The psychological mechanism linking life satisfaction and turnover intention among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

COVID-19 challenged and brought turmoil to the healthcare workers’ mental and psychological well-being. Specifically, they are feeling tremendous pressure and many of them worry about their work conditions and even intent to leave them. In this situation, it is of utmost for them to satisfied their lives during the challenging situation.

OBJECTIVE:

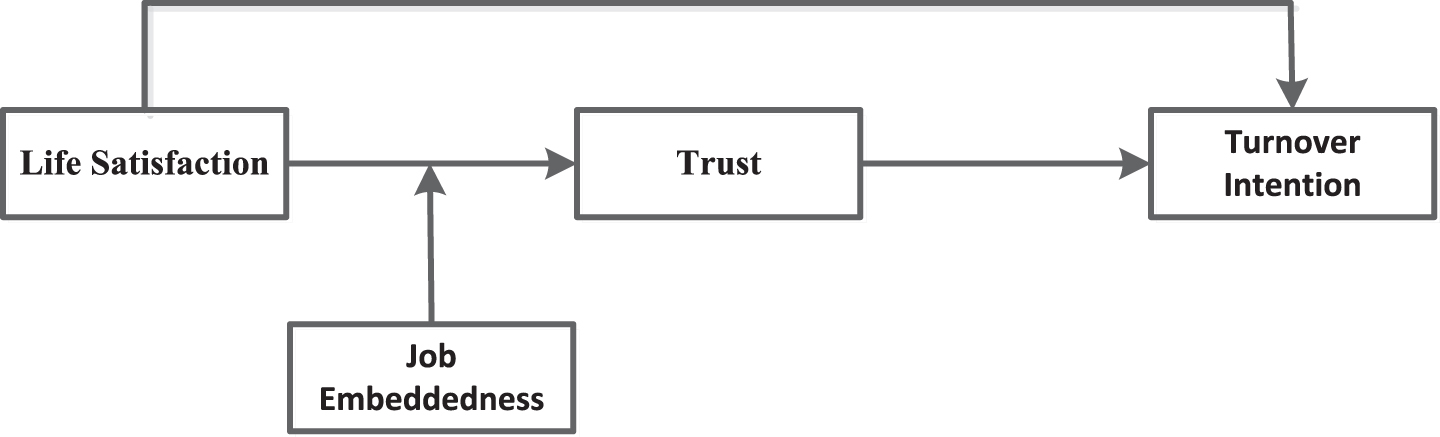

This paper explores the relationship of life satisfaction with healthcare workers' turnover intention during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was hypothesized that this relationship would be mediated by trust climate, and this mediation association would be stronger when workers experience job embeddedness in the workplace.

METHODS:

Survey data were collected from the 520 healthcare workers. A moderated mediation examination was employed to test the hypotheses.

RESULTS:

Results revealed that life satisfaction is positively related to a trusting climate that, in turn, is negatively related to workers’ turnover intention. Moreover, the association between life satisfaction and turnover intention was moderated by job embeddedness.

CONCLUSIONS:

Focusing on improving healthcare workers’ job embeddedness and increasing their trust climate might enhance life satisfaction and reduce turnover intention. The implications of the findings are also discussed for research and practice.

1Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has halted all the economic activity globally. The impact of the novel coronavirus virus on the economy, jobs, and the overall lives of people around the globe is unprecedented [1]. This disease’s exponential effect has caused huge scale closing of economies, uncomfortable living adjustments, loss of employment, and the unfortunate death of loved ones [2]. Specifically, the healthcare workforce is facing unprecedented pressure from these stressors, including but not limited to the huge workload, work incivility, moral dilemmas, inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE), virus exposure, despair, discrimination, and isolation from family [3]. In this vein, the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to major challenges in workers’ recruitment and retention for most industries. Accordingly, Ng et al. reported that healthcare workers perceive a high level of threat of easily spread COVID-19. Healthcare workers not only face a persistent threat of contracting COVID-19, they also see patients and as well as their fellow healthcare workers’ deaths on a daily basis, which is itself a distressing experience. Healthcare workers perceived risk, feelings of helplessness, and psychological strain have headed them to reconsider their career choices [4], which may develop turnover intention.

Turnover intentions refer to workers’ intention to start planning and thinking of leaving their present job and organization for different reasons [5]. Most healthcare workers working in underdeveloped countries are at great risk of contracting the virus due to the absence of proper protective equipment (PPE), leading to an increase in their intention to quit [3].

Recently many studies have reported that greater importance given to life satisfaction associated with positive job-related outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic situation [6, 7]. In this crucial time, the study of life satisfaction, or happiness,” has become a thriving area of research, especially in the field of organizational behavior [8]. There is evidence that workers with a high level of life satisfaction are likely to be highly motivated, and become more efficient and effective at work, resulting in less likely showing to develop turnover intention [9]. Furthermore, previous research highlights that life satisfaction is associated with lower turnover intentions [10, 11], and in the meanwhile a meta-analysis [12] indicated that there were only 48 articles published in the area of life satisfaction until June 2011, when the key keyword of life satisfaction search in the abstracts of management discipline in six journals (Academy of Management Journal, Journal of Applied Psychology, Organization Science, Personnel Psychology, Journal of Management, and Administrative Science Quarterly). Subsequently, [10] argued that non-work related well-being (life satisfaction) are significantly related turnover intention, that was unfortunately ignored by traditional literature.

Therefore, further research is needed to elucidate the effect of life satisfaction on turnover intention. The existing research uses the resource maintenance model to explicate the psychological mechanism that life satisfaction is linked to turnover intention, but we posited that is not ample. Furthermore, Downey et al. [13] argue that wellbeing has been disputed in literature and also premised, to some extent, on the reciprocity norm of the social exchanges. Subsequently, workers are less likely to show behavior towards negative workplace outcomes like turnover intention when they are exchange relationships by trust [14]. Thus, examining the psychological mechanism between life satisfaction and turnover intention through social exchange theory (SET) and resource maintenance model is important and necessary.

Finally, the literature also specifies that high individual turnover intention may cause a range of problems and unfavorable outcomes for both employees and organizations, particularly those relating to the loss of direct as well as indirect cost in human resource management (HRM) practices [15]. The traditional turnover models mostly concentrate on addressing why individuals decide to leave are too narrow to provide a holistic view [16]. However, the organizational embeddedness theory can better explain why people choose to stay with organizations and has been introduced into the discussion of turnover issues in recent years [16]. This theory explicitly highlights the importance of perceptions on the fits and links between their jobs and surrounding working conditions and implicitly details what people would lose if they quit [17]. It offers a comprehensive hypothetical structure that incorporates individual insights with the community and organizational traits to elucidate the aspects confining workers to an explicit atmosphere [18]. We, consequently, contend that organizational embeddedness seems to be appropriate for expounding the workers’ life satisfaction-trusted climate in our study contextual, as the uniqueness of the working settings inherent in Muslim values can be presented. So, this study integrates the perceptions of organizational embeddedness and workers’ related climate to explore the mechanisms between life satisfaction —turnover intention in a developing country, Pakistan in this pandemic situation.

2Theoretical background and hypothesis development

2.1Life satisfaction and turnover intention

Better life necessarily entails well-being. In the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers’ thoughts and feelings about their own lives and surroundings can be adversely affected by the process [9]. Healthcare workers are worried about losing their jobs. From the adverse situation perspectives, previous literature reported that only psychological wellbeing serves as an umbrella term for happiness, thriving, healthy and optimal functioning at both the national as well as individual levels in both negative and positive circumstances [19]. Given the importance of psychological well-being, life satisfaction is a multi-dimensional construct reflecting the individuals’ overall self-assessed appraisals of the quality of life [20]. As a general construct, different terms are used to describe the satisfaction of one’s life, such as “life adjustment, “quality of life, “joy, “happiness, “morale,” and “life satisfaction.” But, ultimately, all are related to a person’s overall happiness and satisfaction in his/her life. Herein, life satisfaction is not just essential for the employees but also their employers. As a similar concept has also been reported by Mobley [21], non-working variables should be investigated as powerful predictors of turnover intention. Different other scholars [22–24] found that life satisfaction is linked with PA (positive affect) and NA (negative affect). For example, people who had satisfied with their lives tend to experience more PA (positive affect) and lower NA (negative affect), while, people who have dissatisfied with their lives tend to experience lower PA and more NA, in turn, we assume that may be its affect turnover intention. According to the resource maintenance model [25] which clarifies that the majority of individuals believe happiness is highly valuable and also stated to maintain it whenever possible. In this pandemic context, the conservation of resource theory states, a continuous shortfall in valued resources ultimately causes burnout behavior [26]. Moving further, Wright and Bonett [27] suggested reawakening the traditional research by scrutinizing the relationship between life satisfaction turnover intention phenomenon. Hence, when worker happiness is low in this pandemic situation, workers might be encouraged to develop their resources and try to actively manage them. So, all the above discussions lead to the following hypothesis:

H1: Life satisfaction will be negatively associated with turnover intention.

2.2Mediating role of trust

Recent evidence from Hu [28] reveals that create a trusted climate in hospitals increases the willingness of healthcare workers to work during the pandemic situation. Within the hospital context, there is a strong need to create trust between workers and employers by providing optimum resources to frontline workers [29]. Trust is defined as “it is a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another” [30]. The extant research has suggested that trust is a remarkable aspect in generating good human relationships and social interactions [31] as well as become helpful in providing an environment in which they feel secure [32]. Another aspect from the same literature highlighted that trust might foster collaboration between persons, help to uphold close connections between individuals, and which lead to improving workers’ subjective well-being [28, 33, 34]. Moreover, trust has a significant predictor of different job outcomes, for example, commitment, satisfaction, and turnover intentions [35].

It is clear from the recent literature that the relationship exists between employee well-being and trust climate [13] and adverse situation (i.e., turnover intention). As SET [36] further provides the basic understanding of worker attitude by focusing on trust. Drawing on SET, this study endeavors to scrutinize the controversial understanding of the virtue of well-being literature. SET is explicated the importance of general exchange or favorable action “initiated by an organization’s treatment of its workers, with the expectation that such treatment will be eventually reciprocated” [37]. Concisely, individuals who feel satisfied or happy to reciprocate by exhibiting an additional positive behavior at work for the reason that when they are receiving favorable climate and necessary benefits; on the other hand, they also review their job attitudes negatively in reaction to unfavorable conduct [38]. So, trust increases or decreased through reciprocal exchange between persons. Following the logic of SET, we expect that individuals with higher levels of life satisfaction are expected to have a positively associated with norms of reciprocity and trust [39], which is an important predictor of turnover intention [35] in this pandemic situation. Thus, we follow:

H2: Trusted climate will mediate the association between life satisfaction and turnover intention.

2.3Moderating role of job embeddedness

In the context of COVID-19, Mancini and Policy [40] reported that “we must remain vigilant to the potential harms, but we should not lose sight of the ways the pandemic may positively impact social and psychological functioning” (p. S16). In this vein, Lau and Yang [41] stated that during the Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong in 2003, people are reported highly embedded in their settings. From this angle, we propose that job embeddedness also plays an important role in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Job embeddedness can be defined as the collective forces that keep an individual from leaving his or her job [42]. Whereas, job embeddedness theory argues that how employee perception fit with their environment, understanding links to those around them, as well as what they would lose if they quit [16]. Evidence suggests that job embeddedness provides a sound theoretical structure to explicate why employees stay with the organization and integrating the perceptual, social, and organizational aspects that decrease employee retention [43]. As job embeddedness is conducive to employee turnover intention [44], and in a meta-analysis was specifically called moderator to play a significant role in turnover intention study [45]. Further following, the perspective of the interaction that based on the ongoing multidirectional practices of the individual by situational interactions [46], from this perspective we expect that job embeddedness is also different based on the individual interactions that moderates the association between life satisfaction and trust climate in the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the next hypothesis as follows:

H3: Job embeddedness moderates the association between life satisfaction and trusted climate, such that this association is stronger when job embeddedness is higher.

In addition, based on the associations anticipated in Hypotheses 2 and 3, we propose that the mediated association between life satisfaction and turnover intention through trusted climate will be contingent on job embeddedness [47]. Thus, the next hypothesis is as follows:

H4: The indirect association between life satisfaction through trusted climate is moderated by job embeddedness, such association is stronger when job embeddedness is higher.

3Meterial and methodos

3.1Sample and procedure

Data for the current research were collected from public healthcare workers working in seven different private-public hospitals located in Pakistan. We selected public healthcare workers who deployed in special COVID-19 emergency wards in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The questioners were distributed with the help of the Human Resource Departments of these hospitals. Participants completed the questionnaire anonymously and returned it to the Human Resource Department on their own time. To minimize the presence of response distortion [48], respondents assured the confidentiality of their responses.

A total of 520 public healthcare workers completed the survey questionnaire. Of 550 workers’ questionnaires distributed, 520 responses were collected successfully, resulting in a response ratio of 94 percent. In this sample, 274 participants (52.70 percent) were from the frontline nurses, and the remaining 246 (47.30 percent) were from the emergency medical personnel. Male and females made up approximately 55 and 45 percent of the sample, respectively. Finally, the average tenure in the organization was five years (range from four months to 18 years).

3.2Ethical consideration

The study was conducted through the proper channel by getting approval from the University Ethical Committee (reference # 2021-01-04/05). All the participants were giving them informed before the start of the questionnaire. The names of the participants were coded (e.g. CP1, CP2) and kept confidential.

3.3Measures

Responses to the four scales included to assess life satisfaction, job embeddedness, trust, and turnover intention were measured using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree).

3.3.1Life satisfaction

The construct was measured by five items of a scale developed by Diener, Emmons [49]. This scale was widely used for cognitive state measure encompasses a general assessment of one’s life. Sample items include “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life,” “The conditions of life are excellent,” and “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal”. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.86.

3.3.2Job embeddedness

The construct was measured by seven items of a scale developed by Crossley, Bennett [50]. Example items include “It would be difficult for me to leave this organization,” “I am too caught up in this organization to leave,” and “I am tightly connected to this organization”. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.93.

3.3.3Trust

This construct has been measured with the scale developed by Donovan, Drasgow [51]. Two of the fourteen items are “Workers are treated fairly,” and “Workers complaints are deal with effectively”. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.95.

3.3.4Turnover intention

The turnover intention has been measured with a scale developed by Crossley, Grauer [52]. Two of the five items Sample items are “I plan to leave the organization in the next little while,” and “I may leave this organization before too long”. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.90.

3.3.5Control variable.

Demographic variables are mostly included as control variables in the turnover intention model [5]. Thus, we included the following three variables representing gender, marital status, and department of workers as control variables for the analysis.

4Results

4.1Confirmatory factor analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS on our proposed four-factor model (job embeddedness, turnover intention, life satisfaction, trust) to test the construct validity. We first examined our four-factor baseline model (Model 1). To assess the model’s goodness-of-fit χ2, CFI, RMSEA, and TLI indices were applied. Further, we compared the four alternative or nested models (model 2–5) to the baseline four factors (Model 1). Whenever we compared the alternative model with the baseline model, we used χ 2 difference tests that guide us to which model is the best fit to the data suggested by Anderson and Gerbing [53].

Table 1 presents the CFA results of the proposed model. As shown in Table 1, the all the alternative models’ results showed significantly poorer fit than the four-factor baseline model, as to confirm from significant χ2 difference tests. The baseline model showed best fit the data (χ2 = 1031.03, df = 428, RMSEA = 0.05, IFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, CFI = 0.94). Hence, these results suggest adequate construct validity between the study variables.

Table 1

Comparisons of measurement models

| Model # | Total factors | χ2 | df | Δχ2 | Δχ2 | TLI | IFI | RMSEA | CFI |

| Model 1 | Four-factor target model | 1031.03*** | 428 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 0.94 | ||

| Model 2 | Three-factor model A | 1786.16*** | 431 | 755.13 | 755.13 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.09 | 0.85 |

| Model 3 | Three-factor model B | 2993.29*** | 431 | 1207.13 | 1207.13 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.72 |

| Model 4 | Two-factor model | 3641.08*** | 433 | 647.79 | 647.79 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.13 | 0.66 |

| Model 5 | One-factor model | 4430.79*** | 434 | 789.71 | 789.71 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.14 | 0.57 |

Note. N = 520*** p < 0.001, Cronbach alpha reliabilities for observed variables are in the diagonal

4.2Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics means standard deviations, alpha reliabilities, and correlations for the study variables are shown in Table 2. Bivariate correlation shows that life satisfaction was positively associated with trust climate (r = 0.39, p < .01) and turnover intention (r = –0.28, p < .01). Likewise, trust climate was negatively associated with turnover intention (r = –0.54, p < .01). These results provide preliminary support for the proposed moderated mediation hypothesis.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics and bivariate among the study variables

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1. Life satisfaction | 3.59 | 1.22 | (0.86) | |||||

| 2. Trust | 3.71 | 1.07 | 0.39** | (0.95) | ||||

| 3. Job embeddedness | 3.84 | 0.95 | 0.32** | 0.31** | (0.93) | |||

| 4. Turnover intention | 2.65 | 0.99 | –0.28** | –0.54** | –0.26** | (0.90) | ||

| 5. Gender | 0.55 | 0.49 | –0.05 | –0.08 | –0.05 | –0.02 | ||

| 6. Marital status | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.09 | 0.11* | –0.03 | –0.15** | –0.07 | |

| 7. Department | 0.47 | 0.50 | –0.06 | –0.03 | –0.05 | 0.04 | –0.08 | 0.07 |

Note: N = 520, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

4.3Hypotheses testing

For testing the hypotheses, we conducted a series of multiple regression analyses by putting the control variables and study variables in different steps. To test the hypotheses (1–2), we entered control variables into the model in the first step, next by the predictor variable of life satisfaction in step 2, and lastly, the mediator (trust climate) was entered into the model to examine the mediation impact. As displayed in Table 3, life satisfaction had a negative impact on workers’ turnover intention (β= –0.22, p < .001). Hence, these results support hypothesis 1.

Table 3

Hirarchical regression analysis results

| Turnover intention | Trust | ||||||

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 | Step 6 | Step 7 | |

| Control effect | |||||||

| Marital status | –0.33** | –0.28** | –0.19 | 0.27* | 0.19 | 0.22* | 0.18 |

| Gender | –0.04 | –0.07 | –0.13 | –0.17 | –0.13 | –0.11 | –0.14 |

| Department | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.05 | –0.10 | –0.04 | –0.02 | –0.05 |

| Main effect | |||||||

| Life satisfaction | –0.22*** | –0.06 | 0.34*** | 0.28*** | 0.27*** | ||

| Mediating effect | |||||||

| Trust | –0.47*** | ||||||

| Moderating effect | |||||||

| Job embeddedness | 0.24*** | 0.33*** | |||||

| Interactions effect | |||||||

| Life satisfaction×job embeddedness | 0.19*** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

| ΔR2 | –0.03* | 0.07*** | 0.22*** | 0.02* | 0.15*** | 0.04*** | 0.50*** |

| F | 3.41* | 10.97*** | 37.49*** | 3.36* | 20.66*** | 21.66*** | 23.81*** |

Note: N = 520; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Fig. 1

A proposed moderated mediation model.

To predict hypothesis 2, we followed [54] suggestion for testing and reporting mediation. As can been seen Table 3, life satisfaction was positively related to trust climate (β= 0.34, p < .001). Furthermore, the relationship between life satisfaction and workers’ turnover intention became insignificant significant when the trust enters into the model (β= –0.06, ns), whereas trust climate was found to be negatively associated with workers’ turnover intention (β= –0.47, p < .001). Hence, our prediction of the mediation was found full support for hypothesis 2.

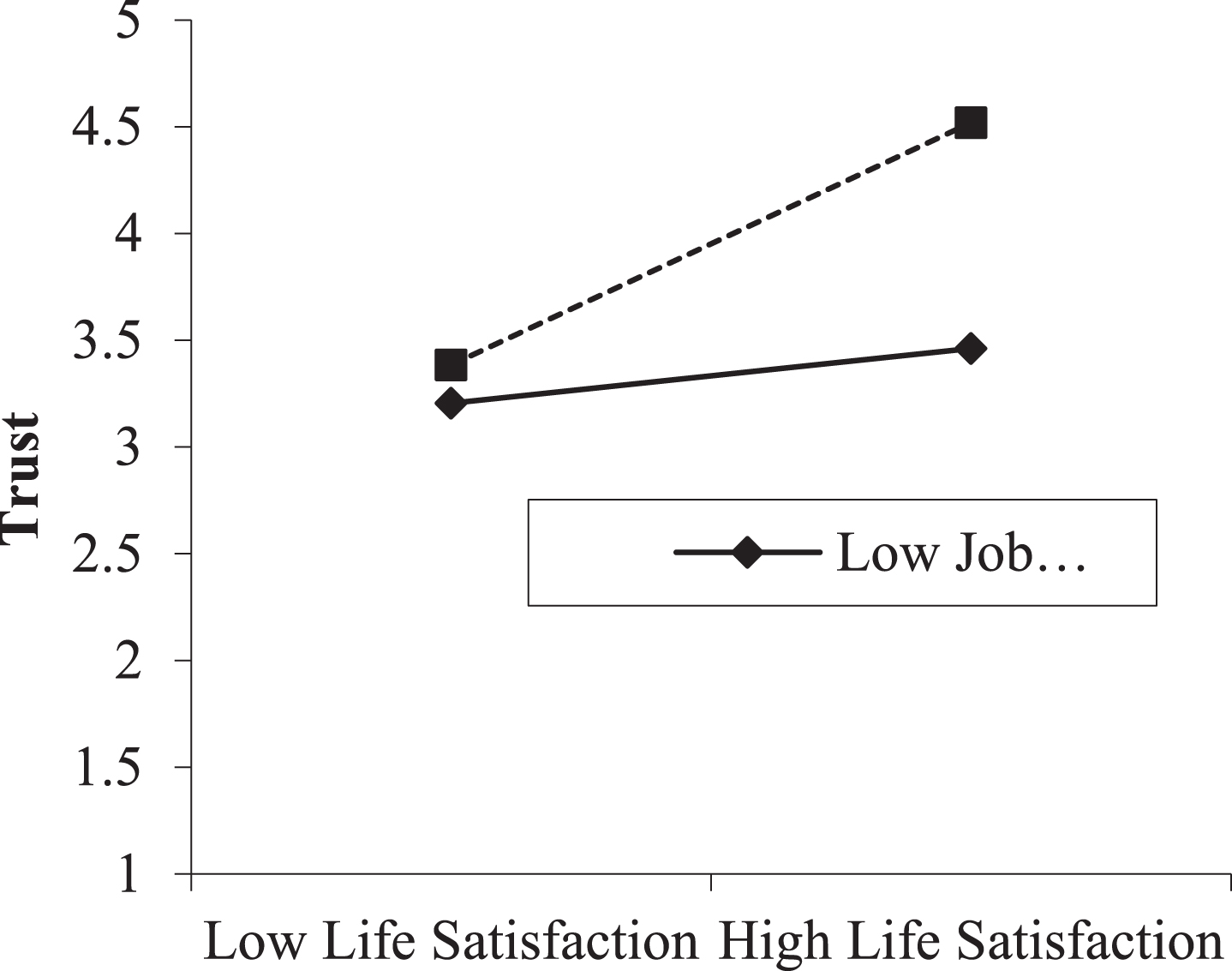

Hypothesis 3 predicted that job embeddedness moderates the association between life satisfaction and trust climate. We centered life satisfaction, job embeddedness to reduce multicollinearity often associated with their interaction terms [55]. The job embeddedness×life satisfaction interaction term was significant for workers related to trust climate (β= 0.19, p < .001).

As shown in Fig. 2, the nature of the significant interaction was scrutinized by plotting scores with one SD below and above the mean from the moderator [55]. Figure 2 reveals that the association between life satisfaction and workers’ trust climate was more positive and significant when job embeddedness level was high (β= 0.52, p < .001) and also significant when job embeddedness level was low (β= 0.12, p < .001). Thus, these results support hypothesis 3.

Fig. 2

Moderating role of job embeddedness between life satisfaction and trust climate.

Hypothesis 4, anticipated that the job embeddedness moderates the mediating linkage of life satisfaction-workers’ turnover. We used the moderated-mediation analytical method to examine this hypothesis that was suggested by Edwards and Lambert [47]. This method scrutinizes the mediator and moderator simultaneously in a path analytic outline, that is the first stage moderated mediation model which infers all three stages of the mediation process can be adjusted by the moderators.

We employed constrained nonlinear regression (CNLR) to estimate the coefficients from 1,000 bootstrap samples. Next, we put these estimated coefficients into the Microsoft Excel file (i.e., syntax) developed by Edwards and Lambert [47] to compute all effects and paths (i.e., direct, indirect, total), and also compute the differences between each effect and path across 1 SD above and below the mean from the moderator variable.

The results in Table 4 exposed that the indirect relationship between life satisfaction and turnover intention via trust climate was significant for both high and low job embeddedness (β= –0.23, p < .01; β= –0.02, p < .01). However, the conditional indirect relationship between high and low was significantly different (Δ β= –0.21, p < .01). Hence, these results support hypothesis 4. Furthermore, first-stage moderation result (Δ β= 0.36, p < .01), proposing that life satisfaction interacts with job embeddedness to predict workers’ trusted climate, which, in turn, affects worker turnover intention. Thus, these results receive further support for hypothesis 4.

Table 4

Analysis of simple effects

| Life satisfaction (X) ⟶ Trust climate (M) ⟶ Turnover intention (Y) | ||||

| First stage | Second stage | Direct effect | Indirect effect | |

| Variable | PMX | PYM | PYX | PMX×PYM |

| Trust climate | ||||

| Low trust climate (–1SD) | 0.10** | –0.19** | 0.25** | –0.02** |

| High trust climate (+1SD) | 0.46** | –0.51** | –0.39** | –0.23** |

| Difference | 0.36** | –0.32** | –0.64** | –0.21** |

Note: **p < 0.01; PMX = path from life satisfaction to trust climate; PYM = path from trust climate to turnover intention; PYX = path from life satisfaction to turnover intention.

5Discussion

This study examined the effect of life satisfaction on workers’ turnover intention via data gathered from healthcare workers in Pakistan. In particular, we explored the mediating role of trusted climate on workers’ life satisfaction and turnover intention phenomenon and the moderating role of job embeddedness in influencing the median. Further, we find that this research contributes to the life satisfaction and turnover intention literature in several ways.

The results emerging from this research would give a better understanding to healthcare executives on how to increase workers’ life satisfaction and decrease turnover intention via trusted climate and job embeddedness among the healthcare workers. The key findings of this research are discussed as follows.

First, previous literature suggested that workers’ well-being has been disputed in the literature [13], paid scant attention to workers’ well-being conception as compared to other satisfaction [12]. In respect to the prior body of research found that trust has an important predictor to successful negotiations and conflict management efforts [56], and it has a control influence on disputants’ reactions to settle these disputes as a mediator [57].

According to our knowledge, this study evinces the first in-depth investigation of the relationship between life satisfaction and turnover intention in the COVID-19 pandemic. So, this study contributes to the literature by providing back for the efficaciousness of life satisfaction at the workers’ general level. The findings of this study showed that due to the fear of COVID-19 healthcare workers have shown a lower level of satisfaction in their and higher level of turnover intention. This turnover intention is higher because of the fear of COVID-19 which may interfere with employees’ productivity and leading to the lower level of satisfaction in their life as well. This finding is supported by previous work [3], where employees feel highly distressed and insecure in adverse working situations.

Next, consistent with our assumed model, as per our results, trust climate indeed plays a key role as a mediator influencing the associations of life satisfaction and turnover intention. Specifically, we explore the climate in which workers interact with their colleagues and advocate that life satisfaction will lead to a climate that workers perceive as high in trust. Employing SET [36] as the theoretical context, we found that creating a trust-related environment in organizations will provide a mechanism through which workers satisfied from life can contribute to deterring a turnover intention in healthcare workers.

A key challenge faced by organizations is that how they can create environments where workers feel secure and experience trust [58]. For example, organizations that do not form a trust-related attitude with workers basically, create a foundation for burnout [59, 60]. We recommend that the relationship between life satisfaction and trust climate will be elevated in the existence of a higher level of workers’ job embeddedness. Because job embeddedness is the concept that guides the workers’ behavior according to the surrounding through the support systems at the workplace, hence embedding the workers into the organization [61]. So, in terms of understanding why job embeddedness is important in the organizational context, our study adds further. Overall here, by addressing the fear of COVID-19, creating a trusted and embedded climate among healthcare workers will be the increase satisfaction in their lives and decreased turnover intention.

This study provides further guidance for hospital management and policymakers in supporting healthcare workers during adverse working situations. For example, hospital management needs to introduce training programs and online webinars to enhance the capacity of healthcare workers to effectively take care of COVID-19 patients and as well as themselves. These awareness-related programs are building a trust-related climate among healthcare workers. Furthermore, when healthcare workers will get support from the organization and colleagues that will ultimately keep them embedded in the workplace. These are the different resources including information, support, and trust in management will enance satisfaction in their lives and keep performing them at a job.

Similar to other studies, this study also suffered from some limitations. Firstly, we used only a single source of data collection, namely self-reported measures. However, in methodological terms, the results might find mono-method bias within investigated variables through high correlations. Different other studies have shown that such kind of bias very few likelihoods against assuming [62]. To reduce such kind of business, future research should be carried out by using multiple sources in organizations. Secondly, the generalizability of our findings may be contaminated by the population’s sample. Because this study was conducted in Pakistan healthcare workers. The findings of this study may be generalized only to the participants included in this study. So, it might be the results of this study with caution as a cultural comparison of healthcare workers’ experience of one country had very from other countries. Hence, future research should be considered workers’ well-being and turnover intention in worldwide contexts. As we know this pandemic situation is not only limited to one country.

6Conclusion

The theory and findings suggest that how life satisfaction and job-embedded interact to build trust-based relationships with their healthcare workers that become helpful in deterring the adverse effect of workers turnover intention. Thus, to create and retain a healthy workforce, organizations must adopt policies that assist them to enhance workers’ well-being in organizations.

Acknowledgment

The first author extends their appreciation to the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan for funding this work through the Startup Research Grant Project (SRGP) under grant number 212/IPFP-II(Batch-I)/SRGP/NAHE/HEC/2020/72.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

[1] | Wadhen V , Cartwright T . Feasibility and outcome of an online streamed yoga intervention on stress and wellbeing of people working from home during COVID-19. Work. (2021) ;69: :331–49. |

[2] | Sharma A , Borah SB , Moses AC . Responses to COVID- The role of governance, healthcare infrastructure, and learning from past pandemics. Journal of Business Research. (2021) ;122: :597–607. |

[3] | Huffman AH , Albritton MD , Matthews RA , Muse LA , Howes SS . Managing furloughs: how furlough policy and perceptions of fairness impact turnover intentions over time. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2021:1-28. |

[4] | Sizemore LM , Peganoff-O’Brien S , Skubik-Peplaski C . Interference: COVID-19 and the Impact on Potential and Performance in Healthcare. Work. (2021) ;69: :767–74. |

[5] | Mobley WH , Griffeth RW , Hand HH , Meglino BM . Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychological Bulletin. (1979) ;86: (3):493–522. |

[6] | Özmen S , Özkan O , Özer Ö , Yanardab MZ . Investigation of COVID-19 Fear, Well-Being and Life Satisfaction inTurkish Society. Social Work in Public Health. (2021) ;36: (2):164–77. |

[7] | Zheng L , Miao M , Gan Y . Perceived Control Buffers the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on General Health and Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Psychological Distance. (2020) ;12: (4):1095–114. |

[8] | Karataş Z , Tagay Ö . The relationships between resilience ofthe adults affected by the covid pandemic in Turkey and Covid-19fear, meaning in life, life satisfaction, intolerance of uncertaintyand hope. Personality and Individual Differences. (2021) ;172: :110592. |

[9] | Zhang SX , Chen J , Afshar Jahanshahi A , Alvarez-Risco A , Dai H , Li J , et al. Succumbing to the COVID-19 Pandemic—Healthcare Workers Not Satisfied and Intend to Leave Their Jobs. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2021. |

[10] | Rode JC , Rehg MT , Near JP , Underhill JR . The Effect of Work/Family Conflict on Intention to Quit: The Mediating Roles of Job and Life Satisfaction. Applied Research in Quality of Life. (2007) ;2: (2):65–82. |

[11] | Ghiselli RF , La Lopa JM , Bai B . Job Satisfaction, Life Satisfaction, and Turnover Intent:Among Food-service Managers. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. (2001) ;42: (2):28–37. |

[12] | Erdogan B , Bauer TN , Truxillo DM , Mansfield LR . Whistle While You Work:A Review of the Life Satisfaction Literature. Journal of Management. (2012) ;38: (4):1038–83. |

[13] | Downey SN , van der Werff L , Thomas KM , Plaut VC . The role of diversity practices and inclusion in promoting trust and employee engagement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. (2015) ;45: (1):35–44. |

[14] | Ertürk A , Vurgun L . Retention of IT professionals: Examining the influence of empowerment, social exchange, and trust. Journal of Business Research. (2015) ;68: (1):34–46. |

[15] | Zhang LL , George E , Chattopadhyay P . Not in My Pay Grade: The Relational Benefit of Pay Grade Dissimilarity. Academy of Management Journal. (2020) ;63: (3):779–801. |

[16] | Rafiq M . The moderating effect of career stage on the relationship between job embeddedness and innovation-related behaviour (IRB) Evidence from China. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development. (2019) ;15: (2):109–22. |

[17] | Peltokorpi V , Allen DG , Froese F . Organizational embeddedness, turnover intentions, and voluntary turnover: The moderating effects of employee demographic characteristics and value orientations. (2015) ;36: (2):292–312. |

[18] | Stoermer S , Davies S , Froese FJ . The influence of expatriate cultural intelligence on organizational embeddedness and knowledge sharing: The moderating effects of host country context. Journal of International Business Studies. (2021) ;52: (3):432–53. |

[19] | Ayhan C , Işık Ö , Kaçay Z . The relationship betweenphysical activity attitude and life satisfaction: A sample ofuniversity students in Turkey. Work. (2021) ;69: :807–13. |

[20] | Rafiq M , Chin T . Three-Way Interaction Effect of Job Insecurity, Job Embeddedness and Career Stage on Life Satisfaction in A Digital Era. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. (2019) ;16: (9):1580. |

[21] | Mobley WH . Employee turnover, causes, consequences, and control: Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, Boston; (1982) . |

[22] | Xiang Y , Yuan R , Zhao J . Childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction in adulthood: The mediating effect of emotional intelligence, positive affect and negative affect. Journal of Health Psychology. 2020:1359105320914381. |

[23] | Busseri MA . Examining the structure of subjective well-being through meta-analysis of the associations among positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences. (2018) ;122: :68–71. |

[24] | Kong F , Gong X , Sajjad S , Yang K , Zhao J . How Is Emotional Intelligence Linked to Life Satisfaction? The Mediating Role of Social Support, Positive Affect and Negative Affect. Journal of Happiness Studies. (2019) ;20: (8):2733–45. |

[25] | Cropanzano R , Wright TA . When a “happy” worker is really a “productive” worker: A review and further refinement of the happy-productive worker thesis. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research. (2001) ;53: (3):182–99. |

[26] | Hobfoll SE . Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American psychologist. (1989) ;44: (3):513–24. |

[27] | Wright TA , Bonett DG . Job Satisfaction and Psychological Well-Being as Nonadditive Predictors of Workplace Turnover. Journal of Management. (2007) ;33: (2):141–60. |

[28] | Hu A . Specific Trust Matters: The Association between the Trustworthiness of Specific Partners and Subjective Wellbeing. The Sociological Quarterly. (2020) ;61: (3):500–22. |

[29] | Kang S-E , Park C , Lee C-K , Lee SJS . The Stress-Induced Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism and Hospitality Workers. (2021) ;13: (3):1327. |

[30] | Rousseau DM , Sitkin SB , Burt RS , Camerer C . Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review. (1998) ;23: (3):393–404. |

[31] | Rafiq M , Weiwei W . Managerial trust outlook in China and Pakistan. Human Systems Management. (2017) ;36: (4):363–8. |

[32] | Fang M , Hasan I , Sharma Z , Yan A . Firm social networks, trust, and security issuances. The European Journal of Finance. 2020:1-36. |

[33] | Leighton JP , Bustos Gómez MC . A pedagogical alliance for trust, wellbeing and the identification of errors for learning and formative assessment. Educational Psychology. (2018) ;38: (3):381–406. |

[34] | Su Y , Zahra SA , Li R , Fan D . Trust, poverty, and subjective wellbeing among Chinese entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development. (2020) ;32: (1-2):221–45. |

[35] | Dirks KT , Ferrin DL . Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology. (2002) ;87: (4):611–28. |

[36] | Blau P . Power and exchange in social life. New York:Wiley & Sons; (1964) . |

[37] | Gould-Williams J , Davies F . Using social exchange theory to predict the effects of hrm practice on employee outcomes. Public Management Review. (2005) ;7: (1):1–24. |

[38] | Wright S , Silard A . Unravelling the antecedents of loneliness in the workplace. Human Relations. 2020: 0018726720906013. |

[39] | Shiau W-L , Luo MM . Factors affecting online group buying intention and satisfaction: A social exchange theory perspective. Computers in Human Behavior. (2012) ;28: (6):2431–44. |

[40] | Mancini ADJPTT, Research, Practice, Policy. Heterogeneous mental health consequences of COVID-19: Costs and benefits. (2020) ;12: (S1):15. |

[41] | Lau JT , Yang X , Tsui H , Pang E , Wing YKJJoI . Positive mental health-related impacts of the SARS epidemic on the general public in Hong Kong and their associations with other negative impacts. (2006) ;53: (2):114–24. |

[42] | Yao X , Lee TW , Mitchell TR , Burton JP , Sablynski CS . Job embeddedness: Current research and future directions. In: Griffeth R, Hom P, editors. Understanding employee retention and turnover: Greenwich, CT: Information Age. 2004;153-87. |

[43] | Rafiq M , Wu W , Chin T , Nasir M . The psychological mechanism linking employee work engagement and turnover intention: A moderated mediation study. Work. (2019) ;62: (4):615–28. |

[44] | Rubenstein AL , Peltokorpi V , Allen DG . Work-home and home-work conflict and voluntary turnover: A conservation of resources explanation for contrasting moderation effects of on- and off-the-job embeddedness. Journal of Vocational Behavior. (2020) ;119: :103413. |

[45] | Jiang K , Liu D , McKay PF , Lee TW , Mitchell TRJJoAP . When and how is job embeddedness predictive of turnover? A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology. (2012) ;97: (5):1077–96. |

[46] | Wu C-H , Parker SK , de Jong JPJ . Need for Cognition as an Antecedent of Individual Innovation Behavior. Journal of Management. (2014) ;40: (6):1511–34. |

[47] | Edwards JR , Lambert LS . Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods. (2007) ;12: (1):1–22. |

[48] | Chan D . Are self-report data really that bad. In: Lance CE, Vandenberg RJ, editors. Statistical and metholodogical myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity and fable in the organizational and social sciences: New York: Routledge. (2009) ;311–38. |

[49] | Diener E , Emmons RA , Larsen RJ , Griffin S . The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. (1985) ;49: (1):71–5. |

[50] | Crossley C , Bennett RJ , Jex SM , Burnfield J . Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. Journal of applied Psychology. (2007) ;92: (4):1031. |

[51] | Donovan MA , Drasgow F , Munson LJ . The Perceptions of Fair Interpersonal Treatment scale: Development and validation of a measure of interpersonal treatment in the workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology. (1998) ;83: (5):683–92. |

[52] | Crossley C , Grauer E , Lin L , Stanton J . Assessing the content validity of intention to quit scales. annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 2002;23-31. |

[53] | Anderson JC , Gerbing DW . Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. (1988) ;103: (3):411–23. |

[54] | Baron RM , Kenny DA . The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality Social Psychology. (1986) ;51: (6):1173–82. |

[55] | Aiken LS , West SG , Reno RR . Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; (1991) . |

[56] | Deutsch M . Trust and suspicion. Journal of Conflict Resolution. (1958) ;2: (4):265–79. |

[57] | Ross WH , Wieland C . Effects of interpersonal trust and time pressure on managerial mediation strategy in a simulated organizational dispute. Journal of Applied Psychology. (1996) ;81: (3):228–48. |

[58] | Bertrand J , Klein P-O , Soula J-L . Liquidity Creation and Trust Environment. Journal of Financial Services Research. 2021. |

[59] | Kalbers LP , Fogarty TJ . Antecedents to Internal Auditor Burnout. Journal of Managerial Issues. (2005) ;17: (1):101–18. |

[60] | Bianchi R , Verkuilen J , Schonfeld IS , Hakanen JJ , Jansson-Fröjmark M , Manzano-García G ,et al. Is Burnout a Depressive Condition? A 14-Sample Meta-Analytic and Bifactor Analytic Study. Clinical Psychological Science. 2021:2167702620979597. |

[61] | Wheeler AR , Harris KJ , Sablynski CJ . How Do Employees Invest Abundant Resources? The Mediating Role of Work Effort in the Job-Embeddedness/Job-Performance Relationship. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. (2012) ;42: (S1):E244–E66. |

[62] | Spector PE . Method Variance in Organizational Research: Truth or Urban Legend? Organizational Research Methods. (2006) ;9: (2):221–32. |