Abstract

The natural pathway of antioxidant production is mediated through Kelch-like erythroid cell-derived protein with Cap and collar homology [ECH]-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) system. Keap1 maintains a low level of Nrf2 by holding it in its protein complex. Also, Keap1 facilitates the degradation of Nrf2 by ubiquitination. In other words, Keap1 is a down-regulator of Nrf2. To boost the production of biological antioxidants, Keap1 has to be inhibited and Nrf2 has to be released. Liberated Nrf2 is in an unbound state, so it travels to the nucleus to stimulate the antioxidant response element (ARE) present on the antioxidant genes. AREs activate biosynthesis of biological antioxidants through genes responsible for the production of antioxidants. In some cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), there is an enormous release of cytokines. The antioxidant defense mechanism in the body helps in counteracting symptoms induced by the cytokine storm in COVID-19. So, boosting the production of antioxidants is highly desirable in such a condition. In this review article, we have compiled the role of Keap1-Nrf2 system in antioxidant production. We further propose its potential therapeutic use in managing cytokine storm in COVID-19.

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The oxidative stress inducers or pro-oxidants are reactive chemical entities like electrophiles (positively charged species) (Trostchansky et al. 2020), nucleophiles (negatively charged species) (Afanas’ev 2014), free radicals (Chan et al. 2020), metals (Yazdanian et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2019; Haque et al. 2020), and non-specified oxidants (produced by the breakdown of xenobiotics) (Deng et al. 2008). The increase in pro-oxidants induces oxidative stress inside the cells and may be deleterious (Singh and Devasahayam 2020; Ersan et al. 2020). Oxidative stress is negated by antioxidants by neutralizing the pro-oxidants. These antioxidants either intrinsic (produced in the cells) or extrinsic antioxidants (obtained from a natural source or synthetic small molecules) protect the cells from oxidative stress.

The intrinsic mechanism of combating oxidative stress is carried out through the production of antioxidant molecules. Whenever the oxidative stress increases in the cell, the antioxidant genes are expressed entailing the production of intrinsic biological antioxidants (Pulaski et al. 2019). These biological antioxidant molecules act as a shield to the detrimental effects of oxidants on the cellular environment. Some of the biological antioxidants are superoxide dismutase, aldehyde dehydrogenase, and glutathione peroxidase. These bio-molecules help in neutralizing the stressor molecules/pro-oxidants produced during normal metabolism (Lu et al. 2016). This intrinsic balance between pro-oxidants and antioxidants gets deranged in several acute pathological conditions, particularly those that induce cytokine storm.

Cytokine storm is a pathological condition that arise due to abnormally high production of inflammatory mediators (Hirawat et al. 2020). It was found that oxidative stress increases inflammation (Kudo et al. 2012; Wu et al. 2021) and antioxidants help in reducing cytokine production (Ojeaburu and Oriakhi 2021; Toumpanakis et al. 2009). In this direction, it will be intriguing to delve into the possibilities of using Keap1 inhibitors to stimulate the production of antioxidants for controlling COVID-19-induced cytokine storm.

Extrinsic and intrinsic antioxidants

Extrinsic antioxidants may be natural compounds (vitamin C, vitamin A, alpha-tocopherol etc.) or synthetic molecules (phenolic compounds) (Martins et al. 2016). The synthetic molecules exhibit antioxidant activity either through direct action like phenolic antioxidants or through indirect action like antioxidant gene activators.

There exists an intrinsic mechanism that produces antioxidants to neutralize oxidative stress (Franco et al. 1999). With the increase in oxidative stress, the antioxidant genes are expressed initiating the production of intrinsic antioxidants. The antioxidant molecules neutralize the pro-oxidants produced as a result of normal metabolism.

Intrinsic antioxidants prevent oxidative damages to cellular organelles. They play a major role in cell survival, cellular rejuvenation, and prevention of various diseases (Pisoschi et al. 2021). The production of intrinsic antioxidants is triggered by an increase in the levels of charged species and free radicals. These charged species and free radicals are produced during cellular metabolism (e.g. lipid peroxidation) and breakdown of xenobiotics, due to which Kelch-like [ECH] erythroid cell-derived protein with Cap and collar homology-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) system gets activated. Nrf2 ventures into the nucleus and binds to antioxidant response element (ARE) present on antioxidant genes. Antioxidant genes get activated by xenobiotic response element (XRE) and ARE.

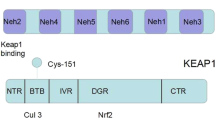

Keap1-Nrf2 system

Keap1-Nrf2 pathway is an important part of cellular defense (Baird and Yamamoto 2020). The production of antioxidants is regulated by Keap1-Nrf2 system (Itoh et al. 1999). Keap1 is a 627 amino acid-containing protein that has five domains. The structure exists as a dimer with N-terminals linked to Keap1 possesses four functional domains: BTB (Broad complex, Tramtrack, and Bric-a-Brac), IVR (intervening region), DGR (double-glycine repeat or Kelch repeat), and CTR (C-terminal region and the C-terminals of Keap1 hold Nrf2 from its Neh2 (Nrf2-ECH homology 2) domain (Lo et al. 2017). Neh2 domain has two linking points, namely DLG and ETGE (Katoh et al. 2005). DLG domain has been named so because it contains DLG (Aspartate–Leucine–Glycine) amino acids. ETGE terminal corresponds to the region where ETGE (Glutamate–Threonine–Glycine–Glutamate) amino acids are present. The 3D structure of Keap1 reveals that it has hydrophobic cavities in three identical chains of amino acids which are twisted. Since each chain is in a dimeric form, the structure of Keap1 appears to be a hexamer. The cysteine-containing regions are electrophile-sensitive spots and act as sensors for oxidative stress. These active sites readily interact with the charged species and cause a conformational change in Keap1. The changed conformer of Keap1 releases Nrf2 from its C-terminal (Tong et al. 2006). The liberated Nrf2 traverses to the nucleus. There it binds to the specific site on DNA to activate antioxidant response element (ARE). It leads to stimulation of ARE-dependent gene expression of a series of antioxidative and cytoprotective proteins including heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and several members of the glutathione S transferases (GST) family (Baird and Dinkova-Kostova 2011; Eggler et al. 2008; Kobayashi and Yamamoto 2005). Figure 1 displays the structure of Keap1-Nrf2 Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI).

Keap1 holds Nrf2 from Neh2 domain. The Neh2 domains bind with C-terminals of Keap1 by several interactions. DLG has a lower affinity towards Kelch domain than ETGE. These protein–protein interaction points break apart when there is a conformational change in Keap1 either by pro-oxidants or by Keap1 inhibitors. Under non-oxidative conditions, Keap1 acts as a down-regulator for Nrf2 by facilitating its degradation. When Nrf2 binds with Ubiquitin (a 20-amino-acid protein), it undergoes ubiquitination and degradation (Sekhar et al. 2002). Figure 2 depicts Keap1-Nrf2 system.

Production of intrinsic antioxidants through Keap1-Nrf2 system: a natural response towards oxidative stress

In a normal and non-oxidative stress condition, the cellular concentration of Nrf2 remains low. It is negatively modulated by the cytoplasmic repressor Keap1 which facilitates proteosomal degradation (Itoh et al. 2004; Dikic 2017). When oxidative stress increases in the cell, Nrf2 escapes ubiquitination (Keap1-mediated degradation). Alternatively, phosphorylation of Nrf2 triggers its release from the protein–protein interaction with Keap1. One such example is phosphorylation mediated by RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR)—like Endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) which dissociates Nrf2/Keap1 interaction (Cullinan et al. 2003).

The amino acid sequence present in the C-terminal of Neh3 domain is a determining factor for activation of ARE. Incomplete sequence or modified sequence at a particular region in Nrf2 fails to activate ARE-dependent antioxidant gene expression. Deletion of the last 16 amino acids of this region abolishes the gene activation without affecting the binding affinity of Nrf2 towards ARE (Nioi et al. 2005). Neh4 and Neh5 domains of Nrf2 independently interact with complimentary parts in ARE. Both of these domains synergistically contribute towards interaction with a protein that binds to CREB (cAMP-Responsive Element-Binding protein) (Katoh et al. 2001). The innate antioxidant bio-molecules synthesis is initiated when antioxidant genes receive a stimulus from ARE and XRE (Ma et al. 2018; Raghunath et al. 2018). Sometimes the quantity of biological antioxidants is not enough to counterpoise oxidative stress. In such cases, antioxidant production activators improve the cellular defense against oxidative stress. Many studies show that stimulation in Nrf2 system by external molecules increases the production of antioxidants (Tran et al. 2019). Hence, Keap1-Nrf2 system is a promising target for small molecules.

Mutations in Keap1 cause variation in the production of antioxidants. Different mutants of Keap1 have been noticed in various cancers (lung cancer, breast cancer, liver and gall bladder cancer). It has been seen that somatic mutation of Keap1 in liver cells allows enhanced expression of Nrf2 which is responsible for detoxification (Poorti et al. 2017).

Production of antioxidants by Keap1 inhibition and Nrf2 activation: extrinsic inhibitors of protein–protein interaction

Several Keap1 inhibitors and Nrf2 activator molecules have been reported in pre-clinical studies. Phytochemicals have also been screened for their activating effect on Nrf2 system (Wu et al. 2014). Some of them are sulforaphane (Kubo et al. 2017), resveratrol (He et al. 2012), curcumin (Ashrafizadeh et al. 2020), spermidine (Liu et al. 2019). Many synthetic molecules have been reported to activate Keap1-Nrf2 system in in-vitro studies (Mou et al. 2020). A study on pentoxifylline shows similar results (Ali et al. 2018).

Relevance of Keap1-Nrf2 system in diseases

Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway is one of the most important regulators of cytoprotective responses to oxidative stresses. It is believed to play a critical role in the development of many diseases (Chunlin et al. 2014), such as cancer (Yu and Kensler 2005), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other airway disorders (Marzec et al. 2007), Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s diseases (DeVries et al. 2008), atherosclerosis, heart diseases (Koenitzer and Freeman 2010), chronic kidney diseases (CKD) (Gao and Mann 2009), diabetes (Uruno et al. 2013), inflammatory bowel diseases (Theiss et al. 2009), rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis (Xu et al. 2021).

Cytokine storm

A systemic inflammatory response either induced by infections or by drugs, is associated with an abnormal increase in activities of immune cells (Gupta et al. 2020). Hence, the term cytokine storm for the pathological condition that ensues (Fajgenbaum and June 2020). The role of oxidative stress in the production of cytokines is well known. Oxidative stressors like reactive oxygen species (ROS) can stimulate the synthesis of NLRP3 and NF-κB which leads to cytokine storm (Bhaskar et al. 2020). The undesirably high levels of cytokines implicate harmful effects on several parts of the body. These include the effects on different organ systems along with constitutional symptoms of fever and systemic inflammation. A diagrammatic representation of the effects of cytokine storm is depicted in Fig. 3.

Role of Keap1 inhibitors in cytokine storm

Cytokine storm as reported in severe conditions of COVID-19 (Lee et al. 2020; Coperchini et al. 2020), worsens the clinical condition of patients and increases the duration of hospitalization. If cytokine storm is treated at its initial stage, the clinical recovery is faster and better. Various approaches for managing COVID-19 conditions have been tried all over the world. In the exploration of effective methods for the treatment of COVID-19, several combinations of drugs and neutraceutical products have been tried. Present scientific literature encourages adjunct to therapy of antioxidants along with the standard treatment, which may include antiviral agents.

Nrf2 has been linked to the repression of stimulators of interferon genes (STING) in human cells. This was confirmed when primary human monocyte-derived macrophages were Nrf2 silenced and the level of STING was observed to be high. This suppression is effective enough to decrease type 1 interferon production (Olagnier et al. 2018). The inflammatory response in osteoarthritis increases when Nrf2 pathway is downregulated (Chen et al. 2019). Keap1 inhibitors and Nrf2 activators have been reported to decrease inflammatory response in acute lung injury (Duran et al. 2016) and cystic fibrosis (Chen et al. 2008). Keap1-Nrf2 pathway has been linked to several genes expression. The up-regulation of Nrf2 has been reported to control inflammation in several studies (Ahmed et al. 2017; Staurengo-Ferrari et al. 2019).

Data from clinical studies

Vitamin C (Ascorbic acid), one of the well-substantiated antioxidant has been studied in COVID-19 and is found to be helpful as an adjunct treatment (Simonson 2020; Feyaerts and Luyten 2020). Furthermore, parenteral vitamin C is helpful in the recovery of COVID-19 patients as it counters cytokine storm (DeMelo and Homem-de-Mello 2020).

Quercetin, a well-known antioxidant was studied in 152 outpatients suffering from COVID-19. The randomized controlled and open-labeled study was carried out for 30 days to show that quercetin is helpful as an adjuvant to the standard treatment in COVID-19 patients. It was reported that during the initial stage of COVID-19 infection, quertcetin phytosome® reduced the duration of hospitalization, the need for oxygen supplementation and deaths (Darband et al. 2020). Quercetin activates Keap1-Nrf2 system and has been reported to mediate anti-inflammatory response (Zhu et al. 2019).

Pentoxifylline along with diosmin is shown to have anti-inflammatory activity through Keap1-Nrf2 system and this is substantiated by a preclinical study (Ali et al. 2018). A clinical study was conducted on 110 patients with moderate to severe pneumonia due to COVID-19. Four groups of 22 patients received pentoxifylline along with vitamin C, vitamin E, N-acetylcysteine, or melatonin and the fifth group received only pentoxifylline. The antioxidant therapy decreased oxidative stress by lowering lipid peroxidation, interleukin 6, C-reactive protein and pro-calcitonin levels. Antioxidant therapy showed clinical improvements in several survival scores (Chavarria et al. 2021).

Pirfenidone is being studied clinically [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04282902] and has ameliorative effects in treating respiratory conditions (Liu et al. 2017). There are very few clinical studies for exploring the effectiveness of antioxidants for controlling COVID-19-induced cytokine storm and lesser are the clinical data available related to Keap1-Nrf2 system.

Conclusion

Keap1 inhibitors or Nrf2 activators may serve as adjunct therapy in strengthening the inherent defense mechanism against infectious conditions like COVID-19. Keap1 inhibitors/Nrf2 activators may alleviate cytokine storm in COVID-19 eventually reducing the complications and facilitating faster and better clinical recovery. Specific inhibitors of Keap1 should be developed for better pharmacological efficacy. Further research on Keap1-Nrf2 system in the context of COVID-19 may potentially lead towards discovery and development of novel Keap1 inhibitors.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable (data transparency).

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Afanas’ev I (2014) New nucleophilic mechanisms of ros-dependent epigenetic modifications: comparison of aging and cancer. Aging Dis 5:52. https://doi.org/10.14336/ad.2014.050052

Ahmed SM, Luo L, Namani A, Wang XJ, Tang X (2017) Nrf2 signaling pathway: pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1863:585–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.005

Ali FE, Bakr AG, Abo-Youssef AM, Azouz AA, Hemeida RA (2018) Targeting Keap-1/Nrf-2 pathway and cytoglobin as a potential protective mechanism of diosmin and pentoxifylline against cholestatic liver cirrhosis. Life Sci 207:50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2018.05.048

Ashrafizadeh M, Ahmadi Z, Mohammadinejad R, Farkhondeh T, Samarghandian S (2020) Curcumin activates the Nrf2 pathway and induces cellular protection against oxidative injury. Curr Mol Med 20(2):116–133. https://doi.org/10.2174/1566524019666191016150757

Baird L, Dinkova-Kostova AT (2011) The cytoprotective role of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Arch Toxicol 85:241–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-011-0674-5

Baird L, Yamamoto M (2020) The molecular mechanisms regulating the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway. Mol Cell Biol 40:e00099-e120. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.00099-20

Bhaskar S, Sinha A, Banach M, Mittoo S, Weissert R, Kass JS, Rajagopal S, Pai AR, Kutty S (2020) Cytokine storm in COVID-19 immunopathological mechanisms, clinical considerations, and therapeutic approaches: the REPROGRAM consortium position paper. Front Immunol 11:1648. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01648

Chan KY, Sik KH, Lee BM (2020) Detoxifying effects of optimal hyperoxia (40% oxygenation) exposure on benzo[a]pyrene-induced toxicity in human keratinocytes. J Toxicol Environ Health Part A 83:82–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2020.1730083

Chavarria AP, Vázquez RR, Cherit JG, Bello HH, Suastegui HC, Moreno-Castañeda L, Estrada GA, Hernández F, González-Marcos O, Saucedo-Orozco H, Manzano-Pech L (2021) Antioxidants and pentoxifylline as coadjuvant measures to standard therapy to improve prognosis of patients with pneumonia by COVID-19. Comput Struct Biotechnol 19:1379–1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.02.009

Chen J, Kinter M, Shank S, Cotton C, Kelley TJ, Ziady AG (2008) Dysfunction of Nrf-2 in CF epithelia leads to excess intracellular H2O2 and inflammatory cytokine production. PLoS ONE 3(10):e3367. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003367

Chen Z, Zhong H, Wei J, Lin S, Zong Z, Gong F, Huang X, Sun J, Li P, Lin H, Wei B (2019) Inhibition of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling leads to increased activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 21:1–13. https://arthritis-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13075-019-2085-6

Chunlin Z, Zhenyuan M, Chunquan S, Wannian Z (2014) Updated research and applications of small molecule inhibitors of Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction: a review. Curr Med Chem 21:1861–1870. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867321666140217104648

Coperchini F, Chiovato L, Ricci G, Croce L, Magri F, Rotondi M (2020) The cytokine storm in COVID-19: further advances in our understanding the role of specific chemokines involved. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 53:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.12.005

Cullinan SB, Zhang D, Hannink M, Arvisais E, Kaufman RJ, Diehl JA (2003) Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol Cell Biol 23(20):7198–7209. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.23.20.7198-7209.2003

Darband SG, Sadighparvar S, Yousefi B, Kaviani M, Ghaderi-Pakdel F, Mihanfar A, Rahimi Y, Mobaraki K, Majidinia M (2020) Quercetin attenuated oxidative DNA damage through NRF2 signaling pathway in rats with DMH induced colon carcinogenesis. Life Sci 253:117584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117584

DeMelo AF, Homem-de-Mello M (2020) High-dose intravenous vitamin C may help in cytokine storm in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Crit Care 24:500. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03228-3

Deng T, Xu K, Zhang L, Zheng X (2008) Dynamic determination of Ox-LDL-induced oxidative/nitrosative stress in single macrophage by using fluorescent probes. Cell Biol Int 32:1425–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.08

DeVries HE, Witte M, Hondius D, Rozemuller AJ, Drukarch B, Hoozemans J (2008) Nrf2-induced antioxidant protection: a promising target to counteract ROS-mediated damage in neurodegenerative disease. Free Radic 45:1375–1383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.001

Dikic I (2017) Proteasomal and autophagic degradation systems. Annu Rev Biochem 86:193–224. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044908

Duran CG, Burbank AJ, Mills KH, Duckworth HR, Aleman MM, Kesic MJ, Peden DB, Pan Y, Zhou H, Hernandez ML (2016) A proof-of-concept clinical study examining the NRF2 activator sulforaphane against neutrophilic airway inflammation. Resp Res 17(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-016-0406-8

Eggler AL, Gay KA, Mesecar AD (2008) Molecular mechanisms of natural products in chemoprevention: induction of cytoprotective enzymes by Nrf2. Mol Nutr Food Res 52:84–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.200700249

Ersan S, Cigdem B, Bakir D, Dogan HO (2020) Determination of levels of oxidative stress and nitrosative stress in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 164:106352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106352

Fajgenbaum DC, June CH (2020) Cytokine storm. N Engl J Med 383:2255–2273. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra2026131

Feyaerts AF, Luyten W (2020) Vitamin C as prophylaxis and adjunctive medical treatment for COVID-19? Nutrition 79:110948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2020.110948

Franco AA, Odom RS, Rando TA (1999) Regulation of antioxidant enzyme gene expression in response to oxidative stress and during differentiation of mouse skeletal muscle. Free Radi Biol Med 27:1122–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00166-5

Gao L, Mann GE (2009) Vascular NAD(P)H oxidase activation in diabetes: a double-edged sword in redox signalling. Cardiovasc Res 82:9–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvp031

Gupta KK, Khan MA, Singh SK (2020) Constitutive inflammatory cytokine storm: a major threat to human health. J Interferon Cytokine Res 40:19–23. https://doi.org/10.1089/jir.2019.0085

Haque MN, Nam SE, Eom HJ, Kim SK, Rhee JS (2020) Exposure to sublethal concentrations of zinc pyrithione inhibits growth and survival of marine polychaete through induction of oxidative stress and DNA damage. Mar Pollut Bull 156:111276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020

He X, Wang L, Szklarz G, Bi Y, Ma Q (2012) Resveratrol inhibits paraquat-induced oxidative stress and fibrogenic response by activating the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 342(1):81–90. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.112.194142

Hirawat R, Saifi MA, Godugu C (2020) Targeting inflammatory cytokine storm to fight against COVID-19 associated severe complications. Life Sci 267:118923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118923

Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Engel JD (1999) Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino terminal Neh2 domain. Genes Dev 13:76–86. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.13.1.76

Itoh K, Tong KI, Yamamoto M (2004) Molecular mechanism activating Nrf2-Keap1 pathway in regulation of adaptive response to electrophiles. Free Radic Biol Med 36:1208–1213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.02.075

Katoh Y, Itoh K, Yoshida E, Miyagishi M, Fukamizu A, Yamamoto M (2001) Two domains of Nrf2 cooperatively bind CBP, a CREB binding protein, and synergistically activate transcription. Genes Cells 6(10):857–868. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00469.x

Katoh Y, Iida K, Kang MI, Kobayashi A, Mizukami M, Tong KI, McMahon M, Hayes JD, Itoh K, Yamamoto M (2005) Evolutionary conserved N-terminal domain of Nrf2 is essential for the Keap1-mediated degradation of the protein by proteasome. Arch Biochem Biophys 433:342–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2004.10.012

Kobayashi M, Yamamoto M (2005) Molecular mechanisms activating the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway of antioxidant gene regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal 7:385–394. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2005.7.385

Koenitzer JR, Freeman BA (2010) Redox signaling in inflammation: interactions of endogenous electrophiles and mitochondria in cardiovascular disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 1203:45–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05559.x

Kubo E, Chhunchha B, Singh P, Sasaki H, Singh DP (2017) Sulforaphane reactivates cellular antioxidant defense by inducing Nrf2/ARE/Prdx6 activity during aging and oxidative stress. Sci Rep 7(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14520-8

Kudo M, Ogawa E, Kinose D, Haruna A, Takahashi T, Tanabe N, Marumo S, Hoshino Y, Hirai T, Sakai H, Muro S (2012) Oxidative stress induced interleukin-32 mRNA expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Res 13:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-13-19

Lee PY, Day-Lewis M, Henderson LA, Friedman KG, Lo J, Roberts JE, Lo MS, Platt CD, Chou J, Hoyt KJ, Baker AL (2020) Distinct clinical and immunological features of SARS-CoV-2-induced multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. J Clin Investig 130:5942–5950. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci141113

Liu Y, Lu F, Kang L, Wang Z, Wang Y (2017) Pirfenidone attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice by regulating Nrf2/Bach1 equilibrium. BMC Pulm Med 17(1):1–1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-017-0405-7

Liu P, de la Vega MR, Dodson M, Yue F, Shi B, Fang D, Chapman E, Liu L, Zhang DD (2019) Spermidine confers liver protection by enhancing NRF2 signaling through a MAP1S-mediated noncanonical mechanism. Hepatology 70(1):372–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30616

Lo JY, Spatola BN, Curran SP (2017) WDR23 regulates NRF2 independently of KEAP1. PLoS Genet 13:e1006762. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006762

Lu MC, Ji JA, Jiang ZY, You QD (2016) The Keap1–Nrf2–ARE pathway as a potential preventive and therapeutic target: an update. Med Res Rev 36:924–963. https://doi.org/10.1002/med.21396

Ma YF, Wu ZH, Gao M, Loor JJ (2018) Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 antioxidant response element pathways protect bovine mammary epithelial cells against H2O2-induced oxidative damage in vitro. J Dairy Sci 101:5329–5344. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2017-14128

Martins N, Barros L, Ferreira IC (2016) In vivo antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds: facts and gaps. Trends Food Sci Technol 48:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2015.11.008

Marzec JM, Christie JD, Reddy SP, Jedlicka AE, Vuong H, Lanken PN (2007) Functional polymorphisms in the transcription factor NRF2 in humans increase the risk of acute lung injury. FASEB J 21:2237–2246. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.06-7759com

Mou Y, Wen S, Li YX, Gao XX, Zhang X, Jiang ZY (2020) Recent progress in Keap1-Nrf2 protein-protein interaction inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem 202:112532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112532

Nioi P, Nguyen T, Sherratt PJ, Pickett CB (2005) The carboxy-terminal Neh3 domain of Nrf2 is required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Bio 25(24):10895–10906. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.25.24.10895-10906.2005

Ojeaburu SI, Oriakhi K (2021) Hepatoprotective antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potentials of gallic acid in carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic damage in Wistar rats. Toxicol Rep 8:177–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2021.01.001

Olagnier D, Brandtoft AM, Gunderstofte C, Villadsen NL, Krapp C, Thielke AL, Laustsen A, Peri S, Hansen AL, Bonefeld L, Thyrsted J (2018) Nrf2 negatively regulates STING indicating a link between antiviral sensing and metabolic reprogramming. Nat Commun 9:3506. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05861-7

Pisoschi AM, Pop A, Iordache F, Stanca L, Predoi G, Serban AI (2021) Oxidative stress mitigation by antioxidants-an overview on their chemistry and influences on health status. Eur J Med Chem 209:112891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112891

Poorti P, Alok KS, Mritunjai S, Mallika T, Hari SS, Indrajeet SG (2017) The see-saw of Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 116:89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.02.006

Pulaski L, Jatczak-Pawlik I, Sobalska-Kwapis M, Strapagiel D, Bartosz G, Sadowska-Bartosz I (2019) 3-Bromopyruvate induces expression of antioxidant genes. Free Radic Res 53:170–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/10715762.2018.1541176

Raghunath A, Sundarraj K, Nagarajan R, Arfuso F, Bian J, Kumar AP, Sethi G, Perumal E (2018) Antioxidant response elements: discovery, classes, regulation and potential applications. Redox Biol 17:297–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2018.05.002

Sekhar KR, Yan XX, Freeman ML (2002) Nrf2 degradation by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway is inhibited by KIAA0132 the human homolog to I Nrf2. Oncogene 21:6829–6834. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1205905

Simonson W (2020) Vitamin C and coronavirus. Geriatr Nurs 41:331–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.05.002

Singh E, Devasahayam G (2020) Neurodegeneration by oxidative stress: a review on prospective use of small molecules for neuroprotection. Mol Biol Rep 47:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-020-05354-1

Staurengo-Ferrari L, Badaro-Garcia S, Hohmann MS, Manchope MF, Zaninelli TH, Casagrande R, Verri WA Jr (2019) Contribution of Nrf2 modulation to the mechanism of action of analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs in pre-clinical and clinical stages. Front Pharmacol 9:1536. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01536

Theiss AL, Vijay-Kumar M, Obertone TS, Jones DP, Hansen JM, Gewirtz AT (2009) Prohibitin is a novel regulator of antioxidant response that attenuates colonic inflammation in mice. J Gastroenterol 137:199–208. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.033

Tong KI, Katoh Y, Kusunoki H, Itoh K, Tanaka T, Yamamoto M (2006) Keap1 recruits Neh2 through binding to ETGE and DLG motifs: characterization of the two-site molecular recognition model. Mol Cell Biol 26:2887–2900. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.26.8.2887-2900.2006

Toumpanakis D, Karatza MH, Katsaounou P, Roussos C, Zakynthinos S, Papapetropoulos A, Vassilakopoulos T (2009) Antioxidant supplementation alters cytokine production from monocytes. J Interferon Cytokine Res 29:741–748. https://doi.org/10.1089/jir.2008.0114

Tran KT, Pallesen JS, Solbak SM, Narayanan D, Baig A, Zang J, Aguayo-Orozco A, Carmona RM, Garcia AD, Bach A (2019) A comparative assessment study of known small-molecule Keap1−Nrf2 protein–protein interaction inhibitors: chemical synthesis, binding properties, and cellular activity. J Med Chem 62(17):8028–8052. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00723

Trostchansky A, Wood I, Rubbo H (2020) Regulation of arachidonic acid oxidation and metabolism by lipid electrophiles. Prostag Oth Lipid M 152:106482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2020

Uruno A, Furusawa Y, Yagishita Y, Fukutomi T, Muramatsu H, Negishi T, Sugawara A, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M (2013) The Keap1-Nrf2 system prevents onset of diabetes mellitus. Mol Cell Biol 33(15):2996–3010. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.00225-13

Wu KC, McDonald PR, Liu J, Klaassen CD (2014) Screening of natural compounds as activators of the keap1-nrf2 pathway. Planta Med 80(01):97–104. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1351097

Wu L, Lu P, Guo X, Song K, Lyu Y, Bothwell J, Wu J, Hawkins O, Clarke SL, Lucas EA, Smith BJ (2021) β-carotene oxygenase 2 deficiency-triggered mitochondrial oxidative stress promotes low-grade inflammation and metabolic dysfunction. Free Radic Biol Med 164:271–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.01.003

Xu XX, Zheng G, Tang SK, Liu HX, Hu YZ, Shang P (2021) Theaflavin protects chondrocytes against apoptosis and senescence via regulating Nrf2 and ameliorates murine osteoarthritis. Food Funct 12(4):1590–1602. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0fo02038a

Yazdanian M, Ghanizadeh G, Rastgoo S, Shokouh SM (2020) Evaluation of kidney function and oxidative stress biomarkers in prolonged occupational exposure with mercury in dentists. Gene Rep 19:100627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genrep.2020.100627

Yu X, Kensler T (2005) Nrf2 as a target for cancer chemoprevention. Mutat Res 591:93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.04.017

Zhou F, Jongberg S, Zhao M, Sun W, Skibsted LH (2019) Antioxidant efficiency and mechanisms of green tea, rosemary or mate extracts in porcine Longissimus dorsi subjected to iron-induced oxidative stress. Food Chem 298:125030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125030

Zhu Q, Liu M, He Y, Yang B (2019) Quercetin protect cigarette smoke extracts induced inflammation and apoptosis in RPE cells. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 47(1):2010–2015. https://doi.org/10.1080/21691401.2019.1608217

Funding

This work is not supported by any funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ES and GSPM contributed to conceptualisation and data collection, NA contributed by proofreading, PSD helped in artwork, AG arranged data and reference, AD reference arrangement.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no competing interest.

Ethical approval

No human studies were done by any of the authors of this manuscript.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

We give our consent to publish this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, E., Matada, G.S.P., Abbas, N. et al. Management of COVID-19-induced cytokine storm by Keap1-Nrf2 system: a review. Inflammopharmacol 29, 1347–1355 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-021-00860-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-021-00860-5