As nations around the world seek to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become apparent that the toolbox of modalities employed is greatly dependent on the political leadership in question. Some leaders have chosen to respond to the crisis with coercive and opaque methods, while others have chosen more consultative and open approaches. Observing the potential and preliminary outcomes of such responses is essential to understanding how different types of leadership can impact nations, both positively and negatively, during a public health crisis.

Several authoritarian-minded leaders have exploited the pandemic, as leaders make decisions and impose policies that allow them to abuse their authority, threaten civil liberties, centralize control, amass greater power and implement increased surveillance.1 These strategies have often prioritized personal, political and economic interests,2 with certain authoritarian regimes relying on the pandemic to justify the development of policies that are regressive in nature,3 and that may, in some cases, pose a threat to human rights.4 Authoritarian leaders may shift to politically biased claims rather than factual ones, discrediting or diminishing the value of experts, in particular those experts concerned with public health. While some authoritarian nations have aimed to address the crisis through interventionist policies and heavy surveillance, they have appeared to act slowly, often withholding information from the public and focusing on controlling the media. In contrast to this authoritarian approach, an open and collaborative governmental process develops policies through information and data sharing, encouraging the involvement of the scientific community.5

This paper analyzes a variety of leadership styles observed during the pandemic, using evidence from scholarly research on leadership and recently published articles from the mainstream press on the effectiveness of pandemic responses. We share preliminary observations on leadership approaches, including differing degrees of reliance on expert advice and differing degrees of centralizing control over citizens, alongside outcomes such as approval ratings, the response of the international community, and the country’s effectiveness in containing the pandemic.

Important Characteristics of Leadership

In a crisis, citizens are likely to look to political figures and other powerful individuals for guidance. A key characteristic of effective political leadership during a crisis is the ability to consider the needs of citizens over the leader’s individual interests or the interests of the regime they govern.6 Approaches to leadership that focus on gaining respect and trust, as well as going beyond personal interests to exhibit self-sacrificial behaviour for the good of others, are also perceived particularly well in times of crisis.7 This is especially applicable to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Leaders who have chosen to respond to the pandemic with the public’s health needs at the forefront of national policy, by considering the advice of experts and representatives from diverse backgrounds, have been well perceived by citizens and media outlets around the globe.8 Desirable leadership traits also include the ability to choose group members with skills that create direct benefits for the population at large.9 In the COVID-19 context, this included leaders who chose skilled members of the pandemic response team in an effort to appropriately manage the crisis.

Authoritarian and Nationalistic Approaches During a Pandemic

Depending on both the leader and structure of government, responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have varied. Some authoritarian leaders have introduced strict lockdown measures and protocols, while others have chosen to deny or neglect the crisis entirely. To fully understand the potential impact of this style of leadership, it is important to examine the specific characteristics of an authoritarian approach.

Authoritarian leaders often demand that their subordinates obey their instructions without questioning them.10 In the current pandemic scenario, these types of leaders have typically announced lockdown measures without provision for citizens to question or refuse them, regardless of how restrictive these measure are. Authoritarian leaders also tend to implement a top-down style of governing that highlights power asymmetry between the leader and followers, ultimately resulting in the leader withholding information and reducing the quality of communication within and beyond the state.11 This approach, as we have seen during the pandemic, leaves less room for scientists and professionals of various kinds to be heard.

At the time of writing, nations have chosen to share data concerning the COVID-19 pandemic in a variety of ways. While nationalistic and authoritarian leaders both prioritize the sovereign principle of national self-determination, it should be noted that they have little significant influence on one another.12 However, in spite of contrasting leadership styles, the responses elicited by each have been found, in many cases, to be similar. Not only did authoritarian governments withhold essential information during the initial outbreak, but nationalistic leaders who viewed the pandemic with skepticism and anti-scientific views seemed to communicate uncertainty and denial.13 The latter approach was evident in the United States, where President Donald Trump initially provided minimal information to the public and blamed the Democratic Party for inflaming the situation, with little being done to inform citizens about potential risks, even though, at the time the statements were being made, the virus was widely circulating in Washington.14

While a lack of open and honest communication has been evident in democratic societies with nationalistic leaders, this may be a larger issue in authoritarian governments in which information sharing is even more limited. In China, President Xi Jinping was criticized for a lack of transparency domestically, but even more so internationally, for his muted response to the initial phases of the pandemic — a response that may have been one of the greatest contributors to the global spread of the virus.15 Moreover, Xi’s strict censorship made it difficult for the Chinese medical community to speak out, and those who did try to sound the alarm were reprimanded by authorities.16 Russian president Vladimir Putin not only failed to communicate the seriousness of the virus for many months, but initially downplayed the numbers of infected persons and ridiculed his opponents for their concern, all of which was made possible by his strict control of the Russian media.17 Authoritarian leaders also tend to make unilateral decisions that are detrimental to their citizens, instead of consulting with experts whose informed views are likely to lead to better decision making.18 This lack of consultation ultimately hinders transparent communication between a leader and their citizens, and creates unequal hierarchies between those in government and the medical professionals who could potentially provide effective input on how to respond to the pandemic.

The active measures taken by certain governments to limit transmission of the virus is another important leadership factor to consider. While the application of such measures is important, it is critical that leaders ensure that, in implementing these measures, citizens’ rights are not needlessly violated. China’s strategies to control the virus included electronic surveillance,19 or the use of technology to control the individual freedom of movement within the country. For example, the Chinese government has started to use digital applications to track individuals and colour-code these individuals based on their data, so as to restrict movement depending on perceived risk. Individuals who left their homes were required to present to authorities their colour determination on the application; something which could have impacted their ability to obtain medical care and other necessities or earn a living, or invited inappropriate use supporting claims regarding perceived threats to the state.20 While tracking citizens’ movements may be necessary to control a public health outbreak, such extreme measures raise concerns as to where data is stored, how it is used, who has access to it, and whether such protocols will remain in effect after the crisis is over.

Authoritarian leaders have also used their positions to develop legislation strengthening their own powers. Many responses to the pandemic have raised concerns over leaders who may be exploiting the crisis to implement measures that serve their own interests and unnecessarily restrict the civil liberties of citizens. In Hungary, for instance, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán implemented lockdown measures, accompanied by strict curfews, that secured an indefinite state of emergency that enabled him to rule by decree. This had the effect of centralizing power and further eroding democracy in the country.21

Potential Advantages of Authoritarian Responses

Although at times unnecessarily coercive, authoritarian methods allow for mandatory responses to be carried out rapidly. More decentralized, participatory structures may be less nimble, as decisions have to be analyzed and approved at various levels. In circumstances where time is of the essence, the rapidly executed and enforced decisions of authoritarian leaders may, in some cases, be beneficial. For instance, the establishment of two 1,000-bed hospitals that were built within days in China, along with rapid restrictions on transportation and travel in certain regions of that country, were facilitated by a level of government control characteristic of authoritarian governments.22 Additionally, although the surveillance measures in these countries have raised concerns over rights violations, such courses of action could potentially provide advantages in managing a public health crisis, as they could aid in disease prevention, follow-ups on patients and epidemiological monitoring.23

While it is difficult to evaluate how effective surveillance measures may be, as current measures in countries such as China have lacked transparency, the public health benefits of monitoring citizens and their movements have been especially evident in the monitoring and management of urban areas. In these areas, surveillance technologies have been found to produce in-depth databases and efficient real-time information, especially when such practices have ensured that data privacy and security requirements are not breached.24 The use of surveillance appears to be most problematic when ethical standards are not met in collecting and storing personal data. Although the Taiwanese government used surveillance measures through SIM cards within mobile phones and data housed within their nearby base stations, it stated that it would do so only during the period of mandatory quarantine and without the use of illegal or advanced surveillance technology.25

Transparent and Collaborative Leadership

At the time of writing, it is still too early to conclude how authoritarian styles of leadership will impact COVID-19 recovery rates over the long term. However, favourable outcomes have been noted with leaders who have used more transparent and collaborative techniques, such as consulting with public health officials and providing timely and accurate information to citizens.26

Within this leadership cadre, some nations embraced collaboration of other stakeholders in decision making. Sweden’s decisions early on in the pandemic not to restrict access and mobility in similar ways to other democratic countries stemmed largely from the country’s technocratic style of policy making, which features expert authorities and commissions playing an important role in addressing key policy issues. Based on voluntary measures recommended by the Public Health Agency of Sweden, Sweden implemented less restrictive social distancing guidelines than many countries.27 This technocratic approach to policy-making encouraged citizens to self-regulate during the pandemic; an approach which requires a high degree of mutual trust between citizens and their government, with responsibility delegated to individuals, and a reliance on education and social approval rather than a top-down system of control.28

We can also observe many successes among those women in leadership positions who have responded to the pandemic by taking a collaborative approach to making policy decisions.29 This is not to say that all men in leadership positions have responded negatively, but rather that a large number of the decisions that female leaders have taken have been well-received by their citizens, with several female leaders being particularly successful in containing the virus.30 In Taiwan, President Tsai Ing-wen collaborated with a variety of agencies and gave daily press briefings to the public.31 While regular briefings were carried out in a variety of nations since the outbreak, some leaders appear to have done a more effective job of communicating than others.

In contrast with the Taiwanese method, President Trump’s daily briefings, although sporadically involving scientists and medical professionals, often disregarded scientific evidence and conveyed messages of uncertainty; the president has even mused about dubious “solutions” to the virus such as the injection of disinfectant or the internal administration of light.32 By publicly contradicting the guidelines and advisories of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — regarding masking, social distancing and the shutdown and re-opening of the economy, for example — the US President repeatedly undermined public health officials.33 An infamous example was his announcement that hydroxychloroquine showed encouraging results for treatment of COVID-19 and that the Food and Drug Administration had approved its use for this purpose. Both statements proved to be false.34 President Trump’s press conferences claiming that foreign governments, the Deep State and Democratic governors were all mismanaging the manufacture and distribution of ventilators, and preventing the development of a vaccine, seemed designed to deflect responsibility and confuse rather than to take responsibility and set a clear example of protocols and behaviours to follow.

On the other hand, daily press briefings in Taiwan were held with the intent to fight misinformation by consistently involving the advice of the minister of Health and Welfare as well as the vice president of Taiwan, the latter of whom is also a prominent epidemiologist.35 Such actions allowed for professionals from a variety of fields to apply their expertise to the response protocols while keeping the public informed. Tsai’s response to the coronavirus has been described as ‘warm yet authoritative’ and, as a result of strategically enacting more than 100 control and contain measures, Taiwan became a leader in COVID-19 crisis management, later assisting other countries in their own national pandemic strategies.36

While it is difficult to measure exactly how open communication strategies impact case numbers, studies have found that providing accurate and credible information during a pandemic can help protect the public’s health and save lives.37 In New Zealand, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern took an empathetic and transparent approach to leadership since the onset of the pandemic. She urged citizens to unite as a team against the virus, while ensuring the utmost clarity when delivering health notices and messages to the public.38 At the time of writing, the country has recorded only 1,824 confirmed cases of the coronavirus and 25 deaths.39

Domestic and International Observations

Where open, collaborative and empathetic leadership has been found to be effective in controlling the spread of the virus, other positive impacts have accrued to the leaders themselves. Those who have embraced a communicative style of leadership have seen their approval ratings improve significantly. Following the implementation of response measures in Taiwan, Tsai’s overall approval rating was close to 70 percent, with her minister of Health and Welfare receiving approval ratings of more than 80 percent.40 Similar trends were observed among other leaders who prioritized the transparent communication of medical advice. In Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s calm expositions, backed with clear scientific explanations of the government’s lockdown exit strategy, helped to increase public approval of her response to the crisis to above 70 percent.41

Although domestic approval ratings have remained strong for many different types of government during the pandemic, restrictive and controlling governments have elicited criticism from the international community over their infringement on civil liberties in times of crises.42 These external criticisms often stemmed from western actors. In Hungary, for example, where Orbán’s ruling Fidesz party only became stronger through its implementation of emergency procedures, the Council of Europe and the European Parliament publicly denounced the Hungarian government’s actions during the pandemic.43 It is important to be conscious that criticisms are likely to arise from actors with an ideological viewpoint that is inherently different from the one they condemn.

Evidently, a number of unintended consequences arose from the various leadership approaches and actions of leaders around the world, including the domestic and international approvals and objections. However, it should be noted that strong approval of leadership may not, in itself, be evidence of success. System justification theory argues that perceived threats often lead individuals to increase trust in authorities such as governments, and people are thus more likely to justify and rationalize the way things are, even when political systems negatively affect their interests.44 For these reasons, high domestic approval ratings of leaders in light of the fear and uncertainty that a pandemic or crisis provokes, must be interpreted carefully. Examining how leaders are perceived by a variety of stakeholders, including the international community, can provide greater insight into the ways that different approaches and procedures have been evaluated.

Conclusion

The decisions made by some authoritarian leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic ignored scientific evidence regarding the virus and used the pandemic to justify actions favourable to their own self-interest. On the other hand, leaders who placed scientific data and expertise — rather than their own political and economic interests — at the forefront of policy making, have, thus far, managed to control their case numbers and earn the trust of their citizens. By taking on a more collaborative perspective, countries can work together, not only with professionals within their own nations but also on an international scale, to tackle the coronavirus pandemic.

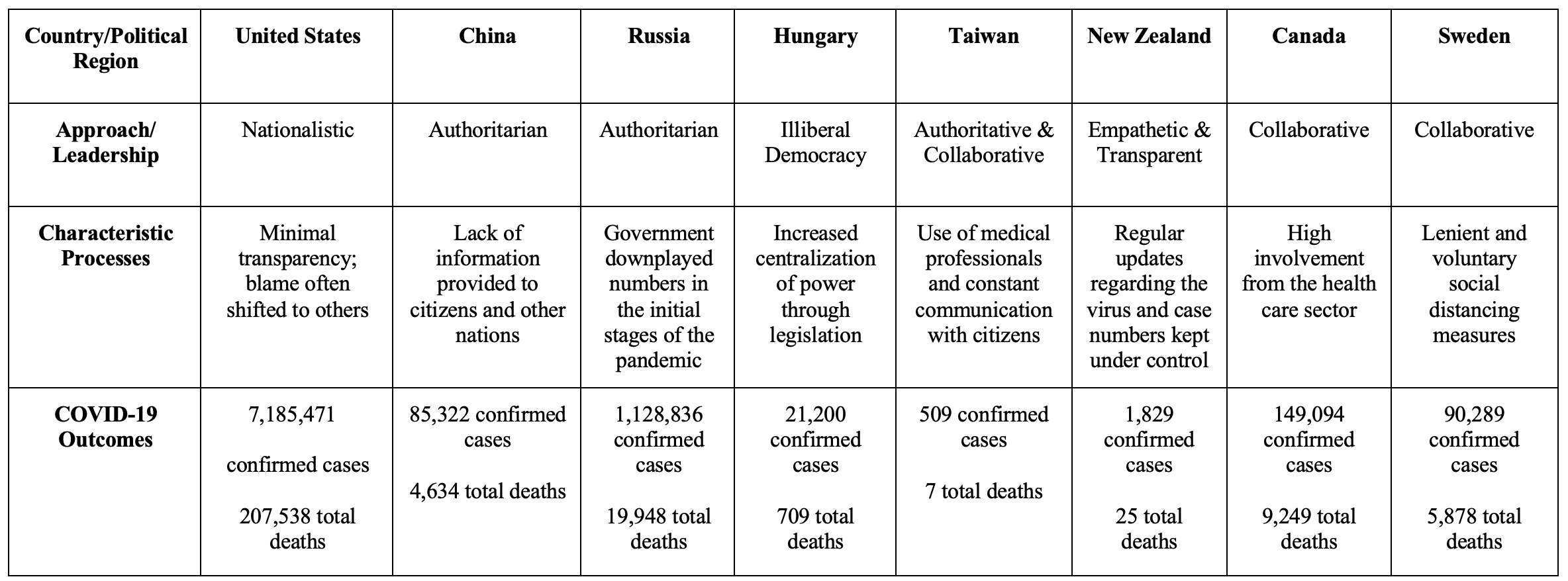

Table 1 indicates the main approaches that have been analyzed within this paper, focussing on selected leaders in North America, Europe and Asia. The data indicates that the countries listed vary greatly in terms of geography, timing of exposure to hotspots, travel patterns and so forth. Governments have different strategies for testing and therefore factors such as the type of testing used, the particular populations being targeted, and the number of people being tested vary among nations. The ways that COVID-19-related deaths and case numbers are determined also differ. Countries that are geographically, socio-culturally and economically close may be more accurately compared than those in which these categories differ by orders of magnitude. For all these reasons, when comparing absolute numbers, caution must be applied.

While it is difficult to draw conclusions about how leadership styles directly impact infection rates, it is clear that the immediate impacts of authoritarian leaders have resulted in increased distrust and fear in already uncertain times, even though leaders’ approval ratings have remained high.

The ideal style of leadership during a crisis centres on the use of experts, with empathetic and collaborative leaders placing greater focus on trust than on power and control. This allows for the development and implementation of policies that place the interests of citizens at the forefront of policy and ultimately lead to increased trust and transparency. However, since the COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented in living memory, and since we have only a glimpse of the short-term outcomes that each leadership style has elicited, it may take years before we are able to fully assess the long-term impacts of measures such as surveillance on the freedom and well-being of citizens. For now, we can only observe and attempt to learn lessons in real time, as together we navigate these challenging times across the globe.