Steve Watkins

Open access article

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has made this article free to access in order to help healthcare professionals stay informed about an issue of national importance.

To learn more about coronavirus, please visit: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/pharmacy-guides/wuhan-novel-coronavirus

Source: Steve Watkins

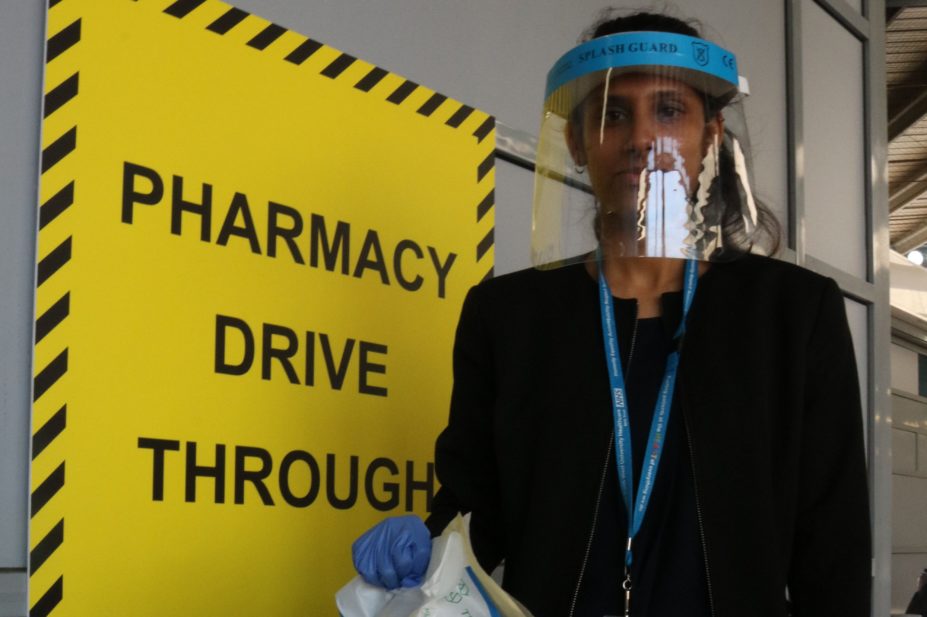

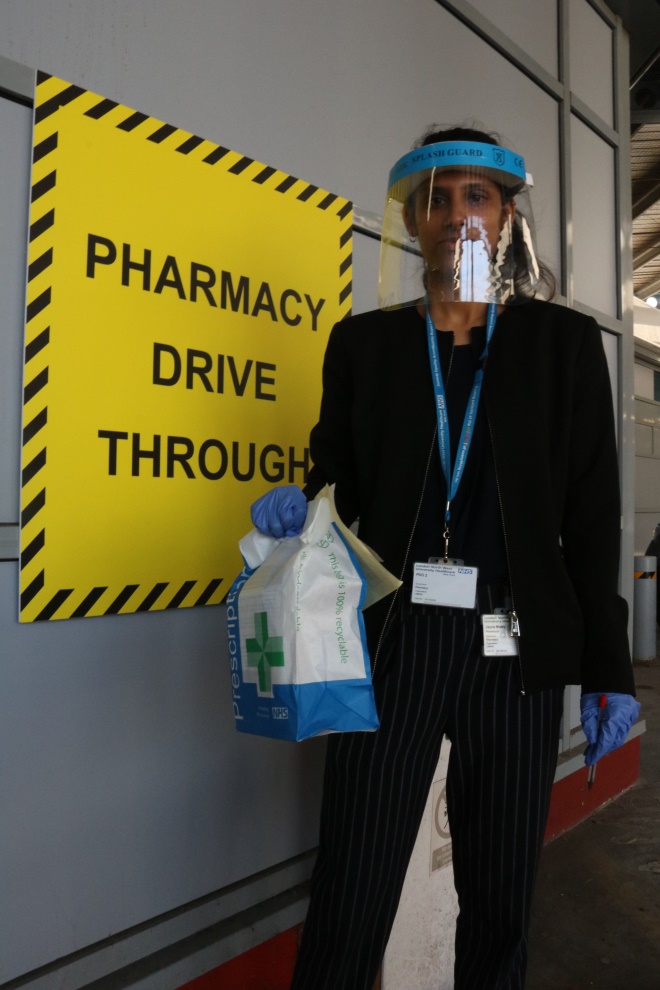

London North West University Healthcare Trust has set up a drive-through pharmacy at Northwick Park Hospital, Harrow, to create a safe medicines collection point during the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the beginning of March 2020, hospital pharmacy teams were faced with drawing up plans to cope with a predicted wave of patients admitted with a new, highly infectious and potentially deadly disease — COVID-19.

Watching the health service become overwhelmed in Italy, pharmacy teams knew that it would not be business as usual, yet there was little information or guidance on how to quickly adapt services. Innovation and redesign that had been considered for years was suddenly adopted in a matter of days or weeks.

Now, four months on, as services begin to return to normal, or at least move to a new phase, pharmacists are starting to consider what changes they may want to keep in the longer term.

1. New medicines preparation and delivery services

There have been a range of new services trialled by pharmacy teams during the pandemic — including aseptic preparation areas and medicines delivery services — that are now being considered for long-term development.

Preparation of ready-to-use injectables to support critical care areas where nursing staff resources are tight has been in the pipeline for a while, says Neil Watson, clinical director of pharmacy and medicines optimisation at The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, who was also involved in setting up NHS Nightingale Hospital North East, one of nine temporary field hospitals constructed across the UK to help the NHS cope during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The Nightingale really forced us down that road because the last thing we wanted was nursing staff spending time making [medicines] up,” he explains. “We are now talking about how to take that forward. [The plan] has always been there, but there’s now momentum behind it.”

Julia Callaghan, deputy chief pharmacist at West Hertfordshire Hospitals NHS Trust, says her team set up a separate aseptic area within the dispensary for preparation of intravenous (IV) medicines, so that nurses would not have to spend time making up IV medicines on the intensive therapy unit (ITU). A standard operating procedure for making up neuromuscular blocking agents is ready to go if needed. “That is in place and we have started to train [people], so if we have a second wave [of COVID-19], we’re ready for that.”

One aspect of care that changed quickly for most hospitals at the start of the pandemic was a fall in outpatient appointments, as services moved to telemedicine. In March and April 2020, 46% of services were delivered virtually compared with just 6% in February and March 2020. That posed an immediate challenge around how to get medicines to patients in a way that did not increase transmission of the virus.

“We quickly set up a delivery system that allowed us to get medicines to shielding or self-isolating patients,” says Watson. The team is now thinking of ways to develop the service. “If anything, we’re going to expand delivery,” he adds.

The ‘drive through’ provides a patient-centred service with the opportunity to consult and support medicines optimisation in a safe and convenient environment

Christine Ward, chief pharmacist at London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust, set up a drive-through medicines collection point in addition to a courier service for outpatients. “We have a big cohort of patients on immunosuppressants and when the pandemic started in early March, we were one of the first hospitals to see a huge number of COVID-positive patients,” she explains. “We wanted to minimise the risk for all other patients.”

Within a week, the pharmacy team had set up a service that enabled patients to drive to a dedicated pharmacy and collect their medicines without having to get out of their car.

“They are met by a pharmacist, who gives them their medicines and they have the opportunity for a consultation,” says Ward. “Feedback has been overwhelming and positive from both patients and staff.”

She is now working out how the service will operate moving forward. “In the longer term this does open up new possibilities. The ‘drive through’ provides a patient-centred service with the opportunity to consult and support medicines optimisation in a safe and convenient environment.”

2. Seven-day pharmacy services

For Will Willson, director of pharmacy at East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust, offering a seven-day service had been part of the trust’s transformation plan for years, but had never reached fruition. However, after the pandemic showed the value of having clinical pharmacists in the hospital all week round, the business case for continuing the service has been signed off and funding secured.

“When the pandemic started, the mix of patients changed and we were looking at where we were going to have the most benefit,” he explains. This meant having pharmacists available for those at the “front door” of the hospital in acute medicine, where there was concern about medicines safety, and in ITU, where demand was increasing and staff were being redeployed.

“We went from a five-day service to seven days a week to support this rapid change,” he says. “That is difficult to sustain when your funding model is based around five days,” he adds, but it was achieved through the goodwill of staff.

The feedback from clinicians has been vital in building a case to keep the service going, he explains. From October 2020, the seven-day service will operate in acute medicine and the pharmacy team is considering how to offer the same service for ITU.

“None of these ideas are new, it’s just a question of circumstances,” says Willson, adding that there is an advantage to making a business case for a pharmacy service that has already been in place for a month.

3. Expanded pharmacy roles

Whether it is training pharmacists to work on critical care wards while coping with a barrage of changing information on COVID-19, pharmacy technicians learning new skills in making up medicines for use on COVID-19 wards, or clinical staff getting a better understanding of operational matters, there has been a lot of rapid training over the past few months.

“Because other activity decreased we were able to move staff into critical care, so we did rapid training,” says David Corral, chief pharmacist at Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. He explains that pharmacists were given information packs containing relevant training material and guidelines before attending a presentation on the basics of ITU by the lead pharmacist for surgery. The pharmacists then received personal protective equipment training and were taken to a “clean” ITU for 1:1 critical care sessions to put the theory into practice.

Clinical pharmacists at Luton and Dunstable University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust also received rapid training in critical care and chief pharmacist Mary Evans is keen to maintain the ability for more pharmacists to provide ITU support. “Our band 7s really stepped up and we don’t want to lose that going forward. That ability for our team to support ITU is really important.”

Our band 7s really stepped up and we don’t want to lose that going forward. That ability for our team to support ITU is really important

Pharmacy technicians have also gained new skills during the pandemic. “In our aseptic unit we quickly validated more staff, although in the end it wasn’t needed. It does give us more flexibility with skill mix,” says Corral.

For band 7 clinical pharmacists, having a taste of operational and systems change decisions that they would not normally get involved in could be helpful in their future careers, says Evans.

Clinical pharmacists took on a wide range of tasks, including setting up new intensive care wards or moving existing wards to a different area, which meant assessing medicine usage and storage requirements, dealing with multiple drug shortages, setting up new finance codes or changing stock control systems.

4. Closer collaboration with clinical colleagues

In such a fast-moving situation, the normal routes for sharing best practice and keeping up to date with the latest evidence do not apply. Pharmacists needed to learn from those in hospitals already seeing high numbers of COVID-19 patients.

Critical care pharmacists across the country were in constant communication through social media and WhatsApp as well as formal webinars, says Evans. “There was a lot of sharing and learning going on,” she says. “Nobody was holding on to information and that was a real positive.”

Likewise, leaders of primary, community and hospital pharmacy joined forces at a local level to solve problems. Watson describes the collaboration as “really heart-warming”. He says it has not just been about networking, but about getting things done.

One example is the development of a pharmacy-led discharge model for patients ready to leave the Nightingale hospital, with a clinical handover from the Nightingale clinical pharmacy team to a specialist primary care team.

“Our group of secondary, primary and community care were meeting virtually at least once a week, and the system collaboration that was sparked off because of local resilience is something we are not going to let go of.”

5. Autonomy to make decisions

Because decisions had to be made on the spot and problems solved quickly without the usual layers of bureaucracy, pharmacists were able to be creative and flexible in coming up with solutions, says Watson.

“Across the NHS generally we sometimes make life difficult for ourselves, creating reasons not to get to work on things quickly, thinking it needs to be perfect,” he adds.

Callaghan had only just started in her role when the pandemic hit. Those first few weeks were an incredibly stressful time for the team, which was moved onto a three-day rolling rota, she explains. “We had to think very quickly, there wasn’t time to plan as there was no guidance at that point.

“One of the main things for me has been the creativity and flexibility, and how quickly we responded.”

Ward agrees: “The energy to make things change and happen was electric. We set up the ‘drive through’ in a week and electronic prescribing in two weeks.”

The energy to make things change and happen was electric. We set up the ‘drive through’ in a week and electronic prescribing in two weeks

The team is now trying to build on that enthusiasm by developing a permanent location for the medicines collection point and improving the uptake of electronic prescribing.

Watson says setting up NHS Nightingale Hospital North East flagged up how effective it can be when people are given the autonomy to make decisions. “The constraints have been less; it’s about having to change and adapt at pace and there’s something about having the flexibility to come up with fresh ideas.”

David Heller, chief pharmacist at Surrey and Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust, says that he has delegated more of his responsibilities during the pandemic and this has been a really positive change.

“One of my key roles is to help others in my team achieve their ideas and we saw people really start to step up and take responsibility, and that felt great.”

One project he delegated was the drawing up of IV syringes in COVID-positive areas, and this has prompted his deputy to write a proposal for future options around having a central IV antibiotics service. “To see ideas start to happen is a terrific thing.”

6. Better support for staff wellbeing

As the Thursday evening clap for the NHS has shown, there has been a huge amount of appreciation for those working in hospitals. But what the crisis has also highlighted is the many different roles that keep a department or trust running smoothly.

“There needs to be a lot of credit given to [NHS England] regional pharmacists, who have been absolutely amazing, and our procurement teams have done a fantastic job as well,” says Evans. “[Procurement is] one of those things that many people don’t think about; it just happens in the background.”

Heller refers to the procurement team as the “unsung heroes” of probably every NHS trust. And while he is keen to stress that all members of his team have been fantastic, he also has specific praise for pharmacy assistants. “We had wards changing use at a moment’s notice. Their flexibility and willingness to respond was absolutely critical to the way our organisation worked.”

Evans adds: “There has been a real community feeling and we need to make sure those good things that have happened don’t get lost.”

There has been a real community feeling and we need to make sure those good things that have happened don’t get lost

There has also been lots of support for NHS staff, whether that’s through areas to rest, food sent to sustain those working on COVID-19 wards, free parking or psychological and emotional support for those who are struggling. Corral says his trust is looking into how to provide the psychological support that has been on offer during the pandemic in the long term, as well as at ways to show staff that they are appreciated.

“I don’t think you realise the stress you are under. It was very stressful at the beginning and adrenaline kept people going.

“One of our concerns is for staff who are shielding, because that could … be difficult for their mental health. We have someone who is in touch with them every week to make sure they’re alright.”

7. Remote working

The ability to work remotely is a key adaptation that is here to stay, predicts Heller. “We have a couple of staff members who are shielding, but they work in procurement [of medicines] and we have been able to provide them with laptops, and they are carrying on [doing their jobs] from home; that’s been revolutionary.”

Neither does Heller expect to stop organising online meetings, such as his Friday afternoon leadership meeting. Being able to hold this remotely during the pandemic has saved him hours of travel time. “The ability for me to do a full staff meeting with 60-odd people as a webinar and send it out across offices and homes keeps people connected,” he adds.

Others agree that remote working is here to stay, at least in some form, especially as the need to maintain social distancing continues.

Evans says the ability to conduct meetings remotely during the crisis has been really positive. “We merged with another trust on 1 April 2020 and, going forward, we will be using some of this technology to have routine cross-site meetings.”

However, she cautions that a balance needs to be found. “I wouldn’t want us to lose face-to-face [contact] completely because that’s where we build relationships,” she says.