Abstract

This article analyses the effect of COVID-19 on the quality of employment in Colombia. Based on the construction of two job quality indexes, we estimate a pseudo-panel-ordered probit model correcting for measurement errors and the endogeneity of education. Depending on the job quality index, our results show that the probability of having a low-quality job increases between 1.6 and 27.8 percent points (p.p). In contrast, the probability of having a high-quality job decreases by 8.3 and 21.4 p.p. due to COVID-19. Also, people with higher levels of education are more likely to have high-quality jobs in Colombia; being a Venezuelan immigrant reduces the probability of having quality jobs, and being a woman has different effects depending on the index.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

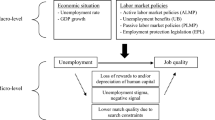

The effects of COVID-19 on employment have been disastrous. Actions to slow the spread of the pandemic, such as containment and quarantines, have led to a drop in jobs worldwide. Companies in service-related sectors that could use technological tools resorted to strategies such as teleworking or working from home. These measures have impacted quality of life and employment, among other variables.

In Colombia, as in other countries, employment has been reduced, and unemployment has increased due to the effects of COVID-19. According to the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE in Spanish), the employment rate fell to 49.8% in 2020 compared to 56.6% in 2019. Results imply that, in total, 2.4 million Colombians lost their jobs during 2020. Conversely, the unemployment rate increased by 5.6 p.p. in 2020 compared to 2019 (16.1% vs. 10.5%), which increased to 1.4 million unemployed. However, the adverse effects observed in the labour market were not equal for all Colombians, widening the gap mainly among young people (Mora et al. 2021; Farné & Sanín 2021) between rural and urban areas (Becerra et al. 2021) and between sectors (Farné & Sanín 2021) and in turn there was a drop of slightly more than 10% in the number of hours worked, so that on average Colombian workers spent in their jobs 4.4 h less per week than they did before the pandemic (Alfaro et al. 2022). Isaza-Castro (2021) shows that the pandemic disproportionately affected occupations performed by women, such as those involving proximity and social interaction with other people. As women in Colombia are traditionally taking most of the households' reproductive work burden, including the care of children and older people, the pandemic had a disproportionate effect on female labour force participation, which recorded the lowest levels in more than two decades. Finally, Isaza-Castro concludes, "The crisis in Colombia has a face of young women" (p. 13).

No studies have analysed the effect of COVID-19 on the quality of employment in Colombia. Some analyses have shown that informal workers had less earnings (Becerra et al. 2021; Farné & Sanin 2021), and from this information, it is inferred that the quality of employment has been reduced.

At the Latin American level, Sehnbruch et al. (2020), using the Alkire and Foster method, analyse the quality of employment in Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay for 2015. The results show that 68.6% of Colombian workers suffer some deprivation of conditions that increase job quality. The synthetic index developed by Sehnbruch et al. (2020) also indicates that Chile, Uruguay, and Brazil have the best job quality indicators for this group of countries; Chile exhibits the best results, while Paraguay presents the worst consequences.

The main contribution of this paper is to analyse the effect of COVID-19 on the quality of employment in Colombia. Two indexes are used for this purpose. The first is an adaptation of the job quality index of Mora and Ulloa (2011), which includes wages, and the second is an adaptation of the index proposed by Arranz et al. (2018), which excludes wages. Although both indexes coincide in the use of hours worked, there are substantial differences, such as income (wages) information or the level of overeducation.

Our results show that COVID-19 hurt job quality and that workers with fewer years of education are less likely to have a high-quality job than those with more years of schooling. However, the results for women are inconclusive as different signs are obtained depending on the type of index used. Finally, Venezuelan immigrants are more likely to have lower job quality.

2 The Quality of Employment

In 2007, during the fourth seminar on quality of work measures, the International Labour Organization (ILO), the European Union (EU), and the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions compared the dimensions of their conceptual frameworks. As a result, they developed a new framework with an international approach to measuring job quality. It should be noted that the ILO's primary focus has been on the concept of “decent work.” In this sense, Arranz et al. (2016) argue that this concept represents more an expression of a political objective than something operational. Several years of discussion culminated in the publication of a handbook on concepts and definitions for more than 50 “decent work indicators” that could be used to monitor progress in implementing the "Decent Work Agenda" (ILO 2012).

The quality of employment must be based on objective factors, as pointed out by Slaughter (1993), Van Bastelaer and Hussman (2000), and Reinecke and Valenzuela (2000), since these are unalterable and do not depend on the individual's preferences or expectations (Bustamante & Arroyo 2008, p. 145).

Decent work is characterised as quality work, an attribute that replaces its productive and well-paid nature (Ermida-Uriarte 2001). The concept of decent work and job quality is highly interrelated. Job quality is defined as the set of factors linked to work that influence the economic, social, psychological, and health well-being of workers (Reinecke & Valenzuela 2000), these factors being the expression of objective characteristics dictated by labour institutions and by norms of economic, social, and political acceptance (Farné 2003). This concept also encompasses the personal and labour characteristics associated with the job they hold, which are transformed into capabilities that the individual values because they allow them to achieve a higher level of well-being (Sehnbruch et al. 2020).

For Weller and Roethlisberger (2011), the determinants of job quality are not only based on the quality of the job place, which is related to the productive process but also on additional aspects such as the institutional framework, which affects collective and labour relations and influences income, working hours, contractual status and the dynamics of participation, among others. According to Camacho et al. (2012), decent work focuses on the implications for the well-being of workers, while job quality focuses on the characteristics of jobs (wages, working hours, social benefits, type of contract, etc.).

Cassar and ETH-Zurich (2010) analyse the determinants of job satisfaction in Chile using official labour market data. Their results reveal that self-employed workers have higher job satisfaction when controlling for job protection and security measures.

For Spain, Dueñas et al. (2009) analyse the relative quality of employment in the Spanish Autonomous Communities by constructing a quality of employment index, identifying the most relevant factors that explain the regional differences observed and their evolution. Somarriba et al. (2010) analyse the factors that most influence the determination of job quality in the context of the EU. The results show that subjective indicators such as the perception of happiness at work or feeling well remunerated explain more than the indicators usually considered as the type of contract and the hours worked. Royuela and Suriñach (2013) examine the connection between productivity and work quality. The authors find that the quality of work is an extra factor in explaining productivity levels in sectors and regions in Spain. García-Serrano et al. (2017) developed and assessed an employment quality index depending on each worker's contract for Spain and Italy. According to the results, employment quality was broadly consistent from 2006 to 2014, with a modest gain at the beginning and a slight decline in the middle. Arranz et al. (2019) observe that countries with lower government involvement in the wage-bargaining process and the minimum wage system typically have higher employment standards.

Storer et al. (2020) estimate racial/ethnic inequalities in temporal characteristics of employment quality (insufficient work hours, on-call shifts, and last-minute cancelations) using employer–employee data from The Shift Project in the USA for the service sector.

Eisenberg-Guyot et al. (2020) created a multidimensional employment quality index in the USA. According to the results, respondents in low-EQ clusters tended to be more persons of color, less educated, and reported worse health.

Sehnbruch et al. (2020), using the Alkire and Foster method, analyse the quality of employment in Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay. Their index provides insights into vulnerable worker groups and factors of labour market deprivation, expanding the discussion to include variables like occupational status and job tenure. It reveals disparities in Latin America, with Chile performing best and Paraguay the worst. Additionally, it highlights significant job rotation issues in several countries and notes that low unemployment does not always correlate with low deprivation.

Lažetić (2020) examines the gender differences in a wide range of labour market outcomes, including income, skill utilisation, work autonomy, employment security, and work-life balance. The findings indicate that male higher education graduates earn larger starting salaries. However, women report superior skill utilisation, work autonomy, and job security regarding institutional factors that affect gender differences in work quality.

Camussi et al. (2021) find that while there is an upgrading trend at the average EU level (from 2011 to 2017), Italy presented a polarisation pattern toward lower-paid jobs. This pattern results from diverse trends happening in different parts of Italy. Whereas the central and northern regions are in charge of the rise in the proportion of employees in both low-quality and high-quality occupations, southern Italy was solely responsible for the increase in low-paying jobs.

The European Intrinsic Job Quality Index, created by Cascales (2021), is a new approach to evaluating a job's intrinsic elements. According to the findings, the Nordic model's member states perform best in intrinsic quality. Conversely, the nations with the lowest rankings follow the Southern European model (Italy, Greece, and Cyprus).

Bassanini et al. (2023) analyse how labour market concentration affects earnings and job security, contributing to employment quality. They find that a 10% rise in labour market concentration lowers the likelihood of landing a permanent job by 0.46% in France, 0.51% in Germany, and 2.34% in Portugal.

In the Colombian context, the quality of employment has been a topic of relevance and rapid expansion since the early 2000s. Thus, following the pioneering work of Farné (2003), different methods used in the construction of multidimensional indicators associated with the measurement of job quality can be observed, such as Farné and Vergara (2007); Mora and Ulloa (2011) To measure the quality of employment, the most widely used indicator in Colombia is the one proposed by Farné (2003). This indicator values salaried and self-employed workers differently and captures the effect of certain conditions on workers. However, other authors such as Mora and Ulloa (2011), Mora et al. (2016); Gómez et al. (2017), and Galvis et al. (2021) have used variations of Farné's (2003) index, applying statistical techniques such as Principal Component Analysis and Fuzzy Sets.

Mora and Ulloa (2011) discuss education's endogeneity effects on the job quality index. Results show that the quality of employment improved compared to 2001. Differences in job quality arise between men and women and between economic sectors and cities.

Using the Quality-of-Life Survey (2010) for Colombia, Lasso and Frasser (2015) found that 62.4% of Colombian jobs are considered to be of good quality. A working life cycle is supported by the concentration of higher-quality employment in the middle of the age distribution and the lower quality of occupations held by young people and senior citizens.

Bustamante and Arroyo (2008) and Arroyo et al. (2016) corroborate the presence of patterns of racial discrimination and spatial segregation in the quality of employment toward the Afro-descendant population in Cali, where Black workers are more likely to be in low-quality jobs.

Jiménez and Páez (2014) show that most workers earn up to a minimum wage, do not have employment contracts, have shorter workdays than the legal minimum, and are connected to the health care system.

Farné and Vergara (2015) find that the quality of employment improved slightly overall, which was caused by an increase in social security income and a decrease in underemployment per hour, which benefited independent workers more than other workers.

Gómez et al. (2017) calculate the Multidimensional Index of Employment Quality using Sen's functions and capacities approach and the fuzzy set method. They find that employees of giant corporations and those with advanced degrees have much better quality of work, and older persons are less likely to have high-quality jobs overall.

3 The Construction of the Quality of Employment Index

As Sehnbruch et al. (2020) point out, there needs to be more consensus in the literature on decent work, quality of work, and quality of employment. Thus, the terms are sometimes interchangeable in the literature, and much depends on institutions such as ILO, EU, OECD, and the IBD (p. 2). However, although the variables that explain job quality are unclear, there is some consensus that job security, employment conditions, and income helps explain job quality in developing countries (p. 2).

For this reason, this article presents two indicators, adapted to the information on employed persons in Colombia and whose source is the Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares, GEIH, which, in turn, is officially compiled by the Colombian National Administrative Department of Statistics, DANE.

Table 1 show the first indicator of job quality (JQIndex1) considers income (wages), forms of hiring, job security, and employment conditions as follows:

Thus, the type of hiring and social security affiliation account for job security while working hours explain the conditions of employment or work. Table 2 show the second employment quality index considers the following variables (JQIndex2):

It should be noted that the second index does not include income (Wages), which, due to the pandemic, was reduced during 2020. However, the government allocated resources for assistance such as “Ingreso solidario” (benefiting 3 million households with subsidies of 160,000 pesos per month) and value aggregated tax (VAT) reimbursement. It strengthened other assistance such as “Adulto Mayor,” “Familias en Acción,” and “Jóvenes en Acción.” Unlike other countries such as Spain, there are no specific questions to measure the mismatch in qualifications. Because of this, the overeducation index was calculated by comparing the level of education of the person with the average education of each sector (roughly one standard deviation) proposed by Mora et al. (2022) for the Venezuelan migrant population. Concerning the weights, Index 1, we follow Farné (2003, 2007) and Mora et al. (2011, 2016), while we follow Arranz et al. (2016, 2018, 2019) weights to compute Index 2.

Regardless of how job quality is calculated, an index is obtained, which takes values between 0 (no job quality) and 100 (total job quality). The index is subdivided into three thresholds: Low job quality for values between 0 and 60, Medium job quality for values between 61 and 80, and High job quality for values between 81 and 100. Different researchers calculated the first index in Colombia, and the results show values on average close to 60 points.

4 Methodology and Econometric Estimation

Given that the job quality index takes three values, High, Medium, and Low, then the following ordered probit model will be estimated:

where

In Eq. (1) (t),t is the index of job quality, ηi(t),t is the unobservable individual heterogeneity, the variable T is a time dummy variable that takes the value of 1 for April 2020 and zero in the other months. It should be noted that although COVID-19 arrived in Colombia in March, it was only in April that extraordinary measures were adopted to halt its advance (Ministerio de Salud de Colombia 2020); therefore, government intervention to reduce the effects of the virus on employment and job quality can only be analysed from that month onwards. The variable COVID-19 is a dichotomous variable that takes a value of one if the person had COVID-19 and zero otherwise.Footnote 1 Therefore, the statistical significance of T* COVID-19 shows the impact of COVID-19 on job quality over the period analysed (The counterfactual concerning the effect of COVID-19 will be those individuals who did not have COVID-19).

(t), has generally been composed of a set of exploratory variables of job quality such as education, male, marital status (married), and whether young (Mora 2011; 2016; Galvis et al. 2021; Castillo & Acosta 2018). In this article, education, sex, and Venezuelan will be considered.Footnote 2 Venezuelan migrants are significant in the Colombian labour market because migration affects the hours worked (Mora et al. 2023), and migrants experience more overeducation versus native workers (Mora et al. 2022).

Finally, \({\text{Control}}_{i\left(t\right),t}\) are control dummies for regional metropolitan areas, the economic sector, and occupational at one level (DANE 2022).

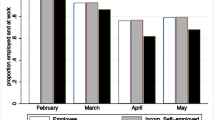

Two considerations should be made concerning the estimation of regression (1). The first is that subscript i(t), t refers to cross-sectional data of individuals that are different at each point in time. In principle, a three-year pool-type grouping could be sufficient if there were no changes in the unobservable individual heterogeneity, i(t), over t.Footnote 3 However, since COVID-19 generated substantial effects on the mental health of individuals in Colombia, it is not possible to guarantee that it will stay the same (Table 3 and Fig. 1). According to the GEIH data for 2020 and 2021 concerning how COVID-19 affected people, the following can be observed:

Table 3 shows that for all cohorts, the percentage of people who suffered stress, depression, or felt lonely increased, with the percentage of people aged 59 to 58 growing the most from one period to the next. The difference is around five p.p., and it is statistically significant. Concerning the perception of how COVID-19 affected income, the number of people who experienced a decrease in income increased by about 8% between 2020 and 2021, and the difference is statistically significant.

It can also be observed that COVID-19 not only produced more significant states of depression and anxiety but also had effects on Colombian households through the increase in the number of divorces, which has an impact on people’s marital status and what this could imply on their work performance, as can be seen in the following graph:

According to Fig. 1, the number of divorces increased by 27.88% between 2020 and 2021. All of the above will affect unobservable individual heterogeneity, and therefore, it is important to consider the latter.

For the above reasons, given that there is unobservable individual heterogeneity that changes over the years analysed, measurement errors will lead to inconsistent estimators, so the only way to consistently estimate the quality of employment is to estimate an ordered probit following the methodology for pseudo-panel data proposed by Deaton (1985) and extended by Moffit (1993) to the case of instrumental variables. This methodology has been used by Mora and Muro (2008) to model the probability of being informal in Colombia.

The second consideration is the endogeneity between education and job quality. As Mora and Ulloa (2011) point out, it is clear that more education leads to better job quality, and improvements in job quality lead individuals to demand more education. Thus, to obtain consistent and efficient estimators, an ordered probit model will be used by instrumenting education with cohort variables to correct for endogeneity and measurement errors.

5 Data and Variables

The data are taken from the “Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares,” GEIH, conducted by DANE for Colombia. Of the total number of employed persons, only salaried workers are considered. In addition, self-employed workers and employers are excluded. The latter is excluded because the type of contract does not apply to them. Most of them do not pay pension contributions (Galvis et al. 2021), and neither is overeducation a characteristic that restricts access to better jobs.

Because the GEIH sample consists of different observations in each period, it is not possible to follow the individual (Panel); for this reason, age cohorts present the information. Table 4 summarises the variables according to eight cohorts,

In Table 4, the number of observations is 328,295 across the eight cohorts. The first cohort, for example, groups individuals aged 18 to 23 in 2019 and ends with individuals aged 20 to 25 by 2021. The last cohort begins with individuals between the ages of 59 and 64 in 2019 and ends with individuals between the ages of 61 and 66 in 2022.

The average number of years of education is higher in the first cohorts than in the last. The percentage of employed men is slightly higher than that of women. The first cohorts have a lower proportion of married people, and the percentage of heads of household is also lower compared to the last cohorts.

The average number of years of education is higher in the first cohorts compared to the last ones. The percentage of employed men is slightly higher than that of women. The first cohorts have a lower proportion of married people and the percentage who are heads of household is also lower in these cohorts compared to the last cohorts. 10.4% of individuals suffered from stress because of COVID-19 and 17.4% felt that COVID-19 had a diminishing effect on income.

6 Results

As indicated above, Eq. (1) was estimated with panel pseudo-panel data instrumenting education and the interaction variable with dummies by cohort, which allows for correcting measurement errors and endogeneity.Footnote 4Footnote 5 Table (5) shows the marginal effects of low quality with the two job quality indices and shows that all variables are statistically significant.

The first column in Table 5 shows the marginal effects using the continuous job quality index one (JQIndex1) values. Results show that the pandemic adversely affects job quality and education, and being a man increases job quality. Finally, being a Venezuelan immigrant reduces job quality. All variables are statistically significant at 1%.

The results in Table 5 show that more education increases the probability of having a high-quality job in both estimations. For the first model (continuous), an additional year of education increases the probability of high quality. Using IV-Ordered Probit education increases by 2.4 p.p and by 5.6 p.p in the second model the probability of having high-quality jobs and reduces 4.4 p.p. and 5.5 p.p the probability of having low-quality jobs; these results are in line with what was found for Colombia by Mora and Ulloa (2011) and Lasso and Frasser (2015), among others.

We observe that the results of the impact of sex on job quality are different if we include/exclude wages and mismatch qualifications, and work schedules and family responsibilities are compatible. If we exclude these variables, COVID-19 impacts the job quality differently for women. The results may be explained by the she-cession effects of COVID-19 (Thoreau 2022): "The pandemic did not create new gender inequalities in the workforce, but it is noteworthy that it did substantially worsen existing inequalities" (Thoreau 2022, p.2).

Concerning the effects of COVID-19 on the quality of employment, it can be observed that, for the first index, which takes income into account, the probability of having a low-quality job increases by 1.6 p.p., while the probability of having a high-quality job decreases by 8.3 p.p. Concerning the second index, it can be observed that the probability of having a low-quality job increases by 27.8 p.p, while the probability of having a high-quality job decreases by 21.4 p.p

One possible explanation for these results is that income has a 40% weight on the index, and as can be seen, the perception of income increased from 23% in 2020 to 30% in 2021, which would partly explain the adverse effects of COVID-19 on job quality. It should also be noted that during the pandemic, there were many changes in contract flexibility because of COVID-19.

Regarding the second index, it should be noted that the compatibility between work and home activities went from 91.44% in 2019 to 66.99% in 2020 and 91.67% in 2021; health affiliation from 92.38% in 2019 to 91.99% in 2020 and 92.34% in 2021. In addition, the percentage of workers working more than 48 h per week decreased from 28.45% in 2019 to 25.48% in 2020 and 24.48% in 2021.

Finally, being a Venezuelan migrant increases 0.34 p.p. the probability of having quality jobs and reduces 0.21 p.p the probability of getting high-quality jobs. Results are the way of Mora et al. (2022), who find that Venezuelans are undereducated compared to natives and how migration affects the hours worked (Mora et al. 2023).

7 Conclusions

Several factors determine the quality of employment. Some are reflected in income, others in working time, the compatibility of work with the home, social security, and even over-education. Measuring it is not an easy task, and synthetic indicators have been developed into fuzzy sets for this purpose, but there is no single method for measuring it at the moment.

In Colombia, the quality of employment has been, on average, around low-quality jobs. The results found here are when income is considered to be around 60 points, which implies low- to medium-quality jobs.

The advent of COVID-19 affected people's health and generated a significant loss of jobs worldwide. It also affected the quality of jobs and the well-being of workers.

Our results show that the quality of employment declined due to COVID-19. Although we use different variables to compute the job quality, COVID-19 negatively affects job quality. In general, the pandemic increases the probability of having low-quality jobs and reduces the probability of having high-quality jobs.

Our findings reveal intriguing insights into the impact of COVID-19 on women. The results from both indexes demonstrate distinct effects, which could be attributed to the ‘she-cession’ effects of COVID-19 and the potential for remote work in the case of women.

Concerning Venezuelan immigrants, all estimates show that being an immigrant decreases the probability of having a good job. Results are in the way of Mora et al. (2022), who have “greater overeducation for Venezuelans who arrived in Colombia in the first wave of migration compared with Colombians and Venezuelans who arrived in Colombia in the recent wave of migration” (p. 515).

Finally, public policies should be implemented to improve the quality of employment. In these, it is crucial to consider that education and gender are fundamental to counteract the effects of a pandemic or any other shock similar to the one experienced with COVID-19.

Data Availability

Data available on request from the authors.

Notes

In Colombia, the first case of COVID-19 was reported on March 6, and most countries had the main effects that month. For example, in Spain, although the first reported case was on January 31, 2020 (Pulido 2021), the main effects occurred during March (see Malo 2021). For example, in Spain, although the first reported case was on January 31, 2020 (Gaceta Medica 2021), the main effects occurred during the month of March (see Malo 2021).

Changes in marital status (married) will be used as an instrument of T*COVID-19. We do not include young people because they are part of the cohort dummies used as instruments.

Using the dummy variable of the time does not eliminate unobservable individual heterogeneity. Only some correlation between this and the random error term can be incorporated. However, other interactions will always exist that cannot be controlled by including variables of this type.

The education variable was instrumented with the cohorts and sectors of occupation.

The variables COVID-19, T, and Men as dummies are free of measurement error (Deaton 1985, pp. 116 and pp. 120). However, in the case of the interaction variable, COVID-19*T, it is not clear that it is free of measurement error, so it was instrumented with cohort dummies interacting with married marital status.

References

Alfaro, L., M. Eslava, and O. Becerra-Camargo, 2022. La exposición del empleo al Covid-19 en Colombia. En Cortés, D., Posso, C. y Villamizar-Villegas, M. (Eds.) Covid-19 consecuencias y desafíos en la economía colombiana. Una mirada desde las universidades, (p. 131–149), Editorial Universidad del Rosario.

Arranz, J.M., C. García-Serrano, and V. Hernanz. 2016. Índice de Calidad del Empleo. Madrid: ASEMPLEO.

Arranz, J.M., C. García-Serrano, and V. Hernanz. 2018. Calidad del empleo: una propuesta de índice y su medición para el periodo 2005–2013. Hacienda Pública Española / Review of Public Economics 225 (2): 133–164.

Arranz, J.M., C. García-Serrano, and V. Hernanz. 2019. Job quality differences among younger and older workers in Europe: the role of institutions. Social Science Research. 84: 102345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.102345.

Arroyo, J., L. Pinzón, J. Mora, D. Gómez, and A. Cendales. 2016. Afrocolombianos, discriminación y segregación espacial de la calidad del empleo para Cali. Cuadernos De Economía 35 (69): 753–783. https://doi.org/10.15446/cuad.econ.v35n69.54347.

Bassanini, A., G. Bovini, E. Caroli, Casanova, J. Fernando, F. Cingano, P. Falco, F. Felgueroso, M. Jansen, P.S. Martins, A. Melo, M. Oberfichtner, and M. Popp. 2023. Labour market concentration, wages and job security in Europe. Working Paper Series No. 654. Nova School of Business Economics.

Becerra, O., M. Cabra, N. Romero, and C. Pecha. 2021. Mercado laboral en la crisis del COVID-19 Resumen de políticas según la iniciativa Respuestas Efectivas contra el COVID-19. DNP. https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Sinergia/Documentos/Notas_politica_publica_EMPLEO_09_04_21_v4.pdf

Bustamante, C.D., and J.S. Arroyo. 2008. La raza como un determinante del acceso a un empleo de calidad: un estudio para Cali. Ensayos Sobre Política Económica 26 (57): 130–175.

Camacho, C.X., L.F. Dussán, and J.C. Guataqui, 2012. Calidad del empleo en Bogotá: una aproximación desde el enfoque de trabajo decente. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Económico, 16.

Camussi, S., V. Maccarrone, and L. Aimone, 2021. Changes in the Employment Structure and in Job Quality in Italy: A National and Regional Analysis. Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Paper), No. 603, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3828111

Cascales, M. 2021. New Model for Measuring Job Quality: Developing an European Intrinsic Job Quality Index (EIJQI). Social Indicators Research 155: 625–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02615-9.

Cassar, L., and ETH-Zurich. 2010. Quality of employment and job satisfaction: evidence from Chile (Publisher's version). Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI).

Castillo, A., and A.P. Acosta. 2018. Calidad del empleo y migración interna en Colombia en 2015. Ciencias Económicas 36 (1): 77–120.

DANE, 2022. Clasificación Única de Ocupaciones CUOC en https://www.dane.gov.co/files/sen/nomenclatura/cuoc/documento-clasificacion-unica-ocupaciones-colombia-CUOC.pdf

Deaton, A. 1985. Panel data from time series of cross-sections. Journal of Econometrics 30 (1–2): 109–126.

Dueñas, D., C. Iglesias, and R. Llorente. 2009. La calidad del empleo en un contexto regional, con especial referencia a la comunidad de Madrid (No. 5, Documentos de trabajo). Recuperado de https://ebuah.uah.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/10017/6543/calidad_duenas_IAESDT_2009.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Eisenberg-Guyot, J., T. Peckham, S. Andrea, V. Oddo, N. Seixas, and A. Hajat. 2020. Life-course trajectories of employment quality and health in the U.S.: A multichannel sequence analysis. Social Science & Medicine 264: 113327.

Ermida-Uriarte, O. 2001. Trabajo Decente y formación profesional. Boletín Cinterfor, No. 151, pp. 9–26. http://www.oitcinterfor.org/sites/default/files/file_articulo/erm.pdf.

Farné, S. 2003. Estudio sobre la calidad del empleo en Colombia. Estudios de economía laboral en Países Andinos No. 5. Lima: OIT.

Farné, S., and C.A. Vergara. 2007. Calidad del empleo: ¿qué tan satisfechos están los colombianos con su trabajo? Coyuntura Social Fedesarrollo 36: 51–70.

Farné, S., and C.A. Vergara. 2015. Crecimiento económico, flexibilización laboral y calidad del empleo en Colombia de 2002 a 2011. Revista Internacional Del Trabajo 134: 275–293.

Farné, S and C. Sanín, 2021. Impacto de la COVID-19 sobre el mercado de trabajo colombiano y recomendaciones para la reactivación económica, Colombia: OIT / Oficina de la OIT para los Países Andinos, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---ro-lima/---sro-lima/documents/publication/wcms_775897.pdf

Galvis, L.A., G. Rodríguez, and S. Ovallos. 2021. Calidad de vida laboral en Cartagena, Barranquilla y Santa Marta. Cuadernos De Economía 40 (82): 307–338. https://doi.org/10.15446/cuad.econ.v40n82.81233.

García-Serrano, C., J.M. Arranz and Hernanz, V. 2017. Job quality: Are there differences by types of contract? Social Indicators Research, http://https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1586-4.

Gómez, M.S., L.A. Galvis, and V. Royuela. 2017. Quality of work life in Colombia: A multidimensional fuzzy indicator. Social Indicators Research 130 (3): 911–936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1226-9.

International Labour Organization [ILO]. 2012. Decent work indicators: Guidelines for producers and users of statistical and legal framework indicators (1st ed.). https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---integration/documents/publication/wcms_229374.pdf

Isaza-Castro, J. 2021 El impacto de la COVID-19 en las mujeres trabajadoras de Colombia. Colombia: OIT / Oficina de la OIT para los Países Andinos. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/es/publications/el-impacto-de-la-covid-19-en-las-mujeres-trabajadoras-de-colombia

Jiménez, D.M.J., and J.N.P. Páez. 2014. An alternative method for measuring employment quality in Colombia (2008–2012). Sociedad y Economía 27: 129–154.

Lasso, F.J., and C.C. Frasser. 2015. Calidad del empleo y bienestar: Un análisis con escalas de equivalencia. Ensayos Sobre Política Económica 33 (77): 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.espe.2014.11.00.

Lažetić, P. 2020. The gender gap in graduate job quality in Europe: A comparative analysis across economic sectors and countries. Oxford Review of Education 46: 129–151.

Malo, M. 2021. El empleo en España durante la pandemia de la COVID-19. Panorama Social 33: 55–73.

Ministerio de Salud de Colombia 2020, Medidas para afrontar la covid-19 tras un mes de su llegada al país. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Paginas/Medidas-para-afrontar-la-covid-19-tras-un-mes-de-su-llegada-al-pais.aspx

Moffitt, R. 1993. Identification and estimation of dynamic models with a time series of repeated cross-sections. Journal of Econometrics 59: 99–123.

Mora, J.J., and J. Muro. 2008. Sheepskin Effects by Cohorts in Colombia. International Journal of Manpower 29 (2): 111–121.

Mora, J.J., and M.P. Ulloa. 2011. Calidad del empleo en las principales ciudades Colombianas y endogeneidad de la educación. Revista De Economía Institucional 13 (25): 163–177.

Mora, J.J., L. Pérez, and C. González. 2016. La calidad del empleo en la población Afro-Colombiana utilizando índices sintéticos. Revista De Métodos Cuantitativos Para La Economía y La Empresa 21: 117–140.

Mora, J.J., D. Herrera, and J.F. Álvarez. 2021. Pandemia y duración del desempleo juvenil en Cali. Revista De Economía Institucional 24 (46): 195–216.

Mora, J.J., M. Castillo Caicedo, and G.A. Gómez. 2022. Migration and Overeducation of Venezuelans in the Colombian Labor Market. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 65: 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-022-00371-z.

Mora, J.J., A. Cuadros-Menaca, and J.T. Sayago. 2023. South-South migration: The impact of the Venezuelan diaspora on Colombian natives’ wages and hours worked. Applied Economics Letters 30: 884–891.

Pulido, S (2021). Un año buscando el tratamiento contra la COVID-19, Gaceta Medica in https://gacetamedica.com/investigacion/un-ano-buscando-el-tratamiento-contra-la-covid-19/. Accessed 10 Nov 2023.

Reinecke, G. and M.E. Valenzuela. 2000. La calidad del empleo: un enfoque de género. En M. Valezuela y G. Reinecke (Eds.). ¿Más y mejores empleos para las mujeres? La experiencia de los países del Mercosur y Chile, (pp. 29–58), Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT).

Royuela, V., and J. Suriñach. 2013. Quality of work and aggregate productivity. Social Indicators Research 113: 37–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0081-1.

Sehnbruch, K., P. González, M. Apablaza, R. Méndez, and V. Arriagada. 2020. The Quality of Employment (QoE) in nine Latin American countries: a multidimensional perspective. World Development 127: 1–20.

Slaughter, J. (1993). Should We All Compete Against Each Other? Labor notes, 170, mayo, pp. 7–10

Somarriba, N., M.C. Merino, G. Ramos, and A. Negro. 2010. La calidad del trabajo en la Unión Europea. Estudios De Economía Aplicada 28 (3): 1–22.

Storer, A., D. Schneider, and K. Harknett. 2020. What explains racial/ethnic inequality in job quality in the service sector? American Sociological Review 85 (4): 537–572.

Thoreau, M. (2022). Ohioline Fact Sheet, The She-cession: How the Pandemic Forced Women from the Workplace and How Employers Can Respond. in https://u.osu.edu/mindstretched/2022/02/02/ohioline-factsheet-%20the-she-cession-how-the-pandemic-forced-women-from-the-workplace-and-how-employers-can-respond/. Accessed 2 Oct 2024.

Van Bastelaer A.-Hussmann R.(2000). Measurement of the quality of employment: introduction and overview. documento presentado al Joint ECE-Eurostat-Ilo Seminar on Measurement of the Quality of Employment, Geneva, may

Weller, J. and C. Roethlisberger, 2011. La calidad del empleo en América Latina. Macroeconomía del Desarrollo, No. 110. CEPAL. http://hdl.handle.net/11362/5341

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Colombia Consortium. The authors are thankful to the grant of the Fundación Carolina for Postdoctoral Research (2002) and Internal Grant Agency of Universidad Icesi for the Project No.: COL0014387 for financial support to carry out this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

We declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mora, J.J., Arranz, J.M. The Effect of COVID-19 on the Quality of Employment in Colombia. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 67, 1141–1157 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-024-00530-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-024-00530-4