Introduction

Organizations operate in highly volatile environments (Spillan and Crandall, 2002). As the environment is becoming increasingly complex, the crises that organizations face will also increase not only in extent but also in impact (Spillan, 2003). As Mitroff and Anagnos (2001, p. 3) state, “crises have become an inevitable, natural feature of our everyday lives”. The demands of day-to-day operations and crisis management are particularly important and challenging, and organizations need to implement crisis management plans and create teams to achieve business continuity (Spillan, 2003). The level of crisis preparedness, as well as the ability to detect crises at an early stage, are crucial (Schwarz and Pforr, 2011). For decades, planning and crisis management have been recognized as important areas of management, by both practitioners and academics (Spillan, 2003). According to Caponigro (2000) and Spillan (2003), crisis management is the function that works to minimize the impact of unexpected, unfortunate, and catastrophic events, and helps the organization gain control of the situation. Crisis management, the impact planning process, and crisis mitigation are important strategic concerns that must be incorporated into an organization’s overall planning process (Spillan and Crandall, 2002). The ability to manage a crisis can determine survival and disaster (Spillan and Crandall, 2002); however, some organizations consider crisis planning and management important, others less so (Spillan, 2003).

The extent to which the NPOs are strategically prepared to deal with crises is an unknown fact (Schwarz and Pforr, 2011). The literature on crisis management is abundant, but regarding NPOs, little has been written on the subject, given that few studies have explored the crisis management of the NPOs (Spillan, 2003). In the same way, the preparation of the NPOs crisis communication has received little attention in the investigation (Schwarz and Pforr, 2011), where although crisis communication remains a hot topic in Public Relations literature, there has been little attention to strategic responses to the crisis in NPOs. This may be an indicator that many managers of these organizations are not aware of or ignore the risks and vulnerabilities that exist in their organizations (Spillan and Crandall, 2002). Most of the crisis management literature addresses the profit sector. However, NPOs must also plan for the unthinkable (Spillan and Crandall, 2002).

Addressing this literature gap, the forthcoming qualitative study aims to better know about crises in NPOs. Specifically, it intends to capture the critical issues of concern by leadership, the level of preparedness for crises, and, in case NPOs lack preparedness, the reasons or motives for the lack of preparation and planning. Finally, this study gets to better know what are the activities and practices that can expand crisis management planning and prevention.

The article proceeds as follows. First, with the research background in mind, it separates crisis management, in general, from crisis management planning in the NPOs sector. Doing so allows the knowledge of this field to be adapted to this specific context, browsing themes as types of crises and their phases. Second, it presents the methods carried out in this phase of the study and clarifies the data collection process. It also examines and discusses preliminary results obtained on this exploratory field study to be explored. Finally, conclusions and implications for further research are drawn.

Crisis Management

With the perspective that time allows, today, one can easily identify the 60s of the 20th Century as the beginning of the literature about organizational crises (Mendes and Pereira, 2006). One of the first authors to write about this subject was Charles Hermann, in 1963, and his concern was to analyze the consequences that certain disruptive phenomena, which he called crises, had on the viability of organizations. This author defined a crisis as something that threatens the fundamental values of the organization, allows only a limited period for decision making, is unexpected by the organization, and originates in the relevant environment of the organization (Hermann, 1963). Fink (2002, cit. in Wrigley, Salmon and Park, 2003), one of the leading authors in the field, conceptualizes crisis as something that, positively and negatively, impacts an organization and as something (time, phase, or event) that is decisive or crucial. Devlin (2007, p. 5) refers to a crisis as “an unstable time for an organization, with a distinct possibility for an undesirable outcome. This undesirable outcome could interfere with the normal operations of the organization, it could damage the bottom line, it could jeopardize the public image, or it could close media or government scrutiny”. Seeger et al. (2003, cit. in Jordan, Upright and Tice-Owens, 2016, p. 162) add on the definition of a crisis as “a specific, unexpected and non-routine organizationally based event or series of events which creates high levels of uncertainty, and the threat or perceived threat to an organization’s high priority goals”.

A crisis starts from the onset of illness, which is accentuated, and draws the attention of the organization and causes disruption of the business routine and, consequently, threatens the reputation and financial viability of the organization (Fink, 2002, cit. in Wrigley, Salmon and Park, 2003). Pauchant, Mitroff, and Ventolo (1992) and Ulmer (2001) also share the crisis trilogy developed by Fink (2002, cit. in Wrigley, Salmon, and Park, 2003): disruption, threat, and potentially negative consequences for the organization. The authors highlight that a crisis is a serious and critical phase in the evolution of things or situations. It is a rupture, a disturbance in the organization’s balance. It is a turning point characterized by great instability that can result in undesirable consequences, affect the organization’s reputation, and hence produce negative public notoriety.

Although crises can arise in infinite sizes, shapes, intensity, complexity, uncertainty, and magnitudes (Eriksson and McConnell, 2011), in the opinion of Marcus and Goodman (1991), different types of crises can be distinguished, such as accidents, scandals, product safety, and health incidents. According to Devlin (2007), there is a panoply of types of crises, which can range from fires, floods, tornadoes, bombings, earthquakes, product failure, a product market-shifts, a product safety issue, an incident that results in a poor image or negative reputation, a financial problem, and so on. Regarding the types of crises, it should be noted that any organization is sensitive to an endless number of crises. For this matter, there is an immense number of classifications of crisis events in the literature. Crisis management researchers have classified crises into 2×2 matrix (e. g. Meyers and Holusha, 1986; Marcus and Goodman, 1991; Coombs and Holladay, 1996), through cluster analysis Pearson and Mitroff (1993), and by categories (Spillan, 2003; Devlin, 2007; Crandall, Parnell and Spillan, 2014). Also, recommendations for crisis management usually take a developmental stage approach (Jordan, Upright, and Tice-Owens, 2016) as models range from three to five stages or phases.

Because the world, and in particular, the North of Portugal, is still in a pandemic situation, this study focuses on the first two phases of Coombs (2012) and Coombs and Laufer (2018): pre-crisis phase, and crisis phase. In this sense, the pre-crisis phase involves the prevention, and preparation for crises to minimize damage to the organization (Coombs and Laufer, 2018). This stage includes activities, such as signal detection and prevention which include knowing potential areas of vulnerability, evaluating potential crisis types, preparing a crisis management team, selecting, and training an organizational spokesperson, developing a crisis management plan, and preparing organizational communication systems (Coombs, 2012). The crisis management plan (CMP) developed during the pre-crisis stage, as some advocates (Coombs, 2012), should explain whom to contact when to contact them, and how to contact them (Seeger et al., 2003, cit. in Jordan, Upright and Tice-Owens, 2016). Additionally, within this stage, organizations should extend their issue management to their active social media platforms because problems or concerns of individuals may now go viral (Jordan, Upright, and Tice-Owens, 2016). Coombs (2012) agrees that social media has implications for crisis management and has a role in crisis management, ranging from pre-crisis monitoring of warning signs to post-crisis communication. Concerning the crisis phase, this phase represents the response to the crisis, including the response of the organization and its stakeholders (Coombs and Laufer, 2018). The crisis response is what management does and says after the crisis hits (Coombs, 2012) to limit the effects. Pearson and Mitroff (1993, p. 53) call this phase “damage containment”. Effective management of this phase must go through plans to prevent a localized crisis from affecting other uncontaminated parts of the organization or its environment, for example, through evacuation plans or procedures for neutralizing or damage containment mechanisms and activities (Pearson and Mitroff, 1993).

Crisis management planning in the NPOs sector

Despite their status, being some of the least understood segments of society, NPOs are among the most crucial ones (Waters, 2014), and are not immune to crises (Spillan, 2003; Wrigley, Salmon and Park, 2003; Schwarz and Pforr, 2011; Sisco, 2012; Jordan, Upright and Tice-Owens, 2016). NPOs play an increasingly influential role in economies and societies as a catalyst for new approaches and service provision, and a crucial actor in social and economic life (Salamon and Anheier, 1992; Spillan, 2003; Crandall, Parnell and Spillan, 2014).

NPOs are extremely vulnerable organizations in times of crisis (Sisco, 2012). Patterson and Radtke (2009, cit. in Jordan, Upright and Tice-Owens, 2016) mention that nonprofit organizations face one of two types of crises: emergencies and controversies. On one hand, an emergency may result in injury to individuals, damage to or loss of facilities, financial loss, or lapses in services (Patterson and Radtke 2009, cit. in Jordan, Upright and Tice- Owens, 2016). Emergencies differ from routine events in terms of critical and timely information requirements and a high level of uncertainty (Kapucu, 2007). On the other hand, controversies may damage an organization`s reputation because of fraud or accusations, legal difficulties, or challenges to organizational leadership integrity and effectiveness (Patterson and Radtke 2009, cit. in Jordan, Upright and Tice-Owens, 2016). According to Jordan, Upright, and Tice-Owens (2016), during crises, NPOs face increased pressure for accountability through different organizational practices, as the organization, its stakeholders, and the community at large try to survive the crisis. Furthermore, these entities should be prepared for common potential crises, considering that time spent in preparing helps leaders navigate through the crisis (Coombs, 2012).

Methods

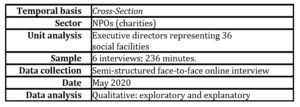

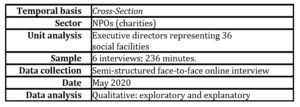

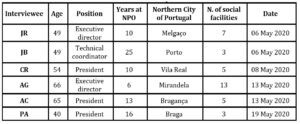

This investigation uses a two-part data collection process. Qualitative and quantitative data will be connected during the phases of research, following a mixed-method approach (Creswell, 2003). Based on the literature review, it started with an exploratory qualitative data collection, where data analysis and its results will be used to inform the quantitative phase developed subsequently. This study is the beginning of a larger researcher project. The qualitative study included six in-depth semi-structured face-to-face online interviews with key informants of six Northern Portuguese NPOs, including 36 different social facilities, carried out in May 2020 (see Table 1). The interviews conducted were semi-structured, thus questions prepared in advance were mixed with questions that emerged during the interview. Semi-structured questions were chosen since they have proven efficient when using a case study approach (Creswell, 2003). The interview duration was approximately 40 minutes per interview. Both authors were present in all interviews. All interviews were taped, transcribed, and analyzed. Data were categorized, and transcripts were repeatedly read during this analysis.

Table 1 – Methodological overviews of the interviews

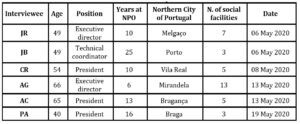

The sampling for the interview process was carried out for convenience, encompassing a total of six executive directors of NPOs in the North of Portugal,

according to the list in Table 2. The respondents are familiar with the context considering their experience amount. The NPOs, they represent, deal with a variety of social issues as drugs dependency, elderly, childhood, homeless, among others.

Table 2 – List of respondents

Results And Discussion

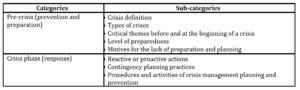

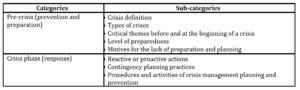

Based on the script (see appendix) and considering the research objectives, it was possible to outline an analysis grid (Table 3) for the interviews carried out with the six executive directors. The presentation of the data will be structured and illustrated by explanatory excerpts of the positions taken by the interviewees about each of the categories and sub-categories inspired by the work of Coombs and Laufer (2018).

Table 3 – Categorization structure of the interview process

The following section of the article presents, in a structured way, some of the data and information obtained through the interviews, for each of the categories under analysis.

Pre-crisis (prevention and preparation)

Crisis definition

When people think about crises, they think about unprecedented events that result in catastrophic damage and mass casualties. However, not all crises fall into this category. So, the problem with associating only catastrophic events with crises is that they sound so dramatic that most leaders assume an “it can’t happen to us” mentality (Crandall, Parnell & Spillan, 2014). The interviewees mention this clearly:

“We think it only happens to others and it doesn’t happen to us.” (CR)

In common with the interviews, the literature reveals that researchers, when defining a crisis, use words such as ‘surprise, insufficient information, event escalation, loss of control, intense scrutiny, panic, urgency, loss, disruption of normal activities, and threat to financial stability, creditability, and reputation’ (Coombs, 2002, cit. in Jordan et al. 2016). For instance:

“Crisis is everything that differs from what is normally functioning and always causes a moment of adaptation.” (PA)

“This crisis that fell on us … has a very heavy burden … so hell fell on the institution, literally overnight.” (JR)

Some respondents stated that this crisis was unpredictable; they felt that it constrained and changed the course of events, organizational models, and practices, as following:

“A crisis is always something that can condition it, so it’s always in the negative aspect. The crisis always changes the course of events, changes the organizational models and changes practices, therefore, changes the regular functioning of the institutions, forces us to, in a very short period, reformulate everything and get out of the box, so we cannot be in a functionalist structure, we have to rethink all the strategies, all the organizational models, the practices, the intervention models and adapt them to the moment of the crisis.” (JB)

Types of crises

Although crises can arise in infinite sizes, shapes, and magnitudes, concerning the types of crises, there is no agreement on the universal classification of crisis events (Devlin, 2007; Marcus & Goodman, 1991; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993; Spillan & Crandall, 2002). Some respondents mentioned unpredictable, health/diseases/pandemics crisis, economic and financial crisis, and political crisis as the types of crises faced by NPOs. Others referred to catastrophes, disasters, and sabotages. Some examples are presented here:

“We have an unpredictable crisis, and it is catastrophes, disasters, sabotages and other things that can happen.” (CR)

“Financial crisis, health or public health crisis (…).” (AG)

“The types of crises that can negatively impact a nonprofit organization are those of a political dimension, an economic-financial dimension and a disease dimension.” (JB)

Critical issues before and at the beginning of Covid-19

Regarding previous critical issues, it is important to remember that issue management represents a valuable proactive method of potential threat analysis, understanding external issues potentially affecting the organization and its stakeholders (Coombs, 2012; Mitroff, 1994 cit. in Jordan et al., 2016). For the respondents of this study, previous critical issues are related to low economic capacity and scarce financial resources, high dependence on the supervisory entity, establishment of partnerships with support institutions and networking, lack of equipment and human resources, unemployment, demographic aging, and changes, as well as ignorance and devaluation of risk and planning. Some interviewees clearly highlighted this:

“Critical issues before this?… any situation that affects the well-being of the population… unemployment, of course, but has to do with a financial crisis. There is an aspect that harms us immensely, which is the desertification of the interior, the demographic issue (…). The lack of revenue, of course, is reflected in the financial health of the institution.” (AG)

“(…) in an initial phase, there was a sharp devaluation of risk, perhaps associated with ignorance.” (JB)

“(…) we are doing what the social security institute asks us to do.” (CR)

“(…) we can solve or help to solve because the institution alone does not solve the problem.” “We have partnerships (…).” (AC)

“We have a series of partnerships (City Council, Fire Department, Civil Protection, Social Security, Health Delegate) that in such situations, they are always available.” (PA)

Also, respondents mentioned that at the beginning of the crisis, they were exposed to public opinion; attacks on the institution’s good name and reputation arose, depending on the goodwill of employees, confirming that NPOs are extremely vulnerable in times of crises (Sisco, 2012). Literature suggests that the more an organization is held responsible for the crisis, the more accommodative a reputation repair strategy must be, to protect the NPOs’ reputation (Coombs & Holladay, 1996).

“But right now, everyone is looking at institutions.” “(…) some attacks that we have been feeling that jeopardize our ability as managers and even as an organization, to deal with this.” (JR)

“(…) we are not omnipotent, and we do not have infinite resources.” “Human resources are never enough. But we tried to manage (…) we formed two teams to work in a mirror regime (…) and we managed to articulate all these people. Of course, it depends on their goodwill.” (AC)

Level of preparedness for the crisis

Concerning emergency preparedness, crisis management involves four interrelated factors: prevention, preparation, response, and revision (Coombs, 2015, cit. in Coombs & Laufer, 2018). All respondents stated that they were not prepared at all; no one could plan for a pandemic crisis like Covid-19, given its size and seriousness. Interviewees stated that clearly:

“Predict a situation like this, with this magnitude? Nobody is prepared for a hurricane. (…) What is normally required, we try to comply and try to have minimally legal things.” (PA)

“Nowhere, a situation like this was predicted (…) it never crossed my mind, going through the situation I had (…) in March, I had very bad days! (…). Before Covid-19, we had no plans.” (AG)

“We were neither prepared nor mentalized.” (AC)

Reasons for the lack of preparation and planning

According to Pearson and Mitroff (1993), the preparation/prevention stage includes the creation of a crisis team as well as crisis training and simulation exercises. In this study, interviewees point out the following reasons for the lack of preparation and planning: issues of leadership, non-professional management, lack of human resources, insufficient training in management and planning, as well as historical reasons, among other reasons.

“Have I delegated the technical staff responsible for each valence (…) to specify it in detail? What are the steps? It doesn’t pass me by.” (PA)

“We have “big ships” coping with non-professional management for years. (…) We had contingency plans; we followed the guidelines that came from different public institutions. (…) We had some human resources that allowed us to organize, creating offices/teams.” (JR)

“We are talking about structures that have an administrative and bureaucratic system that is often very slow, which obeys very strict criteria that are framed in specific legislation. (…) There is also a devaluation of planning, on one hand, and on the other, there is little training and awareness in the areas of planning. (…) NPOs do not think like market companies (…) are dependent on subsidies and state funding. (…) They are controlled by the State that gives NPOs guidance. Not receiving guidelines, these structures consider that there are no reasons to do so, they are not obliged to do so, and therefore, they do not do it. (…) structures that work a lot from volunteering and with people’s solidarity. (…) People have no training in management and planning.” (JB)

Crisis phase (response)

In this phase, the purpose is the “damage containment, is to limit the effects” with detailed plains for preventing a localized crisis from affecting other uncontaminated parts of the organization through an evacuation plan, procedures, mechanisms, or activities (Pearson & Mitroff, 1993, p. 53).

Reactive or proactive actions and contingency planning practices

Spillan and Crandall (2002) and Spillan (2003) state that there are two ways to observe a crisis: ignore the signals and react to the crisis, or prepare to prevent or manage a crisis. As an accomplished result, it is possible to confirm that the NPOs, of this sample, tend to respond and react to the crisis events, simply following the guidelines of official bodies, and creating contingency plans oriented by these entities. The following sentences demonstrate this:

“It was reactive in the sense that we were reacting, we started adapting what were the guidelines that were left by the official and public organisms.” (JR)

“We are going to react a little to situations.” (CR)

“The structures are reactive and not proactive.” (JB)

Procedures and activities of crisis management planning and prevention

As for this phase, the respondents mentioned that there is a need to create entry and exit circuits, operationalize mirror teams, reintroduce hygienic-sanitary practices, implement internal and external communication teams and offices, create segmented routing, reception, and transport protocols, list and prepare different volunteer platforms (of health care, and support staff) along with recruitment mechanisms and partnerships to provide emergency human force.

“Regardless of the contact with the family and communication with the population in general, it must be well defined who does this, how they do it, what information should be conveyed and how often, in each type of crisis.” (JR)

“Updated phone book”; “signage”; “routines”; “mirror teams.” (PA)

“Complaints management”; “A specific plan for each social facility.” (CR)

Conclusions and Future Research

In summary, the data collected, and here discussed, echo a reality, though partially true, shared by researchers who focus on the subject under study. Despite the exploratory nature of these results, most of the arguments of recent literature are confirmed.

Pre-crisis activities were suggested, namely: a plan for each social facility, the preparation of different crisis teams and offices (e.g., internal, external, digital communication, recruitment, and voluntary). It must be well defined who does what, how it is done, what information should be conveyed, and how often. Other processes should be in practice in a continuous way, such as systems of alert and trend awareness for a proper risk evaluation. For the crisis preparation, specific plans should include complaints management mechanisms, in and outflows, alternative teams, reception, routing and transport protocols, proper signage, routines, and the reintroduction of hygienic practices.

Specifically, for the pre-crisis phase, future research suggests two fundamental areas: risk assessment, diagnosing crises’ vulnerabilities, and crisis management plans as a primary tool for crisis managers (Coombs & Laufer, 2018). The lack of preparedness can be further analyzed in what reasons and explanation mechanisms concerns. Further research could, also, confront leadership perspectives with the perception of the technical staff and its operational lenses, as they have a fundamental role to play and are immersed in each specific context.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

References

- Caponigro, J. R. (2000) The crisis counselor: a step-by-step guide to managing a business crisis. Lincolnwood, Chicago, Ill.: Contemporary Books.

- Coombs, W. T. (2012) Ongoing crisis communication: planning, managing, and responding. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE.

- Coombs, W. T. and Holladay, S. (1996) ‘Communication and Attributions in a Crisis: An Experimental Study in Crisis Communication.’, Journal of Public Relations Research, 8, pp. 279–295.

- Coombs, W. T. and Laufer, D. (2018) ‘Global Crisis Management – Current Research and Future Directions’, Journal of International Management. Elsevier Inc., 24(3), pp. 199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.intman.2017.12.003.

- Crandall, W. R., Parnell, J. A. and Spillan, J. E. (2014) Crisis Management – Leading in the new strategy landscape. 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Creswell, J. (2003) Research Design – Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2nd edn. Sage publications.

- Devlin, E. (2007) Crisis Management Planning and Execution. Edited by A. Publications. New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Eriksson, K. and McConnell, A. (2011) ‘Contingency planning for crisis management: Recipe for success or political fantasy?’, Policy and Society. Taylor & Francis, 30(2), pp. 89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2011.03.004.

- Hermann, C. F. (1963) ‘Some Consequences of Crisis Which Limit the Viability of Organizations’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 8, pp. 61–82.

- Jordan, T. A., Upright, P. and Tice-Owens, K. (2016) ‘Crisis Management in Nonprofit Organizations: A Case Study of Crisis Communication and Planning’, Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership, 6(2). doi: 10.18666/JNEL-2016-V6-I2-6996.

- Kapucu, N. (2007) ‘Non-profit response to catastrophic disasters’, Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd., 16(4), pp. 551–561. doi: 10.1108/09653560710817039.

- Marcus, A. A. and Goodman, R. S. (1991) ‘Victims and Shareholders: The Dilemmas of Presenting Corporate Policy during a Crisis’, Academy of Management Journal. The Academy of Management, 34(2), pp. 281–305. doi: 10.2307/256443.

- Mendes, A. M. and Pereira, F. C. (2006) Crises: de Ameaças a Oportunidades – Gestão Estratégica de Comunicação de Crises. 1a. Edited by E. Sílabo. Lisboa.

- Meyers, G. C. and Holusha, J. (1986) When it hits the fan: managing the nine crises of business. Houghton Mifflin.

- Mitroff, I. I. and Anagnos, G. (2001) Managing Crises before They Happen: What Every Executive and Manager Needs to Know about Crisis Management. New York: AMACOM.

- Pauchant, T. C., Mitroff, I. I. and Ventolo, G. F. (1992) ‘The dial tone does not come from God! how a crisis can challenge dangerous strategic assumptions made about high technologies: the case of the hinsdale telecommunication outage’, Academy of Management Perspectives. The Academy of Management, 6(3), pp. 66– 79. doi: 10.5465/ame.1992.4274193.

- Pearson, C. M. and Mitroff, I. I. (1993) ‘From Crisis Prone to Crisis Prepared: A Framework for Crisis Management’, The Executive. Academy of Management, pp. 48–59. doi: 10.2307/4165107.

- Salamon, L. M. and Anheier, H. K. (1992) ‘In search of the non-profit sector. I: The question of definitions’, Voluntas. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 3(2), pp. 125–151. doi: 10.1007/BF01397770.

- Schwarz, A. and Pforr, F. (2011) ‘The crisis communication preparedness of nonprofit organizations: The case of German interest groups’, Public Relations Review. JAI, 37(1), pp. 68–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.10.002.

- Sisco, H. F. (2012) ‘Nonprofit in Crisis: An Examination of the Applicability of Situational Crisis Communication Theory’, Journal of Public Relations Research. Taylor & Francis Group, 24(1), pp. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2011.582207.

- Spillan, J. E. (2003) ‘An Exploratory Model for Evaluating Crisis Events and Managers’ Concerns in Non-Profit Organisations’, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 11(4), pp. 160–169. doi: 10.1111/j.0966-0879.2003.01104002.x.

- Spillan, J. E. and Crandall, W. (2002) ‘Crisis Planning in the Nonprofit Sector: Should We Plan for Something Bad If It May Not Occur?’, Southern Business Review.

- Ulmer, R. R. (2001) ‘Effective Crisis Management through Established Stakeholder Relationships’, Management Communication Quarterly. Sage PublicationsSage CA: Thousand Oaks, CA, 14(4), pp. 590–615. doi: 10.1177/0893318901144003.

- Waters, R. D. (2014) Public relations in the nonprofit sector: Theory and practice. Taylor and Francis Inc. doi: 10.4324/9781315758688.

- Wrigley, B. J., Salmon, C. T. and Park, H. S. (2003) ‘Crisis management planning and the threat of bioterrorism’, Public Relations Review. JAI, 29(3), pp. 281–290. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(03)00044-4.

Appendix – Interviews Script

Introductory note: in this phase, the focus is on the pre-crisis moment of, for example, a year ago.

- What are, in your opinion, the critical themes of crisis prevention in Non-profit Organizations? (Why? Can you develop that idea? Which type of crisis do you consider?)

- Regarding, specifically, the COVID19 pandemic, what was the degree of planning in your institution to deal with such a crisis?

- What are the reasons for this situation in your institution?

- What are the reasons that justify the possible shortage of planning in Portuguese NPOs? Can you talk about other cases or institutions you know?

- What activities, in your opinion, should be included in a crisis plan in these institutions?

- Can you add any supplementary comment that has not been discussed here?

Sources: Based on field experience and several studies (e. g. Smith, 2012; Waters, 2014)