Abstract

Background: Lactoferrin (Lf ) has been shown to have antiviral action against a variety of animal and human viruses, particularly deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses. This review aims to summarize the pharmacological activities that lead to the influential role of Lf against SARS-CoV-2.

Methods: An all-inclusive search of published articles was carried out to focus on publications related to Lf and its biological/pharmacological activities using various literature databases, including the scientific databases Science Direct, Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Google Scholar, Google, EMBASE, and Scientific Information (SID).

Results: By acting on cell targets, Lf prevents viral attachment, surface accumulation on the host cell, and virus penetration. Lf has shown high antiviral effectiveness across a broad spectrum of viruses, suggesting that it might be used to cure and prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Lf can also attach to viral particles directly, such as hepatitis C virus (HCV), and steer them away from certain sites. LF has a powerful attraction for iron, with a constant of approximately 1020. Lf capacity to link iron relies on the existence of (minute amounts of ) bicarbonate. The bacteriostatic effect of Lf is due to its capability to come together with free iron, which is one of the ingredients necessary for bacterial development. Lf located in neutrophil secondary granules is essential for host defense.

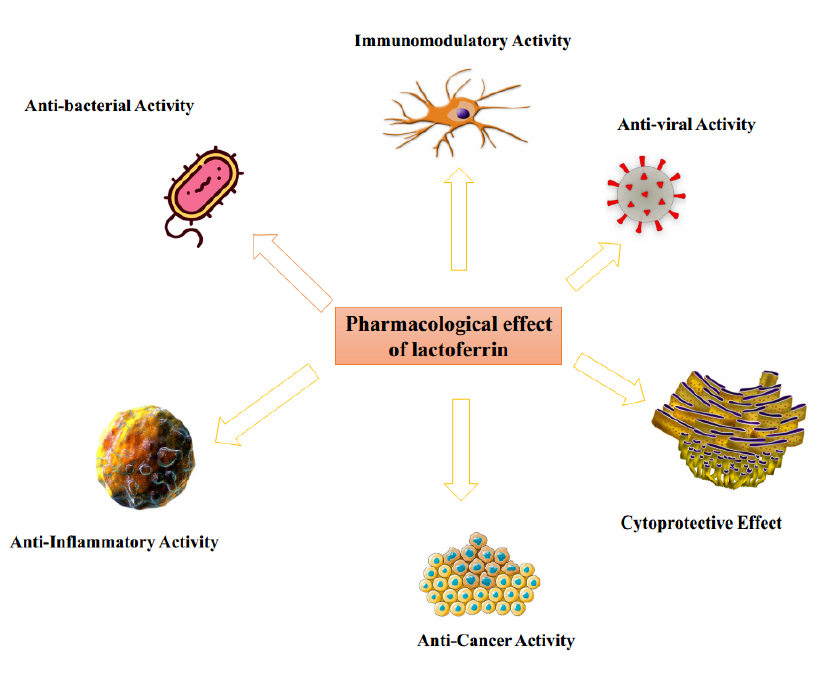

Conclusion: Researchers confirmed that Lf activates natural killer (NK) cells in a study. Lf has been shown in certain studies to prevent patronization in pseudovirus severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) cases that leads to attenuation of SARS-CoV-2. Lf may decrease inflammation induced by microbial exposure and directly reduce bacterial growth. It is concluded that Lf possesses antibacterial, immunomodulatory, anticancer, antiviral, cytoprotective, and anti-inflammatory activities, which ultimately act as an antiviral against SARS-CoV-2 via various mechanisms.

Introduction

Lactoferrin (Lf) is a 14-glycan single-chain polypeptide with a molecular weight of 80,000 Da, depending on the origin of the species. Human Lf (hLf) is made out of 691 amino acids, and bovine Lf (bLf) is made out of 689 amino acids, with a sequence similarity of 69%1. Each Lf molecule includes two parallel lobes, referred to as the C- and N-lobes, respectively, according to the C-terminal and N-terminal parts of the molecule. These domains are designated N1, N2, C1, and C2, respectively. bLf and hLf have comparable three-dimensional structures, but they are not identical. The second configuration is aided by disulfide bonds in cysteine residues. bLf is only partly iron-saturated (15 — 20%) in its natural state, giving it a brilliant pink hue with varying sharpness depending on the extent of iron saturation. Apo-Lf is iron-exhausted Lf with less than 5% iron saturation, whereas holo-Lf is iron-saturated Lf2. Apo-Lf is the most common Lf found in breast milk. Lf has a very strong affinity for iron, with a constant of approximately 1020. The capacity of Lf to bind iron relies on the occurrence of (little quantity of) bicarbonate3. The capacity of Lf to bind iron depends on bicarbonate levels, which are negatively impacted by elevated amounts of citrate. On the other hand, citrate can separate from bLf, which is comparable to the in vivo situation in milk. The N-terminus of both hLf and bLf are substantial cationic peptide sequences that contribute to many essential interaction characteristics4. A loop in the N1 region with a high affection binding area mediates bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding with human and bLf; the C-lobe seems to have poor affection binding regions. The human loop is 28-34 amino acids long, whereas the bovine loop is 17 – 41 amino acids long5. Due to biological activities, Lf has evolved in various species, including humans. It has been evaluated for a long time. Lf correlates with an iron deficiency linked to bacteria directly, which can impact viruses and parasites. In addition to its protective properties against bacteria, Lf also has immunomodulatory effects on immature immune systems. Peptides derived from limited Lf proteolysis, which may occur when Lf is consumed, have been found to retain the majority of the Lf protective qualities, sometimes to a greater extent6.

The bacteriostatic effect of Lf combines with that of free iron, which is one of the components needed for bacterial development7. Escherichia coli (E. coli) and other iron-dependent bacteria cannot thrive if they do not have enough iron8. On the other hand, Lf may serve as an iron supply, encouraging the growth of bacteria that need less iron, such as Lactobacillus sp. or Bifidobacterium sp., which are normally regarded as beneficial bacteria9. The bactericidal properties of Lf have also been discovered. The effects of bLf and hLf on the immune system have been studied in a variety of ways. Despite conflicting evidence, Lf seems to have both immunomodulatory and immunostimulatory characteristics10. The ability of Lf to bind endotoxin is believed to be important in immunomodulation. The quantity of immune system activation is decreased by binding bacterially generated endotoxin to Lf. This mechanism may avoid overstimulation, which may occur during a condition such as sepsis11.

Several antibacterial, antimicrobial, and immunomodulatory characteristics have been ascribed to Lf throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Nevertheless, it was not until 1994 that Bezault et al.12 presented convincing evidence of hLf anticancer action in mouse models of fibrosarcoma and melanoma. Injections of hLf into the peritoneal cavity, in particular, have been demonstrated to prevent solid tumor development and lung metastasis, independent of how quickly the protein absorbs iron. Several studies have shown that Lf can combat cancer by activating natural killer (NK) cells. Zang et al.13 found that employing a methyltransferase blocker to restore hLf gene transcription reduced cancer cell growth and metastasis in an oral squamous cell carcinoma system. Due to their great selectivity for cancer cells and minimal toxicity for normal cells, antimicrobial peptides are also being used in several novel cancer therapies. hLf, bLf, and their related peptides have been investigated and confirmed to play an important role in cancer prevention and therapy due to their comparable cell selectivity11.

The antiviral activity of Lf was found much later, although much data have been collected since then, as shown by the significant investigations of Van der Strate et al.14. Lf has only been proven to be crucial in avoiding viral infection in a few cases. On the other hand, Lf has an inhibitory impact on a wide variety of viruses15. This group includes a variety of enveloped viruses, such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1 and 2, human cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), hantavirus, and four naked viruses, rotavirus, poliovirus, adenovirus, and enterovirus 7116. Both hLf and bLf have inhibitory effects, which are mediated not only by adhering Lf but also, in certain cases, by enzymatic fragments of the molecule, as observed in HSV, cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, and rotavirus17. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress inhibition is related to the cytoprotective effect of Lf. Hepatic phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (p-eIF2) and phosphorylation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (p-NF-κB) were significantly higher in ob/ob mice than in Lf-treated ob/ob mice. This implies that Lf therapy may reduce ER stress caused by hepatosteatosis18. Due to its cytoprotective properties, Lf has been found to minimize ER stress and autophagy formation in injured hepatocytes. It stimulates the upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha/vascular endothelial growth factor (HIF-lα/VEGF) to aid in hepatic activity recovery19. Recent research revealed that Lf has a cytoprotective impact on the survival of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) that had been subjected to H2O2-induced oxidative damage using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) test20.

According to the study, Lf may decrease inflammation induced by microbial exposure and directly reduce bacterial growth. Lf therapy inhibits Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis, LPS-induced gut mucosal viability, endotoxemia, and mortality caused by systemic E. coli or LPS exposure, according to animal research21. Lf may decrease inflammation by reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin -1β (IL-1β), and IL-6, according to in vitro and in vivo investigations in mononuclear cells and mice22. The capability of Lf to attach molecules that connect to the Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway, which is essential for the subsequent host inflammatory response to microbial invasion, may be the primary mechanism behind this impact23.

The ability of Lf to suppress pseudotyped severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) with an IC50 of 0.7 M is very relevant to the current research. Human coronavirus is most often linked with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)24. The capability of Lf to bind to cell membrane receptors, viral particles, or both may contribute to its capacity to hinder viral entry. According to recent research, viral entry is a difficult process involving cell surface components, virus attachment, and adhesion to a more significant attractive cellular receptor to begin cell penetration. Lf limits viral entrance and suppresses virus growth after it reaches the cell in the case of HIV. Lf may thus have an indirect antiviral impact on immunological cells, which are essential during the initial phases of viral infection25. Lf and ovotransferrin act directly against viruses and bacteria that may cause secondary infections in COVID-19 patients, thus protecting them against infections that might occur. These antimicrobials early on, when noncritical conditions appear, can help prevent them from becoming complicated26. They can also be used as a preventive for those who are more susceptible to infection, with smaller doses being given, reducing the chance of infection. Oral consumption of Lf is the most effective method since the number of SARS-CoV-2 conditions is increasing27. Lf and ovotransferrin, in particular, exhibit systemic effects after ingestion. Lf-containing milk or Lf-supplemented yogurt helps treat viral infections in studies28. The main objective of the present review is to summarize the pharmacological activities and protective role of Lf against SARS-CoV-2 infection with possible molecular mechanisms.

BIOCHEMISTRY OF LACTOFERRIN

Lf are single-chain polypeptides that include 1-4 glycans and have an average molecular weight of approximately 80,000 Da, based on species1. Because of Baker and colleagues' groundbreaking research, the 3-D conformations of bLf and hLf have become understood in precise detail29, 30. A thorough investigation by Montreuil, Spik, and colleagues clarified the architecture of glycans related to Lf in various species31, 32. Although the three-dimensional structures of bLf and hLf are similar, they are not identical. According to the C-terminal and N-terminal portions of the molecule, every Lf molecule contains two parallel lobes, the C- and N-lobes, respectively. N1, N2, C1, and C2 are the designations of all these domains, correspondingly33. In bLf, N1 represents the sequences 1-90 and 251-233, N2 represents 91-250, C1 represents 345-431 and 593-676, and C2 represents 432-592; the sequence 334-344 represents the so-called hinge, which is a three-turn helix structure that plays a key role in domain opening and closing34. The existence of disulfide bonds within cysteine residues contributes to the second configuration. When the amino acids Asp60, Tyr92, Tyr192, and His253 cleave from the protein, they lead to ferric ion binding; in both lobes, (bi)carbonate competes with iron for binding1. The Asn residues at locations 233, 281, 368, 476, and 545 in bLf are five possible locations for N-glycan confirmation. Nevertheless, scientific research demonstrates that only four N-linked glycans, Asn281, seem to be omitted33. The amino acid Asn476 appears to be conserved throughout animals. Spik et al.32 provided an excellent review of the glycans linked to Lf from several species, demonstrating the diversity of these structures35.

Iron binding

Lf present in breast milk is mostly apo-Lf. Lf has an extremely high affinity for iron and an attraction constant of approximately 102036. The ability of Lf to bind iron is based on bicarbonate availability (minute quantities). The interaction site appears to be optimized for binding ferric iron and bicarbonated area, charge, and stereochemistry. It is evident from many conformational studies that using different anions and cations or utilizing genetically changed genes Lfs37. In terms of iron binding, oxalates may substitute for bicarbonates but not citrate. On the other hand, citrate can attach to bLf in separation, which is consistent with the in vivo scenario in milk. High amounts of citrate may reduce Lf’s ability to bind iron, relying on bicarbonate levels38. Other cations, such as copper, could be bonded in the aperture and alter the intake of the optimum wavelength. For example, ferric iron-saturated Lf absorbs best at 466 nm, while copper (Cu2+)-saturated Lf absorbs best at 434 nm. Mn3+, Co3+, and Zn2+, in addition to Cu2+, might be connected39.

Ward et al.40 recovered C- and N-lobe hLfs from Aspergillus awamori. It had been changed for alanine, whether in the C-lobe or the N-lobe, and two tyrosine residues important in iron-binding, using site-driven mutagenesis. According to their results, the C-lobe has a more prominent role in iron stability than the N-lobe. The iron-binding domains of both Lfs' N-lobes were examined41, 42. Using pH-induced iron discharge studies, they discovered that the absence of the Asp60 residue in domain N2 did not affect iron retention. They also found evidence of iron stabilizing connections between the N-lobe (30 kDa tryptic fragment) and the C-lobe (a 50 kDa tryptic fragment)43. When the pH fell under 4, bLf began to discharge iron, while hLf was more resilient to discharge when the pH fell under 344. Furthermore, they demonstrated that complete deglycosylation of both tryptic N-lobe segments resulted in a 50 — 100% decrease in iron-binding ability. Nevertheless, no reduction in iron-binding was observed in experiments using adherent deglycosylated recombinant hLf35.

Strong cationic N-terminus

Both hLf and bLf include significant cationic peptide sequences at the N-terminus, contributing to various essential interacting properties. The interaction of bacterial LPS with human and bLf is mediated by a loop in the N1 region with a high attraction binding area; the C-lobe appears to have weak attraction binding regions (100 – 130 times lower affinity)4. The human loop is composed of 28-34 amino acids, whereas the bovine loop consists of 17-41 amino acids. Preeti et al.,45 and Van Berkel et al.,46 investigated the interaction of hLf with heparin, lysozyme, LPS, and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) using intact and N-terminally removed Lf. They showed that iron saturation did not affect the four-compound interaction. The removal of one or more arginine residues (Arg2, Arg3, Arg4, and Arg5) reduced Lf interaction to various degrees, with the deletion of more arginine residues having the most significant impact. Having recombinant Lf lacking the first five amino acid residues (Gly1-Arg2-Arg3-Arg4-Arg5), there was no interaction45. This shows how vital this length of four arginine residues in biomolecule association is for host defense.

According to Legrand et al.41, the number of binding domains of hLf for human lymphoblast T cells was most remarkable for the whole molecule. Nevertheless, it gradually decreased from approximately 100 000 per cell to 17 000 per cell when Arg2, Arg3, and Arg4 were removed47. The binding characteristics of intact hLf and bLf were quite similar. According to scientists, the interaction takes place on the cell's sulfated molecules, and the Arg5 residue has no function. Due to its known antibacterial action, the cationic N-terminus of bLf is of particular interest35.

THE PHARMACOLOGICAL EFFECT OF LACTOFERRIN

It has antimicrobial, antiviral, and immunomodulatory properties, which affect both the developing and immature immune systems. Lf is orally injected and has previously been associated with iron deficiency but is now related to direct association with bacterial cell walls48. It is important to mention that peptides produced from minimal Lf proteolysis that may be produced upon Lf intake have been shown to contain most of the Lf protective properties, occasionally to a higher degree49.

Antibacterial Activity

Lf bacteriostatic action is due to its ability to attach free iron, one of the components required for bacterial development36. Iron-dependent bacteria such as E. coli cannot grow if they do not have enough iron50. On the other hand, Lf may act as an iron supplier, boosting the growth of bacteria with fewer iron needs, such as Lactobacillus sp. or Bifidobacterium sp., which are generally regarded as beneficial bacteria51. However, certain bacteria can adjust to the changing circumstances and produce siderophores (bacterial-derived iron-chelating chemicals) that strive with Lf for Fe3+ ions52. Several bacteria, such as those in the Neisseriaceae family, are adaptive to changing circumstances by producing particular receptors that attach Lf and induce variations in the Lf molecule tertiary shape, resulting in iron dispersion53.

Lf has also been shown to have bactericidal action (Figure 1). This bactericidal action is not iron dependent, and many mechanisms could induce it. On the membrane of certain bacteria, receptors for the Lf N-domain have been identified. Lf interacting with these receptors causes Gram-negative bacteria to die by disrupting their cell walls, resulting in cell death54. The subsequent removal of LPS reduces permeability and increases susceptibility to lysozyme and various antimicrobials. Even if Lf does not contact the cell surface, LPS may eliminate it. Electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged lipid layer and the positively charged Lf layer produce bactericidal activity against gram-positive bacteria55. These interactions make a substantial difference in membrane permeability. Lactoferricin, a cationic peptide formed when Lf is digested by pepsin, shows bactericidal activity.

Due to the merging of secondary granules and phagosomes, Lf acts as a source of iron for the catalysis of available radical generation. It increases neutrophil intracellular bactericidal action. Lf inhibits the development of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in vitro56. Bacteria are forced to migrate due to a shortage of iron in their surroundings. As a result, they are unable to attach to surfaces. Lf may play a role in preventing pathogen adherence to recipient cells by adhering to both target cell surface glycosaminoglycan and bacterial invasions57. This capacity was initially documented against enteroinvasive E. coli HB 101 and then against Yersinia enterocolica, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, Listeria monocytogenes, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus58. Lf proteolytic action is thought to limit the development of certain bacteria, including Shigella flexneri and enteropathogenic E. coli, by destroying proteins required for colonization. Serine protease inhibitors, on the other hand, may prevent this59.

Immunomodulatory Activity

The usage of bLf and hLf in the immune system has been investigated in several types of research. Despite contradictory findings, Lf appears to have dual immunomodulatory and immunostimulatory properties (Figure 1). The capacity of Lf to attach endotoxin is thought to play a significant role in immunomodulation53. Gram-negative bacteria are subjected to different innate immune system proteins when they infect a human host. TLR-4 recognizes this "pathogen-associated molecular pattern". It triggers a range of immunological reactions in different leukocytes and platelets11. Immune system activation is decreased by attaching bacterially produced endotoxin to Lf. This mechanism may avoid overstimulation, which can occur during a condition such as sepsis. According to current research, the hLf 1-11 peptide produced from human lactoferricin may block myeloperoxidase. It is a key host-defense enzyme present in different leukocytes, potentially lowering innate immune activity60. In contrast, hLf has been demonstrated to promote the differentiation of dendritic cells and the recruitment of different leukocytes. As a result, the protein acts as an innate and adaptive immune system activator61.

Lf, which is found in neutrophil secondary granules, is crucial for host protection. Neutrophils may react to harmful bacteria in many formats. Neutrophils may degranulate at the infected area, releasing the host defense protein mixture in secondary and various secretory granules. These factors may combine to produce a significant localized reaction to bacterial attack61. Neutrophils swallow invading microorganisms during the phagocytosis phase once a microbe is caught within the neutrophil. The phagocytic vacuole merges with the granules, and the bacteria are natively destroyed. The formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which are used in the third stage, is caused by DNA escaping from neutrophil nuclei24. In a "kamikaze-like" process, intracellular granules mix with the nucleus, while host defense proteins, such as DNA and nuclear proteins, are all released into the extracellular space62. Bacteria are subsequently captured in NETs, where host defense proteins may attack them. Lf may attach to DNA, and because of its strongly positively charged N-domain, it will stay linked with ejected DNA in the NETs, in which it can continue to aid in bacterial death. Because several proteolytic enzymes are expelled from the granules, lactoferricin or specific peptides may also be excreted locally from the adhering Lf protein. However, this possibility has not yet been explored63.

Anticancer Activity

The anticancer potential of Lf has been linked to the stimulation of NK cells in a similar study. However, there is a negative correlation between endogenous hLf production and the prevalence of cancer in some cancer cell lines, which is associated with a substantial reduction in hLf messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA). Lf gene silencing has been related to some molecular events in cancer cells, including regulator and gene hypermethylation, along with actual gene sequence alterations. Zhang et al.13 showed that restoring hLf gene transcription with a methyltransferase blocker reduced cancer cell growth and metastasis in an oral squamous cell carcinoma system. Both hLf and bLf were proven to have anticancer action in protecting and treating tumors. Lf therapy was shown to be effective in suppressing development, metastasis, and tumor-related angiogenesis and in enhancing chemotherapy in many experimental animals harboring various kinds of cancers, notably lung, tongue, esophageal, liver, and colorectal cancer.

Although Lf use in clinical studies for tumor protection in humans is nearly impossible for most cancers, studies on its possible usages during the cure of certain precancerous lesions to avoid their transition into potentially tumorigenic cells have been conducted. The Tsuda research team investigated the inhibitory action of orally administered bLf on the formation of precancerous adenomatous colorectal polyps in a clinical trial performed at the National Cancer Center Hospital in Tokyo, Japan, between 2002 and 2006. Individuals were randomly allocated to receive 0 (placebo), 1.5, or 3 g of bLf each day for a year64. The findings revealed that the smaller dosage had no impact. The more potent dose was effective in slowing the development of colorectal polyps in individuals aged 63 or younger relative to the placebo group. Surprisingly, serum hLf concentrations in patients receiving 3 g of bLf were found to be significantly higher after 3 months of therapy, indicating an increase in neutrophil activity64 . The research was enhanced in 2014 when a similar group presented data on the relationship between immunological characteristics and polyp size65. Enhanced NK-cell action and greater concentrations of the cluster of differentiation 4+ (CD4+) cells in the growth were sustained with adaptive immunity stimulation. It also reduced the concentrations of polymorphonuclear neutrophils, and growing levels of S100A8+ cells in the polyps, sustained with downregulation of inflammatory stimuli, were seen in study subjects with regressing cysts. Consequently, even though the molecular processes are still unknown, the Tokyo clinical study is a significant step forward in demonstrating the efficacy of oral bLf treatment in preventing cancer in people66.

Aside from broad clinical implications, many molecular pathways underpinning Lf anticancer activity have been discovered, such as cell cycle regulation, apoptosis promotion, migration and invasiveness inhibition, and immunomodulation67. Except for the indirect immunomodulatory mechanism, the other processes necessitate Lf's direct identification and choice of tumorous and normal cells, involving a central association with unique tumor cell surface receptors or a secondary interaction through differential intracellular network regulation68. Few examples of initial identification between Lf and tumor cell surface receptors have been documented thus far. In this regard, tumor cells usually have significant levels of proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and sialic acids, all of which are recognized Lfs interactors69. Lf anticancer specificity and sensitivity may be based on this poor detection. The N-terminal region of hLf, which includes a unique sequence of four consecutive arginine residues (G1RRRR5), was required for hLf interaction with GAGs on the human colon carcinoma cell line HT29-18-C1 as well as Jurkat human lymphoblastic T cells70. Surprisingly, the N-terminal portion of bLf, which has a unique consensus sequence (A1PRKN5) compared to hLf, may bind with cell membrane-linked GAGs.

Furthermore, Riedl et al.71 discovered that phosphatidylserine, a cytoplasmic-membrane constituent abundant in tumor cells, is a critical focus for the unique anticancer action of human lactoferricin derivatives. This main selective association through cell surface receptors may explain the most ancient role attributed to Lf, namely, its lethal effect. Similarly, large dosages of both hLf and bLf, as well as their generated peptides, have been demonstrated to cause cytotoxicity and cell death in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathogens, as well as tumor cells. Lf cationic charge, which may enhance electrostatic associations with negatively charged cell surface receptors, has been linked to this function72. The reduced particular mass weight of Lf-generated cationic peptides may readily penetrate and disrupt cell membranes, causing lysis73. In addition, antimicrobial peptides are used in several recent cancer therapies because they have excellent selectivity for cancer cells and minimal toxicity for normal cells. Because of their similar cell selectivity, hLf, bLf, and their associated peptides have been studied and proven to play an essential role in cancer prevention and therapy66, as shown in Figure 1.

Antiviral Activity

Lf was only shown to effectively prevent viral infection in several instances (Table 1). In contrast, many viruses are susceptible to Lf inhibitory effects. This group includes various enveloped viruses, such as HSV 1 and 2, human cytomegalovirus, HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, RSV, hantavirus, and four naked viruses (rotavirus, poliovirus, adenovirus, and enterovirus 71)74 that Lf has been shown to diminish suppress (Table 1). This inhibitory action is shown in both hLf and bLf. This is mediated not only by adherent Lf but also by enzymatic fragments of the molecule, as seen in HSV, cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, and rotavirus75. The impact on viral illness does not seem to be linked to removing iron from the surroundings. It has been seen in various instances, often with metal-saturated Lf isoforms. However, the explanation for this is unclear. Regarding the mode of action of Lf on viruses, it is widely recognized that the inhibitory effect occurs during the initial stages of viral penetration instead of blocking virus multiplication after infection of the host cell60, as shown in Figure 2. Lf binds directly to several sensitive viruses. Antiviral activity can also be achieved by linking to target cell molecules, which the virus uses as a receptor or coreceptor76.

Lf antiviral action has also been shown in a limited in vivo study. Lu et al.77 reported the initial discovery, observing that Lf increased survival chances in mice treated with the Friend virus complex. Before viral introduction, Fujihara and Hayashi78 found that superficially applied bLf inhibited HSV-1 development in the murine cornea. Shimizu et al.79 discovered that iron-saturated bLf protects mice from cytomegalovirus infection. Ultimately, Tanaka et al.80 showed that bLf reduces HCV viremia in chronic hepatitis C patients. A finding was later confirmed by Iwasa et al.81 in patients with high viral loads and HCV genotype 1b. Apart from its direct impact on viral components or host cells, Lf has been shown in vivo to have an indirect impact via its effect on immune cells, as shown in vivo toward the Friend virus complex and murine cytomegalovirus. The ability of Lf to attach precisely to many virus particles or viral receptors has indicated that this protein might be used to selectively distribute antiviral medicines82, as shown in Figure 2.

Moreover, due to its reported impact on SARS-CoV internalization and its capacity to reduce the inflammatory reaction, Lf may have a preventative role in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lf has been shown in certain trials to prevent pathogenesis by the pseudovirus SARS83. In this regard, it is thought that breast milk, which consists of a substantial portion of Lf, can provide considerable prevention to newborns toward the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. On the other hand, additional research is needed to understand the novel coronavirus behavior and treatments. However, Lf appears to be an up-and-coming preventive option15. Its antiviral effects are derived from blocking receptors such as heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan cell receptors. Its interaction with viral hemagglutinin (HA) allows Lf to penetrate the viral coating. The glycosylation characteristic of the molecule may provide an important understanding of these interactions. Certain studies have shown that changing the glycosylation of the molecule can change the signaling strength of different TLRs participating in viral particle identification, such as TLR-3 and TLR-824. Despite its great tolerability, the results of LF as an oral supplement remain irregular, both in terms of prevention and treatment of viral infections. Oral supplementation with LF is well tolerated. However, the results of viral infection prevention and treatment remain mixed. Because of the wide range of recruiting and treatment methods used, as well as the poor research quality, the results are likely to be heterogeneous. SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses will need to be studied in more detail in studies with better designs84.

| Type of virus | Enveloped/naked | DNA/RNA | Sources of LF | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A | Enveloped | RNA | Bovine | Interfering with viral hemagglutinin fusogenic activity | 85 |

| RSV | Enveloped | RNA | Human | Modulating RSV-induced IL8 expression and RSV F protein attachment | 86 |

| adenovirus | Naked | DNA | Bovine | Competing with viral particles for cell membrane HS incorporated in target cell membranes by binding to the adenovirus penton base. | 87 |

| SARS‑CoV | Enveloped | RNA | Human | Promoting natural killer cell activity and neutrophil aggregation and adhesion by attaching to heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan (HSPG) and inhibiting the initial interaction between SARS-CoV and host cells | 88 |

| Enterovirus 71 | Naked | RNA | Bovine | Binding to viral protein 1 protein and host cells | 89 |

| Cytomegalovirus | Enveloped | DNA | Human | Lf prevents CMV cell invasion and has indirect antiviral effects on CMV infections by stimulating the immune system | 90 |

| HSV‑1 | Enveloped | DNA | Bovine | By competing with HSV 1 for the heparan sulfate receptor on the cell surface and inhibiting VP 16 from being translocated to the nucleus, it affects a postentry step of viral infection | 91 |

Cytoprotective Effect

Protein chaperones are made from the ER, which is a protein-folding machinery. The ER is responsible for protein folding and detects misfolded or unwrapped proteins. Pathological analyses suggest that ER stress is a frequent source of a variety of illnesses, particularly when the stress is solid or persistent enough to induce cell death or damage. Whenever ER stress is constant and the ER folding limit is exceeded, cellular malfunction and cell mortality are common outcomes92. Disruption of typical ER activities triggers an evolutionarily conserved cell stress reaction called the unfolded protein reaction. It is designed to accommodate damage but may eventually induce cell mortality if the ER is severely or chronically dysfunctional93.

In that study, leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mice were used as animal models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Lf protects Ob/ob mouse liver tissues from oxidative and ER stress. Due to the involvement of hepcidin-induced obesity and hepatic lipid deposition, ER stress has recently been recognized as a cause of iron homeostasis control94. Recombinant hLf is given intraperitoneally to relieve or postpone the pathological development of NAFLD to assess Lf hepatoprotective properties18. The activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2 and eIF2), as well as NF-κB stimulation and oxidative stress, was shown to be reduced in the liver tissues of LF-treated ob/ob mice compared to vehicle-treated ob/ob mice95. Consequently, it is suggested that the cytoprotective function of Lf is linked to the inhibition of ER stress. The hepatic p-eIF2 and p-NF-κB expression rates were significantly greater in ob/ob animals than in Lf-treated ob/ob mice. This suggests that Lf treatment may reduce ER stress induced by hepatosteatosis96. It has been demonstrated that Lf prevents ER stress and the development of autophagy in injured hepatocytes due to its cytoprotective effect. It also induces upregulation of HIF-lα/VEGF to aid hepatic activity retrieval97.

A recent study showed that Lf had a cytoprotective impact on the survival of HUVECs that had been subjected to H2O2-induced oxidative damage using the MTT assay98. HUVECs were pretreated with Lf at 25–100 µg/ml doses, which decreased cell mortality caused by H2O2 in a concentration-dependent manner. The survival of HUVECs (P < 0.001) was significantly reduced after 2 hours of treatment with 0.5 mM H2O2. No cytoprotective activity was detected at 6.25 and 12.5 µg/ml Lf98.

Anti-Inflammatory Effect

Along with directly inhibiting bacterial growth, research indicates that Lf may reduce the inflammation caused by microbial exposure. Animal studies have shown that Lf therapy protects against Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis, LPS-induced gut mucosal viability, endotoxemia, and mortality caused by systemic E. coli or LPS exposure23. In vitro and in vivo studies in mononuclear cells and mice show that Lf can reduce inflammation by decreasing the production of a variety of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-699. This effect could be accomplished primarily by the capacity of Lf to bind molecules that link with the TLR signaling pathway, which is critical for the subsequent host inflammatory process to microbial invasion. Lf has demonstrated that LPS, soluble CD14, and unmethylated cytosines followed by guanine residues (CpG) bacterial DNA are binding and attenuating directly via an immune-stimulating reaction43. Finally, in vitro studies in monocytic cells suggest that the anti-inflammatory effect of Lf in response to LPS exposure may be related to reduced proinflammatory cytokine synthesis. It follows Lf translocation to the nucleus, which suppresses NF-κB activation100.

The opposing-inflammatory impact of Lf is rapidly being recognized as extending beyond reducing microbial-induced inflammation101. Inflammatory diseases such as neurodegenerative illness, inflammatory bowel disorder, dermatitis, pulmonary diseases, and arthritis have been shown to stimulate Lf. Furthermore, Lf treatment has been demonstrated in most animal experiments to reduce experimental inflammation in such organs102. For instance, Lf prevents chemical and IL-1β -driven cutaneous inflammation in humans and animals, chemically induced inflammatory bowel disease in rats and mice, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)-induced colon damage in rodents, and inflammation in a rat model of rheumatoid arthritis103. This resistance was linked to a reduction in proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, and/or an enhancement in anti-inflammatory cytokines, like IL-10, in several instances104. The potential of Lf to engage with particular receptors on a wide range of immune cells, such as neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes, as well as epithelial cells. It indicates that Lf anti-inflammatory action could be responsible for the observed influence on modifying cytokine secretion by these cells primarily through receptor-mediated signaling mechanisms105. In a sheep model of allergic asthma caused by tryptase imbalances, several additional mechanisms by which Lf may inhibit the inflammatory reaction have been proposed, including the prevention of iron-catalyzed complimentary radical deterioration at areas of inflammation and the elimination of later stages airway blockage and hyperresponsiveness60. Campione, E., et al.6 revealed that Lf as a protective natural barrier of respiratory and intestinal mucosa against coronavirus infection and inflammation.

ANTIVIRAL ACTIVITY OF LACTOFERRIN AGAINST SARS-COV-2

Lf has been shown to have extensive antiviral action against a variety of human and animal viruses, including DNA and RNA viruses25, 106. In the 1980s, mice inoculated with the friend virus complex polycythemia-inducing form were shown to have antiviral activity77. Lf is particularly relevant to the present study to eliminate pseudotyped SARS-CoV at a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC 50) of 0.7 M (Lang et al., 2011). The most common reason for developing COVID-19, in this case, is SARS-CoV-224.

The capability of Lf to prevent viral entrance might be due to its capacity to attach to cell membrane receptors, viral particles, or both. According to new findings, viral entrance is a complicated procedure requiring cell surface molecules107. To initiate cell penetration, these chemicals are first attached to the virus and then to a greater affinity for cellular receptors108. Lf can also attach straight viral particles, such as HCV, to redirect them away from specific sites109. In HIV, Lf inhibits virus proliferation once it reaches the cell, in addition to limiting viral entrance110. Subsequently, Lf can have an indirect antiviral impact on immunological cells, which are important in the initial phases of viral infection.

Two-stage correlation with host cell receptors

The virus must first adhere to it and later perforate the cellular membrane to enter the host cell. Near the N-terminus of Lf, a strongly alkaline area may be coupled with several negatively charged macromolecules25. This is a key component of Lf antiviral action since many macromolecules, such as GAGs, often serve as receptors on host membranes, which enable viruses to interact with them111, 112. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) have been shown to suppress viruses such as human RSV, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus113, Echovirus114, HSV, dengue111, and others115.

COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV-2 is similar to SARS, as it is a positive-strand RNA virus with spikes, envelopes, membranes, and nucleocapsid proteins. It is dangerous to public health because of its high infectivity, death rates, and low recovery percentages116. SARS-CoV binds to host cells via HSPGs117, which Lf also uses to adhere to target tissues118. Lf has been demonstrated to protect the host against various viral infections by preventing viruses such as HSV from internalizing and filling their attachment sites119. The consequences of Lf on 293E/angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)-Myc cells infected with SARS-CoV pseudovirus have been studied88. HSPGs (attachment points that allow SARS-CoV to enter the cell) are scattered across the target cell membrane. Lf binds to such attachment sites to inhibit SARS-CoV internalization and disease in infected cells during the initial phase. As a result, Lf may be a promising therapeutic approach for shielding target cells against SARS-CoV pathogeneses.

SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 share 80% of their genomes and have comparable receptor-binding domain (RBD) configurations, and ACE2 and the RBD 1 helix form a polar bond with the ACE2 peptidase domain (PD)120. The main receptor of SARS-CoV-2 has been identified as ACE2, but another disputed independent receptor of SARS-CoV-2 is dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN)121. DC-SIGN might play a role in ACE2-mediated illness122. However, no research has shown that Lf can protect host cells via its association with ACE2. By attaching to cell membrane sites such as DC-SIGN, heparan sulfate, and low-density lipoprotein receptors, Lf has been shown to defend host cells from dengue virus invasion123. As a result, Lf may block ACE2-mediated illness by interacting with DC-SIGN.

Furthermore, ACE2 is widely expressed in gastrointestinal epithelial cells124, 125. As a result, SARS-CoV-2 internalization in host cells may be detected in the gastrointestinal system, potentially leading to effective disease and replication126. After oral treatment, Lf stays on the gastrointestinal tract lining, protecting host cells from SARS-CoV-21.

Fusion with the viral envelope

The virus attacks host cells by fusing its envelope to the target cell membrane, an important stage in viral illness. It has been shown that Lf attaches to substances on the virus envelope that mediate the infection procedures and prevent fusion, thus trying to prevent infection127, 128. Various viruses have various binding locations. The hemagglutinin type 1 and neuraminidase type 1 (H1N1) virus binding site is HA, and fusion of Lf with HA has been shown to suppress illness85. The virus coat glycoprotein HA is a crucial component in viral pathogenicity. When Lf binds to HA, it prevents the virus glycoprotein and host cell receptors from merging and causing infection.

Furthermore, they fuse with the F protein on the viral envelope77. RSV, which has been related to severe respiratory diseases in babies, including otitis media and lower respiratory tract involvement (LRTI), is suppressed by Lf129. Lf attaches to the F1 component of the F protein, stopping RSV from entering epithelial cells, limiting the inflammatory reaction induced by RSV, and reducing Hep-2 cell infection. Lf protects the host cell from adenovirus invasion by adhering to the penton base of the virus130. Overall, the ability of Lf to defend against viral diseases is noteworthy. However, it is important to examine whether Lf is similarly efficient in SARS-CoV-2 and discover the attachment sites on SARS-CoV-2. Lf has shown significant, wide-ranging antiviral potency, showing that it might be used to prevent and treat SARS-CoV-214, 131. SARS-Co-V may be inhibited by invading host cells by Lf therapy on HSPGs and ACE288, as illustrated in Figure 2. Lf has a broad spectrum of immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory characteristics that may benefit SARS-CoV-2 therapy and protect against its catastrophic consequences on various organs132, 133.

Blocking viral attachment with host cells

Lf inhibits viral attachment, surface buildup on the host cell, and virus penetration into the cell by operating on cell targets106, 134. Its antiviral action originates in the earliest phases of infection on bare and enveloped viruses, inhibiting the virus from penetrating the host cell132. It inhibits the proliferation of many infections by interfering with the breakdown of the cellular membrane, the sequestration of iron, the prevention of pathogen adherence to host cells, and the creation of biofilms132. The initial step of viral infection, notably in COVID-19, is identifying the first cell attachment receptors. Engaging with these cell receptors is found in glycosaminoglycan heparin sulfate88. Lf can inhibit viral infections. By adhering to cell-surface HSPGs, they have been demonstrated to function as essential cofactors for SARS-CoV-2 disease119, 135. Lf can inhibit the internalization of certain viruses, including the SARS pseudovirus119. Furthermore, Lf has been demonstrated to prevent the entrance of murine coronavirus and human coronaviruses such as hCoV-NL63136, which are similar to SARS-CoV-2. Cathepsin L, a lysosomal peptidase essential for endocytosis, is a cell entrance route utilized by SARS-CoV-2137, 138 and has similarly been shown to be inhibited explicitly by Lf139.

The viral spike protein interacts with the ACE2 receptor and the HSPG attachment factor on the host cell to bind to host cells135, as mentioned in Figure 2. Human coronavirus OC43 HCoV-OC43 virus or SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus fragments were used as SARS-CoV-2 agents. Cell pretreatment and virus inactivation tests were conducted to determine whether Lf interacts with viral adherence via associations with the target cell or the virus. Early cure of rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cells, mostly 1000 g/ml bLf preceding viral illness, lowered the appearance of internal cell viral protein by approximately 80% relative to the H2O exposure reference specimen. The precipitate viral concentration was lowered by approximately 1 log 10 units83. SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus luciferase function was reduced to approximately half that of the H2O-exposed reference after pretreatment of Vero E6 cells with 1000 g/ml bLf. To determine whether Lf directly influences HCoV-OC43 viral fragments, researchers pretreated HCoV-OC43 viruses with 1000 g/ml bLf or the equivalent amount of sterilized H2O (placebo) for 3 hours at 37 °C and then measured the viral titer in rhabdomyosarcoma cells. The virus treated with bLf produced the equivalent quantity of plaques as the H2O-exposed reference at a 106-fold dilution. Since the final concentration in the plaque test was 0.001 g/ml, much beyond its lowest suppressive level (effective concentration (EC50) = 37.9 2.5 g/ml), bLf seemed to have no impact on plaque production. These findings showed that rather than the virus itself, bLf suppresses viral adherence by attaching to target cells83.

Lf inhibits SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus replication in multiple cell lines

The pseudovirus neutralization test is a well-known paradigm for studying viral penetration in target cells. It has been frequently utilized to evaluate the antiviral efficacy of viral entrance antagonists140, 141. To determine whether the antiviral activity of Lfs toward SARS-CoV-2 is cell sort-reliant, researchers tested bLf and hLf in SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus assays in 3 different cell lines: Vero E6 cells, Calu-3 cells, and 293T cells overexpressing ACE2 (293T-ACE2)83. Vero E6 and 293T-ACE2 cells have high levels of ACE2 on the apical membrane but low levels of transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2)142. As a result, SARS-CoV-2 enters such cells via endocytosis and activates endosomal cathepsin L to activate viral spike proteins143. Calu-3, on the other hand, is a human lung epithelial cell line that expresses both ACE2 and TMPRSS2144.

The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein may be activated by TMPRSS2 on the cell membrane, allowing immediate cell entry at the cell surface. E-64d, a cathepsin L blocker, and camostat mesylate, a TMPRSS2 agonist, were used as controls in the SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus invasion tests. Both bLf and hLf, with IC50 values ranging from 26.2 to 49.7 g/ml and 34.4–163.5 g/ml, respectively, reduced SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus entry in all 3 cell lines in a dose-dependent manner. The antiviral test findings from infectious HCoVs show that bLf is more potent than hLf. These findings suggest that Lfs block SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus entrance regardless of cell type83.

Bind to heparin in vitro

According to previous research, LF inhibits SARS-CoV pseudovirus illness in human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK293E)/ACE2-Myc cells by adhering to HSPGs on the surface of the cell88. Furthermore, through its association with the membrane (M) protein, HCoV-NL63 has been demonstrated to use HSPGs as an adherence receptor for virus assembly to target136, 145. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein coreceptors have recently been identified on cell surfaces, facilitating further attachment to the ACE2 receptor135. Based on these observations and the data described above, Lf is proposed to achieve its extensive antiviral effect toward coronaviruses by attaching to HSPGs and thereby passively inhibiting the association between the viral spike protein and ACE2 (Figure 2). They used heparin (Sigma Cat. # H3393) to verify this idea as an HSPG mimic. They used differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) to detect heparin straight attachment to bLf and hLf146. When a ligand binds specifically to a protein, the target protein is generally stabilized, resulting in a higher melting temperature. According to the DSF findings, heparin raised the melting temperature of both bLf and hLf reliant on the amount of the drug, suggesting direct attachment of bLf and hLf to heparin.

Furthermore, bLf has a greater binding affinity for heparin than hLf, as seen by the higher melting temperature, consistent with bLf having more robust antiviral activity than hLF. The associated HCoV-OC43 or human coronavirus-NL63 (HCoV-NL63) membrane of Vero E6 cells or RD cells was measured using immunofluorescence labeling and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) after a viral adherence experiment was performed in the presence of various pairings of heparin and/or Lf. Fluorescent indicators on the membrane of RD cells exposed to the H2O control indicate that the HCoV-OC43 virus had bound to the target cell surface83. Fluorescence markers on the cell surface were decreased in bLf-exposed specimens in a dose-dependent fashion, indicating that bLf prevented viral adherence. The immunofluorescence level showed that heparin administration did not influence viral adhesion. When bLf was pretreated with heparin before being added to the viral attachment test, the fluorescence responses were recovered (86% at 30 g/ml heparin and 19% at 10 g/ml), and the suppression of viral adherence was eliminated83. Because no particular antibodies against HCoV-NL63 were accessible, the immunofluorescence test for HCoV-NL63 was not conducted. Instead, RT–qPCR was used to determine the number of viruses adhering to the cell surface147.

The antiviral action of bLf is mediated by either direct binding to SARS-CoV-2 particles or obscuration of the host cell receptors for these pathogen proteins. More evidence points to a direct interaction between bLf and the spike glycoprotein, which is supported by results from molecular docking and simulations of molecular dynamics. According to the simulation, this identification is extremely likely to take place because of the high number of atomistic contacts found and the permanence of these connections over the simulation. bLf may therefore prevent viral entrance into host cells148.

Synergistic antiviral effect with remdesivir

The World Health Organization (WHO) has approved remdesivir as the most potent antiviral for the current COVID-19 outbreak that SARS-CoV-2 causes. Remdesivir is expected to adhere to SARS-RNA-dependent CoV-2 RNA polymerase with a binding energy of -7.6 kcal/mol, potentially inhibiting149, and the primary viral protease with a binding energy varying from -6.4 to -7.2 kcal/mol150.

Combination medication has been widely investigated for the treatment of oncology, parasitic, and viral infections151, 152. It has many benefits over monotherapies, including delayed advancement of drug opposition, synergistic effectiveness, and fewer side effects due to more secondary medication. Using the HCoV-OC43 antiviral cytopathic effect (CPE) test, the combined therapeutic potential of bLf and remdesivir was investigated. Remdesivir is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved antiviral that inhibits SARS-CoV-2 polymerase. As previously stated, the combination index versus EC50 data of drugs was shown at various combined rates153. The CIs for all combination ratios used in many experiments indicate that bLf had a synergistic antiviral impact with remdesivir in combination treatment.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVE

Because of the direct antiviral activities of Lf and ovotransferrin against various viruses and their antimicrobial actions against a variety of microorganisms that could induce secondary infections in COVID-19 patients154. Their immunomodulatory characteristics enhance antimicrobial reactions while promoting inflammatory resolution, oxidative stress, and excessive inflammatory cytokine manufacturing (particularly IL-6 and TNF-α). The primary recommendation is to use these antimicrobials as soon as signs appear to prevent noncritical situations from becoming serious. However, they may also be used to avoid people at higher risk of infection, where lower doses could be given to reduce infection risk. Because the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is rapidly increasing, oral delivery is the most efficient approach. This is especially true for Lf and ovotransferrin, which have systemic effects after ingestion. Pasteurized entire milk has been shown to influence the shifting of phagocytes from M1 to M2. Other than those found in ovotransferrin, many peptides in egg white have shown antioxidant and ACE-inhibitory consequences155, 156. Individuals who are extremely sick and on ventilators, on the other hand, may require extra caution with the technique. Lf might be used intravenously or through nebulization. In this case, liposomal bLf nebulizer treatment is available. Because of its availability and low cost, this antibiotic is appealing as a treatment alternative (in comparison to some other medicines, such as remdesivir).

Therapy for latent or chronic viral diseases, common in immunocompromised patients, is potentially a viable use of Lf in conjunction with certain chemotherapeutic drugs. Lf has been shown to work in concert with complement157 and immunoglobulin158. These findings show that Lf is a complicated and multipurpose protein that plays a role in natural immunity. That research into its antimicrobial properties must always be considered in the context of a larger view of host resistance. Lf antibacterial action results from a protracted evolutionary procedure in which a molecule operates in a complicated picture. This impacts cytokine synthesis, immune cell function, and overall inflammatory reaction modulation159. To summarize, Lf should be viewed as a major element in mammalian innate immunity and as a polyvalent regulator that achieves its goal by associating with a variety of factors engaged in infectious or inflammatory activities82. There is little question that LF supplementation is an interesting area for further investigation however, the findings of this study do not allow for a firm judgment regarding its potential advantages as a support treatment160.

CONCLUSION

The explosive growth of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic has become a significant worldwide health issue. As a result, effective therapeutic medicines are needed to guard against and cure SARS-CoV-2. Lf has demonstrated strong antiviral efficacy throughout a broad range, indicating that it might be utilized to cure and treat SARS-CoV-2. For instance, Lf therapy of ACE2 and HSPGs can inhibit SARS-CoV from invading target cells. Lf has many immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory properties that may help treat SARS-CoV-2 and limit its catastrophic consequences on a variety of different organs. Additionally, Lf has a superior safety profile than other antiviral medications.

Consequently, using Lf to cure COVID-19 may be promising and deserves additional research. Lf may also adhere to viral fragments actively, such as HCV, and keep them away from particular sites. In HIV, Lf limits viral entry and suppresses virus growth once it enters the cell. SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV share 80% of their genomes, RBD structures, and cellular receptors, and the RBD 1 helix attaches to the PD of ACE2 through polar activity. Although the three-dimensional structures of bovine and hLf are similar, they are not identical. The most common Lf found in breast milk is apolipoprotein. The existence of (limited quantities of) bicarbonate affects the capacity of Lf to bind iron.

Substantial cationic peptide sequences at the N-terminus of both hLf and bLf contribute to several important interaction characteristics. The total number of binding domains in hLf was the maximum for human lymphoblast T cells. The bactericidal properties of Lf have also been discovered. This bactericidal action is not iron reliant and may be triggered in a variety of ways. The ability of Lf to bind endotoxin is considered important in immunomodulation. LPS (also known as endotoxin) is a constituent of the bacterial outer layer. When TLR-4 recognizes this "pathogen-associated molecular pattern," it induces a range of immunological responses in leukocytes and platelets. Lf gene silencing has been related to many molecular events in cancer cells, including regulator and gene hypermethylation, as well as actual gene sequence alterations. Lf binds to several viruses that are particularly sensitive. Antiviral activity can also be achieved by linking to target cell molecules, which the virus uses as a receptor or coreceptor. Lf protects ob/ob mouse liver tissues against oxidative and ER stress.

Abbreviations

ACE2, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme2; Asn, Asparagine; CD4+, Cluster of Differentiation 4+; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease-2019; Cu2+, copper; CPE, Cytopathic Effect; CpG, Cytosines followed by Guanine residues; DSF, Differential Scanning Fluorimetry; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; EC50, Effective Concentration 50; E. coli, Escherichia coli; ER, Endoplasmic Reticulum; ERK, Extracellular Signal-Regulated Protein Kinase; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; GAGs, Glycosaminoglycans; HA, hemagglutinin; H1N1, Hemagglutinin type 1 and Neuraminidase type 1; HCoV-NL63, Human Coronavirus-NL63; HEK, Human Embryonic Kidney; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus; HSV, Herpes Simplex Virus; HIF-lα, Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 alpha; HSPGs, Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans; HUVECs, Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells; IC 50, Inhibitory Concentration 50; IL, Interleukin; Lf, Lactoferrin; bLf, Bovine Lf; hLf, human Lf; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide; NAFLD, Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease; NK, Natural Killer; NSAIDs, Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs; NETs, Neutrophil Extracellular Traps; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; PD, Peptidase Domain; RSV, Respiratory Syncytial Virus; RBD, Receptor-Binding Domain; RT–PCR, Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction; p-eIF2, phosphorylation of the eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2; p-NF-κB, phosphorylation of the Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; SARS, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TMPRSS2, Transmembrane protease serine 2; TNF-α, Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; VEGF, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; WHO, World Health Organization.

Acknowledgments

The authors concede the support of the Cholistan University of Veterinary & Animal Sciences-Bahawalpur, Pakistan, during the write-up.

Author’s contributions

KN conceived the original idea and designed the outline of the study. SR and FS equally contributed to and wrote the 1st draft of the manuscript. KN revised the whole manuscript and formatted it accordingly. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

-

Wang

B.,

Timilsena

Y.P.,

Blanch

E.,

Adhikari

B.,

Lactoferrin: Structure, function, denaturation and digestion. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition.

2019;

59

(4)

:

580-96

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Mikulic

N.,

Uyoga

M.A.,

Mwasi

E.,

Stoffel

N.U.,

Zeder

C.,

Karanja

S.,

Iron absorption is greater from Apo-Lactoferrin and is similar between Holo-Lactoferrin and ferrous sulfate: stable iron isotope studies in Kenyan infants. The Journal of Nutrition.

2020;

150

(12)

:

3200-7

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Majka

G.,

Pilarczyk-Zurek

M.,

Baranowska

A.,

Skowron

B.,

Strus

M.,

Lactoferrin Metal Saturation-Which Form Is the Best for Neonatal Nutrition?. Nutrients.

2020;

12

(11)

:

3340

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Fais

R.,

Di Luca

M.,

Rizzato

C.,

Morici

P.,

Bottai

D.,

Tavanti

A.,

The N-terminus of human lactoferrin displays anti-biofilm activity on Candida parapsilosis in lumen catheters. Frontiers in Microbiology.

2017;

8

:

2218

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Kumar

B.G.,

Mattad

S.,

Comprehensive analysis of lactoferrin N-glycans with site-specificity from bovine colostrum using specific proteases and RP-UHPLC-MS/MS. International Dairy Journal.

2021;

119

:

104999

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Campione

E.,

Cosio

T.,

Rosa

L.,

Lanna

C.,

Di Girolamo

S.,

Gaziano

R.,

Lactoferrin as protective natural barrier of respiratory and intestinal mucosa against coronavirus infection and inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

2020;

21

(14)

:

4903

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Xiong

L.,

Boeren

S.,

Vervoort

J.,

Hettinga

K.,

Effect of milk serum proteins on aggregation, bacteriostatic activity and digestion of lactoferrin after heat treatment. Food Chemistry.

2021;

337

:

127973

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Niaz

B.,

Saeed

F.,

Ahmed

A.,

Imran

M.,

Maan

A.A.,

Khan

M.K.,

Lactoferrin (LF): a natural antimicrobial protein. International Journal of Food Properties.

2019;

22

(1)

:

1626-41

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Woodman

T.,

Strunk

T.,

Patole

S.,

Hartmann

B.,

Simmer

K.,

Currie

A.,

Effects of lactoferrin on neonatal pathogens and Bifidobacterium breve in human breast milk. PLoS One.

2018;

13

(8)

:

e0201819

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Acosta-Smith

E.,

Viveros-Jiménez

K.,

Canizalez-Román

A.,

Reyes-Lopez

M.,

Bolscher

J.G.,

Nazmi

K.,

Bovine lactoferrin and lactoferrin-derived peptides inhibit the growth of Vibrio cholerae and other Vibrio species. Frontiers in Microbiology.

2018;

8

:

2633

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Rascón-Cruz

Q.,

Espinoza-Sánchez

E.A.,

Siqueiros-Cendón

T.S.,

Nakamura-Bencomo

S.I.,

Arévalo-Gallegos

S.,

Iglesias-Figueroa

B.F.,

Lactoferrin: A glycoprotein involved in immunomodulation, anticancer, and antimicrobial processes. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland).

2021;

26

(1)

:

205

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Bezault

J.,

Bhimani

R.,

Wiprovnick

J.,

Furmanski

P.,

Human lactoferrin inhibits growth of solid tumors and development of experimental metastases in mice. Cancer Research.

1994;

54

(9)

:

2310-2

.

-

Zhang

J.,

Ling

T.,

Wu

H.,

Wang

K.,

Re-expression of Lactotransferrin, a candidate tumor suppressor inactivated by promoter hypermethylation, impairs the malignance of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine.

2015;

44

(8)

:

578-84

.

View Article Google Scholar -

van der Strate

B.W.,

Beljaars

L.,

Molema

G.,

Harmsen

M.C.,

Meijer

D.K.,

Antiviral activities of lactoferrin. Antiviral Research.

2001;

52

(3)

:

225-39

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Elnagdy

S.,

AlKhazindar

M.,

The potential of antimicrobial peptides as an antiviral therapy against COVID-19. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science.

2020;

3

(4)

:

780-2

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Weimer

K.E.,

Roark

H.,

Fisher

K.,

Cotten

C.M.,

Kaufman

D.A.,

Bidegain

M.,

Breast milk and saliva lactoferrin levels and postnatal cytomegalovirus infection. American Journal of Perinatology.

2021;

38

(10)

:

1070-7

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Sultana

C.,

Roşca

A.,

Grancea

C.,

In the backstage of lactoferrin derived peptides' antiviral activity. ROMANIAN ARCHIVES OF MICROBIOLOGY AND IMMUNOLOGY.

2018;

77

(3)

:

213-21

.

-

Ahmed

K.A.,

Saikat

A.S.,

Moni

A.,

Kakon

S.A.,

Islam

M.R.,

Uddin

M.J.,

Lactoferrin: potential functions, pharmacological insights, and therapeutic promises. J Adv Biotechnol Exp Ther.

2021;

4

(2)

:

223

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Wang

Y.Z.,

Zhao

Y.Q.,

Wang

Y.M.,

Zhao

W.H.,

Wang

P.,

Chi

C.F.,

Anti-oxidant peptides from Antarctic Krill (Euphausia superba) hydrolysate: Preparation, identification and cytoprotection on H2O2-induced oxidative stress. Journal of Functional Foods.

2021;

86

:

104701

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Zakharova

E.T.,

Sokolov

A.V.,

Pavlichenko

N.N.,

Kostevich

V.A.,

Abdurasulova

I.N.,

Chechushkov

A.V.,

Erythropoietin and Nrf2: key factors in the neuroprotection provided by apo-lactoferrin. Biometals.

2018;

31

(3)

:

425-43

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Rezaeimanesh

N.,

Farzi

N.,

Pirmanesh

S.,

Emami

S.,

Yadegar

A.,

Management of multi-drug resistant Helicobacter pylori infection by supplementary, complementary and alternative medicine; a review. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from Bed To Bench.

2017;

10

:

8-14

.

-

Farid

A.S.,

El Shemy

M.A.,

Nafie

E.,

Hegazy

A.M.,

Abdelhiee

E.Y.,

Anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and hepatoprotective effects of lactoferrin in rats. Drug and Chemical Toxicology.

2021;

44

(3)

:

286-93

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Goulding

D.A.,

Vidal

K.,

Bovetto

L.,

O'Regan

J.,

O'Brien

N.M.,

O'Mahony

J.A.,

The impact of thermal processing on the simulated infant gastrointestinal digestion, bactericidal and anti-inflammatory activity of bovine lactoferrin - An in vitro study. Food Chemistry.

2021;

362

:

130142

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Chang

R.,

Ng

T.B.,

Sun

W.Z.,

Lactoferrin as potential preventative and adjunct treatment for COVID-19. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents.

2020;

56

(3)

:

106118

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Wang

Y.,

Wang

P.,

Wang

H.,

Luo

Y.,

Wan

L.,

Jiang

M.,

Lactoferrin for the treatment of COVID-19 (Review). Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine.

2020;

20

(6)

:

272

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Mann

J.K.,

Ndung'u

T.,

The potential of lactoferrin, ovotransferrin and lysozyme as antiviral and immune-modulating agents in COVID-19. Future Virology.

2020;

15

(9)

:

609-24

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Alpogan

O.,

Karakucuk

S.,

Lactoferrin: The Natural Protector of the Eye against Coronavirus-19. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation.

2021;

29

(4)

:

751-2

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Kondapi

A.K.,

Targeting cancer with lactoferrin nanoparticles: recent advances. Nanomedicine (London).

2020;

15

(21)

:

2071-83

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Haridas

M.,

Anderson

B.F.,

Baker

E.N.,

Structure of human diferric lactoferrin refined at 2.2 A resolution. Acta Crystallographica. Section D, Biological Crystallography.

1995;

51

(Pt 5)

:

629-46

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Wang

M.,

Xu

J.,

Han

T.,

Tang

L.,

Effects of theaflavins on the structure and function of bovine lactoferrin. Food Chemistry.

2021;

338

:

128048

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Parc

A.L.,

Karav

S.,

Rouquié

C.,

Maga

E.A.,

Bunyatratchata

A.,

Barile

D.,

Characterization of recombinant human lactoferrin N-glycans expressed in the milk of transgenic cows. PLoS One.

2017;

12

(2)

:

e0171477

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Spik

G.,

Coddeville

B.,

Mazurier

J.,

Bourne

Y.,

Cambillaut

C.,

Montreuil

J.,

Primary and three-dimensional structure of lactotransferrin (lactoferrin) glycans. Lactoferrin. Springer; 1994:21-32. .

View Article Google Scholar -

Zlatina

K.,

Galuska

S.P.,

The N-glycans of lactoferrin: more than just a sweet decoration. Biochemistry and Cell Biology.

2021;

99

(1)

:

117-27

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Soboleva

S.E.,

Sedykh

S.E.,

Alinovskaya

L.I.,

Buneva

V.N.,

Nevinsky

G.A.,

Cow milk lactoferrin possesses several catalytic activities. Biomolecules.

2019;

9

(6)

:

208

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Steijns

J.M.,

van Hooijdonk

A.C.,

Occurrence, structure, biochemical properties and technological characteristics of lactoferrin. British Journal of Nutrition.

2000;

84

(S1)

:

11-7

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Singh

A.,

Ahmad

N.,

Varadarajan

A.,

Vikram

N.,

Singh

T.P.,

Sharma

S.,

Lactoferrin, a potential iron-chelator as an adjunct treatment for mucormycosis - A comprehensive review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules.

2021;

187

:

988-98

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Omar

O.M.,

Assem

H.,

Ahmed

D.,

Abd Elmaksoud

M.S.,

Lactoferrin versus iron hydroxide polymaltose complex for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Pediatrics.

2021;

180

(8)

:

2609-18

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Cutone

A.,

Colella

B.,

Pagliaro

A.,

Rosa

L.,

Lepanto

M.S.,

Bonaccorsi di Patti

M.C.,

Native and iron-saturated bovine lactoferrin differently hinder migration in a model of human glioblastoma by reverting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-like process and inhibiting interleukin-6/STAT3 axis. Cellular Signalling.

2020;

65

:

109461

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Superti

F.,

Lactoferrin from bovine milk: a protective companion for life. Nutrients.

2020;

12

(9)

:

2562

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Ward

P.P.,

Zhou

X.,

Conneely

O.M.,

Cooperative interactions between the amino- and carboxyl-terminal lobes contribute to the unique iron-binding stability of lactoferrin. The Journal of Biological Chemistry.

1996;

271

(22)

:

12790-4

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Legrand

D.,

van Berkel

P.H.,

Salmon

V.,

van Veen

H.A.,

Slomianny

M.C.,

Nuijens

J.H.,

The N-terminal Arg2, Arg3 and Arg4 of human lactoferrin interact with sulphated molecules but not with the receptor present on Jurkat human lymphoblastic T-cells. The Biochemical Journal.

1997;

327

(Pt 3)

:

841-6

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Rosa

L.,

Cutone

A.,

Lepanto

M.S.,

Scotti

M.J.,

Conte

M.P.,

Paesano

R.,

Physico-chemical properties influence the functions and efficacy of commercial bovine lactoferrins. Biometals.

2018;

31

(3)

:

301-12

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Rosa

L.,

Cutone

A.,

Lepanto

M.S.,

Paesano

R.,

Valenti

P.,

Lactoferrin: a natural glycoprotein involved in iron and inflammatory homeostasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

2017;

18

(9)

:

1985

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Mallaki

M.,

Hosseinkhani

A.,

Taghizadeh

A.,

Hamidian

G.,

Paya

H.,

The Effect of Bovine Lactoferrin and Probiotic on Performance and Health Status of Ghezel Lambs in Preweaning Phase. Iranian Journal of Applied Animal Science.

2021;

11

(1)

:

101-10

.

-

Preeti

J.K.R.,

Suman

M.,

Kannegundla

U.,

Thakur

M.,

Kumar

R.,

A multifunctional bioactive protein: Lactoferrin. The Pharma Innovation Journal.

2018;

7

(4)

:

75--79

.

-

van Berkel

P.H.,

Geerts

M.E.,

van Veen

H.A.,

Mericskay

M.,

de Boer

H.A.,

Nuijens

J.H.,

N-terminal stretch Arg2, Arg3, Arg4 and Arg5 of human lactoferrin is essential for binding to heparin, bacterial lipopolysaccharide, human lysozyme and DNA. The Biochemical Journal.

1997;

328

(Pt 1)

:

145-51

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Drago-Serrano

M.E.,

Campos-Rodriguez

R.,

Carrero

J.C.,

de la Garza

M.,

Lactoferrin and peptide-derivatives: antimicrobial agents with potential use in nonspecific immunity modulation. Current Pharmaceutical Design.

2018;

24

(10)

:

1067-78

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Li

Y.Q.,

Guo

C.,

A Review on Lactoferrin and Central Nervous System Diseases. Cells.

2021;

10

(7)

:

1810

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Giansanti

F.,

Panella

G.,

Arienzo

A.,

Leboffe

L.,

Antonini

G.,

Nutraceutical peptides from lactoferrin. Journal of Advances in Dairy Research.

2018;

6

(1)

:

199

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Trovero

M.F.,

Scavone

P.,

Platero

R.,

de Souza

E.M.,

Fabiano

E.,

Rosconi

F.,

Herbaspirillum seropedicae differentially expressed genes in response to iron availability. Frontiers in Microbiology.

2018;

9

:

1430

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Zhang

Y.,

Pu

C.,

Tang

W.,

Wang

S.,

Sun

Q.,

Gallic acid liposomes decorated with lactoferrin: Characterization, in vitro digestion and antibacterial activity. Food Chemistry.

2019;

293

:

315-22

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Sun

C.,

Li

Y.,

Cao

S.,

Wang

H.,

Jiang

C.,

Pang

S.,

Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of bovine lactoferricin derivatives with symmetrical amino acid sequences. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

2018;

19

(10)

:

2951

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Liu

Z.S.,

Lin

C.F.,

Lee

C.P.,

Hsieh

M.C.,

Lu

H.F.,

Chen

Y.F.,

A Single Plasmid of Nisin-Controlled Bovine and Human Lactoferrin Expressing Elevated Antibacterial Activity of Lactoferrin-Resistant Probiotic Strains. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland).

2021;

10

(2)

:

120

.