Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically restricted adolescents’ lives. We used nationwide Norwegian survey data from 2014–2021 (N = 227,258; ages 13–18) to examine psychosocial outcomes in adolescents before and during the pandemic. Multilevel models revealed higher depressive symptoms and less optimistic future life expectations during the pandemic, even when accounting for the measures’ time trends. Moreover, alcohol and cannabis use decreased, and screen time increased. However, the effect sizes of all observed changes during the pandemic were small. Overall, conduct problems and satisfaction with social relationships remained stable. Girls, younger adolescents and adolescents from low socio-economic backgrounds showed more adverse changes during the pandemic. Estimated changes in psychosocial outcomes varied little with municipality infection rates and restrictions. These findings can inform means and interventions to reduce negative psychological outcomes associated with the pandemic and identify groups that need particular attention during and after the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. Since then, drastic measures to prevent the spread of the pandemic have been implemented worldwide. The imposed restrictions, such as school closures, physical distancing and restrictions on recreational activities, raise concerns about adolescents’ well-being1,2. Knowledge about psychosocial consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic is rapidly accumulating; however, there is a scarcity of large-scale, population-based, repeated cross-sectional studies providing comprehensive assessments of psychosocial factors before and during the pandemic. Moreover, even though some information is available about adolescents’ psychosocial well-being during the initial months of the pandemic3,4,5, the long-term effects are less known. To address this issue, we use nationwide Norwegian data from 227,258 adolescents before and one year into the pandemic. By applying multilevel societal growth curves6 that enable us to disentangle the sudden changes during the pandemic from long-term time trends, we examine (1) changes in psychosocial outcomes during the pandemic, (2) whether disadvantaged groups are particularly vulnerable to these changes and (3) whether these changes vary with geographical variations in infection rates and restrictions.

We examine how the pandemic has potentially affected adolescents’ lives in five key life domains: social relationships, mental health, conduct problems and substance use, physical activity and screen time, and future life expectations. Concerning social relationships, adolescents’ social lives have substantively changed during the pandemic due to infection control measures such as school closures and physical distancing7. Consequently, peer relationships may be disrupted in this time of social deprivation. In fact, one of the greatest pandemic-related concerns reported by adolescents is not feeling connected to friends4. The pandemic may also have affected relationships within the family: financial insecurity, caregiving burden and confinement-related stress may adversely affect parent–child relationships8. However, changes in family routines and the increased amount of time and attention spent within the family may also have had positive effects for some children and adolescents9.

It has been suggested that the pandemic has led to increasing mental health problems among youth because of the unique combination of social isolation, economic recession and disruptions in mental health care services1,2. Large-scale studies in several countries have indicated that early in the pandemic, mental health problems increased among adults10,11,12,13. Moreover, data from 12 longitudinal studies and one repeated cross-sectional study have shown that adolescent depressive symptoms increased from before to during the pandemic14,15. However, these longitudinal studies do not disentangle the effects of the pandemic from normative ageing processes in adolescence. To illustrate, a Norwegian longitudinal study indicated that increases in depression and anxiety during the pandemic were caused by adolescents getting older rather than by effects of the pandemic3. More research using large-scale repeated cross-sectional studies is therefore needed to provide information on the effect of the pandemic on adolescent mental health.

Concerning substance use, the pandemic limits situations where adolescents consume alcohol and other drugs, such as unsupervised parties. In line with this reasoning, repeated cross-sectional surveys in Iceland have shown that adolescent alcohol intoxication and cigarette smoking declined during the pandemic15. In contrast, a Canadian study assessing drug consumption in adolescents retrospectively indicated increased alcohol and cannabis use16. Regarding conduct problems, crimes committed by young people in the United States seemed to decrease during the pandemic17. We follow this line of research by examining changes in substance use and conduct problems from before to one year into the pandemic.

Restrictions during the pandemic may also lead to a decrease in physical activity for adolescents, which in turn may have long-term negative health consequences18. A multi-wave survey in China seems to confirm these concerns by finding reduced physical activity in children and adolescents due to the pandemic19. However, a longitudinal study on children and teens in Germany found that even though sports activity declined in the beginning of the pandemic, habitual physical activities increased, thereby leading to an overall increase in physical activity5. Both studies also found that recreational screen time increased5,19. We therefore examine changes during the pandemic in physical activity and screen time among Norwegian adolescents.

Finally, the pandemic may affect adolescents’ expectations concerning their future life opportunities. The pandemic may have challenged adolescents’ basic beliefs about living in a safe and controllable world. Moreover, the economic recession triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to hit those who are in the initial phase of their labour market career the hardest20. Adolescents might thus be more pessimistic about their future prospects, but empirical data on this issue are scarce.

Social disparities typically increase in times of crisis21, and European and US studies have documented that the less educated and the poor are more severely affected economically by the COVID-19 pandemic22,23. As a consequence of increasing economic hardship, adolescents from low socio-economic backgrounds may be disproportionately affected by the pandemic in several psychosocial domains, with a higher risk of living in crowded households, increased family stress and adverse health effects during the pandemic24,25. We therefore aim to examine whether social disparities among adolescents have widened during the pandemic in a variety of life domains.

The adverse effects of the pandemic may also vary with other sociodemographic factors. For example, adolescent girls show more symptoms of anxiety and depression and ruminative coping styles than boys26 and may be affected more by the pandemic psychosocially. One repeated cross-sectional study and two longitudinal studies have provided evidence that the pandemic has led to increasing gender disparities in mental health problems in adolescents4,15 and adults10. With the exception of one study indicating no gender differences in pandemic effects on substance use15, studies examining whether girls are more severely affected by the pandemic in psychosocial domains other than mental health are lacking. Finally, pandemic effects may differ according to age, and Icelandic data indicate that older adolescents may be less affected by the pandemic than younger adolescents15. Research is needed to examine whether these findings can be generalized to other geographic contexts.

COVID-19 infection rates and the extent of the restrictions imposed vary considerably both across countries and across smaller geographical units within countries, such as municipalities27. It is therefore important to examine to what degree infection rates and restrictions affect adolescents’ psychosocial well-being. However, we lack studies that examine how regional infection rates and restriction severity are related to psychosocial well-being in adolescents. The present study therefore assesses how infection rates and infection control measures at the municipality level predict changes in psychosocial variables from before to during the pandemic.

Despite the relatively low COVID-19-related death rate in Norway, infection control measures have been similar to those in other European countries27 and include mandatory physical distancing and severe restrictions on recreational activities. Norwegian schools were closed on 12 March 2020, and digital teaching was implemented. Junior and senior high schools reopened on 11 May 2020; however, national restrictions at schools were implemented, including smaller class sizes, physical distancing measures and partial digital schooling from home. National school restrictions were adjusted repeatedly according to infection rates, but schools were not closed again nationwide. National restrictions did not differ substantially between junior and senior high schools. In addition to national restrictions, municipalities could implement local restrictions if necessary. With 894 infections per 100,000 inhabitants in the three-month period of the 2021 data collection (January to March 2021), COVID-19 infection rates in Norway were of the same magnitude or somewhat lower than those in Finland (768 per 100,000), Denmark (1,102 per 100,000) and the United Kingdom (1,270 per 100,000), while infection rates were substantially higher in other European countries, such as Spain (2,715 per 100,000) and France (2,961 per 100,000)27.

In summary, there is a need for methodologically sound, large-scale, population-based studies examining changes in key life domains during the long-lasting COVID-19 pandemic for adolescents. Using a nationwide dataset comprising 227,258 adolescents, we address the following three questions. What are the psychosocial changes for adolescents one year after the onset of the pandemic? Are the changes disproportionately large for adolescents from disadvantaged backgrounds? Do the changes vary according to geographical variations in infection rates and restrictions? Our data and analyses cannot isolate the causal effect of the pandemic itself, but they can reveal the changes in psychosocial outcomes that have been observed during the pandemic. During the pandemic, we expect to see adverse changes in social relationships, mental health and future life expectations. In contrast, we expect to find a decrease in substance use and conduct problems. We expect screen time to have increased, whereas expected changes in physical activity during the pandemic are unclear. Despite limited evidence for adolescents, we expect to find disproportionate changes in psychosocial outcomes in girls, adolescents in poor families and adolescents with low parental education. Finally, we expect changes in psychosocial outcomes to vary with the infection rates and restriction measures on the municipality level.

Results

We used data from 227,258 adolescents from 157 municipalities in Norway, collected between 2014 and 2021. In 2021, 86,597 adolescents participated. Because municipalities typically participate every third or fourth year in the data collection scheme, the number of municipalities included before 2021 was the highest in 2018, 2017 and 2015 (Table 1). Response rates were high and ranged from 77% in 2021 to 85% in 2017, except for the year 2020: the response rate in 2020 was considerably lower (65%) because a substantial number of students were scheduled to participate in the survey after 12 March, when schools were closed due to the pandemic and the data collection was discontinued.

Tables 1 and 2 present descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for all study variables across all data collection years. To provide a scaling that is easily interpretable and allows comparison across variables, all psychosocial outcomes were scaled as percent of maximum possible (POMP) scores, which can be interpreted as the percentage of the maximum possible scores achievable on the scale28. On average, adolescents were highly satisfied with their social relationships, as they indicated satisfaction with both peer and parental relationships above 80% of the maximum score possible in all years (Table 1). Across all years, adolescents scored on average on the lower end of the scale for indicators of mental health. Adolescents scored relatively high on physical activity and daily screen time, with an average of 67% and 72% of the maximum possible scores across all years, respectively. Across all years, 70% of the adolescents reported expecting a happy life in the future. Concerning socio-economic status, 19% of the adolescents indicated that neither of their parents had higher education, and 5% perceived their family’s economic status to be poor.

Changes during the COVID-19 pandemic

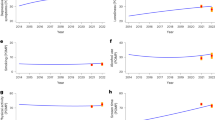

In the first set of analyses, we estimated the potential effect of the pandemic (that is, the change observed during the pandemic) for each outcome variable by using multilevel societal growth curves for all municipalities. To estimate the potential effect of the pandemic, we included a dummy variable indicating participation in 2021. The regression coefficient for the dummy provides an estimate of the deviation of the outcome variable during the pandemic over and above the general trend as represented by the societal growth curves. Parental education, gender and age were included as covariates. We did not control for family poverty, because parts of the potential adverse psychosocial effects of the pandemic may be due to increasing financial difficulties in some families. Including this variable as a covariate would therefore have resulted in removing parts of the potential effect of the pandemic. Table 3 presents growth parameters of the societal growth curves and the estimated effect of the pandemic, and Fig. 1 presents the results graphically. Satisfaction with peer relationships did not change substantially from 2014 to 2021, as indicated by statistically non-significant linear and quadratic slopes (Table 3). Satisfaction with parental relationships showed a statistically significant linear increase across all years (Table 3). Moreover, the analyses revealed no deviations in 2021 from the general trend line in either peer or parental relationships during the pandemic, as the estimates of the potential effects of the pandemic were not statistically significant (Table 3). Depressive symptoms were 2.13 percentage points higher than expected in 2021 on a POMP scale (β = 2.13; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.99 to 3.27; Table 3). To illustrate the size of this statistically significant change during the pandemic, we re-estimated the societal growth curve with standardized symptom scores and calculated a standardized effect size of 0.08 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.12), which is considered a small effect29. Loneliness increased linearly from 2014 and thereafter, including under the pandemic in 2021. However, no statistically significant additional adverse change in loneliness during the pandemic was observed (Table 3). Concerning substance use, there was no statistically significant change in smoking behaviour during the pandemic. In contrast, adolescents reported statistically significantly decreased levels of alcohol intoxication and less use of cannabis in 2021, relative to what would have been expected according to the trend line, with decreases of 2.58 (95% CI, −4.41 to −0.74) and 0.87 (95% CI, −1.52 to −0.22) POMP scores, respectively (Table 3). Standardized effect sizes also showed small effects of −0.08 (95% CI, −0.13 to −0.02) and −0.06 (95% CI, −0.10 to −0.02) for alcohol intoxication and cannabis use, respectively. Physical activity decreased slightly through all years, and we did not see a statistically significant change during the pandemic (Table 3). However, in 2021, screen time increased by 1.69 POMP scores (95% CI, 0.65 to 2.72) over an already increasing general time trend, with a small standardized effect of 0.07 (95% CI, 0.03 to 0.12; Table 3). Finally, adolescents had less positive future expectations during the pandemic, compared with what would be expected according to the general time trend. The decrease by 2.36 POMP scores (95% CI, −4.12 to −0.60) with a standardized effect of −0.05 (95% CI, −0.09 to −0.01) indicated a small change during the pandemic (Table 3). We re-estimated all societal growth curve analyses by additionally controlling for perceived family poverty, with no substantial change in the results (Supplementary Table 7).

a–k, In each plot, the blue line indicates the time trends from 2014 to 2021 as estimated by societal growth curves. The red dot represents the average estimated value during the pandemic in January to March 2021, and the 95% CI is represented by orange bars. The data from 2020 were collected before the lockdown due to the COVID-19 outbreak (that is, before 12 March 2020). Societal growth curves and estimated values during the pandemic are presented for satisfaction with peer relationships (a), satisfaction with parental relationships (b), depressive symptoms (c), loneliness (d), smoking behaviour (e), alcohol intoxication (f), cannabis use (g), conduct problems (h), physical activity (i), screen time (j) and expecting a happy future (k). Data from N = 227,258 adolescents from the nationwide Norwegian Ungdata surveys were used in the analyses.

Individual-level interaction effects

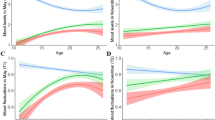

Next, we examined whether adolescents from disadvantaged backgrounds showed signs of being disproportionally affected by the pandemic. For this purpose, we tested whether the potential pandemic effect indicating changes above the general time trend was moderated by low parental education and perceived poverty, while controlling for age and gender. We additionally controlled for parental education in moderation analyses with perceived poverty. Figure 2 shows the results of the interaction analyses from multilevel models by graphically presenting point estimates of pandemic effects according to sociodemographic characteristics; the detailed results are displayed in Supplementary Tables 1–4. The results in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1 show that adolescents with low parental education seemed to be more affected in the domains of social relationships and mental health: peer and parental relationships decreased more and depressive symptoms and loneliness increased more than among adolescents with higher parental education. For example, depressive symptoms increased during the pandemic by 3.81 POMP scores among adolescents with low parental education and by only 2.35 POMP scores among adolescents with higher parental education. This difference of 1.56 POMP scores was statistically significant, as indicated by the orange bar between the point estimates (Fig. 2; see also Supplementary Table 1). There were no statistically significant moderation effects of parental education on drug use and conduct problems. In contrast, parental education moderated changes in physical activity, screen time and future life expectations during the pandemic. Whereas physical activity decreased among those with low parental education, it increased among other adolescents. Screen time increased less among those with low parental education than among other adolescents, and the decline in optimistic future life expectations was greater in adolescents with low parental education.

a–d, The blue and red dots indicate point estimates of the effect of the pandemic for specific groups of adolescents, as estimated by conditional effects analysis. The orange bars represent statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between the estimated pandemic effects for different groups of adolescents. Tests of significance were provided by interaction analyses in multilevel models. The effects of the pandemic were estimated at different levels of parental education (a) and perceived family poverty (b) and for different genders (c) and ages (d). Data from N = 227,258 adolescents from the nationwide Norwegian Ungdata surveys were used in the analyses.

Similar results were found when examining perceived family poverty (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2), where moderation analyses indicated more severe adverse effects on parental relationships, depressive symptoms and loneliness among those who perceived their family’s economic situation to be difficult. Additionally, adolescents who perceived their family to be poor showed a smaller decrease in smoking, cannabis use and conduct problems than other adolescents. As was found for parental education, physical activity declined more among adolescents in poor families, whereas no statistically significant differences between adolescents in poor families and other adolescents were found for screen time and future life expectations.

When examining moderator effects for gender (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3), we found that satisfaction with peer relationships and parental relationships decreased more for girls than for boys, whereas girls’ depressive symptoms increased more than boys’. Moreover, smoking, alcohol intoxication and conduct problems decreased less for girls than for boys. Furthermore, physical activity increased less and screen time increased more for girls than for boys. Only loneliness showed an opposite trend, with boys reporting a greater increase in feeling lonely during the pandemic than girls. The largest gender differences were observed for satisfaction with parental relationships and screen time, with differences of about 3 POMP scores between boys and girls. On the basis of the moderation analyses, we conducted post hoc analyses where we estimated the 95% CIs of the estimated conditional effects of the pandemic for girls and boys separately. The results indicated statistically significant estimated effects of the pandemic for girls for satisfaction with peer and parental relationships, depressive symptoms, cannabis use, conduct problems, screen time and future life expectations, as the 95% CIs did not include 0. Statistically significant pandemic effects for boys were found for depressive symptoms, loneliness, alcohol intoxication, cannabis use and future life expectations.

Finally, for all variables but cannabis use, older age was related to less adverse estimated effects of the pandemic, with the largest age differences for depressive symptoms, loneliness and future life expectations (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 4). Post hoc analyses showed that the estimated conditional effects for 13-year-olds were statistically significant for all outcomes except smoking behaviour and physical activity. In contrast, among 18-year-olds, statistically significant estimated effects of the pandemic were observed only for loneliness, smoking behaviour, alcohol intoxication and physical activity.

Municipality-level interaction effects

In the final set of multilevel analyses, we examined whether infection rates at the municipality level and the number of weeks with strict local restrictions moderated the estimated effect of the pandemic by including cross-level interactions with these two variables in the model. We also controlled for age, gender and parental education. The results showed that municipality-level infection rates were not statistically significantly related to changes from before to during the pandemic for any of the assessed psychosocial variables (Supplementary Table 5). When we examined restrictions, we found a statistically significant interaction effect only for smoking, indicating that for each week with additional restrictions in schools in a municipality, smoking behaviour decreased by 0.15 POMP scores more during the pandemic than in municipalities without such restrictions (Supplementary Table 6).

Discussion

By using a nationwide sample of 227,258 adolescents with measures before and one year into the COVID-19 pandemic, this study provides insight into the changes observed during the pandemic in Norway, and therefore the potential effects of the pandemic, on key psychosocial aspects in adolescents’ lives. By using multilevel societal growth curves to adjust for general time trends, we show that depressive symptoms and screen time increased. Moreover, alcohol intoxication and cannabis use decreased, and adolescents had less optimistic expectations about their future lives. Most strikingly, we see a consistent association between low parental education/perceived family poverty and adverse estimated effects of the pandemic in several domains of adolescents’ lives. In addition, girls and younger adolescents showed more negative changes during the pandemic than boys and older adolescents. Finally, COVID-19 infection rates on the municipality level were not related to changes in adolescents’ psychosocial well-being during the pandemic. Stricter restrictions on the municipality level were related only to a greater reduction in smoking and were not related to the other ten outcomes assessed in this study.

The results reveal that peer and parental relationships did not change substantially during the pandemic. These results thus suggest that the pandemic did not have alarming negative effects on overall satisfaction with social relationships, in contrast to concerns that peer relations and relationships within the family may suffer as an effect of the pandemic8,25. However, only one item each was used to assess peer and parental relationships, and future research is needed to provide more detailed information about how specific aspects of social interactions and close relationships have changed during the pandemic.

In the domain of mental health, the present study suggests that the pandemic may have had a negative effect on depressive symptoms. The results may be explained by the adverse effects of social isolation, the economic recession and disruptions in mental health care services due to the pandemic1,2. The results are in line with research showing substantial increases in mental health problems among adults early in the pandemic10,11,12,13. However, the increase of about 2.13 units on a scale from 0 to 100 and the small standardized effect size indicate that the change is considerably smaller than what has been found in studies on adults. The small increases are in accordance with findings from longitudinal studies on adolescents from the beginning of the pandemic that observed rather small changes in mental health problems3,14. Interestingly, contrary to expectations, we found no adverse changes during the pandemic in adolescents’ loneliness. This is possibly because adolescents’ relationships with peers and parents did not deteriorate during the pandemic. This finding is also in line with a longitudinal study among Norwegian adults that observed stable or even falling loneliness trends during the pandemic30.

In line with findings from a large-scale study in Iceland15, our results indicate that the pandemic may have affected substance use in a positive way, as adolescent alcohol intoxication and cannabis use declined during the pandemic. Physical distancing measures probably forced adolescents to stay at home under parental supervision more frequently and reduced the frequency of occasions when adolescents would have used drugs. The findings therefore differ from the results of a Canadian study indicating increased alcohol and cannabis use16. The retrospective assessment of substance use before the pandemic and the use of a convenience sample may be methodological explanations of the different results, in addition to the difference in national setting.

Physical activity did not change statistically significantly during the pandemic, whereas screen time increased. It may seem surprising that physical activity did not decrease, because adolescents’ opportunities to participate in organized sports activities were severely restricted during the pandemic. However, in line with research among German children and adolescents5, decreasing organized sports activities may have been counterbalanced by a substantial increase in recreational physical activities. This notion is also supported by evidence from Norway showing that recreational use of urban green space increased substantially during the pandemic31. Increased screen time outside school is in accordance with other studies measuring the effect of the pandemic on adolescents5,19 and may be explained by more leisure time spent online and more frequent use of digital media to socialize in times of restricted opportunities for organized leisure time activities and physical distancing measures.

Finally, we show that adolescents had less optimistic future life expectations during the pandemic than before. We suggest that the pandemic may have challenged adolescents’ feelings concerning physical safety and future economic security, which in turn may have increased worries about the future and decreased optimism.

In sum, the findings suggest negative changes in adolescents’ mental health and expectations about their future but also indicate decreased substance use during the pandemic. Of note, the observed effect sizes were small, with typical increases and decreases of a few percentage points.

Adolescents with low parental education and those from poor families showed more negative changes in several domains, including peer and parental relationships, mental health and physical activity. Poverty was additionally related to a smaller decrease in smoking, cannabis use and conduct problems. Other studies have demonstrated that people of lower socio-economic status are economically more severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic22,23. Our findings suggest that adolescents with low socio-economic backgrounds may be more affected by the pandemic not only economically but also in a variety of psychosocial domains. The results clearly indicate the need for societal means and measures to reduce the negative impact of the pandemic on underprivileged groups.

Moreover, the results suggest that sociodemographic factors such as gender and age may be additional sources of disparities in how the pandemic has affected adolescents’ lives. The disproportional adverse changes in mental health for girls during the pandemic are in line with the notion that adolescent girls are more reactive and more likely to become depressed as a consequence of substantial stress exposure than boys32. Our results are also in line with three studies demonstrating widening gender disparities in mental health during the pandemic in adolescents and adults4,10,15. We extend the literature by suggesting that the pandemic may affect girls more severely than boys in other psychosocial domains as well. Such gender differences include satisfaction with both peer and parental relationships, where post hoc analyses showed that these social relationships deteriorated statistically significantly during the pandemic among girls only.

This study finds that younger adolescents show more adverse changes during the pandemic than older adolescents. These differences were supported by post hoc analyses identifying statistically significant adverse changes during the pandemic for most psychosocial variables for the youngest adolescents (age 13), whereas few such negative changes were found for the oldest adolescents (age 18). Our results contrast with data from Iceland showing larger increases in depressive symptoms and larger decreases in cigarette smoking and alcohol intoxication during the pandemic among older than younger adolescents15. The conflicting results may be due to differences in national restrictions concerning schools, as older adolescents in Iceland may have experienced higher levels of restrictions15, whereas restrictions in junior and senior high schools in Norway did not differ substantially. Future research in other countries is needed to provide a better understanding of age-related changes during the pandemic.

The results suggest no association of municipality-level variations with infection rates. Also, stricter restrictions on the municipality level were related only to a greater reduction in smoking and not to any other outcome assessed in the study. We believe that such changes were largely not observed because infection rates varied only moderately in Norway. Moreover, by far the most restriction measures in Norway were implemented on the national level, and local variations may therefore have been of minor importance for adolescents’ psychosocial well-being. An important future focus of research may be to examine the effects of infection rates and restriction measures when comparing areas with larger variations in these figures, such as examining cross-country differences.

Our results need to be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, even though our analyses provide sound knowledge about changes in a variety of psychosocial variables about one year after the onset of the pandemic while accounting for general time trends, the study does not provide evidence of causal effects of the pandemic. We acknowledge that deviations from the general trend during the pandemic in 2021 may partly be caused by societal changes in this year that are unrelated to the COVID-19 pandemic. Future studies that isolate the causal effects of the pandemic are therefore needed.

Second, concerning measurement, we assessed some of the variables with one item only. We also acknowledge that some of these measures (for example, peer and parental relationships and future life expectations) have not been previously validated. In addition, even though we asked about screen time outside of school, the increase in screen time during the pandemic may be partly explained by the increased use of digital devices for schooling purposes during the pandemic. Future studies should therefore include more comprehensive measures with known psychometric properties. We operationalized family poverty using an item on perceived family economic situation, but a more objective measure of family income would have been preferable. Moreover, the study did not conduct more extensive assessments of disadvantage, such as ethnic minority status or gender identity and sexual orientation. Also, we did not directly assess age but assessed it only on the basis of school grade. However, previous Norwegian studies have found nearly perfect correlations between age and school grade33.

Third, compared with other years of data collection, response rates were considerably lower in 2020. This is because some school classes could not participate, as they were scheduled to respond to the survey when schools were already closed due to the lockdown. However, the risk of bias due to the lower response rate in 2020 is low, because non-participation was primarily due to random factors such as when the survey was planned to be conducted.

Fourth, the study provides only annual assessments of the outcomes examined. More frequent assessments would have uncovered more fine-grained temporal patterns of change during and before the pandemic.

Finally, our results are specific to Norway and do not generalize beyond the specific national context and underlying target population. Of note, Norway has had fewer COVID-19-related deaths and lower infection rates than many other countries.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that during the pandemic, Norwegian adolescents’ depressive symptoms and time spent in front of screens increased, whereas optimistic future life expectations, alcohol intoxication and cannabis use decreased. The effects were of small size and may not in themselves point to alarming adverse effects of the pandemic. However, of concern is the consistent finding that girls, young adolescents and adolescents with lower socio-economic backgrounds show more adverse changes during the pandemic. This finding suggests that the pandemic, in line with other crises, may disproportionally affect the disadvantaged. And similar to other crises, the disproportionally negative effects may be long-lasting and negatively affect the disadvantaged far beyond the duration of the pandemic20. To mitigate this, we suggest developing and implementing measures in Norway such as economic support and public health interventions that are aimed at buffering adverse changes during the pandemic for adolescents and their families with low socio-economic resources. Moreover, the particular vulnerability of girls and the youngest adolescents have to be taken into account when developing interventions in Norway. Norway is a typical social democratic welfare state34, characterized by rather extensive social welfare services and benefits, including a universal health insurance system, which differs substantially from health care systems in countries such as the United Kingdom or the United States. It remains to be seen how our findings regarding changes during the pandemic and increasing disparities in Norway compare to those in other countries. Examining psychosocial outcomes and social disparities during the pandemic in other countries will be an important research focus in the future.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Department of Psychology internal research ethics committee at the University of Oslo (reference no. 13710027) and complies with all ethical regulations.

Data and participants

The present study used data from Norwegian nationwide Ungdata surveys. Ungdata is a national data collection scheme designed to conduct youth surveys at the national and municipal levels in Norway. It is regarded as the most wide-ranging source of data on adolescent health and well-being in Norway, and adolescents in almost all municipalities are regularly assessed, typically every third year. The Ungdata data collection scheme was started in 2010 but has been fully implemented for all junior and senior high school students (grades 8 to 13, students aged 13 to 18) since 2014. Participating students were invited to complete an electronic questionnaire in class, covering various aspects of young people’s lives, including social relationships, mental health, substance use, health behaviour, norm-breaking behaviour, exposure to negative life events and leisure activities.

Data collection was conducted each spring. In 2020, data collection started in January but was discontinued when schools were closed in Norway on 12 March. At that time, only some of the participating municipalities had finished considerable parts of the data collection. In 2021, 204 municipalities participated in Ungdata from January to the end of March. The data from four municipalities were not used, because no Ungdata surveys had been conducted before 2021 in these municipalities. Moreover, in 43 small municipalities, one or several of the outcomes, predictors or controls were not assessed, because the limited number of adolescents living in these municipalities required Ungdata to omit items from the questionnaires to ensure the anonymity of all participants. The data from these municipalities were excluded as well. In all but one of the excluded municipalities, fewer than 100 adolescents participated in 2021, and few participants attended senior high school, because senior high schools were typically not situated in small municipalities such as those excluded from the study. When comparing adolescents in the excluded municipalities with those in the included municipalities, we observed no statistically significant differences in satisfaction with parental relationships, loneliness, physical activity and future life expectations (P > 0.05). However, the excluded participants scored lower on satisfaction with peer relations, depressive symptoms, screen time and all forms of substance use (P < 0.01). These differences in age-sensitive psychosocial variables were probably due to potential age differences between the excluded and included participants; however, because age (or school grade) was one of the variables that was typically not assessed in the excluded municipalities due to anonymity considerations, it was not possible to control for age when comparing the excluded and included adolescents. Of the remaining 157 municipalities included in the study, 43, 70, 41 and 3 municipalities had conducted one, two, three and four data collections before 2021, respectively. We included all data available from 2014 to 2021 from these 157 municipalities in the present study. As a result, we used data from N = 227,258 adolescents who had participated in Ungdata in 2021 and at least at one previous data collection. Due to the inclusion criteria, the number of municipalities participating in each year before 2021 was considerably smaller than that in 2021 (Table 1). Because the data were already collected, no statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample size. However, our sample size was larger than those reported in previous publications15. All participants and their parents were informed that participation in Ungdata is voluntary. Parents had the ability to withdraw their children from participation.

Measures

Social relationships

Peer relationships were assessed by one item asking how satisfied the respondents were with their friendships with peers. Parental relationships were assessed in a similar way by asking how satisfied the respondents were with their parents. Both items were measured by a five-point scale ranging from ‘very unsatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’. Both items were modelled after instruments measuring domain-specific subjective well-being by assessing satisfaction with particular aspects of life, such as the Personal Wellbeing Index35. Items about satisfaction with specific domains of life are considered meaningful as stand-alone measures and are considered particularly useful when seeking specific effects of policy interventions36.

Mental health

Depressive symptoms were measured by Kandel and Davies’s six-item Depressive Mood Inventory37. This measure was derived from the widely used Hopkins Symptom Checklist38 and assesses depressive symptoms during the preceding week on a four-point scale from ‘affected not at all’ to ‘affected extremely’. In the present study, internal consistency was α = 0.89, and the scale has been shown to correlate highly with other measures of adolescent depressive symptoms in Norway39. Loneliness was assessed by one item on feelings of loneliness in the past week, with the same response options. Single items that ask directly about feelings of being lonely are widely used to assess loneliness and have been shown to have good face validity and predictive utility40.

Substance use and conduct problems

Adolescents’ smoking behaviour was assessed, which we categorized into those who did not smoke (1), those who smoked less than once a week (2), those who smoked every week but not daily (3) and daily smokers (4). Alcohol intoxication was assessed by asking how often over the past year participants had consumed so much alcohol that they clearly felt intoxicated. We also assessed cannabis use in the past year. Previous studies have supported the reliability of self-reports of substance use and indicate that close-ended questions like those used in our study provide more reliable estimates of substance use than open-ended questions41,42. Conduct problems were assessed by five items on the frequency of stealing, vandalism, truancy, staying away from home without parents knowing about the respondent’s whereabouts and not paying at public transportation or events. The items were based on selected questions from standard instruments to assess antisocial behaviour, such as Olweus’s scale of antisocial behaviour43 and the National Youth Longitudinal Study44. A composite score of the five items was computed, and internal consistency was α = 0.61. The response options for alcohol intoxication, cannabis use and conduct problems items were on a five-point scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘more than 10 times’.

Physical activity and screen time

The respondents’ physical activity was assessed by the item ‘How often do you engage in physical activity that makes you breathe hard or sweat?’, on a scale ranging from 1 (‘never’) to 6 (‘at least five times a week’). It has been argued that a one-item measure of this kind is probably more reliable than more complex and comprehensive measures of physical activity in young people45. A unique challenge when assessing screen time is the quickly changing media and technology landscape, which poses a challenge to valid assessment of adolescent media use across time. Multi-item instruments that assess the use of specific screen-based devices or behaviours can be problematic, as such instruments may already be outdated within a few years46. Because our study spanned a period of considerable changes in adolescent digital technology use and screen behaviour, we chose a different strategy and assessed screen time by one item asking the respondents about their overall daily screen time outside of school with response options ranging from 1 (‘no time’) to 6 (‘more than 3 hours’).

Future life expectations

Future life expectations were assessed by one item about whether the respondents expected to live a good and happy life. The response options were ‘yes’, ‘no’, and ‘don’t know’. We contrasted those who responded that they expected to live a good and happy life (yes) with all other adolescents (no and don’t know). Similar single-item measures in the domain of anticipated future life satisfaction have been used frequently and have shown to have adequate rank-order stability in longitudinal studies47,48.

Indicators of socio-economic status and other demographics

Low parental education was operationalized by whether at least one of the parents had a university or college education or not. Perceived family poverty was measured by asking ‘Has your family’s economic situation been good or bad during the past two years?’, with five response options ranging from ‘always good’ to ‘always bad’. We contrasted those who perceived their family’s economic situation as ‘mostly bad’ or ‘always bad’ with all other adolescents. Gender was assessed. For anonymity concerns, only school grade (grades 8 to 13) but not age was assessed. In the Norwegian school system, attendance in school grades is strictly organized by birth cohorts, and staying back (repeating a grade) due to poor academic performance is generally not practised. We therefore used school grade as an indicator of age, where grade 8 corresponds to age 13 and grade 13 corresponds to age 18.

Municipality-level variables

Municipality-level data on total COVID-19 infection rates per 100,000 residents from the onset of the pandemic to 31 March 2021 were obtained from the Norwegian Surveillance System for Communicable Diseases. Because restrictions to control the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic varied across municipalities, we used a database of all restrictions on the municipality level that is operated by one of the largest national newspapers in Norway, Verdens Gang. The database is continuously updated by direct contact with the municipalities and by monitoring municipality webpages, official documents and official announcements. We identified all registered restrictions that were directed towards junior and senior high schools in the municipalities, as they were the only restrictions that were specifically directed towards adolescents, and we calculated the number of weeks with stricter restrictions in municipalities than what had been imposed by national authorities. These restrictions included local school closures and other local restrictions at schools to reduce infection rates. Municipalities without such registered local restrictions during the pandemic (that is, 12 March 2020 to 31 March 2021) were coded with 0 weeks of restrictions, and municipalities that had imposed restrictions at any time during the pandemic were coded with the number of weeks they had had local restrictions.

Analyses

We transformed all dependent variables into POMP scores28. Thus, in line with the POMP score approach, the variables were rescaled with minimum and maximum possible scores of 0 and 100. The scores can be interpreted as the percentage of the maximum possible score achievable on the scale28.

Due to the hierarchical structure of the data, with individuals nested within municipalities observed repeatedly over time, we used multilevel regression models in all analyses. At the higher level, we used municipality and not school, because information about students’ school affiliation was not available due to anonymity considerations. We applied the societal growth curve approach to multilevel modelling, as introduced by Fairbrother6. This approach was specifically developed for designs such as Ungdata, where multiple geographical units (such as municipalities) are observed across time, but at each point of observation, a different representative cross-sectional sample of individuals is drawn from the population49,50. The method thus allows assessment of how aggregated individual characteristics develop over time within repeatedly sampled higher-level units (that is, municipalities). More specifically, using multilevel linear regression analyses, we constructed growth curves for each municipality to model time trends on the municipality level from 2014 to 2021 for indicators of psychosocial well-being. All models were estimated as random-intercept multilevel linear regressions with individuals at the lowest level, clustered within municipality years at the middle level and municipalities at the highest level. The inclusion of random intercepts at the municipality-years level and municipality level was also supported empirically, since variability in the random intercepts at the higher levels was found to be statistically significantly different from zero for all outcomes (P < 0.05).

The overall pattern of change over time was modelled as a curvilinear trend, through the inclusion of both linear and quadratic terms for the number of years that had passed since the first included survey wave in 2014. We also measured the effect of the pandemic in 2021 above the curvilinear development by including a dummy variable for the 2021 wave (coded 1 for participation in the 2021 data wave and 0 for participation in all other data waves; for another application of this approach, see ref. 49). Due to convergence issues, the societal growth curve slope parameters and the pandemic effects were fixed to be the same across all municipalities. More specifically, the societal growth model was specified by means of the following equation:

with

where Yitj represents a psychosocial characteristic for adolescent i at data collection wave t in municipality j. β0 represents the grand intercept across all municipalities, and β1 and β2 represent the linear slope and quadratic slope of the societal growth curve, respectively. β3 is the coefficient for the dummy, indicating the deviation of the dependent variable in the pandemic year of 2021 above the general trend as expressed by the growth curve. Moreover, the model includes random intercepts for the municipality (v0j) and municipality-year level (u0tj). The two, together with the individual-level error term (eitj), are assumed to be distributed normally, with a mean of 0.

Because all dependent variables were recoded into POMP scores, the pandemic effect can be interpreted in terms of percentage-point change of the percentage of the maximum possible score achievable on the scale28. We controlled for parental education, gender and age (not shown in the equation) to adjust for individual-level compositional differences that may have affected the societal growth curves or the estimated effect of the pandemic51.

To examine whether the pandemic disproportionally affected particular groups of adolescents, we included interaction terms of the pandemic effect variable (the dummy variable for the 2021 wave) with the individual-level predictors of parental educational background, perceived family poverty, gender and age. By including such interaction terms in our models, we examined whether changes in outcomes during the pandemic above general time trends (that is, the estimated effect of the pandemic) differed across sociodemographic groups. We then calculated point estimates of these conditional effects for specific values of the moderator variables52. We also explored whether the estimated effect of the pandemic varied with municipality infection rates and extent of imposed restrictions. For this purpose, we included cross-level interactions of the pandemic effect with infection rates and extent of restriction measures. Also in the interaction analyses, parental education, gender and age were included as covariates.

In line with best practices for multilevel modelling53, all predictors and controls were grand-mean centred to facilitate the interpretation of the estimates. The amount of missing data for all study variables ranged from 2% for conduct problems to 10% for parental education. Even though the methodological literature on handling missing data in multilevel modelling has been rapidly developing in recent years, modern missing data techniques such as multiple imputation have not yet been developed sufficiently for complex three-level models with interactions54. We therefore applied listwise deletion to deal with item non-response. Distributional assumptions are difficult to test in complex multilevel models55; data distribution was therefore assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. Simulation studies have shown that the effect of violations of distributional assumptions is small and results in little bias even with substantially skewed distributions55. We used R version 4.0.3 for all analyses. All multilevel regressions were conducted using the lme4 package for R (version 1.1.26)56. The interplot package for R (version 0.2.3)57 was used to estimate conditional effects for the interaction analyses. All P values were based on two-tailed hypothesis tests.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Norwegian Social Research (NOVA), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study and so are not publicly available. The data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of Norwegian Social Research (NOVA).

Code availability

The code for all analyses reported in the manuscript is available on request.

References

Golberstein, E., Wen, H. & Miller, B. F. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 174, 819–820 (2020).

Holmes, E. A. et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatr. 7, 547–560 (2020).

Hafstad, G. S., Sætren, S. S., Wentzel-Larsen, T. & Augusti, E.-M. Adolescents’ symptoms of anxiety and depression before and during the COVID-19 outbreak: a prospective population-based study of teenagers in Norway. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 5, 100093 (2021).

Magson, N. R. et al. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 50, 44–57 (2021).

Schmidt, S. C. E. et al. Physical activity and screen time of children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 lockdown in Germany: a natural experiment. Sci. Rep. 10, 21780 (2020).

Fairbrother, M. Two multilevel modeling techniques for analyzing comparative longitudinal survey datasets. Polit. Sci. Res. Meth. 2, 119–140 (2014).

Orben, A., Tomova, L. & Blakemore, S.-J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 4, 634–640 (2020).

Prime, H., Wade, M. & Browne, D. T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 75, 631–643 (2020).

Bruining, H., Bartels, M., Polderman, T. J. C. & Popma, A. COVID-19 and child and adolescent psychiatry: an unexpected blessing for part of our population? Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. 30, 1139–1140 (2021).

Pierce, M. et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatr. 7, 883–892 (2020).

Twenge, J. M. & Joiner, T. E. Mental distress among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Psychol. 76, 2170–2182 (2020).

McGinty, E. E., Presskreischer, R., Han, H. & Barry, C. L. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA 324, 93–94 (2020).

Ebrahimi, O. V., Hoffart, A. & Johnson, S. U. Physical distancing and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: factors associated with psychological symptoms and adherence to pandemic mitigation strategies. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 9, 489–506 (2021).

Barendse, M. E. A. et al. Longitudinal change in adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international collaborative of 12 samples. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/hn7us (2021).

Thorisdottir, I. E. et al. Depressive symptoms, mental wellbeing, and substance use among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iceland: a longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Psychiatr. 8, 663–672 (2021).

Dumas, T. M., Ellis, W. & Litt, D. M. What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID-19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic-related predictors. J. Adolesc. Health 67, 354–361 (2020).

Boman, J. H. & Gallupe, O. Has COVID-19 changed crime? Crime rates in the United States during the pandemic. Am. J. Crim. Justice 45, 537–545 (2020).

Hall, G., Laddu, D. R., Phillips, S. A., Lavie, C. J. & Arena, R. A tale of two pandemics: how will COVID-19 and global trends in physical inactivity and sedentary behavior affect one another? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 64, 108–110 (2021).

Xiang, M., Zhang, Z. & Kuwahara, K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents’ lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 63, 531–532 (2020).

Arthi, V. & Parman, J. Disease, downturns, and wellbeing: economic history and the long-run impacts of COVID-19. Explor. Econ. Hist. 79, 101381 (2021).

Heggebø, K., Tøge, A. G., Dahl, E. & Berg, J. E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health during the Great Recession: a scoping review of the research literature. Scand. J. Public Health 47, 635–654 (2018).

Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M. & Rauh, C. Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: evidence from real time surveys. J. Public Econ. 189, 104245 (2020).

Perry, B. L., Aronson, B. & Pescosolido, B. A. Pandemic precarity: COVID-19 is exposing and exacerbating inequalities in the American heartland. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2020685118 (2021).

Benner, A. D. & Mistry, R. S. Child development during the COVID-19 pandemic through a life course theory lens. Child Dev. Perspect. 14, 236–243 (2020).

Cluver, L. et al. Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet 395, e64 (2020).

Crick, N. R. & Zahn-Waxler, C. The development of psychopathology in females and males: current progress and future challenges. Dev. Psychopathol. 15, 719–742 (2003).

WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard https://covid19.who.int/ (World Health Organization, 2021).

Cohen, P., Cohen, J., Aiken, L. S. & West, S. G. The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivar. Behav. Res. 34, 315–346 (1999).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences 2nd edn (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988).

Hansen, T. et al. Locked and lonely? A longitudinal assessment of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Scand. J. Public Health 49, 766–773 (2021).

Venter, Z. S., Barton, D. N., Gundersen, V., Figari, H. & Nowell, M. Urban nature in a time of crisis: recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104075 (2020).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: the role of gender. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 8, 161–187 (2012).

Aarø, L. E. et al. Mental and somatic complaints among adolescents. J. Norweg. Med. Assoc. 121, 2923–2927 (2001).

Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (Princeton Univ. Press, 1990).

Cummins, R. A., Eckersley, R., Pallant, J., van Vugt, J. & Misajon, R. Developing a national index of subjective wellbeing: the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index. Soc. Indic. Res. 64, 159–190 (2003).

OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being (OECD, 2013).

Kandel, D. B. & Davies, M. Epidemiology of depressive mood in adolescents. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 39, 1205–1212 (1982).

Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H. & Covi, L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav. Sci. 19, 1–15 (1974).

von Soest, T. & Wichstrøm, L. Secular trends in depressive symptoms among Norwegian adolescents from 1992 to 2010. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 42, 403–415 (2014).

Nicolaisen, M. & Thorsen, K. Impairments, mastery, and loneliness: a prospective study of loneliness among older adults. Norweg. J. Epidemiol. 22, 143–150 (2012).

Johnson, T. P. & VanGeest, J. B. in Research Methods in the Study of Substance Abuse (eds VanGeest, J. B. et al.) 251–283 (Springer, 2017).

Barnea, Z., Rahav, G. & Teichman, M. The reliability and consistence of self-reports on substance use in a longitudinal study. Br. J. Addict. 82, 891–898 (1987).

Olweus, D. in Crossnational Research in Self-Reported Crime and Delinquency (ed. Klein, M. W.) 187–201 (Kluwer, 1989).

Windle, M. A longitudinal study of antisocial behaviors in early adolescence as predictors of late adolescent substance use—gender and ethnic group differences. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 99, 86–91 (1990).

Brodersen, N. H., Steptoe, A., Williamson, S. & Wardle, J. Sociodemographic, developmental, environmental, and psychological correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior at age 11 to 12. Ann. Behav. Med. 29, 2–11 (2005).

Gunnell, K. E., Brunet, J. & Bélanger, M. Out with the old, in with the new: assessing change in screen time when measurement changes over time. Prev. Med. Rep. 9, 37–41 (2018).

DeGagne, B. & Busseri, M. A. The impact of better- versus worse-than-average comparisons on beliefs about how life satisfaction is unfolding over time, affect, and motivation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 51, 610–626 (2021).

Lang, F. R., Weiss, D., Gerstorf, D. & Wagner, G. G. Forecasting life satisfaction across adulthood: benefits of seeing a dark future? Psychol. Aging 28, 249–261 (2013).

Meuleman, B., Davidov, E. & Billiet, J. Modeling multiple-country repeated cross-sections: a societal growth curve model for studying the effect of the economic crisis on perceived ethnic threat. Meth. Data Anal. 12, 185–210 (2018).

Schmidt-Catran, A. W. & Fairbrother, M. The random effects in multilevel models: getting them wrong and getting them right. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 32, 23–38 (2016).

Snijders, T. & Bosker, R. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling 2nd edn (Sage, 2012).

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R. & Golder, M. Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Polit. Anal. 14, 63–82 (2006).

Enders, C. K. & Tofighi, D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychol. Meth. 12, 121–138 (2007).

van Buuren, S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data (Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2018).

Schielzeth, H. et al. Robustness of linear mixed-effects models to violations of distributional assumptions. Meth. Ecol. Evol. 11, 1141–1152 (2020).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1 (2015).

Solt, F. & Hu, Y. Interplot: Plot the effects of variables in interaction terms. R package version 0.2.3 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/interplot/vignettes/interplot-vignette.html (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by three grants from the Research Council of Norway: grant nos 288083 (T.v.S. and V.S.U.), 300816 (T.v.S., M.K., R.R.-C. and E.F.H.) and 301010 (T.v.S., M.K., S.F. and L.C.-G.). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.v.S. conceptualized the study and drafted the manuscript. M.K. conducted all statistical analyses and contributed to conceptualizing the study and writing the manuscript. R.R.-C., S.F. and L.C.-G. contributed to conceptualizing the study and writing the manuscript. V.S.U. acquired and prepared the municipality-level data on COVID-19 infection rates and COVID-19-related restrictions. E.F.H. created the figures and contributed to writing the manuscript. A.B. was in charge of the data collection in Ungdata and contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Bryndís Björk Ásgeirsdóttir, Peter de Jonge and Natasha Magson for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

von Soest, T., Kozák, M., Rodríguez-Cano, R. et al. Adolescents’ psychosocial well-being one year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nat Hum Behav 6, 217–228 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01255-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01255-w

This article is cited by

-

Residential mobility restrictions and adverse mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Secular trends in mental health problems among young people in Norway: a review and meta-analysis

European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2024)

-

Locked Down: The Gendered Impact of Social Support on Children’s Well-Being Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Child Indicators Research (2024)

-

School learning modes during the COVID-19 response and pre- to during pandemic mental health changes in a prospective cohort of Canadian adolescents

Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (2024)

-

COVID-19 pandemic impact on adolescent mental health: a reassessment accounting for development

European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2024)