Abstract

Purpose

To estimate long-term prognosis of chemosensory dysfunctions among patients recovering from COVID-19 disease.

Methods

Between April 2020 and July 2022, we conducted a prospective, observational study enrolling 48 patients who experienced smell and/or taste dysfunction during the acute-phase of COVID-19. Patients were evaluated for chemosensory function up to 24 months after disease onset.

Results

During the acute-phase of COVID-19, 80% of patients reported anosmia, 15% hyposmia, 63% ageusia, and 33% hypogeusia. At two years’ follow-up, 53% still experienced smell impairment, and 42% suffered from taste impairment. Moreover, 63% of patients who reported parosmia remained with olfactory disturbance. Interestingly, we found a negative correlation between visual analogue scale scores for smell and taste impairments during the acute-phase of COVID-19 and the likelihood of long-term recovery.

Conclusion

Our study sheds light on the natural history and long-term follow-up of chemosensory dysfunction in patients recovering from COVID-19 disease. Most patients who initially suffered from smell and/or taste disturbance did not reach full recovery after 2 years follow-up. The severity of impairment may serve as a prognostic indicator for full recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), also known as COVID-19, was initially reported in December 2019. In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced COVID-19 as a pandemic. By April 2024, the WHO had registered over 775 million confirmed cases and over 7 million confirmed deaths worldwide due to COVID-19 [1].

The clinical manifestation of acute COVID-19 can range from asymptomatic to mild flu-like symptoms such as cough, myalgia, fatigue, and fever, and severe disease with respiratory distress and multi-organ failure [2]. Although this virus typically causes respiratory symptoms, it can also have neurological manifestations, including impairment of the sense of smell and taste. Moreover, smell and taste dysfunction are consistently reported among the most common complaints among patients [3]. Anosmia, the loss of smell, and ageusia, the loss of taste, have been proposed as important tools of measure for clinical triage [4]. The prevalence of chemosensory dysfunction was found to be similar in both vaccinated and unvaccinated, suggesting that symptoms such as anosmia and ageusia can potentially be valuable as diagnostic markers for suspecting COVID‐19, regardless of vaccination status [5].

Five variants of SARS-CoV-2, known as Variants of Concern (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron), have been identified to date, and all of them have been associated with chemosensory dysfunction [6,7,8,9,10]. Since March 2023, these definitions have changed to “variants of interest” and “variants under monitoring”.

The persistence of symptoms after a COVID-19 infection, known as long-COVID, is a phenomenon in which symptoms continue for an extended period of time after the acute disease [11, 12]. The pathophysiology of long-COVID is not fully understood, but disturbances of taste and smell appear to be prominent symptoms [5, 11, 13]. Long-COVID can significantly impair the quality of life for some individuals and is considered an emerging pandemic concern [12].

Given the global prevalence of COVID-19, it is important to comprehend the long-term persistence of chemosensory dysfunctions. While anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients have been the subject of numerous studies, most of these studies have only analyzed these symptoms up to a few months, and many have been retrospective. In light of this, our prospective study aims to investigate the long-term prognosis of chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients and to estimate the recovery rate among these patients from the early stages of the pandemic.

Methods

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Rabin Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB# RMC-20-0223). All patients signed their written informed consent to participate.

Study design and participants

A prospective observational study from April 2020 to July 2022 consisted of 48 patients with confirmed COVID-19 via nasopharyngeal swab RT-PCR test. The study population consisted of adults aged 18 years or older who experienced either anosmia, hyposmia, ageusia, or hypogeusia during the acute-phase. Exclusion criteria included limited follow-up data, previous chemosensory dysfunction, pregnancy, and other neurological disorders.

Initial assessment and data collection

Data was first collected through in-person medical history interviews and a thorough head and neck physical examination at our dedicated post-COVID-19 outpatient clinic. We collected demographic information and comprehensive clinical information on COVID-19 infection.

Olfactory and gustatory evaluation

Smell and taste dysfunctions were evaluated throughout the follow-ups using the visual analog scale (VAS) [13, 14]. Patients were asked to rate their chemosensory impairment from 1 (anosmia/ageusia) to 10 (no impairment) prior to COVID-19 infection, during the disease, and throughout the follow-up.

Follow-up timeline

In our research, we methodically structured the follow-up process into specific time frames, which we refer to as Checkpoint-1, Checkpoint-2, and Checkpoint-3.

At Checkpoint-1 in our post-COVID-19 outpatient clinic, patients underwent initial evaluations, on average two months post-infection (62 ± 34 days). During this stage, patients reported chemosensory impairments during the acute-phase of COVID-19. Subsequent follow-ups were performed through online questionnaires. Checkpoint-2 was scheduled for 9 months post-infection (mean 266 ± 72 days). At Checkpoint-3, we re-evaluated only patients who had not fully recovered from chemosensory dysfunction. This evaluation occurred 24 months after the initial infection (mean 678 ± 74 days).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 26. Continuous variables were compared using the Student T-test for normally distributed variables and Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables and are presented as means ± standard deviations. Recovery rates based on VAS scores were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Categorical variables are presented as n (%).

Results

A total of 48 patients with COVID-19 infection and chemosensory dysfunction were initially evaluated. Eight patients were excluded due to incomplete follow-up or insufficient data. Of the remaining 40 patients, 19 were males (47.5%) and 21 were females (52.5%), with a mean age of 51 ± 12.6 years.

Demographic and clinical features of all patients included in the cohort are presented in Table 1. Fifteen patients (37.5%) required hospitalization, with a mean stay of 11 ± 12.1 days of hospitalization and a median of 6.5 days. Supportive oxygen therapy was administered to 2 patients, and one other patient required intubation owing to respiratory failure.

Our study focused on patients who reported chemosensory dysfunction during the acute COVID-19 infection. Thirty-six patients (90%) indicated concurrent disturbances in both olfactory and gustatory functions, two patients (5%) indicated only olfactory disturbances, and two patients (5%) reported only gustatory impairment. Other common symptoms were malaise, fever, cough, and headaches.

Evaluation of the olfactory impairment

Retrospective inquiries about smell impairment during the acute-phase of the disease and prior to infection were conducted among all patients (Table 2).

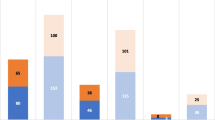

The mean VAS score for olfactory function prior to the disease was 9.87 ± 0.47, while the mean score during the acute-phase was 1.58 ± 1.62 (Fig. 1a). Anosmia was reported in 80% of cases (32/40), while hyposmia was reported in 15% of cases (6/40). Only two patients did not experience smell but merely taste impairment (5%).

It is worth mentioning that in 47% of cases (18/38), smell impairment was the initial symptom of COVID-19 infection. However, in 13% (5/38), smell dysfunction appeared more than 7 days after the onset of other symptoms. In 47% of cases, the onset of smell dysfunction was abrupt (18/38).

The median duration until improvement in smell function was 10 days (ranging from 3 to 180 days). During the follow-up period, the mean VAS score for smell was 7.03 ± 3.15 at the first follow-up meeting and 7.91 ± 2.63 at Checkpoint-2 (Fig. 1a). After 12 months, two patients were lost to follow-up. The mean VAS score at Checkpoint-3 was 8.43 ± 2.58 (Fig. 1a). While 92% of patients (33/36) demonstrated some level of recovery in their ability to smell, less than half (47%, 17/36) achieved full recovery to their baseline olfactory function by the end of the follow-up period.

Patients presenting with a VAS score ≥ 7 during the acute-phase of COVID-19, indicative of mild hyposmia, demonstrated a persistent olfactory disturbance. Meanwhile, those with a VAS score < 7, such as those with anosmia or severe hyposmia, largely exhibited promising signs of partial or total recovery (p < 0.01 Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed). Specifically, the mean VAS score during the acute-phase for patients who recovered was 1.21 ± 0.78, suggesting severe initial olfactory impairment. In contrast, the mean VAS score during the acute-phase for patients who showed no signs of recovery was 5.33 ± 3.79, indicating milder initial symptoms (p < 0.01, Mann–Whitney U test, two-tailed, Fig. 1b). Additionally, the group of patients who achieved complete recovery demonstrated the most substantial improvement across all follow-up periods.

Interestingly, 20% of patients (8/40) reported parosmia, a distortion or misinterpretation of the perception of smell. Of them only three (37.5%) had fully recovered by the end of the follow-up period.

Evaluation of the gustatory impairment

Additionally, all patients were retrospectively surveyed about their taste impairment before COVID-19 infection and during the acute-phase (Table 3), with mean VAS of gustatory impairment 9.92 ± 0.36 and 2.42 ± 2.4, respectively.

Gustatory impairment was reported by 95% of patients (38/40), ageusia in 62.5% (25/40), and hypogeusia in 32.5% (13/40). In all cases, loss of taste emerged concurrently with the earliest symptoms of COVID-19 infection.

The median time until improvement in gustatory function was 11 days (ranging from 3 to 45 days). The mean score for gustatory function consistently improved during the follow-up period, from 8.14 ± 2.61 at Checkpoint-1 to 8.33 ± 2.16 at Checkpoint-2, and 8.73 ± 2.64 at Checkpoint-3 (Fig. 2a). Most patients fully recovered (58%, 22/38 patients).

During the acute-phase of COVID-19, a VAS score ≥ 7, suggestive of mild hypogeusia, was notably linked to the prolonged persistence of taste impairment. In contrast, those with VAS scores < 7, representing ageusia or severe hypogeusia, tended to either partially or fully recover (p < 0.01 Fisher's exact test, two-tailed). Specifically, the mean VAS score during the acute-phase for patients who recovered was 1.97 ± 1.94, suggesting severe initial gustatory impairment. In contrast, the mean VAS score during the acute-phase for patients who showed no signs of recovery was 5.2 ± 3.56, indicating milder initial symptoms (p < 0.01, Mann–Whitney U test, two-tailed, Fig. 2b).

Discussion

Our prospective study of 40 patients explored the long-term recovery from COVID-19-related chemosensory dysfunction. Initially, 90% (36 patients) experienced disturbances in both smell and taste. Although most patients showed some improvement during long-term follow-up, only half achieved complete recovery of both senses.

The impact of COVID-19 on smell and taste has been widely documented in the literature. A meta-analysis found that the overall prevalence rates for smell and taste impairments were 51% and 47.5%, respectively [15]. Additionally, a recent survey in the US showed that 60.5% of COVID-19 patients reported smell impairment, and 58% reported taste impairment [16].

Our findings indicate a median chemosensory improvement time of less than 2 weeks, aligning with studies that show significant improvements within weeks [14, 17], although many experience persistent symptoms. Extended studies confirm that a substantial proportion of patients, ranging from 27–37%, continue to suffer from chemosensory impairment up to 1 year [18,19,20]. Few studies have evaluated the prevalence of chemosensory dysfunction over 24 months. In the 2-year study by Boscolo-Rizzo et al., among 62 patients with mild COVID-19, 13 subjects (21%) showed partial recovery, and 5 subjects (8.1%) reported no improvement [21]. Their subsequent study reported a 20.5% prevalence of chemosensory dysfunction among patients with mild COVID-19 after 2 years (18/88 patients), with one additional patient recovering within a 3-year period (17/88 patients) [22]. Schambeck et al., study of 44 healthcare workers with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 revealed that 11 participants (25%) experienced persistent disturbance in smell or taste after a median of 721 days. However, only 30 of 40 participants reported any change in taste or smell [23].

Importantly, while these studies are similar to ours, focusing on the long-term prognosis of chemosensory dysfunctions following COVID-19 recovery, they may suffer from selection bias due to concentrating on participants with mild symptoms. Additionally, in our study we estimate the long-term prognosis and the likelihood of recovery based on the initial severity of the self-reported impairments.

Hopkins et al. found that 93% of the subjects who reported parosmia continued to experience them after 6 months [24]. We observed a similar trend regarding parosmia: 63% of our patients who experienced parosmia continued to experience olfactory disturbances after 2-years. This finding is consistent with other studies that evaluate chemosensory dysfunction over periods ranging from 200 days up to 24 months [13, 23, 25], and it might suggest that parosmia could indicate an unfavorable prognosis.

Interestingly, our findings revealed a negative correlation between VAS scores for smell and taste impairment during the acute-phase of COVID-19 and long-term prognosis for recovery. Specifically, patients who presented with anosmia or severe hyposmia during the acute-phase displayed better recovery outcomes during follow-up than those with residual chemosensory function (VAS score ≥ 7). Similar to our findings, Iannuzzi et al. found a larger improvement in patients with anosmia compared with hyposmia subjects [26]. In contrast, Ohla et al. reported that patients who experienced a more significant reduction in their ability to smell were at a higher risk of long-term smell impairment, though the difference was numerically small [13].

Multiple theories explore the olfactory disturbance in COVID-19 without any universal consensus. The leading hypothesis suggests that disruptions arise from the olfactory epithelium, which is essential for smell perception and contains self-renewing cells [27]. Some studies highlight potential damage to non-neuronal cells [28], while others suggest direct damage to olfactory sensory neurons, altered neuron function due to immune responses, or other immune-mediated effects [29]. The impairment result from immune activation rather than the direct impact of the virus, possibly explaining the better recovery rates observed in our study for patients with acute-phase anosmia compared to those with milder hyposmia [29].

The different mechanisms of abrupt and long-COVID anosmia have yet to be deciphered. Biopsies from patients with persistent COVID-19 smell impairments showed ongoing inflammation in non-neural olfactory epithelial cells [28, 30], suggesting ongoing T-cell-mediated inflammation even after the virus had been cleared. Comparative analysis of long-COVID patients and infected hamsters revealed significant differences; human specimens showed prolonged T-cell infiltration, unlike the temporary immune response in hamsters, suggesting a distinct immunological response in long-COVID smell disorders. Yet, the samples often displayed an intact olfactory epithelium, challenging the idea that severe initial damage necessarily limits recovery [30].

Multiple studies suggest a possible correlation between a robust immune response and acute chemosensory impairment. Particularly, younger patients or those with fewer comorbidities seem more susceptible to acute-phase anosmia or ageusia [31,32,33]. Anosmia is also considered a favorable prognostic marker for milder COVID-19 progression [31, 34, 35].

Several studies have attempted to identify effective treatment interventions for chemosensory impairment. A Cochrane Living systematic review found no definitive results for interventions [36, 37]. Although there is currently no evidence supporting treatments to prevent persistent chemosensory dysfunctions, numerous trials are ongoing [36, 38].

Olfactory and gustatory functions are important in daily life, influencing diet, mate selection, and overall quality of life [39, 40]. Additionally, our sense of smell plays a crucial role in detecting life-threatening hazards such as toxic substances, fires, or gas leaks. Given that approximately 7% of COVID-19 patients might experience long-COVID anosmia [41, 42], 40% might have long-COVID hyposmia [41, 42], and 27% might suffer from hypogeusia [41], the global implications are enormous. With over 775 million reported cases to date, these chemosensory dysfunctions could potentially affect millions worldwide, leading to a substantial healthcare burden.

The present study has several limitations. First, our sample size was relatively small. Additionally, the evaluation of chemosensory dysfunction was based solely on subjective reports. These may not be as accurate as objective tests [43, 44] and could be susceptible to recall bias. However, some studies have suggested a positive correlation between subjective and objective methods [45].

Conclusions

Since the start of the pandemic, extensive research has explored anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients. However, most existing studies lack both prospective and long-term follow-up. Our research not only adds value to known literature but also sheds light on the natural history of chemosensory impairment through extended follow-up. After 2-years of follow-up, 53% of patients who initially presented with olfactory impairment during the acute-phase still reported smell disturbances. Additionally, by the end of the follow-up period, 42% of those who initially had gustatory impairment continued to experience taste disturbances.

Moreover, we identified a negative correlation between VAS scores for chemosensory impairment during the acute-phase of COVID-19 and the long-term prognosis for recovery. This leads to a central question: Can the severity of anosmia/ageusia during COVID-19 acute-phase predict long-COVID chemosensory disturbances? As new variants of COVID-19 continue to emerge, it is crucial to characterize and identify patients at high risk of enduring prolonged symptoms.

References

World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 1 May 2024

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X et al (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (London, England) 395:497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

Saniasiaya J, Islam MA, Abdullah B (2021) Prevalence of olfactory dysfunction in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis of 27,492 patients. Laryngoscope 131:865–878. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29286

Zahra SA, Iddawela S, Pillai K et al (2020) Can symptoms of anosmia and dysgeusia be diagnostic for COVID-19? Brain Behav 10:e01839. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1839

Vaira LA, De Vito A, Lechien JR et al (2022) New onset of smell and taste loss are common findings also in patients with symptomatic COVID-19 after complete vaccination. Laryngoscope 132:419–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29964

Luna-Muschi A, Borges IC, de Faria E et al (2022) Clinical features of COVID-19 by SARS-CoV-2 Gamma variant: a prospective cohort study of vaccinated and unvaccinated healthcare workers. J Infect 84:248–288

Hoang V-T, Colson P, Levasseur A et al (2021) Clinical outcomes in patients infected with different SARS-CoV-2 variants at one hospital during three phases of the COVID-19 epidemic in Marseille, France. Infect Genet Evol J Mol Epidemiol Evol Genet Infect Dis 95:105092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2021.105092

Krishnakumar HN, Momtaz DA, Sherwani A et al (2023) Pathogenesis and progression of anosmia and dysgeusia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Oto-rhino-laryngol 280:505–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-022-07689-w

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Cancela-Cilleruelo I, Rodríguez-Jiménez J et al (2022) Associated-onset symptoms and post-COVID-19 symptoms in hospitalized COVID-19 survivors infected with wuhan, alpha or delta SARS-CoV-2 variant. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11070725

Boscolo-Rizzo P, Tirelli G, Meloni P et al (2022) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related smell and taste impairment with widespread diffusion of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) Omicron variant. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 12:1273–1281. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22995

Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C et al (2021) More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 11:16144. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8

Michelen M, Manoharan L, Elkheir N et al (2021) Characterising long COVID: a living systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005427

Ohla K, Veldhuizen MG, Green T et al (2022) A follow-up on quantitative and qualitative olfactory dysfunction and other symptoms in patients recovering from COVID-19 smell loss. Rhinology 60:207–217. https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhin21.415

Ciofalo A, Cavaliere C, Masieri S et al (2022) Long-term subjective and objective assessment of smell and taste in COVID-19. Cells. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11050788

Kim JW, Han SC, Jo HD et al (2021) Regional and chronological variation of chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19: a meta-analysis. J Korean Med Sci 36:e40. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e40

Mitchell MB, Workman AD, Rathi VK, Bhattacharyya N (2023) Smell and taste loss associated with COVID-19 infection. Laryngoscope 133:2357–2361. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.30802

Hopkins C, Surda P, Whitehead E, Kumar BN (2020) Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic—an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 49:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-020-00423-8

Vaira LA, Salzano G, Le Bon SD et al (2022) Prevalence of persistent olfactory disorders in patients with COVID-19: a psychophysical case-control study with 1-year follow-up. Otolaryngol Neck Surg 167:183–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998211061511

Niklassen AS, Draf J, Huart C et al (2021) COVID-19: recovery from chemosensory dysfunction. a multicentre study on smell and taste. Laryngoscope 131:1095–1100. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29383

Boscolo-Rizzo P, Guida F, Polesel J et al (2022) Self-reported smell and taste recovery in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a one-year prospective study. Eur Arch Oto-rhino-laryngol 279:515–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-06839-w

Boscolo-Rizzo P, Hummel T, Invitto S et al (2023) Psychophysical assessment of olfactory and gustatory function in post-mild COVID-19 patients: a matched case-control study with 2-year follow-up. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 13:1864–1875. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.23148

Boscolo-Rizzo P, Hummel T, Spinato G et al (2024) Olfactory and gustatory function 3 years after mild COVID-19—a cohort psychophysical study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 150:79–81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2023.3603

Schambeck SE, Mateyka LM, Burrell T et al (2022) Two-year follow-up on chemosensory dysfunction and adaptive immune response after infection with SARS-CoV-2 in a cohort of 44 healthcare workers. Life (Basel, Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/life12101556

Hopkins C, Surda P, Vaira LA et al (2021) Six month follow-up of self-reported loss of smell during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rhinology 59:26–31. https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhin20.544

Almutairi DM, Almalki AH, Mirza AA et al (2022) Patterns of self-reported recovery from chemosensory dysfunction following SARS-CoV-2 infection: insights after 1 year of the pandemic. Acta Otolaryngol 142:333–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2022.2062047

Iannuzzi L, Salzo AE, Angarano G et al (2020) Gaining back what is lost: recovering the sense of smell in mild to moderate patients after COVID-19. Chem Senses 45:875–881. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjaa066

Choi R, Goldstein BJ (2018) Olfactory epithelium: cells, clinical disorders, and insights from an adult stem cell niche. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 3:35–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.135

Brann DH, Tsukahara T, Weinreb C et al (2020) Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. Sci Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc5801

Butowt R, Bilinska K, von Bartheld CS (2023) Olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19: new insights into the underlying mechanisms. Trends Neurosci 46:75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2022.11.003

Finlay JB, Brann DH, Abi Hachem R et al (2022) Persistent post-COVID-19 smell loss is associated with immune cell infiltration and altered gene expression in olfactory epithelium. Sci Transl Med 14:eadd0484. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.add0484

Talavera B, García-Azorín D, Martínez-Pías E et al (2020) Anosmia is associated with lower in-hospital mortality in COVID-19. J Neurol Sci 419:117163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2020.117163

Algahtani SN, Alzarroug AF, Alghamdi HK et al (2022) Investigation on the factors associated with the persistence of anosmia and ageusia in Saudi COVID-19 patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031047

Lee Y, Min P, Lee S, Kim SW (2020) Prevalence and duration of acute loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci 35:e174. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e174

Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Beckers E et al (2021) Prevalence and 6-month recovery of olfactory dysfunction: a multicentre study of 1363 COVID-19 patients. J Intern Med 290:451–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13209

Silu M, Mathur NP, Kumari R, Chaudhary P (2021) Correlation between anosmia and severity along with requirement of tocilizumab in COVID-19 patients. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 73:378–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-021-02679-6

Webster KE, O’Byrne L, MacKeith S et al (2022) Interventions for the prevention of persistent post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD013877. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013877.pub3

O’Byrne L, Webster KE, MacKeith S et al (2022) Interventions for the treatment of persistent post-COVID-19 olfactory dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD013876. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013876.pub3

Tsuchiya H (2023) Treatments of COVID-19-associated taste and saliva secretory disorders. Dent J. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11060140

Park JW, Wang X, Xu R-H (2022) Revealing the mystery of persistent smell loss in long COVID patients. Int J Biol Sci 18:4795–4808. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.73485

Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR et al (2020) Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Oto-rhino-laryngol 277:2251–2261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1

Boscolo-Rizzo P, Hummel T, Hopkins C et al (2021) High prevalence of long-term olfactory, gustatory, and chemesthesis dysfunction in post-COVID-19 patients: a matched case-control study with one-year follow-up using a comprehensive psychophysical evaluation. Rhinology 59:517–527. https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhin21.249

McWilliams MP, Coelho DH, Reiter ER, Costanzo RM (2022) Recovery from Covid-19 smell loss: two-years of follow up. Am J Otolaryngol 43:103607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103607

Vaira LA, Lechien JR, Khalife M et al (2021) Psychophysical evaluation of the olfactory function: European multicenter study on 774 COVID-19 patients. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10010062

Hannum ME, Ramirez VA, Lipson SJ et al (2020) Objective sensory testing methods reveal a higher prevalence of olfactory loss in COVID-19-positive patients compared to subjective methods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chem Senses 45:865–874. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjaa064

Nørgaard HJ, Fjaeldstad AW (2021) Differences in correlation between subjective and measured olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions after initial ear, nose and throat evaluation. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 25:e563–e569. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1722249

Funding

Open access funding provided by Tel Aviv University. No funding was procured for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boldes, T., Ritter, A., Soudry, E. et al. The long-term effect of COVID-19 infection on olfaction and taste; a prospective analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 281, 6001–6007 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-024-08827-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-024-08827-2