Abstract

This qualitative study was conducted to assess the responses of emerging adults with pre-existing mood and anxiety disorders to the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients from the First Episode Mood and Anxiety Program in London, Ontario, Canada, which treats individuals aged 16–29 with mood and anxiety disorders, were invited between April 16th – 21st, 2021 to complete a survey on their current emotional states, activities and coping. Responses were analyzed using thematic analysis. A thematic analysis identified the theme of “Languishing,” among responses comprised of 3 organizing subthemes: “Dominance of Negative Emotion,” “Waiting and Stagnating,” and “Loss of Opportunity.” This study suggests that emerging adults with pre-existing mental illness languished as the pandemic and associated restrictions persisted. Emphasis on “Coping through Intentional Action,” a separate theme identified among those coping well, may be protective for this group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals with mood and anxiety disorders have been at risk of developing additional mental illnesses, and of deterioration of existing disorders (Robillard et al., 2021). Emerging adulthood is a developmental period, sometimes identified as between 18 to 25 years of age, characterized by specific developmental tasks including exploring one’s identity and re-organizing relationships in line with one’s emerging sense of values (Nelson, 2021). Emerging adults were reported to be at higher risk of developing mood and anxiety difficulties prior to the pandemic, with over half of US adults aged 18–24 in a general population sample reporting symptoms consistent with a depressive disorder or anxiety disorder (Czeisler et al., 2020). Emerging adults were initially thought to be disproportionately affected, particularly in the early waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, (American Psychological Association, 2020) though more recent literature on the longitudinal impact of the pandemic on this group has been mixed (Sun et al., 2023). While many emerging adults regained stability as the pandemic progressed into 2021, a sizable minority experienced ongoing deterioration (Paton et al. 2023). Deterioration appeared to be more consistent in emerging adult cohorts who had a pre-existing heightened level of distress prior to the pandemic (Shanahan et al. 2022), and in cohorts with pre-existing mental illness (Thorpe & Gutman, 2022, Concerto et al., 2022, Paton et al., 2023).

As compared to the general population (Ettman et al., 2020), emerging adults reported similar feelings of hopelessness and loneliness, correlating with the increased prevalence of depressive symptoms (Takács et al., 2023). Similarly, emerging adults identified fears of infection, fears of death, economic and educational uncertainties, and loss of contact with others (Cao et al., 2020, Son et al., 2020, Wammes et al., 2022), correlating with an increased prevalence of anxiety. Aside from educational uncertainty specific to the post-secondary population, these are similar to challenges experienced by the general adult population (Brooks et al., 2020, Giorgi et al., 2020).

Emerging adults in post-secondary education were broadly affected by pandemic restrictions and the switch to online schooling. Lifestyle disruptions such as decreased physical activity and decreased socialization were commonly reported among post-secondary students (Romero-Blanco et al., 2020). Screen time also increased, even excluding time spent on classes or work (Giuntella et al., 2021). Social isolation and disturbance to typical educational routines were associated with declining psychological well-being among university students (Varadajan et al., 2021, Panda et al., 2020). Sleep quality and quantity also decreased (Marelli et al., 2021, Tahir et al., 2021). Similarly, increased substance use was reported among emerging adults in post-secondary school during the early pandemic (Lechner et al., 2020, White et al., 2020). As the pandemic progressed from the first wave to the second, emerging adults in university expressed greater difficulty in studying, and more concern over their academic future, not less (La Rosa & Commodari, 2023). Though substance use (Pocuca et al. 2022, Pellham et al. 2022) and overall well-being (Paton et al., 2023, Sun et al., 2023) of some cohorts appeared to normalize as the pandemic continued, the formation of dysfunctional habits may have contributed to ongoing vulnerability even as lockdowns themselves subsided.

Emerging adults may have also been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 related stressors due to their developmental stage (Theron et al., 2021). Typical developmental tasks in emerging adulthood include exploring one’s identity and re-organizing relationships in line with one’s emerging sense of values (Nelson, 2021). While emerging adulthood is highly heterogenous, it is commonly associated with a number of material markers such as completing formal education, choosing a vocation, becoming financially self-sufficient, and living independently (Nelson, 2021). Yet the pandemic was associated with broad disruptions to education, employment, and financial well-being, particularly for emerging adults. The rapid shift from in-person to online learning was associated with increased depression and anxiety symptomatology, particularly among post-secondary students (Xu, Wang, 2022). Similarly, emerging adults tend to be less well-resourced, and in many countries were disproportionately affected by pandemic-associated job-loss and income loss (Li et al., 2023). These changes may have limited the ability of emerging adults to attain material markers typically associated with emerging adulthood and to accomplish the developmental tasks of emerging adulthood (Onyeaka et al., 2021).

Individuals who experience mental health challenges are well positioned to describe the impact of the pandemic on their circumstances and symptomatology. At the time of study, little was known about the response of emerging adults with pre-existing mental illness to COVID-19. Much of the existing literature has focused on the acute impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, but less research has been done on the response of emerging adults with pre-existing mental illness to the prolonged stressors of COVID-19. Input from such individuals has been identified as a key priority in COVID-19 mental health research (Holmes et al., 2020, Kaufman et al., 2020). This qualitative study, therefore, aimed to broadly describe the responses of emerging adults with pre-existing mental illness to the “third wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic, occurring between March – April 2021, in hopes of characterizing the response of this population to this prolonged societal stressor.

Methods

Setting

The First Episode Mood and Anxiety Program (FEMAP) is an outpatient mental health service in London, Ontario, Canada that provides treatment to emerging adults (EAs) starting at 16–25 years of age. FEMAP patients had minimal engagement with mental health treatment prior to their enrollment. The program, its patients, and related outcomes, are described elsewhere (Arcaro et al., 2017; Arcaro et al., 2019; Armstrong et al., 2019; Summerhurst et al., 2017; Summerhurst et al., 2018). We developed a system for monitoring symptoms and functioning of patients during initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic mandatory closures (Osuch et al., 2022), and conducted a previous qualitative analysis regarding patients’ responses to the first wave of the pandemic (Wammes et al., 2022).

Approximately one year into the local pandemic response, a third pandemic lockdown was initiated in Ontario. During this wave of the pandemic, public health guidance in this province discouraged individuals from socializing outside of their household, and retail services were subject to capacity limits and restricted hours of operation. COVID vaccinations were provided to high-risk groups, such as the elderly, in select Canadian cities, but were not widely available to individuals aged 16–25.

At the beginning of this lockdown, all active patients of FEMAP were invited to participate in a survey about their experiences. Questionnaires were sent from April 16th to 21st, 2021.

Procedure

All participants were invited to participate via email containing an invitation to complete questionnaires online using REDCap electronic data capture tool (Harris et al., 2009) hosted at Lawson Health Research Institute. Willing participants signed electronic informed consent at the time of invitation before any data were collected. All documents and procedures were approved for use by the Human Research Ethics Board at Western University in full accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients completed an abbreviated version of the Pandemic Response Questionnaire (PRQ) designed at FEMAP, as well as other symptom and functional measures (described in Osuch et al., 2022). In this questionnaire, titled “Covid19 Pandemic Questionnaire April 2021,” participants were asked to reflect on their mood in the past week, and changes to their work, schooling, and finances specifically due to COVID-19. At the end of the questionnaire, participants were provided a single open text box field to answer the following prompt:

If you care to elaborate on:

-

how you are feeling,

-

what you are doing,

-

your current coping methods,

-

what you are looking forward to when things are “back to normal”,

please feel free to do so here:

If you do not wish to answer please write “I do not wish to answer” in the textbox provided

Data analysis

We used the descriptive qualitative approach of thematic analysis to analyze responses (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). Since we did not know how emerging adults were affected at this period of the COVID-19 health crisis, our goals were primarily to describe and organize their responses (Sandelowski, 2000; Sandelowski, 2010). As we were interested in the themes that emerged, rather than their frequency, we largely avoided quantification of the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Braun & Clarke, 2021). Multiple coders on two separate teams engaged in an inductive process to minimize bias in the results (Braun & Clarke, 2021). The methodology of Nowell et al., (2017) was followed with minor variations to maintain high standards of rigor and trustworthiness. Data were analyzed using QSR NVivo software (March 2020).

The initial team of three coders reviewed the data independently, reviewing responses from a random 20% of participants to arrive at a preliminary list of codes. These codes were discussed by the team [E.A.O., A.P., M.W.] until consensus was reached. Next, this initial set of codes was used by the second team [M.W, J.R, J.C] of three coders, adding new codes where necessary, reviewing as a group, and arriving at consensus once again. After coding, themes were identified and refined in discussion with the team [J.C, M.W., and E.A.O]. They are presented below in full.

Quotes provided are listed verbatim with no grammatical alterations. Any clarification is noted in square brackets. Each quote includes the age and gender of the individual.

Results

Participants

434 emerging adults who were either active patients or waiting for services were invited to participate. 114 patients provided some response, but of these, 29 (25%) stated “I do not wish to answer,” leaving 85 responses for analysis. Table 1 outlines the age, gender, ethnicity, and level of education of these 85 individuals. Participants were predominantly female and Caucasian.

FEMAP patients have a range of mood and anxiety disorders, trauma-related conditions, with some having secondary substance use. Patients with a substance use disorder alone, developmental disorders, or psychosis-related illnesses like schizophrenia do not qualify for FEMAP and were, therefore, not a part of this study.

Respondents did not always choose to answer all four prompts, and some participants provided additional detail unrelated to the prompts. The entirety of some responses was limited to one or two sentences, thus not all prompts received the same volume of response.

Participants often reported using the few daily activities they were still permitted to engage in as a distraction to cope. Thus, the frequency of responses for the questions, “What are you doing?” and “How are you coping?” were combined Table 2.

Themes

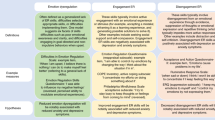

Our analysis identified two primary themes of “Languishing,” and “Coping through Intentional Action,” that seemed to describe two sets of participants, those who were doing poorly during the pandemic, and those who were doing relatively well. “Languishing” was further organized into subthemes: “Dominance of Negative Emotion,” “Waiting and Stagnating,” “Absence of Future Orientation,” and “Loss of Opportunity.” (Fig. 1, Table 3).

Theme 1: Languishing

The construct of “Languishing” is described by Keyes (2002) as the absence of emotional, psychological and social well-being. Emotional well-being is measured by the absence of negative emotion and the presence of positive emotion, while psychological and social well-being are described as measurements of an individual’s ability to thrive in their personal and social circumstances (Keyes 2002). Among other attributes, the psychological construct of well-being measures an individual’s sense of personal growth, autonomy, and mastery of their surroundings (Keyes 2002), while the construct of social well-being measures an individual’s perception that they can contribute to society and in turn find opportunities for acceptance and growth (Keyes 2002).

Each of the subthemes of “Languishing” capture a component as described by Keyes. The subtheme “Dominance of Negative Emotion” describes the presence of negative emotion and the relative absence of positive emotion consistent with a lack of emotional-wellbeing. The subtheme “Waiting and Stagnating” describes the behaviors of participants and the absence of growth, autonomy, and mastery important to psychological well-being. The subtheme “Loss of Opportunity” describes the participants’ sense that, under the influence of repeated pandemic lockdowns, there are insufficient opportunities for enrichment and growth necessary for social-wellbeing.

Subtheme 1: Dominance of negative emotion

Participant responses to the question “How are you feeling?” were dominated by negative emotions. Depression was commonly reported alongside descriptions of decreased motivation and behavioral inactivation.

“I’m bipolar and I’ve been fighting off depression the last few months. At first everything was ok but it’s gone downhill.” Female, age 29

“I have no motivation to get my lazy ass off the couch and do anything. I mostly just sleep, eat, and smoke weed, its very depressing indeed.” Male, age 18

Many patients indicated that they experienced anxiety thinking about how the pandemic would impact their future, and further unforeseen changes.

“I am anxious all the time, I feel like there is a knot in my throat and sometimes I get really intense intrusive thoughts. Sometimes I feel like there will be no end to this pandemic and then I start panicking.” Female, age 17

“I have lately been feeling very lonely, stuck, lost, and worried about my future.” Female, age 20

As expected, participants spoke at length of feeling lonely and isolated from others, particularly friends. The desire to alleviate loneliness by connecting with others was contrasted with wanting to remain apart from others due to fear of spreading COVID-19.

“I have been feeling very isolated and lonely during the pandemic without being able to lean on my friends and other support systems I had in place” Female, age 20

“I feel alone and anxious. I don’t want to be around people incase I spreed [sic] COVID.” Female, age 18

While report of low mood and anxiety would be expected given the pre-existing mood and anxiety disorders in this population, participants noted their symptomatology worsening due to the pandemic.

“I would usually consider myself a very healthy person and my anxiety was never debilitating pre-COVID. During the pandemic I feel that my mental health has quite literally plummeted and at times I feel like I am stuck in a very deep hole.” Female, age 21

Subtheme 2: Waiting and Stagnating

Participants provided detail on their behaviors in response to the questions “What are you doing?” and “How are you coping?”. Regardless of the specific behaviors, participants described a sense of purposelessness and the relative absence of self-efficacy and autonomy as they waited for the pandemic to end.

Many participants described a sense of futility in their day-to-day activities.

“feeling like ’I’m stuck in a loop and even small efforts to make progress or self care don’t matter in the long run.” Female, age 24

“My aunt died last week of cancer and I can’t attend the funeral, I can’t finish school because I don’t succeed in online courses, I’m stuck in a repetitive and dull day to day life where even the weekends offer no sense of salvation. The days and weeks have begun to blur together, and the only way I’ve been able to tell time has passed is by examining how few antidepressants i have left.” Male, age 23

While time for new hobbies was frequently mentioned as a potential upside of the first wave of the pandemic (Wammes et al., 2022), participants now reported ambivalence and fatigue regarding their hobbies.

“I am keeping myself busy with gardening and exercising, but honestly even though it is fun it still seems like a chore.” Male, age 24

“I feel a lack of purpose or drive when I’m stuck at home. I am trying to keep busy by creating new things, podcasts, art, ect but it’s hard to find the passion to doing it constantly.” Male, age 26

Some participants noted an increase in substance use for coping purposes. Participants acknowledged that these behaviors provided temporary relief but could be detrimental in the long-term.

“i have been micro-dosing mushrooms recently and it does work somewhat but it’s just a temporary thing.” Female, age 19

Given the age of the FEMAP population, many participants were working as “essential” employees (e.g., food service, retail, grocery), or enrolled in secondary or post-secondary school. At this point in the pandemic, most businesses were asked to conduct themselves virtually, save for those deemed “essential,” and secondary and post-secondary schools were operating virtually, with no in-person exposure. Yet although work and school could ostensibly provide a sense of meaning and self-efficacy, participants often implied that work and school were not a form of coping for them.

“I am working and caring for my toddler. Not engaging in activities I enjoy. No coping methods.” Female, age 26

“I feel major stress and anxiety. I hate online school did not learn a thing. it feels like there is no hope and nothing matters.” Female, age 21

Similarly, nearly half of respondents who had answered questions otherwise left the question “What are you looking forward to?” completely unanswered. The lack of response is striking, and perhaps more reflective of COVID-19’s impact on emerging adults than the content of the responses that were provided, which were often related to the restoration of “normal” societal function. This lack of response may also support the sense of futility and the absence of future orientation experienced by some participants.

Subtheme 3: Loss of Opportunity

Although not asked explicitly, respondents spontaneously described a “Loss of Opportunity” when comparing their activities prior to and during the pandemic. Participants described being unable to achieve developmental milestones that would otherwise be typical due to pandemic-related restrictions. These were often connected to negative affects, particularly sadness and grief.

“I feel as though I’m not experiencing what I should be at this age and it’s sad.” Female, age 21

“I feel sad sometimes because I am missing out on things that I should get to do as a teenager.” Female, age 16

“I want to see my friends and go outside it makes me sad that I can’t see anyone or do anything during my last summer living here.” Female, age 17

One participant linked the inability to achieve these milestones to the sense of futility described in “Waiting and Stagnating” above.

“no guarantee that it will not effect [sic] my studies if I catch Covid and can no longer come to the in-person classes, no guarentee [sic] I can move my career forward and start a family where my mother and partner are welcome in the hospital room with me to give birth, and then further have family hold the baby… it’s just floating. waiting for our lives to continue. I spent years waiting to be stable enough and now I am and I’m just floating. Waiting.” Female, age 26

Theme 2: Coping through Intentional Action

A minority of participants reported coping relatively well with the pandemic. This seemed to be associated with thoughtful and deliberate actions to accomplish goals.

“The pandemic hasn’t negatively effected [sic] my mental & emotional well-being except for a loss of hours and income regarding work. … I am currently taking steps towards personal goals, such as recently overcoming a bit of a debilitating fear of driving.” Female, age 24

“Lately being couped [sic] up at home I’ve been watching a lot of tv but most days I try to do something productive like cleaning or yard work. […] This is the first time in years that I can remember feeling stable and somewhat happy.” Female, age 23

These participants endorsed some positive affects, including gratitude or thankfulness that they had the ability to achieve their goals despite the circumstances. It was not uncommon for positive affects to be endorsed alongside negative affect.

“Most of the time I’ve been doing a lot better than I have been in previous years in regards to staying positive and grateful, but if I’m not careful I can easily spiral into a long train of paranoid thoughts… that can throw off my day. […] [I cope by] Reading, drawing (various special characters especially), talking to myself about various psychological concepts, I’ve recently started keeping a journal.” Female, age 17

“I am slowly getting back to work and I am looking forward to the weather warming up so that I can actually spend more time outside, and not couped [sic] up in my apartment all day. I am feeling okay; slightly nervous about going back to work but at least it is working from home! That makes me feel much safer and lucky in this pandemic.” Female, age 23

Some participants also reported that attending mental health services was helpful for their coping and recovery. Regardless of the exact nature of mental health service, participants seemed to be grateful for face-to-face contact and protected time with their healthcare professionals. One participant stated that meeting with mental health professionals helped her “feel productive,” in opposition to the sense of futility and purposelessness described above.

“I began addictions counseling with addictions services in January of 2021 and we try to meet weekly. This is a huge coping mechanism for me because it allows me to talk to a professional about my thoughts and feelings, as well as see another face one day a week.” Female, age 20

“My appointments with FEMAP also are very crucial to my mental stability as they allow me to leave the house and feel productive.” Female, age 23

Discussion

This study characterizes the response of emerging adults with pre-existing mood and anxiety disorders to the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Responses to the prolonged stressors of the pandemic can be described as “Languishing” and are contrasted with “Coping Through Intentional Action.” The subthemes “Dominance of Negative Emotion”, “Waiting and Stagnating,” and “Loss of Opportunity,” correspond with emotional, psychological, and social elements of languishing described by Keyes (2002), respectively.

In this study, the affective tone of respondents was overwhelmingly negative, even though three of the prompting questions (“How are you feeling?” “What are you doing?” and “How are you coping?”) were framed in an open-ended, neutral manner, and therefore not designed to elicit negative affect. Feelings of gratitude, fulfillment, or well-being were seldom expressed, though these were present for some respondents. The final question (“What are you looking forward to?”) which in theory could elicit positive affect, was left unanswered by nearly half of respondents who had otherwise provided a reply to other questions. The strong presence of negative emotion and relative absence of positive emotion is consistent with emotional languishing. Conversely, in our previous qualitative study on this population (Wammes et al., 2022), emerging adults with pre-existing mood and anxiety disorders voiced both positive and negative reactions at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although these two studies were not longitudinal, the change in emotional valence in the same demographic supports existing observations in the literature that emerging adults with pre-existing mental illness were at risk of deterioration in the pandemic (Concerto et al., 2022). It also supports the observation that these individuals represent a subgroup that deteriorated as the pandemic continued, unlike some other groups (often without mental illness or marginalization) which remained stable or improved (Paton et al., 2023).

Emerging adulthood is defined as a time-period that allows opportunities for exploration and growth prior to the commitments of adulthood (Arnett 2006; Nelson, 2021). Emerging adults often spend this time exploring and solidifying their self-identity, re-organizing and deepening relationships, and honing an educational or vocational focus that will persist into adulthood (Nelson, 2021). Successful navigation of emerging adulthood thereby provides an enduring sense of self, purpose and mastery that can constitute psychological well-being (Keyes 2002). In our sample of already vulnerable emerging adults, negative affects such as sadness and grief were commonly linked to the “loss of opportunity” and ability for exploration that is crucial for the development of mastery and identity (Arnett, 2006). Prohibitions on activities and in-person meetings restricted the ability of these emerging adults to undergo the task of relational reorganization and the process of developing one’s identity with reference to others (Layland et al., 2018), as indicated by the participant who was “sad that I can’t see anyone or do anything during my last summer living here [(before moving to college)],” and the participant who refrained from starting a family and becoming a mother on account of pandemic-related restrictions.

Navigation of emerging adulthood has also been characterized as a function of two decision-making styles: “sliding” versus “deciding” (Stanley et al., 2006; Nelson, 2021). “Sliding” is a form of decision inertia; it involves following pathways (rather than consciously making decisions), without consideration of long-term consequences on one’s identity or life trajectory, and is associated with greater long-term risk (Stanley et al., 2006; Nelson, 2021). Conversely, successful navigation of emerging adulthood is thought to be predicated on “deciding”: conscientious, deliberate decision-making in which the emerging adult practices behaviors and embodies qualities that they want to personify in adulthood, and form relationships that support these choices (Nelson, 2021).

The subtheme “Waiting and Stagnating” captures the difficulties of these vulnerable emerging adults in meeting critical developmental milestones, with psychological and social languishing as by-products. Much of the early pandemic messaging involved “staying at home” for a time-limited period. Although necessary to limit the spread of a highly transmissible illness, as the length of lockdowns increased many of our participants expressed that they had continued to refrain from exploring opportunities or moving forward in their education, relationships or careers given the uncertainty and difficulty in adapting to pandemic restrictions. This sort of “forced sliding” may have contributed to the prevalent feelings of helplessness in respondents who felt unable to exercise agency over their lives, contributing to the current “pandemic” of mental unwellness in youth (American Psychological Association, 2020).

Respondents also practiced “sliding” over “deciding” when coping with negative pandemic-related emotions. Commonly expressed behaviors included the adoption or escalation of substance use and the use of avoidance and distraction. Participants noted that these coping methods were temporary, yet many participants felt as if these coping methods were the only ones accessible to them, perpetuating a feeling of helplessness, purposelessness, and lack of mastery.

The final prompt (“What are you looking forward to?”) is a question that would ostensibly elicit hopes and optimism from respondents. Respondents in our previous study had hoped the pandemic would bring about “better perspective on what’s important, improved relationships and connectedness, and personal growth and improvement” (Wammes et al., 2022). Unfortunately, after a year, little over half of respondents in the current study reported experiencing or looking forward to any positive outcome. Furthermore, these was little data consistent with “better perspective on what’s important” and, if anything, participants struggled with feelings of sadness, purposelessness and loss. Aside from the few coping relatively well, there was little described by way of “personal growth and improvement.”

Although the inverse of “languishing” has been described in the literature as “flourishing,” (Keyes 2002, Concerto et al. 2022), even those doing relatively well in our sample of emerging adults with pre-existing mental health conditions did not describe the full presence of emotional, psychological, and social well-being consistent with flourishing. Nevertheless, those described as “coping through intentional action” were able to persist in setting and meeting meaningful goals, and ultimately expressed more balanced affect. The use of “coping through intentional action” is featured in some psychological treatments for mood and anxiety disorders, particularly Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Shepherd et al., 2022). In contrast to “sliding,” a focus on “deciding,” or taking intentional steps towards one’s growth and development, may counteract feelings of helplessness.

On a societal scale, if choices are restricted during a crisis, perhaps ongoing suggestions of daily “deciding” can become part of the public health message, especially during prolonged crisis. Options that promote agency on a day-to-day level were popular during the pandemic, though perhaps not adequately emphasized, and included the sourdough bread baking trend. While many derived a sense of meaning and belonging from “deciding” to stay indoors during the first wave, as the pandemic lengthened emerging adults with mental illness may have benefitted from messaging encouraging ongoing educational and vocational exploration despite pandemic restrictions. Infrastructure to support such actions would likely also have been helpful.

Such infrastructure would also have to be supportive to emerging adults and reinforcing of their agency. Many participants in this study were engaged in online work and school, but the online environment did not necessarily replicate the social relationships with peers, teachers, and/or mentors that would typically encourage and assist their personal growth, nor the sense of expectation and accomplishment it. Participants were often frustrated with online school, as they felt they could not succeed, or that it “didn’t matter,” or both. It is unclear what a sufficiently supporting infrastructure would include to reduce languishing in the context of societal crisis for vulnerable emerging adults, but our study suggests that the focus should be on engaging youth in actions that are empowering and developmentally appropriate. For example, participants noted that intentionally leaving the house for psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy appointments, and meeting their provider face-to-face, helped them “feel productive”. In the process of treating mood and anxiety disorders, mental health professionals at our treatment center support the personal growth of patients, reinforce commitment to their positive life changes, and encourage the self-determination with which this is done. It is important that emerging adults, with or without mental illness, have access to other relationships that serve these functions, whether at work, school, or home, and that public and organizational policy support this.

This study examined the response of emerging adults with pre-existing mood and anxiety disorders to the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thematic analysis revealed that many participants experienced languishing. Pandemic restrictions were undoubtedly necessary to avoid other unfavourable consequences, yet were associated with developmental stagnation and loss of social, educational, and vocational opportunities. By contrast, a subset of participants practiced “coping through intentional action” that may have insulated them from hopelessness and purposelessness. In future crises, societal interventions may involve prioritizing structures, institutions, and associated relationships that support exploration and commitment towards personal growth, particularly for those in critical developmental stages and/or with pre-existing vulnerabilities.

Limitations and future directions

The emerging adults in this study were restricted to those with pre-existing mood and anxiety disorders engaged in treatment, limiting the generalizability of the study. Further research would need to be conducted to determine to what degree emerging adults not engaged in treatment for mood and anxiety disorders experienced negative emotion, stagnation, and perceived loss of opportunity throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is important to note that many of our participants experienced their first mood or anxiety episode during the pandemic, prompting them to seek treatment at our centre, and it is likely that these challenges contributed to their decline in well-being. Furthermore, the emerging adults in this sample were predominantly female and non-Hispanic white. The experiences identified in this paper may not be representative of demographics that were less present in the sample (e.g. males, BIPOC individuals).

This study was also cross-sectional and exploratory in nature. While a previous cross-sectional study done by our group on this population would suggest emotional deterioration during the pandemic (Wammes et al. 2022), we did not ask participants about the COVID-19 pandemic’s impacts on identity formation, decision-making, and developmental trajectory a priori, nor did this study evaluate the developmental trajectory of our patients longitudinally. Future studies may provide additional insight on COVID-19’s impact on emerging adults, identify those who are most likely to experience an alteration in developmental trajectory and strengthen interventions for its re-establishment.

Data availability

The raw data, coding manuals, and materials contained in this manuscript are not openly available due to privacy restrictions set forth by the institutional ethics board, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

American Psychological Association (2020) Stress in America™ 2020: A National Mental Health Crisis. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/sia-mental-health-crisis.pdf

Arcaro J, Summerhurst C, Vingilis E et al. (2017) Presenting concerns of emerging adults seeking treatment at an early intervention outpatient mood and anxiety program. Psychol Health Med 22:978–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2016.1248449

Arcaro JA, Tremblay PF, Summerhurst C et al. (2019) Emerging adults’ evaluation of their treatment in an outpatient mood and anxiety disorders program. Emerg Adulthood 7:432–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818777339

Armstrong S, Wammes M, Arcaro J et al. (2019) Expectations vs reality: The expectations and experiences of psychiatric treatment reported by young adults at a mood and anxiety outpatient mental health program. Early Inter Psychiatry 13:633–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12550

Arnett JJ (2006) Emerging Adulthood: Understanding the New Way of Coming of Age. In: Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, US, pp 3–19

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol 18:328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE et al. (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395:912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G et al. (2020) The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res 287:112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Concerto C, Rodolico A, La Rosa VL et al. (2022) Flourishing or Languishing? Predictors of positive mental health in medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19:15814. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315814

Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E et al (2020) Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69:1049–1057. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH et al. (2020) Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 3:e2019686. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686

Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F et al. (2020) COVID-19-related mental health effects in the workplace: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:7857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217857

Giuntella O, Hyde K, Saccardo S, Sadoff S (2021) Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118:e2016632118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2016632118

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R et al. (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf 42:377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH et al. (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 7:547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

Kaufman KR, Petkova E, Bhui KS, Schulze TG (2020) A global needs assessment in times of a global crisis: world psychiatry response to the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open 6:e48. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.25

Keyes CLM (2002) The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav 43:207–222

Layland EK, Hill BJ, Nelson LJ (2018) Freedom to explore the self: How emerging adults use leisure to develop identity. J Posit Psychol 13:78–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1374440

Lechner WV, Laurene KR, Patel S et al. (2020) Changes in alcohol use as a function of psychological distress and social support following COVID-19 related University closings. Addict Behav 110:106527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106527

Li L, Serido J, Vosylis R, et al. (2023) Employment disruption and wellbeing among young adults: A cross-national study of perceived impact of the COVID-19 lockdown. J Happiness Stud 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00629-3

La Rosa VL, Commodari E (2023) University Experience during the First Two Waves of COVID-19: Students’ Experiences and Psychological Wellbeing. Euro J Investig Health, Psychol Educ 13:1477–1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13080108

Marelli S, Castelnuovo A, Somma A et al. (2021) Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on sleep quality in university students and administration staff. J Neurol 268:8–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10056-6

Nelson LJ (2021) The theory of emerging adulthood 20 years later: a look at where it has taken us, what we know now, and where we need to go. Emerg Adulthood 9:179–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696820950884

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ (2017) Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods 16:1. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069177338

Onyeaka H, Anumudu CK, Al-Sharify ZT et al. (2021) COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci Prog 104:368504211019854. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504211019854

Osuch E, Demy J, Wammes M et al. (2022) Monitoring the effects of COVID-19 in emerging adults with pre-existing mood and anxiety disorders. Early Inter Psychiatry 16:126–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.13135

Panda PK, Gupta J, Chowdhury SR, et al. (2020) Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trop Pediatr fmaa122. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmaa122

Paton LW, Tiffin PA, Barkham M et al. (2023) Mental health trajectories in university students across the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the Student Wellbeing at Northern England Universities prospective cohort study. Front Public Health 11:1188690. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1188690

Pelham WE, Yuksel D, Tapert SF et al. (2022) Did the acute impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on drinking or nicotine use persist? Evidence from a cohort of emerging adults followed for up to nine years. Addict Behav 131:107313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107313

Pocuca N, London-Nadeau K, Geoffroy M-C et al. (2022) Changes in emerging adults’ alcohol and cannabis use from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a prospective birth cohort. Psychol Addict Behav 36:786–797. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000826

Robillard R, Daros AR, Phillips JL et al. (2021) Emerging New psychiatric symptoms and the worsening of pre-existing mental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Canadian Multisite Study: Nouveaux symptômes psychiatriques émergents et détérioration des troubles mentaux préexistants durant la pandémie de la COVID-19: une étude canadienne multisite. Can J Psychiatry 66:815–826. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720986786

Romero-Blanco C, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Onieva-Zafra MD et al. (2020) Physical activity and sedentary lifestyle in university students: changes during confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:6567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186567

Sandelowski M (2000) Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 23:334–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:43.0.CO;2-G

Sandelowski M (2010) What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 33:77–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20362

Shanahan L, Steinhoff A, Bechtiger L et al. (2022) Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychol Med 52:824–833. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000241X

Shepherd K, Golijani-Moghaddam N, Dawson DL (2022) ACTing towards better living during COVID-19: The effects of Acceptance and Commitment therapy for individuals affected by COVID-19. J Contextual Behav Sci 23:98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.12.003

Son C, Hegde S, Smith A et al. (2020) Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. J Med Internet Res 22:e21279. https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

Summerhurst C, Wammes M, Arcaro J, Osuch E (2018) Embracing technology: Use of text messaging with adolescent outpatients at a mood and anxiety program. Soc Work Ment Health 16:337–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2017.1395782

Summerhurst C, Wammes M, Wrath A, Osuch E (2017) Youth perspectives on the mental health treatment process: what helps, what hinders? Community Ment Health J 53:72–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-0014-6

Sun Y, Wu Y, Fan S et al. (2023) Comparison of mental health symptoms before and during the covid-19 pandemic: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 134 cohorts. BMJ 380:e074224. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-074224

Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, Markman HJ (2006) Sliding versus Deciding: Inertia and the Premartial Cohabitation Effect. Family Relations. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00418.x

Tahir MJ, Malik NI, Ullah I et al. (2021) Internet addiction and sleep quality among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multinational cross-sectional survey. PLoS One 16:e0259594. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259594

Takács J, Katona ZB, Ihász F (2023) A large sample cross-sectional study on mental health challenges among adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic at-risk group for loneliness and hopelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord 325:770–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.067

Theron L, Levine D, Ungar M (2021) Resilience to COVID-19-related stressors: Insights from emerging adults in a South African township. PLoS One 16:e0260613. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260613

Thorpe WJR, Gutman LM (2022) The trajectory of mental health problems for UK emerging adults during COVID-19. J Psychiatr Res 156:491–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.10.068

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T (2013) Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 15:398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

Varadarajan J, Brown AM, Chalkley R (2021) Biomedical graduate student experiences during the COVID-19 university closure. PLoS One 16:e0256687. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256687

Wammes M, Summerhurst C, Demy J et al. (2022) Hopes and fears: emerging adults in mood and anxiety disorder treatment predict outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Work Ment Health 20:314–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2021.2008088

White HR, Stevens AK, Hayes K, Jackson KM (2020) Changes in alcohol consumption among college students due to COVID-19: Effects of campus closure and residential change. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 81:725–730. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2020.81.725

Xu T, Wang H (2022) High prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among remote learning students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Front Psychol 13:1103925. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1103925

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author E.A.O was responsible for study conception and design, with further methodological input from authors P.T and E.V. Data collection was conducted by E.A.O, M.W, J.D, and C.C. Coding and data analysis were conducted by J.C, M.W, J.R, A.P, and E.A.O. Draft manuscript preparation was conducted by J.C. and M.W. All authors discussed the results of thematic analysis, reviewed, and commented on the manuscript as well.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All documents and procedures were approved for use by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board at Western University in full accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with REB approval #115748. Ethical approval was sought by E.A.O and M.W. on behalf of the study team.

Informed consent

Willing participants signed electronic informed consent at the time of invitation prior to data collection. Participants received an email invitation to participate in a longitudinal study examining the effects of COVID-19 on FEMAP patients as early as April 10th, 2020, although data used in this study was collected during the “third wave,” from April 16th–21st, 2021. A Letter of Information was provided via email to participants prior to enrollment of the study. Consent was obtained using the REDCap electronic platform. Participants were able to meet with a study team member (M.W.) if they had concerns or required clarification regarding the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chitpin, J., Wammes, M., Ross, J. et al. Languishing: Experiences of emerging adults in outpatient mental health care one year into the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 802 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03247-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03247-3