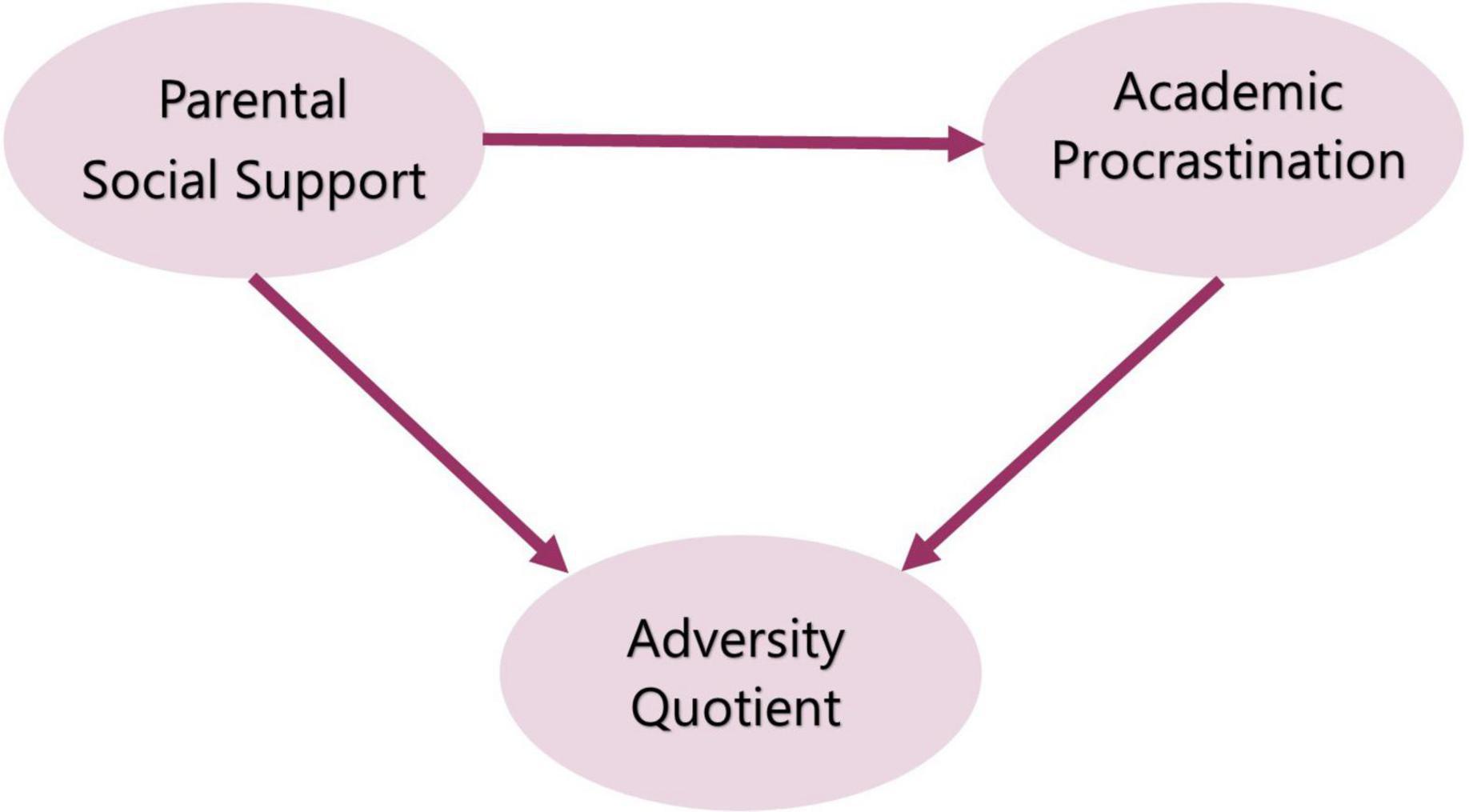

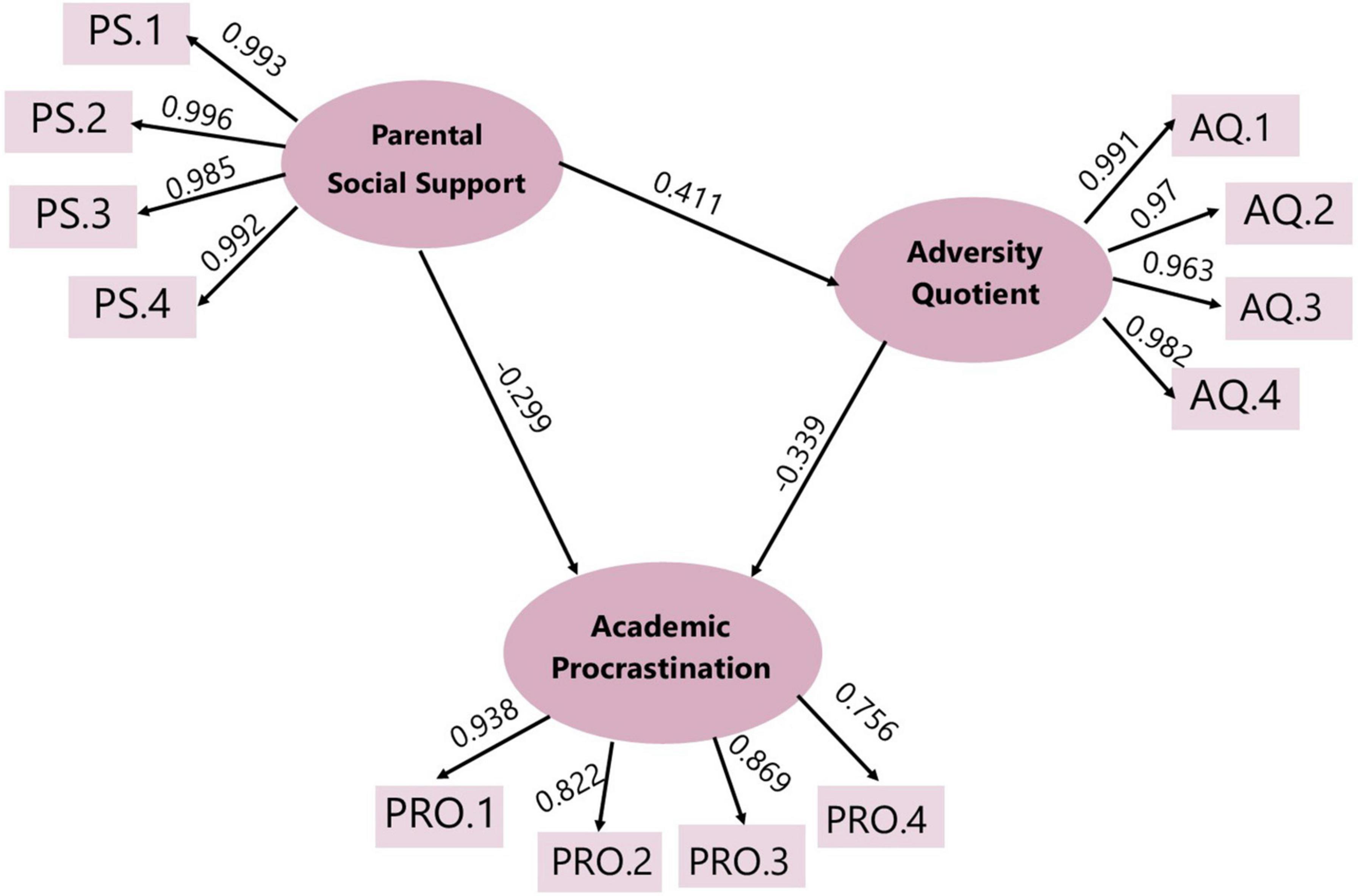

According to the explanation above, especially in the case of Madrasah Aliyah students, online learning has caused high levels of academic procrastination behavior. Earlier studies have explained that parental social support had a role in adversity quotient and academic procrastination, while adversity quotient had a role in academic procrastination. It can be concluded that parental social support contributes to students’ adversity quotient and subsequently affects academic procrastination. Thus far, there is minimal research on the mediating role of adversity quotient in the relationship between parental social support and academic procrastination. Therefore, the goal pursued by this research was to explain how parental social support influences academic procrastination with the mediation of adversity quotient in the case of Madrasah Aliyah students. The hypotheses model of this research is presented in Figure 1, while the hypotheses themselves are as follows:

H1: Parental social support has a negative role in academic procrastination.

H2: Parental social support has a positive role in the adversity quotient.

H3: Adversity quotient has a negative role in academic procrastination.

H4: Adversity quotient has a mediating role in the relationship between parental social support and academic procrastination.

Material and methods

Methods research participants and procedure

As many as 256 students from two Public Madrasah Aliyahs in Magelang aged 15–18 years (M = 16.53, SD = 1.009), consisting of 131 men and 125 women students, participated in this research. The participants were recruited by proportionate random sampling. This research acquired a research permit from Ahmad Dahlan University (F4/387/PS44/D.66/IV/2021) and from schools where this research was conducted. The researchers coordinated with school counselors to access participants’ phone numbers and form a WhatsApp group. Data collection was carried out using the Google Forms application. The researchers provided information on the research and instructions on completing the questionnaire via the WhatsApp group. Participants’ informed consent was asked ahead of the Google Forms questionnaire completion. Each participant spent around 15 min collecting the data. This research was conducted in July 2021.

Instruments

The academic procrastination scale was formulated using a 24-item Likert scale about the procrastination signs according to Ferrari Jonson and McCown: students put off starting and finishing a task, students complete a task late, there is a gap between the plan and the actual performance, and students prefer doing a more pleasurable activity (Ferrari et al., 1995). Four answer alternatives were used: SA (strongly agree), A (agree), D (disagree), and SD (strongly disagree). A higher score indicates a higher level of students’ procrastination. The academic procrastination scale was deemed valid (chi-square value of 14.58; p = 0.01), reliable (Cronbac’s alpha = 0.803), and having a fit model (CFI = 0.983; GFI = 0.73; TLI = 0.948; RMSEA = 0.098).

The parental social support scale was composed of 28 items. It took on the form of a Likert scale that was formulated about the social support aspects according to Sarafino and Smith; emotional support (a. empathy, b. comforting support); companionship support (a. spending time together, b. having a mutually supportive companionship bond); information support (a. receiving suggestions and advice, b. acquiring information); and instrumental support (a. non-material direct aid, b. action direct aid) (Sarafino and Smith, 2014). Four answer alternatives were used, namely SA (strongly agree), A (agree), D (disagree), and SD (strongly disagree). A higher score indicates higher students’ perceived parental social support. The parental social support scale was deemed valid (chi-square value of 15.978; p = 0), reliable (Cronbac’s alpha = 0.863), and having a fit model (CFI = 0.995; GFI = 0.71; TLI = 0.985; RMSEA = 0.099).

Lastly, the adversity quotient scale was a Likert scale with 22 items. This scale referred to Stolz’s dimensions, namely control, ownership, reach, and endurance (Stoltz, 2006). Five alternative responses were provided, namely SA (strongly agree), A (agree), N (neutral), D (disagree), and SD (strongly disagree). A higher score indicates a higher student’s adversity quotient. The adversity quotient scale was deemed valid (chi-square value of 6.278; p = 0.043) and reliable (Cronbac’s alpha = 0.863), and having a fit model (CFI = 0.998; GFI = 0.989; TLI = 0.994; RMSEA = 0.092).

Data analysis

Statistical-descriptive analysis was employed to gain an overview of each research variable. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was applied to assess the mediating role of adversity quotient in the relationship between parental social support and academic procrastination. This technique is commonly used to see the structural relationship between the measured variable and the latent construct by performing a simultaneous analysis like linear regression and path estimates. This study also measured the relationship between each aspect of parental social support and adversity quotient and academic procrastination, and the relationship between each aspect of parental social support and academic procrastination. It was done to identify the aspect with the highest contribution to academic procrastination and adversity quotient. The normality was done as a prerequisite of SEM-based on covariance. The goodness of fit index was evaluated using the following indices: probability, DF, CMIN/DF, GFI, NFI, CFI, IFI, TLI, and RMSEA (Kline, 2015). This research used the IBM SPSS 23 for the descriptive statistical analysis and normality test, and AMOS Graphics 26 for the Structural Equation Modeling.

Results

Variable descriptive data

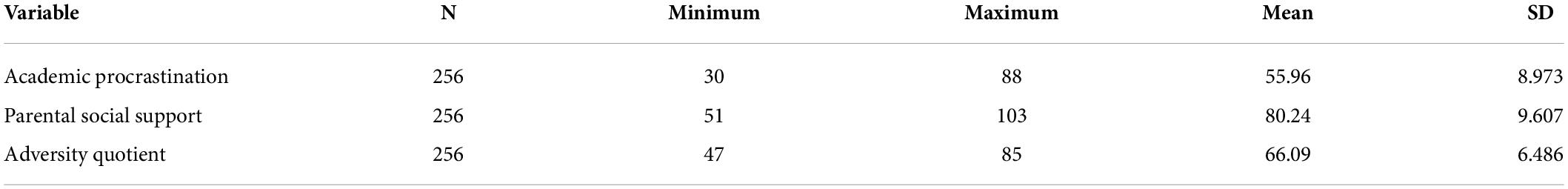

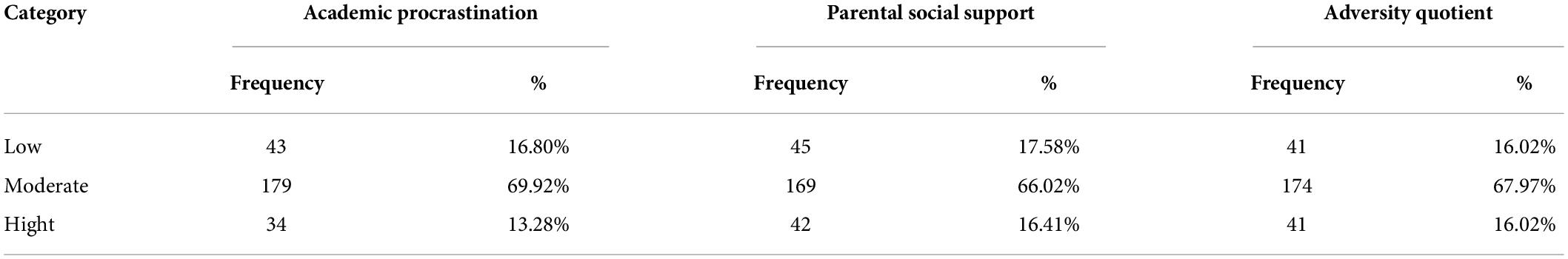

This research showed that academic procrastination, parental social support, and adversity quotient scores were within the 30–88, 51–103, and 47–85 ranges, respectively. Based on the mean scores and frequency distributions of the variables, most of the participants engaged in a medium level of academic procrastination (69.92%), perceived a medium level of parental social support (66.02%), and had an adversity quotient at the medium level (67.97%). The descriptive data of the variables are provided in Table 1, and the frequency distributions of the variables are presented in Table 2. Following the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test score and p ≥ 0.05, the data in this study were normally distributed. The academic Procrastination showed a Kolmogorov – Smirnov value of 1.17 with p = 0.129. Parental social support showed a Kolmogorov – Smirnov score of 1.072 with p = 0.2. Adversity quotient showed a Kolmogorov – Smirnov of.957 with p = 0.319.

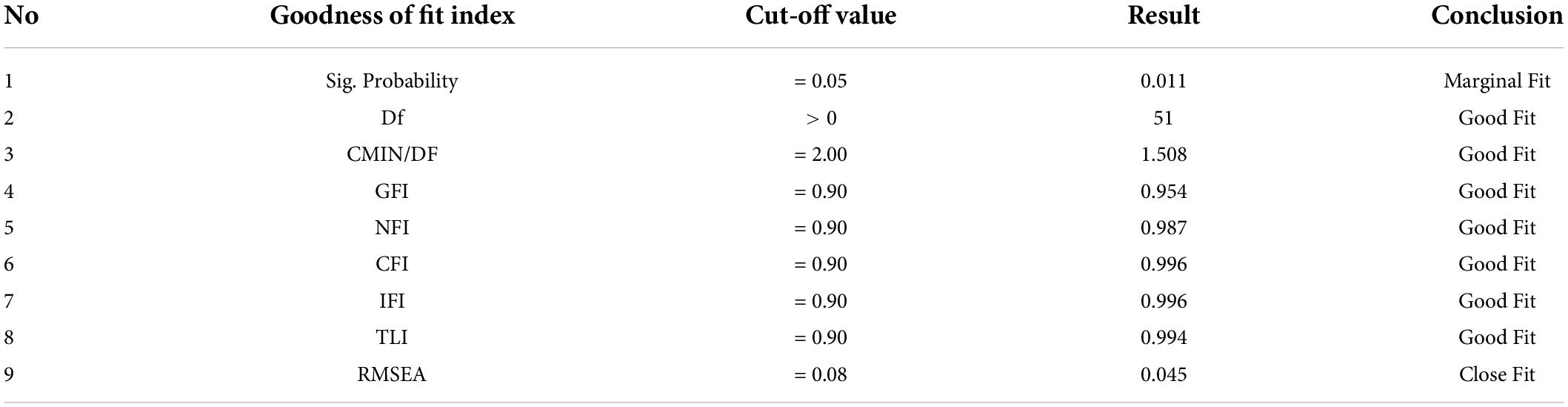

Goodness of fit

The overall model fit is presented in Table 3. Based on Table 3, the Goodness of Fit index showed good fit according to DF, CMIN/DF, GFI, NFI, IFI, and TLI and close fit according to RMSEA. Meanwhile, the sig. Probability demonstrated marginal fit, which was still acceptable. Therefore, the model goodness of fit assumption used in this research was accepted.

Hypotheses test

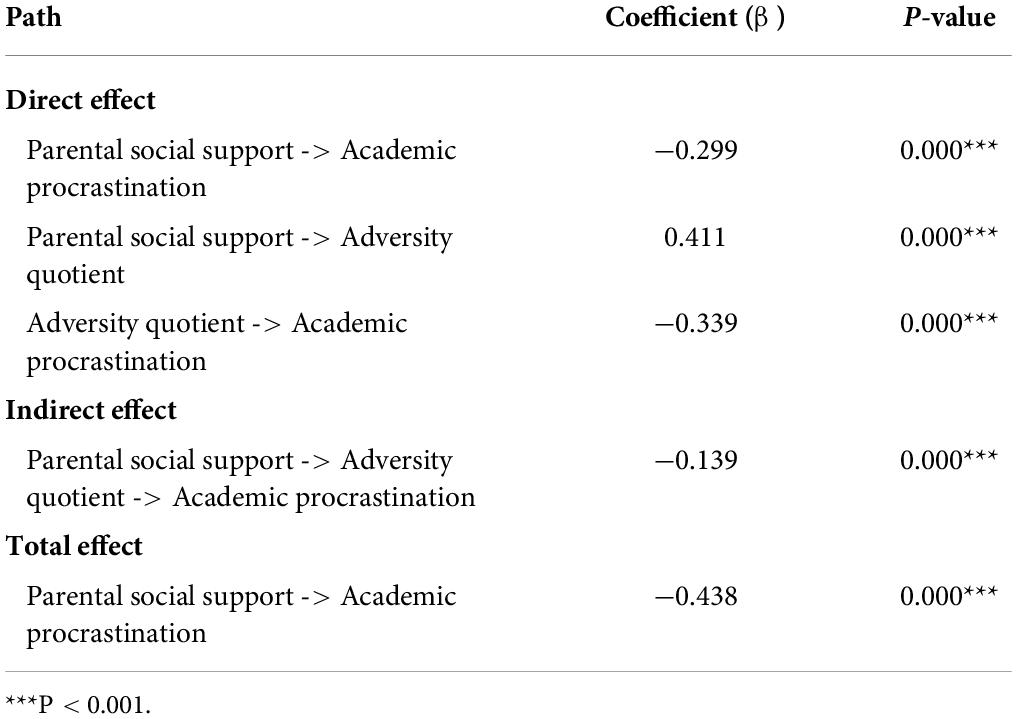

The hypotheses were tested to determine whether parental social support had a direct effect on academic procrastination or whether it had an indirect effect after mediation by adversity quotient. The analysis results are shown in Table 4 and Figure 2. The findings revealed that parental social support had a significant negative role in academic procrastination (β = −0.299; p < 0.01), parental social support had a significant positive role in adversity quotient (β = 0.411; p < 0.01), adversity quotient had a significant negative role in academic procrastination (β = −0.339; p < 0.01), and adversity quotient had a mediating role in the relationship between parental social support and academic procrastination (β = −0.139; p < 0.01). Parental social support had a greater role in academic procrastination after mediation by adversity quotient (β = −0.438; p < 0.01).

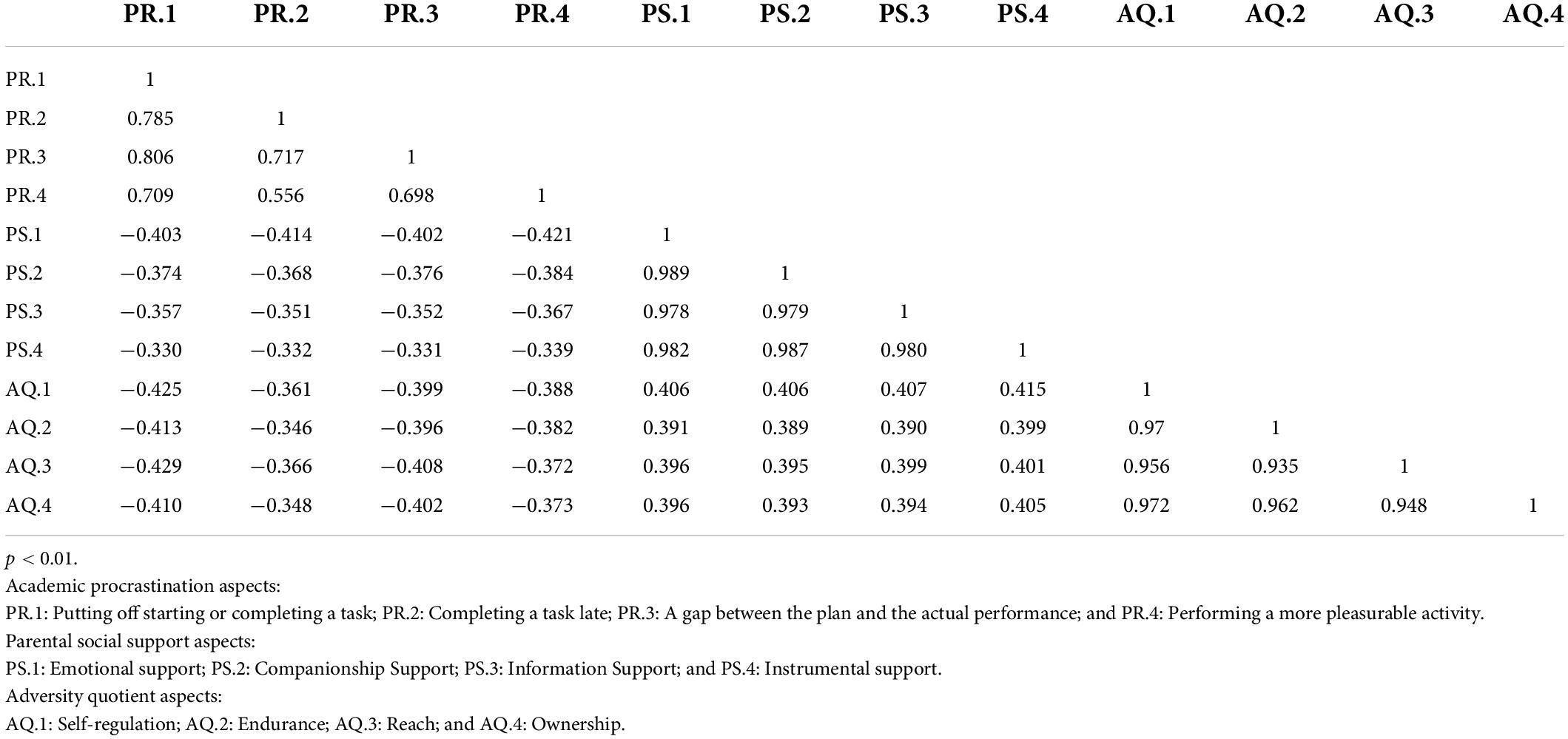

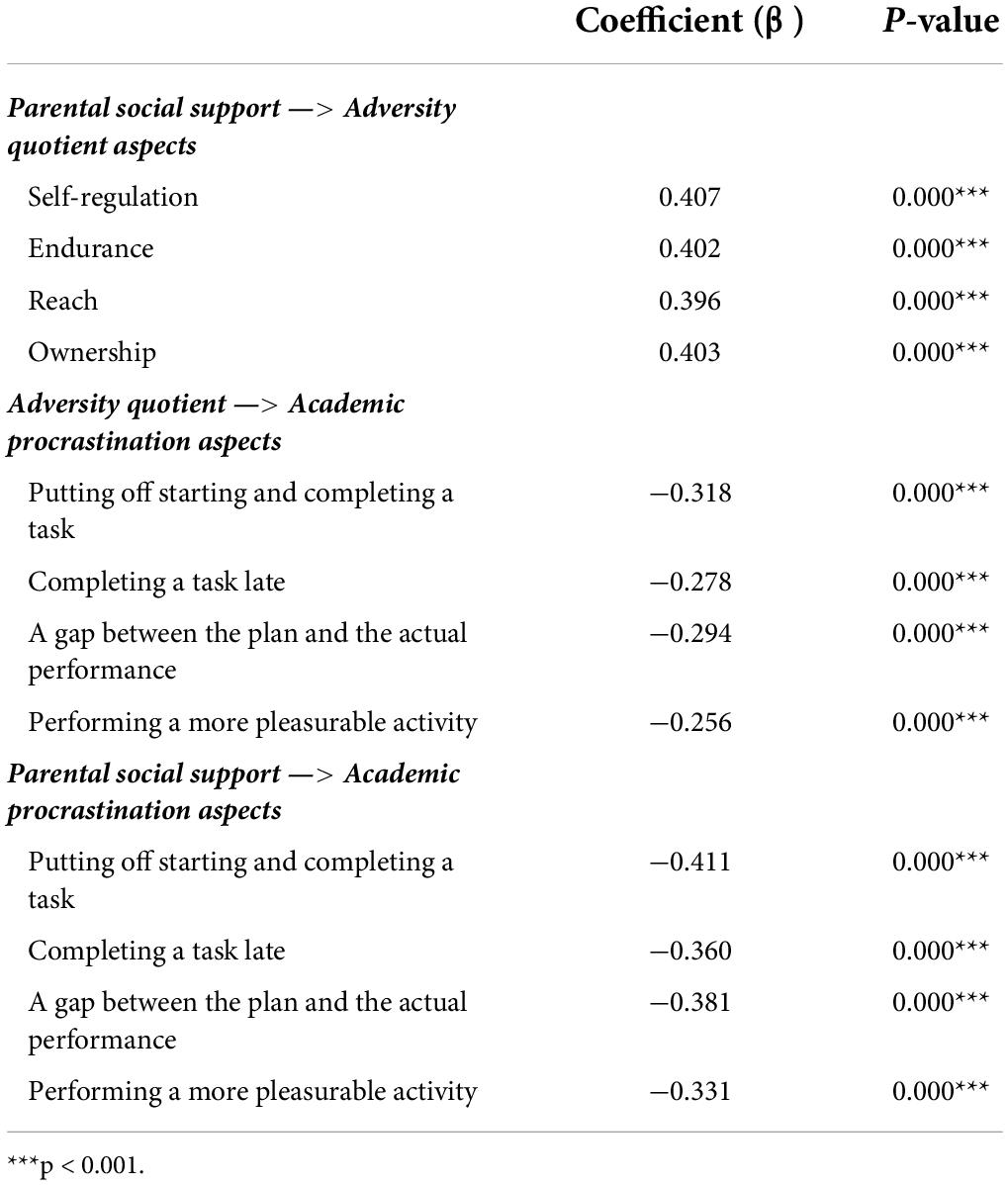

This research also showed that every variable aspect had a significant correlation (p < 0.01), as seen in Table 5. Parental social support had a significant positive role in each adversity quotient aspect and a significant negative role in each academic procrastination aspect. In contrast, the adversity quotient negatively affected all academic procrastination aspects. Parental social support had the greatest role in the control aspect of the adversity quotient. Parental social support and adversity quotient had the greatest roles in academic procrastination: “putting off starting and completing a task” and “a gap between the plan and the actual performance.” The regression test results on the variables’ aspects can be seen in Table 6.

Discussion

This research demonstrated that most Madrasah Aliyah participants engaged in academic procrastination during online learning in the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, previous research found that academic procrastination among state Madrasah Aliyah students in Bengkulu fell into the high category due to minimum knowledge and skills for using learning media, difficulties participating in online learning because of Internet access issues, and, in the case of delays in assignment submission, poor understanding of the materials and concepts delivered by the teacher during online learning (Buana et al., 2022). This gap might be attributable to the demographic aspect related to Internet access. As reported by UNICEF, only 54.49% of households in Bengkulu Province had Internet access, while in Central Java Province, of which Magelang is part, the figure was 66.73% (UNICEF, 2020). The previously reported limitations in access to affordable Internet services and suitable digital devices have caused it difficult for the larger portion of students to participate in the online learning process (UNICEF, 2020).

These findings were in line with previous studies conducted on SMA and SMK students in the same province this research was conducted, which reported medium levels of academic procrastination (Latipah et al., 2021; Habibi et al., 2022). This portrays that the greater curricular burden borne by MA students than by their SMA and SMK peers in Central Java did not necessarily make the former procrastinate to a greater degree than the latter. A further investigation concerning this matter is thus needed since other factors may also influence it.

The next finding was that most of the students perceived their parents’ support to be within the moderate category, suggesting that parental social support for MA students in implementing online learning was fair food. These findings align with previous research, which reported a moderate level of parental social support after an increase from when learning was conducted face-to-face (Wray-Lake et al., 2022). It was also found that most students had a moderate level of adversity quotient and that many were even found to demonstrate a high level of adversity quotient. This depicts that students had a fairly good adversity quotient (Wray-Lake et al., 2022).

This research revealed that parental social support had a negative role in academic procrastination. This explains that the better the parental social support perceived by the students, the lower the academic procrastination. Contrarily, the lower the parental social support was in the students’ perception, the higher the academic procrastination level. Pre-pandemic research supported this finding, stating that parental social support could suppress academic procrastination behavior (Erzen and Çikrıkci, 2018). This means that both during and before the COVID-19 pandemic, parental social support played a role in academic procrastination. This result also confirmed that parents held a key role in students’ learning process, particularly during COVID-19 (Wray-Lake et al., 2022).

Every aspect of academic procrastination, parental social support, and adversity quotient also demonstrated correlation. Parental social support contributed negatively to all academic procrastination aspects. Parental social support, particularly instrumental support, had the most significant role in the delay in starting or completing a task. Instrumental support refers to providing financial aid, material resources, or necessary services (Murray et al., 2016). The results showed that support in financial aids, devices, and services helped students suppress the rate at which they put off starting and completing a task. This is because, during the online learning process, students need parental social support for smooth learning in terms of material (money to buy Internet quotas), device (laptop or personal computer), and home condition (a conducive environment for learning) (Maqableh and Alia, 2021).

In addition, parental social support was also found to positively contribute to the adversity quotient. This explains that the better the parental social support perceived by students, the higher the adversity quotient, and vice versa. This finding is in parallel with the finding of the qualitative study by Hidayati and Taufik (2020), according to which the social support from the family served as an additional factor in the adversity quotient. It was also supported by another study on first-year students, according to which parental social support had a role in forming the ability to cope with academic obstacles during COVID-19 (Sihotang and Nugraha, 2021). Parental social support promotes students’ adaptive and constructive responses to academic challenges field (Sihotang and Nugraha, 2021). Results of a literature review revealed that the support and encouragement from parents in the forms of praises for the child’s performance, progress, and efforts, attention to the child’s self and their school performance, and provision of a conducive environment and materials for the child’s learning predicted the child’s academic achievements (Boonk et al., 2018).

According to this study, parental social support had the most considerable contribution to the control aspect of the adversity quotient. This shows that senior high school students still needed parents’ aid in positively controlling their responses to coping with online learning difficulties. Senior high school students are adolescents with a higher degree of independence than in the previous phases and with a need for self-autonomy (Branje et al., 2021). However, this aspect is still in a developmental stage and thus requires support from parents who serve as the primary support system for these senior high school students (Kagitcibasi, 2013). As stated previously, this research also discovered that all parental social support aspects, namely emotional support, companionship support, information support, and instrumental support, were positively correlated with this control aspect of the adversity quotient, with the last of the four demonstrating the highest degree of correlation. This shows that the fulfilling facilities aided students in controlling their constructive responses to online learning difficulties. Previous research stated that students experienced hardships during online learning due to non-conducive home environments, bad Internet connections, and financial burden for purchasing Internet quotas (Amir et al., 2020; Prasetyanto et al., 2022)

The further finding indicated that the adversity quotient negatively contributed to academic procrastination. The higher the adversity quotient of the student, the lower the academic procrastination, and the lower the adversity quotient, the higher the academic procrastination. In other words, the adversity quotient helped students respond to difficulties in online learning positively, hence minimizing academic procrastination behavior. This finding supported earlier research on 218 state Madrasah Aliyah students in Pontianak, Indonesia, according to which adversity quotient influenced students’ adaptability from offline to online learning, including in terms of the ability to access and use online learning to establish a learning standard (Safi’i et al., 2021). Students with a higher adversity quotient found it easier to deal with any problems (Parvathy and Praseeda, 2014). It was also in line with the results by Tuasikal et al. (2019), which reported that the adversity quotient had a negative relationship with academic procrastination in students before the COVID-19 pandemic. This explains that the adversity quotient suppresses academic procrastination behavior in students of senior high school or higher educational levels during or before COVID-19.

Adversity quotient was found to have the highest contribution to students’ putting off the start and completion of a task. Students with good adversity have a positive perception as they regard difficulties as opportunities (Stoltz, 2006). On the other hand, negative perception in handling tasks will cause students to be inclined toward delaying task completion (Pollack and Herres, 2020). Therefore, the adversity quotient reduces the tendency to put off starting or completing a task. In addition, the reach aspect of the adversity quotient exhibited the strongest correlation with postponing the start or completion of a task. Students with high adversity quotient had reached their problem limits in the event they faced (Stoltz, 2006). They make improvements across various aspects to prevent the problem from affecting other aspects (Juwita and Usodo, 2020). This explains that students who focus on overcoming learning difficulties to minimize academic procrastination tend not to cause any other problems. As discovered in previous works, academic procrastination that is left unresolved may lead to other problems, such as low final grades (Kljajic and Gaudreau, 2018) low learning dedication, low learning performance, and outcomes (Tian et al., 2021), and decreased life satisfaction and increased psychological stress (Peixoto et al., 2021).

This research also demonstrated that the adversity quotient mediates the relationship between parental social support and academic procrastination. This means that students’ ability to cope with difficulties could be enhanced by parental social support when they have a high adversity quotient, hence showing a low tendency for academic procrastination. Based on these findings, in conjunction with the existing literature, it is fair to say that parental social support drives the decline in academic procrastination (Erzen and Çikrıkci, 2018) and, at the same time, contribute to the rise in the adversity quotient (Hidayati and Taufik, 2020; Sihotang and Nugraha, 2021). Furthermore, the adversity quotient has a role in students’ tendency to engage in academic procrastination (Parvathy and Praseeda, 2014; Safi’i et al., 2021).

The results presented above have several important implications. They contribute to the literature on COVID-19 impacts on students’ academic aspects and supporting factors. It was revealed that parental social support affected academic procrastination and adversity quotient. Therefore, it is deemed necessary to pay special attention to the COVID-19 impact on parents, allowing them to provide support for their children optimally. In addition, there were also results showing that the adversity quotient contributed to the relationship between parental social support and academic procrastination. These findings have a key contribution to the academic procrastination literature, given that studies that use adversity quotient as a mediator have thus far been minimal.

This research came with several limitations. Uneven distribution of education facilities throughout Indonesia might have influenced the research results. This study was convened only to subjects in Magelang, and Madrasah Aliyah students in that. Future studies may be conducted at international schools and with the involvement of subjects in a wider area in Indonesia. Other internal and external factors may be examined in greater depth in future works since this study was restricted only to parental social support and adversity quotient. Moreover, descriptive data of parents’ situations (e.g., occupation, educational status, and income) had yet to be revealed in this research. Hopefully, future research may explain these data.

Conclusion

This study found that parental social support negatively contributed to academic procrastination and adversity. Meanwhile, the adversity quotient negatively contributed to academic procrastination and mediated the relationship between parental social support and academic procrastination. This research also discovered that each aspect of the variables demonstrated a significant correlation. Finally, both parental social support and adversity quotient could negatively predict every aspect of academic procrastination.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat Universitas Ahmad Dahlan. Written informed consent from the participants or their legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AM: conceptualization and writing—initial draft preparation. AM, NR, and FO: data curation. MM, ZM, NR, and FO: formal analysis. AM, MM, and ZM: investigation and validation. AM, MM, ZM, and NR: methodology. NR and FO: visualization. AM, MM, ZM, NR, and FO: writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Universitas Ahmad Dahlan professorship candidate research grant and Ahmad Dahlan University number 105 of 2022.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our gratitude to Ahmad Dahlan University for supporting and funding this work under the supported professorship candidate research grant.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alam, M. M., Fawzi, A. M., Islam, M. M., and Said, J. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on national security issues: Indonesia as a case study. Secur. J. doi: 10.1057/s41284-021-00314-1

Alawiyah, F. (2014). Pendidikan madrasah di Indonesia. Aspirasi 5, 51–58. doi: 10.46807/aspirasi.v5i1.449

Amir, L. R., Tanti, I., Maharani, D. A., Wimardhani, Y. S., Julia, V., Sulijaya, B., et al. (2020). Student perspective of classroom and distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic in the undergraduate dental study program Universitas Indonesia. BMC Med. Educ. 20:392. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02312-0

Anindyajati, G., Wiguna, T., Murtani, B. J., Christian, H., Wigantara, N. A., Putra, A. A., et al. (2021). Anxiety and its associated factors during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Front. Psychiatry 12:634585. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.634585

Benner, A. D., Boyle, A. E., and Sadler, S. (2016). Parental involvement and adolescents’ educational success: the roles of prior achievement and socioeconomic status. J. Youth Adolesc. 45, 1053–1064. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0431-4

Boonk, L., Gijselaers, H. J. M., Ritzen, H., and Brand-Gruwel, S. (2018). A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educ. Res. Rev. 24, 10–30. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.001

Branje, S., de Moor, E. L., Spitzer, J., and Becht, A. I. (2021). Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: a decade in review. J. Res. Adolesc. 31, 908–927. doi: 10.1111/jora.12678

Buana, A., Dharmayana, I. W., and Sholihah, A. (2022). Hubungan efikasi diri dan kecerdasan emosional dengan prokrastinasi akademik siswa dalam pembelajaran daring pada pandemi Covid-19 di Madrasah Aliyah Negeri (MAN) Kota Bengkulu. Consilia 5, 77–88.

Erzen, E., and Çikrıkci, Ö. (2018). The role of school attachment and parental social support in academic procrastination. Turk. J. Teach. Educ. 7, 17–27.

Ferrari, J. R., Johnson, J. L., and McCown, W. G. (1995). Procrastination and Task Avoidance: Theory, Research, and Treatment. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Garbe, A., Ogurlu, U., Logan, N., and Cook, P. (2020). COVID-19 and remote learning: experiences of parents with children during the pandemic. Am. J. Qual. Res. 4, 45–65. doi: 10.29333/ajqr/8471

Goroshit, M. (2018). Academic procrastination and academic performance: an initial basis for intervention. J. Prev. Interv. Commun. 46, 131–142. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2016.1198157

Habibi, N., Hariastuti, R., and Rusijono, R. (2022). “High school students’ self-regulated learning and academic procrastination level in blended learning model: a correlation analysis,” in Proceedings of the Eighth Southeast Asia Design Research (SEA-DR) & the Second Science, Technology, Education, Arts, Culture, and Humanity (STEACH) International Conference (SEADR-STEACH 2021), (Hong Kong: Atlantis Press), 311–316.

Hidayati, I. A., and Taufik, T. (2020). Adversity quotient of outstanding students with limited conditions. Indigenous 5, 195–206. doi: 10.23917/indigenous.v5i2.10823

Ikeda, M., and Echazarra, A. (2021). How Socio-Economics Plays into Students Learning on Their Own: Clues to COVID-19 Learning Losses. Paris: OECD. doi: 10.1787/2417eaa1-en

Irawan, A. N., and Widyastuti, W. (2022). The relationship between emotion regulation and academic procrastination in students of vocation high school. Acad. Open 6, 6–11. doi: 10.21070/ACOPEN.6.2022.2538

Juwita, H. R., and Usodo, B. (2020). The role of adversity quotient in the field of education: a review of the literature on educational development.. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 6, 507–515. doi: 10.12973/ijem.6.3.507

Kagitcibasi, C. (2013). Adolescent autonomy-relatedness and the family in cultural context: what is optimal? J. Res. Adolesc. 23, 223–235. doi: 10.1111/jora.12041

Kaligis, F., Indraswari, M. T., and Ismail, R. I. (2020). Stress during COVID-19 pandemic: mental health condition in Indonesia. Med. J. Indonesia 29, 436–441. doi: 10.13181/mji.bc.204640

Kementerian Agama (2022). Rekapitulasi data pokok Pendidikan Islam. Available online at: http://emispendis.kemenag.go.id/dashboard/?smt=20202 (accessed March 24, 2022).

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Kljajic, K., and Gaudreau, P. (2018). Does it matter if students procrastinate more in some courses than in others? A multilevel perspective on procrastination and academic achievement. Learn. Instr. 58, 193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.06.005

Klootwijk, C. L. T., Koele, I. J., van Hoorn, J., Güroðlu, B., and van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. K. (2021). Parental support and positive mood buffer adolescents’ academic motivation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Adolesc. 31, 780–795. doi: 10.1111/jora.12660

Laia, B., Zagoto, S. F. L., Fau, Y. T. V., Duha, A., Telaumbanua, K., and Ziraluo, M. (2022). Prokrastinasi akademik siswa SMA Negeri di kabupaten Nias Selatan. J. Ilmiah Aquinas 5, 162–168.

Latipah, E., Adi, H. C., and Insani, F. D. (2021). Academic procrastination of high school students during the covid-19 pandemic: review from self-regulated learning and the intensity of social media. Dinamika Ilmu 21, 293–308. doi: 10.21093/di.v21i2.3444

Maqableh, M., and Alia, M. (2021). Evaluation online learning of undergraduate students under lockdown amidst COVID-19 Pandemic: the online learning experience and students’ satisfaction. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 128:106160. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106160

Mohalik, P. R., and Sahoo, S. (2020). E-readiness and perception of student teachers’ towards online learning in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic. SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3666914

Murray, C., Kosty, D., and Hauser-McLean, K. (2016). Social support and attachment to teachers: relative importance and specificity among low-income children and youth of color. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 34, 119–135. doi: 10.1177/0734282915592537

Parvathy, U., and Praseeda, M. (2014). Relationship between adversity quotient and academic problems among student teachers. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 19, 23–26. doi: 10.9790/0837-191172326

Peixoto, E. M., Pallini, A. C., Vallerand, R. J., Rahimi, S., and Silva, M. V. (2021). The role of passion for studies on academic procrastination and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 24, 877–893. doi: 10.1007/s11218-021-09636-9

Pelikan, E. R., Lüftenegger, M., Holzer, J., Korlat, S., Spiel, C., Schober, B., et al. (2021). Learning during COVID-19: the role of self-regulated learning, motivation, and procrastination for perceived competence. Z. Erziehungswiss. 24, 393–418. doi: 10.1007/s11618-021-01002-x

Pollack, S., and Herres, J. (2020). Prior day negative affect influences current day procrastination: a lagged daily diary analysis. Anxiety Stress Coping 33, 165–175. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2020.1722573

Prasetyanto, D., Rizki, M., and Sunitiyoso, Y. (2022). Online learning participation intention after COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia: do students still make trips for online class? Sustainability 14:1982. doi: 10.3390/su14041982

Putri, S. N. (2020). Studi komparasi antara lembaga madrasah dan non madrasah tingkat menengah atas di kudus (studi kasus di MA Nu Miftahul Falah dan SMK NU Miftahul Falah). Attadib J. Pendidikan Agama Islam 1, 71–90.

Safi’i, A., Muttaqin, I., Hamzah, N., Chotimah, C., Junaris, I., and Rifa’i, M. K. (2021). The effect of the adversity quotient on student performance, student learning autonomy and student achievement in the COVID-19 pandemic era: evidence from Indonesia. Heliyon 7:e08510. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08510

Sarafino, E. P., and Smith, T. W. (2014). Health Psychology: Biopsychosocial Interactions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Sihotang, A. F., and Nugraha, S. P. (2021). Academic buoyancy for new students during the Covid-19 pandemic. Proc. Inter Islam. Univ. Conf. Psychol. 1, 1–6. doi: 10.21070/IIUCP.V1I1.594

Steel, P., and Klingsieck, K. B. (2016). Academic procrastination: psychological antecedents revisited. Aust. Psychol. 51, 36–46. doi: 10.1111/ap.12173

Stoltz, P. G. (2006). Faktor Penting Dalam Meraih Sukses: Adversity Quotient Mengubah Hambatan Menjadi Peluang. Jakarta: Grasindo.

Suhardi, D. (2019). Indonesia educational statistics in brief 2018/2019 Ministry of Education and Culture. Jakarta: Sekretariat Jenderal.

Susilowati, E., and Azzasyofia, M. (2020). The parents stress level in facing children study from home in the early of covid-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Int. J. Sci. Soc. 2, 1–12. doi: 10.54783/ijsoc.v2i3.117

Tezer, M., Ulgener, P., Minalay, H., Ture, A., Tugutlu, U., and Harper, M. G. (2020). Examining the relationship between academic procrastination behaviours and problematic Internet usage of high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Glob. J. Guid. Couns. Sch. Curr. Perspect. 10, 142–156. doi: 10.18844/gjgc.v10i3.5549

Thorell, L. B., Skoglund, C., de la Peña, A. G., Baeyens, D., Fuermaier, A. B. M., Groom, M. J., et al. (2021). Parental experiences of homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: differences between seven European countries and between children with and without mental health conditions. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 31, 649–661. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01706-1

Tian, J., Zhao, J. Y., Xu, J. M., Li, Q. I., Sun, T., Zhao, C. X., et al. (2021). Mobile phone addiction and academic procrastination negatively impact academic achievement among chinese medical students. Front. Psychol. 12:758303. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.758303

Tuasikal, R. F., Rumahlewang, E., and Tutupary, V. (2019). The relationship of quotient adversity with academic procrastination student counseling guidance program Universitas Pattimura.. Int. J. Educ. Inf. Technol. Others 2, 81–88. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3384324

UNICEF (2020). Situational Analysis on Digital Learning Landscape in Indonesia. New York, NY: UNICEF.

Wiguna, T., Anindyajati, G., Kaligis, F., Ismail, R. I., Minayati, K., Hanafi, E., et al. (2020). Brief research report on adolescent mental well-being and school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Front. Psychiatry 11:598756. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.598756

Won, S., and Yu, S. L. (2018). Relations of perceived parental autonomy support and control with adolescents academic time management and procrastination. Learn. Individ. Differ. 61, 205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2017.12.001

Wray-Lake, L., Wilf, S., Kwan, J. Y., and Oosterhoff, B. (2022). Adolescence during a pandemic: examining US adolescents time use and family and peer relationships during COVID-19. Youth 2, 80–97. doi: 10.3390/youth2010007

Wulandari, I., Fatimah, S., and Suherman, M. M. (2021). Gambaran Faktor penyebab prokrastinasi akademik siswa sma kelas XI SMAN 1 Batujajar dimasa Pandemi Covid-19. Fokus 4, 200–212.

Keywords: adversity quotient (AQ), academic procrastination, COVID-19, school education, parental social support

Citation: Muarifah A, Rofiah NH, Mujidin M, Mohamad ZS and Oktaviani F (2022) Students’ academic procrastination during the COVID-19 pandemic: How does adversity quotient mediate parental social support? Front. Educ. 7:961820. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.961820

Received: 05 June 2022; Accepted: 04 July 2022;

Published: 04 August 2022.

Edited by:

Roberto Burro, University of Verona, ItalyReviewed by:

Boshra Arnout, King Khalid University, Saudi ArabiaNetty Merdiaty, Universitas Bhayangkara Jakarta Raya, Indonesia

Copyright © 2022 Muarifah, Rofiah, Mujidin, Mohamad and Oktaviani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alif Muarifah, alif.muarifah@pgpaud.uad.ac.id

Alif Muarifah

Alif Muarifah Nurul Hidayati Rofiah

Nurul Hidayati Rofiah Mujidin Mujidin

Mujidin Mujidin Zhooriyati Sehu Mohamad

Zhooriyati Sehu Mohamad Fitriana Oktaviani

Fitriana Oktaviani