Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted traditional education systems globally, with African Higher Education Institutions particularly challenged due to pre-existing infrastructural and technological limitations. This study examines the response of the University of Education, Winneba, in Ghana, to the pandemic by transitioning to online learning using the MOODLE Learning Management System and other digital platforms. This study employs a mixed-methods approach, integrating qualitative observations, quantitative data analysis, and machine learning (ML) techniques to comprehensively explore the transition to online learning at the University of Education, Winneba. Key findings indicate that while the transition enabled the continuity of education for over 92,000 students, challenges such as limited Internet access, inadequate digital literacy among faculty and students, and technical infrastructure limitations were significant barriers. The study recommends targeted investment in digital infrastructure, comprehensive training for educators, and policy reforms to support sustainable online education. This research contributes to understanding the digital transformation of education in African HEIs and offers a framework for improving resilience in future disruptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to Aheto-Tsegah [1], the development of education in Ghana is closely connected to the sociopolitical transition from the colonial era to the present day. Education in Ghana started way back in pre-colonial times (between 2000 and 500 BC) [2]. During this period, education was informal and indigenous, and knowledge and competencies were transmitted orally and through apprenticeships. This form of education was backed by a strong socio-cultural milieu, which ensured active participation in life [2]. Recent educational transformation processes have seen the education system expand from the colonial fort schools to the spread of formal education across the country, including access to free education and the inclusion of technical and vocational education. These transformations, coupled with the growing population brought in its wake dire challenges in the education sector. There is a shortage of school supplies and qualified teachers, packed classrooms, and inadequate water and sanitation infrastructure [3]. The goal of Ghana's recent free secondary education program was to reduce the country's high dropout rates. Every year, over 100,000 children do not move from elementary to secondary education because their parents are unable to pay the expenses, according to Mohammed and Kuyini [4]. Furthermore, even with higher enrollment rates in recent years, reading skills and learning results frequently remain subpar. For example, in 2020, the West African Examination Council tests resulted in 44 percent of high school students failing. Gender inequality and differences in rural–urban access to education are still on the rise. The Ghana Tertiary Education Council reports that as of September 2019, there were 208 accredited postsecondary educational institutions in the nation. Ten of the colleges were public, 81 were private, 38 were nursing schools, 46 were teacher-training colleges (colleges of education), and 81 were private universities offering degree programs. The University of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, University of Cape Coast, University of Education, Winneba, and Ashesi University were the top five universities in Ghana according to the Times Higher Education Worldwide University Ranking 2019 [5]. As of 2019, the tertiary net enrollment rate was 17.23%, which is quite low considering the number of universities in the nation [6]. The demand for university placement is significantly higher than the supply, making it extremely competitive. This trend is predicted to worsen in the upcoming years as secondary school enrollment and attainment levels rise. However, to supplement conventional face-to-face teaching methods and increase university access before the global pandemic, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), several colleges throughout the country implemented Distance Education (DE) as a supplemental mode of instruction. Ghana reported its first two COVID-19 infections on March 12, 2020. On March 15, 2020, the President of the Republic of Ghana announced several steps to stop the virus's spread within the country [7]. The government's measures, which included tighter cleanliness regulations and social isolation, were intended to slow the virus's spread. The President issued an executive order to close schools as of March 16, 2020. All university schedules were disrupted by this order, and for the University of Education, Winneba (UEW) to successfully conclude the academic year, creative solutions to the COVID-19 Pandemic had to be found. UEW used online learning and tests from March 15 to July 31, 2020, to finish coursework for the second semester of the 2019–2020 school year. UEW used the MOODLE Learning Management System (LMS) and additional social media apps to facilitate remote learning interactions and activities for approximately 400 faculty members and 92,000 students.

Furthermore, drastic improvements were made in the technology infrastructure and operational practices. For example, server specifications were improved to cope with the increasing load. Some governance structures at both local and national levels also helped to improve the situation by white listing and absorbing data charges for university students. Despite these laudable achievements, there are still some outstanding challenges the university has to address: One of the key challenges the university faces is Change Management, in the sense that every innovation places an extra burden on each practitioner such as learners, teachers, and technical support staff during the adoption stage. Certain technical challenges, such as system architecture, need to be addressed to make the system resilient and efficient. The third major challenge is inadequate technology competence amongst learners and teachers, which should be addressed through training in the pedagogical use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT).

The unexpected shift to virtual learning prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic exposed considerable gaps in the readiness of African Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to effectively harness digital technologies. This study explores how the UEW navigated this transition, highlighting both the challenges and the opportunities that emerged from this digital transformation. Specifically, the study addressed the following objectives:

-

I.

To assess students’ engagement and academic performance

-

II.

To assess Faculty preparedness and student outcomes

-

III.

To predict students' engagement based on infrastructure variables

In Ghana, the University of Education, Winneba (UEW) is the pioneer in teacher education development. The university specializes in conducting groundbreaking research, sharing knowledge, and participating in the creation of educational policies, in addition to providing professional training for teachers at all educational levels.

The university currently has four campuses spread around Ghana's central area, with the main campus in Winneba divided among three locations. Approximately 95,000 students are enrolled in face-to-face programs, while others are learning remotely. Additionally, the needs of the university's remote learning students are met by 20 service centers. Nonetheless, the University of Education, Winneba (UEW) has embraced blended learning over the years, employing a variety of technology-enabled delivery methods. In light of this, several instructors in traditional in-person programs have started implementing blended learning to enhance their instruction and provide more flexibility in their lectures.

The lockdown during the second semester of the 2019/2020 academic year necessitated the use of online teaching and learning, which required investment in the technical competencies of teaching staff and the acquisition of resources to aid in its implementation. The adoption of a hybrid or blended mode of instructional delivery for all academic programmes poses the following significant challenges for UEW and other universities in the country:

-

Inadequate teaching and learning facilities and equipment as well as e-resources.

-

The majority of faculty have inadequate competencies in technology skills and knowledge for developing effective online courseware and facilitation of online teaching and learning.

-

High cost of Internet connectivity and bandwidth subscription, particularly for remote learners.

-

Inadequate server space for large numbers of online students and faculty.

-

Absence of institutional policies on ICT, Educational Technology (ET) and eLearning.

-

No functional multimedia and Academic Computing Center.

This paper is structured as follows: The literature on digital education in African higher education institutions, namely during the COVID-19 epidemic, is reviewed in Sect. 2. The methodology for this study, including the techniques for gathering and analyzing data, is described in Sect. 3. The study's findings are presented in Sect. 4, which also discusses the difficulties and achievements of UEW's online learning programs. Section 5 discusses these findings in the context of broader educational challenges in Africa. Finally, Sect. 6 offers conclusions and recommendations.

2 Literature review

This section critically examines existing studies on digital education, with a focus on African HEIs. The review explores how digital learning has been integrated into educational practices, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, and identifies gaps in the current research, such as the lack of empirical studies on the effectiveness of digital learning in resource-constrained environments.

2.1 Historical context and background

This section gives a brief of the conditions of digital education in African Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) before the COVID 19 pandemic and also theories that this study is hinged on.

2.1.1 Pre-pandemic digital education in African higher education institutions

Hitherto the COVID-19 pandemic, digital education in African HEIs was characterized by limited integration and usage. Studies have shown that many African universities relied predominantly on conventional, face-to-face teaching methods [8,9,10,11]. This reliance was partly due to inadequate technological infrastructure and a lack of comprehensive digital strategies. For example, Rutayisire, et al. [12] posited that while some African institutions had introduced basic Electronic Learning platforms, these were often underutilized due to sporadic Internet access and limited digital resources and educator competencies.

The gap in digital education readiness between African HEIs and their counterparts in developed regions is significant. Nherera and Mukora [13] provide a comparative analysis, showing that institutions in North America and Europe had already implemented advanced Electronic Learning systems and robust digital infrastructure in the late 1990s. On the other hand, African HEIs face challenges such as low Internet penetration, unstable electricity, intermittent Internet connectivity, and limited access to digital devices. This disparity has been well-documented, Paschal, et al. [14], for example, accentuated that many institutions in Africa were struggling to keep pace with global trends in digital education.

2.1.2 E-readiness of institutions

E-readiness, according to Goh and Blake [15], is the degree to which a person or group of people is ready to engage in the networked world. The notion of e-readiness is relatively new, having gained momentum due to the rapid global Internet adoption and the significant advancements in the application of information and communications technology (ICT) in business and industry [16,17,18]. Developed nations have realized lately how important it is to create policies for the creation and application of new technology in all spheres of social and economic life.

The degree to which a community is prepared to participate in the interconnected global community can be characterized in this context as e-readiness. This can be determined by evaluating the community's relative progress in the areas that are most important for ICT. As of January 2021, for instance, the population of Ghana was 31.40 million, indicating an increase of 655 thousand (+ 2.1%) from January 2020 to January 2021. As of January 2021, there were 15.70 million Internet users in Ghana. Between 2020 and 2021, Ghana's Internet user base grew by 943 thousand (+ 6.4%). As a result, in January 2021, the Internet penetration rate increased to 50.0% [19].

2.1.3 Pedagogical integration of ICT

The goal of the UEW's entire program portfolio is to raise the bar for technology-assisted teaching and applications across all facets of the educational system and its procedures. How teachers can effectively use ICT to support institutional, instructional, and learning goals is a critical consideration when deciding when and how to employ technology to enhance teaching and learning. The primary goal of UEW is to train educators to attain technical expertise, develop strong interpersonal communication and ethical standards, and become knowledgeable, skilled, and capable of effectively integrating appropriate ICT tools into their teaching practices. The University's focus has been on infusing ICT throughout all of the different curricula and using ICT pedagogically in conjunction with student-led teaching methodologies.

2.1.4 Teaching and learning online

Electronic Learning, according to Jethro, Grace and Thomas [18], is a type of education where students use the Internet or other computer networks to access learning resources and communicate with peers and instructors. HEIs can employ ICTs' widespread use and inherent capability to address some of the major problems they are now experiencing, such as insufficient classrooms and resources to house and reach the ever-increasing students. In the majority of educational sectors worldwide, Electronic Learning is now the driving force behind the digital transformation [20]. Due to a shortage of lecturers, classrooms, and housing, a large number of prospective students are turned away each year, despite the growing number of students enrolled [21]. There is little doubt that present educators are up against obstacles as they attempt to instruct and prepare the next generation of students.

Recently, education reforms have put more pressure on academic staff, leaving them with less time for instruction than in the past. The traditional teacher-centred approach to teaching and learning is gradually being phased out. A more learner-centred approach has been recommended by educational researchers as the best model in contemporary times [22, 23]. Leveraging ICTs, and, in particular, Electronic Learning can help lecturers improve the effectiveness of educational strategies impeded by cultural and social situations. E-Learning has been very popular in recent times; nonetheless, its use and implementation are very different among HEIs. According to [24], Electronic Learning is gradually gaining global acceptance as an alternate means of expanding/increasing enrolment numbers in HEIs. The University of Education, Winneba, in Ghana, has decided to use Electronic Learning as a catalyst to transform UEW into a cutting-edge academic setting for higher education in Ghana after realizing the tremendous potential of the technology in comparison to the university's ever-growing student body.

2.1.5 Digital education

Digital Literacy is the ability to use ICT to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both intellectual and technical skills [17, 25]. Academic literacy with digital literacy provides students with critical skills for today’s digital and academic environments. Academic literacy teaches foundational research and writing skills, while digital literacy enhances students' abilities to find, evaluate, and ethically use online information. Together, they enable students to critically assess digital content and produce various forms of academic work, from papers to digital projects. This integration also strengthens students’ understanding of academic integrity in online spaces and prepares them for collaborative, technology-driven learning environments. E-learning, on the other hand, refers to the use of ICT tools, services, and digital content in education [26]. Studies have shown the many benefits inherent in the use of E-Learning to significantly facilitate the efficiency and effectiveness of teaching, learning, and also access to a vast repository of learning resources [24, 27,28,29]. Electronic Learning in schools is used both by students and staff in the process of exchanging information and gaining knowledge, as well as for communication and easy access to educational information at a cheaper cost.

2.2 Technological and infrastructural challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic era exposed and exacerbated existing infrastructural challenges within African HEIs. Jakoet-Salie and Ramalobe [30] conducted a comprehensive survey revealing that inadequate bandwidth and unreliable Internet access were major barriers to effective online learning. For instance, Fitria [31] describes how many students faced difficulties accessing online resources due to slow or unstable Internet connections, which hindered their ability to participate in virtual classes and complete assignments. Several case studies provide insights into how different African institutions navigated these challenges [31,32,33,34,35]. Ajibo and Ene [33] examined institutions in Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa, noting that while some were able to adapt quickly by leveraging existing digital resources, others struggled significantly. For example, Ogegbo and Tijani [36] conducted a study on a Nigerian university that faced severe limitations due to outdated hardware and insufficient technical support, resulting in a disrupted learning experience for students.

2.3 Pedagogical approaches

2.3.1 Adaptation of teaching methods

The paradigm shift to online learning during the pandemic required instructors to rapidly adapt their lesson delivery methods. According to Ajamu, et al. [37], many instructors transitioned to asynchronous learning formats, such as pre-recorded lectures and online discussion forums. While these methods provided flexibility, they also introduced challenges in maintaining student engagement. Zhang, et al. [38] also posited that asynchronous learning often resulted in lower participation rates and reduced interaction between students and instructors.

2.3.2 Effective pedagogical practices

Regnier, et al. [39] identified several best practices for online teaching that emerged during the pandemic. Effective practices include the use of interactive tools like forum discussions, quizzes and polls, and regular feedback. The study also emphasizes the importance of creating engaging and interactive content to maintain student motivation and enhance learning outcomes.

2.3.3 Faculty and student preparedness

The effectiveness of online teaching is closely tied to the level of training provided to both faculty and students. White, et al. [29] reported that many institutions did not offer adequate training programs for educators, which impacted their ability to deliver online instruction effectively. White, et al. [29] found that faculty members often lacked familiarity with digital tools and the pedagogical strategies necessary for successful online teaching. The inequality in digital literacy levels among students and faculty also posed a challenge. Siregar [40] conducted studies showing that varying levels of digital competence influenced the effectiveness of online learning. For example, his study showed that students with higher digital literacy levels were more successful in navigating online learning platforms and utilizing digital resources effectively.

2.3.4 Student engagement and outcomes

Understanding student engagement in online learning environments is crucial for evaluating the success of digital education. Getenet, et al. [41] explore various engagement metrics, including participation rates, interaction levels, and time spent on learning platforms. These metrics provide insights into how effectively students are engaging with online content and participating in virtual classes.

The impact of online learning on academic performance has been mixed. Luo, et al. [42] present evidence that while some students thrived in digital learning environments, others struggled. The study highlights how students’ performance varied based on factors such as access to resources, digital literacy, and the quality of instructional materials. This variability underscores the need for tailored support and resources to address diverse learning needs.

2.3.5 Policy and institutional response

In response to the pandemic, many HEIs revised their policies on online education. Turnbull et al. [43] analyze how institutions updated their emergency remote teaching guidelines and adapted their digital resource allocations. Turnbull et al. [43] detail the development of new policies aimed at improving the accessibility and quality of online education, including the implementation of more flexible assessment methods and increased support for students and faculty.

2.3.6 Government and policy frameworks

Government responses and policy frameworks have also played a significant role in shaping digital education. Symeonidis, et al. [44] discuss various initiatives aimed at supporting digital education, such as funding for technological infrastructure and the development of national guidelines for online teaching. Symeonidis, et al. [44] highlight how these policies have influenced institutional strategies and practices related to digital education in Europe and the US.

2.3.7 Long-term implications and emerging trends

The long-term implications of the pandemic on higher education are still evolving. Singh, et al. [45] explore potential shifts towards hybrid learning models that combine online and face-to-face instruction. This trend reflects a growing recognition of the benefits of integrating digital tools into traditional teaching methods to enhance flexibility and accessibility.

Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality (VR) hold promise for transforming digital education. Kumar [46] examine how these technologies could address existing challenges and improve the learning experience. The study discusses the potential of AI to provide personalized learning experiences and VR to create immersive educational environments.

3 Methodology

3.1 Methods

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, integrating qualitative observations, quantitative data analysis, and machine learning (ML) techniques to comprehensively explore the transition to online learning at the University of Education, Winneba (UEW). As posited by Busetto, et al. [47], observations are particularly valuable for gaining insights into actual behaviors within a specific setting, offering a more accurate understanding than relying solely on reported behaviors or opinions.

This study employed a purposive sampling technique to choose participants who were actively engaged in the transition to online learning. The sample comprised 500 students and 100 faculty members from various departments at UEW, ensuring a broad spectrum of experiences and perspectives, which enriched the dataset for subsequent analysis.

3.1.1 Data collection

3.1.1.1 Qualitative data

Participant Observation: The researchers, who also serve as lecturers at UEW, systematically documented their observations and interactions with students and faculty during the shift to online learning. These notes focused on the challenges faced, the adjustments made, and the behaviors observed in this new learning environment.

Focus Group Discussions: To gain deeper insights, focus group discussions were held with both students and faculty. These conversations explored their experiences, concerns, and recommendations regarding online learning, providing valuable qualitative data that complemented the observational findings.

3.1.1.2 Quantitative data

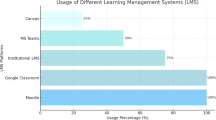

LMS Analytics: Data from the Learning Management System (LMS) were analyzed to measure key metrics, such as student engagement, participation rates, and access patterns. This quantitative data offered an objective view of how students interacted with the online learning platform.

Surveys: Structured surveys were distributed to both students and faculty, collecting feedback on their online learning experiences. These surveys included both closed-ended questions for quantifiable data and open-ended questions for additional qualitative insights.

3.2 Machine learning analysis

Predictive Modeling: To further understand student engagement and performance, machine learning techniques were applied. LMS log data were used to train predictive models aimed at identifying factors that contribute to student success or difficulties in the online learning setting. Various algorithms, such as decision trees and random forests, were tested to determine the best fit.

Clustering Analysis: Clustering algorithms, like k-means, were also used to group students based on their interaction patterns with the LMS. This analysis revealed distinct clusters of students with similar behaviours, helping to target different student needs and challenges more effectively.

3.3 Data analysis

A combination of descriptive statistics, thematic analysis, and machine learning techniques were used to analyze the data.

Descriptive Statistics: The quantitative data from the surveys and LMS analytics were examined pithily via descriptive statistics so that the trends and patterns in student engagement, participation rates, and the usage of different online learning resources can be apprised to the entire school.

Thematic Analysis: The qualitative data extracted from observations of the participants, focus group discussions, and open-ended survey responses were analyzed through thematic analysis.

This form enabled the researchers to identify recurring themes and challenges in the process of online learning, and it was able to reveal multi-faceted aspects through the participants' experience.

Machine Learning Insights: The machine learning models conducted additional analyses of the identities to the student's interaction quality and success. The research developed prediction models that mentioned success labels, while the data clustering showed the existence of different student groups. Through this, schools can deduce tailored interventions for subgroups of students with distinct characteristics.

4 Results

This section presents the findings from our analysis of the University of Education, Winneba’s (UEW) transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data includes responses from 500 students and 100 faculty members, focusing on access to technology, engagement in online learning, and overall academic performance.

4.1 Assess students' engagement and academic performance

4.1.1 Student engagement metrics

Our survey data indicate varied levels of student engagement across institutions. As shown in Table 1, engagement metrics such as participation in online discussions, attendance in live sessions, and completion of assignments vary significantly.

4.1.2 Academic performance

Figure 1 illustrates the correlation between student engagement and academic performance. Institutions with high engagement levels report higher average grades and lower failure rates compared to those with medium and low engagement.

4.1.3 Impact of engagement on performance

Analysis shows a positive relationship between engagement and performance. Students in institutions with higher engagement levels have demonstrated improved academic outcomes, as detailed in Table 2.

4.1.4 Assess faculty preparedness and student outcomes, faculty preparedness

Survey results on faculty preparedness for digital teaching reveal varying levels of readiness. Table 3 presents the proportion of faculty members who have received training and those who are comfortable with digital tools.

4.1.5 Student outcomes by faculty preparedness

Figure 2 shows that institutions with a higher proportion of fully trained faculty members report better student outcomes, including higher average grades and increased student satisfaction.

-

Fully Trained Faculty: Average Grade + 12%, Satisfaction + 20%

-

Partially Trained Faculty: Average Grade + 5%, Satisfaction + 10%

-

Not Trained Faculty: Average Grade − 5%, Satisfaction − 15%

4.1.6 Impact of training on outcomes

Table 4 highlights the correlation between faculty training and student performance metrics. Institutions with well-trained faculty exhibit better student outcomes across multiple dimensions Fig. 3.

4.1.7 Predict student engagement based on infrastructure variables infrastructure variables

To assess how infrastructure affects student engagement, we analyzed several variables, including Internet connectivity, digital resource availability, and technical support. Table 5 summarizes these variables.

4.1.8 Machine learning analysis

We employed a machine learning approach to predict student engagement levels based on infrastructure variables. The following ML models were used:

-

1.

Linear Regression: To understand the linear relationship between infrastructure variables and student engagement.

-

2.

Decision Trees: To identify non-linear patterns and interactions between different infrastructure factors.

-

3.

Random Forest: To improve prediction accuracy by combining multiple decision trees.

4.1.9 Model performance

-

Linear Regression: Achieved an R2 score of 0.65, indicating a moderate fit.

-

Decision Trees: Provided a clearer view of variable importance but had an overfitting issue.

-

Random Forest: Offered the highest accuracy with an R2 score of 0.78, showing strong predictive capability.

4.1.10 Feature importance

4.1.10.1 Predicted engagement levels

Using the Random Forest model, we predicted engagement levels based on different infrastructure scenarios. Table 6 shows the predicted engagement increases for high, medium, and low-quality infrastructure conditions.

4.1.10.2 Impact of infrastructure on engagement

The machine learning analysis confirms that improvements in infrastructure variables lead to significantly higher predicted engagement levels. Enhancing Internet connectivity, digital resources, and technical support are crucial for boosting student engagement.

4.2 Additional analysis from field notes

4.2.1 Engagement, performance, and well-being in the digital transition

4.2.1.1 Disparity in engagement and performance across demographics and disciplines

In assessing student engagement and academic performance throughout the digital transition, it became clear that significant differences appeared depending on student demographics, including factors like gender, socioeconomic status, and whether students lived in urban or rural areas, as well as their academic disciplines.

4.2.1.2 Socioeconomic disparities

Students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, particularly in rural areas, had engagement issues. For instance, these students faced issues related to unstable Internet service and the availability of digital devices. The analysis also showed that students in rural areas had 25 per cent lower engagement than their urban counterparts for participation rate in discussions and live sessions. Additionally, their homework completion rates were, on average, 15% lower and linked to a 10% drop in overall academic standards. In the implementation phase, in its early stages, a 10% increased engagement has been observed among rural students from these ongoing projects.

4.2.1.3 Gender-based engagement trends

Interestingly, female students, especially those from urban areas, demonstrated greater engagement levels than their male peers. They were more active in asynchronous learning formats, with 65% attending pre-recorded lectures and discussion forums, while only 45% of male students did the same. This increased engagement among female students also led to improved academic performance, as their average grades were 8% higher than those of male students across various disciplines.

4.2.1.4 Discipline-specific differences

Differences in engagement can also be attributed to academic disciplines. Students in Science and Technology tended to engage more with online platforms, as their coursework often required regular use of digital tools. Conversely, those studying arts and humanities faced difficulties in adjusting to the digital learning environment, resulting in lower participation in online discussions and live classes. For example, engineering students demonstrated a 20% higher engagement in live sessions, likely due to the digital skills they acquired through their studies. In contrast, social science students reported a 15% lower engagement rate, mentioning struggles with self-directed learning and finding appropriate digital resources.

4.2.2 Long-term impacts of the digital transition on educational outcomes and student satisfaction

The shift to digital learning at UEW, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, has had significant effects on educational outcomes and student satisfaction, which are likely to shape the future of higher education at the institution.

4.2.2.1 Educational outcomes

The long-term academic effects of this digital shift are varied. On one hand, students who were already comfortable with technology adapted well and, in some instances, exceeded their academic performance from before the pandemic. On the other hand, students from disadvantaged backgrounds or those lacking digital skills experienced a 10% higher failure rate compared to their peers who had reliable Internet access and prior experience with online learning.

Even with these challenges, academic flexibility has established itself as a lasting aspect of education, enabling students to select between synchronous and asynchronous learning options. This adaptability has proven especially advantageous for non-traditional students, such as working professionals, who have experienced a 20% rise in satisfaction due to the ability to access course materials whenever it suits them.

4.2.2.2 Student satisfaction

Overall, student satisfaction with digital learning is on the rise. Surveys conducted six months after the initial transition show that 72% of students preferred having digital options available even when in-person classes resumed. They valued the chance to review recorded lectures and the greater independence in managing their studies. However, students facing Internet access challenges, particularly in rural areas, voiced their dissatisfaction, with 30% reporting frustration due to frequent connectivity problems.

4.2.3 Effects of the digital transition on morale and well-being

The shift to online learning has significantly affected both student and faculty morale, as well as their overall well-being, showcasing a range of experiences.

4.2.3.1 Student morale and well-being

For numerous students, the sudden move to online learning led to feelings of isolation and anxiety, particularly for those who depended on face-to-face interactions for motivation. A survey indicated that 45% of students experienced heightened stress levels, mainly due to technical issues and challenges in engaging effectively with peers and instructors. On the other hand, 20% of students found that the flexibility of online learning enhanced their overall well-being, allowing them to juggle their studies with other responsibilities like work or family. This was especially true for mature students, who reported a 15% increase in satisfaction with their learning experience after the transition.

4.2.3.2 Faculty morale and well-being

Faculty morale also showed variation. Initially, a lack of preparedness and digital skills led to frustration, with 30% of faculty members struggling to adapt to online teaching platforms. However, as time passed, many noted an improved work- life balance, thanks to the option to teach remotely. Faculty training programs that were implemented six months into the transition resulted in a 20% boost in confidence among instructors using digital tools.

4.2.4 Departmental and student group adaptation to online learning from the study

To gain a deeper understanding of the digital transition, this section examines how various departments and student groups adjusted to online learning, providing examples of both successes and challenges.

4.2.4.1 The faculty of science and technology

The Faculty of Science and Technology transitioned to online learning with relative ease. Engineering students, for instance, adapted quickly thanks to their previous experience with digital tools and platforms for their coursework. The faculty introduced virtual laboratories, enabling students to conduct experiments online. This method preserved the hands-on aspect of their education, leading to a 15% increase in the completion rates of practical assignments compared to other faculties.

4.2.4.2 The faculty of education

On the other hand, the Faculty of Education encountered challenges, especially in adapting practical, hands-on teaching methods to a digital format. Teacher trainees, who usually participated in in-person classroom simulations, found it difficult to recreate this experience online. This group reported a 30% decline in engagement, particularly in activities that required interactive participation. However, by later integrating simulation software into the curriculum, this faculty experienced a 10% increase in engagement over time.

4.2.4.3 Vulnerable student groups

Students with disabilities faced additional hurdles during the transition, particularly due to the absence of accessible digital learning tools. For instance, students with visual impairments struggled to navigate the Learning Management System (LMS), resulting in a 25% decrease in engagement for this group. In response, UEW has since introduced accessibility features like screen readers, which have boosted engagement among students with disabilities by 15%.

4.2.5 Regional disparities in internet access

While general infrastructure issues have been widely discussed, it is crucial to emphasize the specific regional disparities in Internet access within Ghana that have significantly affected student engagement.

4.2.5.1 Rural vs. urban access

Students in rural areas encountered serious Internet connectivity problems, with 45% indicating that slow or unreliable Internet made it difficult for them to join live sessions and access course materials. In contrast, urban students experienced more dependable access, with only 15% reporting similar challenges. This gap was particularly noticeable in regions like the Upper East and Northern Ghana, where just 30% of students reported having adequate Internet access.

4.2.5.2 Infrastructure development

To tackle these regional disparities, UEW has been pushing for the expansion of Internet infrastructure in rural areas, working alongside government agencies and Internet service providers. Initial efforts have resulted in pilot projects in rural communities, providing subsidized Internet access to students. These initiatives have demonstrated a 10% increase in engagement among rural students during the early stages of implementation.

5 Discussions

The results of this study serve as substantial feedback on the digital learning approaches that UEW instituted to hammer out the challenges presented by COVID-19. On the one hand, moving to a digital format helped continue academic processes; on the other of course revealed many problems that need an instant solution aimed at improving educational quality and accessibility.

5.1 Objective I: assess students' engagement and academic performance student engagement metrics

The analysis of student engagement metrics reveals a clear disparity in how students interact with digital learning platforms. High engagement is characterized by active participation in online discussions, consistent attendance in live sessions, and high assignment completion rates. The data shows that institutions where these metrics are high generally achieve better academic outcomes. This correlation aligns with existing literature that suggests increased student engagement contributes to improved learning outcomes [48, 49].

5.1.1 Impact on academic performance

The positive relationship between student engagement and academic performance is evident from the significant differences in average grades and failure rates. Institutions with high engagement levels report an average grade increase of 10% and a decrease in failure rates by 12% compared to their lower engagement counterparts. This finding supports the notion that engaged students are more likely to succeed academically due to increased motivation and participation [50].

Moreover, lower engagement levels are associated with poorer academic performance, corroborating previous studies that link low engagement with higher dropout and failure rates [51]. The clear gradient in performance metrics suggests that engagement acts as a critical lever for enhancing student achievement.

5.1.2 Comprehensive implications

These findings emphasize the importance of fostering student engagement through strategies such as interactive content, regular feedback, and supportive learning environments. Institutions should focus on identifying barriers to engagement and addressing them to enhance overall academic performance.

5.2 Objective II: assess faculty preparedness and student outcomes faculty preparedness

The survey results reveal that a significant proportion of faculty members are either fully trained or partially trained in digital teaching methods. However, 25% remain untrained, which could impact their ability to deliver online instruction. This finding highlights a gap in faculty development that may hinder the effectiveness of digital learning environments [52].

5.2.1 Impact on student outcomes

The data shows a strong correlation between faculty preparedness and student outcomes. Institutions with fully trained faculty report higher average grades and greater student satisfaction compared to those with partially trained or untrained faculty. Specifically, institutions with fully trained faculty see a 12% increase in average grades and a 20% increase in student satisfaction.

This relationship underscores the critical role of faculty training in enhancing teaching effectiveness and, consequently, student performance [53]. Well-prepared faculty are better equipped to utilize digital tools effectively, deliver engaging content, and provide timely feedback, all of which contribute to improved student outcomes.

5.2.2 Implications for faculty development

To address the observed disparities, institutions should invest in comprehensive faculty training programs focused on digital pedagogy. Providing ongoing professional development and support can help bridge the gap between different levels of faculty preparedness, thereby improving overall educational quality and student satisfaction.

5.3 Objective III: predict student engagement based on infrastructure variables

5.3.1 Infrastructure variables

The analysis of infrastructure variables reveals that Internet connectivity, digital resource availability, and technical support significantly impact student engagement. Institutions with high-quality infrastructure in these areas tend to have higher engagement levels. This finding aligns with the conceptual framework proposed by the Technology Acceptance Model [54] which suggests that perceived ease of use and usefulness of technology affect user engagement and acceptance.

5.3.2 Machine learning analysis

The machine learning models used for predicting student engagement based on infrastructure variables provided valuable insights:

The findings of this study align with existing research that highlights the relationship between infrastructure quality and student engagement. Prior studies have also demonstrated that linear regression models effectively capture moderate relationships between learning environments and engagement levels [55]. However, some researchers, for example, [56, 57] found higher R2 values, suggesting that additional factors—such as teacher effectiveness or digital accessibility—may enhance predictive power.

The Decision Tree model in this study revealed key variables but suffered from overfitting, which is a known limitation in educational data modeling[58]. In contrast, some researchers have successfully mitigated this issue by incorporating pruning techniques or ensemble methods, resulting in more generalizable findings [59].

The Random Forest model, which showed the highest predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.78), is consistent with research by Smith et al. [60], who also found that ensemble methods outperform single-tree models in predicting student engagement [61]. Argue that psychological factors, such as motivation and self-efficacy, can sometimes have a stronger influence than infrastructure alone.

5.3.3 Feature importance

The analysis identified Internet connectivity as the most critical factor in predicting student engagement, followed by digital resources and technical support. This result highlights that reliable and fast Internet is fundamental to effective online learning, as it ensures seamless access to course materials and participation in interactive elements.

5.3.4 Predicted engagement levels

The predictions indicate that improving infrastructure quality could significantly increase student engagement. Institutions with high-quality infrastructure could see a 20% increase in engagement, while those with lower-quality infrastructure might not experience substantial changes without significant improvements.

5.3.5 Comprehensive implications

These results emphasize the need for institutions to prioritize infrastructure enhancements to boost student engagement. Investments in high-speed Internet, abundant digital resources, and responsive technical support are essential for creating conducive learning environments. Policymakers and educational administrators should consider these factors when designing and implementing digital learning strategies.

6 Conclusion and recommendations

The adaptation of the University of Education, Winneba, to online learning as a result of COVID-19 has given some insight into the challenges and prospects for digital education. The study found that although the institution was able to carry out its academic mandate, there were pronounced inequities in access and readiness, most notably among students originating from rural areas and faculty lacking digital competencies. Moreover, investments of this sort would be strategic in a more equitable and resilient approach to education.

In summary, taking the novel nature of the Covid-19 pandemic into consideration, making UEW move towards online learning was a justifiable response to unexpected times. Although the move enabled education to continue, it also unmasked huge problems of infrastructure as well as digital literacy and accessibility. This study recommends the implementation of (1) large-scale investment in digital infrastructure supporting online learning, (2), continuous training for staff to improve their teaching skills and support a more pedagogical use of tools—both being essential components; two other pillars aiming at inclusive policies allowing an equal access to these resources on-line by all students and regular evaluations performances updating initiatives that promote enjoyable education with tech-functional adjustments consistently.

Data availability

All data used for analysis in this manuscript is available from the corresponding author or first author upon reasonable request.

References

Aheto-Tsegah C. Education in Ghana–status and challenges. Common Educ Partnersh. 2011. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid3020023.

Adu-Agyem J, Osei-Poku P. Quality education in Ghana: the way forward. Int J Innov Res Dev. 2012;1(9):164–77.

Baafi RKA. School physical environment and student academic performance. Adv Phys Educ. 2020;10(02):121.

Mohammed AK, Kuyini AB. An evaluation of the Free Senior High School Policy in Ghana. Cambridge J Educ. 2020;51(2):1–30.

Dankyi JK, Nyieku IE. Hierarchical effect of psychosocial factors and job satisfaction on academic staff commitment to the university: the case of University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Open J Soc Sci. 2021;9(3):372–86.

Anlimachie MA, Avoada C. Socio-economic impact of closing the rural-urban gap in pre-tertiary education in Ghana: context and strategies. Int J Educ Dev. 2020;77: 102236.

Amewu S, Asante S, Pauw K, Thurlow J. The economic costs of COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa: insights from a simulation exercise for Ghana. Eur J Dev Res. 2020;32(5):1353–78.

Amoah C. Effective teaching and learning method: online versus face-to-face. In: Akinlolu M, Makua M, Ngubane N, editors. Online teaching and learning in higher education: issues and challenges in an African context. Springer: Cham; 2024. p. 107–27.

Maphalala MC, Ajani OA. The COVID-19 pandemic: Shifting from conventional classroom learning to online learning in South Africa’s higher education. Int J Innov Technol Soc Sci. 2023. https://doi.org/10.31435/rsglobal_ijitss/30062023/8002.

Chelliq I, Anoir L, Erradi M, Khaldi M. Transition from face-to-face to e-learning and pedagogical model. In: Eteokleous N, Ktoridou D, Kafa A, editors. Emerging trends and historical perspectives surrounding digital transformation in education: achieving open and blended learning environments. Hershey: IGI Global; 2023. p. 52–77.

Onyeaka H, Passaretti P, Miller-Friedmann J. Teaching in a pandemic: a comparative evaluation of online vs. face-to-face student outcome gains. Discov Educ. 2024;3(1):54.

Rutayisire T, de Dieu Iyakaremye J, Gace AD, Rutikanga JU, Leon N. Needs assessment for promoting transformational change towards accessibility in education and competence mobilization for e-learning at the University of Rwanda. 2024. https://doi.org/10.14507/MCF-eLi.I10.

Nherera C, Mukora FN. Digitalisation of higher education in Zimbabwe: a challenging necessity and emerging solutions. J Comp Int High Educ. 2024. https://doi.org/10.2674/jcihe.v16i2.6040.

Paschal MJ, Gougou SA-M, Kagendo NM. Shifting the balance: the status of e-learning in Sub-Saharan Africa in the age of global crisis. In: Chakraborty S, editor. Challenges of globalization and inclusivity in academic research. Hershey: IGI Global; 2024. p. 20–34.

Goh PSC, Blake D. E-readiness measurement tool: scale development and validation in a Malaysian higher educational context. Cogent Educ. 2021;8(1):1883829.

Mutula SM, Van Brakel P. An evaluation of e-readiness assessment tools with respect to information access: towards an integrated information rich tool. Int J Inf Manage. 2006;26(3):212–23.

Ghansah B, Andoh JS, Gbagonah P, Okogun-Odompley JN. The determinant of student satisfaction in academic and administrative services in private universities. In: Information Resources Management Association (Ed.) Research anthology on preparing school administrators to lead quality education programs: IGI Global: Hershey. 2021. pp. 1534–1551.

Ghansah B, Benuwa BB, Ansah EK, Ghansah NE, Magama C, Ocquaye ENN. Factors that influence students’ decision to choose a particular university: a conjoint analysis. Int J Eng Res Afr. 2016;27:147–57.

Sperber AD, et al. Worldwide prevalence and burden of functional gastrointestinal disorders, results of Rome Foundation global study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):99–114.

Hamburg I. COVID-19 as a catalyst for digital lifelong learning and reskilling. Adv Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.9734/air/2021/v22i130282.

Okine R, Okine Y, Agbemenu A. Engineering education online: our approach, challenges & opportunities (a case study of KNUST). In: Conference on M4D mobile communication technology for development. 2005. p. 14.

Adel A, Dayan J. Towards an intelligent blended system of learning activities model for New Zealand institutions: an investigative approach. Human Soc Sci Commun. 2021;8(1):1–14.

Wilson KN, Ghansah B, Ananga P, Oppong SO, Essibu WK, Essibu EK. Exploring the efficacy of computer games as a pedagogical tool for teaching and learning programming: a systematic review. Educ Inf Technol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13005-2.

Ibrahim NK, et al. Medical students’ acceptance and perceptions of e-learning during the Covid-19 closure time in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(1):17–23.

Martin A. Digital literacy and the “digital society.” Dig lit Conc Polic Pract. 2008;30(2008):151–76.

Aparicio M, Bacao F, Oliveira T. An e-learning theoretical framework. E Learn Theor Framew. 2016;1:292–307.

Jethro OO, Grace AM, Thomas AK. E-learning and its effects on teaching and learning in a global age. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci. 2012;2(1):203.

Kapila P. Rethinking education: An Overview of E-Learning in post covid-19 scenario. Int J Creat Res Thoughts. 2021;9(3):798–808.

White EPG et al., Approaches to leveraging digital higher education in Africa. In: Proceedings of the 6th ACM SIGCAS/SIGCHI conference on computing and sustainable societies. 2023. pp. 152–154.

Jakoet-Salie A, Ramalobe K. The digitalization of learning and teaching practices in higher education institutions during the Covid-19 pandemic. Teach Public Adm. 2023;41(1):59–71.

Fitria TN. Students’ problems in online learning: what happened to the students in English class during pandemic Covid-19? J Engl Lang Learn. 2023;7(1):334–45.

Ocloo EC, Coffie IS, Asigbe-Tsriku GRM, Tsagli SK. A qualitative study to understand the benefits and difficulties of virtual teaching and learning: the perspectives of students and faculty. Int J Qual Stud Educ. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2024.2388673.

Ajibo HT, Ene JC. Examining the prospect of online education as drivers of effective and uninterrupted university education in the post-COVID-19 era. J Appl Res High Educ. 2024;16(4):988–1000.

Akmad A. Academic resilience in the face of internet challenges: a narrative analysis of tertiary students’ experiences. J Int Perspect. 2024;2(8):551–63.

Pillay AM, Madzimure J. Analysis of online teaching and learning strategies and challenges in the COVID-19 era: lessons from South Africa. NETSOL New Trend Soc Lib Sci. 2023. https://doi.org/10.24819/netsol2023.3.

Ogegbo AA, Tijani F. Managing the shift to online: lecturers’ strategies during and beyond lockdown. Educ Res. 2023;65(1):24–39.

Ajamu GJ, et al. Online teaching sustainability and Strategies during the COVID-19 epidemic. In: Rosak-Szyrocka J, Żywiołek J, Nayyar A, Naved M, editors., et al., The role of sustainability and artificial intelligence in education improvement. Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton; 2024. p. 106–32.

Zhang R, Bi NC, Mercado T. Do zoom meetings really help? A comparative analysis of synchronous and asynchronous online learning during Covid-19 pandemic. J Comput Assist Learn. 2023;39(1):210–7.

Regnier J, Shafer E, Sobiesk E, Stave N, Haynes M. From crisis to opportunity: practices and technologies for a more effective post-COVID classroom. Educ Inf Technol. 2024;29(5):5981–6003.

Siregar KE. Increasing digital literacy in education: analysis of challenges and opportunities through literature study. Int J Multiling Educ Appl Linguist. 2024;1(2):10–25.

Getenet S, Cantle R, Redmond P, Albion P. Students’ digital technology attitude, literacy and self-efficacy and their effect on online learning engagement. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2024;21(1):3.

Luo Y, Han X, Zhang C. Prediction of learning outcomes with a machine learning algorithm based on online learning behavior data in blended courses. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2024;25(2):267–85.

Turnbull D, Chugh R, Luck J. Transitioning to e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: how have higher education institutions responded to the challenge? Educ Inf Technol. 2021;26(5):6401–19.

Symeonidis V, Francesconi D, Agostini E. The EU’s education policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a discourse and content analysis. CEPS J. 2021;11:89–115.

Singh J, Steele K, Singh L. Combining the best of online and face-to-face learning: hybrid and blended learning approach for COVID-19, post vaccine, & post-pandemic world. J Educ Technol Syst. 2021;50(2):140–71.

Kumar D. How emerging technologies are transforming education and research: trends opportunities, and challenges infinite horizons: exploring the unknown. Patna: CIRS Publication Patna India; 2023. p. 89–117.

Busetto L, Wick W, Gumbinger C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol Res Pract. 2020;2(1):14.

Kahu ER, Nelson K. Student engagement in the educational interface: understanding the mechanisms of student success. High Educ Res Dev. 2018;37(1):58–71.

Wong ZY, Liem GAD, Chan M, Datu JAD. Student engagement and its association with academic achievement and subjective well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Educ Psychol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000833.

Lynam S, Cachia M, Stock R. An evaluation of the factors that influence academic success as defined by engaged students. Educ Rev. 2024;76(3):586–604.

Woreta GT. Predictors of academic engagement of high school students: academic socialization and motivational beliefs. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1347163.

Phulpoto SAJ, Oad L, Imran M. Enhancing teacher performance in e-learning: addressing barriers and promoting sustainable education in public Universities of Pakistan. Pak Lang Human Rev. 2024;8(1):418–29.

Groenewald E, Kilag OK, Cabuenas MC, Camangyan J, Abapo JM, Abendan CF. The influence of principals’instructional leadership on the professional performance of teachers. Exc Int Mult discipl J Educ. 2023;1(6):433–43.

Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008.

Baragash RS, Al-Samarraie H. Blended learning: Investigating the influence of engagement in multiple learning delivery modes on students’ performance. Telemat Inform. 2018;35(7):2082–98.

Hazzam J, Wilkins S. The influences of lecturer charismatic leadership and technology use on student online engagement, learning performance, and satisfaction. Comput Educ. 2023;200: 104809.

Walas-Trębacz J, Krzyżak J, Herdan A, Setyohadi DB, Jeyanathan JS, Nair A. Social interactions and attitudes toward remote learning vs perceptions of its effectiveness in the view of education 4.0. TQM J. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-09-2024-0335.

Moslehi S, Rabiei N, Soltanian AR, Mamani M. Application of machine learning models based on decision trees in classifying the factors affecting mortality of COVID-19 patients in Hamadan, Iran. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022;22(1):192.

Rane N, Choudhary SP, Rane J. Ensemble deep learning and machine learning: applications, opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Stud Med Health Sci. 2024;1(2):18–41.

Smith PF, Ganesh S, Liu P. A comparison of random forest regression and multiple linear regression for prediction in neuroscience. J Neurosci Methods. 2013;220(1):85–91.

Zimmerman N, et al. A machine learning calibration model using random forests to improve sensor performance for lower-cost air quality monitoring. Atmosp Meas Tech. 2018;11(1):291–313.

Funding

This research was supported by the GOT project funded by the Erasmus + program (Project Number 101082794).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I am the sole author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The University of Cape Coast, Institutional Review Board (Ucc-Irb) approved this study for the GOT Erasmus + project. In addition, we confirm that all processes were executed in accordance with all applicable rules and guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghansah, B. From crisis to opportunity: the digital evolution of higher education in Africa amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Discov Educ 4, 122 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-025-00527-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-025-00527-1