Supply Chain Disruptions During the COVID-19 Recession

The COVID-19 recession and recovery were characterized by a shift in the composition of consumption away from services and toward durable goods. Lockdowns and social distancing measures, as well as work from home, decreased demand for services. At the same time, fiscal stimulus packages and money saved that could have been spent on services led to higher consumption of durable goods.

Production of durable goods relies on complex global value chains (GVCs), where several stages in the production process are outsourced. While GVCs allow firms to benefit from specialization, there are risks, as firms are exposed to both domestic and foreign shocks. The unprecedented events of the COVID-19 recession, with a global health crisis that led governments around the world to implement containment policies, put pressure on supply chains and shipping networks—at that same time demand for these goods increased rapidly.1

Supply disruptions, combined with a shift in demand toward durable goods, resulted in supply and demand mismatches and bottlenecks. In this essay, we document the unprecedented nature of these supply and demand mismatches.

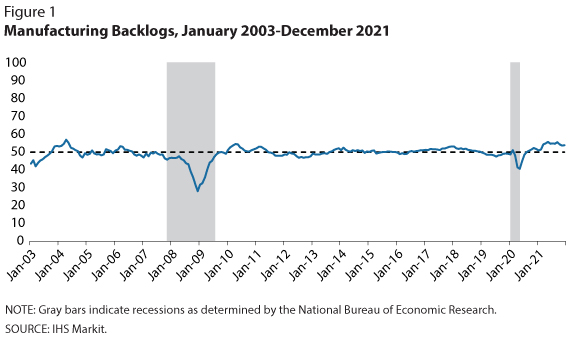

Figure 1 plots data from IHS Markit on world manufacturing backlogs between January 2003 and December 2021. Backlogs measure monthly changes in the number of unfulfilled new orders. The index values are relative to the previous month: 50 represents no change, values below 50 indicate bottlenecks have loosened (i.e., there are fewer unfilled orders and unused production capacity), and values above 50 indicate bottlenecks have tightened (i.e., there are more unfulfilled orders).2 Compared with the COVID-19 recession, the Great Recession was characterized by much looser supply chains initially, with the loosening lasting much longer; as the recovery started, the tightening was mild and short-lived. During the COVID-19 recession, however, bottleneck loosening bottomed out three months after the business cycle peak, and there was a consistent and rapid tightening of backlogs. To the extent that bottlenecks capture both supply and demand factors, Figure 1 shows that (i) mismatches between the two lead to loosening during recessions and tightening during expansions and (ii) there are stark differences between the past two recessions.

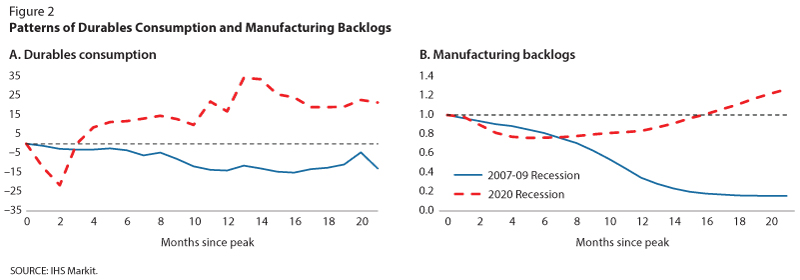

To explore further the role of demand and supply forces during those recessions, Figure 2 compares the evolution of durables consumption (Panel A) and backlogs (Panel B) during the 21 months following the business cycle peak before the Great Recession (January 2008-September 2009) and during the 21 months following the peak before the COVID-19 recession (March 2020-November 2021), respectively.

The Great Recession was characterized by a slow decline and a subsequent slow recovery of durables consumption (Panel A), which 21 months later was still 13% lower than the pre-recession peak. While this is common behavior of durables demand during a typical recession, consumption during the COVID-19 recession and recovery behaved very differently.3,4 Consumption decreased sharply during the first months of the recession but fully recovered three months after the peak, reaching 34% higher 13 months after the business cycle peak (and 21.5% higher 21 months after the business cycle peak).

The rapid increase in durables consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic put pressure on supply, which was already suffering from global lockdowns and a health crisis. In Panel B of Figure 2, we use the data plotted in Figure 1, but instead compute the cumulative growth rate of the backlogs data from Figure 1, normalized to 1 at the peak of each business cycle. A decline (increase) now reflects loosening (tightening) of bottlenecks. Compared with the Great Recession, the COVID-19 recession and recovery was characterized by a steeper loosening of bottlenecks during the first months. However, they began tightening significantly by August 2020, just six months after the peak. By November 2021, backlogs were 27% tighter than at the business cycle peak.

Demand and supply chain disruptions during the COVID-19 recession behaved very differently from those during the Great Recession. While it is difficult to disentangle how much was driven by demand versus supply forces, changes in consumption patterns combined with supply disruptions driven by the global nature of the pandemic led to unprecedented bottlenecks. Supply chain disruptions have been contributing to inflation. Whether this inflation will be temporary or permanent depends on how quickly supply disruptions ease to meet demand. New variants of the virus and new policies enacted to confront those variants make the outlook uncertain.5

Notes

1 Santacreu, Ana Maria; Leibovici, Fernando and LaBelle, Jesse. "Global Value Chains and U.S. Economic Activity During COVID-19." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Third Quarter 2021, 103(3), pp. 271-88; https://doi.org/10.20955/r.103.271-88.

2 A value going from 42 to 47, for example, means that backlogs are still increasing, but at a lower rate than the previous month.

3 Santacreu, Ana Maria and LaBelle, Jesse. "Global Supply Chain Disruptions and Inflation During COVID-19." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 2022 (forthcoming); https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/2022/02/07/global-supply-chain-disruptions-and-inflation-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.

4 Barnes, Mitchell; Bauer, Lauren, and Edelberg, Wendy. "11 Facts on the Economic Recovery from the COVID-19 Pandemic." Hamilton Project Economic Facts, September 2021; https://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/11_facts_on_the_economic_recovery_from_the_covid_19_pandemic.

5 Santacreu and LaBelle (2022, forthcoming).

© 2022, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

follow @stlouisfed

follow @stlouisfed