The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and resulting viral syndrome (COVID-19) was first reported in China during December 2019 and within weeks emerged in the US.1 Since it is a rapidly evolving situation, clinicians must remain current on best practices—a challenging institutional responsibility. According to LitCovid, a curated literature hub for tracking scientific information on COVID-19, there are > 54,000 articles on the subject in PubMed. Among these include venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis guidance from 4 respected thrombosis organizations/societies and the US National Institutes of Health.1-5

Observations

COVID-19 predisposes patients with and without a history of cardiovascular disease to thrombotic complications, occurring in either the venous or arterial circulation system.2,6 Early observational studies suggest that thrombotic rates may be in excess of 20 to 30%; however, the use of prophylactic anticoagulation was inconsistent among studies that were rushed to publication.6

Autopsy data have demonstrated the presence of fibrin thrombi within distended small vessels and capillaries and extensive extracellular fibrin deposition.6 Investigators compared the characteristics of acute pulmonary embolism in 23 cases with COVID-19 but with no clinical signs of deep vein thrombosis with 100 controls without COVID-19.7 They observed that thrombotic lesions had a greater distribution in peripheral lung segments (ie, peripheral arteries) and were less extensive for those with COVID-19 vs without COVID-19 infection. Thus, experts currently hypothesize that COVID-19 has a distinct “pathomechanism.” As a unique phenotype, thrombotic events represent a combination of thromboembolic disease influenced by components of the Virchow triad (eg, acute illness and immobility) and in situ immunothrombosis, a local inflammatory response.6,7

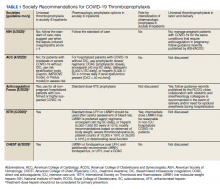

Well-established surgical and nonsurgical VTE thromboprophylaxis guidelines serve as the foundation for current COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis guidance.8,9 Condition specific guidance is extrapolated from small, retrospective observational studies or based on expert opinion, representing levels 2 and 3 evidence, respectively.1-5 Table 1 captures similarities and differences among COVID-19 VTE thromboprophylaxis recommendations which vary by time to publication and by society member expertise gained from practice in the field.

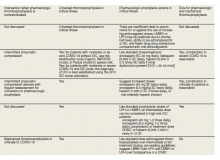

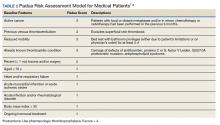

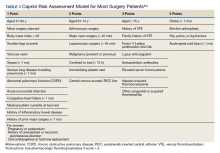

Three thrombosis societies recommend universal pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for acutely ill COVID-19 patients who lack contraindications.3-5 Others recommend use of risk stratification scoring tools, such as the Padua risk assessment model (RAM) for medical patients or Caprini RAM for surgical patients, the disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) score, or the sepsis-induced coagulopathy score to determine therapeutic appropriateness (Tables 2 and 3).1,2 Since most patients hospitalized for COVID-19 will present with a pathognomonic pneumonia and an oxygen requirement, they will generally achieve a score of ≥ 4 when the Padua RAM is applied; thus, representing a clear indication for pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.8,9 If the patient is pregnant, the Anticoagulation Forum recommends pharmacologic prophylaxis, consultation with an obstetrician, and use of obstetrical thromboprophylaxis guidelines.3,10,11

Most thrombosis experts prefer parenteral thromboprophylaxis, specifically low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or fondaparinux, for inpatients over use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in order to minimize the potential for drug interactions particularly when investigational antivirals are in use.4 Once-daily agents (eg, rivaroxaban, fondaparinux, and enoxaparin) are preferred over multiple daily doses to minimize staff contact with patients infected with COVID-19.4,5 Fondaparinux and DOACs should preferentially be used in patients with a recent history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with and without thrombosis (HIT/HITTS). Subcutaneous heparin is reserved for patients who are scheduled for invasive procedures or have reduced renal function (eg, creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min).1,3-5 In line with existing pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis guidance, standard prophylactic LMWH doses are recommended unless patients are obese (body mass index [BMI] > 30) or morbidly obese (BMI > 40) necessitating selection of intermediate doses.4

Since early non-US studies demonstrated high thrombotic risk without signaling a potential for harm from pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, some organizations recommend empiric escalation of anticoagulation doses for critical illness.3,4,6 Thus, it may be reasonable to advance to either intermediate pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis dosing or therapeutic doses.3 However, observational studies question this aggressive practice unless a clear indication exists for intensification (ie, atrial fibrillation, known VTE).

A large multi-institutional registry study that included 400 subjects from 5 centers demonstrated a radiographically confirmed VTE rate of 4.8% and an arterial thrombosis rate of 2.8%.6 When limiting to the critically ill setting, VTE and arterial thrombosis occurred at slightly higher rates (7.6% and 5.6%, respectively). Patients also were at risk for nonvessel thrombotic complications (eg, CVVH circuit, central venous catheters, and arterial lines). Subsequently, the overall thrombotic complication rate was 9.5%. All thrombotic events except one arose in patients who were receiving standard doses of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. Unfortunately, D-dimer elevation at admission was not only predictive of thrombosis and death, but portended bleeding. The overall bleeding rate was 4.8%, with a major bleeding rate of 2.3%. In the context of observing thromboses at normally expected rates during critical illness in association with a significant bleeding risk, the authors recommended further investigation into the net clinical benefit.

Similarly, a National Institutes of Health funded, observational, single center US study evaluated 4,389 inpatients infected with COVID-19 and determined that therapeutic and prophylactic anticoagulation reduced inpatient mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.53 and 0.50, respectively for the primary outcome) and intubation (aHR, 0.69 and 0.72, respectively) over no anticoagulation.12 Notably, use of inpatient therapeutic anticoagulation commonly represented a continuation of preadmission therapy or progressive COVID-19. A subanalysis demonstrated that timely use (eg, within 48 hours of admission) of prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation, resulted in no difference (P < .08) in the primary outcome. Bleeding rates were low overall: 3%, 1.7%, and 1.9% for therapeutic, prophylactic, and no anticoagulation groups, respectively. Furthermore, selection of DOACs seems to be associated with lower bleeding rates when compared with that of LMWH heparin (1.3% vs 2.6%, respectively). In those where site of bleeding could be ascertained, the most common sites were the gastrointestinal tract (50.7%) followed by mucocutaneous (19.4%), bronchopulmonary (14.9%), and intracranial (6%). In summary, prophylactic thromboprophylaxis doses seem to be associated with positive net clinical benefit.

As of October 30, 2020, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) had reported 75,156 COVID-19 cases and 3,961 deaths.13 Since the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) does not disseminate nationally prepared anticoagulation order sets to the field, facility anticoagulation leads should be encouraged to develop local guidance-based policies to help standardize care and minimize further variations in practice, which would likely lack evidential support. Per the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS)- Nashville/Murfreesboro anticoagulation policy, we limit the ordering of parenteral anticoagulation to Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) order sets in order to provide decision support (eFigure 1, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0063). Other facilities have shown that embedded clinical decision support tools increase adherence to guideline VTE prophylaxis recommendations within the VA.14

In April 2020, the TVHS anticoagulation clinical pharmacy leads developed a COVID-19 specific order set based on review of societal guidance and the evolving, supportive literature summarized in this review with consideration of provider familiarity (eFigure 2, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0063)). Between April and June 2020, the COVID-19 order set content consistently evolved with publication of each COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis guideline.1-5

Since TVHS is a high-complexity facility, we elected to use universal pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19. This construct bypasses the use of scoring tools (eg, RAM), although we use Padua and Caprini RAMS for medical and surgical patients, respectively, who are not diagnosed with COVID-19. The order set displays all acceptable guideline recommended options, delineated by location of care (eg, medical ward vs intensive care unit), prior history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and renal function. Subsequently, all potential agents, doses, and dosing interval options are offered so that the provider autonomously determines how to individualize the clinical care. Since TVHS has only diagnosed 932 ambulatory/inpatient COVID-19 cases combined, our plans are to complete a future observational analysis to determine the effectiveness of the inpatient COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis order set for our internal customers.