Abstract

Background

Systemic rheumatic diseases are characterized by diverse symptoms that are exacerbated by stressors.

Questions/Purposes

Our goal was to identify COVID-19-related stressors that patients associated with worsening rheumatic disease symptoms.

Methods

With approval of their rheumatologists, patients at an academic medical center were interviewed with open-ended questions about the impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Responses were analyzed with qualitative methods using grounded theory and a comparative analytic approach to generate categories of stressors.

Results

Of 112 patients enrolled (mean age 50 years, 86% women, 34% non-white or Latino, 30% with lupus, 26% with rheumatoid arthritis), 2 patients had SARS-CoV-2 infection. Patients reported that coping with challenges due to the pandemic both directly and indirectly worsened their rheumatic disease symptoms. Categories associated with direct effects were increased fatigue (i.e., from multitasking, physical work, and taking precautions to avoid infection) and worsening musculoskeletal and cognitive function. Categories associated with indirect effects were psychological worry (i.e., about contracting SARS-COV-2, altering medications, impact on family, and impact on job and finances) and psychological stress (i.e., at work, at home, from non-routine family responsibilities, about uncertainty related to SARS-CoV-2, and from the media). Patients often reported several effects coalesced in causing more rheumatic disease symptoms.

Conclusion

Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with rheumatic disease–related physical and psychological effects, even among patients not infected with SARS-CoV-2. According to patients, these effects adversely impacted their rheumatic diseases. Clinicians will need to ascertain the long-term sequelae of these effects and determine what therapeutic and psychological interventions are indicated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Systemic rheumatic diseases are characterized by diverse symptoms that can be exacerbated by physical, psychological, environmental, and unknown stressors [4, 7, 18]. These symptoms can diminish function and quality of life, and influence the choice and dose of medications [11]. In addition to serious adverse events in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the pandemic has caused population-wide upheaval in terms of physical, psychosocial, and economic well-being [5, 14]. Sustaining routine daily life and pursuing existing goals have become priorities that require extra physical and mental effort which may exacerbate symptoms commonly seen in rheumatic diseases [5]. Understanding these effects may help patients and clinicians interpret new or worsening symptoms and alert them to potential adverse disease sequelae.

During the height of the pandemic in New York City, we conducted a qualitative study to learn about rheumatic disease patients’ experiences with COVID-19 and the challenges they faced in coping with the pandemic. The topic of inquiry of this report was whether the extra physical and mental effort required to cope with the pandemic contributed to exacerbation of rheumatic disease symptoms.

Methods

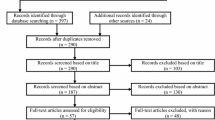

This study was approved by the IRB at our institution, and all patients provided verbal consent. Enrollment occurred from April 2, 2020, through April 21, 2020, which coincided with the height of the pandemic in New York City (Fig. 1). Patients with a recent clinical encounter or email correspondence with their physician were referred to this study by their rheumatologists or were identified from recent telehealth visits and were approved to be recruited by their rheumatologist. Thirteen rheumatologists participated in this study and were chosen because of the breadth of their patients’ diagnoses and sociodemographic characteristics and their willingness to participate in clinical research.

Patients were eligible if they had a rheumatologist-diagnosed inflammatory rheumatic disease, spoke English, and were taking at least one disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug. All patients were interviewed by telephone by two investigators, who participated on each call. Both investigators are non-rheumatologists and have experience collecting and analyzing qualitative data. Patients were asked about the impact of COVID-19 with the following open-ended questions: “Overall, how has COVID-19 affected your life (potential probes: job, social interactions, psychological well-being, roles)?” “What have you done to protect yourself from COVID-19?” Both investigators wrote down patients’ responses in field notes. Responses were summarized and read back to patients as a means of response validation [3, 6, 9]. After each interview the investigators conferred to create a single composite account of the interview, which was then transcribed into individual narratives.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained from electronic medical records, including laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis.

The analysis was conducted according to grounded theory and an inductive and interpretive framework [3, 6, 7, 12, 15]. Using open-coding, responses were reviewed line-by-line to generate concepts [9, 12]. Concepts were then grouped into categories through a repeated process according to the topics they represented [1, 12, 17]. Categories were then refined based on a comparative analytic strategy to ensure they encompassed distinct features [12]. Categories were then clustered under overarching themes, which were named according to the phenomena they represented. Data saturation, the point when no new concepts were volunteered during the interviews, was attained [10]. Two other investigators with expertise in rheumatology and qualitative analysis independently reviewed the narratives and affirmed (i.e., corroborated) that they agreed with the categories and themes [2, 12].

Results

In total, 112 patients were enrolled; 105 were interviewed at the time of the initial telephone contact and 7 were interviewed at a preferred time several days later. An additional 2 patients agreed to participate but could not be interviewed before the study closed, and 3 refused due to inconvenient timing and reluctance to discuss personal circumstances.

The mean age was 50 years, 86% were women, and 34% were self-described as non-white race or Latino ethnicity (Table 1). Patients had a spectrum of rheumatic disease diagnoses and prescribed medications. Two patients had laboratory-confirmed diagnoses of SARS-CoV-2 infection; one was hospitalized and the other was treated as an outpatient.

To the open-ended questions, patients answered that coping with challenges due to the pandemic directly and indirectly worsened their rheumatic disease symptoms. Themes associated with direct effects were increased fatigue and limitations in musculoskeletal and cognitive function, and themes associated with indirect effects were increased psychological worry and stress. Another theme linked patients’ perspectives on how these effects adversely impacted their rheumatic disease.

Fatigue was a common complaint. A major source of increased fatigue was multitasking and balancing personal and work responsibilities while sheltering-in-place at home (Table 2). Expanded family responsibilities included continuously caring for children and senior parents, overseeing school work, managing more household chores, and assisting extended family members by assuming these roles for them. Households often increased in number as families pooled their resources for mutual aid and to protect their more vulnerable members from community exposure to the virus. At the same time, while working from home was a welcomed alternative, it required establishing new routines, accommodating several work-at-home family members, and integrating teleconferencing into home life.

“I work more hours now from home than at the job. I also have my mother at home to take care of.”

“I don’t have a nanny now so I have more child care. It’s very challenging with work. I am multitasking and very fatigued with all these roles.”

Some patients had increased fatigue from fulfilling new responsibilities that required markedly more physical work and exertion (Table 2). These included work-related tasks, caring for sick family members, and performing household chores that otherwise would have been performed with assistance.

“We own a horse farm. It is so physically taxing, I am so tired. I have to do more than usual because we do not have help coming in. I fall asleep as soon as I get in the house and sleep for hours. But the sleep doesn’t make me unfatigued.”

“Our son got very sick in March; we think it was the virus because all of his room-mates were sick too. He came home from college and I took care of him. He had high fevers and sweating; I had to changes his sheets five nights in a row. It was so intense. I am having a lot of symptoms and a flare up now.”

Patients also reported fatigue from implementing precautions to decrease their risk of infection (Table 2). These included routine precautions, such as changing outdoor clothing, wearing masks and gloves, and sanitizing commonly used spaces. For some patients, precautions involved leaving their homes in New York City and temporarily relocating elsewhere.

“If I go out for groceries I wear a mask and gloves. I take my shoes off, I wash my hands, my keys, and my sunglasses. I wash anything that was outside. I keep packages in the hallway for two days, and then wash and sanitize whatever comes in the kitchen.”

“My mother died on March 17 from the virus. My sister and brother then both tested positive. To be away from them I went to live at a friend's house outside the city and self-quarantined. I had to quickly pack-up and bring everything, including my office work.”

Patients reported musculoskeletal limitations that they attributed to consequences of sheltering-in-place at home (Table 2). These were due mostly to loss of mobility from self-directed and formal exercise.

“I can’t go outside and walk for exercise; that is bad for my lupus.”

“I was seeing a physical therapist for neck and hip problems, but that has stopped.”

Patients also complained of increased pain, which they often attributed to overuse of joints from new and increased tasks. Some also wondered whether pain could be due to the virus. Other symptoms were worse cognition and difficulty concentrating.

“I have pain all day, every day. I am not sure if pain is worse because it is due to COVID.”

“I am not having a flare but I don't feel great right now. My joints are swollen; I am not sure if it is lupus or all the extra typing I am doing.”

“This whole thing is very distracting and makes it hard to concentrate.”

In addition to worsening physical symptoms, patients were forthcoming in reporting indirect detrimental effects of COVID-19 on psychological well-being, particularly from worry and stress due to several specific sources.

First, patients were very worried about contracting SARS-CoV-2. They perceived themselves to be at increased risk because of their underlying rheumatic disease and their immunosuppressive medications (Table 3).

“For me it is an autoimmune response, my antibodies attack my good cells. I think the virus would make my antibodies attack me even more.”

“I am at high risk. If I get sick, it will be hard to overcome. My immune system is weak and the medications make my system weaker. It is already busy, and if this gets added on, it is potentially fatal.”

Patients also were worried about passing the infection to others.

“I am somewhat concerned about getting it but more concerned that I would give it to someone older than me, like my parents.”

Patients also were worried about altering medications, but the direction of this concern was not uniform. In some cases, patients wondered about decreasing medications either to enhance resistance to infection or because they felt well and did not want to be overmedicated. In other cases, patients were concerned about adequate treatment for worsening symptoms.

“I had a visit with my doctor three weeks ago, she said I could probably decrease my steroids, but due to COVID maybe it is better not to change anything.”

“My doctor wants me to keep the hydroxychloroquine as is. I am in-between. I know I need more medications because my hand is swelling, it is a flare. But we will hold for now; he said to get an eye exam first.”

In addition to concern about infection, patients also were worried about the toll the pandemic had on their families. Mostly these were worries about derailment of schoolwork and social activities for children, loss of opportunities, and isolation and loss of social support for older family members (Table 3).

“Both my sons are home from college. Their varsity teams are suspended. Their psyche is affected. They spent their youth training and preparing and then something comes out of the blue and takes it from you. That is distressing for them.”

“It is a role reversal with my parents; they are now grounded. They are isolated. I got an iPad for them and our one-on-one has changed and more now is via social media. I am worried; this is not what they are used to.”

Worry about job and finances was another major concern (Table 4). Effects were noted for different occupations in different industries, as well as for educational pursuits. Worry about work led some patients to consider not only changing their current job but changing to an essential occupation to safeguard against future job and financial loss.

“This pandemic has had a monumental effect on my practice. Total destruction of my work. I don't know how I will manage when it is over.”

“I am working for no salary right now. I am furloughed. My wife was laid off. We are worried about getting our jobs back.”

In addition to worry, patients reported that stress from multiple sources was common.

“I think the biggest thing is the anxiety this creates. I am tense all the time.”

“This situation has completely altered my life. It has increased my stress.”

Some patients encountered new stressful situations in the workplace (Table 4). In some cases patients were redeployed to different work assignments and were anxious about frequently changing tasks and potential lay-offs. Others were in close proximity to individuals possibly infected with SARS-CoV-2 and were concerned about their risk of infection.

“I am a physical therapist with close proximity to patients. We were told not to wear masks. This made me extremely angry. I would have felt safer, it upset me. The policy did not make sense.”

“It is impossible to be normal again. This is mentally difficult. I am anxious and fidgety around people. I have my own office; when people come now, I ask them to stand outside my office or call.”

Increased stress at home also was common, with most patients reporting that family members were attuned to their increased risk of infection because of their rheumatic disease, and were proactive with precautions. However, in some situations patients had to insist others be more cautious. Another stressful situation was having multiple family members sheltering-in-place together for prolonged periods of time (Table 4).

“I live with my boyfriend. He is much more aware now that I explained how we should do things.”

“My husband has a coworker with a positive family member. My husband now sleeps in the other bedroom.”

“At home we have a high schooler and a college junior. We are all stuck in the house. It has been stressful to be altogether all the time.”

In addition to existing family obligations, patients reported additional stress associated with non-routine family responsibilities (Table 4). These included added financial concerns and increased infection risk while fulfilling these obligations.

“I have more family responsibilities for my grandmother, I bring her food. I also give money to my parents while I maintain my apartment, so that is more expensive.”

“My son’s teacher was infected and hospitalized. Then 5 days later my son had breathing problems and vomited. It was the end of February early March. We tried to get him tested, but they said it is not for children, save the tests for adults. I took care of him. Then shortly after that, I became sick. I had a lot of fatigue but forced myself to go to the office. The next day I could not get out of bed.”

Patients were particularly stressed by the enigmatic nature of SARS-CoV-2 (Table 4). The many unknowns were vexing, including unknowns about personal and public health risks of infection. The role of immunosuppressive medications as potentially being advantageous against inflammation contributed to uncertainty.

“A lot of things are unknown at this time. Does it affect you differently if you have a rheumatic disorder? Our antibodies are fighting ourselves, so will they try to fight the virus too?”

“I am worried when they let people out again and there is no vaccine. How will they prevent this from happening again?”

“I am stressed even though I am taking precautions. Logic begins to escape you – you have a scratchy throat and it is stressful.”

Finally, patients reported stress from hearing about the escalating pandemic from the media (Table 4). In addition to accounts of daily increases in prevalence and mortality, patients were unsettled by conflicting information and forecasts of change and uncertainties in future daily life.

“The TV and news make me stressed. I get scared and don't sleep. I have panic attacks.”

“Initially I was very worried. But now I am not so sure. Could my medications be helping me? I know there is controversy about hydroxychloroquine. There isn’t a lot of research, no one is really sure. We have to sit tight until scientists and doctors come up with a treatment, a vaccine, and understand transmission.”

Patients attributed worsening rheumatic disease symptoms to these physical and psychological effects precipitated by the pandemic. In many cases patients reported several effects that coalesced into a composite picture of more rheumatic disease symptoms (Table 3). Some patients also were unable to distinguish what would be considered usual reactions to the pandemic and what would be attributable to their disease.

“I do a lot of multitasking. I work from home, I have to handle my children’s school work, laundry, cooking. I am juggling all the time. The day seems like it never ends. It is sometimes hard to tell if this is lupus-related fatigue or just extra-work fatigue. I have always been resilient and could multitask. But this is different; it is ongoing, continuous, and it is not known when it will end. So it carries more magnitude and brings more stress. It requires more physical and mental energy to manage various aspects of everyday life.”

Discussion

In our qualitative study, patients reported physical and psychological effects from coping with the COVID-19 pandemic that they perceived contributed to symptoms of their rheumatic disease. Some effects, such as fatigue and musculoskeletal limitations, were direct contributors and overlapped with rheumatic symptoms. Other effects, such as worry and stress, were indirect contributors, which patients cited as potentiating symptoms. There were multiple sources for these effects, including perceived risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, family, work and financial issues, multitasking to fulfill diverse roles, and uncertainty about medications and what would be the future normal.

There are several limitations to our study. First, it was conducted in New York City during the height of the pandemic and may not represent the perspectives of patients in other settings or where the pandemic was not as acute. Second, participants were patients of specialty-trained rheumatologists in a tertiary care center and may differ from patients followed in other practices. Third, our qualitative questions were purposefully broad and patients likely commented on issues that were particularly salient to them at the time of the interview. Thus, they might have endorsed additional symptoms and psychological issues if they had been specifically asked about them. Fourth, patients recently had been in communication with their rheumatologists and thus may have been particularly attuned to symptoms and the potential impact of COVID-19 on their rheumatic disease.

From our study we learned that even in the absence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, patients perceived a decline in rheumatologic health due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For most patients physical and psychological effects coexisted, both contributing to worse overall health status. Implications of our study are that, in the short-term, patients may need additional medications to restore function and should receive support for psychological distress. In the long-term, patients will need assessment of disease activity with physical examination; laboratory testing also will be required to determine whether medications should be escalated to recapture disease control and halt progression. Rheumatologists also should assess long-term effects of psychological distress and, if indicated, should seek assistance from consultation with mental health and social work colleagues.

Several preliminary studies about health effects of coping with COVID-19 have been reported, and our study supports their conclusions. In one registry-based study, patients reported anxiety and fear associated with contracting the virus, expending energy to decrease risk, and uncertainty in interpreting symptoms; patients associated these reactions with worsening rheumatic symptoms [8]. Some authors have commented on psychological distress resulting from isolation and uncertainty, and the need for short- and long-term diligent surveillance and emotional support [5, 14]. Other authors have focused on long-term adverse outcomes from inactivity and recommend special attention to restoring mobility [13]. Newly established registries designed to track COVID-19 outcomes from the patients’ point of view will provide longitudinal data on rheumatic disease symptoms and impact on mental health [16].

Our study provides a detailed account of challenges patients with rheumatic disease encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic. Strengths of this study include patients had diverse diagnoses, were recruited from different rheumatology practices, and identified a spectrum of salient rheumatologic issues. In addition, this study took place in real-time during a narrow period at the height of the pandemic and thus was not affected by recall bias and was less affected by rapidly shifting COVID-19 revelations. We learned that coping with the pandemic was associated with physical and psychological effects, even among patients not infected with SARS-CoV-2. According to patients, these effects adversely impacted their rheumatic diseases. Clinicians will need to ascertain the long-term sequelae of these consequences and determine what therapeutic and psychosocial interventions are indicated.

References

Berkowitz M, Inui TS. Making use of qualitative research techniques. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):195-199.

Campbell JL, Quincy C, Osserman J, Pedersen OK. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol Methods Res. 2013;42(3):294-320.

Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 4th. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Pub; 2018.

de Brouwer SJ, Kraaimaat FW, Sweep FC, et al. Experimental stress in inflammatory rheumatic disease: a review of psychophysiological stress responses. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010; 12(3):R89. :https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3016

Décary S, Barton JL, Proulx L, et al. How to effectively support patients with rheumatic conditions now and beyond COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 13]. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;https://doi.org/10.1002/acr2.11152.

Hadi MA, Closs SJ. Ensuring rigour and trustworthiness of qualitative research in clinical pharmacology. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:641-646.

Hassett AL, Clauw DJ. The role of stress in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(3):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3024

Michaud K, Wipfler K, Shaw Y, et al. Experiences of patients with rheumatic diseases in the United States during early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(6):335-343. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr2.11148

Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Res. 2015;25(9):1212-1222.

Morse JM. “Data were saturated…” Qualitative Health Res. 2015;25(5):587-588.

Nagaraja V, Mara C, Khanna PP, et al. Establishing clinical severity for PROMIS measures in adult patients with rheumatic diseases. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:755-764.

Pawluch D, Neiterman E. What is grounded theory and where does it come from? In: Bourgeault I, Dingwall R, De Vries R, eds. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research. London.: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2010.

Pinto AJ, Dunstan DW, Owen N, Bonfá E, Gualano B. Combating physical inactivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(7):347-348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-020-0427-z

Pope JE. What does the COVID-19 pandemic mean for rheumatology patients? [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 30]. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2020;1-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40674-020-00145-y

Saletkoo LA, Pauling JD. Qualitative methods to advance care, diagnosis, and therapy in rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Amer. 2018;44:267-284.

Sirotich E, Dillingham S, Grainger R, Hausmann JS, COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance Steering Committee. Capturing patient-reported outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: development of the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance Patient Experience Survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(7):871-873. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24257

Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory Research. 2nd Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998.

Ventura I, Reid P, Jan R. Approach to patients with suspected rheumatic disease. Prim Care. 2018;45:169-180.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Carol A. Mancuso, MD, Roland Duculan, MD, Deanna Jannat-Khah, DrPH, MSPH, Medha Barbhaiya, MD, MPH, Anne R. Bass, MD, and Bella Mehta, MBBS, MD, declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human/Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in this study.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Additional information

Level of Evidence: Level III: Prospective Qualitative Study

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mancuso, C.A., Duculan, R., Jannat-Khah, D. et al. Rheumatic Disease-Related Symptoms During the Height of the COVID-19 Pandemic. HSS Jrnl 16 (Suppl 1), 36–44 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-020-09798-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-020-09798-w