|

Case Series

Management of Covid-19 in the outpatient setting

1 Owner, Empire NY Medical Care, New York, NY, USA

2 Nurse Practitioner, Owner, Empire NY Medical Care, New York, NY, USA

Address correspondence to:

Weymin Hago

MD, 450 Park Ave S Suite 202, New York, NY 10016,

USA

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100087Z06WH2020

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Hago W, Amen M. Management of Covid-19 in the outpatient setting. Case Rep Int 2020;9:100087Z06WH2020.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel virus that is responsible for the current infection known as coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). SARS-CoV-2 was first discovered on December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, and led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare it a public health emergency on January 30, 2020. By reviewing the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 we can better understand the patient’s symptoms in conjunction with imaging findings seen in moderate illness Covid-19 patients. In these case studies we demonstrate the benefit of using acetazolamide for patients with moderate illness.

Case Series: We present two cases of Covid-19 patients exhibiting moderate illness. Both patients received antibiotics in the first two weeks of illness with improvement of dry cough and fever; however, they subsequently developed shortness of breath. The imaging findings of both patients revealed infiltrates of the lower lobes. The patients were treated with acetazolamide leading to clinical improvement.

Conclusion: Moderate illness Covid-19 patients who present with pulmonary edema can benefit from the use of acetazolamide from the effects of diuresis and changes in pH.

Keywords: Acetazolamide, Covid-19, SARS-CoV-2 treatment

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a respiratory infection caused by coronavirus that leads to symptoms of fever and cough that can ultimately progress to respiratory failure. SARS-CoV-2 was first discovered on December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, and led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare it a public health emergency on January 30, 2020 [1]. At the beginning of the pandemic, we had no known guidelines to manage patients with Covid-19. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) recently released guidelines to define illness severity and some recommendations for management. Unfortunately, there is limited data for the management of moderate illness Covid-19 patients that can lead to the progression of severe disease. Moderate illness is defined as patients with evidence of lower respiratory disease by clinical assessment or imaging with ≥94% oxygen saturation on room air [2]. By reviewing the current proposed pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2, we can surmise that the damage to the alveolar cells leads to fluid accumulation in the lung. This pulmonary edema should respond to diuretics; however, it is not a considered treatment option for this patient population. In our case studies, we chose the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, acetazolamide, for its diuretic effect and its unique effect on pH. We present two Covid-19 patients who despite an initial course of antibiotics progressed to moderate illness and subsequently treated with acetazolamide led to clinical improvement.

CASE SERIES

Case 1

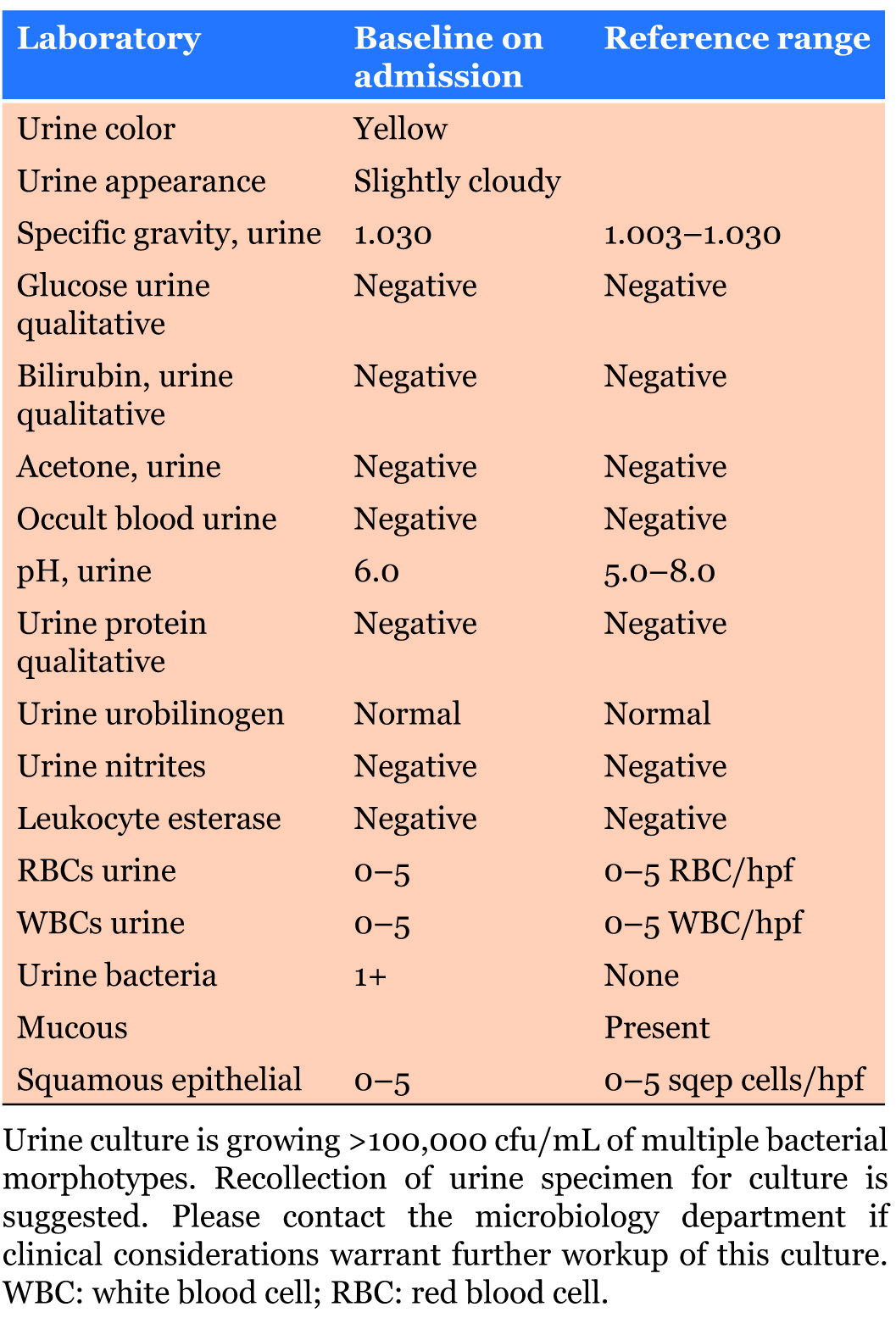

A 47-year-old man with hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity presented via telemedicine with complaints of worsening dyspnea on exertion and dry cough for two weeks. Prior to presentation, the patient tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and initial treatment regimen included, albuterol inhaler two puffs every 6 hours as needed and a course of oral azithromycin 500 mg by mouth (PO) on day 1, then 250 mg for four more days. While constitutional symptoms of fever, malaise, dry cough, body aches improved; he started to develop dyspnea. He was subsequently evaluated at urgent care. Repeat SARS-CoV-2 PCR remained positive. Chest imaging revealed focal patchy infiltrates in the lingula, left lower lobe, and medial right lower lobe. A second course of azithromycin was recommended. The patient contacted his primary care provider (PCP) via telemedicine for a second opinion. During consultation the patient was advised to discontinue antibiotics and acetazolamide therapy was initiated. Dosing began with acetazolamide 125 mg PO daily with subsequent titration to 250 mg PO twice a day (BID) to achieve subjective diuresis. After five days of treatment, the patient reported marked improvement in symptoms including the ability to scale three flights of stairs—prior to treatment he was unable to escalate one flight without stopping. Repeat chest X-ray after treatment revealed persistent but improved bilateral pulmonary infiltrates.

Case 2

A 37-year-old woman with hypothyroidism consulted via telemedicine with complaints of persistent dry cough, low grade fevers, shortness of breath and chest tightness. Approximately two weeks prior to consult, the patient had low grade fevers, dry cough and malaise. The patient tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 via PCR and was given azithromycin PO 500 mg on day 1, and 250 mg for four more days. Her symptoms of dry cough and malaise improved; however, she developed chest tightness, shortness of breath, and continued to have low grade fevers. Chest X-ray was performed and revealed a subtle infiltrate in the left lower lobe and prescribed ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO BID for four days and prednisone 30 mg PO BID for two days. However due to side effects the patient was unable to complete the course of antibiotics and contacted PCP due to persistent symptoms. Acetazolamide was initiated at 125 mg PO BID and after 48 hours the medication was discontinued due to development of paresthesias of the face and arms. Despite only two days of acetazolamide the patient noticed marked improvement of her chest tightness and shortness of breath, although persistent low grade fevers continued for one additional week. Follow-up chest imaging demonstrated complete resolution of infiltrate.

DISCUSSION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a respiratory infection that causes a wide range of illness severity from patient to patient. By reviewing the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2, the clinical manifestations and imaging findings seen in moderate illness Covid-19 are better understood.

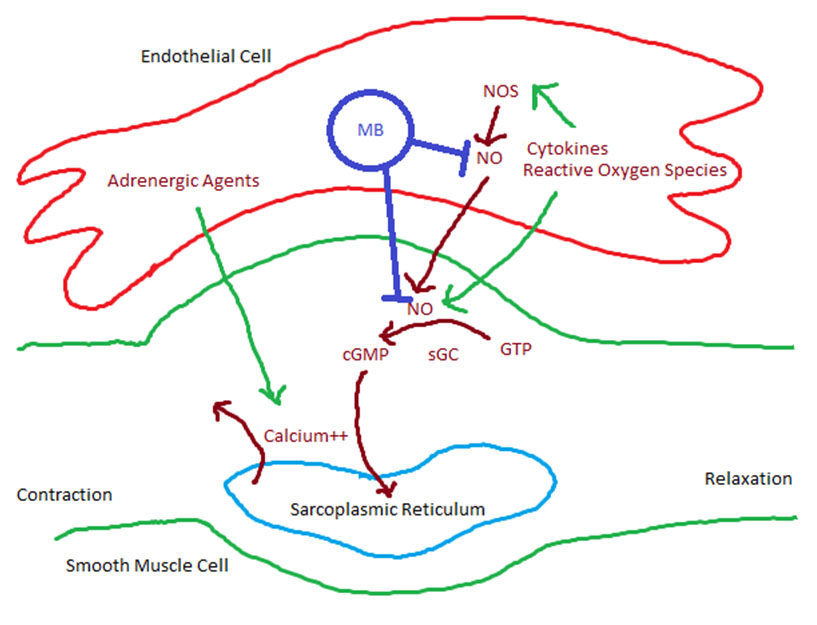

In a recent study of SARS-CoV-2, the structure, function, and antigenicity of the spike (S) glycoprotein was demonstrated [3]. In this study, the S glycoprotein was shown to utilize Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor to gain entry into its target host cells. The effectiveness of this interaction is due to the high affinity for ACE2, furin cleavage of the S protein, and the conformational changes that SARS-CoV-2 undergoes increasing its pathogenicity from human to human [3]. The symptom variability occurring in Covid-19 patients can be explained by localizing ACE2 receptors. With the use of immunostaining of tissues, it was found that ACE2 was expressed on multiple organs including lungs, gastrointestinal, renal, skin, and cardiovascular tissue [4]. The study noted marked staining of ACE2 in type I and type II alveolar epithelial cells (AE1, AE2) and more pronounced in AE2.

By identifying AE2 as the predominant host cell, clinical and imaging changes seen in moderate illness Covid-19 are better understood. Type II alveolar epithelial cells are responsible for surfactant secretion, alveolar fluid balance, epithelial repair, host defense, coagulation-fibrinolysis, and several other functions [5]. It is important to note that the synthesis and secretion of surfactant provides low surface tension which prevents formation of alveolar edema [5]. The loss of surfactant from the damaged AE2 will lead to fluid accumulation in the alveoli which can appear as an infiltrate or opacity on chest imaging. In a recent study from Germany, 9 of 12 Covid-19 patients who died demonstrated infiltrates with ground glass opacities on chest X-ray. The autopsies of these patients revealed diffuse alveolar damage with intra-alveolar edema, hyaline formation, and lymphocyte-plasmocytic infiltration [6]. As we learn more about the functional changes that occur with SARS-CoV-2 we can conclude that the imaging changes in moderate illness patients are related to pulmonary edema. At present there are no approved drugs for treatment of Covid-19; however, we are knowledgeable in managing pulmonary edema regardless of the underlying cause. By not managing the pulmonary edema in these patients they may progress to severe disease from the dysregulation of alveolar fluid. Therefore, it makes sense to diurese these patients for further improvement of symptoms.

Of the potential options to manage pulmonary edema, we found that the mechanism of action of the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (CAI), acetazolamide, can be beneficial due its diuretic effect and its unique acid-base changes. Carbonic anhydrase (CA) is a zinc containing metalloenzyme that is responsible for catalyzing the reversible reaction of carbon dioxide and water into bicarbonate and hydrogen ions [7]. This enzyme can be found in multiple cells throughout the body like the kidney, eyes, stomach, and interestingly AE2 [8]. Acetazolamide facilitates diuresis by inhibiting the reabsorption of bicarbonate in the proximal convoluted tubule leading to the loss of sodium, potassium, and water. The resultant metabolic acidosis from the loss of bicarbonate leads to a stimulation of peripheral and central chemoreceptors which in turn causes a compensatory hyperventilation and improvement in oxygenation [9]. In addition, acetazolamide can create an anti-viral environment by increasing the pH in the alveolar epithelial cells by the loss of CO2. This compensatory respiratory alkalosis can potentially inhibit SARS-CoV-2 viral attachment and replication. Similarly chloroquine has been shown to have anti-viral properties by inhibiting the pH- dependent steps of replication in several viruses [10]. By understanding the function and side effect profile of acetazolamide, we determined that the most suitable patients were those who met criteria for moderate illness Covid-19. As per NIH, moderate illness patients are those who have evidence of lower respiratory disease by clinical assessment or imaging with ≥94% oxygen saturation on room air. Patients who met criteria were started on acetazolamide 125 mg PO BID for five days. The dose of acetazolamide was titrated based on subjective diuresis and whether side effects developed. The patients in this study were evaluated using audio, video connectivity and were followed up closely to monitor blood pressure and symptoms.

CONCLUSION

It is important to acknowledge that in moderate illness Covid-19 there is pulmonary edema. By treating the pulmonary edema associated with Covid-19 with acetazolamide, we can prevent sequelae of inflammation, secondary infection, and hypercoagulability from this fluid stasis. Limitations of isolated case reports are well recognized and additional studies are necessary. Clinical trials are warranted to evaluate the effectiveness of this treatment and the start of in vitro testing to assess the anti-viral effects of acetazolamide against the SARS-CoV- 2 virus.

REFERENCE

1.

Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020;367(6483):1260–3. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Covid-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. 2020. [Available at: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov]

3.

Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 2020;181(2):281–92.e6.

[Pubmed]

4.

Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, Lely AT, Navis GJ, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol 2004;203(2):631–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Fehrenbach H. Alveolar epithelial type II cell: Defender of the alveolus revisited. Respir Res 2001;2(1):33–46. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Schaller T, Hirschbühl K, Burkhardt K, et al. Postmortem examination of patients with COVID-19. JAMA 2020;323(24):2518–20. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Lindskog S. Structure and mechanism of carbonic anhydrase. Pharmacol Ther 1997;74(1):1–20. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Fleming RE, Moxley MA, Waheed A, Crouch EC, Sly WS, Longmore WJ. Carbonic anhydrase II expression in rat type II pneumocytes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1994;10(5):499–505. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Swenson ER. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and ventilation: A complex interplay of stimulation and suppression. Eur Respir J 1998;12(6):1242–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Savarino A, Boelaert JR, Cassone A, Majori G, Cauda R. Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: An old drug against today’s diseases? Lancet Infect Dis 2003;3(11):722–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Acknowledgement

Chris Palmero, MD, Fernando Soto Avellanet, MD

Author ContributionsWeymin Hago - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Meulan Amen - Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2020 Weymin Hago et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.