Abstract

Spatial disparities in quality of life drive population movement between regions. This study explores how concerns related to remote work and health influence intentions to migrate between urban and rural areas in Europe. Using data from a large-scale survey conducted during the pandemic, we identify an indirect effect of occupation on migration intentions through preferences for teleworking. However, we do not find evidence of a direct relationship between occupation and teleworking. We term this phenomenon the “teleworking paradox”. To explain the paradox, we propose and test two mechanisms: economic agglomeration and health amenities. These mechanisms predict how workers in different occupations interact differently with place-specific factors. While evidence for the health amenity explanation is somewhat stronger than for the agglomeration mechanism, it remains mixed. Our findings suggest that the pandemic is unlikely to significantly narrow urban–rural disparities in Europe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

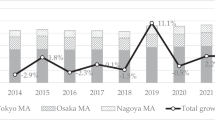

During the pandemic, an urban exodus from metropolitan to rural areas was—at least temporarily—observed in Japan, Spain, Sweden, the UK, and the other countries (González‐Leonardo et al. 2022; Vogiazides and Kawalerowicz 2023). This phenomenon led some to ponder whether this population movement would ignite a rural revival and foster a new urban way of life (González‐Leonardo et al. 2022; Sassen and Kourtit 2021; Wolff and Mykhnenko 2023; Bănică et al. 2024).Footnote 1

Although the issue of mobility has a clear economic dimension, many existing empirical studies, however, have largely overlooked this crucial aspect, focussing instead on the spatial dispersion consequences from a predominantly demographic perspective. For example, the study by González‐Leonardo et al. (2022) has focused mainly on people's age structure. Due to data limitations, the impact of education and other labour market characteristics of movers remained largely unexplored. Similarly, a social media analysis by Rowe et al. (2023) centred on the durability of the spatial movement without addressing the roles of personal characteristics. While occupations, education levels, and entrepreneurial activities were examined in Vogiazides and Kawalerowicz (2023) and Low et al. (2023), both studies did not investigate the distributional implications of population movement in spatial terms. Likewise, although many studies have examined income inequality during the pandemic (e.g. Adams-Prassl et al. 2020; Bonacini et al. 2021; Blundell et al. 2022), the spatial dimension remain under-explored. In other words, there is a notable lack of empirical analysis on how population movements influence regional inequalities. Consequently, the (spatial) distributional impacts of pandemic-related mechanisms, such as remote working and amenity migration, remain largely unknown.

This paper seeks to address this knowledge gap by examining how the possibility or trend of teleworking, enabled by digitalisation and accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, may influence residential mobility between rural and urban regions. Since the primary driver of rural–urban inequality lies in their distinct regional economies, we focus on individuals’ intentions to move and pose the question: to what extent does teleworking shape people’s location preferences in the context of the pandemic?

Answering this question has significant implications for rural–urban disparities. For instance, if most intended movers are well-endowed with human and financial capital, the urban–rural gap is likely to narrow (Zarifa et al. 2019). However, motivations for migration are diverse, and individuals with varying socioeconomic characteristics respond differently to place-based factors (Sagar 2012). Notably, the option to work remotely has proven particularly appealing to skilled workers (Wheatley 2021). This suggests that, if work culture and telecommunication infrastructure support such opportunities, skilled workers may be more inclined to avoid the high living costs of cities (Ramani and Bloom 2021). Such movement could spark a new demographic and economic cascade benefiting rural regions. Nevertheless, the scale of this shift will depend on the relative size of different demographic groups and other region-specific socioeconomic factors. In this context, our analysis seeks to examine the complex interplay between individual and place-based dynamics at the intersection of rurality and urbanity.

In so doing, we move beyond prior research by explicitly addressing occupational heterogeneity in our analysis. Migration motivations are inherently diverse. When examining population movements triggered by the pandemic, existing studies often assume that the urban-to-rural ‘exodus’ was primarily driven by the pandemic itself. This approach overlooks key socioeconomic differences, place-based determinants (Adams-Prassl et al. 2020), and possible selection effects arising from these heterogeneities. In this study, we investigate the potential impact of teleworking while accounting for these critical variations.

The following sections review relevant literature and present our research hypotheses. We then outline our methodological approach, empirical models, and data. Subsequently, we report and discuss the descriptive and estimation results. Finally, the paper concludes with a discussion of the broader implications of our findings.

2 Pandemic-induced social–technical cascades and the new urban world

Cities provide job opportunities and various amenities, including leisure and recreation facilities, as well as essential services such as healthcare and education. They cater to people's needs and attract those who can maximise their well-being by living in urban areas. However, the pandemic has redefined these needs and reshaped the perceived value of urban amenities. Decision to relocate now hinges on what a city can offer and the demographic diversity of potential migrants.

Preferences for urban amenities vary widely, making cities with attractive characteristics particularly valuable to specific groups (Storper and Scott 2009). People do not distribute randomly across space; they tend to cluster, with differing propensities for migration. A key condition for rural–urban rebalancing is whether pandemic risks influence migration intentions. The potential for telecommuting plays a pivotal role in these decisions, particularly in the context of the pandemic (Ramani and Bloom 2021).

Due to confinement measures, many individuals converted their homes into makeshift offices during the pandemic. While this transition often disrupted work–life balance and reduced job satisfaction, teleworking also offered flexibility, allowing employees to visit their physical workplace less frequently (Bellmann and Hübler 2021). Nevertheless, certain sectors, such as hospitality, require physical presence due to limited digitalisation, making migration contingent on occupation. Office workers, in particular, are more likely to adopt remote working and, consequently, consider urban-to-rural migration. This also applies to individuals in rural areas who previously desired urban amenities but were tied to cities to work. With telecommuting now an option, these individuals may be more inclined to relocate to more rural areas if their jobs permit.

Accordingly, we hypothesise that the intention to move is related to teleworking and that people with an office job are more likely to move to rural areas. However, while the pandemic may drive people away from cities (Wolff and Mykhnenko 2023), the superior availability of healthcare amenities in urban areas could motivate them to stay (Hamidi et al. 2020). The net effect of these opposite forces remains ambiguous and is ultimately an empirical question.

3 Data

The data are based on Flash Eurobarometer, a one-off short survey administered by the European Commission (2022). The original dataset encompasses residents of the 27 EU Member States. Approximately 1000 individuals were randomly sampled and phone-interviewed in each country, except for Cyprus, Luxembourg, and Malta, where about 500 individuals were sampled. Interviews were conducted between April 9 and April 18, 2021, during a period when the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases was subsiding but remained high in some countries. Although large-scale vaccination programs were announced or introduced during the interview period, restrictions such as partial lockdowns were still in place in some areas, and many people remained uncertain about the development and impacts of the pandemic. In total, 18,324 individuals from 22 EU member states were included in our analysis. Bulgaria, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Slovenia were not represented due to missing values in Eurostat or incoherent definition of geographical units between Eurostat, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, and Eurobarometer; merging various variables for some countries for further analysis was not possible in those countries.Footnote 2

Motivations for urban-to-rural migration are diverse, necessitating measurements that capture these varying drivers. In our analysis, we focus on people's preference for teleworking, while using health consciousness and affinity for the natural environment as control variables. Shortly after the pandemic outbreak, health concerns became a top priority, with many individuals relocating to avoid the disease. As the public health crisis unfolded and confinement measures were implemented, people began to reflect on the value of social connections, career priorities, and physical well-being—factors that could be partially supported by public amenities such as healthcare facilities. However, appreciation for rural environments is not universal and plays a critical role in migration decisions (Balcar and Šulák 2021). For example, new urban housing developments in peripheral areas with good access to open spaces and leisure facilities can serve as substitutes for natural amenities typically found in rural areas (Rybnikova et al. 2023). Therefore, we anticipate that health concerns and affinity for the natural environment are essential covariates influencing migration intentions during the pandemic.

In this study, the three measurement variables are ordinal: ‘much more likely,’ ‘somewhat more likely,’ ‘neither more nor less likely,’ ‘somewhat less likely,’ and ‘much less likely’. The scale of the variables is adjusted such that a higher number means that a person is more likely to work from home, to visit nature (a proxy for affinity with the natural environment), and less likely to use public transport after COVID (a proxy for health consciousness). To make the regression model less dense, we dichotomise these variables. A variable takes the value 1 if respondents answer much more likely or somewhat more likely and 0 otherwise. We also include some demographic and COVID-related covariates, more specifically: age, gender, a proxy for education levels (less than 15 years old, between 16 and 19, 20 and older, still studying, never been in full-time),Footnote 3 migrant backgrounds (based on nationalities and permanent resident status), and household size (1, 2, 3, and 4 or above).

The dependent variable (migrate) is an ordinal variable on a 5-point Likert scale: ‘much more likely,’ ‘somewhat more likely,’ ‘neither more nor less likely,’ ‘somewhat less likely,’ and ‘much less likely’. The scale of the variables is adjusted such that a higher number means that a person is more likely to migrate. The direction of population movements depends on people's location. Specifically, urban-to-rural migration is relevant only for people living in urban areas, and rural-to-urban migration is relevant only for people living in rural areas. Therefore, we model these decisions separately using only relevant observations in the regression models.

Several other country or regional level variables are included to account for people's mobility decisions. This includes the number of days that a country had been in lockdown. The data are from the Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker. We have used other stringency measures, but they do not have substantially different impacts. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control has country and age specific statistics on the 14-day notification rate of new COVID-19 cases. We classify people’s COVID risk based on the age variable from the survey. Some other related variables from Eurostat are also included: GDP, population size, density, medical doctors per 1000 persons in a region, internet coverage (in %) in the concerned country. We have used the number of hospital beds per capita in a region in previous analysis, but the variable contains more missing values, and the measure is sensitive to the COVID situation of the countries.Footnote 4 Location (e.g. large towns, small- and middle-sized towns, rural areas, remote areas) are also considered in the analysis. The definition, unit, sources, and summary statistics of these variables are reported in Table 1.

4 Results

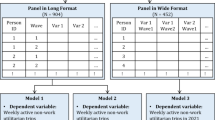

Since the direction of movement depends on the location of the respondents, we divide the sample into two groups: rural and urban. For individuals living in urban areas, the question was about their intentions to move to a more rural area. For individuals living in rural areas, the question was about their intentions to move to a more urban area. We have reversed the scale, such that a higher number means a greater intention to move.

Table 2 reports findings related to the relationship between intentions of movement and remote working. Workers who indicated that they would be more likely to work from home are also more likely to relocate from an urban to a more rural area after the pandemic. The odds ratio of the corresponding coefficients is 1.21 (based on Model 1), meaning that this group of people, on average, are about 20% more likely to move than people who are not more likely to telework. This finding echoes two recent studies by Ramani and Bloom (2021) and Jansen et al. (2024). The result is also consistent with a major finding in the literature on the suburbanisation debate before the pandemic (e.g. Zhu 2013), that the possibility of teleworking drives people to suburban areas to avoid high living costs in the urban core. The same conclusion holds in the presence of regional fixed effects.

Occupation is then added to the baseline model. A similar pattern is identified. People’s intentions to telework are positively associated with their movement intentions. However, our model does not find any statistically significant relationship between occupations and movement intentions. The same holds even when we account for potential ecological fallacies related to regional and country level characteristics (i.e. COVID risks and days in lockdown) using multilevel models.

The coefficients of other control variables carry the expected signs. For example, people who are fond of nature are more willing to move to rural areas. People at greater risk of getting COVID also have a greater interest in moving. When the COVID pandemic was still rampant, many media reports showed that people flocked to rural areas and stayed in their family homes or second houses (Halfacree 2024). The same fear and exposure to the news may trigger thoughts about moving to the countryside. In terms of demographic features, the quadratic relationship between age and intentions suggests that the intention to relocate to rural areas decreases with age (see Fig. 3 in the Appendix). Women are less likely to move than men. However, there is no discernible pattern regarding migrant background, education levels, household size, or location. Overall, the findings suggest that a rural revival, at least in demographic and socioeconomic terms, is highly unlikely, as no strong, favourable relationships can be identified from our models.

How about potential movements from rural to urban areas? The possibility of working from home does not have an apparent effect on migration intentions (Models 4 to 6). However, manual workers, craftsmen, shop owners, or self-employed professionals display a lower intention to move than office workers such as civil servants and clerks, as well as non-office workers such as salespersons and nurses. In terms of demographic structure, younger and older people (up to the age of 70) tend to stay (see Fig. 4 in the Appendix). The pattern for the younger people is counterintuitive, but the effect is close to zero. Again, educational levels do not predict movement intentions, whether occupations are controlled for or not. Considering the bi-directional movements between urban and rural areas, our analysis suggests that there is a discernible net movement from rural regions to cities among white-collar workers, including people occupying a management position. Although self-employed professionals like lawyers and entrepreneurs would stay, rural areas, on net, may lose their commuting dwellers, which may further intensify suburbanisation and the divide between urban and rural areas, contradicting the rural revival hypothesis.

5 Preferences for teleworking

Previous regression results suggest that occupations do not have a direct impact on the intentions of urban to rural migration. However, if occupations have a major impact on the possibilities of teleworking, then controlling for work from home intentions can potentially bias the coefficients of the occupation variables when there is another unobserved factor influencing the intermediate variable (work from home) and mobility intentions at the same time, introducing a collider bias in the estimations (Morgan and Winship 2015). Although our focus is the association between remote working and movement intentions, the bias could have a major impact on the preliminary conclusion that highly skilled workers are not more likely to realise their opportunities. While some studies have found no strong relationship between teleworking and residential mobility (e.g. Muhammad et al. 2007; Biagetti et al. 2024), some studies have reported a positive relationship (e.g. Zhu 2013; Jansen et al. 2024), though the causal direction is not always clear (Kim et al. 2012). In this section, we examine the relationship between intentions to telework and occupations and see whether there is a need to refine the previous conclusions.

To gain a better idea about the profiles of the potential movers, who also prefer to telework, we regress the work from home variable against occupation, educational levels, household size, age, gender, locations (village, small or medium towns, and large towns), internet coverage in a (NUTS) region, and three connectivity related variables. The coding of the connectivity variables is based on three survey questions asking respondents whether they want more local bus, local train, and intercity train services (1 = Yes). Needs for improved services can be interpreted as lower perceived connectivity or high time costs, which can be related to the work from home intentions.

Model 1 uses a pooled sample of urban and rural workers in the estimation. As expected, in general, manual workers are less likely to work remotely when compared with officer workers. Workers living in places with better internet coverage are also more inclined to telework. People living in large towns or cities also show greater interest in doing so. Younger workers with more years of education (i.e. leaving their school after 19) also prefer to telework more often after the pandemic. Finally, the want of better intercity train services is positively associated with remote working. This finding may be driven by commuters.

Location heterogeneity may have an impact on the inclination to telework. Models 2 and 3 differentiate between urban workers and rural workers. Similar patterns emerge. Workers living in suburban areas and, most likely, third-tier cities display a strong preference for remote working, this may explain why wanting better intercity train services is positively associated with remote working. Workers living in remote areas have even less likely to consider remote working than people living in villages. The jobs that they have, and the choice of a rural life may have also explained their location choice in the first place.

Note that the work from home variable was asked only among workers. As the intentions to telework and the employment decisions are related, dropping observations from non-workers may introduce selection bias. We utilise the Heckman selection model to account for this potential selection effects. We model the working decision based on educational levels, household size, age, gender, migration backgrounds, and unit-level (NUTS) fixed effects, which account for regional level explanatory factors such as GDP level and conditions of the local labour markets. Estimation results are reported under Model 4 in Table 3. The findings are similar.

6 The teleworking paradox

Thus far, we have shown that intentions to move and to telework are positively related (Table 2). We have also found that skilled workers prefer to telework (Table 3). Both relationships have been reported by previous studies. However, when we regress movement intentions on occupation, we do not find any systematic relationships between education levels, occupations and movement intentions among urban dwellers but rural residents (see Table 7 in Appendix). In other words, while there is a trace of indirect effect from occupation to movement intentions via preferences for teleworking, evidence of the direct effect is absent among urban workers. We call this teleworking paradox (Fig. 1). We hypothesise that this can be due to aggregations of opposite effects between subgroups. This section tries to provide a place-based explanation to the paradox.

Movement considerations are related to the way individual characteristics interact with placed-specific factors. Workers at different urban locations exhibit distinct movement intentions. Aggregations of the geographical heterogeneities may explain why we do not see a direct relationship between occupation and mobility intentions. People occupying an advanced position in an organisation have the flexibility to work from home, but they can be more likely to benefit from staying in cities at the same time. There are two potential mechanisms that can explain the coexistence. The first one is related to economic agglomeration. Professionals may gain (more) from the agglomeration of business activities in cities. Besides a perceived prestige from clients and possibly themselves (Blumen 1998), the location advantages allow them to benefit from information and knowledge spillovers and to connect more easily with their business partners in the central business districts, or urban customers who usually earn higher salaries (Hartshorn and Muller 1989; Gong and Wheeler 2002; Yang et al. 2023). The second explanation could be related to amenities. To the professionals, higher living costs in cities is less of a concern. So long as they can afford the high living cost, health services become more important to this group, especially during the pandemic period. When the benefits of moving out of cities are low relative to their potential loss, and the incentives to stay close to cities are high, the intentions to telework would not materialise.

In contrast, for people working in service sectors (e.g. restaurants) in cities, unless their jobs are at risk and they consider changing their occupations, their possibilities to telework should be relatively low. They also have lower intentions to move to more rural areas, as the financial returns of their jobs depend on their urban locations and customer base (Gokan et al. 2022). In other words, there is an urban premium for this group of workers (Lee and Tse 2024). Since similar job positions in more rural areas are usually lower-paying, they should have lower intentions to move. To them, both intentions to move and the possibility to telework are low.

Finally, the main group of workers who would consider moving to more rural areas are office workers who can gain from more work flexibility and lower living costs outside the metropolitan areas. The incentive to move is higher among them, if the option of remote working is available to them. However, this also implies that they may maintain their jobs in suburban areas or nearby second-tier or third-tier cities, commuting less often but at a longer distance. The relatively large size of this group might explain why an average effect can still be discerned between teleworking and movement.

The above explanation has two testable implications. First, professional and non-office-based workers in larger cities are less likely to move than those living in smaller cities. Second, telework is a lesser concern for professional workers and non-office-based workers in their movement intentions. A high willingness is found mainly among office workers.

Estimation results using observations only from urban areas are reported in Table 4. Each model uses only a subgroup of workers. According to the estimation results, the possibility of teleworking is not a major concern for professionals (e.g. company directors, top management, lawyers, accountants) in their moving considerations. In contrast, workers who have an office job (e.g. office clerks, mid-level management, civil servants), the possibility to work from home is associated with a greater intention to move. However, we also find an association among non-office workers who do not self-identify themselves as manual workers. This group of people includes those working in the service industries (e.g. restaurants and hotels) and other consumption sectors (e.g. salespersons). The last finding is against the hypothesis. Although a higher statistical risk of getting COVID tends to keep them in cities, and places with more doctors per person tend to keep the professional workers there, the second effect is short of statistical significance. This may suggest that the mechanism related to health amenities is less important for this group of people.

We further restrict our samples to residents of specific geographical areas to test our place-based explanation, and particularly, the agglomeration effects. Information about the whereabouts of the respondents is limited in the data set. We differentiate people living in cities in the capital NUTS region from those in non-capital NUTS regions. This empirical approach does not mean that larger non-capital cities such as Frankfurt cannot enjoy an agglomeration effect. The comparison between capital and non-capital regions aims to overcome the impreciseness of the geographical information contained in the data set. But to address this concern, we create two alternative indicators. The first excludes NUTS regions with larger major cities in a region from the sample in order to maintain a steep gradient, which we label as “capital minus”.Footnote 5 The second treats regions with major cities as if a capital region, which we label as “capital plus”. Nevertheless, due to impreciseness of the information, the tests have limited power, and results should be interpreted as suggestive.

We first compare the mean values of the migration intention variable and of the proxy variable for health “amenity”, number of medical doctors per 1000 persons.Footnote 6 The results are reported in Table 5. As expected, the numbers of medical doctors per capita are higher in the capital regions. And as hypothesised, migration intentions for both types of workers in the capital regions are lower than those in non-capital regions. We also ran several multilevel ordered logistics regression models. Models 1 to 3 in Table 6 compare professional workers living in the capital NUTS regions versus other large towns in non-capital NUTS regions. The coefficients of various capital region indicators are not statistically significant, meaning that working professionals living in capital regions are not less likely to move when compared with their counterparts in other regions. However, the coefficient for the medical doctor variable is negative and statistically significant. The coefficient of the COVID risk variable is also positively related to migration intentions, suggesting that the amenities mechanism is more likely at work than the agglomeration mechanism.

When we look at non-office workers, the proxy for agglomeration has a negative and a statistically significant effect (Models 4 and 5), but COVID risks have no effects on movement intentions. Surprisingly, the coefficient of the medical doctor variable is positive. This is counterintuitive and contradicts the pattern behind the summary statistics shown in Table 5. To search for possible explanations, we look into the sample data behind the two regressions (Models 1 and 4). Using region as the unit of analysis, we plot the average migration intentions in the capital regions against the numbers of doctors per capita. We manage to replicate the patterns suggested by the regression models. The plots can be found in Fig. 2.Footnote 7 Without the OLS regression line imposed, the data points might suggest a negative relationship between the two variables. A closer look to the graph, the (actual) positive slope seems to be related to EL30 (Attica) and FI1B (Helsinki-Uusimaa). The two observations have the highest predicted leverage values, influencing the slope of the line. These two regions happen to have other larger cities within the metropolitan regions, for instance, Piraeus in Attica, and Espoo and Vantaa in Helsinki-Uusimaa. The impreciseness of the proxy may have contributed to the positive coefficients.

7 Discussion

Overall, despite the unexpected sign for the coefficient on a proxy for a subgroup, we find some supportive evidence to the place-based explanation. Our finding related to the skilled workers contradicts a major finding in the literature, which suggests that teleworking has a major impact on high-income workers (Dingel and Neiman 2020; however, see also Althoff et al. 2022). We found that digital technology does not seem to draw this group of people away from the urban world. One possible reason is that highly skilled workers benefit more from economic agglomeration occurring mainly in larger cities (Safirova 2002; Gokan et al. 2022). However, statistical evidence for this mechanism is weaker and we found slightly stronger evidence for the health amenities explanation. Recent empirical evidence suggests that the urban exodus is largely driven by health concerns (Wolff and Mykhnenko 2023). One implication of this finding is that the negative health externalities in densely populated urban regions may predict a centrifugal movement away from the urban centres. However, our statistical evidence suggests that health risks may act as a centripetal force for many urban dwellers. Although the health systems were stressed and overwhelmed during the peak periods, superior health infrastructure such as intensive care was more accessible in cities (Hamidi et al. 2020). This may explain why some people prefer to stay in cities despite a higher health risk during the pandemic.

7.1 Limitations

Despite the rich database, this study is subject to several limitations. First, our analysis relied on individuals' intentions (stated preferences) rather than their actual moving behaviour (revealed preferences) as the dependent variable. The focus on movement intentions is rather limited, as only some people may turn ideas into actions. In this way, our findings are likely to overstate the actual size of the impact. Given that the survey was conducted at the end of the first wave of the pandemic, our estimates may also overstate the true intentions to migrate, possibly influenced by the despair that many people experienced during the lockdown period. Based on our analysis, since the demographic impacts of COVID-19 appear to be mild, the actual impact on migration could be even smaller than reported here. At the European level, there are no official statistics available to assess the extent to which COVID-19 has ultimately triggered urban-to-rural migration. Therefore, our findings should be considered preliminary and suggestive. Future research may investigate the potential gap between intentions and actual behaviours. Furthermore, other important determinants that affect movement intentions are also missing. For example, owning a second house in rural areas should reduce moving costs, which can influence intentions. More detailed location and contextual data should also be used to test the agglomeration and amenities mechanisms more carefully.

Second, due to the time-sensitive nature of the topic and the constraints of conducting a phone-based survey during a pandemic with physical restrictions imposed by many national governments, some essential controls such as income and sectors were not included in the data set. Additionally, our research focussed on teleworking, and the related question was only asked to those who were employed during the survey period. Consequently, our findings should not directly be generalised to the broader population. Nevertheless, we believe that our findings are valuable, especially considering the broad geographic coverage of our sample and the scarcity of data and evidence on an important and burgeoning topic of remote working and rural–urban mobility. Our study offers a systematic approach to understanding people’s intentions to move and their implications to rural–urban disparities, which may be overstated by some media reports and studies.

8 Conclusion

The digitisation of work has likely reshaped the appeal of compact, high-density urban locations, influencing preferences for urban and rural living and shaping the future structure of cities. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated these transitions. In the wake of the health crisis, teleworking has gained greater acceptance and becomes increasingly common. For many, remote work—at least part of the week—has become the norm. These shifts have redefined the perceived value of various locations, prompting individuals to consider relocating from urban centres to peripheral or rural areas when they find rural living more appealing and rewarding.

This study contributes to the discussion on rural–urban rebalancing by exploring the potential mechanisms driving these changes. Notably, there has been limited discussion on how rural areas might benefit from population movements in the context of the pandemic. To shed further light on the issue, we examine a key mechanism associated with regional rebalancing: remote working. As individuals possess both human and financial capital, their mobility can profoundly impact the business and economic landscape of a region. However, our findings indicates that better endowed individuals tend to remain in cities. This suggests that the digitalisation of work may perpetuate rather than reduce economic disparities between urban and rural areas, aligning with conclusions from earlier studies (Lagakos 2020; Bonacini et al. 2021).

Our findings also show that individuals who engage in remote work are more inclined to move. Among those expressing interest in relocation, the majority are younger people or older adults in middle- or entry-level positions. Conversely, individuals in high-level management roles exhibit little interest in relocating to rural areas. This finding supports earlier research suggesting that inter-regional migration is unlikely to alleviate urban–rural imbalances (Fratesi and Percoco 2014), reinforcing our major conclusion.

Migration decisions are also influenced by place-based factors. Regions with superior economic, natural, and public amenities tend to attract people and migrants (Buch et al. 2014). This can explain why the availability of health infrastructure has become a critical determinant of population flows during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, enhanced information and communication technology (ICT) and transportation infrastructures can anchor populations in urban areas, limiting rural areas’ potential gains from the urban exodus.

While teleworking exerts some influence on migration from rural to urban areas, its impact is relatively small. Other place-based factors that align with individuals’ socioeconomic characteristics are equally, if not more, decisive. For example, professionals and business owners often show little interest in relocating, possibly because their businesses are deeply rooted in local environment. This may also explain why urban economic agglomeration retains capital and skilled workers who complement local assets. As detailed in the limitation section, these conclusions are tentative, and better data are required to confirm the conclusions. Based on our findings, a substantial transformation of Europe's spatial demographic landscape—such as a radically new rural–urban balance—is improbable.

Notes

The NUTS levels in the data set are primarily determined by the Barometer and are in different levels. Country-wide: Portugal; NUTS Level 1: Belgium, Cyprus, France, Germany; NUTS Level 2: Austria, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Italy, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Spain; NUTS Level 3: Croatia, Finland, Hungary, Luxembourg, Romania, Slovakia, Sweden.

The coding of the variable is based on the question: ‘How old were you when you stopped full-time education?’. This is the only questions in the survey which we can extract information about education levels.

We included the variables in some analysis. The hospital bed variable usually produces an opposite sign due to some region outliers. Relevant discussion related to the other measure, medical doctors per 1000 persons, variable can be found in text around Table 6.

This includes BE2 (Antwerp), DE2 (Munich), DE6 (Hamburg), DE7 (Frankfurt), ES51 (Catalonia), ITC4 (Milan), NL31 (Utrecht), NL33 (Rotterdam and the Hague). A major drawback of this alternative is the shrinkage of sample size. For the inclusive sample, we include Luxembourg (LU00).

As discussed in the method section, we tried hospital beds per capita as an alternative measure. The strange sign of the coefficients, which also discussed in text later, and the time-sensitive nature of the bed variable during the COVID time explain our choice.

The counterpart for the professional workers is in the Appendix (Fig 3).

References

Adams-Prassl A, Boneva T, Golin M, Rauh C (2020) Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: evidence from real time surveys. J Public Econ 189:104245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104245

Althoff L, Eckert F, Ganapati S, Walsh C (2022) The geography of remote work. Reg Sci Urban Econ 93:103770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2022.103770

Balcar J, Šulák J (2021) Urban environmental quality and out-migration intentions. Ann Reg Sci 66(3):579–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-020-01030-1

Bănică A, Pascariu GC, Kourtit K, Nijkamp P (2024) Unveiling core-periphery disparities through multidimensional spatial resilience maps. Ann Reg Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-024-01259-0

Bellmann L, Hübler O (2021) Working from home, job satisfaction and work–life balance–robust or heterogeneous links? Int J Manpow 42(3):424–441. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-10-2019-0458

Biagetti M, Croce G, Mariotti I, Rossi F, Scicchitano S (2024) The call of nature. Three post-pandemic scenarios about remote working in Milan. Futures 157:103337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2024.103337

Blumen O (1998) The spatial distribution of occupational prestige in metropolitan Tel Aviv. Area 30(4):343–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.1998.tb00079.x

Blundell R, Costa Dias M, Cribb J, Joyce R, Waters T, Wernham T, Xu X (2022) Inequality and the COVID-19 crisis in the United Kingdom. Annu Rev Econ 14:607–636. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-051520-030252

Bonacini L, Gallo G, Scicchitano S (2021) Working from home and income inequality: risks of a ‘new normal’ with COVID-19. J Popul Econ 34(1):303–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00800-7

Buch T, Hamann S, Niebuhr A, Rossen A (2014) What makes cities attractive? The determinants of urban labour migration in Germany. Urban Stud 51(9):1960–1978. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013499796

Celbis MG, Kourtit K, Nijkamp P (eds) (2023) Pandemic and the city. Springer, Cham

Commission E (2022) Flash eurobarometer 491. A long term vision for EU rural areas, Brussels. https://doi.org/10.2762/40647

Dingel JI, Neiman B (2020) How many jobs can be done at home? J Public Econ 189:104235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235

Fratesi U, Percoco M (2014) Selective migration, regional growth and convergence: evidence from Italy. Reg Stud 48(10):1650–1668. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.843162

Gokan T, Kichko S, Matheson J, Thisse JF (2022) How the rise of teleworking will reshape labor markets and cities. CESifo Working Paper, No. 9952, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich

Gong H, Wheeler JO (2002) The location and suburbanization of business and professional services in the Atlanta area. Growth Chang 33(3):341–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2257.00194

González-Leonardo M, Rowe F, Fresolone-Caparrós A (2022) Rural revival? The rise in internal migration to rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Who moved and where? J Rural Stud 96:332–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.11.006

Halfacree K (2024) Counterurbanisation in post-covid-19 times. Signifier of resurgent interest in rural space across the global North? J Rural Stud 110:103378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2024.103378

Hamidi S, Sabouri S, Ewing R (2020) Does density aggravate the COVID-19 pandemic? Early findings and lessons for planners. J Am Plann Assoc 86(4):495–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2020.1777891

Hartshorn TA, Muller PO (1989) Suburban downtowns and the transformation of metropolitan Atlanta’s business landscape. Urban Geogr 10(4):375–395. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.10.4.375

Jansen T, Ascani A, Faggian A, Palma A (2024) Remote work and location preferences: a study of post-pandemic trends in Italy. Ann Reg Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-024-01295-w

Kim SN, Mokhtarian PL, Ahn KH (2012) The Seoul of Alonso: new perspectives on telecommuting and residential location from South Korea. Urban Geogr 33(8):1163–1191. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.33.8.1163

Lagakos D (2020) Urban-rural gaps in the developing world: does internal migration offer opportunities? J Econ Perspect 34(3):174–192. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.34.3.174

Lee K, Tse CY (2024) Amenities and wage premiums: the role of services. Ann Reg Sci 72(1):37–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-022-01188-w

Low SA, Rahe ML, Van Leuven AJ (2023) Has COVID-19 made rural areas more attractive places to live? Survey evidence from Northwest Missouri. Reg Sci Policy Pract 15(3):520–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12543

Morgan SL, Winship C (2015) Counterfactuals and causal inference. Cambridge University Press, New York

Muhammad S, Ottens HFL, Ettema D, de Jong T (2007) Telecommuting and residential locational preferences: a case study of the Netherlands. J Housing Built Environ 22:339–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-007-9088-3

Ramani A, Bloom N (2021) The donut effect of COVID-19 on cities (No. w28876). National Bureau of Economic Research

Rowe F, Calafiore A, Arribas-Bel D, Samardzhiev K, Fleischmann M (2023) Urban exodus? Understanding human mobility in Britain during the COVID-19 pandemic using Meta-Facebook data. Popul Space Place 29(1):e2637. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2637

Rybnikova N, Broitman D, Czamanski D (2023) Initial signs of post-covid-19 physical structures of cities in Israel. Lett Spat Resour Sci 16:25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-023-00346-8

Safirova E (2002) Telecommuting, traffic congestion, and agglomeration: a general equilibrium model. J Urban Econ 52(1):26–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0094-1190(02)00016-5

Sager L (2012) Residential segregation and socioeconomic neighbourhood sorting: evidence at the micro-neighbourhood level for migrant groups in Germany. Urban Stud 49(12):2617–2632. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011429487

Sassen S, Kourtit K (2021) A post-corona perspective for smart cities: ‘should I stay or should I go?’ Sustainability 13(17):9988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179988

Storper M, Scott AJ (2009) Rethinking human capital, creativity and urban growth. J Econ Geogr 9(2):147–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn052

Vogiazides L, Kawalerowicz J (2023) Internal migration in the time of Covid: Who moves out of the inner city of Stockholm and where do they go? Popul Space Place 29(4):e41. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2641

Wheatley D (2021) Workplace location and the quality of work: the case of urban-based workers in the UK. Urban Stud 58(11):2233–2257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020911887

Wolff M, Mykhnenko V (2023) COVID-19 as a game-changer? The impact of the pandemic on urban trajectories. Cities 134:104162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.104162

Wong PH, Kourtit K, Nijkamp P (2024) Pandemetrics: modelling pandemic impacts in space. Lett Spat Resour Sci 17(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-023-00368-2

Yang FF, Yeh AG, Wang X, Yi H, Chen Z (2023) State-market dynamics of central business district (CBD) development in Chinese cities–an anchor-firm perspective. Cities 143:104622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104622

Zarifa D, Seward B, Milian RP (2019) Location, location, location: examining the rural-urban skills gap in Canada. J Rural Stud 72:252–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.10.032

Zhu P (2013) Telecommuting, household commute and location choice. Urban Stud 50(12):2441–2459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012474520

Acknowledgements

Peter Nijkamp and Karima Kourtit acknowledge a grant from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme, under grant agreement No 101004627. Karima Kourtit acknowledges support from the CITY FOCUS project (CF23/27.07.2023) facilitated by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan for Romania (PNRR-III-C9-2023-18/Comp9/Inv8) and supported by the EU NextGeneration programme.

Funding

Horizon 2020, 101004627, Peter Nijkamp, Ministerul Cercetării şi Inovării, PNRR-III-C9-2023-18/Comp9/Inv8, Karima Kourtit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, PH., Kourtit, K. & Nijkamp, P. The teleworking paradox: the geography of residential mobility of workers in pandemic times. Ann Reg Sci 74, 39 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-025-01368-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-025-01368-4