Science Photo Library

After reading this article, individuals should be able to:

1. Understand the different phases of COVID-19 illness;

2. Effectively support patients experiencing ongoing or long-term symptoms of COVID-19;

3. Provide trustworthy information and advice to patients;

4. Recognise the signs and symptoms that require urgent referral.

The effects of COVID-19 have remained the focus of the world’s attention for more than a year now[1]. However, there has recently been more attention given to the impact of COVID-19 on patients who are experiencing ongoing symptoms beyond their acute illness[2].

This is because a growing subset of people continue to feel unwell following acute infection with SARs-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19[3–5]. According to the Office of National Statistics, over the four-week period ending 6 March 2021, an estimated 1.1 million people in England living in private households (i.e. not including halls of residence, prisons, schools, hospitals or care homes) were still experiencing symptoms more than four weeks after first feeling unwell[6]. The various phases of illness associated with COVID-19 have been defined and categorised into three stages[7,8]:

- Acute COVID-19 — the first four weeks following initial infection and, in most cases, patients are able to recover fully;

- Ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 — new or persistent symptoms are experienced 4–12 weeks after initial onset;

- Post-COVID syndrome — signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.

This article provides an overview of the diagnosis and management of ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 and post-COVID syndrome. It has been reviewed by a panel of expert clinical advisers and aims to provide pharmacy teams with the necessary information to effectively support patients.

Long COVID

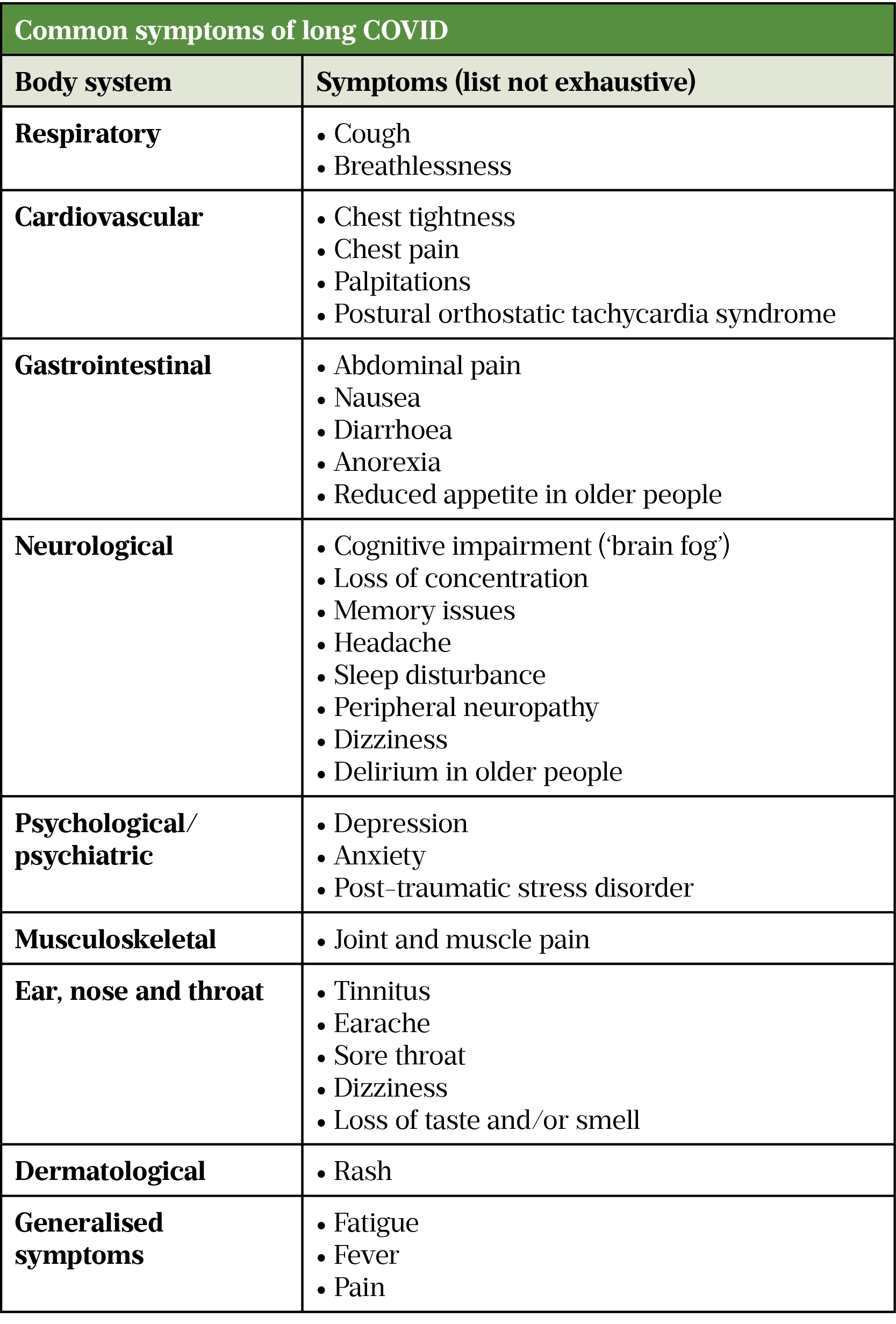

The term ‘long COVID’ was initially used by patients to describe their persistent and unexplainable symptoms following the diagnosis of COVID-19[9]. While it is not an official term, it is now commonly referred to when describing both ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 and post-COVID syndrome, where clusters of symptoms often overlap, fluctuate and change over time[7]. As with acute infection, symptoms of long COVID can involve multiple organ systems but can endure for months and continue to significantly impact a patient’s quality of life[3]. It is often characterised by persistent and fluctuating fatigue, breathlessness, cognitive dysfunction (‘brain fog’) and pain (see Table)[10].

Currently, there are few evidence-based approaches to support healthcare professionals diagnose and manage patients[8]. Published in December 2020, ‘COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19’ provides some guidance based on emerging evidence, as well as patient and clinician experiences[7,8].

The guideline is a product of a joint collaboration between the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), and follows a rapid review methodology[7,8]. While traditional guidelines usually take 24–36 months to develop, rapid reviews are a timely and affordable approach that can provide actionable and relevant recommendations produced within weeks to strengthen health policy and systems[11].

As SARs-CoV-2 is a new disease, long-term issues are still emerging and are not fully understood[7,8]. Much of the evidence is observational, retrospective data and the lived experience of patients and healthcare professionals is an important part of producing such guidance[12].

Although the guideline does not specifically refer to the role of pharmacists, it does acknowledge that management of long COVID requires a concerted multidisciplinary team approach, particularly in community and primary care[7,8].

Diagnosis

Currently, there is no formal diagnostic process for long COVID because symptoms are highly variable, wide ranging and associated with varying degrees of autonomic dysfunction[13,14]. The underlying cause is unknown, but one theory suggests symptoms associated with hyperinflammation may be caused by mast cell activation by SARS-CoV-2. However, more research is required to substantiate this[15,16].

The likelihood of a person developing long COVID is not thought to be linked to the severity of their acute illness (including whether or not they were admitted to hospital)[7]. Even so-called ‘mild, acute COVID-19’ may be associated with long-term symptoms, most commonly cough, low grade fever and fatigue, all of which may relapse and remit[17].

Other reported symptoms include shortness of breath, chest pain, headaches, neurocognitive difficulties, muscle pains and weakness, gastrointestinal upset, rashes, metabolic disruption (such as poor control of diabetes), thromboembolic conditions, as well as depression and other mental health conditions[18].

Cognitive and psychological symptoms should be assessed with the same level of importance as physical symptoms. Both can have a significant impact on quality of life and on an individual’s ability to work and carry out their usual daily activities[7,8]. Patients may also display signs of delirium (particularly in older people) and post-traumatic stress disorder (e.g. severe anxiety or uncontrollable thoughts related to their symptoms and the pandemic), of which pharmacists should be aware[19].

Skin rashes can take many forms, including vesicular, maculopapular, urticarial, or chilblain-like lesions on the extremities (so-called ‘COVID toe’, see Figure)[20]. There seems to be no need to refer or investigate these if the patient is otherwise well.

Science Photo Library

Recovery time is different for everyone and symptoms can change unpredictably, but for many people symptoms will resolve within 12 weeks[1,7]. Patients should be referred for medical review if symptoms persist and a medical diagnosis is required (see ‘Referral’)[7,8].

Pharmacists should therefore be aware of the signs and symptoms consistent with COVID-19 that develop during or after an infection, continue for more than four weeks and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis. Commonly reported symptoms of long COVID are summarised in the Table[7,8].

Sources: ([7,8,21–25])

Patient assessment

Concerned patients with new or ongoing symptoms four weeks or more after acute illness should be offered an initial consultation in conjunction with a clinical assessment[7,8]. It is important that patients should feel heard and not judged. Pharmacists may need to consult patients either in person or via remote consultation, and should ask the patient about the following[7,8]:

- Their history of suspected or confirmed acute COVID-19; for example:

- ‘Have you tested positive for COVID-19 in the past?’

- The nature and severity of previous and current symptoms; for example:

- ‘Please describe your symptoms to me’

- Timing and duration of symptoms since the start of acute COVID-19:

- ‘When did you first start to feel unwell?’

- ‘How long have you had each of these symptoms?’

- ‘How have your symptoms changed since you first became ill?’

- History of other health conditions, medications and complementary remedies; for example:

- ‘Do you have any other medical conditions’?

- ‘What medications do you take, including over-the-counter products, such as vitamins, supplements or herbal remedies?’

- Impact on day-to-day life, such as activities, feelings of social isolation, work, education and wellbeing; for example:

- ‘How do your symptoms impact your ability to work or carry out daily activities?’

- ‘How have your symptoms affected your mood?’

- ‘What support do you have at home and work?’

- Any feelings of worry or distress; for example:

- ‘What worries you the most about being unwell?’

These questions enable identification of the troublesome symptoms and risks for the patient in relation to COVID-19, whether any pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatment options are suitable and/or whether the patient would benefit from a medical review[7,8].

It may be beneficial for some patients to have a family member or carer present to provide support and/or aid in eliciting information and decision making[7,8].

Referral

Pharmacists should exercise their professional judgement and, if necessary, they should refer patients to a GP or a local post (long) COVID acute service[7,8]. A shared decision-making approach between pharmacists and patients should be employed to discuss and agree whether the patient requires medical referral, particularly for people in vulnerable or high-risk groups, such as those experiencing worsening frailty or people with dementia[7,8]. This is important to ensure patients have access to a multidisciplinary rehabilitation team that can focus on the physical, psychological and psychiatric aspects of care[7,8,22–25].

The following symptoms require urgent referral to acute or specialist services, and are indicative of an acute or life-threatening complication[7,8]:

- Severe or worsening shortness of breath (suspected hypoxaemia or oxygen desaturation on exercise or severe lung disease);

- Cardiac chest pain;

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome (in children);

- Severe dizziness;

- New confusion or difficulty speaking;

- Severe mental health issues (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder);

- Risk of self-harm or suicide.

In all instances where urgent referral is required, patients should be referred even in the absence of a positive COVID-19 test[7,8]. Routine testing has not always been available, particularly during the early and mid stages of the pandemic when risk of transmission was high. Consequently, many individuals may have had COVID-19 but were unaware and did not get tested.

Further tests and investigations

Once referred for a medical review, patients will undergo further tests and investigations tailored to the person’s signs and symptoms to rule out acute, life-threatening complications or underlying pathological causes, such as inflammatory bowel disease or cancer. These include blood tests (e.g. full blood count, renal and liver function tests, C-reactive protein, ferritin, B-type natriuretic peptide and thyroid function tests), exercise tolerance tests, blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation and chest X-rays[7,8].

Following medical review, patients may then be referred to relevant pathways between primary and community care, such as multidisciplinary rehabilitation and/or specialist services[7,8]. One example of such a service is the NHS Seacole Centre in Surrey, which provides physical, cognitive, psychological and psychiatric rehabilitation services for patients with long COVID and is staffed by more than 100 healthcare professionals, including nurses, physiotherapists and pharmacists[26]. At the time of publication these services were not available throughout the whole of the UK and those that do exist may be significantly overburdened. This makes appropriate pharmacy management in community and/or primary care even more important.

Management and advice

There is limited evidence on how to treat common COVID-19 specific symptoms, such as fatigue, dizziness and cognitive problems (e.g. brain fog)[7,8]. However, pharmacists should provide and offer tailored self-management support and information to all patients, as summarised below, and provide medicines optimisation support to people with long COVID who have pre-existing comorbidities, such as recommending prescribers titrate antidiabetic medication for patients experiencing hyperglycaemia post-steroid therapy[7,8].

Box: Information and advice for patients with long COVID [7,8]

Pharmacists should counsel patients on the following:

- How to use medicines correctly and as recommended by prescribers;

- Provide advice on how to manage symptoms:

- Guidance on how to set realistic health and wellbeing goals;

- Using a diary to record and track goals, symptoms, mood, impact on wellbeing, as well as any progress made;

- Advice on self-management and rehabilitation. The World Health Organization Rehabilitation self-management leaflet provides basic rehabilitation exercises and advice for adults who have been severely unwell and were admitted to hospital with COVID-19;

- For symptoms of anxiety, depression and sleep disturbances, advise on sleep hygiene and techniques for managing stress and anxiety. The following pages may be useful to signpost to:

- At home, self-monitoring of heart rate, blood pressure and pulse oximetry, if supported by their GP, multidisciplinary rehabilitation service or if patients have access to wearable technology (e.g. smart devices). Ensure patients have clear instructions and know when to seek help.

- Pharmacists should advise patients who are planning to return to physical activity to consult their GP first because a cardiac or respiratory assessment may be required. Inform patients that:

- Gentle exercise may help to improve strength, but any activity should be undertaken cautiously under medical supervision and tailored to the severity of symptoms;

- Progress may be slow and it may not be possible to return to pre-COVID fitness levels;

- It is important to take regular rest periods when needed;

- Urgent medical advice is needed if patients start to experience severe shortness of breath or chest pain.

- Ensure patients know who to contact if they are worried about their symptoms or if they need support with self-management. For example, their GP, multidisciplinary rehabilitation team or relevant specialist service;

- Signpost to reliable resources for more information and advice about symptoms and ongoing care. For example:

- SIGN Long COVID patient booklet;

- NHS ‘Long-term effects of coronavirus (long COVID)’ page;

- NHS England ‘Your COVID recovery interactive web-based programme’ (support for people experiencing symptoms of long COVID);

- NHS Inform ‘Longer-term effects (long COVID)’ page.

- Ensure patients know how to seek help from other services or groups if needed, including:

- Support groups (pharmacists should advise patients that not all advice shared, particularly through social media, is accurate or evidence-based and to double check first with a registered healthcare professional);

- Provide information about new or continuing symptoms of COVID-19 that the person can share with their family, carers and friends (see Table);

- Inform patients that it is not known if over-the-counter vitamins and supplements are helpful, harmful or have no effect in the treatment of new or ongoing symptoms of COVID-19, and may interact with prescribed medicines (e.g. niacin and statins);

- Discourage patients from the illegal online purchase or importation of medicines (e.g. ranitidine). Also advise patients against taking medicines that have not been prescribed specifically for them, but may have been prescribed for a friend or family member (i.e. sharing medicines).

Summary

Management of persistent COVID-19 symptoms requires multidisciplinary input, particularly in primary care. Pharmacists should support patients who are experiencing prolonged symptoms by ensuring concerns are heard, providing advice on symptom management and recognising when further medical review is required.

Acknowledgements

The Pharmaceutical Journal would like to thank and acknowledge the following clinical advisers whose expertise and insight have contributed to the development of this article:

- Arlene Coulson, lead clinical pharmacist, surgery and specialist services, NHS Tayside; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) council representative (Royal Pharmaceutical Society);

- Geraint Jones, expert patient and advanced pharmacist, HIV and homecare, Cwm Taf University Health Board;

- Cathrine McKenzie, clinical academic research lead (pharmacy), Kings College Hospital

- Angela Timoney, director of pharmacy, NHS Lothian; chair of SIGN;

- Stephen Ward, clinical pharmacy lead, Belfast City Hospital, Belfast Health and Social Care Trust.

- 1Everything you should know about the coronavirus pandemic. The Pharmaceutical Journal Published Online First: 2021. doi:10.1211/pj.2021.20207629

- 2Garner P. Covid-19 and fatigue — a game of snakes and ladders. The BMJ Opinion. 2020.https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/05/19/paul-garner-covid-19-and-fatigue-a-game-of-snakes-and-ladders/ (accessed May 2021).

- 3Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, et al. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ 2020;:m3026. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3026

- 4Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, et al. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020;324:603. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12603

- 5Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. The Lancet 2021;397:220–32. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32656-8

- 6Office for National Statistics . Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK. Statistical Bulletin. 2021.https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/1april2021 (accessed May 2021).

- 7National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Royal College of General Practitioners, Healthcare Improvement Scotland SIGN . COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. . 2020.www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188 (accessed May 2021).

- 8Healthcare Improvement Scotland . COVID-19 rapid evidence review: managing the long term effects of COVID-19: the views and experiences of patients, their families and carers. . 2021.www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines/managing-the-long-term-effects-of-covid-19 (accessed May 2021).

- 9Perego E, Callard F, Stras L. Why we need to keep using the patient made term “Long Covid”. BMJ Opinion. 2020.https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/10/01/why-we-need-to-keep-using-the-patient-made-term-long-covid/ (accessed May 2021).

- 10Royal Pharmaceutical Society . COVID-19 queries. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2021.https://www.rpharms.com/resources/pharmacy-guides/coronavirus-covid-19/guidance-for-pharmacy/covid-queries#long (accessed May 2021).

- 11Tricco AC, Langlois EV, Straus SE, editors. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. World Health Organization, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research 2017.

- 12Gorna R, MacDermott N, Rayner C, et al. Long COVID guidelines need to reflect lived experience. The Lancet 2021;397:455–7. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32705-7

- 13Dani M, Dirksen A, Taraborrelli P, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in ‘long COVID’: rationale, physiology and management strategies. Clin Med 2020;21:e63–7. doi:10.7861/clinmed.2020-0896

- 14Goodman BP, Khoury JA, Blair JE, et al. COVID-19 Dysautonomia. Front Neurol 2021;12. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.624968

- 15Afrin LB, Weinstock LB, Molderings GJ. Covid-19 hyperinflammation and post-Covid-19 illness may be rooted in mast cell activation syndrome. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020;100:327–32. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.016

- 16Theoharides TC. Potential association of mast cells with coronavirus disease 2019. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2021;126:217–8. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2020.11.003

- 17King’s College London . COVID Symptom Study. How long does COVID-19 last? King’s College London. 2020.https://covid19.joinzoe.com/post/covid-long-term?fbclid=IwAR1RxIcmmdL-EFjh_aI- (accessed May 2021).

- 18Dasgupta A, Kalhan A, Kalra S. Long term complications and rehabilitation of COVID-19 patients. J Pak Med Assoc 2020;:1. doi:10.5455/jpma.32

- 19NHS England . NHS to offer ‘long covid’ sufferers help at specialist centres. NHS England. 2020.https://www.england.nhs.uk/2020/10/nhs-to-offer-long-covid-help/ (accessed May 2021).

- 20Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID ‐19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol 2020;183:71–7. doi:10.1111/bjd.19163

- 21Schofield J. Persistent Antiphospholipid Antibodies, Mast Cell Activation Syndrome, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome and Post-COVID Syndrome: 1 Year On. European Journal of Case Reports in Internal Medicine Published Online First: 22 March 2021. doi:10.12890/2021_002378

- 22Naidu SB, Shah AJ, Saigal A, et al. The high mental health burden of “Long COVID” and its association with on-going physical and respiratory symptoms in all adults discharged from hospital. Eur Respir J 2021;:2004364. doi:10.1183/13993003.04364-2020

- 23Mahase E. Covid-19: Nearly 20% of patients receive psychiatric diagnosis within three months of covid, study finds. BMJ 2020;:m4386. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4386

- 24Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, et al. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. The Lancet Psychiatry 2021;8:416–27. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(21)00084-5

- 25Smith CM, Komisar JR, Mourad A, et al. COVID-19-associated brief psychotic disorder. BMJ Case Rep 2020;13:e236940. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-236940

- 26‘I could barely function’ – the devastating effects of long COVID. The Pharmaceutical Journal Published Online First: 2020. doi:10.1211/pj.2020.20208498