Abstract

With the increased spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection, more patients with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) are being reported worldwide. This systematic review with meta-analysis aims to analyse the clinical features, proposed pathogenesis and current treatment options for effective management of children with this novel entity. Electronic databases (Medline, Google Scholar, WHO, CDC, UK National Health Service, LitCovid, and other databases with unpublished pre-prints) were extensively searched, and all articles on MIS-C published from January 1, 2020, to October 10, 2020, were retrieved. English language studies were included. This systematic review analysed 17 studies with 992 MIS-C patients from low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) and developed countries (France, the UK, Italy, Spain, Chile and the US CDC data). Fever (95%) was the most common clinical manifestation followed by gastrointestinal (78%), cardiovascular (75.5%), and respiratory system (55.3%) involvement. Laboratory or epidemiologic evidence of inflammation and SARS-CoV-2 infection was present. Though the exact pathogenesis remains elusive, virus-induced post-infective immune dysregulation appears to play a predominant role. Features resembling Kawasaki disease, toxic shock syndrome or macrophage activation syndrome were present; 49% had shock; 32% had myocarditis; 18% had coronary vessel abnormalities and 9% had congestive cardiac failure. Sixty-three percent of the patients were admitted in paediatric intensive care unit (PICU); 63% received intravenous immunoglobulin, 58% received corticosteroids and 19% received alternate agents like tocilizumab; there were 22 (2.2%) deaths. Only 9/144 children in LMICs received tocilizumab that was significantly less than children in developed countries (p < 0.0001). This systematic review delineates and summarises recently published data on MIS-C from LMICs and developed countries. Although most needed PICU admission and received treatment with IVIG and steroids, most of the patients survived. Significantly fewer patients in developing countries received tocilizumab therapy than those in developed countries. It is crucial for clinician to recognise MIS-C, to differentiate it from other defined inflammatory conditions and initiate early treatment. Further studies are needed for long-term prognosis, especially relating to cardiac complications of MIS-C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 initially started from Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and rapidly spread over 189 countries within 11 months. As of 16 November, 2020, there are more than 55 million confirmed cases and more than one million deaths [1]. Paediatric cases account for only 2.1–7.8% of total confirmed COVID-19 cases [2]. There is still uncertainty about the actual disease burden among children, as most children remain asymptomatic, and most institutions focus upon viral testing of symptomatic or close contact of patients. Initially thought to be milder in children, the proportion of children hospitalised due to COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory conditions is increasing worldwide. WHO, CDC and other Health Organisations have released scientific information on this 5-month-old condition multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), also labelled as paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS) tabulated in Table 1 [2,3,4]. The evidence from published literature on MIS-C clinical profile (fever, prominent abdominal symptoms, hypotension and shock), laboratory profile (lymphopenia, marked elevation of inflammatory markers) and cardiac findings (elevated troponin/N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), with echocardiographic findings of left ventricular myocardial dysfunction, pericarditis or coronary abnormalities) shows promising outcome and quick resolution of inflammation [5]. There is an overlap of clinical characteristics of MIS-C with other inflammatory syndromes in children, including Kawasaki disease (KD), toxic shock syndrome (TSS) and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) which is new challenge in this pandemic.

Good description of disease epidemiology is now available through rapidly published extensive literature, but we still need to understand its pathogenesis, clinical progression from mild to more serious categories including long-term outcome of MIS-C patients due to coronary artery damage, and the role of anti-inflammatory and immunomodulator treatment in improving prognosis. In this systematic review, we critically evaluate and summarise the recent evidence to complement the understanding of MIS-C, the best therapeutic approach for improved survival and implications for future research.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

Medline, Google Scholar, WHO, CDC, the UK National Health Service, LitCovid and unpublished database in BioRxiv.org and MedRxiv.org were searched for articles published from 1 January 2020 to 30 October 2020, using the Medical Subject Headings terms “SARS virus”, “coronavirus”, “systemic inflammatory response syndrome”, “Covid-19”, “infant”, “newborn”, “child”, “adolescent”, “multisystemic inflammatory syndrome”, “MIS-C” and related terms. Relevant references cited in the articles were reviewed. Articles published in English were included. Search results were compiled in accordance with the quality standards for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analysis of observational studies. The risk of bias for all eligible studies was accessed according to the STROBE reporting guideline. Pooled meta-analysis of data was done on statistical Software Stata version 13.

Results

Out of total 386 identified studies, data of 992 children from 17 studies was included in this systematic review, which included 144 patients from low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), CDC data from the USA and published data from France, the UK, Italy, Spain, Chile and Japan [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] (PRISMA flow diagram Fig. 1). The M:F ratio was 1.37:1, with 567 males and 412 females. Median age was 7 years, 6 months (IQR 6–9 years), the youngest 2 weeks, and the oldest was 20 years of age. MIS-C cases started appearing around 1 month after COVID-19 peak in the population. Forty-eight percent (456 out of 948) had antibodies [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, 15, 16, 19,20,21,22], while RT-PCR was positive in 263 out of 948 (28%) patients. Twenty-three percent had both RT-PCR and Serology positive [6, 7, 12,13,14, 16, 21]. Out of 743 cases, 76 (10%) patients had contact history with COVID patients [6, 9, 11, 12, 15,16,17,18, 21, 22]. Fever was the most common reported symptom in 95%, followed by gastrointestinal (78%), cardiovascular (75.5%), respiratory system (55.3%), and CNS (30.6%) involvement, while 19.6% patients had acute kidney injury. KD-like manifestation was seen among 225 patients, with skin rash observed in 59% and conjunctivitis in 52% patients (Supplementary Information). Table 2 depicts the pooled meta-analysis from all included studies.

Pathophysiology of MIS-C and Link with COVID-19

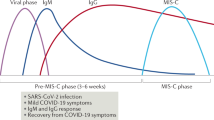

Published literature has pointed out different phenotypes of MIS-C patients including fever with inflammation, shock with MODS and myocarditis, and picture of classical KD [6, 8, 23]. Age younger than 1 year, high viral load and chronic comorbidities are risk factors for increased severity [24]. Most reports of this inflammatory illness among children followed peak of COVID-19 infections by 4–6 weeks [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17, 19,20,21,22]. A high proportion of patients with positive serology suggest antibody-dependent enhancement of acquired immune response to virus rather than direct viral replication has a major role. The role of a particular genetic locus [25] and some ethnic groups (e.g., Hispanic and African) has been associated with more severe disease [23, 26]. Even though the exact pathophysiology of this new entity is not known, the evidence which has emerged from recent literature is summarised in Fig.2.

Binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 facilitates entry of SARS-CoV-2 virus inside cell, this enzyme is highly expressed in nasal cells, alveolar cells of lungs, cardiac myocytes, and the vascular endothelium [23, 25]. Viral infection stimulates the neutrophils to form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and trap the virus triggering uncontrolled inflammation and thrombosis with elevated d-dimer or fibrinogen as seen among severe COVID-19 and MIS-C patients [27]. Viral antigen expression on infected cells and formation of anti-spike IgG immune complexes also activate inflammation leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure [23].

Management of MIS-C

With long-term outcome and risk of coronary aneurysm still unknown among MIS-C patients, lower treatment threshold is adopted based upon “Best Guess” of institutions expertise in treating other immunological disorders. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) MIS-C and COVID-19-Related Hyperinflammation Task Force have released treatment guidelines [28], expected to be modified with increasing evidence. All sick children and/or suffering from immunodeficiency, cardiac or pulmonary conditions should be admitted in hospital, and to be managed as suggested in protocol Fig. 3. Few may even need intensive care under a multidisciplinary team of paediatric infectious disease, cardiology, immunology, rheumatology, haematology and intensive care specialists. In our systematic review, 63% children [6,7,8,9,10,11, 13,14,15,16,17, 20,21,22] were admitted in PICU, 33% required invasive ventilation [6,7,8,9, 12,13,14,15, 19, 20, 22]. Patients with mild symptoms and/or well-appearing (normal vital signs and reassuring physical examination) can be managed in OPD. Close follow-up should be ensured, and if fever persists, clinical assessment and laboratory testing may be repeated. Universal infection control should remain a priority to limit transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Cardiovascular System Involvement

In this review, 307 out of 658 (47%) patients presented with significantly elevated troponin or BNP [6, 8, 9, 14, 15, 17, 20], indicating myocardial cell injury, and 11 out of 747 (1.4%) patients developed arrhythmia [8, 12]. Abnormal ECHO with left ventricle dysfunction was observed among 337 out of 823 (41%) patients [6, 8, 9, 12,13,14,15, 18, 20,21,22]. A total of 276 out of 870 patients (32%) had myocarditis [6,7,8,9,10, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18, 20,21,22], and 146 out of 709 (21%) patients had pericardial effusion [6, 9, 12,13,14, 16, 18, 21, 22]. Coronary artery abnormality was detected among 143 out of 802 (18%) patients [6, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18,19,20,21], 19.4% (20 out of 103) had coronary dilatation [12,13,14, 18], whereas aneurysm was seen in 17.8% (23 out of 129) patients [8, 9, 11,12,13, 20, 22]. Furthermore, 357 out of 725 (49%) patients presented with hypotension with shock [6, 8, 9, 12, 13, 16, 17, 20, 22] and 9% had congestive cardiac failure [6, 13, 16, 17, 21, 22].

Immediate echocardiography to assess cardiac function and general supportive care with attention to vital signs, hydration, electrolytes and metabolic status plays crucial part in the survival of children presenting with acute myocarditis, arrhythmias and hemodynamic compromise. Shock should be aggressively managed with volume expansion and vasoactive drugs epinephrine or norepinephrine, while taking caution to avoid fluid overload. Intravenous diuretics and inotropic agents, adding milrinone, are useful to treat significant LV dysfunction. Prophylactic antithrombotic therapy should be started in patients with moderate to severe manifestations of MIS-C. Arrhythmias should be promptly detected and treated. In cases of fulminant disease, mechanical hemodynamic support in the form of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or a ventricular assist device will be required. High-dose IVIG may be considered after cardiac function is restored [28].

Drug Therapy

-

1.

Intravenous immunoglobulin: Use of IVIG is recommended to treat patients with KD-like features, those with shock, and cardiac involvement with depressed LV function or coronary artery abnormalities (dilation or aneurysm), and if the patient’s clinical status worsens or they remain persistently febrile with elevated inflammatory markers [28]. Dose is 2 g/kg (max 70–90 g). Serologic testing for SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens should be done prior to administration of IVIG. In this review, 551 out of 872 (63%) MIS-C patients received IVIG [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, 18,19,20,21,22]; the vast majority of them were discharged without cardiac abnormality.

-

2.

Steroids: Glucocorticoids are used in addition to IVIG in MIS-C patients with refractory shock, KD-like features, persistent fever and rising inflammatory markers. The UK RECOVERY trial has shown survival benefit with dexamethasone in ventilated patients with severe respiratory complications from COVID-19 [29]. In our review, 512 out of 872 (58%) of patients were treated with glucocorticoids with rapid recovery [6, 8, 12, 13, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Steroids can be given as intravenously (IV) methylprednisolone, oral dose of prednisolone (2 mg/kg) or pulse doses of glucocorticoids (30 mg/kg pulse) [28].

-

3.

Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy: Low-dose aspirin (3–5 mg/kg/day; max 81 mg/day) is recommended for hospitalised moderate to severe MIS-C patients with KD-like features and/or thrombocytosis (platelet count ≥ 450,000/𝜇L), raised d-dimers, and high fibrinogen concentration with increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). It is to be continued until normalisation of platelet count and confirmed normal coronary arteries at ≥4 weeks after diagnosis. Avoid aspirin in patients with a platelet count ≤ 80,000/𝜇L. Patients with documented thrombosis or with coronary artery aneurysm and z score of ≥ 10.0 or an ejection fraction (EF) < 35% should receive enoxaparin in addition to low-dose aspirin [28]. Sixty-seven percent patients (505 out of 754) had elevated d-dimer [6, 8, 10, 12,13,14, 16, 17, 20, 21], and 284 patients received antithrombotic therapy [6, 9, 11, 13, 14, 16, 20, 21] in this review.

-

4.

Immunomodulators: Infliximab (anti-tumour necrosis factor drug), Anakinra, canakinumab (IL-1 receptor antagonist) and tocilizumab (IL-6 antagonist) are alternative options for treatment of MIS-C patients who are refractory to IVIG, have glucocorticoids with enlarging coronary aneurysm or in patients with contraindications to these treatments [30]. However, the risk for bacterial and fungal infections remains higher. In this systematic review, immunomodulators were used in 141 out of 752 (19%) patients. [6, 8, 10, 14, 15, 21, 22]. Treatment should be given under paediatric rheumatologist supervision preferably in the context of a clinical trial whenever possible.

-

5.

Antiviral drugs: The role of antiviral drugs in the management of MIS-C is uncertain. Remdesivir inhibits the actively replicating virus and has been shown to shorten COVID-19 illness duration in adults. MIS-C likely represents a post-infectious complication rather than active infection; however, some children do have positive RT PCR for SARS-CoV-2 where antiviral therapy can benefit [28].

Outcome and Follow-up

MIS-C patients often require special care and aggressive treatment; however, most have favourable outcome. In this systematic review, there were only 22 deaths (2.2%) [6,7,8, 12, 13, 15, 18, 20]. Most deaths happen among those with co-morbid diseases (Supplementary Information data). Children can be discharged from the hospital once afebrile and normotensive, with normal inflammatory markers. The medium to long-term outcomes, such as the sequelae of coronary artery aneurysm formation following MIS-C, remain unknown; hence, close follow-up is very important.

Treatment Choices for Resource-Limited Countries

In this systematic review of MIS-C, 144 patients have been reported from India, Pakistan, Iran, Brazil and South Africa [10, 11, 13,14,15,16,17,18, 20, 22]. Most of the immunomodulator drugs advised to treat MIS-C are either unavailable or unaffordable in LMICs. IVIG and steroids were each used in 92 (63.9%) patients. Compared to children in developed countries, a very few patients in LMICs only 7 out of 144 (4.8%) received tocilizumab (p < 0.0001). Comparing data from Asian countries [10, 11, 13,14,15,16, 18], 59 out of 100 (59%) received IVIG, while 64% received steroids, and only 5 patients received immunomodulators, while data from South Africa and Latin American countries [17, 20, 22] showed 33 out of 44 (75%) received IVIG, and 63.6% received steroids; only 2 patients received toclizumab. Steroids are cheaper and are a more accessible option in LMICs, but due to high prevalence and limited diagnostic facilities to exclude tuberculosis and HIV infection in these countries, the potential to induce broad immunosuppression with steroids might be hazardous. More research on right type, dose, route and duration of steroid use in children hospitalised with severe MIS-C disease is needed. The ongoing international study comparing the best available treatment depending on clinician preference and drug availability [31] might provide information on the treatment options available in LMICs in the future.

Conclusion

Most MIS-C patients associated with SARS survive with only 2.2% deaths in this systematic review. Most patients had recovery of ventricular function with resolution of coronary vessels abnormalities. Over time, post-discharge follow-up data will be available, and long-term complications due to MIS-C will be known. There is no unique clinical feature or diagnostic test to differentiate MIS-C from other defined inflammatory conditions. KD typically affects infants or young children less than 5 years, whereas MIS-C patients tend to be older from 8 up to 15 years old. Gastrointestinal symptoms, myocardial dysfunction and shock are more common in MIS-C compared to that in classic KD. Both diseases have almost the same laboratory abnormalities; however, D-dimer, Ferritin, Troponin/BNP and CRP levels are higher in MIS-C. Considering the current pandemic of SARS-CoV-2, it is crucial for the clinician to keep MIS-C as one of the differential diagnoses in a sick child. The multi-faceted nature of this disease underlines the need for early recognition and multispecialty care and management to avoid rapid compromise. Treatment of MIS-C is complicated, newer guidelines will be released as more information on disease evolves over time. The disease can be prevented by public health measures that control COVID-19. Nonetheless, further studies are needed to depict the long-term prognosis, especially relating to coronary artery aneurysm in MIS-C. Guidelines for patient management in LMIC countries need to be more specified, due to difficulty in the procurement of immunomodulators and IVIG.

Data Availability

Systematic review; data was submitted as Supplementary text.

References

WHO. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. Covid-19 Dashboard2020 [cited 2020, Nov 16];1–1. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/

CDC. Information for healthcare providers about multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020, Nov 9];Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mis-c/hcp/

World Health Organization. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents temporally related to COVID-19. 2020.

Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health. Guidance—Pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19. 2020. Available from: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/guidance-pediatric-multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-temporally-associated-covid-19. Accessed November 5, 2020.

Kaushik A, Gupta S, Sood M, Sharma S, Verma S. A systematic review of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(11):e340–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000002888.

Bialek S, Boundy E, Bowen V, Chow N, Cohn A, Dowling N, et al. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) — United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343–6.

Belot A, Antona D, Renolleau S, Javouhey E, Hentgen V, Angoulvant F, et al. SARS-CoV-2-related paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome, an epidemiological study, France, 1 March to 17 May 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(22):2001010. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.

Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, Kaforou M, Jones CE, Shah P, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;324(3):259–69.

Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni A, Martelli L, Ruggeri M, Ciuffreda M, et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1771–8.

Balasubramanian S, Nagendran TM, Ramachandran B, Ramanan AV, Balasubramanian SNT, Ramachandran BRA. Hyper-inflammatory syndrome in a child with COVID-19 treated successfully with intravenous immunoglobulin and tocilizumab. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57(7):681–3.

Acharyya BC, Acharyya S, Das D. Novel coronavirus mimicking Kawasaki disease in an infant. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57(8):753–4.

Moraleda C, Serna-Pascual M, Soriano-Arandes A, Simó S, Epalza C, Santos M, et al. Multi-inflammatory syndrome in children related to SARS-CoV-2 in Spain. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa1042. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1042 Epub ahead of print.

Sadiq M, Aziz OA, Kazmi U, Hyder N, Sarwar M, Sultana N, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19 in children in Pakistan. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(10):e36–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30256-X.

Dhanalakshmi K, Venkataraman A, Balasubramanian S, Madhusudan M, Amperayani S, Putilibai S, et al. Epidemiological and clinical profile of pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome - temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS) in indian children. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57(11):1010–4.

Jain S, Sen S, Lakshmivenkateshiah S, Bobhate P, Venkatesh S, Udani S, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19 in Mumbai, India. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57(11):1015–9.

Mukund B, Sharma M, Mehta A, Kumar A, Bhat V. Pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 – an emerging problem of PICU: a case series. J Pediatr Crit Care. 2020;7(5):271–5.

Prata-Barbosa A, Lima-Setta F, dos Santos GR, Lanziotti VS, de Castro REV, de Souza DC, et al. Pediatric patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units in Brazil: a prospective multicenter study. J Pediatr. 2020;96(5):582–92.

Mamishi S, Movahedi Z, Mohammadi M, Ziaee V, Khodabandeh M, Abdolsalehi MR, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in 45 children: a first report from Iran. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e196. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095026882000196X Epub ahead of print.

Iio K, Uda K, Hataya H, Yasui F, Honda T, Sanada T, et al. Kawasaki disease or Kawasaki-like disease: influence of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Japan. Acta Paediatr. 2020:apa.15535. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15535 Epub ahead of print.

de Farias ECF, Pedro Piva J, de Mello MLFMF, do Nascimento LMPP, Costa CC, Machado MMM, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with coronavirus disease in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 39(11):e374-e376. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000002865.

Torres JP, Izquierdo G, Acuña M, Pavez D, Reyes F, Fritis A, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): report of the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of cases in Santiago de Chile during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:75–81.

Webb K, Abraham DR, Faleye A, McCulloch M, Rabie H, Scott C, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in South Africa. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(10):e38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30272-8.

Lawrensia S, Henrina J, Wijaya E, Suciadi LP, Saboe A, Cool CJ. Pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2: a new challenge amid the pandemic. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2(11):2077–85.

Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–5.

Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–74.

Pouletty M, Borocco C, Ouldali N, Caseris M, Basmaci R, Lachaume N, et al. Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 mimicking Kawasaki disease (Kawa-COVID-19): a multicentre cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(8):999–1006.

Mozzini C, Girelli D. The role of neutrophil extracellular traps in Covid-19: only an hypothesis or a potential new field of research? Thromb Res. 2020;191:26–7.

Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, Gorelik M, Lapidus SK, Bassiri H, et al. American College of Rheumatology Clinical Guidance for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated With SARS-CoV-2 and Hyperinflammation in Pediatric COVID-19: Version 1. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(11):1791–805. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41454.

RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 - preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020:NEJMoa2021436. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 Epub ahead of print.

Dulek DE, Fuhlbrigge RC, Tribble AC, Connelly JA, Loi MM, El Chebib H, et al. Multidisciplinary guidance regarding the use of immunomodulatory therapies for acute coronavirus disease 2019 in pediatric patients. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020:piaa098. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piaa098 Epub ahead of print.

ISRCTN - ISRCTN69546370: Best available treatment study for inflammatory conditions associated with COVID-19 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 21];Available from: http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN69546370

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Mangla Sood, Seema Sharma, Ashlesha Kaushik and Kavya Sharma. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Mangla Sood and Ishaan Sood jointly. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Consideration

This manuscript is an original work prepared by the authors and does not overlap with any previous publications. This manuscript has not been submitted for publication and will not be submitted to any other journal while under consideration by SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine.

Ethics Approval

N/A

Consent to Participate

N/A

Consent for Publication

N/A

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Covid-19

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(53.4 kb docx)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sood, M., Sharma, S., Sood, I. et al. Emerging Evidence on Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection: a Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 3, 38–47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00690-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00690-6