Advertisement

Grab your lab coat. Let's get started

Welcome!

Welcome!

Create an account below to get 6 C&EN articles per month, receive newsletters and more - all free.

It seems this is your first time logging in online. Please enter the following information to continue.

As an ACS member you automatically get access to this site. All we need is few more details to create your reading experience.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

Not you? Sign in with a different account.

ERROR 1

ERROR 1

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

ERROR 2

Password and Confirm password must match.

If you have an ACS member number, please enter it here so we can link this account to your membership. (optional)

ERROR 2

ACS values your privacy. By submitting your information, you are gaining access to C&EN and subscribing to our weekly newsletter. We use the information you provide to make your reading experience better, and we will never sell your data to third party members.

Business

Covid-19

The next generation of COVID-19 antivirals

Several firms are developing follow-ups to the Pfizer and Merck pills

by Jared Whitlock, special to C&EN

March 28, 2022

| A version of this story appeared in

Volume 100, Issue 11

Enanta Pharmaceuticals wasn’t the first. But it hopes to be the best.

The Massachusetts-based company has an antiviral for COVID-19 in an early-stage clinical trial that it expects will be more potent and convenient than options currently on the market.

Support nonprofit science journalism

C&EN has made this story and all of its coverage of the coronavirus epidemic freely available during the outbreak to keep the public informed. To support us:

Donate Join Subscribe

And Enanta isn’t alone. Several small drug companies, including Shionogi & Co., Pardes Biosciences, and Model Medicines, are racing to launch next-generation antivirals that target SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Meanwhile, Pfizer and Merck & Co., which released pioneering COVID-19 antivirals, already have follow-on products in their pipelines.

It’s difficult to forecast events with COVID-19. Will the virus become endemic? Will new variants emerge? No matter what, the antiviral market will be here for years, according to experts, who say it’s imperative to develop molecules aimed at different targets in case antiviral resistance emerges.

“We knew that we likely wouldn’t be the first,” Enanta CEO Jay R. Luly says. “But that’s OK.”

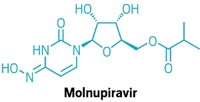

Last year, Pfizer and Merck launched COVID-19 antiviral pills in a feat of rapid drug discovery and development. But both have shortcomings. Pfizer’s Paxlovid(nirmatrelvir and ritonavir), which reduces risk of hospitalization and death by 89%, can interfere with commonly prescribed drugs. Lagevrio (molnupiravir), developed by Merck and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, is only moderately effective. It lowers hospitalization and death risk by around 30%, and it carries reproductive risks.

Other drugmakers have an opportunity to launch drugs with better safety profiles and increased efficacy, according to a report released last month by the investment bank SVB Leerink.

For example, Leerink says, Enanta’s candidate, EDP-235, may exhibit more in vitro potency against the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 than other antivirals, though clinical trial data will be the true judge. EDP-235 started a Phase 1 trial in February that’s measuring safety; Enanta plans to report data in the second quarter.

“We believe the COVID-19 landscape is not a zero-sum game, and even with vaccines and antibodies available, with the right clinical profile new antivirals could carve out a solid niche,” Leerink says. “As COVID-19 becomes more endemic, the treatment paradigm could shift in the next one to two years from treating urgent severe COVID-19 cases in hospitals to more proactive testing and treating of mild/moderate cases in the outpatient setting.”

Meanwhile, US government programs aim to make antivirals more accessible. Under a recently launched initiative called Test to Treat, high-risk patients with COVID-19 symptoms can get tested at certain pharmacies and if positive walk out with a free course of antivirals. The process is intended to be easier than securing a doctor’s prescription, and it could boost antiviral demand.

The antivirals now on the market consist of several pills that must be taken twice a day over 5 straight days, soon after a positive COVID-19 test. EDP-235 is among the next-generation antivirals that are intended to be once-a-day pills, increasing the chance of patient compliance and decreasing the chance of unfinished treatments that could spark antiviral resistance.

“If you’re not maintaining the doses that you’re targeting, you could potentially select for resistance in the virus,” says Sara Cherry, a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. She notes that drug resistance rendered certain anti-flu medications ineffective and that the same could happen with COVID-19 antivirals.

“That’s also why it would be good to have multiple antivirals, so it would be harder for the virus to evolve resistance,” Cherry says. And the hope is that COVID-19 antivirals continually improve, much like drugs for hepatitis C and HIV.

“The first hep C products moved the needle forward,” Luly says. “But it was the later generations that made efficacy rates go even higher than people could ever imagine.”

In fact, Enanta used proceeds from its own hepatitis C drug—a next-generation product that the firm licensed to AbbVie—to fund its COVID-19 antiviral program. In the early days of the pandemic, Enanta sifted through its drug library with the hope of repurposing a program for COVID-19. Nothing emerged; unlike Pfizer, the company had no experience working with coronaviruses. But Enanta was versed in protease inhibitors that prevent a virus from replicating in infected cells.

EDP-235 targets the virus’s 3CL protease, also known as the main protease. Enanta says it’s among the most potent direct-acting antivirals in development for SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition to its once-daily-dosing potential, the compound has demonstrated activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants and all other known human coronaviruses, the firm says.

“When we saw a nice protease target in COVID, we went right after it,” Luly says.

Shionogi’s S-217622 is also a protease inhibitor. In February, the Japanese drugmaker filed for conditional approval in its home country after completing Phase 2b of a Phase 2/3 trial. The company, which declined an interview request, has stated that it will also seek approval elsewhere, including in the US.

According to the Leerink report, S-217622 seems to have lower in vitro potency than other antivirals but the highest bioavailability—the rate and extent of absorption and circulation in the body.

Pfizer expects Paxlovid, another protease inhibitor, to generate $22 billion in sales this year. But the company isn’t getting complacent. It plans to produce a next-generation antiviral that does not include ritonavir, which is in Paxlovid along with the antiviral nirmatrelvir. Ritonavir is an HIV drug that allows nirmatrelvir to remain active in the body longer, but it can interfere with other medications. Human trials are expected in the second half of this year.

Pfizer declined an interview request, but in an emailed statement the company says it remains confident in Paxlovid’s clinical profile because of clinical and in vitro data that confirm “activity across the current variants of concern, including Omicron.”

“That said, we want to stay ahead of the virus, and it is precedented that proteases can mutate once treated with an inhibitor, although we have not seen anything of concern clinically,” the statement says. “We are advancing work on a potential next generation SARS-CoV-2 antiviral with the aim of achieving similar high clinical efficacy and pan-coronavirus design properties that maintain activity, with a favorable safety profile, and counter potential viral resistance, but without the need for ritonavir boosting.”

Merck’s molnupiravir targets a different way that the virus replicates itself: RNA polymerase. Another antiviral, Gilead Sciences’ Veklury (remdesivir), also goes after RNA polymerase but requires lengthy intravenous infusions. Merck, which declined an interview request, notes that it also has a protease inhibitor in preclinical development.

Pardes Biosciences, another drugmaker with a protease inhibitor for COVID-19, anticipates starting a Phase 2/3 trial in mid-2022. The company describes its compound, PBI-0451, as targeting the viral main protease.

Academic institutions and drug developers have sought to repurpose existing drugs or drug candidates to fight COVID-19. That’s also what Model Medicines is doing, with the difference that it narrowed its search to compounds that were not originally developed for infectious disease.

Through machine learning and artificial intelligence, Model Medicines found MDL-001. The molecule was previously shown to be safe in a Phase 1 trial for an undisclosed indication but abandoned by the original drugmaker because of shifting priorities, according to CEO Daniel Haders.

Model Medicines now hopes that MDL-001 could be a once-daily pill for COVID-19, though the company declines to describe the mechanism of action. “We wanted a drug that potentially was so safe and well tolerated that it can be dosed to any patient groups regardless of variant, regardless of sex, regardless of age, regardless of comorbidities,” Haders says.

Model Medicines recently said that strong preclinical data landed MDL-001 an evaluation agreement with the US National Institutes of Health’s Antiviral Program for Pandemics, accelerating the company’s push toward the clinic. The NIH program launched with more than $3 billion to develop next-generation treatments, including those for future viral threats.

But it’s growing more complicated to test next-generation antivirals. The pool of clinical trial participants shrinks as more people get vaccinated or take antivirals. In response, some antiviral companies have moved clinical trials to countries where vaccine uptake isn’t as high, a playbook also used by vaccine makers that entered the game later.

Eventually, instead of conducting placebo-controlled trials, regulators may compare an antiviral candidate with one that’s already authorized—a higher bar for demonstrating efficacy, the Leerink report says.

“It’s clear that every month that goes by, clinical trial design is evolving,” says Davey Smith, chief of infectious diseases and global health at the University of California San Diego and a clinical adviser for Model Medicines. “And it has to evolve, because the pandemic itself is evolving.”

As immunity to COVID-19 wanes, herd immunity becomes elusive, Smith adds. “I think COVID is going to be around for the rest of my career,” he says. “We’ll want to develop more tolerable, easier-to-get drugs along the way.”

Jared Whitlock is a freelance writer who covers health care and biotech.

Join the conversation

Contact the reporter

Submit a Letter to the Editor for publication

Engage with us on Twitter