Abstract

Established in 2019, the Roundtable on Black Men and Black Women in STEM convenes a broad array of stakeholders that focus on the barriers and opportunities encountered by Black men and Black women as they navigate the pathways from K-12 and postsecondary education to careers in science, engineering, and medicine. Through meetings, public workshops, and publications, the Roundtable advances discussions that raise awareness and/or highlight promising practices for increasing the representation, retention, and inclusiveness of Black men and Black women in STEM. In keeping with the charge of the Roundtable, Roundtable leadership and leaders of the COVID-19 action group conducted an informational video in January 2021 to provide an in-depth discussion around common, justified questions in the Black community pertaining to the COVID-19 vaccine. The manuscript addresses selected questions and answers relating to the different types of COVID-19 vaccines and their development, administration, and effectiveness. Discussion focuses on addressing vaccine misconceptions, misinformation, mistrust, and hesitancy; challenges in prioritizing vaccinations in diverse populations and communities; dealing with racism in medicine and public health; optimizing communication and health education; and offering practical strategies and recommendations for improving vaccine acceptance by clinicians, health care workers, and the Black community. This manuscript summarizes the content in the YouTube video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wdEC9c48A_k).

Similar content being viewed by others

Webinar Introduction

Dr. Cato Laurencin—Welcome to this special webinar of the Roundtable on Black Men and Black Women in Science, Engineering and Medicine (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wdEC9c48A_k). I am Dr. Cato Laurencin and we are here to discuss COVID-19 and vaccines, and questions of particular importance to the Black community.

I chair the National Academy of Science’s Roundtable on Black Men and Black Women in Science, Engineering and Medicine. The roundtable consists of almost 40 leaders from medicine, engineering, science, industry and philanthropy. We started the roundtable over a year ago to tackle the difficult issues facing Black people in science, engineering and medicine. Our vision was to create a trusted source for the Black community, and for the world, on a range of issues affecting Black people.

The roundtable has been hard at work, and has addressed issues ranging from racism in academics, the COVID-19 pandemic and Black people, and the educational pipeline for Blacks from pre-K to graduate education. Our goal here is to provide reliable information on the COVID-19 vaccine. This webinar is particularly directed to the Black community, which has long had very justified questions of trust in medicine and in the medical enterprise [1].

Four distinguished members of the roundtable join me. They are leaders who have worked at the forefront of issues facing Blacks in medicine, science and engineering. Let me introduce them to you.

I am Dr. Cato Laurencin, Ph.D, M.D. I am the University Professor and Albert and Wilda Van Dusen Distinguished Endowed Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Connecticut. I am the Chief Executive Officer of the Connecticut Convergence Institute at UConn. I am an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine and an elected member of the National Academy of Engineering.

Dr. Hannah Valantine, M.D., is our moderator for this webinar. She is Professor of Medicine at Stanford University and she served as the first NIH Chief Officer of Scientific Workforce Diversity. She is an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine.

Dr. Cedric Bright, M.D., is Professor of Internal Medicine and the Associate Dean for Admissions and Interim Associate Dean for Diversity and Inclusion at the Brody School of Medicine in Greenville, North Carolina. He served as the 112th President of the National Medical Association.

Dr. Camara Phyllis Jones, MPH., Ph.D., M.D., just completed her tenure as the 2019-2020 Evelyn Green Davis Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. She is a past President of the American Public Health Association, Adjunct Professor at the Rollins School of Public Health in the Department of Epidemiology and the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, and an Adjunct Associate Professor and Senior Fellow in the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at the Morehouse School of Medicine.

Finally, Dr. Clyde Yancy, M.D., MSc, is the Magerstadt Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and Professor of Medical Social Sciences. He is the Chief of Cardiology Medicine at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. He is an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine and American Association of Physicians.

We believe that Black people should proceed and receive the COVID-19 vaccine. We all have. We understand, however, there are important questions to address. We are here to provide pertinent answers. We will start with the video.

Now at this point, I would like to turn over the webinar to Dr. Hannah Valantine.

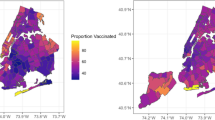

Webinar

Dr. Hannah Valantine—Thank you very much. I would like to take a moment to share the context of why I am personally excited and committed to doing this webinar with the National Academies and my colleagues. Early state vaccination data have raised warning flags for racial equity. As of January 2021, vaccination patterns by race and ethnicity appear to be at odds with who the virus has affected the most [2]. Based on vaccinations with known race/ethnicity data, the share of vaccinations among Black people is smaller than their share of cases in all of the 16 reporting states, and smaller than their share of deaths in 15 states [2].

For example, in Mississippi, Black people account for 15% of the vaccinations, compared to 38% of COVID-19 cases and 42% of deaths [3]. In Delaware, Black people have received 8% of the vaccinations, while they make up nearly a quarter of cases, 24% of deaths [2]. Similarly, Hispanic people account for a smaller share of vaccinations compared to their share of cases and deaths.

Together, these data raise early warning flags about potential racial disparities in access to and uptake of the vaccine. Now, as members of the National Academies roundtable addressing health and biomedical issues for African-Americans, we are here as a group of physicians and scientists to answer some of the many questions that are being asked by our community.

I would like to ask a particular question that I have heard: what is the ground truth about the COVID-19 vaccination? Does it work? In minority populations, in racial ethnic groups, what really is the evidence that it works, is it effective at preventing us from getting this devastating disease? To answer that, I have asked Dr. Yancy, who was already introduced to you, to really walk us through what do we actually know. What is the truth around vaccine efficacy?

Dr. Clyde Yancy—I am delighted to be a part of this webinar, and I am delighted to address the question of what we know about the vaccine in Blacks. I would like to first, continue a theme that my colleagues, Dr. Cato Laurencin and Dr. Hannah Valantine, started. My commitment to this question is strong; perhaps, the most egregious evidence of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Blacks has emanated from my current home city of Chicago, and from my former home city of New Orleans.

Black people have disproportionately suffered from this condition. Thus, it is important to participate in this webinar and convey information that might help reduce this burden going forward. An effective vaccine is part of the solution. The question however is whether it is effective in Blacks?

Within the last 12 months, we have seen the identification of the genetic code for the novel coronavirus, which is responsible for COVID-19. Nearly immediately thereafter, we witnessed the development of a vaccine, the animal and clinical trial testing and in less than a year, emergency use authorization from the FDA to deploy the vaccine. Those are nearly miraculous developments and highlight the power of science. Let me deconstruct this story. First, for those who believe the development was too fast and mistakes may have occurred due to haste, it was not quite as fast as you think. Dating to 2003, 2004, when we dealt with the MERS virus and the first SARS virus, it became evident to the public health community that we were likely going to face a virus that would have outsized pandemic-level impacts. Those concerns were prophetic.

In 2013, several labs, working under the auspices of the NIH, started exploring novel ways to develop anti-viral vaccines; what emerged was a new target: viral RNA. One of the vaccine companies is Moderna. That name purportedly comes from “modern RNA”, meaning the modern way to make a vaccine is by targeting the RNA.

This powerful platform was used to target a vaccine against Ebola as soon as the science community heard about the virus outbreak in China, and especially once the genetic code was available, this new platform underwent a dramatic pivot with the new focus on Coronavirus. Here is a startling observation. This new platform of discovery was so potent that the first copy of a vaccine against Coronavirus occurred eight days before the first case appeared in the United States. That is truly a remarkable application of breakthrough science.

I hope the story of discovery will highlight Kizzmekia Corbett. This is an emerging star African-American scientist, a woman working in the Graham lab who once equipped with the genetic code for the novel Coronavirus, developed an early iteration of the vaccine [4].

Figure 1, taken from FP Polack et al., describes the efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine against Covid-19 after the First Dose [5]. The graph represents clinical trial participants who received placebo (blue line) or the vaccine (BNT162b2, red line). The blue line represents the control population and the incidence rate of COVID-19. The red line represents the treated or vaccinated population. This abrupt change between placebo and vaccine, i.e., an inflection point, is unheralded and emphatic proof of effectiveness. This is why we can say with conviction that these vaccines are 95% effective, given the striking decrease in the likelihood of developing COVID-19.

Efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine (BNT162b2) against COVID-19 after the first dose. Data shown represents the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 after the first dose. Blue line represents individuals who received placebo. Red line indicates individuals that received the vaccine (BNT162b2) [5]

What about Blacks uniquely? Were we included in these studies, and how did this vaccine work in us? The first question is, yes, we were included. Black or African-American represented 9% of the people in this 30,000-patient trial (Table 1) [5].

That 9% is amongst the best representation that we see in any trials or test of a new therapeutic medicine. This threshold of participation approximates the representation in the population of ~ 12 or 13. The 9% representation in this trial is two-fold higher than we usually see in any trial. I applaud the investigators for making an overt effort to recruit Black people into the study. Without any equivocation, I can say with certainty these data are inclusive of Blacks.

Given the representativeness of Blacks in the trial, the next question is effectiveness. In Table 2 of this pivotal publication, we see the data according to participant profiles including race. The data field of reference here shows “zero”. That means, in the Blacks that received vaccine, no Black person developed COVID-19. The percent success was 100% successful. The vaccine works in Blacks.

Now, to be fair, the results seen in a carefully performed clinical trial may not fully replicate in clinical practice. But we can at least say with conviction that, in this study, 1) Blacks were included, 2) the response in Blacks was at least as good as everyone else, and may have been amongst the best response and 3) overall, for everyone in the trial and for all of us in the community, this vaccine worked.

How it will work long-term, those are questions remain unknown. How it will work against the new variations of the novel coronavirus, COVID-19? We believe it will continue to work, but this will take further study. For now, vaccination is the best tool we have to attenuate what has been a devastating effect of COVID-19 on the Black community.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—Thank you for that compelling and encouraging presentation. However, we know a lot about science. We know a lot about these research studies that promise so much. On the other hand, we hear this continual turmoil and churn of the rumor mill about so many issues. For example, can the vaccine alter my own DNA? Can the vaccine alter my fertility? Can someone get COVID-19 from the vaccine itself? I am going to ask Dr. Cato Laurencin to address those kind of rumor mill issues that continue to bother everyone, including people in our Black community.

Dr. Cato Laurencin—I want to just underscore the fact that this is historic. We have a vaccine that had Black scientists involved in development. We have had a clinical trial. I sat on the Science Board for the FDA, and constantly talked about the fact that we have clinical trials that are geared toward Black people that had no Black people in them. In this clinical trial, we have substantial numbers of Black people [5].

We have established a body, the Roundtable on Black Men and Black Women in Science, Engineering and Medicine. This is a standing body that can stop and review data and information, as well as impartially look at the scientific and clinical information presented. We have all heard the many rumors about the vaccine. One question in particular, can the vaccine alter my own DNA? The answer is no. Some patients have also asked me, can I get COVID-19 from the vaccine itself? The answer is no. Another rumor is could the vaccine alter my fertility. The answer is, at least as far as we know, no. Clinical trials found no difference in fertility with people who got the vaccine and those who got placebo [6]. Part of the reason why we are here is to dispel the rumors in these different areas. As far as we know, and as far as the information that we have gotten from the clinical trials, these are rumors, and we can dispel them with our comments today.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—Thank you. Would anyone else want to chime in on these rumor mills and misinformation?

Dr. Clyde Yancy—Dr. Valantine, it is not a rumor mill, these are real concerns that our people articulate. We need to listen. Recently I have been going from one morning huddle to the next in my own hospital. Listening to Central Supply teams, Loading Dock crews, Administrative technicians, and food service staff—the questions echo. Is the vaccine safe? What are the side effects? Will it work in me? Despite the research that I lead and the leadership profile I have, our own data tell us that, amongst the 33,000 vaccinations we have given to health care workers in our large health care system, employees of color subscribe to vaccination at a 30% rate, far below all other essential health care workers in our hospital. Remarkably, my own teams have expressed the greatest ambivalence and do not believe this is appropriate. Clearly, we have a trust issue.

In addition, the questions are quite appropriate. Why does it require two shots? Why does it hurt? How long will it last? What about the new viruses that I am hearing about? The vaccine developed too fast; how did that happen? In addition, what will happen to me two or three years from now?

An important lesson learned, never discount the question of anybody, and answer with honesty. The more who are engaged in these conversations, the better. I had my clinic today; one of the persons, who was in one of these huddles, came to the clinic with mask on and said, “thank you for helping me understand what is involved. No one had spoken to us. No one had educated us. No one wanted us to know what was going on. They just said go take the vaccine. We do not want people telling us to do things without telling us why”. It is not a rumor mill; rather it is an explanation of why behaviors are as they are.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—That is fantastic. Thank you for emphasizing that, Dr. Yancy. People are concerned because they do not have answers. I find that, when people do not have answers, they fill in the blanks themselves. This is why we are here, as a trusted voice to be able to explain and answer the questions.

Dr. Camara Jones—I agree entirely with Dr. Yancy that it is not on us to coax, convince, or cajole people into taking the vaccine. We need to hear people’s questions and answer them. The evidence on the vaccines that we have so far is so compelling. The vaccine is effective and everything that we know about the safety profile says that it is safe.

We want people to ask their questions. Right now, we have questions that we are going to answer, but there will be other questions that arise as the vaccines are rolled out, as the virus potentially changes. It would be good for people, when they have questions, to have a source who can answer those questions. If you have a primary care physician or pharmacist, ask that person first. The worst thing to do would be to hear something and, rather than getting information, spread a rumor that might discourage other people from asking their questions or taking the vaccine. We do not want to be spreading rumors. We want to have our questions, because our questions are important, and we need to get them answered. Is there any recommendation from you all about, especially if people do not have a primary care physician, how they should approach getting answers? They can look online, and hopefully, the information will be accurate, but maybe it will not be. So where should people go?

Dr. Hannah Valantine—This is a great question. I do think that the educational piece that you raise is important. To what extent are our primary physicians conversant with this kind of information? I hope that this webinar will be disseminated to other physicians so that they can answer the questions. Now, the issue of where to go is a good one. Going on different websites does not necessarily give you the correct answer. There is a lot of stuff out there that is incorrect.

Dr. Cato Laurencin—The CDC website is a good source of information [7]. A study by the Pew Foundation, spoke to the fact that Blacks are very adherent to a number of the guidelines as set forward by the CDC. Blacks are very intelligent about these issues, adhere to guidelines of CDC, are curious about the facts, and are curious about the data. The questions reflect a high not a low level of understanding of issues. The CDC website is a good central trusted source for information that I would recommend.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—I would also support the CDC and things that come out of trusted sources based on science, not on opinion.

Dr. Camara Jones—The surveys that indicate that there is some vaccine hesitancy in Black communities, for example, the Kaiser Family Foundation, indicated that 35% of Black folks were not sure they would take the vaccine right away [8]. In that same survey, 42% of Republicans and rural people said the same [8]. Yet, you do not hear the news pounding so much on Republican or rural vaccine hesitancy. Clearly, Blacks do have a justified skepticism because, in our history, there are so many things that have been done to us and upon us. But I do not think that we should glorify vaccine hesitancy in the Black community; we should meet it and answer the questions.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—Absolutely. While you’re on the floor, Dr. Jones, there is one particular issue that I would like you to comment on, which is a question that I hear often. After I have been fully vaccinated, do I really have to keep wearing my mask and social distancing?

Dr. Camara Jones—The simple answer is yes. Yes, we all need to be wearing our masks, social distancing, handwashing, as well as avoiding contact with people outside our household until the pandemic is well controlled. There are many reasons for this. First, these amazing vaccines, these mRNA vaccines manufactured by Pfizer and by Moderna, are 95% effective. That means, even if you are fully vaccinated, there is an off chance that you still can be infected. The bigger question is, can you pass it on to someone else? These clinical trials were not set up to answer that question. Not yet. Therefore, it is possible that the vaccines keep you from having symptoms, from going into the hospital, and from dying, but they may not keep you from having enough infection in your nose and in your mouth that, if you were to speak, cough or sneeze, someone else could get infected. Wearing a mask is not primarily to protect us. It is to protect those around us. The virus is spreading quickly, and every time it spreads from one person to another, it can mutate to become a different variant. As far as we know, the vaccines that are out there right now do protect against the variants that are out there right now. But as long as this pandemic is raging, as long as the spread continues, there will be more variants.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—I want to underscore one point that you made, which is causing a little bit of worry in the community, is these new strains, and will the vaccine be effective on these new strains. From what we see, the answer is yes. Another important question frequently asked, is I have had COVID-19, should I get a vaccine? How long should I wait to get the vaccine after I have been infected? Dr. Bright will help us tackle that question.

Dr. Cedric Bright—This is a great question, the data suggest that people get the vaccine after they have had COVID. We do not know how long the antibodies from the actual infection last in the body, but we do think that it does confer some type of immunity for at least up to 90 days. We are suggesting at that particular point, within 90 days of the COVID infection, somebody should consider receiving the vaccines. That is the recommendation at this particular time.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—Are you finding your patients are asking you that kind of question?

Dr. Cedric Bright—Yes, it is a tough question, but more importantly, it is a fair question. I think that we need to be able to hear these questions and ask to understand where the questions are coming from, and to validate the concerns of the people that raise these questions. Most importantly, find an answer. If we do not know an answer, let us be honest about that and say we do not know the answer but we are still researching it, and we may find out soon.

Dr. Clyde Yancy—Dr. Valantine, if I may, Dr. Bright brings up a very important point. If you think about why we are having this conversation, yes- we are trying to save lives, but we are also trying to restore our life and living circumstances. The past year, 2020, profoundly affected every aspect of life. Only with protection from COVID19 will we once again converse, travel, and congregate freely. We need the majority of the population protected from COVID-19, otherwise known as “herd immunity”. There are only two ways that can happen: Either active immunity, which, for our lay audience, means you have had COVID-19 and your own natural defenses have developed an antibody response or passive immunity because you received the vaccine and the vaccine has generated an antibody response. When we add the two together, it needs to get to about 65% or 70%. Protecting the “herd” requires we meet those thresholds.

If we get to that level, can we relax? When can we go to church again? When can we go to Friday night football again? When can we have a picnic again? When can we get rid of the mask, (probably not soon with the mask)? Getting together safely for any reason and at any size means we achieved herd immunity. The vaccine plus sound public health preventive measures restores life and living as we once knew it.

By the way, note that I did not call it normal because, for Black people, what we were experiencing was normative but not normal. We need to move towards a new normal.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—Excellent point. For a related question, how long will the vaccine effects last? When can we, and for how long can we, feel comfortable doing exactly the things that you just listed, Dr. Yancy?

Dr. Clyde Yancy—Soon. We can do this. Even if it requires annual vaccination, we know how to make that happen-see annual flu vaccination. No one even blinks an eye. We wait for the new vaccine to come, we go to the local drugstore, and we get the immunization. So what if it only lasts a year? If that is what it takes to bring this down to some quieter level, so be it. Science has provided us a powerful tool. We now have a platform to develop vaccines in an iterative, as needed way. Yes, we can do this.

Dr. Cedric Bright—I agree with Dr. Yancy. The other part of that, though, is the model of the hepatitis vaccine for which we get a booster. We got three different shots for the hepatitis vaccine, and that confers an immunity for a lifetime. We are still new with the vaccine technology, and we do not know whether this is going to give us a lifetime immunity or this will be a seasonal phenomenon. Certainly as we continue to have variants, if the variants become more powerful such that the vaccine does not cover it, we would have to create new renditions of the vaccine covering new variants, exactly what we would do with the flu every year. Every year, we change different valence parts on the flu vaccine in order to meet what we think is going to be the strain of the flu. We already have a custom in place where we are used to getting vaccinations for these types of things, such as influenza. This will most likely become the norm in the future and it will be just a yearly vaccine as the flu vaccine is today.

Dr. Cato Laurencin—Let me just add one thing. When we think about the seasonal flu, there is a seasonal flu. The season for COVID is 365 days of the year. I completely agree, I do believe that we will need to have either a booster, or some sort of new vaccine on a yearly basis, because this is not your average virus that we are facing. It is also very important that we get ahead of this in terms of the Black community. We have had this situation before, in terms of HIV, where now, every year, 45% of individuals with the HIV virus are from the Black community [9, 10]. We need to make sure that we get ahead of this because we do not want this to become something that is centered in the Black community in terms of the future.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—I could not agree more, that is why we are all here, and why we are all extremely concerned. We must not let our brothers and sisters get left behind in this one.

Dr. Camara Jones—There are just a few points that I want to pick up. The first, Dr. Yancy, you talked about two ways to get immunity, either get COVID or get the vaccine. Getting COVID is a much worse way to get immunity. I just want to say that if you get COVID, you might die. However, even if you do not die and you recover, you may not fully recover. Many people have reported being tired and having brain fog. We do not know what the long-term side effects of having gone through a COVID infection and surviving are. The best way to get immunity is to get the vaccine. The other point is about herd immunity, as Dr. Yancy said, and the early estimates were that 65% to 70% of the population would need to be immune to achieve herd immunity. That number is estimated based on how easy it is for the virus to go from one person to another and how long it takes to double, the doubling time. When you get these other variants that are more infectious, easier to spread, it means that a higher percent of the population is going to have to be immune before we achieve herd immunity.

Herd immunity means that if there is an individual who cannot get the vaccine and that individual is surrounded by people who are already immune then the virus cannot get through to that individual. Our estimates of the percent of the population that needs to be immune to achieve herd immunity are increasing as the new variants are becoming more and more infectious. The other thing is that, even if we get things under control in the US, this is a global pandemic. We have to be concerned about what is happening in other parts of the world. Lastly, I believe that the primary reason Black people are not getting as much vaccine as others in the population, when we really should be getting an even a greater percent to match the levels at which we are getting infected and dying, is not because we’re refusing it, but because the vaccine is not being put in our communities in ways that we can get it. The primary reason is also due to the phasing that the CDC proposed, where the first phase was health care workers and nursing home residents and the second phase was supposed to be other essential workers. Many states added those aged 65 years and up to the first phase instead of moving on to essential workers who are more exposed because of their work environments.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—You have addressed a couple of upcoming questions, firstly to do with the individual who cannot take the vaccine or decides not to, and then the issue of will it actually end this pandemic, which has implications for the pandemic outside of this country. There are people who, for medical reasons or for personal reasons cannot be vaccinated. So how else can they protect themselves?

Dr. Cedric Bright—There is really only three ways to protect yourself. That is the three W’s. You have to wash your hands, you have to wear a mask, and you have to socially distance. You have to wait your distance. Those are the three best preventive health mechanisms that we can practice to mitigate the spread of the virus, if you do not get the vaccine. If there is a reason for why I cannot get the vaccine, those are the three measures that I’m going to continue to implement, as well as stay home and shelter if possible. That is so difficult for so many people, and for so many reasons.

Dr. Cato Laurencin—If someone decides not to get the vaccine for any reason, they have to double down on these things. There are other areas that I would like to add such as being physically fit is important. Having the good nutrition, if one smokes, stop smoking, because we know the damage that can take place with COVID-19 and the lungs. Individuals have to keep themselves as healthy as possible in terms of your life.

Dr. Cedric Bright—Let me just add one more point; what Dr. Laurencin is talking about is a shift in our thinking about what health is. There are seemingly two paradigms of health. There is the reactive health that we have when we’re healthy until something happens and it stops us from doing what we do, and then we access the health care system, and then there’s the preventive health, which is we have our health, we want to maintain it, and so we do everything we can to do so. I believe that this vaccine gives us an opportunity to shift our paradigm and be more proactive about our health in our Black community. That is why I think it is important for us to take this vaccine.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—That is a profound statement. Just to bring this part of this discussion to the end, I’d like Dr. Jones to comment on what you would say to a person asking you the question, will taking the vaccine end the pandemic? What do you say?

Dr. Camara Jones—Taking the vaccine will protect you as an individual, but for us to all end the pandemic, we have to also double down on the public health strategies. We need to support government efforts to cut down on the amount of virus that is being spread. That is the most important thing. We can protect ourselves with the vaccine, we can protect others by wearing the mask, and we can protect the whole country by making sure that we become politically active and reach out to our representatives to say that it has been too long that this pandemic has been ignored. The virus only has one job, and that is to replicate itself. As long as the virus can find somebody who is both available and susceptible somebody who is not protected and not vaccinated, it will keep spreading. It will burn through our population until it cannot find anybody else who is susceptible. We need to protect our own selves with the vaccine, and we need to protect our community by cutting down the spread. We limit the number of available people with our public health strategies. We limit the number of susceptible people with the vaccine. Many people cannot shelter in place, but they could if we, as a government, made it more feasible with periodic survival checks. And for those whose work is really essential, the government can ensure that workplaces are safe and that workers are fully protected with personal protective equipment and vaccination.

Dr. Clyde Yancy—There is another perspective in addition to that which Dr. Jones has just so brilliantly articulated. That is the evidence of how important an intact and responsive public health system is for the health of our country. Part of our dilemma was a fractured public health system that was slow to respond, and had no reserve capacity. Once again, dis-investment in a critical human service haunted us. As we focus on the vaccine, those of us who think about process recognize that it is not just the vaccine. We need to restore our public health enterprise with trust restored in our public health officials and a newly invigorated network of community clinics [11]. This is not the last pandemic that we will experience. The things that we can do to anticipate the next pandemic, the decisions that we know we need to make early, particularly affecting travel and distancing, should be permanently embedded in our mindset. Public health is our new priority.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—Most of us underestimated the importance for the need for a systematic approach. The devastation that has occurred in the recent past to public health needs to be restored. I would like to bring up the question about, what vaccines are available now. What are the vaccines? What are the range of COVID-19 vaccines available? Do they work differently? Do they work at all? Does the individual have a choice to which of these vaccines to take?

Dr. Cato Laurencin—In the U.S. right now there are two vaccines. There is the Pfizer vaccine and the Moderna vaccine and they are based upon mRNA technology. The mRNA segment is wrapped in a nanoparticle that is made of a fat or lipid and is taken up by the cells. The cells end up taking that mRNA and allowing proteins to be made. The proteins are recognized as a part of the virus, but it is not the virus itself. The body sees these protein particles and says let us attack it. The body attacks the protein particles on its own terms, without lots of virus particles replicating and doing a lot of damage. It does it on its own terms, and then creates the memory, where if it comes again, the body already has the cells and the factors to fight the virus.

AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson use a more traditional technology, where a virus called an adenovirus, which is very weak, has small segments of some DNA that codes for that type of the protein in the virus. The very weak virus is taken up by cells that produce the protein. Again, the body creates the memory. Where it is excreted the immune cells react to it, understand where it is, and then remembers it.

The Pfizer and the Moderna vaccines have about a 95% effectiveness [12]. Dr. Yancy met with us; we had our pre-meeting, in which he stated it was 100%, in terms of the study, that was there for Black people [5]. There was a lot of incredulity by Dr. Bright, who said show me the data, and of course which he says. That is why we opened with that data, which is great, because the specter, is always that these results, 95% effectiveness, can that apply to the Black community. Some of our data, the data that Dr. Yancy has shown says yes. The 95% level of effectiveness is a confident net level for the Black community.

The AstraZeneca and the Johnson & Johnson vaccines are coming out. It is not 100% clear where the efficacy level is. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine is a single shot vaccine; it may need a booster. Dr. Yancy, do you have any thoughts, any comments or thoughts?

Dr. Clyde Yancy—Recently, we learned that the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in the United States is about 60% to 70% effective, but importantly, it is 85% effective against the serious consequences of COVID-19 [13]. Consider this more good news. Any one of three vaccines will prevent you from having COVID-19 pneumonia, ICU level complications and/or death. You may feel flu-like symptoms, but you will not become desperately ill. This is all evolving as we speak but it is good news.

There are other vaccines, deployed in other countries, e.g., United Kingdom, Brazil, and China. Moreover, there are over 50 additional vaccines under development worldwide. Is this the path forward? We will have to see how this all evolves. Will we find easier vaccines to make, easier vaccines to scale up in production, vaccines that are longer-lasting, thinking about Dr. Bright’s comments earlier? These are the areas of the unknown.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—This is such an exciting discussion, especially around those new ideas of those new technologies, this messenger RNA, synthetic messenger RNA. I mean, all of us did biochemistry as we did medical school, and we learned about messenger RNA, which is essential for taking the message to the cells to make proteins. Scientists now can make synthetic ones that are specific and create messages to proteins and antibodies to protect all of us in these vaccines. All of this sounds costly, right? Think of the investment that has gone into this, and the companies. What does it cost, Dr. Yancy, to be vaccinated?

Dr. Clyde Yancy—For the end user receiving a vaccine, it is free. Free. This may be the most egalitarian initiative I have ever seen come out of our federal government/industry enterprise, (politics-agnostic). What will happen going forward? To what extent will taxpayers still feel that it is part of our responsibility to support this? I worry that this will evolve, and cost shifting may occur. For right now, it is free. I have had to answer that question repeatedly. This is another real question raised by everyday people struggling to feed and house their families. We must convey truth; the vaccine is free.

Dr. Cato Laurencin—If we look at individuals in terms of vaccine hesitancy, one of the top five questions is the cost. I think it is great that our country has taken that off the table, at least right now. The other questions are should I choose to get it, should I wait and get it, what vaccine, and do I have a choice. All the vaccines have gone through emergency use authorization. They all had a process by which, the ones that will be on the market, have had information and data that the FDA has decided that the benefits outweigh the risks. I believe that people should get whatever vaccine is available to them.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—Thank you. I was looking for a specific answer like that to this question because already, again, through the rumor mill, there are suggestions that one might be better than the other. I do not think that is the message we want to give. We want to say take what is available in your community and make sure you get vaccinated quickly. Get to the front of the line.

Dr. Cedric Bright—But to that point, if you get a Pfizer vaccine, we want you to follow up with a Pfizer vaccine. If you get a Moderna, we want you to follow up with a Moderna. However, if it gets to a point where you do not have that second Pfizer or that second Moderna, you can interchange and get the other one. It is not recommended, but it can work in that substitute manner.

Dr. Camara Jones—I also want to raise a question, though. The two vaccines that we have out here right now are extremely effective, and equally effective. When we start getting others, they might have different levels of effectiveness. Just knowing how things go down in this country, if some vaccines are thought to be less effective, those might be the ones that flood our communities, where right now the very effective vaccines are being disproportionately made available in the whiter communities. What do you all think about that?

Dr. Cedric Bright—We have a tremendous pattern of history that would suggest that could possibly be the case. That is why we have to be vigilant about advocating for our communities. That is what we do in our communities, we advocate for us. We put out forums such as this to educate others so that they can advocate. We need to continue to do that type of activities.

Dr. Cato Laurencin—I agree. I can tell you something, I have thought about the same thing. One of the things that my mother said, if you are Black and you do not have a healthy sense of paranoia, you have not been paying attention. Therefore, this is something that I have thought about, too. Again, this is something that we are watching, this is something I know this whole group is watching and looking at the disparities that may be created by the system and speaking out on it when we see it. This is a very important issue and question that we are all thinking about.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—What is the hope that there will be a prioritization for vaccination that takes into account this massively increased risk by race?

Dr. Camara Jones—That was already prescribed by the National Academies’ consensus study on a framework for the equitable allocation of vaccine against COVID-19 [14]. They said two things. There should be phasing, which the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the CDC adopted. But they never did pick up on the other important part, which is prioritization within each phase. For example if you’re looking at nursing homes but you don’t have enough vaccine for all nursing homes all at once, which nursing homes get at first? The NASEM committee said that we should be using a vulnerability index. We should be saying, who is the most needy? Who has been most impacted? The states, when they get their vaccine, should put the vaccine in those 25% most needy communities first. That has not been happening. Instead, in some places, it has almost been first come, first served. That is never going to be equitable when you talk about first come, first served because some people need to work. They cannot be on the computer all day, may not even have a computer or know how to get online. So I think that we as a nation have fallen down on equity, but we need to press, because providing resources according to need is one of the core things we need to do if we’re going to be about equity.

Dr. Cato Laurencin—I agree somewhat, but I do believe that we’ve got to get down to basics in terms of our community and encourage in terms of having Black people get the COVID-19 vaccine. We have also observed vaccine hesitancy in health professionals and people who are eligible, who are Black. It has been documented a number of times that people who are health professionals who have the access to the vaccine who are Black are getting the vaccine at a lower rate. It is a double-edged sword. A number of people have commented that Blacks should maybe even come first because of our higher rates. At the same time, many Black people would say, you want us to go first? Well, you go first this time. I think that just getting access, getting the Black people to have the questions discussed in a comfort level in terms of getting a vaccine will go a long way in terms of equity. I personally am not fighting to say Black people should be in the front of the line for vaccines. I just think that we should have our fair share and fair chance in terms of moving forward. We should be monitoring any adverse events that are taking place. I think if we do that and we are diligent about that, and make sure the vaccine is in our communities, that there are no waystations in which they’re not there, make sure it’s the most efficacious vaccines in our communities, I think that we can be successful.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—I personally would like to see that gap that I alluded to in the vaccine rate compared to the case rates and the death rates closed, or at least narrowed. You know, I think that is critically important. I do not know how to do that, but any opportunity I get, I am going to be advocating for that.

That gives a little bit and addresses the question many people ask, if we are living in a house with multiple generations, why can’t we all receive the vaccine at the same time? A related question, what is the difference between this vaccine and a flu shot?

Dr. Cedric Bright—We know that the COVID vaccine is an mRNA virus, whereas the flu vaccine is more of a polyvalent virus that is developed, and utilizes different technology. Often time, uses eggs or other type of embryonic tissues in order to develop the vaccine. The flu vaccine has a different constituency compared to the COVID vaccine.

Getting to your point about the multigenerational households, you know that African-Americans in the United States and Latinx Americans actually have more of a propensity to live in multigenerational households. That means it could be grandparents living with their children, and the children have kids, and so that is three generations. It could be a grandparent who is taking care of a younger adult because they have come back to escape issues of the city, or they are jobless because of the COVID situation. They brought kids with them, and so now, there is three generations. And so forth and so on.

The concern is, if you are identifying one group to be more vulnerable, such as the older population in a household but the younger generation may be more of a threat to the older person, it would seem that to mitigate the issues for the whole household, a vaccination of multigenerational people within the household should be considered. I do not know how much that has been discussed in the national platforms. Dr. Jones, you may know some more about this. It would seem to me that this was maybe something that was not thought about and has become more of an afterthought, even though we knew this was an issue with COVID’s outbreak.

Dr. Camara Jones—I actually think it is a great idea. I know that in Georgia, many of those 65-year-olds are able to also bring their caregivers to come get vaccinated with them. If that is happening in your state, then everybody living up in that house is a caregiver.

Dr. Cedric Bright—That is not happening in my state right now. In fact, we have people who are coming in from out of state and getting vaccinations in our state. How they are getting on the list, I have no idea, but that is what is happening. Those that have that ability will do it, especially when it comes to survival, because as we say, this is a real-life, true-life Hunger Games.

Webinar Concluding Remarks

Dr. Camara Jones—We have to use all the tools we have against COVID-19. The vaccine is a very good tool in our toolbox, and it is an important tool, but it is not the only tool. We need to also fully implement all of our public health strategies at both the individual and the government level. And we cannot let those people who are better positioned to game the system do that on our health and on our bodies.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—Dr. Bright, while we have you on the stage there, I want to take the discussion back as a sort of a wrap-up to addressing this mistrust, which is very justified, given the history in this country of medical various issues and malpractices on Blacks. How do we really address this issue of hesitancy in this community? We have talked a lot about approaches, but would you like to help summarize where we need to be going with this?

Dr. Cedric Bright—We need to employ the 4A model. The 4A model means to ask the question of the people, we need to acknowledge their answers, we need to address those answers, and then we need to affirm to them their validity to have those types of questions. Once we do that, we have to provide the information that dispels the misinformation. We need to find our trustworthy people to deliver that message such that the message will be trusted.

Dr. Cato Laurencin—Dr. Bright that was wonderful. I think there are short-term and long-term things that we can do. One of the short-term things is what we are currently doing. We have the roundtable; the goal of the roundtable is to create a group of trusted people and trusted voices in the community for many issues, COVID-19 is one of them. We also need to recognize that, because of racism and discrimination, we just do not have many Black doctors in America, and especially Black male doctors. That means that there is less trustworthiness in terms of the system. We also know from a number of studies that Black physicians are more likely to treat Black patients, in terms of administer care [15,16,17,18].

Now there are some interesting studies that have demonstrated in terms of infant mortality, cardiac care that Black physicians taking care of Black patients, the outcomes are better [19, 20]. We need to acknowledge that making changes to increase the number of Black physicians that are present in our healthcare system. This will help in terms of building trust in the system. We need to employ Black physicians in terms of talking to the Black community. We need Dr. Fauci to talk about issues in the minority communities. We need to look at our trusted sources in the Black community of physicians. We have the four people here that are some of the greatest clinicians and scientists in the world, so we need to rely on these trusted voices, and to bring those trusted voices out to be able to address the issues.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—COVID, with all of its devastating consequences, has shone a light on all of the issues that will, and should, galvanize the work that we are doing at the roundtable. The big challenge is getting our voices heard. We have great voices, we have some numbers, but we still need to find a way to disseminate and amplify this trusted voice that we have. This is what we have been talking about and we will be working on.

Dr. Camara Jones—We keep talking about how Blacks are getting infected, hospitalized, and dying more than other races/ethnicities. This is not just a happenstance. This is not because we are genetically different or more biologically vulnerable. We are more likely to become infected because we are more exposed and less protected. And once infected, we are more likely to die because we are more burdened by chronic diseases with less access to health care. All of that has racism at its roots. And this is not our last pandemic. If we do not deal with how racism structures the conditions of our lives, structures our opportunities and assigns value so that we are thought to be essential but disposable, if we do not address racism as a root cause, then when COVID-23 comes through, we are going to see the same disproportionate impact on Black communities.

Right now, we are talking about the vaccine and we are even talking about how racism might be interfering with the messaging we are getting and how the vaccine is distributed to us. We need to address racism, we need to address that as a community and be unafraid. We need to name racism, we have to figure out the levers on which we can intervene, and then we need to engage in collective action. Organize and strategize to act. Collective action, all of us together, will not only protect us, it will propel us.

Dr. Cato Laurencin—Let me just also add, I think it is so important to realize that this is not our last rodeo. Something will be back again, and we have to address racism head-on. If we do not do it now, we will never do it. I believe this is key in terms of making the structural changes that we need to make sure the Black community is not hit as hard as it is in terms of COVID.

Dr. Hannah Valantine—With that, I want to thank you all for the wonderful participation in this webinar. Our work is cut out, but we are strong, and we will succeed. Thank you.

Dr. Cato Laurencin—Thank you, Dr. Valantine. Thank you to the rest of the panel.

Final Authors’ Note

The content of this article is based on current scientific knowledge and clinical and public health best practices. This information and related recommendations will further evolve as we learn more from ongoing research, experiences, and outcomes. Given the dynamic nature of COVID-19, persistent vaccine hesitancy, and evolving mutations, expect the circumstances to change. This discourse should not qualify as medical advice.

References

Laurencin CT, Walker JM. A pandemic on a pandemic: racism and COVID-19 in Blacks. Cell Syst. 2020;11(1):9–10.

Ndugga N, Pham O, Hills L, Artiga S, Mengistu S. Early state vaccination data raise warning flags for racial equity. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). 2021. https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/early-state-vaccination-data-raise-warning-flags-racial-equity/

Shapiro A. Early data shows striking racial disparities in who’s getting the COVID-19 vaccine. NPR. 2021. https://www.wemu.org/post/early-data-shows-striking-racial-disparities-whos-getting-covid-19-vaccine#stream/0

Romero L, Salzman S, Kaitlyn F. Kizzmekia Corbett, an African American woman, is praised as key scientist behind COVID-19 vaccine. ABC News. 2020. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/kizzmekia-corbett-african-american-woman-praised-key-scientist/story?id=74679965

Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–15.

Madjunkov M, Dviri M, Librach C. A comprehensive review of the impact of COVID-19 on human reproductive biology, assisted reproduction care and pregnancy: a Canadian perspective. J Ovarian Res. 2020;13(1):140.

Center of Diseas Control and Prevention (CDC). Coronovirus disease 2019. n.d.. https://www.cdc.gov/

Hamel L, Kirzinger A, Muñana C, Mollyann, B. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: December 2020. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). 2020. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-december-2020/

Laurencin CT, Murdock CJ, Laurencin L, Christensen DM. HIV/AIDS and the African-American Community 2018: a decade call to action. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(3):449–58.

Laurencin CT, Christensen DM, Taylor ED. HIV/AIDS and the African-American community: a state of emergency. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(1):35–43.

Laurencin CT, Walker JM. Racial profiling is a public health and health disparities issue. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;(3):393-397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00738-2.

Nwoko AJ. Moderna vaccine vs. Pfizer vaccine: experts say both are safe and effective. MSN. 2020. https://www.msn.com/en-us/health/medical/moderna-vaccine-vs-pfizer-vaccine-experts-say-both-are-safe-and-effective/ar-BB1c4DlO

Coronavirus. Johnson & Johnson’s one-shot COVID-19 vaccine effective, safe: FDA staff. HuffPost News. 2021. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/johnson-johnsons-one-shot-covid-19-vaccine-effective-safe-fda-staff_n_60365588c5b656e70b92fc5c

Gayle H, Foege W, Brown L, Kahn B. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Equitable Allocation of Vaccine for the Novel Coronavirus. Framework for Equitable Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine. Kahn B, Brown L, Foege W, Gayle H, editors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US).

Daley GQ, Barabino GA, Ajijola OA, Bright CM, Rice VM, Laurencin CT. COVID highlights another crisis: lack of black physicians and scientists. Med (N Y). 2021;2(1):2–3.

Laurencin CT, Murray M. An American crisis: the lack of Black men in medicine. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(3):317–21.

Dehon E, Weiss N, Jones J, Faulconer W, Hinton E, Sterling S. A systematic review of the impact of physician implicit racial bias on clinical decision making. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(8):895–904.

Brooks OT. Diversity in medicine: the low levels of Black physicians to provide Black on Black care is a crime. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(5):469–70.

Owens DC, Fett SM. Black maternal and infant health: historical legacies of slavery. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1342–5.

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(35):21194–200.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of Joanne M. Walker, MS, and Melanie Burnat in preparing the remarks for publication.

Funding

This work received financial support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH BUILD (RL5GM118969).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laurencin, C.T., Valantine, H., Yancy, C. et al. The COVID-19 Vaccine and the Black Community: Addressing the Justified Questions. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8, 809–820 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01082-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01082-9