Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching consequences worldwide and has also led to significant changes in people’s lifestyles, resulting in an increase in social problems, such as early marriages for girls in different contexts. This study aimed to examine the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and early marriage among girls. Our analysis of 36 studies published between 2020 and 2023 shows that the pandemic has accelerated the number of early marriages for girls in several ways. In many countries, early marriages often result from social disintegration, loss of social support, inability to pay for basic needs, prolonged school closures, economic collapse, and parental death due to COVID-19. Although people in different contexts have different opinions about early marriages for girls due to COVID-19, there is evidence that early marriages for girls are sometimes seen as a solution to ease the financial burden and reduce stress for parents. However, there was a significant decline in traditional marriages in developed countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the United States, Mexico, Japan, Korea, and Indonesia. Early marriage can have serious consequences for young adolescents, including mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and feelings of powerlessness. Mixed results, such as an increase or decrease in early marriage among girls, indicate a need for detailed contextual empirical research. It is known that actions are being taken to reduce the prevalence of early marriages, especially in developing countries, but certain situations may accelerate or reverse trends in girls’ early marriages because of various social, economic, and cultural influences. This study suggests further consideration of strategic planning for emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, that people may face again in the future. Therefore, it is necessary to implement appropriate support for abused and mistreated girls by raising awareness to reduce the psychological and physiological consequences of early marriage due to the pandemic in the near past.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background and introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a devastating global catastrophe in recent years (Ahmed et al., 2023). This global crisis has had far-reaching consequences for people’s lives in a variety of areas. According to UNESCO (2020), the pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on children, particularly those living in low-income countries. Due to significant job losses and economic insecurity, the pandemic has increased concerns regarding child labor, early marriage, and child trafficking (Gupta and Jawanda, 2020).

Global attempts to end the early marriage of girls are at risk owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nigeria, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Brazil, and India are the five nations in which the pandemic has had a particularly negative effect on early marriages. If action is not taken to address the issue, estimates indicate that the number of child brides in these nations might climb by 3.5 million over the course of the next ten years (Yukich et al., 2021). Furthermore, studies conducted in several countries have shown an increase in the number of adolescent marriages (Jones et al., 2020; Pathak and Frayer 2020). According to UNICEF’s projections, COVID-19 will put an extra 10 million girls at risk of being married as children (UNICEF, 2021a). According to Save the Children, by 2025, COVID-19 may increase the number of girls at risk of child marriage by 2.5 million (Cousins, 2020). Furthermore, the organization assumed that 500,000 more girls, including 200,000 from South Asia, have been married against their will in 2020, with an extra one million child brides facing the risk of pregnancy as a result (Save the Children, 2020). The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNDP, 2015) call for all governments to work together to eliminate human rights breaches and promote global equality by 2030.

According to UNICEF (2023), “child marriage” or “early marriage” is the act of getting married to or starting an “informal union”Footnote 1 with a girl or boy who is younger than 18. This practice, commonly defined as marriage before the age of 18, is against the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) because it takes place before the girl reaches the age at which she is expected to be physically, biologically, and psychologically mature enough to take on the responsibilities of marriage and motherhood.

Early or child marriage is a common occurrence in many nations and is frequently excused by cultural customs that violate the rights of women and girls. As children cannot provide informed permission, it might be considered a type of forced marriage. Within a community, sociological, cultural, and political conditions affect the occurrence of child marriages. The annual rate of child marriages varies by nation and time period, and both industrialized and developing countries face this problem. However, even within a country, the proportion may vary based on the demographic, social, and political situations of various communities (UNICEF, 2005). UNICEF (2021b) identified five channels through which the pandemic has accelerated the rate of child marriage: school closures, economic insecurity, healthcare service disruptions, orphanhood due to parental death, and disruptions in programs and services targeting the eradication of child marriage.

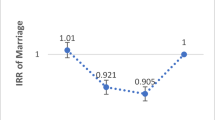

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a notable increase in the incidence of early marriages in a number of nations worldwide. It is well acknowledged that South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have the highest rates of early marriages. Nonetheless, it should be mentioned that people who follow traditional lifestyles frequently marry during or shortly after puberty in places such as the Middle East, North Africa, and some parts of Asia. Furthermore, prepubescent marriages are common in many parts of South Asia, West Africa, and East Africa. In some parts of Eastern Europe and some parts of Latin America, it is common for girls under the age of eighteen to marry (UNICEF, 2001). Conversely, it is crucial to understand that not all countries have experienced an equal rise in the number of early marriages; therefore, this trend has not been widespread. The number of weddings during the pandemic has decreased in comparison to pre-pandemic times in a number of nations, including Korea (Kim and Kim, 2021), Japan (Ghaznavi et al., 2022), Indonesia (Nursetiawati et al., 2022), Mexico (Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2023), and the USA (Manning and Payne, 2021).

This study aims to examine how COVID-19 contributes to the early marriage of girls in particular and what factors are involved in the increase or decrease in marriages due to the effects of the pandemic in different regions, including Nigeria and Bangladesh. This study draws on current published studies and illustrates these links. Synthesizing the many results demonstrating the convergence and divergence of COVID-19’s influence on early marriage from research conducted in different contexts would guide policymakers and help them prevent an increase in early marriages should a similar pandemic arise in the future. The results of this study will help to understand population dynamics, which require a detailed study based on a large dataset of population surveys and COVID-19 infections. The main findings of this study can help policymakers understand how COVID-19 leads to early marriage and negatively affects girls’ mental health. The study also suggests how to ensure support for young girls during critical periods and increase counseling for their mental well-being.

This paper is organized as follows: the section “Background and introduction” presents the background and introduction, and the section “Methodology” presents the methodology. Section “Nexus of COVID-19 pandemic and early marriage” provides an overview of the global scenario of early marriage and its associated factors. This section also discuss the relationship between early marriage and the COVID-19 pandemic, with two important subsections. The first subsection explores how the COVID-19 pandemic has led to marriages among young people worldwide. The second subsection examines how the pandemic has slowed down young marriages worldwide. Section “Mental health status of early married girls” briefly discusses the impact of early marriage on girls’ mental health during the pandemic period. Next, in the section “Global scenarios of early marriage and associated factors” we briefly summarizes both developed and developing countires experiences of marriage along with their socio-cultural perspectives. Finally, we end with a “Concluding discussion”section where we summarized our findings with other relevant literature. We also acknowledge some limitations of our study and suggest areas for future research.

Methodology

Searching for relevant articles

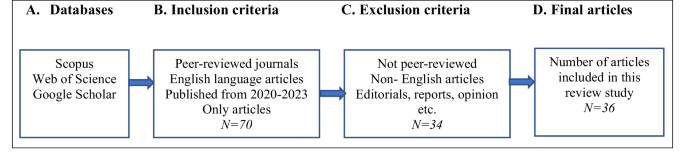

In this research, we sought to investigate the global impact of COVID-19 on early marriages. To this end, we utilized reputable databases, such as Scopus, Google Scholar, and Web of Science, which offer diverse perspectives on contemporary issues (Malinen, 2015) and have been employed in numerous previous studies (Ahmed et al., 2022; Haq et al., 2021; Wan et al., 2021). Our search strategy primarily entailed employing keywords such as “COVID-19 and early marriage”, “marriage during COVID-19”, “child marriage during the pandemic”, and “COVID-19 and child marriage”.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria and final article selection

The participating authors independently searched for relevant articles in the databases, using specific keywords. The search was performed in online libraries, and 70 articles that focused on the link between COVID-19 and early marriage in any country were identified as potentially relevant to the study. These articles were downloaded and reviewed for abstracts and full text, with strict adherence to the inclusion criteria of this study. In both the abstract and full text, we examined two main aspects: (a) the impact of COVID-19 on the prevalence of early or child marriage, and (b) the characteristics or variables associated with COVID-19 that influence the occurrence of early or child marriage. Initially, we sought solutions to these inquiries in the abstract. If we discovered they were not present, we examined the full text. Only peer-reviewed English articles published between 2020 and early 2023 were considered, and those that found no link between COVID-19 and early marriage were excluded. Moreover, editorials, letters, meeting reports, and non-English studies were excluded to avoid complications and confusion related to translations. Following the selection process, 36 peer-reviewed articles in academic journals were included in the literature review. The article selection process used in this study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Nexus of COVID-19 pandemic and early marriage

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the widespread closure of schools, which has significantly contributed to an increase in child marriages during this period. Research conducted by Jones et al. (2020) shows that girls who do not attend school are more likely to accept marriage proposals from their guardians, whereas those who attend school are more likely to resist such arrangements with the support of their peers and educators. This finding is corroborated by the findings of the BRAC (2020).

Another concern is the growing fear among the population due to rising incidents of rape and other forms of violence against women (Sifat, 2020). With schools closed, young men in the area may resort to verbal harassment or even violent assault to pass the time. As a result, many families opt to marry their daughters to keep them safe, rather than seek justice for sexual assault. The research conducted by Paul and Mondal (2020) supports this observation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a decrease in the monitoring of child marriages as local government personnel are preoccupied with related matters. Mahato (2016) identifies several factors contributing to child marriage in Nepalese society, such as a lack of education, inadequate access to information, and a fear of remaining unmarried. Similarly, Khanom and Islam Laskar (2015) linked factors such as low parental education, social norms, and adolescent cell phone and Internet use to the increase in child marriage in the Assam Province of India.

Existing literature suggests that financial hardship during the COVID-19 pandemic can both hasten and delay marriages. When a family struggles to meet their basic needs, girls may marry to alleviate financial pressure (Bahl et al., 2021; Chowdhury, 2021; Deane, 2021; Rahiem, 2021; Baird et al., 2022). Conversely, economic pressure caused by financial difficulties may delay marriages (Banati et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021). Furthermore, the death of parents due to the virus has led some couples to marry for the sake of their children’s safety and security, with the spouse assuming a guardian role for orphans (Deane, 2021).

According to Esho et al. (2022), the COVID-19 pandemic has had the effect of accelerated marriages owing to a variety of factors. The financial conditions of many families were disrupted by the pandemic, which increased the likelihood of early forced marriage of girls to reduce family burden (Bahl et al., 2021; Chowdhury, 2021; Rahiem, 2021; Deane, 2021; Baird et al., 2022; Banati et al., 2020). As COVID-19 generated financial problems, families were eager to marry off their sons for dowry (Musa et al., 2021). The same factor also decelerated the marriages of males, as their marriage would increase family burden (Banati et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021). Deane (2021), Amin et al. (2020), Musa et al. (2021), Carter et al. (2022), and Esho et al. (2022) found that long-term school closures are contributing factors to early marriage. Additionally, the deaths of parents during the pandemic have caused children to marry early to ensure their security (Deane, 2021). Raheim (2021) and McNulty et al. (2023) explored marriage as a strategy for escaping from boredom, stress, studying, household tasks, and loneliness and found that young people were willing to marry during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, intimate couples tended to marry quickly to maintain their relationships during unstable times (Komura and Ogawa, 2022). Furthermore, a lack of social support and these laws have contributed to an increase in the marriage rate during the pandemic (Jones et al., 2020; Rahiem, 2021; Banati et al., 2020; Esho et al., 2022; Deane, 2021; Bahl et al., 2021; Musa et al., 2021). Factors that decrease the marriage rate include limitations on wedding services (Wagner et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021; Nursetiawati et al., 2022), restrictions on public gatherings (Kim and Kim, 2021), closure of wedding venues (Wagner et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021; Komura and Ogawa, 2022), and economic breakdown of families (Kim and Kim, 2021; Banati et al., 2020).

The following sections describe how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected early marriages worldwide.

COVID-19 accelerated the marriages of young

The ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in the number of cases of early marriage, as per the research conducted by Esho et al. (2022). The crisis has exacerbated various social and economic factors that influence early marriage and has opened new avenues for children and early marriages, as per Deane (2021). Rahiem (2021) highlighted that financial concerns are a significant reason behind early marriage during the pandemic, as guardians marry off their children at younger ages because of the belief that marriage provides an escape from the boredom and stress of being at home during the pandemic. Additionally, traditional laws, peer pressure, and a lack of knowledge about the consequences of early marriage are other factors that have contributed to the rise in early marriage during the pandemic.

Candel and Jitaru (2021) state that the pandemic has affected the desire to enter into a marital relationship, with concerns about COVID-19 impacting the stigma associated with being single and increasing the awareness of the importance of stability and familial ties. For example, prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a prevailing belief among many individuals that being unmarried did not necessarily indicate a state of unhappiness. It is not a matter that necessitates resolution. It is indeed an exceptional opportunity to bring joy to someone’s life. On the contrary, being married entails prioritizing the well-being of others over one’s happiness. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous individuals modified their beliefs as they recognized that unmarried individuals were considered lacking, isolated, and unhappy, while marriage was granted more fulfillment and social status. More importantly, deep interpersonal relationships during the early stages of the pandemic provided a framework for self-affirmation and emotional elevation. Couples who perceived their lives to be in danger due to the pandemic understood the value of the family and the sharing of risks, which influenced their decision to marry during the crisis, as per Komura and Ogawa (2022).

Before the COVID outbreak, teenagers spent an excessive amount of time with friends. However, during the pandemic, adolescents communicated and engaged only online. Some teenagers decided to marry during the pandemic due to loneliness, as per Rahiem (2021).

Adolescents have historically resorted to marriage as a means of escaping household chores and academic responsibilities, a phenomenon observed by Rahiem (2021). McNulty et al. (2023) further highlighted that acute stressors have been found to be correlated with a higher likelihood of marriage and increased satisfaction. This may be attributed to the fact that stress can prompt individuals to rely on their natural behaviors, which may be advantageous for achieving a state of happiness and well-being.

The following sections discuss how COVID-19 promotes early marriage in numerous ways.

Interruptions to schooling

Paul and Mondal (2020) cautioned that the probability of child marriage, mistreatment, sexual assault, and domestic violence would rise if educational institutions, such as elementary schools and high schools, were forced to shut down during this unfortunate situation. The ongoing closure of schools continues to have a detrimental effect, as noted by Amin et al. (2020). COVID-19-related school closures have affected the education of over 1.6 billion children globally, as reported by Musa et al. (2021). Moreover, school closures in the Democratic Republic of Congo have increased the risk of early marriage for females, as seen in studies by Deane (2021), Carter et al. (2022), and Esho et al. (2022).

Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, the teaching and learning process has undergone significant changes that have proven challenging to implement remotely. Consequently, parents are increasingly expected to explain the learning process to their children, with many doing so in a frustrating manner. In particular, high school seniors may choose to tie the knot because of their frustration with online classes, unwavering trust in their partners, and overall dissatisfaction with their lives (Rahiem, 2021). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted school systems and exacerbated educational inequality by reducing Opportunities and resources for disadvantaged children, thereby increasing the likelihood of early marriages (Deane, 2021). UNICEF estimates that the probability of marriage due to school closures and dropouts is 27.5% annually, increasing by 25% each time a school is closed (Musa et al., 2021).

Some young people marry to avoid taking online courses as they lack the necessary technology or face other barriers to accessing online education (Rahiem, 2021). Parents may also lack the financial resources to support their daughters’ schooling because of the economic loss caused by the pandemic (Chowdhury, 2021). Teachers often cite teenage girls’ marriages as the primary reason for their absence during school closures (Carter et al., 2022). In a study by Amin et al. (2020), one in ten girls indicated that they might not return to school after it reopened because of factors such as learning gaps, financial difficulties at home, and marriage. The most frequently cited factor by Ethiopians, who believed that the number of child-forced marriage cases was rising during the pandemic, was individuals spending more time at home, including potential victims of child-forced marriage (80%) (Esho et al., 2022).

Financial difficulties

The financial impact of COVID-19 on families (Deane, 2021; Rahiem, 2021) has led to the perception that marriage could alleviate financial difficulties (Bahl et al., 2021; Chowdhury, 2021; Rahiem, 2021). Many families face financial hardship, making it difficult for parents to afford to send their children to school (Rahiem, 2021). Economic challenges in impoverished families pose a risk and play a significant role in marrying young girls to ease the financial burden on the family and provide a better future for their offspring (Mehra et al., 2018). Additionally, financial hardships resulting from COVID-19 led many girls to marry young people, and many parents believed that education was a waste of money. Parents and girls believed that marriage would improve economic prospects and the overall quality of life. The economic consequences of COVID-19, including reduced income, job loss, and travel restrictions, have contributed to household poverty and increased economic insecurity, which may hinder parents’ ability to meet their children’s needs (Deane, 2021). Many teenagers reported that their families experienced negative economic shocks due to COVID-19, such as the inability to afford necessities or job loss (Baird et al., 2022). These changes have resulted in decreased well-being outcomes in mental health, hunger, and financial management (Baird et al., 2022). The pandemic has exacerbated the difficulties faced by girls, making the situation more challenging (Musa et al., 2021). For instance, the financial crisis caused by COVID-19 has led to an increase in weddings among Syrian women (Banati et al., 2020).

The demise of a parent

One contributing factor to adolescent females getting married during the pandemic is the death of a parent. Mangeli et al. (2017) find that young people marry early to settle family issues and contribute to the family’s financial stability after the loss of a parent. McDougal et al. (2018) also noted that adolescent girls who have experienced the loss of a parent are more likely to marry at a young age in search of a loving and supportive partner. Additionally, some local customs and beliefs encourage couples to marry and start families at a young age after the death of their parents (Rahiem, 2021). A study by Deane (2021) found that the likelihood of a female orphan dropping out of school to care for younger siblings or being married increases after losing both parents, as close relatives may find it difficult to support them. This increases the likelihood of female orphans marrying at a younger age. Furthermore, orphaned females were more likely to be married than orphaned males.

Malfunctions in awareness programs

Parents reportedly exert pressure on their daughters to marry even in the early stages of adolescence. This trend can be attributed, in part, to the fact that there are fewer local government officials and teachers around, as many have returned to their hometowns (Banati et al., 2020). Additionally, the lack of safe spaces and protection for girls, which are typically provided by institutions and rescue centers, may contribute to the rise in child-forced marriages (Esho et al., 2022). The scarcity of local government representatives is another significant factor that increases the likelihood of child marriages (Jones et al., 2020). Adolescent males and girls in Ethiopia stated that they felt more pressure to marry because of the absence of educational institutions, particularly during the regular marriage season in three of the six towns where the study was conducted (Banati et al., 2020). Consequently, during the pandemic, monitoring potential child marriages was hindered, and adolescent girls lost their important roles in educational institutions for sharing information against forced marriages.

Anti-child marriage campaigns in India were halted during the lockdown period. Research indicates that a one-year delay in anti-child marriage campaigns globally might result in 13 million additional child marriages worldwide between 2020 and 2030 due to the economic slump and other factors (Bahl et al., 2021). The pandemic created two additional reasons for child marriage. Girls and women may find it challenging to access programs and services designed to prevent child marriages because of pandemic-related transportation restrictions and social exclusion (Deane, 2021). In Nigeria and other parts of the world, the pandemic has also impacted organizations’ efforts to prevent the practice of early marriage. The COVID-19 outbreak interferes with the efforts of numerous groups working at the local level to end child marriage while exacerbating many of the complex issues that cause it (Musa et al., 2021). Local people believe that attaining puberty enables one to enter a marriage relationship legally. Parents with limited education are often in the dark regarding the long-term effects of child marriage (Rahiem, 2021).

COVID-19 reduces the marriage rates

A decline in marriage rates during the COVID-19 pandemic has been observed in Korea, Japan, Indonesia, Mexico, and the USA (Wagner et al., 2020; Manning and Payne, 2021; Kim and Kim, 2021; Ghaznavi et al., 2022; Nursetiawati et al., 2022; Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2023). Restrictions on wedding services were put in place with the aim of reducing the crowd size and subsequently limiting the transmission of COVID-19 (Wagner et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021; Nursetiawati et al., 2022). The pandemic has disrupted wedding plans by closing venues, restricting public transportation, and employing other measures. Social isolation and lockdown measures, although varying in scope, have also contributed to delays in wedding plans (Kim and Kim, 2021; Wagner et al., 2020). Some weddings have been postponed until the pandemic is over, whereas others may never take place because of concerns about exposing guests to health risks (Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2023). Business closures have forced many couples to postpone their marriages, with only essential services exempt. The filing of marriage certificates may also be delayed if the ceremony is postponed or cancelled, as this document is typically submitted prior to the wedding (Komura and Ogawa, 2022).

Due to concerns surrounding the coronavirus, engaged couples may choose to cancel or postpone their weddings (Kim and Kim, 2021). For instance, between 2019 and 2020, there was a notable decrease in marriages in the United States (Wagner et al., 2020; Candel and Jitaru, 2021; Manning and Payne, 2021). According to media accounts, the pandemic has led to a decline in marriages in Japan (Ghaznavi et al., 2022). The increase in COVID-19 infections caused a 9.6–13.9% decrease in the crude marriage rate in South Korea. In addition, the marriage rate was further reduced in Korea’s provinces with higher infection rates (Kim and Kim, 2021). The number of weddings during the pandemic suggests that there was at least a 20% decline in weddings in the Florida, Missouri, and Oregon states of the USA (Manning and Payne, 2021). Indonesia postponed marriage ceremonies during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (Nursetiawati et al., 2022). Similarly, marriage rates in Mexico decreased by over 90% in April and May 2020 (Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2023). Following the declaration of the emergency in April 2020 and the subsequent request for people to stay home, there was a 10% decline in marriages in Japan (Komura and Ogawa, 2022).

Due to economic difficulties such as financial instability caused by job disruption, young couples are increasingly delaying marriage. Studies have shown that a lack of secure employment is the primary reason for postponing marriage (Kim and Kim, 2021). Economic crises can also affect marriage rates, as young girls in Lebanon believed that an economic crisis would lead to a decline in their marriage rates. Palestinian and Lebanese boys also reported that economic conditions make it challenging for them to consider marriage and maintain expectations for the future (Banati et al., 2020).

Mental health status of early married girls

It is widely recognized that teenage girls are disproportionately affected by the long-term negative consequences of the public health crisis. The difficulties faced during adolescence may contribute to mental health issues, sexual and reproductive health problems, and chronic illnesses later in life (Bosquet et al., 2018; Felitti et al., 1998; Herrenkohl and Jung, 2016; Chari et al., 2017; Lang et al., 2010). Additionally, married teenagers often feel resentful towards their peers, who have the luxury of spending their days playing. Simultaneously, teenagers are responsible for taking care of their homes and younger siblings, which can exacerbate feelings of depression if not properly managed. Furthermore, teenagers may experience increased anxiety disorders because of their partners’ abusive behavior. Physical violence, such as that experienced in the case of early marriage, can result in mental health issues such as anxiety, low self-esteem, feelings of helplessness, post-traumatic depression, and unhealthy dependence on husbands, some of whom may have abused them.

Physical violence, such as that experienced in the case of early marriage, can result in mental health issues such as anxiety, low self-esteem, feelings of helplessness, post-traumatic depression, and unhealthy dependence on husbands, some of whom may have abused them. The mental health of adolescent girls can be negatively affected by emergency public health measures such as home isolation, social restrictions, and school closures (Shukla et al., 2023). School closures or restrictions on extracurricular activities can have significant impacts on children’s daily lives and mental well-being (Ghosh et al., 2020; Saha et al., 2023). During the pandemic, Indonesian teenagers struggle with academic pressure and parental expectations, and many need more mental and emotional support (Rahiem, 2021).

Global scenarios of early marriage and associated factors

Early marriage is a widespread issue that extends beyond official statistics, as it often excludes unauthorized marriages in certain regions and among specific populations (UNICEF, 2001). Cultural diversity leads to significant variations in the prevalence of early marriage across different parts of the world. Economic and political conditions have a significant impact on the prevalence of early marriage, which varies greatly between nations. In some Asian countries, marriage is viewed as a religious obligation or societal responsibility, whereas in Western countries, remaining unmarried is widely accepted (Himawan, 2019).

Scenario of developed countries

Societal beliefs and perceptions of marriage, including appropriate age and selection methods, shape cultural norms and practices surrounding the institution. These beliefs include the family’s purpose, organization, lifestyle, and responsibilities of its members. The historical evolution of marriage is evident, as the concept and purpose of the family vary significantly across different societies and periods (UNICEF, 2001). Historically, marriages in Western Europe have been viewed as financial transactions, with limited emphasis on the individuals involved. Women are often considered property transferred from their fathers to their husbands (UNICEF, 2001). However, this perspective has undergone significant change in recent years. The contemporary concept of marriage, commonly referred to as the “romantic” notion, has emerged as the predominant ideal characterized by principles such as mutual consent, passionate affection, and personal fulfillment. While most nations have legal frameworks governing marriage with criteria such as mandatory age and willingness, enforcement of these laws may be lacking.

In developed countries such as Europe, Oceania, and North America, the incidence of early marriage among women is relatively low, with only a small proportion entering matrimony before the age of 18 years. For instance, in the United States, only 4% of women marry before the age of 18, while in Germany, the figure is even lower, at 1% (World Marriage Patterns, 2000). It is important to acknowledge that the practice of early marriage is not limited to underdeveloped countries as it is also prevalent in affluent societies. In fact, even Western countries, such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, are experiencing an increase in the occurrence of child marriages within immigrant communities residing within their territories. Customary practices persist even after relocation, and acceptance of child marriage can persist despite the cultural contexts of the adopted nation (Tahirih Justice Center, 2018). Adolescent girls from immigrant families who adhere to the tradition of child marriage may be repatriated to their families’ countries of origin with the intention of being married or traded as spouses to older individuals (Jeffreys, 2009).

This section explores the historical and cultural dimensions of Turkey, along with the correlation between COVID-19 and early marriages, in order to gain an understanding of the country’s culture, legislation, and response to the pandemic.

Turkey

The minimum age for marriage in Turkey is 18, as stipulated in Article 124 of the Turkish Civil Code (TCC) (TCC, art. 124). Nevertheless, according to the TCC, individuals who are 17 years old are allowed to get married as long as they have the consent of their parents. Furthermore, individuals who are 16 years old can obtain judicial approval to marry, but only in unusual circumstances and for compelling reasons (TCC, art. 124). Nevertheless, the TCC does not provide any clarification regarding the specific details of those extraordinary circumstances. In Turkey, where marriage is prevalent, there has been a slight rise in the age at which people first get married and a decrease in marriages involving individuals under the age of 18 over the years.

Conversely, there was a decline in the percentage of women endorsing any form of physical violence. At the same time, there was an increase in the percentage of women asserting their right to reject sexual interaction. During the COVID-19 crisis, there has been an increase in child weddings in Turkey, particularly with Syrian refugees who are marrying their underage daughters to Turkish males (Global Citizen Report supra note 21, 2020). The phenomenon of Syrian families engaging in the sale of their daughters to Turkish males has experienced a surge in prevalence. This practice serves as an economic survival strategy for Syrian families who lack alternative sources of income or means to support their children (Turkey ECPAT Report, supra note 25). Turkish men rationalize the practice of both polygamy and underage marriage among Syrian refugees as appropriate actions during the times of COVID-19, invoking Muslim religious and cultural narratives and traditions (Musawah Thematic Report on Article 16 and Muslim Family Law, 2016).

Sezgin and Punamäki (2020) highlighted that the early marriage phase and teenage pregnancy pose a threat to women’s physical, mental, and reproductive well-being as well as their economic and social advancement in Turkey. The mental health implications of adolescent pregnancies may be more significant than initially thought. Young-age pregnancy and early marriage are associated with an increased risk of illness and frequent medication use among women (Sezgin and Punamäki, 2020). According to Sezgin and Punamäki (2020), early marriage and adolescent pregnancy can have a serious negative impact on a woman’s reproductive, emotional, and psychological health, as well as economic and social mobility. Teenage pregnancy is a major mental health hazard, but early marriage and adolescent pregnancy also pose risks to the reproductive health of teenagers in Turkey, including cardiovascular diseases. Adolescent pregnancies pose a much greater risk to the mental health of the women involved if they also undergo sexual coercion in their relationships (Sezgin and Punamäki, 2020).

Scenario of developing countries

In several countries across Sub-Saharan Africa, over 40% of young women marry before the age of 18, according to the Alan Guttmacher Institute (1998). In Bangladesh and Afghanistan, more than half of females marry before reaching age 18, as reported by World Marriage Patterns (2000). While a survey by UNICEF (2001) showed a lower incidence of early marriage in the Middle East and North Africa region compared to South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, approximately 11.5% of adolescent females aged 15–19 in the Caribbean and Latin America regions were married.

The relationship between early marriage and educational attainment is complex. In some cases, financial constraints prevent students from continuing their studies, leading parents to opt for early marriage, particularly for their daughters (Bawono et al., 2019). Before entering a relationship or marriage, it is essential to consider one’s financial situation, as couples require a minimum level of financial fulfillment to maintain their relationship (Alola et al., 2020; Hoehn-Velasco et al., 2023). During economic crises, research suggests that male employment is more negatively affected than female employment, as indicated by the negative correlation between unemployment and marriage rates. However, other studies point to the opposite link, where marriage is seen as protection against difficult economic times (González-Val and Marcén, 2018). At such times, women’s families may use their daughters’ marriages to reduce economic burdens, while men’s families may use marriage as a compensating tool by receiving dowries from the bride (Ahmed, 2012).

In some instances, instead of imposing penalties on those who breach the law, the marriage is considered null or void. This often places the woman in an unfavorable position, particularly if she has engaged in sexual intercourse or has offspring. The complexity of the situation is further exacerbated by the presence of countries with multiple legal frameworks, including conventional and religious systems, which operate concurrently but frequently experience conflicts or tensions. In countries such as Afghanistan, the process of birth records is irregular, leading to a lack of accurate information regarding the age at which individuals enter marriage (Women Living Under Muslim Laws (2013)). In nations experiencing persistent civil unrest, there are severe indications of social turmoil related to children, including an increase in the number of children living on roadsides, employment of very young individuals, an increase in child slavery and criminal activity, and elevated levels of child abuse and neglect (Black, 2000). Available evidence suggests an upward trend in young marriages under these circumstances. In Afghanistan, the prevalence of armed conflict and subsequent militarization has contributed to a notable rise in the occurrence of early marriages among adolescent females (Human Rights Watch, 2012). In Sri Lanka, a country plagued by violence, child marriage is primarily motivated by the desire to prevent abduction or forced recruitment into terrorist organizations active in the region (Wijeyesekera, 2011).

Considering the COVID-19 pandemic, research has revealed both the positive and negative effects of economic instability on the occurrence of marriage in developing countries. Chowdhury (2021) posits that financial hardships can expedite the decision to marry, while Kim and Kim (2021) indicate that they can delay the timing of marriage. The pandemic has had a significant impact on the marriage rate among young women, regardless of their geographical region, religion, or cultural background, which is attributed to the restrictions on public gatherings (Komura and Ogawa, 2022).

However, the pandemic has led to an increase in child marriages in developing and underdeveloped areas due to the closure of educational institutions (Deane, 2021) and economic deterioration (Bahl et al., 2021). Parents’ traditional values often result in arranging marriages for their daughters to alleviate financial strain and reduce the family burden during confinement. According to the Manusher Jonno Foundation (2020), poverty caused by the epidemic is the primary cause of the recent increase in the prevalence of child marriage. BRAC (2020) found that 71% of COVID-19-related child weddings occur due to school closures in developing countries. Previous studies have shown that child marriage is more likely to occur after natural catastrophes and public health situations (Paul and Mondal, 2020). For example, the Ebola epidemic in West Africa (2014–2016) was associated with a significant increase in child labor, early marriages, teen pregnancies, and illicit sexual activity. The high school dropout rate in Sierra Leone contributed to a rise in teen pregnancies and marriages (Girls not Brides, 2020).

Child marriage is a prevalent issue among females in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, with the latter exhibiting direst circumstances. Projections indicate that the prevalence of child marriages among women in the region will double by 2050, resulting in sub-Saharan Africa surpassing South Asia as the area with the highest number of young brides. It is anticipated that Nigeria will have the highest prevalence of child marriages among African countries (UNICEF, 2014). In five nations—Nigeria, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Brazil, and India—the pandemic has had a devastating effect on the practice of early marriage. According to estimates, there may be an additional 3.5 million child brides in these nations in the next decade unless something is done to stop the practice (Yukich et al., 2021). Considering the historical and cultural context of the country, it is crucial to gain a comprehensive understanding of the child marriage situation.

In this section, we examine the historical and cultural aspects of Nigeria and Bangladesh, as well as the connection between COVID-19 and early marriages, to comprehensively understand the country’s culture, laws, and COVID-19 response.

Nigeria

After nearly 15 years of military governance marked by corruption, inadequate infrastructure, and unequal distribution of resources, Nigeria transitioned to civilian rule in 1999 with the implementation of a new constitution (Population Council, 2004). Despite possessing vast human and natural resources, Nigeria continues to face significant economic challenges, making it one of the world’s poorest nations (Population Research Bureau, 2003). The AIDS epidemic has had a profound impact on Nigeria, resulting in many affected individuals.

Marriage in Nigeria is governed by three legal systems: Islamic (following the Maliki School of Law), civil (governed by statutory law), and customary (based on traditional law). In the northern region of the country, marriages are typically governed by Islamic law, whereas those in the southern region are regulated by statutory law (Women Living Under Muslim Laws, 2013). In cases where couples enter marriage under legal conditions, traditional rules often take precedence over personal matters or issues.

There is no prescribed minimum age for marriage in most common law frameworks throughout Nigeria (Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, 2006). However, the National Policy on individuals within the country prohibits parents from facilitating weddings for girls under the age of 18. Cultural beliefs about underage weddings in Nigeria are influenced by traditional laws (WARDC Women’s Advocates Research and Documentation Centre and WACOL Women’s Aid Collective, 2003). Various justifications have been offered to support this cultural practice, including the reduction of promiscuity, promotion of community cohesion and welfare, and religious sanctification of such unions (Bamgbose, 2002).

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened child marriages among vulnerable populations including girls. While it is difficult to measure the exact impact, research and stories indicate that the pandemic has worsened the situation. In Nigeria, child marriage was a problem before COVID-19 (Musa et al., 2021), and the closure of schools and increased poverty have made life more difficult for young women. Although the number of girls married during the pandemic is unknown, pre-COVID data suggests a potential negative impact on already-married children in the near future (UNICEF, 2021b). The harmful effects of marriage on Nigeria’s youth and economic development have long been a concern (Musa et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation: many families face extreme financial hardships due to exclusions and pressure to marry off girls. Numerous causes, such as school closures and cases of sexual and gender-based violence, account for the high rate of early marriages in Nigeria (Musa et al., 2021).

The COVID-19 lockdown in Nigeria has led to an increase in early marriages and teenage pregnancies among FulaniFootnote 2 females, as many have been forced to abandon their education during the pandemic (BBC NEWS, 2021). This issue persists unless authorities and communities take joint action to address it (Musa et al., 2021). A study by Yukich et al. (2021) found that without preventative programming, the impact of the pandemic on child marriages will continue to increase in Nigeria. However, if successful programming is implemented, the situation will revert to its original pattern sometime between the years 2030–2035.

Bangladesh

In Bangladeshi society, families face pressure to marry their young daughters before they turn 18. Parents worry about the consequences of not adhering to this norm, and those with steady government or overseas employment are considered ideal candidates. Due to the scarcity of suitable partners, families may view arranging a marriage for a young woman as beneficial if an advantageous opportunity arises. Families may prioritize investing in their children’s future to secure their financial well-being later in life, particularly during times of financial hardships. Cultural norms often result in girls moving away upon marriage, leading families to invest more in boys’ education. Societal restrictions limit girls’ opportunities to gain employment.

Due to the high incidence of sexual misconduct and assault committed against adolescent females, marriage is often seen to reduce the risk of sexual violence experienced by these young women. Additionally, parents and households are increasingly concerned about the dangers associated with technology, including the potential for harassment and unethical behavior, such as extramarital affairs and premarital sex (Ferdous et al., 2019).

Bangladesh has achieved notable progress in reducing the prevalence of child marriages in recent decades. This accomplishment was highlighted in 2017 by amendments made to the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929. Since the 1980s, legislation has prohibited the marriage of girls under the age of 18 and boys under the age of 21. Recent revisions have focused on implementing preventive measures to discourage, regulate, and document child marriage (The Daily Star, 2023).

Despite this progress, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a surge in teenage weddings in Bangladesh, threatening the commitment to end all forms of child marriages by 2030. A study conducted by Afrin and Zainuddin (2021) found that the increase in child marriages in Bangladesh is attributable to two pandemic-induced factors: poverty and prolonged school closures. The incidence of child marriages has increased by at least 13% because of school closures necessitated by the pandemic across the country, with many cases going unreported (Hossain et al., 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on girls’ physical and emotional well-being, educational opportunities, and the economic conditions of their families and communities. According to the empirical literature and theories on the determinants of child marriage, such disruptions increase girls’ vulnerability to becoming child brides (UNICEF, 2021b).

Concluding discussion

This study was designed to examine the impact of COVID-19 on early marriages. Our assessment of the literature indicates that the pandemic has had a substantial impact on the marriages of young boys and girls, both favorably and adversely. Marriage and singlehood are seen differently in Asian and Western cultures. Despite the growing Western acceptance of marriage as a matter of choice, many Asian countries, including Indonesia, still regard marriage as a religious or communal responsibility (Himawan, 2019).

Research on the correlation between early marriage and intimate partner violence (IPV) in developing countries has yielded mixed findings. Studies conducted in other nations, including Vietnam, have revealed that women are more likely than men to experience early marriage and IPV (Le et al., 2013).

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to several factors contributing to the marriage of young male and female children. These include economic hardship within households (Banati et al., 2020; Bahl et al., 2021; Chowdhury, 2021; Musa et al., 2021; Rahiem, 2021), inability to provide basic necessities (Rahiem, 2021; Baird et al., 2022), extended school closures (Amin et al., 2020; Deane, 2021; Musa et al., 2021), traditional laws and customs (Jones et al., 2020; Rahiem, 2021), social breakdown (Banati et al., 2020), lack of social support (Jones et al., 2020; Bahl et al., 2021; Deane, 2021; Musa et al., 2021), and parental death (Deane, 2021; Hossain et al., 2021). The pandemic has also directly contributed to some cases of voluntary marriage, such as to escape boredom (Rahiem, 2021), to manage stress (McNulty et al., 2023), to continue education (Rahiem, 2021), to address loneliness (Candel and Jitaru, 2021), and to sustain pre-pandemic intimate relationships (Komura and Ogawa, 2022). Moreover, the pandemic has negatively impacted the marriage prospects of young males and females by limiting wedding services, restricting public gatherings, closing wedding venues (Wagner et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021; Komura and Ogawa, 2022; Nursetiawati et al., 2022), and exacerbating economic hardship (Banati et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021).

The COVID-19 lockdown has caused the prolonged closure of schools, leading to a lack of interest in studies among teenagers and families facing financial difficulties, resulting in some young children opting for early marriage as an alternative (Rahiem, 2021; Chowdhury, 2021; Amin et al., 2020; Deane, 2021). Early marriages were also encouraged by local traditional laws and a desire to sustain pre-COVID romantic relationships (Komura and Ogawa, 2022; Candel and Jitaru, 2021; Rahiem, 2021). During the lockdown, social services and support were unavailable to girls, making it difficult for them to prevent early marriage (Banati et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2020; Deane, 2021; Musa et al., 2021; Esho et al., 2022). These factors contributed to the increase in the marriage rate during the COVID-19 period.

The pandemic has had a significant impact on the marital relationships of adolescent men and women with both beneficial and adverse consequences. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to several factors, including economic hardship, inability to meet basic needs, prolonged closure of schools, adherence to traditional laws and customs, social disintegration, lack of social support, and the death of parents, which have contributed to the marriage of young boys and girls. The economic and cultural perspectives of developing countries in the South differ from those of developed countries in the North. Unlike in countries in the South, early marriage is prohibited and rarely occurs in Western countries due to social and legal safeguards. Although research indicates a decline in marriage in developed countries during the pandemic, specific age groups experiencing this decline have not been identified. Further research is needed to explore this issue. Asian and Western cultures have different views on marriage.

In many Asian countries, marriage is still seen as a religious or cultural duty despite the Western view that marriage is a personal decision (Himawan, 2019). Furthermore, the negative association between unemployment and marriage rates in industrialized nations implies that both male and female employment are significantly affected during economic crises. The number of young individuals getting married during COVID-19 has decreased because of employment losses caused by the pandemic. However, some studies indicate a different correlation, according to which marriage is seen as a defense against difficult economic conditions in emerging nations (González-Val and Marcén, 2018). Women’s families may take advantage of their daughters’ weddings to relieve financial strain. Families of men may see marriage as a way to compensate for financial setbacks by using the bride’s dowry (Ahmed, 2012).

Limitations and recommendations

It is difficult to quantify and estimate whether the COVID-19 pandemic has had an increasing or decreasing impact on early marriages in different countries with very different socioeconomic and cultural dimensions. As there is little information on early marriage and COVID-19 infections in many countries, particularly developing countries, it is difficult to make generalizations applicable to particular countries. In particular, predicting the long-term effects of the pandemic on girls’ early marriages is difficult. Therefore, mixed studies combining qualitative and quantitative methods are needed to examine the effects of the pandemic on marriages, including early marriages in different age cohorts, in terms of gender. Future studies can also inform developing countries about how other countries have addressed the effects of COVID-19 on adolescents. Long-term studies can provide more insights into these effects over time. This understanding could help to identify patterns in cases where a pandemic of the same type occurs in the future.

It is critical to adapt and improve child protection initiatives, social programs, social protection services, education initiatives, and poverty reduction strategies to ensure the safety and well-being of girls and prevent early marriage. Ensuring that low-income families have access to opportunities and resources is a top priority. Governments in developing countries, especially rural areas, require increased funding and access to social security programs and educational opportunities. Campaigns to educate parents and other powerful people about the detrimental effects of child marriage and the need for girls’ education are essential, as are laws prohibiting child marriage. To effectively launch a campaign against child marriage, a coordinated effort is needed from various groups, such as government agencies, communities, civil society organizations, nonprofit organizations, and religious leaders.

Data availability

This study is based only on the relevant literature and is a review article.

Notes

Informal Union means socially or religiously accepted but legally unaccepted marriage.

Fulani females are of Fulani origins and live in Fulani areas. Fulani females are primarily found in the Northern Region of Nigeria, and Fula is their first language.

References

Afrin T, Zainuddin M (2021) Spike in child marriage in Bangladesh during COVID-19: Determinants and interventions. Child Abuse Negl 112

Ahmed N (2012) Gender and climate change in Bangladesh: The role of institutions in reducing gender gaps in adaptation programs. Soc Dev Paper. Available from: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/27416

Ahmed MNQ, Chowdhury MTA, Ahmed KJ, Haq SMA (2022) Indigenous peoples’ views on climate change and their experiences, coping and adaptation strategies in south Asia: a review. In: Mbah MF et al. (eds). Indigenous methodologies, research and practices for sustainable development, world sustainability series. Springer

Ahmed MNQ, Lalin SAA, Ahmad S (2023) Factors affecting knowledge, attitude, and practice of COVID-19: a study among undergraduate university students in Bangladesh. Hum Vaccin Immunother. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2023.2172923

Alan Guttmacher Institute (1998) Into a new world: young women’s sexual and reproductive lives. New York

Alola AA, Arikewuyo AO, Akadiri SS, Alola MI (2020) The role of income and gender unemployment in divorce rate among the OECD countries. J Labor Soc. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/lands.12460

Amin S, Rob U, Ainul S, Hossain M, Noor FR, Ehsan I, et al. (2020) Bangladesh: COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, practices and needs—responses from three rounds of data collection among adolescent girls in districts with high rates of child marriage. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UBZXWD

Baird S, Murphy M, Seager J, Jones N, Malhotra A, Alheiwidi S et al. (2022) Intersecting disadvantages for married adolescents: life after marriage pre-and post COVID-19 in contexts of displacement. J Adolesc Health 70(3):S86–S96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.12.001. Available from

Bamgbose O (2002) Customary law practices and violence against women: The position under the Nigerian legal system. Paper presented at 8th International Interdisciplinary Congress on Women hosted by Department of Women and Gender Studies, University of Makerere, July, p. 4

Banati P, Jones N, Youssef S (2020) Intersecting vulnerabilities: the impacts of COVID-19 on the psycho-emotional lives of young people in low-and middle-income countries. Eur J Dev Res 32(5):1613–1638. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00325-5

Bahl D, Bassi S, Arora M (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on children and adolescents: early evidence in India. ORF Issue Br. Available from: https://poshancovid19.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ORF_IssueBrief_448_Covid-Children-Adolescents.pdf

Bawono Y, Suminar DR, Hendriani W (2019) Low education and early marriage in Madura: a literature review. J Educ Dev 7(3):166–172. Available from: https://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/index.php/jed/article/view/29283/14925

BBC NEWS (2021) COVID child brides: ‘My family told me to marry at 14.’ BBC NEWS

Black M (2000) Growing up alone: the hidden cost of poverty. UNICEF UK

Bosquet EM, Englund MM, Egeland B (2018) Maternal childhood maltreatment history and child mental health: mechanisms in intergenerational effects. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 47:S47–S62

BRAC (2020) COVID-19 will change many women’s lives forever in Bangladesh. Available from: http://blog.brac.net/covid-19-will-change

Candel OS, Jitaru M (2021) COVID-19 and romantic relationships. Encyclopedia 1(4):1038–1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia1040079

Carter S, Moncrieff IS, Akilimali PZ, Kazadi DM, Grépin KA (2022) Understanding the broader impacts of COVID-19 on women and girls in the DRC through integrated outbreak analytics to reinforce evidence for rapid operational decision-making. Anthropol Action 29(1):47–59. https://doi.org/10.3167/aia.2022.290106

Chari AV, Heath R, Maertens A, Fatima F (2017) The causal effect of maternal age at marriage on child wellbeing: evidence from India. J Dev Econ 127:42–55

Chowdhury MM (2021) Violence against women during COVID-19 in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Multidiscip Sci Res 3(1):45–59. https://doi.org/10.46281/bjmsr.v3i1.1113

Cousins S (2020) 2⋅5 million more child marriages due to COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 396(10257):1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32112-7

Deane T (2021) Marrying young: limiting the impact of a crisis on the high prevalence of child marriages in Niger. Laws 10(3):61. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/laws10030061

Esho T, Matanda DJ, Abuya T, Abebe S, Hailu Y, Camara K et al. (2022) The perceived effects of COVID-19 pandemic on female genital mutilation/cutting and child or forced marriages in Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia and Senegal. BMC Public Health 22(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13043-w

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D et al. (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE). Am J Prev Med 14:245–258

Ferdous DS, Saha P, Yeasmin F (2019) Preventing child, early, and forced marriage in Bangladesh: Understanding socio-economic drivers and legislative gaps. Creating spaces. OXFAM Policy Pract. https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/preventing-child-early-and-forced-marriage-in-bangladesh-understanding-socio-ec-620881/

Ghaznavi C, Kawashima T, Tanoue Y, Yoneoka D, Makiyama K, Sakamoto H et al. (2022) Changes in marriage, divorce and births during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. BMJ Global Health 7(5):e007866. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021007866

Ghosh R, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, Dubey S (2020) Impact of COVID -19 on children: Special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatr 72(3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05887-9

Girls Not Brides (2020) COVID-19 and child, early and forced marriage: an agenda for action. Accessed November 5, 2020. Available from: https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/04/COVID-19-and-child-early-and-forced-marriage_FINAL-3.pdf

González-Val R, Marcén M (2018) Unemployment, marriage and divorce. Appl Econ 50(13):1495–1508. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2017.1366642

Gupta S, Jawanda MK (2020) The impacts of COVID-19 on children. Acta Paediatrica 109(11):2181–2183. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15484

Haq SMA, Islam MN, Siddhanta A, Ahmed KJ, Chowdhury MTA (2021) Public perceptions of urban green spaces: convergences and divergences. Front Sustain Cities 3:755313. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2021.755313

Herrenkohl TI, Jung H (2016) Effects of child abuse, adolescent violence, peer approval and pro-violence attitudes on intimate partner violence in adulthood. Crim Behav Ment Health 26:304–314

Himawan KK (2019) Either I do or I must: an exploration of the marriage attitudes of Indonesian singles. Soc Sci J 56(2):220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2018.07.007

Hoehn-Velasco L, Balmori de la Miyar JR, Silverio-Murillo A, Farin SM (2023) Marriage and divorce during a pandemic: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on marital formation and dissolution in Mexico. Rev Econ Household. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-023-09652-y

Hossain MJ, Soma MA, Bari MS et al. (2021) COVID-19 and child marriage in Bangladesh: emergency call to action. BMJ Paediatrics Open 5:e001328. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001328

Human Rights Watch (2012) “I had to run away’: the imprisonment of women and girls for ‘moral crimes’ in Afghanistan.” 28 March 2012. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4f787d142.html

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (2006) Nigeria: Forced marriage among the Yoruba, Igbo, and HausaFulani; prevalence, consequences for a woman or minor who refuses to participate in the marriage; availability of state protection

Jeffreys S (2009) The industrial vagina: the political economy of the global sex trade. Routledge

Jones N, Gebeyehu Y, Gezahegne K, Iyasu A, Workneh F, Yadete W (2020) Listening to young people’s voices under COVID-19: Child marriage risks in the context of COVID-19 in Ethiopia. Gender Adolesc: Global Evidence: London, UK. Available from: https://www.gage.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/GAGE-Covid-19-Ethiopia-child-marriage.pdf

Khanom K, Islam Laskar B (2015) Causes and consequences of child marriage—a study of Milannagar Shantipur Village in Goalpara District. Int J Interdiscip Res Sci Soc Culture 1(2):2395–4335

Kim J, Kim T (2021) Family formation and dissolution during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from South Korea. Global Econ Rev 50(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1226508X.2021.1874466

Komura M, Ogawa H (2022) COVID-19, marriage, and divorce in Japan. Rev Econ Household 20(3):831–853. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09609-7

Lang AJ, Gartstein MA, Rodgers CS, Lebeck MM (2010) The impact of maternal childhood abuse on parenting and infant temperament. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 23:100–110

Le MTH, Tran TD, Nguyen HT, Fisher J (2013) Early marriage and intimate partner violence among adolescents and young adults in Viet Nam. J Interpers Violence 29(5):889–910. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513505710

Mahato SK (2016) Causes and consequences of child marriage: a perspective. Int J Sci Eng Res 7(7):698–702. https://doi.org/10.14299/ijser.2016.07.002

Malinen S (2015) Understanding user participation in online communities: a systematic literature review of empirical studies. Comput Human Behav; 46:228–238

Mangeli M, Rayyani M, Cheraghi MA (2017) Factors that encourage early marriage and motherhood from the perspective of Iranian adolescent mothers: a qualitative study. World Fam Med J/Middle East J Fam Med 15(8):67–74. Available from:https://doi.org/10.5742/mewfm.2017.93058

Manning WD, Payne KK (2021) Marriage and divorce decline during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case study of five states. Socius 7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231211006976

Manusher Jonno Foundation (2020) Violence against women and children: COVID 19. A telephone survey. Available from: http://www.manusherjonno.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Final-Report-ofTelephone-Survey-on-VAW-June-2020.pdf

McDougal L, Jackson EC, McClendon KA, Belayneh Y, Sinha A, Raj A (2018) Beyond the statistic: Exploring the process of early marriage decision-making using qualitative findings from Ethiopia and India. BMC Women’s Health 18(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0631-z

McNulty JK, Hicks LL, Turner JA, Meltzer AL (2023) Leveraging smartphones to observe couples remotely and illuminate how COVID-19 stress shaped marital communication. J Fam Psychol Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0001035

Mehra D, Sarkar A, Sreenath P, Behera J, Mehra S (2018) Effectiveness of a community based intervention to delay early marriage, early pregnancy and improve school retention among adolescents in India. BMC Public Health 18(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5586-3

Musa SS, Odey GO, Musa MK, Alhaj SM, Sunday BA, Muhammad SM, Lucero-Prisno DE (2021) Early marriage and teenage pregnancy: the unspoken consequences of COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. Public Health Pract 2:100152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100152

Nursetiawati S, Siregar JS, Josua DP (2022) The new implementation of urban wedding during the COVID-19 pandemic in improving families environmental adaptation. J Posit Psychol Wellbeing 6(1):2283–2292. https://www.journalppw.com/index.php/jppw/article/view/2994/1954

Pathak S, Frayer L (2020) Child marriages are up in the pandemic. Here’s How India tries to stop them. NPR. Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/11/05/931274119/child-marriages-are-up-in-the-pandemic-heres-how-india-tries-to-stop-them

Paul P, Mondal D (2020) Child marriage in India: a human rights violation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac J Public Health1–2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539520975

Population Council (2004) “Child marriage briefing: Nigeria.” Available at: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/briefingsheets/NIGERIA_2005.pdf

Population Reference Bureau (PRB) (2003) “2003 World Population Data Sheet”. PRB, Washington, DC

Rahiem MD (2021) COVID-19 and the surge of child marriages: a phenomenon in Nusa Tenggara Barat, Indonesia. Child Abuse Neglect 118:105168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105168

Saha B, Atiqul Haq SM, Ahmed KJ (2023) How does the COVID-19 pandemic influence students’ academic activities? An explorative study in a public university in Bangladesh. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:602. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02094-y

Save the Children (2020) Accessed from https://www.savethechildren.net/news/covid-19-places-half-million-more-girls-risk-child-marriage-2020

Sezgin AU, Punamäki R (2020) Impacts of early marriage and adolescent pregnancy on mental and somatic health: the role of partner violence. Arch Womens Ment Health 23:155–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-019-00960-w

Shukla S, Ezebuihe JA, Steinert JI (2023) Association between public health emergencies and sexual and reproductive health, gender-based violence, and early marriage among adolescent girls: a rapid review. BMC Public Health 23:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15054-7

Sifat RI (2020) Sexual violence against women in Bangladesh during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatry 54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102455

Tahirih Justice Center (2018) Child marriage in the United States: a serious problem with a simple first-step solution. Tahirih Justice Center

The Daily Star (2023) Did COVID-19 make child marriage in Bangladesh worse? Published in March 17:2023

UNDP (2015) Human Development Report 2015. United Nations Development Programme. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2015_human_development_report.pdf

UNESCO (2020) COVID-19 school closures around the world will hit girls hardest. March 31 https://en.unesco.org/news/covid-19-school-closures-around-world-will-hitgirls-hardest

UNICEF (2001) Early marriage. Innocent digest; 7. UNICEF

UNICEF (2005) Early marriage: a harmful traditional practice. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Early_Marriage_12.lo.pdf

UNICEF (2014) Ending child marriage: progress and prospects. UNICEF, New York

UNICEF (2021a) 10 million additional girls at risk of child marriage due to COVID-19[Online], https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/10-million-additional-girls-risk-child-marriage-due-covid-19-unicef

UNICEF (2021b) COVID-19: a threat to progress against child marriage. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). https://data.unicef.org/resources/covid-19-a-threat-to-progressagainst-child-marriage/

UNICEF (2023) Child marriage. Child marriage threatens the lives, well-being and futures of girls around the world. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/protection/child-marriage

Wagner BG, Choi KH, Cohen PN (2020) Decline in marriage associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Socius 6:2378023120980328. https://doi.org/10.1177/237802312098032

Wan C, Shen GQ, Choi S (2021) Underlying relationships between public urban green spaces and social cohesion: a systematic literature review. City Cult Soc 24:100383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2021.100383

WARDC (Women’s Advocates Research and Documentation Centre) and WACOL (Women’s Aid Collective). (2003) Sharia and women’s human rights in Nigeria: Strategies for action”. WARDC. p. 69

Wijeyesekera R (2011) Assessing the validity of child marriages contracted during the war: A challenge in postwar Sri Lanka. Annual Research Symposium, 2011, University of Colombo. Available at: http://www.cmb.ac.lk/?page_id=2782

Women Living Under Muslim Laws (2013) Child, early and forced marriage: A multi country study. A Submission to the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OCHCR). chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/ForcedMarriage/NGO/WLUML2.pdf

World Marriage Patterns (2000) Wallchart, UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs

Yukich J, Worges M, Gage AJ et al. (2021) Projecting the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child marriage. J Adolesc Health 69:S23–S30

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shah Md. Atiqul Haq: conceptualization, literature review, methodology, formal analysis, supervision, original draft preparation, reviewing, editing, and finalizing. Mufti Nadimul Quamar Ahmed: literature review, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, original draft preparation, reviewing, editing, and finalizing. Shamim Al Aziz Lalin: literature review, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, original draft preparation, reviewing, editing, revising, and finalizing. Arnika Tabassum Arno: literature review, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, original draft preparation, reviewing, editing, revising and finalizing. Khandaker Jafor Ahmed: literature review, methodology, formal analysis, original draft preparation, reviewing, editing, and finalizing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not include any studies involving human participants by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This study did not include any human participants; therefore, informed consent was not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Atiqul Haq, S.M., Ahmed, M.N.Q., Lalin, S.A.A. et al. Early marriage of girls in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 697 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03085-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03085-3