Abstract

An increasing body of literature shows the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown measures on the mental health and well-being of adolescents. However, few studies have examined how national-level lockdown measures, specifically school closures, are related to levels of peer violence among adolescents. The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study allows a unique opportunity to examine cross-nationally across representative samples of adolescents, the relationship between days of school closure and levels of school and cyberbullying perpetration and victimization and physical fighting. The current cross-sectional study, which includes data from 244,405 children (50.6% female) from 42 countries and regions, collected following the return to school (August 2021 to June 2023), showed a negative association between days of school closure and all four forms of bullying perpetration and victimization, but no such relationship with physical fighting. The associations held particularly for boys and older adolescents, for whom the prevalence of bullying perpetration was higher. Results strengthen an ecological model whereby distal structural factors, such as national school policy, shape the expression of peer violence among young people. They also support a theoretical perspective in which school bullying and cyberbullying share common drivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on young people’s mental health and well-being (Samji et al., 2022). A recent systematic review (Kauhanen et al., 2023) of 21 studies from 11 countries found deterioration of children and adolescents’ mental health over time, in association with public health efforts to control the spread of the virus, including higher levels of depression, anxiety and psychological distress, negative affect, and loneliness. A more focused systematic review that examined the impact of lockdown on children and adolescents’ mental health (Panchal et al., 2023) found significant associations between COVID-19 lockdown and depression, anxiety, boredom, stress, loneliness, anger, irritability, and psychological distress. However, despite a wealth of evidence on their potential mental health impacts, few studies have focused on the effects of public health measures during the pandemic on peer violence among adolescents. Findings from existing studies remain inconsistent (Vaillancourt et al., 2023) with some demonstrating decreases in bullying, which have been attributed to limited levels of contact (Borualogo & Casas, 2023; Repo et al., 2023), while others have shown increases (Forsberg & Thorvaldsen, 2022; Xie et al., 2023). This remains an important gap in public health evidence due to the importance of adolescent violence as a societal problem, and the need to understand all, including unintended, effects of public health measures implemented during pandemics.

Questions remain about the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic and related policies impacted young people’s expressions of violence, including traditional school bullying and cyberbullying (Vaillancourt et al., 2021). In addition, international cross-national studies examining such impacts are uncommon although needed to shed light on the effects of national-level school policies on adolescent peer violence. Public policies introduced to limit the spread and impact of the COVID-19 virus differed from country to country (Egger et al., 2021), though most brought in measures such as closures of schools, workplaces, public transport, cancellations of public events, restrictions of internal movement, tracing infected person contacts, and enhanced viral testing (Castex et al., 2021). These cross-country differences in school closures allow us to assess the relationship between the duration of school closures and adolescent outcomes. As such, systematic evidence from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) showed that lengths of school closures impacted student learning outcomes (Jakubowski et al., 2024).

From a theoretical perspective, according to a Routine Activity Theory (RAT) (Cohen & Felson, 1979), bullying can take place when three elements converge: a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of capable guardianship (Cecen-Celik & Keith, 2019; Malinski et al., 2023). RAT (Cohen & Felson, 1979) could suggest that school bullying during COVID-19 school closures would have decreased because adolescents reversed to remote schooling, hence reducing face-to-face interactions. The lack of physical proximity removed the “suitable targets” and the environment where bullying often thrives (e.g. unsupervised hallways, lunchrooms, or playgrounds). However, the shift to online learning increased screen time and reliance on digital communication, creating new “suitable targets” in virtual spaces (Li et al., 2021) for motivated offenders. School closures may have led to increased stress, frustration, increased time on screens, and lack of supervision (Viner et al., 2022) which may have increased levels of cyberbullying (Barlett et al., 2021). Guardianship in online spaces (e.g. monitoring by teachers or parents) is often less effective compared to in-person oversight (Aizenkot, 2022). An RAT perspective is supported by a recent meta-analysis of 79 studies in the USA which found that rates of traditional bullying during the pandemic were lower as compared with levels prior to the pandemic while levels of cyberbullying were either unchanged or, for certain groups, such as boys and certain ethnic groups, increased (Kennedy & Dendy, 2024).

Empirical studies in individual countries have shown inconsistent results. A recent Norwegian study (Forsberg & Thorvaldsen, 2022) that documented experiences of violence in adolescents before and during the pandemic demonstrated increased levels of both traditional school bullying and cyberbullying victimization. Similar findings were reported in China, attributed to a manifestation of pandemic-induced psychological distress (Xie et al., 2023). However, data from Finland indicates that the prevalence of general peer victimization and cyberbullying victimization decreased during the school lockdown (Repo et al., 2023). More positively, decreased face-to-face interactions with peers may have limited the opportunities to engage in traditional forms of violence, including both bullying and physical fighting, and hence offer respite to bullied adolescents (Repo et al., 2023), while online expressions of cyberbullying may be unchanged (Bacher-Hicks et al., 2021; Vaillancourt et al., 2021) or increased as they offer adolescents opportunities to channel their aggression through digital violence. A recent report based on data on peer violence in 44 countries, and including data before and after the pandemic found no change in face-to-face violence, and a small increase in cyberbullying perpetration and victimization (Cosma et al., 2024). However, studies to date have not taken into account national policy differences in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and how these may have impacted violent behaviours.

In this paper, we had a unique opportunity to explore the potential impact of school closures on adolescent peer violence in a cross-national cross-sectional study. The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study involves an ongoing, international survey of health behaviours in children from around 50 countries. Since the 2021/22 cycle of HBSC was conducted throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, its data allowed us to explore patterns of peer violence among adolescents aged 11 to 15 years, and whether such patterns were associated with country-level policies surrounding the duration of COVID-19-related school closures, with due consideration of the influence of age, gender, and socio-economic status. Available measures of violence included indicators of school bullying perpetration and victimization, cyberbullying perpetration and victimization, and physical fighting. As such, the aims of the current study were to examine whether there was an association between the duration of COVID-19-related school closures and levels of bullying and fighting among school-aged children following the return to school and whether any association was consistent across age and gender. In line with RAT (Cohen & Felson, 1979), we hypothesized that longer duration of school closures would be related to lower levels of engagement in traditional forms of violence (victimization, perpetration, and physical fighting) and higher levels of cyberbullying (victimization and perpetration).

Methods

Sample

The HBSC study is a large cross-sectional, school-based survey carried out every 4 years in collaboration with the WHO (World Health Organisation) Regional Office for Europe among representative samples of 11-, 13-, and 15-year-olds using a standardized protocol (Inchley et al., 2023). The current analysis was based upon reports from 244,405 children (50.6% female) from 42 countries and regions. Samples were drawn using cluster sampling, with school classes or the whole school as the primary sampling unit. Each country obtained ethical board approval (see Table 1 for characteristics of the sample in each participating country). The HBSC survey includes mandatory items that all countries must use, as well as optional items and country-specific items that countries can choose to use. In the 2021–2022 survey, following the COVID-19 pandemic, a new COVID-19 impact scale (see below) was introduced as an optional package. Twenty-eight countries used this scale (slightly over 122,000 adolescents). Analysis was carried out firstly for all 42 countries, without the COVID-19 impact scale, and then among the 28 countries that did use the scale, controlling for COVID-19 impact, to test the robustness of the findings. The data for the current study were collected between August 2021 and June 2023 during school time. This gave us the ability to evaluate the association between policy initiatives such as the duration of school closures and individual-level behaviours at later stages of the pandemic.

Measures

Bullying

Traditional bullying perpetration and victimization were measured using two items adapted from the Olweus Bullying Questionnaire (Olweus, 1997). “How often have you taken part in bullying another person(s) at school (been bullied at school) in the last couple of months”: “I have not bullied another person at school in the last couple of months”; “It has happened once or twice”; “2 or 3 times a month”; “About once a week”; “Several times a week”. The question was preceded by a five-sentence explanation of what was regarded as bullying. As per precedent (Cosma et al., 2022; Craig et al., 2020), responses were recoded as 0 (never or once) and 1 (two to three times or more).

Cyberbullying

Participants were asked: “In the past couple of months how often have you taken part in cyberbullying (e.g. sent mean instant messages, email or text messages; wall postings; created a website making fun of someone; posted unflattering or inappropriate pictures online without permission or shared them with others)” in order to measure perpetration and “In the past couple of months how often have you been cyberbullied?” (with the same examples) to measure victimization (Cosma et al., 2022). Response categories were the same as for traditional bullying and were recoded as 0 (never or once) and 1 (two to three times or more).

Physical Fighting

Participants were asked, “During the past 12 months how many times were you involved in a physical fight”: “I have not been in a physical fight”; “one time”; “two times”; “three times”; “four or more times.” The frequency of fighting is a validated construct with extensive use in international youth risk behaviour surveys (Waxweiler et al., 1993). As per precedent, response categories were recoded as 0 (never, once, or twice) and 1 (three times or more) (Walsh et al., 2013).

School Closures

Since January 2020, the WHO Public Health and Social Measures (PHSM) database (https://phsm.euro.who.int/description) tracked daily changes in various public health and social measures by local and national governments that were intended to suppress or stop the spread of COVID-19. School closures were coded on a five-point scale: 0 (no measures), 1 (adapting in-person teaching with physical distancing, hand hygiene, masks, staggered classes, and separate arrival), 2 (recommended suspension of in-person teaching and transitioning to online/distance learning), 3 (compulsory suspension of in-person teaching on some levels or categories, e.g. just in secondary schools), or 4 (compulsory suspension of all in-person teaching). For this analysis, we calculated the cumulative days of national compulsory suspension of all in-person teaching (coded “4”) up to the date of HBSC data collection. Therefore, while these are country-level data, some within-country variation was observed in school closures in countries that collected HBSC data over an extended period in 2021 and 2022. Across countries, there was a mean of 102 days of school closure, ranging from 0 days in Finland and Sweden to 229 days in Kyrgyzstan (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). Countries were then assigned to approximately equally sized tercile groups (low, medium, high) based on the distribution of the length of school closures (see Fig. 1).

COVID-19 Impact

A ten-item scale was developed for the 2021/2022 survey cycle to measure the perceived impact of the pandemic on various aspects of youth well-being (e.g. home environment, schooling, social relationships; see appendix) (Residori et al., 2023). Responses to each item were given on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very negative) to 5 (very positive). Based on Rasch modeling results on the data collected in different contexts and languages, we collapsed the first two response categories (very negative and negative) to create a 4-point response scale (α = 0.91) and then reverse-scored the items (so that higher scores indicated more negative impact) and calculated the average response across the ten items, giving the scale a range of 1 to 4.

Covariates

Covariates included gender (male or female), age group (11, 13, or 15 years), family wealth (tercile), and national wealth (GDP per capita, measured in 2021 international dollars at purchasing power parity [PPP]). Family wealth was measured using a 6-item index of material assets and family activities (cars, computers, family vacations, bathrooms, own bedroom, dishwasher), and tercile groups were constructed based on a weighted proportional rank in the total score within country samples (Torsheim et al., 2016).

Analysis

The data were analysed using Stata/SE 18.0 (College Station, TX). Associations of each dichotomous youth violence variable (bullying perpetration and victimization, cyberbullying perpetration and victimization, and fighting) with school closures (low [reference group], medium or high) and COVID-19 impact (continuous score) were examined using weighted and modified multilevel Poisson regressions and reported as a prevalence ratio (PR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). These models used robust clustered standard errors to account for school-level clustering in the dataset and included random effects of country differences with fixed effects of the covariates—gender (male/female), age group (11-, 13-, and 15-year-olds), family wealth tertile (low, medium, high), and national wealth (in thousands of international dollars). In the modified version of the Poisson model, a binary outcome replaced the more typical outcome of counts, and parameter estimates (beta values) were exponentiated to produce unbiased estimates of relative risk, with robust SEs recommended for calculating confidence intervals in the face of clustered data (Knol et al., 2012; Zou, 2004).

Results

Cross-National Differences in Bullying

Table 1 shows the distributions of bullying, cyberbullying, fighting, COVID-19 impact, and days of school closures across countries. The mean level of bullying perpetration across countries was 6.1% over the last couple of months (ranging from 2.0% Netherlands to 14.6% Latvia); for bullying victimization, the mean level across countries was 11.1% (ranging from 4.7% Spain to 19% Latvia); for cyberbullying perpetration, the mean level across countries was 4.6% (ranging from 0.8% Spain to 12.2% Lithuania); for cyberbullying victimization, the mean level across countries was 5.6% (ranging from 1.9% Spain to 13.3% Lithuania); for fighting, the mean level across countries was 10.0% per year (ranging from 5.2% Portugal to 14.3% Hungary).

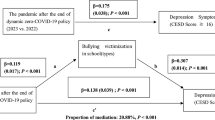

Relationships Between Length of School Closures and Bullying and Fighting

Prevalence ratios for four of the five violence outcomes were significantly higher among boys compared with girls (see Table 2). Levels of bullying and cyberbullying perpetration were also higher among 15-year-olds, compared with younger adolescents, while levels of bullying and cybervictimization and fighting were significantly lower in the 15-year-old age group relative to 11-year-old adolescents. Overall, longer durations of school closures (141 to 230 days) were significantly (p < 0.01) associated with lower levels of two measures (bullying victimization and cybervictimization), but not for the other three measures. When examining different patterns by gender and age, these associations were present for boys (bullying victimization, cyberbullying, and cybervictimization) and 15-year-old adolescents (bullying victimization, cyberbullying, and cybervictimization) (see Tables 3 and 4). In the case of girls and 11-year-old adolescents, while associations were in a similar direction, they were statistically significant only for cybervictimization for girls.

Further analysis examined the relationship between length of school closures and violence among adolescents from the 28 countries that included the COVID-19 impact scale (see supplementary table S1). Prevalence ratios for all five violence measures were significantly higher for those adolescents who reported higher levels of COVID-19 impact. In addition, the negative association between longer durations of school closures and the four bullying measures remained with simultaneous control for this self-report COVID-19 impact measure.

Discussion

In this unique cross-national study, we set out to examine the relationship between national policies surrounding school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic and levels of bullying perpetration and victimization and fighting across representative samples of adolescents across 42 countries in Europe, Central Asia, and Canada. Our most important findings were the identification of relationships between the length of school closures and levels of bullying, both school and cyber, and both perpetration and victimization. Adolescents in countries with a longer duration of school closures reported lower levels of bullying behaviour on their return to school. While school closures and “lockdowns” during COVID-19 were intended to control the spread of the virus, the unintended consequences on mental health have been documented (Castex et al., 2021; Panchal et al., 2023). Our analysis extends these findings by outlining implications for adolescent involvement in peer violence upon their return to schools.

Our study builds upon an evidence base that suggests that peer violence was indeed reduced among school children during or immediately after the COVID-19 lockdowns (Bacher-Hicks et al., 2021; Patte et al., 2024; Repo et al., 2023; Vaillancourt et al., 2023). In contrast to our hypothesis, this was not only for face-to-face school bullying but also for cyberbullying. Further, as these data were collected following a return to in-person school, our findings suggest that this pattern was stronger in countries with longer school closures. This finding is interesting to examine in more detail. It is plausible that being out of school may have broken existing power dynamics which lead to bullying (Olweus, 1993) meanwhile giving a respite to those already bullied at school (Repo et al., 2023). As such, it may take time to re-establish dominance hierarchies relevant to bullying on return to school. Others have shown that being isolated and lonely during the pandemic, as many young people were (Farrell et al., 2023), may have also made young people more appreciative of their peers. Additionally, it is possible that there were higher levels of adult supervision and involvement following the pandemic as adults (teachers, parents, counsellors) may have been concerned with young people’s well-being.

According to RAT (Cohen & Felson, 1979), bullying demands a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of capable guardianship. During lockdown, many adults were more at home and therefore were more able to supervise their children’s online communication (Magis‐Weinberg et al., 2021). This increased parental involvement may have continued when young people returned to school, as parents may have got used to being more aware of their children’s digital activity. Results also reinforce an extension perspective of bullying (Kowalski et al., 2023) in which cyberbullying is seen as an extension or subset of traditional bullying with similar determinants and outcomes. As such, lack of face-to-face interaction may impact not only traditional bullying but also overflow to cyberbullying (which may occur as a continuum of face-to-face interaction). In other contexts, the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns remained for a considerable period of time following the return to school, and behaviours established during lockdown may have persisted (Yuan et al., 2023). However, corroborating these findings with others that show that bullying has rebounded with the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions (Patte et al., 2024), future studies would need to explore whether and how the population-level long-term trends were disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In our analysis, effects were mainly observed among boys and older adolescents who were the groups most highly involved in the perpetration of violence, and, as such, the effects of school closure may have been greatest for these at-risk populations. Findings reinforce previous studies showing higher involvement of boys, in comparison to girls in face-to-face bullying and school fighting (de Looze et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2019), as well as the need to understand the impact of COVID-19 within a gendered lens (Hoyt et al., 2023). We can suggest that since girls and boys tend to express their bullying differently, with girls exhibiting more relational and indirect bullying and boys more direct and physical, (Wang et al., 2009), the lockdowns would have a greater impact on bullying among boys who lacked the physical arena in which to bully.

On a more general level, our results demonstrate a consistent relationship between national-level policy and adolescent bullying behaviour, in this case as exemplified by school closures during the pandemic. This is interesting on several levels. This finding resonates with applications of the ecological model (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), which suggests that bullying and other health risk behaviours develop not just from proximal “drivers” of adolescent well-being and behaviour, but also from more distal macro-level contextual factors (Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Matjasko et al., 2010; Swearer et al., 2012). The current study examined school closures as a macro factor; however, it may be that this policy indicator was associated with additional national factors (Alfano, 2022; Egger et al., 2021). For example, governments with stringent school lockdown measures may also have been more stringent in other responses to the pandemic in general, which may be more important etiologically, such as healthcare-related measures or overall lockdown measures that were not accounted for in the present analysis. They may also represent more interventionist governments, which may be more interventionist in additional ways, such as with anti-bullying programs in schools. While our methodology and HBSC data allow us to address many important questions in this field of enquiry, there is scope for other groups to now add to our understanding of the impact different national COVID-19 preventive measures had on youth violence. Our findings depicted similar relationships between durations of school closures and both face-to-face and cyberbullying. These findings are important theoretically. An extension perspective (Khong et al., 2020; Kowalski et al., 2022) suggests that there is a significant overlap between face-to-face and cyberbullying, with shared drivers and outcomes of the behaviours. Such a perspective sees bullying as a trans-contextual phenomenon (Lazuras et al., 2017) in which young people who bully in “face-to-face” manners are more likely to engage in cyberbullying than those who never engage in bullying. From this perspective, online communication complements (Waytz & Gray, 2018) or enhances (Lieberman & Schroeder, 2020) face-to-face behaviours with young people moving fluidly between the two modes of communication (Reich et al., 2012; Yau & Reich, 2018). However, it is also notable that we identified no statistically significant association between school closures and levels of physical fighting. This suggests that adolescent fighting and bullying may represent distinct social phenomenon with different aetiologies. Since the fighting measure did not stipulate peers or the school context, adolescents may have been reporting fighting with their siblings or other family members, in the tension and stress endured at home under lockdown (Field, 2021; Perkins et al., 2021).

Implications for Practice

The findings are also important for considering policies or programs that could reduce bullying outside of the pandemic. Policies should focus on providing robust mental health support, including counselling and mental health education. The school programs should include virtual components to address online bullying, which may be more prevalent during remote learning (Kennedy & Dendy, 2024). Interventions should include programs that help students develop healthy social interactions and conflict resolution skills. In line with RAT (Aizenkot, 2022; Cecen-Celik & Keith, 2019; Cohen & Felson, 1979), policies could include resources and training for parents to support their children’s social and emotional development. Ensuring a safe and supportive school environment, including training staff to recognize and address signs of peer violence, breaking down bullying hierarchies and providing safe spaces for students to report incidents are imperative. Lockdowns may have led to parents being more present and more aware of what is going on in their children’s online lives. Thus, from an intervention perspective, increasing adult supervision in both face-to-face and cyber contexts, addressing peer dynamics, and disrupting dominance structures within peer groups may be effective intervention strategies. Effective intervention strategies such as the KiVa program (Salmivalli et al., 2011, 2013) address the role of peers and increase the awareness of teachers.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

Strengths of our study include its novelty, the cross-national nature of our study protocol and associated data collection, and our use of standard indicators of violence that are well established and validated over decades of research. Study limitations also warrant comment. The cross-sectional nature of the study limits our ability to make causal inferences due to a lack of knowledge about temporality, although in truth it is unlikely that violence itself was a risk factor for school closures; i.e. reverse causality in this situation is highly unlikely. However, it is still possible that the mechanisms that underlie the observed relationships are not accounted for, and school closures may be a marker for such mechanisms at a contextual level. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of the study did not allow us to control for baseline levels of study variables. As a school-based survey, HBSC data were collected once adolescents returned to school; hence, our analysis demonstrates the potential longer-term impact of lockdowns, rather than their immediate and acute effects on peer violence. Some limitations in the dataset should be noted. First, PHSM data on school closures did not differentiate between nations of the UK (England, Scotland, and Wales). Also, the HBSC study has two subnational surveys in Belgium (French and Flemish), which were linked to the same PHSM data. Also, the COVID-19 impact scale was used by 28 of the 42 countries/regions in our analysis, resulting in different sample sizes. In addition, since we chose to look at gender and age in separate analysis, we did not examine if gender and age differences were significant. Future analysis should focus on how the lockdowns may have impacted differently on boys and girls as they go through adolescence. Finally, the analyses relied on data from Europe, Central Asia, and North American regions; therefore, future studies can expand this work by including countries from the Global South.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this novel international study examined the potential impacts of public health measures involving school closures on risks for various indicators of adolescent violence. It demonstrates the potential influence of such lockdowns on an additional measure of adolescent health, which goes far beyond the control of the virus or the mental health impacts of prolonged isolation from peers and school communities. Such evidence is helpful when considering the value of public health strategies more holistically, beyond their intended effects. The cross-national nature of this new evidence suggests that such effects may cross countries and cultures, and are important to the health of young people generally.

Data Availability

Raw international data from the 2021/22 HBSC survey is under embargo until October 2026. Previous HBSC survey data is available from the open-access data portal https://www.uib.no/en/hbscdata/113290/open-access.

Abbreviations

- HBSC :

-

Health Behaviour in School-aged Children

- COVID-19 :

-

Coronavirus disease

- PISA :

-

Programme for International Student Assessment

- RAT :

-

Routine Activity Theory

- WHO :

-

World Health Organisation

- PHSM :

-

Public Health and Social Measures database

- GDP :

-

Gross domestic product

- PPP :

-

Purchasing power parity

- PR :

-

Prevalence ratio

- CI :

-

Confidence interval

- SE :

-

Standard estimate

References

Aizenkot, D. (2022). The predictability of routine activity theory for cyberbullying victimization among children and youth: Risk and protective factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13–14), NP11857-NP11882.

Alfano, V. (2022). The effects of school closures on COVID-19: A cross-country panel analysis. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 20(2), 223–233.

Bacher-Hicks, A., Goodman, J., Green, J. G., & Holt, M. K. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted both school bullying and cyberbullying. EdWorkingPaper No. 21–436. Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University.

Barlett, C. P., Rinker, A., & Roth, B. (2021). Cyberbullying perpetration in the COVID-19 era: An application of general strain theory. The Journal of Social Psychology, 161(4), 466–476.

Borualogo, I. S., & Casas, F. (2023). Sibling bullying, school bullying, and children’s subjective well-being before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Child Indicators Research, 16, 1203–1232.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons.

Castex, G., Dechter, E., & Lorca, M. (2021). COVID-19: The impact of social distancing policies, cross-country analysis. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change, 5(1), 135–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-020-00076-x

Cecen-Celik, H., & Keith, S. (2019). Analyzing predictors of bullying victimization with routine activity and social bond perspectives. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(18), 3807–3832.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociologial Review, 44 (4), 588–608. In.

Cosma, A., Bjereld, Y., Elgar, F. J., Richardson, C., Bilz, L., Craig, W., Augustine, L., Molcho, M., Malinowska-Cieślik, M., & Walsh, S. D. (2022). Gender differences in bullying reflect societal gender inequality: A multilevel study with adolescents in 46 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 71(5), 601–608.

Cosma, A., Molcho, M., & Pickett, W. (2024). A focus on peer violence in Europe and Central Asia and Canada. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children international report from the 2021/2022 survey. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. .

Craig, W., Boniel-Nissim, M., King, N., Walsh, S. D., Boer, M., Donnelly, P. D., Harel-Fisch, Y., Malinowska-Cieślik, M., de Matos, M. G., & Cosma, A. (2020). Social media use and cyber-bullying: A cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), S100–S108.

Egger, C. M., Magni-Berton, R., Roché, S., & Aarts, K. (2021). I do it my way: Understanding policy variation in pandemic response across Europe. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 622069.

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2003). Bullying in American schools: A socio-ecological prespective on prevention and intrevention. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Farrell, A. H., Vitoroulis, I., Eriksson, M., & Vaillancourt, T. (2023). Loneliness and well-being in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Children, 10(2), 279.

Field, T. (2021). Aggression and violence affecting youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Journal of Psychiatry Research Reviews & Reports, 129, 1–6.

Forsberg, J. T., & Thorvaldsen, S. (2022). The severe impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bullying victimization, mental health indicators and quality of life. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 22634.

Inchley, J., Currie, D., Samdal, O., Jåstad, A., Cosma, A., & Nic Gabhainn, S. (2023). Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study protocol: Background, methodology and mandatory items for the 2021/22 survey.

Jakubowski, M., Gajderowicz, T., & Patrinos, H. (2024). COVID-19, school closures, and student learning outcomes: New global evidence from PISA (GLO Discussion Paper, No. 1372, Global Labor Organization (GLO), Essen, Issue.

Kauhanen, L., Wan MohdYunus, W. M. A., Lempinen, L., Peltonen, K., Gyllenberg, D., Mishina, K., Gilbert, S., Bastola, K., Brown, J. S., & Sourander, A. (2023). A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(6), 995–1013.

Kennedy, R. S., & Dendy, K. (2024). Traditional bullying and cyberbullying victimization before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Bullying Prevention. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00255-4

Khong, J. Z., Tan, Y. R., Elliott, J. M., Fung, D. S. S., Sourander, A., & Ong, S. H. (2020). Traditional victims and cybervictims: Prevalence, overlap, and association with mental health among adolescents in Singapore. School Mental Health, 12, 145–155.

Knol, M. J., Le Cessie, S., Algra, A., Vandenbroucke, J. P., & Groenwold, R. H. (2012). Overestimation of risk ratios by odds ratios in trials and cohort studies: Alternatives to logistic regression. CMAJ, 184(8), 895–899.

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., & Feinn, R. S. (2022). Is cyberbullying an extension of traditional bullying or a unique phenomenon? A longitudinal investigation among college students. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 5, 227–244.

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., & Feinn, R. S. (2023). Is cyberbullying an extension of traditional bullying or a unique phenomenon? A longitudinal investigation among college students. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 5(3), 227–244.

Lazuras, L., Barkoukis, V., & Tsorbatzoudis, H. (2017). Face-to-face bullying and cyberbullying in adolescents: Trans-contextual effects and role overlap. Technology in Society, 48, 97–101.

Li, Q., Luo, Y., Hao, Z., Smith, B., Guo, Y., & Tyrone, C. (2021). Risk factors of cyberbullying perpetration among school-aged children across 41 countries: A perspective of routine activity theory. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 3, 168–180.

Lieberman, A., & Schroeder, J. (2020). Two social lives: How differences between online and offline interaction influence social outcomes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 16–21.

Magis-Weinberg, L., Gys, C. L., Berger, E. L., Domoff, S. E., & Dahl, R. E. (2021). Positive and negative online experiences and loneliness in Peruvian adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 717–733.

Malinski, R., Holt, T. J., Cale, J., Brewer, R., & Goldsmith, A. (2023). Applying routine activities theory to assess on and offline bullying victimization among Australian youth. Journal of School Violence, 22(1), 1–13.

Matjasko, J. L., Needham, B. L., Grunden, L. N., & Farb, A. F. (2010). Violent victimization and perpetration during adolescence: Developmental stage dependent ecological models. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1053–1066.

Olweus, D. (1997). Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 12, 495–510.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell Publishers.

Panchal, U., Salazar de Pablo, G., Franco, M., Moreno, C., Parellada, M., Arango, C., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(7), 1151–1177.

Patte, K. A., Gohari, M. R., Lucibello, K. M., Bélanger, R. E., Farrell, A. H., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2024). A prospective and repeat cross-sectional study of bullying victimization among adolescents from before COVID-19 to the two school years following the pandemic onset. Journal of School Violence, 1–19.

Perkins, N. H., Rai, A., & Grossman, S. F. (2021). Physical and emotional sibling violence in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Family Violence, 37, 745–752.

Reich, S. M., Subrahmanyam, K., & Espinoza, G. (2012). Friending, IMing, and hanging out face-to-face: Overlap in adolescents’ online and offline social networks. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 356–368.

Repo, J., Herkama, S., & Salmivalli, C. (2023). Bullying interrupted: Victimized students in remote schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 5(3), 181–193.

Residori, C., Kolto, A., Varnai, D. E., & Nic Gabhain, S. (2023). Age, gender and class: How the COVID-19 pandemic affected school-aged children in the WHO European Region. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people’s health and well-being from the findings of the HBSC survey round 2021/2022. . Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Salmivalli, C., Kärnä, A., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Counteracting bullying in Finland: The KiVa program and its effects on different forms of being bullied. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(5), 405–411.

Salmivalli, C., Poskiparta, E., Ahtola, A., & Haataja, A. (2013). The implementation and effectiveness of the KiVa antibullying program in Finland. European Psychologist.

Samji, H., Wu, J., Ladak, A., Vossen, C., Stewart, E., Dove, N., Long, D., & Snell, G. (2022). Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth-a systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 27, 173–189.

Swearer, S. M., Espelage, D. L., Koenig, B., Berry, B., Collins, A., & Lembeck, P. (2012). A social-ecological model for bullying prevention and intervention in early adolescence. Handbook of school violence and school safety, 333–355.

Torsheim, T., Cavallo, F., Levin, K. A., Schnohr, C., Mazur, J., Niclasen, B., Currie, C., Group, F. D. S. (2016). Psychometric validation of the revised family affluence scale: A latent variable approach. Child Indicators Research, 9, 771–784.

Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H., Krygsman, A., Farrell, A. H., Landon, S., & Pepler, D. (2021). School bullying before and during COVID-19: Results from a population-based randomized design. Aggressive Behavior, 47(5), 557–569.

Vaillancourt, T., Farrell, A. H., Brittain, H., Krygsman, A., Vitoroulis, I., & Pepler, D. (2023). Bullying before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Opinion in Psychology, 53, 101689.

Walsh, S. D., Molcho, M., Craig, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Huynh, Q., Kukaswadia, A., Aasvee, K., Vֳ¡rnai, D., Ottova, V., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2013). Physical and emotional health problems experienced by youth engaged in physical fighting and weapon carrying. PloS one,8(2), e56403

Waxweiler, R. J., Harel, Y., & O’Carroll, P. W. (1993). Measuring adolescent behaviors related to unintentional injuries. Public Health Reports, 108(1), 11–14.

Waytz, A., & Gray, K. (2018). Does online technology make us more or less sociable? A preliminary review and call for research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(4), 473–491.

Xie, L., Da, Q., Huang, J., Peng, Z., & Li, L. (2023). A cross-sectional survey of different types of school bullying before and during COVID-19 in Shantou City, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2103.

Yau, J. C., & Reich, S. M. (2018). Are the qualities of adolescents’ offline friendships present in digital interactions? Adolescent Research Review, 3(3), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0059-y

Yuan, K., Bao, Y., Leng, Y., & Li, X. (2023). The acute and long-term impact of COVID-19 on mental health of children and adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14.

Zou, G. (2004). A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159(7), 702–706.

Acknowledgements

Health Behaviour in School-aged Children is an international study carried out in collaboration with the World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe. The International Coordinator was Jo Inchley (University of Glasgow, UK). The Data Bank Manager was Professor Oddrun Samdal (University of Bergen). The survey data included in this study were conducted by the following principal investigators in the 42 countries: Albania (Gentiana Qirjako), Armenia (Sergey Sagsyan and Marina Melkumova), Austria (Rosemarie Felder-Puig), Flemish Belgium (Maxim Dirckens), French Belgium (Katia Castetbon), Bulgaria (Anna Alexandrova-Karamanova, Elitsa Dimitrova), Canada (William Pickett, Wendy Craig,), Croatia (Ivana Pavic Simetin), Czech Republic (Michal Kalman), Denmark (Katrine Rich Madsen), England (Sally Kendall, Sabina Hulbert), Estonia (Leila Oja), Finland (Leena Paakkari), France (Emmanuelle Godeau), Germany (Matthias Richter), Greece (Anna Kokkevi, Anastasios Foutiou), Hungary (Ágnes Németh), Iceland (Arsaell M. Arnarsson and Thoroddur Bjarnason), Ireland (Saoirse Nic Gabhainn), Israel (Yossi Harel-Fisch), Italy (Franco Cavallo), Latvia (Iveta Pudule), Lithuania (Kastytis Šmigelskas), Luxembourg (Carolina Catunda), Malta (Charmaine Gauci), the Netherlands (Gonneke Stevens, Saskia van Dorsselaer), North Macedonia (Lina Kostarova Unkovska), Poland (Anna Dzielska), Portugal (Margarida Gaspar de Matos and Tania Gaspar), Republic of Moldova (Galina Lesco), Romania (Adriana Baban), Scotland (Jo Inchley), Serbia (Jelena Gudelj Rakic), Slovakia (Andrea Madarasova Geckova), Slovenia (Helena Jericek), Spain (Carmen Moreno), Sweden (Petra Löfstedt), Switzerland (Marina Delgrande-Jordan), Tajikistan (Sabir Kurbanov &Zohir Nabiev), and Wales (Chris Roberts). The data collection for each HBSC survey is funded at the national level. We thank all the pupils, teachers, and investigators who took part in the HBSC surveys.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Bar-Ilan University. The study was supported by the project, Research of Excellence on Digital Technologies and Wellbeing CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004583, which is co-financed by the European Union.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in the conceptualization of the paper; SDW, WP, and FE were responsible for leading the development of the paper and the first draft; FE led the statistical analysis. All authors were involved in revising the initial draft and writing and in approving the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study received ethical approval from the relevant university and/or research centre Institutional Research Board (IRB) in each participating country and was conducted in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted following informed consent from the participants and parental consent in line with the demands of each IRB.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Walsh, S.D., Elgar, F., Craig, W. et al. COVID-19 School Closures and Peer Violence in Adolescents in 42 Countries: Evidence from the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-025-00296-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-025-00296-3