1. Introduction

This study asks, across the global COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, how can a sizeable business like the digital marketing firm DUK, re-adjust its business when its traditional client markets change, and then emerge in a sustainable competitive business position?

On 31 December 2019, China reported a novel coronavirus to the World Health Organisation. On 11 February 2020, this disease was named COVID-19. By 26 February 2020, COVID-19 had been detected on all continents, except for Antarctica [

1].

On 21 March 2020, the emerging global COVID-19 health crisis led the Australian Government to close its borders. On returning to Australia from overseas, inbound citizens then moved through a 14-day testing and isolation period before re-integrating back into the Australian community. During February–June 2020, Australian citizens and all non-permanent residents were instructed to socially distance. Those who were not working in essential industries were instructed to stay at home, and to avoid attending mass-gathering locations—such as sports venues, theatres, gyms, shopping centres, and restaurants [

2]. Interstate travel was restricted and most State and Territory borders were closed.

This restrictive Australian Government COVID-19 response, in effect, closed down the Nation’s social venues, closed contact events, stopped sports activities, and moved much of the business workforce into working from home environments. It then forced around 10% of the Nation’s workforce into unemployment, and placed nearly 40% of the workforce into a government supported ‘JobKeeper’ restrictive work role. This process extended into much of the business sector resulting in around one million businesses effectively being placed into a hibernation state that is expected to last for up to six months [

2]. This has created considerable economic damage to the Australian business sector, and it has delivered a shock-wave effect across the Australian economy.

Globally, lockdown days, monetary policy decisions and international travel restrictions have severely lowered both economic activities and major stock market indices. In contrast, the imposed international travel restrictions and higher fiscal policy spending had positively impacted economic activities, although the increasing number of confirmed coronavirus cases did not have a significant effect on the level of economic activities [

3].

The Australian Government directed business hibernation, and restricted human movement beyond the home, along with contact restrictions with any persons beyond the household, all of which have slowed sales, affected profits, slowed services, almost stopped marketing, slowed manufacturing, stopped tourism, stopped shopping centre retailing, and minimised non-essential business operations. This Australian Government COVID-19 response has also stopped many services and businesses from operating. These decisions in total have left over 15% of the workforce unemployed, and with little new work opportunities available, some people are now reporting ancillary health and mental issues [

2].

The Australian COVID-19 economic impact is likely to surpass 15% of GDP, with government expenditure exceeding

$300 billion to offset losses to the workforce, consumption, and investment [

4]. Into the future, and after COVID-19, Australia as a nation is likely to pursue the rebuilding of its economy, and this may also encompass significant changes in societal perspectives [

5]. Against the ongoing COVID-19 background, how does a business survive in Australia when its traditional client markets change, and post COVID-19, how does it then emerge as a sustainable competitive business?

1.1. Strategic and Theoretical Underpinning of a Firm’s Sustainable Competitive Business

Theory delivering a sustainable competitive business remains inconsistent. In part, this is because a firm’s business can encompass a diversity of activities. A firm typically adopts a strategic management process. This likely encompasses a ‘resource-based view’ of the firm, plus theoretical extensions encompassing business expert systems, knowledge development/utilisation capabilities, and delivering sustainable (competitive) business advantage [

6]. This theoretical resource-based view also captures strategies [

7], competencies [

8], business innovation [

9], economic worth [

10], product development [

11], and research implications [

12].

However, several other strategic management approaches may exist beyond the resource-based (internal) view and its superior heterogeneous firm returns [

13,

14,

15]. For example the ‘industry-structure’ (external) view focuses on superior returns [

14,

16,

17], the ‘competence-based’ view efficiently uses resources [

18], the ‘knowledge-based’ view engages knowledge as a key productive resource [

19], and the ‘relational’ view encompasses and extends the above alternate approaches— by enlisting cooperative strategy placements, by interlinking bi-directional networks, and by building of intra-organisational and inter-organisational competitive advantage [

20]. The ‘relational’ view of the firm also adds dynamic data to the business and its external environments [

21], and it is most applicable to the firm’s strategic management domain.

The build of a sustainable competitive business also fits within institutional theory as talent-resourced firms enlist their workforces to target the competitive advantage that can arise between the firm and its upstream and downstream partners [

22].

Thus, a firm combines its competencies and its intellectual data analytics into a relational system designed to deliver its capabilities, resources and its deliverables, whilst producing an ongoing competitive advantage position [

23,

24]. When competitive advantage is associated with an improved economic performance [

25], the firm can achieve further competitiveness. Transaction cost economics theory [

26], social capital theory, and organisational learning theory can also help the firm build strategic business solutions within its surrounding competitive environment [

26].

However, a firm’s strategic management even extends into behavioural theory. Here, the theory of planned behaviour [

27], motivation theories [

28], consumption theory [

29], and users-gratification theory [

30], can also help it build consumer-targeted solutions that ultimately contribute to its competitiveness. Such behavioural theories support the position and time-lined relational sequential flow of

Figure 1’s 3Cs Framework blocks.

Figure 1’s 3Cs embody a resource transference relationship. This occurs relationally, sequentially, and over time. Hence it is causal—from competencies to capabilities, to competitiveness. As a causal structure, it can enlist construct items—measured against a Likert scale framework. The model’s causal flows both within (and between) the constructs (and their item measures), and the relationally-mapped causality can be mapped against Hume’s theory of causation and Aristotle’s 4-step theory of causation [

31] (material-cause—construct literature-defined and with relevant literature-supported measurement items; then formal-cause—measurement items construct-linked, and typologically grouped; then efficient-cause—data capturing ‘best’ representation of each construct; and then final-cause—constructs jointly modelled as a statistically relevant business solution).

Thus, the firm strategically and collectively encompasses a broad spectrum of theories. However, it does fit within the strategic management relational view of the firm, and consequently fits within the strategic management paradigm. The above section also sets the theoretical framework for the building of a strategic 3Cs Market Intelligence Framework (

Figure 2)—one that is likely adept at delivering dynamic, inter-firm competitive advantage [

20,

21,

32].

1.2. The Digital Marketing Company DUK

In Sydney, Australia, a leading and technologies-agile, digital marketing firm trading as ‘DUK Agency P/L’ encountered a rapid reduction in the economic activities of many of its major clients. In just a few weeks, many of DUK’s major clients either massively reduced or even stopped trading. This situation arose because the government, as a response to COVID-19, had closed this section of the economy, or because they were now in a situation, where, with consumer movement restricted, they had little to trade. Some of DUK’s major clients who could stay operational continued their marketing and some even monopolised their markets.

Many of DUK’s smaller business clients soon found that the COVID-19 and government-induced business downturn situation had left them in an unsustainable economic situation. Thus, DUK’s smaller clients also downgraded, or stopped their marketing and advertising spending. Hence, a long-term, and solid firm revenue stream—that easily supported over 30 high-skilled, lead marketers, almost vanished—with around 70% of DUK’s revenue steam disappearing across two months.

Like other marketers, DUK first used its competencies and leveraged these to apply its client’s capabilities towards generating additional physical and digital consumer reach, and subsequent sales improvements [

33]. However, DUK, unlike its competitors, operated differently when dealing with its clients. Its workforce acted as both physical and digital marketing strategists [

33,

34], and as ongoing management consultants [

35].

DUK’s client marketing involved bringing its unique, research-developed 3Cs business model approach (

Figure 1) into the contracting client’s domain. This offered a differentiated digital marketing approach—aimed beyond marketing, and towards also enhancing the contracting client’s competitiveness outcomes [

33,

36,

37]. This complex DUK marketing approach remains difficult to imitate or transfer. It strategically structures DUK into its ongoing lead marketing position. It allows DUK to follow multiple system pathways across its P1 and P2 transitions, and to closely understand its contracting client’s business. With such understanding comes the relational trust, and ability to share additional business deliverables into, or within, the client’s capabilities set. This is well beyond, but complimentary to, its normal market reach and product sales solution. This DUK–client relationship also offers a pathway towards an invigorated client competitiveness business positioning [

38].

2. DUK 3Cs Internal Strategic Marketing Approach

COVID-19 created massive revenue decline to DUK’s digital marketing and forced it to investigate all business survival options. The DUK team scoured all marketing and sales opportunities, and assessed these against its clever research and development. DUK shifted its external 3Cs strategic marketing approach with its contracted clients, and turned this approach inwards as a 3Cs strategic marketing and management consulting approach—but with DUK as its own client. It then quickly pivoted to totally new markets.

2.1. DUK’s Competencies

DUK first considered its existing competencies. Its business capacities were used to drive a clear client, firm value for money, product-focusing, high-quality product development, rapid business change, and authentic, enduring business leadership [

39]. These competencies flowed through its advanced programming, data storage, digital integration, design, research and development, content creation, social connectivities, social collaboration, animation, video, and incentiviser pathways. DUK’s ability to adapt and build creative marketing and sales strategies alongside strategic management and finance leadership have helped to make DUK one of the market leaders in the digital domain. Therefore, DUK’s in-depth talents lay within the digital domain.

DUK’s knowledge creation delivered (1) past (and stored) learned experiences, (2) knowledge-based digital infrastructures and customer practices for the client, (3) expert knowledge development, and (4) new knowledge collations for the client. DUK collated its expert knowledge developments, and its new knowledge into achieving strategic corporate and marketing results for their clients. Thus, the DUK Agency actually operated as a strategic management and marketing consultancy firm [

40]. Its ongoing knowledge creation and its supporting innovation pursuits also helped it to tap into its internal abilities to find and to build new expertise.

DUK’s digital innovation chased unique benefits, framed agility into its problem solving, chased tomorrow’s future emergent hypes, redesigned work and continually solved requests, and transformed its digital capabilities into an exponential growth driver [

41,

42]. Thus, DUK knew how to work in fast-changing environments. Hence, it sought to leverage more from its technologies, and to stay in demand. DUK then turned its attention to a Gartner Hype Cycle with future emergent positional ratings of (1) marketing and advertising, (2) emerging technologies, (3) block chain business, and (4) artificial intelligences [

43]. It assessed these possibilities as potential saleable media, and as mobile marketing media pathways beyond COVID-19.

DUK held considerable intellectual capital—both across its workforce, and stored—digitally. This enabled it to (1) build leading market reach consulting pathways, (2) improve and grow digital and social capital, (3) create world-class performance, and (4) match accessible resources to task completions. The ambidextrous nature of its intellectual capital provided it with a sustained performance [

44]. Thus, DUK was in a position to reinvent itself, and to

pivot with knowledge as required.

Next, a DUK-specific ideas generating brainstorming session was applied. Productive ideas included: service existing clients superbly with social connectivities and client–client cross-marketing; offer site(s) updating with creations such as dynamic information walls, and multiple client market reach enhancers; against less competition, use its SEO competencies to reposition clients into top of listings; apply extensive consumer tracking data to clients, etc. In-depth DUK debating also concluded that although client retention was likely, this strategy would likely generate insufficient additional revenue. However, these solutions were seen as long-term, doable, diversifying, new business and marketing pathway enablers that would enable growth and increase revenue beyond COVID-19.

2.2. DUK’s Capabilities

With the background research job part completed, DUK next turned to investigating its capabilities. DUK’s capabilities are applied systems of developed business deliverables aimed towards increased firm competitiveness. First, using its competencies, a digital shopping centre was pursued as a pivot with knowledge model capable of meeting the likely needs of current and future Australian consumers. COVID-19 had forced buying from home and had forced consumers to learn ‘new’ online shopping skills.

The digital shopping venture offered DUK an additional sustainable business, and if developed astutely, it offered a long-term competitive diversification pivot for DUK. This complex task was readily doable. It drew on DUK’s in-house programmers, its combined data systems, its business development packages, its intellectual capital/IP, and its real-time tracking and logistics systems.

DUK then built its digital shopping venture as a new mobile-targeted business system— specifically targeting real-time and connecting with the external consumer market. To frame its approach, DUK enlisted the two left-side adaption and application knowledge blocks of

Figure 1’s 3Cs. It created its necessary capabilities into internal/external networked (1) business values deliverance systems [

45], (2) risks avoidance systems [

46,

47], and (3) marketing and sales systems [

33]. These blocks are expanded in

Figure 2 but they are also specifically focused towards delivering both business sustainability and competitive intelligence advantages. Feedback loops also operate across the three blocks of DUK’s 3Cs Market Intelligence Framework as shown in

Figure 3.

2.2.1. Capabilities Investigations

DUK’s new digital shopping venture then saw it explore further business capabilities, and to seek further business externalities inclusions [

48,

49]. Hence, DUK embarked upon a global marketplace and marketspace business opportunities assessment. The workforce scanned for ideas. It looked at (1) its past marketspace leaders, (2) winners in the digital world, (3) hype cycle inventions/concepts/developments, (4) innovative products, (5) digital creations, and (6) new challenges. DUK generated a list of feasible risk assessed, and new initiatives that could be marketed. With this background, attention turned to COVID-19 and its new health-related growth of new businesses.

DUK tackled the COVID-19 health domain. It brainstormed COVID-19-related areas such as personal professional equipment (face masks/shields, goggles/glasses, gloves, gowns, head/shoe covers, full coveralls, etc.). Such contact prevention aids helped protect health workers against the transmission of the virus via direct contact, or via droplet transmission pathways. These devices required manufacturing or importing. DUK investigated this option, but it held time, production and logistic uncertainties, price fluctuations, and foreign currency exposure.

Personal checking devices (temperature detectors, testing sets, etc.), and the operational treatment requirements (ventilators, oxygen, isolation rooms/beds, etc.) also supported the above contact prevention areas. These items required local or international sourcing, and, at times, variable delivery timelines, but symptoms measurement software was possible—with appropriate DUK partnerships.

Drugs and other applicators designed to treat and overcome this virus likely required specialist trials, and lengthy approvals, as no recognised solution to COVID-19 had yet emerged from existing drugs/mixes or new formulations. This area was considered beyond DUK’s expertise.

Personal hygiene was another area of prevention (soaps, hand sanitisers, wipes, alcohol, etc.). Such manufacturing processes are in existence in Australia, so a late entry needed to have a competitive edge, and a specialist partner. Hence, further market research into this already competitive market area was deemed essential by DUK.

Waste disposal of the above items and medical treatment items was specialised and beyond DUK’s skills set, but tracking the waste was likely doable using an existing identification and tracking system. However, this likely remained as specialist peer-to-peer logistics requirements/systems (specifications, connectivities, sourcing, shipping, etc.), but these were deemed largely beyond DUK’s domain.

Many other COVID-19-related health, personnel, and aged care home options were also identified, mapped, trialed, and assessed. For example, a notifications and information wall was established and sold to aged care homes as a virtual means of ongoing contact between isolated elderly parents and their family members.

DUK also looked for inspiration. It noted that a world shortage of respirators for severely ill COVID-19 patients was leading one of the Australian V8 Supercars racing teams to pivot. It tracked this pivot approach [

50]. Here, the Triple Eight’s T8 race team engineers rapidly pivoted from intelligent car ventilation systems. They set about creating a medical respirator for COVID-19 patients. This involved the rapid design, creation, prototyping, refining and miniaturising of a unique medical ICU hospital respirator, but based on the race car’s intelligent ventilation system. This respirator was designed to be portable, complete with (1) alarms, (2) a 4G telemetry system messaging a central digital dashboard station, and (3) a simultaneous monitoring capability. This group of patients could now be monitored in real-time across multiple hospital rooms by one supervisor.

This car racing pivot with knowledge aligned to DUK’s 3Cs business leadership perspectives. It provided DUK with ongoing inspiration as it reconsidered the extent of its possible capabilities pivots and future change options.

2.2.2. Capabilities Targeting

DUK identified its target COVID-19 areas as personal professional equipment, personal hygiene, personal checking, and communications logistics. As health marketing per se was unlikely to offer sufficient revenue, the company chose to pivot with knowledge, but initially across multiple related domains. A team built logistics, tracking and digital wall connectivities software. A team pursued overseas suppliers. A team supported its few remaining clients with the latest ideas and extras. A team pivoted in pursuit of the high-profit hand sanitiser market. All teams delivered complimentary DUK business contributions.

Management chased the pivoting to hand sanitiser manufacture and sales. It approached one of its Australian distillery clients (termed herein ‘the XYZ Distillery’), and made a Joint Venture pitch. The XYZ Distillery was already profitable, but it too recognised the unique opportunity of a pivot into a higher profit sanitiser area. Both DUK and the XYZ Distillery agreed to pivot and share profits.

2.3. DUK–XYZ Distillery: Pivot into a Joint Venture

Within a few days, a Joint Venture formed, but the two companies were operational from business centres located over 1500 kms apart. Shipments of hand sanitiser from the XYZ Distillery to DUK involved a 14-hour 660 km road and sea crossing, plus road transport to Sydney. The Joint Venture then ensured all formulations adhered to WHO standards. This was a necessary legal requirement before selling any alcohol-based hand sanitiser products.

The XYZ Distillery set about the upstream manufacture of hand sanitiser (a 1–2 week process). Through research, they rapidly sourced and successfully formulated hand sanitiser products. This was followed by immediate trials and testing, and both were successful.

Alcohol production and hand sanitiser-blended product manufacture were both ramped up. Occasional large orders were supplied direct from the XYZ Distillery, but around 90% of the hand sanitiser product was shipped 1300 kms by sea and by road to Sydney in 1000 litre containers.

DUK, led by its research and development, marketing/sales innovation, and its strategic management team pursued all sanitiser production downstream business requirements. Its new transactional website, and new social sites, then pre-sold the Joint Venture’s hand sanitiser product to an Australia-wide market. The Joint Venture’s DUK digital transactions website and its associated new Joint Venture social sites logged and prioritised orders. Labels meeting approved TGA and WHO standards were designed, printed, and fixed to the sanitiser bottles. Express shipping of consumer orders was coordinated, and digitally tracked. Bulk re-bottling from 1000 litre containers to 500 mL glass bottles opened another personal consumer market and extended the hand sanitiser’s market reach.

Plastic spray bottle manufacturers in Australia could only supply large quantities in two months’ time, so overseas bottle suppliers were sought. Again, a lengthy four-week international supply time was required. To minimise time-to-market, the XYZ Distillery also shipped to Sydney 15-litre plastic drums, and pre-filled 500 mL, design-stamped glass bottles. To further expand the product range and meet a consumer small product demand, small 250 mL plastic bottles were bulk ordered. All product materials coalesced into DUK’s new shared Sydney warehousing, bottling, labelling, logistics, and shipping facility. DUK also pursued temperature devices, masks/shields, and gloves as potential additional health-related revenue streams.

Next, as supplies ramped up in Sydney, new sales avenues were tackled including: small chain, but large-sized supermarkets, schools and universities, plus large tier-1 and tier-2 building firms. Here, the competition remained fierce but DUK’s marketing skills soon found a niche. The Joint Venture found the market required a differentiated hand sanitiser solution formulation, aimed specifically at dispensing refill containers across work sites. A second substantive market lay in the industry-wide need for continual surface cleaning sanitisers. These solutions clean contactable surfaces around places where people congregate, eat, or work. These included shared spaces such as hot desks, education work/study benches, lunch rooms, toilets and meeting rooms.

The sanitiser market extended physically into shop (reseller) sales, and into market-style street stall refills/sales. Digitally, the consumer market is now recognising the Joint Venture’s hand sanitiser brand, and associating the brand with positive quality feedback and rapid operational deliveries. Hence, sales moved strongly into a reselling domain, and a new sustainable Joint Venture business was created for both participating firms.

2.4. Joint Venture Markets Extension

The Joint Venture story now extends into the hospital grade 80% alcohol-based sanitiser. This product was again pre-sold to nursing homes, and to elderly residential settlements. This successful Joint Venture remains important to both DUK and the XYZ Distillery as it provides them both a secondary business pathway beyond the COVID-19 crisis. From DUK’s perspective, the Joint Venture helped it reallocate additional work into researching its digital marketing domain, and into further assisting its remaining digital marketing business clients.

This pivoting seems simple, but many have tried this particular pivot and failed. In effect, and within a few days, both DUK, and the XYZ Distillery fully pivoted into a new business domain. The XYZ Distillery added a hand sanitiser production line. DUK transformed a section of its workforce into this new strategic business operation—encompassing digital sales, production forecasting, shipping, storage, bottling, packaging and distribution. However, it still maintained a successful, but downsized, skeleton, client-focused, digital marketing operation.

This successful Joint Venture pivot was not luck. It was mutually formulated and it built on the mutual relational trust between the two firms. It developed shared inter-firm resources. It followed a strict, structured, and latest research-modelled logical progression. This approach was aimed at delivering to both firms an ongoing additional competitiveness positioning.

2.5. The DUK Digital Shopping Markets Extension

COVID-19 restrictions meant much of the Australian population came under Government instruction to stay isolated around their homes. Today, most Australian homes are either optically, digitally, or mobile connected. Millions within the Australian workforce now fulfill their job roles remotely across the digital divide. Millions of others have quickly learned new digital ways to (1) engage, (2) digitally learn, (3) digitally communicate, (4) digitally shop, and even (5) consult with doctors via a new digital Telehealth service. Hence, the Australian market has necessarily acquired better digital skills. DUK saw this as a market ready for a new comprehensive style of virtual shopping, but at warehouse price points.

DUK pursued this new, dynamic, and large scale business opportunity. It market-targeted consumers and their requirements. It quickly built contacts, chased discounting warehouses, and tapped ‘reliable’ overseas suppliers. It then established its new ‘Amazon-style’ digital shop. Here, a consumer buys through the virtual warehouse shop front, with purchase items supplied directly from the warehouse, the manufacturer, the importer, or from offshore suppliers. This virtual shopping centre required DUK’s exemplar marketing, a substantive DUK website with the best of its web-social-mobile features, secure programming, virtual payment options, and block chain solutions. All were readily doable. DUK’s virtual warehouse shopping centre has since led it into another pivoted Joint Venture. It is now operating this new digital warehouse Joint Venture as a very different mobile warehouse distribution business.

4. Discussion

4.1. The ‘Pivot with Knowledge’ Solution

Adopting the above changes, and its business pivots with knowledge approach, DUK produced new business pathways through the COVID-19 economic downturn. All ideas and perceived opportunities were intelligently sifted, and the best ideas were attempted. The DUK workplace became a busy, research-active, competitive (in part to prevent possible job losses), creative, and innovative operations zone. As new research assessments materialised, DUK’s ‘ideas board’ continually changed. The one hour-per-week research time, transitioned in part to a daily new knowledge assessment of latest activities refinements. The workforce, as a marketing team, stayed on task, and any idle time was committed to any task that supported the firm’s ongoing competitiveness.

The programmers, designers, content developers, social connectors, proofers and programmers developed new products for the existing clients, whilst also building and trialing new pivot solutions. Team leaders worked with their clients and carefully service-managed them.

Management and finance sought cost savings and cash accounting. They tightly monitored expenses, such as advertising, marketing, purchases, printing, shipping, software, client-management systems, web and other digital sites. They minimised client payments-in-arrears, and individually assisted every existing client to retain sales.

Marketing (and sales) chased COVID-19-driven, new health and health-support businesses, and considered all DUK ideas/opportunities as potential pivots to new markets, new clients, and new consumers. This required new tactics, new data-mining, and new knowledge processing.

DUK’s programmers successfully digitally remodelled its business platform to allow further intelligent tracking and to flag workforce, client and consumer data with requirements versus deliverables. These also mapped against its 3Cs approach. This provided management with additional digital dashboard controls and with additional rapid response decision-making capabilities.

Other DUK successful pivots included its digital contact wall creations for existing clients, and integrated cross-platform video ads for web, social and mobile sites. It also created a new shipping and marketing business supplying grades of hand sanitiser and surface cleaner Australia-wide. It established a new, in-house owned and operated digital warehouse shopping centre and another digital warehouse Joint Venture. Both digital consumer-engaging sites were structured with their own unique block chain and value chain approaches—complete with social media linkages, product sales facilities, logistics distribution and Australia-wide network tracing.

4.2. Future-Proofing the Firm

In times of crisis, such as the economic decline created through the COVID-19 global pandemic, agile, on-task services firms can consider similar approaches adopted by the marketing firm DUK. These firms first draw on their 3Cs advanced future scenario mappings of their businesses. They then pursue their chosen researched business changes option. Such firms likely need to maintain a workforce that can remain agile, flexible, and possess the capacities and capabilities for rapid and directional business pivot changes.

A Sydney service industries printing firm employing 30-plus staff, recently pivoted under COVID-19 business restriction pressures, and created the online business BuildaDesk.com.au. Its desk is made of a local expandable, environmentally-friendly, plastics-free, honeycomb board. It can be assembled without tools. It is also shipped Australia-wide in 48 hours, and costs only $149. This pivot has given this printing firm a new worldwide market. Again, workforce agility, flexibility, and the ability of staff to brainstorm, innovate, and pivot with knowledge is an essential 3Cs process contributor towards maintaining business sustainability.

Producers, like the XYZ Distillery, should also remain agile and look for alternative uses of their production lines. With little adjustment, the XYZ Distillery pivoted one production line, purchased a few minor ingredients and made hand sanitiser solutions and alcohol-based surface cleaners. The XYZ Distillery should now update its 3Cs approach, and look towards a future possible production scenario. It should now ensure it retains a creative, flexible workforce, and should seek further innovative internal and external capabilities—such as further multi-purposing its production lines, and possibly adding a plastic bottle injection-molding line. They could also consider business optimisation and failure-proofing processes.

Manufacturers like the car racing team Triple Eight, who work at the leading edge of their technologies, could apply their inherent leading-edge talents, and even offer their services to new industries such as Elon Musk’s SpaceX, or again remap their talents against other hype cycle inventions in the energy conversion sector. These potential high-value, high-reach possibilities can again be framed under a 3Cs approach.

The future-proofing of the Australian firm, DUK, has strategic internal business sustainability implications. The COVID-19-induced global economic crisis has seen many astute Australian firms re-assess their competencies. This study believes such astute firms can enlist DUK’s 3Cs approach, and test exploratory business shifts and pivots with knowledge against differing business situations. This change in an environment’s approach can enhance the agility, flexibility, dynamism of firm management—leaving the firm better prepared to introduce rapid responses when required. Further, in tough economic times, and when seeking business sustainability, Australian firms can also look externally and be prepared to adapt against any changed external market conditions.

4.3. The External Solution

External business sustainability is another future-proofing component of the Australian firm. Externally, a solid starting point remains Porter’s (2008) five (external) forces [

54]. These forces, once understood, then shape a business’ internal strategy against the power of its suppliers, the threat of new market entrants, the bargaining power of its consumers/buyers, and the threat of new substitute products and/or services.

Porter’s competitive strategy [

54] approach assesses a firm, and offers long-term, planned, directional pathways, that, over time, allow it to find a degree of competitive advantage over its immediate, industry-wide, and global business rivals. This process is, in effect, a normal defensive business positional strategy. It should also be directed towards acquiring an enhanced return on investments. Thus, externalities are another strategic competitive business component to the future-proofing of an Australian firm. An additional external advantage arises when the firm has the ability to

pivot with knowledge and to direct this reposition towards enhancing its ongoing competitiveness.

Hamilton [

55] suggests this defensive and strategic external advantages approach also extends internally. Here, digital service-sector pathways can feed into the firm’s digital competitiveness, and can also expose personalised business-to-individual-consumer (B2C) engagement pathways. This again leads management to pursue new digital and actioning skills. Porter [

56] adds that the digital domain remains highly price-competitive and quickly brings rival firm challenges. Thus, digital domains are especially difficult to future-proof. Digital marketing companies like DUK should remain nimble, dynamic business developers/operators. They should also remain external, global highly-competitive performers.

4.4. The Resultant Agile ‘Pivot with Knowledge’ Solution

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 and Porter’s Five Forces model provide a base framework for the future-proofing of an agile Australian firm. Today, an agile Australian firm, capable of generating potential pivots, needs to maintain, and continually intermix, its networks of strategic leadership/management and operational systems. These firms typically show dynamic but flexible equilibrium. They are often capable of making changes on-demand as circumstances alter. In unforeseen economic crisis situations like COVID-19, these agile Australian firms can knowledgeably operate their strategic business changes against, and within, their advancing:

global and local competitiveness systems

digital business knowledge systems

innovation and technologies systems

capabilities systems

optimisations and feedback systems

economic systems

intelligences and services systems

internal/external leadership and overviews systems.

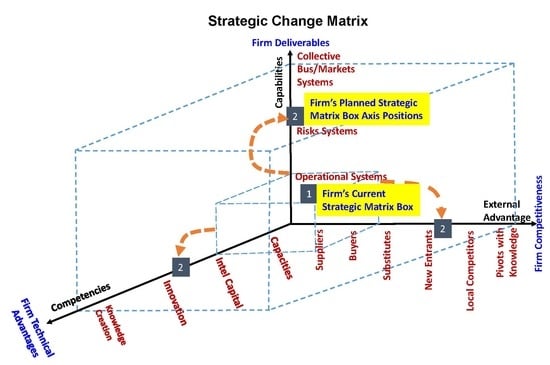

Hence a strategic systems structure is proposed where all constituent elements are activated and continually enhanced. These systems can all be portrayed within the three-dimensional strategic change matrix as shown in.

Figure 3 depicts the author’s and DUK’s strategic change matrix. DUK is a strategic marketing company operating at its chosen matrix position 2. It has developed, and continues to develop, a vast array of innovative, knowledge-creating competitive business tools. As it sources the new latest ideas, DUK assesses them, and feeds the relevant ones into its modified suite of 3Cs. This flows into DUK’s next, strategic repositioning—beyond its current strategic change matrix position 2. Thus, when dealing with clients, DUK continually modifies, improves, and grows its learning curve position.

When assisting a SME client firm who, for example, currently operates at matrix position 1, DUK can share some of its competencies to help deliver client firm capabilities changes. Consider for example, an SME client firm at position 1. It has a current strategic competitive advantage, and is operating in a secure supplier-buyer environment with minimal external competitor substitute products. This SME client firm has its business capacities well-integrated. It possesses strong intellectual capital. Its operations systems are producing profitable consumer-demanded items. In short, this SME client firm is currently well-positioned within its matrix of strategic possibilities.

However, within the strategic change matrix, DUK can assist with a multiple array of internal interlinked matrices of competencies and capabilities deliverables—ones that are likely client firm operational enablers. DUK can then strategically lead this SME client firm into changing from its existing matrix position 1 to, say ‘position 1a.’ It can assist with the installation pathways, the matrix building and the innovation processes that can likely facilitate an internal and external business repositioning into a new, expanded matrix positioning—one likely offering improved products, greater sales, more revenue, better servicing, and additional collective intelligences. This strategic change matrix approach is one that continually expands—whilst also becoming more efficient, effective and integrated.

DUK used its

Figure 3 approach when

self-pivoting with knowledge into its chosen, expanded, externally-advantageous matrix position. It used its competencies, especially its digital assets, and its agile capabilities as starting points. It add pivots to its previous strategic change matrix and so created a new dimension to its business strategy. Further internal information related to the mechanics of

Figure 3 currently remains the confidential property of DUK and its academic business researcher.

Thus,

Figure 3 embeds DUK 3Cs (its competences, its capabilities and deliverables, and its competitiveness). It offers firms new understanding concerning their ability to matrix-box position and further future-proof their business network. It can also aid an astute firm when seeking to strategically change its current matrix-box position into a more expansive, more competitive matrix-box position.

Any firm can use this 3Cs and strategic change matrix approach to strategically position themselves; they can also do this for their competitors, and so visually reinforce their points of competitive difference against their external environment. They can also make choices as to where they may wish to reposition. Their next matrix-box need not be a square or rectangular, and it may expand towards just one point or towards multiple combinations of points.

The study’s COVID-19 business cases of DUK, the XYZ Distillery, Triple Eight, and BuildaDesk indicate that as different firms, in differing industries, each firm can pivot and change the mix of their competencies, capabilities and competitiveness (3Cs). In addition, each firm can also strategically re-map itself into targeting another unique, and different strategic change matrix-box position—one that likely offers a sustainable competitive business position. XYZ Distillery possessed the infrastructure and most of the process knowledge for sanitiser manufacture, but lacked the knowledge creation, risk capabilities, and marketing, so it joint ventured with DUK. Triple Eight and BuildaDesk each created entirely new extension businesses, and so recreated, extended and repositioned their existing strategic change matrix-box.

Further, firms responding to any global business crisis can use their combined 3Cs and strategic change matrix approach. Firm ‘A’ can strategically choose to establish a new, expanded, competitive, matrix-box position. Firm ‘B’ can strategically use a targeted diversification strategy to target a different matrix-box repositioning. Firm ‘C’ can strategically choose to hold its current matrix-box position by strengthening its current business deliverables.

Thus, the 3Cs and strategic change matrix approach visualises multiple strength, or expansion, or diversification, matrix-box position options. Each option can be strategically assessed by the firm. Then, one chosen, unique business solution to the one global business crisis can be decisively pursued.

5. Conclusions

Across the global COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, the digital marketing firm DUK, used its 3Cs model, and its strategic change matrix to re-adjust its business when its traditional client markets changed, and to re-map its emergence into a sustainable competitive business position.

DUK recognised its consumer market had changed due to COVID-19. It pivoted with knowledge, and it morphed into an ‘optimised’ digital marketing firm, plus new digital warehouse shopping centre firms, as well as new logistical, marketing/deliveries health product firms. These in-house developments initiated: new software, new data usage, new logistical mapping, new digital wallet sales/security, new dashboard management, new workforce skilling, and new brand imaging. Other business including the XYZ Distillery, Triple Eight and BuildaDesk have executed similar changes due to COVID-19. The COVID-19 crisis has changed the Australian business landscape— creating new, more complex, pivot-capable, and more competitive business models.

This study concludes DUK’s 3Cs (competencies, capabilities and competitiveness) do offer an internal framework capable of advancing a firm towards retaining its business sustainability. It further concludes that the strategic change matrix sets the global framework to understand a firm. This strategic change matrix first aligns the firm’s existing competencies, capabilities and competitiveness components into a matrix-box. Second, it offers a comparison by establishing a second, strategically desirable, competitively expanded matrix-box (that now consumes the firm’s earlier matrix-box) with additional revised, strategically remapped pathways, and/or further business-enhancing components.

In DUK’s case, it combined its competencies, especially its digital assets, along with its agile capabilities. It add pivots to its firm competitiveness, and so expanded one dimension of its previous strategic change matrix. This created an additional set of new competitiveness dimensions to its business strategy. DUK’s increased business diversity also produced a sustainable business positioning that re-set its business direction into the immediate future. It now strategically assesses pivots when considering further strategic business changes.

Hence, the DUK 3Cs, Porter’s Five Forces, and DUK’s Pivot with Knowledge initiatives, coalesced into its strategic change matrix, has allowed DUK to: (1) map, and deliver, a defensive and supporting solutions-set for its existing marketing clients, and to also (2) map its own strategic change advancements into extending its market reach, growing/diversifying its market share, achieving a sustainable business presence, and growing its competitive advantage.

The DUK strategic change matrix-box solutions pathway is likely of particular relevance when a firm is confronted with a future economic or game-changing business crisis, or when a firm such as this study’s COVID-19 business cases of DUK, the XYZ Distillery, Triple Eight, and BuildaDesk, strategically chooses to pivot with knowledge, and to pursue an alternate business-enhancing pathway, or when a firm is investigating the future-proofing of its current business operations.

In times of crisis such as the economic decline created during the COVID-19 global pandemic, key futures-focused management consulting firms, like Gartner [

43], also suggest “expanded data collection”, “emergence of new top-tier employers” and “increases in firm business complexity” are three current firm deliverables areas that can add to future firm competitiveness solutions. These management consulting firm views align with DUK and its strategic change matrix approach.

This study concludes astute Australian firms are likely to be agile and flexible with in-depth internal and external analysis abilities. Across different industries, such firms likely understand their competencies and capabilities. It is also likely that they can evaluate their potential pivots and business modifications, and then target, enhancing their competitiveness.

This approach is particularly successful when such astute firms retain the strategic desire to research, formulate, innovate, implement, and make work, their chosen new firm approaches. Today, Australian firms seeking to improve their competitiveness can:

First, look externally, and pursue an in-depth understanding of their surrounding local and global competitive firm environment, their relevant industry, and their firm’s active competitors.

Second, look technically at virtual emergent technologies, thereby allowing a thorough understanding of potential emergent digital applications, and possible business shifts. These should then reframe their firm’s specific choices across its business-wide, smart connectivities workplace.

Third, look physically, and assess their internal deliverables as potential ‘fixes’ against the firm’s suites of operational capabilities fixes.

Fourth, brainstorm and investigate all conceived pivots, and also readdress the previous steps against each pivot.

Fifth, in conjunction with the above rapid-fire processes, each firm should strategically position their business within the above strategic change matrix shown in

Figure 3. They can then decision-target an optimal new future matrix-box position.

Sixth, to retain a strategic business sustainability position into the immediate future, each firm should consider reframing its 3Cs approach by refining their competencies and mixes of deliverables within the

Figure 3 strategic change matrix. Next, they use their refined 3Cs to remodel the firm with these component additions as deliverance pathways towards their targeted ‘optimal’ matrix-box solution for tomorrow.

These six steps likely have application whenever a firm is confronted with a future economic or game-changing business crisis, or when an astute firm strategically chooses to pivot with knowledge, and then chooses a new business-enhancing pathway. They also hold relevance when a firm just wants to map its business pathways into the future.

This study’s new 3D strategic change matrix approach helps to visually map the components of a firm’s competitiveness. Although developed by DUK, and its academic researcher, it can be utilised by most substantive firms—particularly when mapping a strategic business expansion, business consolidation, business retraction, or business pivoting change.

The theoretical contribution to this study lies in the build of the 3Cs framework (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Embedded across this framework are DUK’s component constructs and their specific measurement indicators (which remain its confidential property). Another contribution is the dynamic nature of the strategic change matrix. DUK added a ‘pivot’ component to the firm’s competitiveness axis of

Figure 3. This important

Figure 3 addition can now be considered by a firm —particularly in times of crisis such as when it may need to deliver an agile shift that incorporates a new or enhanced competitive business direction. Further, into the future, new knowledge such as that embedded in Microsoft’s developing of its ‘Democratising AI’ components can likely add to the competencies and capabilities axes. Again, the dynamic nature of the strategic change matrix and its application is exemplified.

Hence, the strategic change matrix in

Figure 3 is dynamic in nature, and expandable in terms of components coverage. It is likely of real use to real firms when strategically assessing what makes their firm competitive. It is also useful when finding a future change matrix-box position or when assessing a competitor’s matrix-box for differences, or even when assessing a competitive market. Thus, the strategic change matrix is likely to have wide firm and business applications.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study captures the business crisis in Australia during the COVID-19 global pandemic time period. It adapts DUK’s ongoing strategic marketing approaches. The study explains how during COVID-19, the digital marketing firm DUK, used its own strategic change matrix, designed for its clients, and deployed it as a means to reposition itself for the immediate future into a new sustainable competitive business position.

This mixed methods approach cannot release the actual quantitative constructs and measures due to DUK’s IP and confidentiality restrictions. Nevertheless, it does give the block levels, shown in

Figure 2, from which researchers can investigate their own construct measures, and then test them over time against the strategic change matrix.

The study shows that pivoting is a useful business strategic inclusion that should be considered when a firm faces a strategic change of position decision. Although the strategic positioning matrix likely has applications across many agile and digital business environments, and across different industries, it likely of most use when applied to firms of a substantive size.

The strategic positioning matrix is a dynamic, expandable structure. New inventions and components that can contribute to a firm’s sustainability, can be logically position-added into the strategic positioning matrix. Thus, researchers are encouraged to extend a firm’s competences and capabilities, and competitiveness (3Cs) by further developing its internal components into additional measurable constructs with measurement indicators.

This area of business research is ongoing, and digitally, it is moving in line with Microsoft’s Democratising of AI inclusions, where technologies and intelligences help fuse humans and machines together - delivering smarter accessible knowledge to all. This digital driving force is a necessary area for firms seeking to remain competitive, and to advance their strategic change matrix- box position. This extends to the need to incorporate stakeholders’ requirements, and to help support the firm’s business sustainability. Into the future, this logically extends to changing how lives are influenced, how digital apps can further extend the delivery of cognitive capabilities, and how cloud supercomputing competencies and capabilities can integrate as enhancing components into each firm’s strategic change matrix business solutions.

In addition, emerging management, marketing, psychological, digital, industry, and firm discoveries (or applications) can be assessed for positional inclusion into a strategic change matrix approach. Researchers can also initiate further new business 3Cs and/or ongoing sustainability studies. Such component findings can also be strategically considered, mapped and possibly dynamically included as improvements towards extending this study’s strategic change matrix.