Abstract

The European Union has navigated numerous complex and multifaceted crises in recent years, including Brexit, refugee challenges, and economic turmoil. The COVID-19 pandemic has added a global-scale event with significant implications, elevating public health protection as a central priority for the EU. This study aims to examine the personalization (stakeholders involved), impact, and digital engagement resulting from diverse communication strategies on Twitter during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign by key EU institutions. Employing a primarily quantitative approach, the research conducts a content analysis that categorizes both quantitative and qualitative elements to explore various variables and engagement indicators in the official accounts of the European Commission, European Parliament, and European Council. The findings suggest that, while the vaccination campaign saw a substantial volume of posts from these profiles, they fell short in engaging, mobilizing, and attracting audiences on Twitter, highlighting enduring challenges in EU message management and dissemination, as identified in previous studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and its subsequent global repercussions have presented a historic challenge for the European Union (EU). While previous transnational policies of EU institutions have been analyzed in light of various poly-crises, including Brexit, refugee matters, and economic concerns, the EU has, since March 2020, prioritized public health as the cornerstone of its actions (Greer and Ruitjer, 2020).

On December 21, 2020, Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, announced the provisional authorization granted by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the first vaccine, marking the commencement of the vaccination campaign across all Member States. As a result, on December 27 of the same year, the initial doses of the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine were administered throughout European territories (European Commission, 2021). Taking into account the importance of this extraordinary milestone and considering that it has been shown that personalization is one of the basic characteristics that actually condition the effectiveness of political and institutional communication campaigns (Van Aelst et al. 2012), there is a pressing need to assess the stakeholders involved in the transmission of the message. This evaluation takes place within a framework characterized by the documented challenges of this international organization in implementing various communication policies (Barisione and Michailidou, 2017, Caiani and Guerra, 2017).

Although in the last few years there has been a proliferation of studies that address the European Union’s strategies from the public health communication perspective (Maldonado et al. 2020, Durand et al. 2021), this study focuses on the personalization (stakeholders) and user engagement of the digital organizational communication strategies adopted by the EU’s main institutions (the European Commission, the European Parliament, and the European Council) through the utilization of X (Twitter), a social network now considered indispensable in the realm of political and organizational communication (Parmelee and Bichard, 2012, Álvarez Peralta et al. 2023).

To this end, a quantitative content analysis has been developed, employing both manual and computerized procedures for systematic data collection. This approach allows for the extraction of trends and usage patterns (Jiménez Alcarria and Tuñón, 2023). By doing so, the study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the various mechanisms employed by European supranational bodies to engage their audiences during one of the greatest challenges in contemporary world history.

Literature review

Online organizational communication strategies and digital engagement: X/Twitter

Andrade (2005) describes organizational communication as a set of techniques and activities that aim to develop a strategy to facilitate and streamline the flow of messages among members and between the organization and its various audiences.

In addition, research conducted by various authors on communication in the public sphere (Jackson and Lilleker, 2011, Parmelee and Bichard, 2012, Gainous and Wagner, 2014, Jivkova Semova et al. 2017) has traditionally focused on politics, voter mobilization and participation, electoral campaigns, or the construction of the public image of the institution in question (Holtz Bacha, 2004). Grunig et al. (2003) have highlighted that incorporating concepts like branding into the external communication plan of any public entity can yield significant benefits, as strategically coordinated communicative actions can generate a positive link with external audiences. From the perspective of public sector communication, authors such as Luoma-aho et al. (2019) have examined how political communication operates on a global scale. They highlight the various possibilities of multilevel governance models to more effectively use communication to enhance their roles as public and political organizations (Likely, 2019; Reinikainen and Valentini, 2023). The proliferation of social networks, with their diverse characteristics and attributes, as well as their growing popularity, has made them novel and influential platforms in relational dynamics between senders and receivers (Duggan, 2015, Sloan and Quan Haase, 2017, Steward, 2017). The advent of social networks and their rapid development has made them a key component of organizational communication strategies, particularly those aimed at engaging younger audiences and bridging the psychological and geographical gap that separates them from political institutions (Gleason, 2018).

While Facebook remains the largest online network globally in terms of registered users (Duggan, 2015, Gurevich, 2016), X (formerly Twitter) stands out as the predominant social network for political organizations’ communication strategies and scientific studies in the social sciences field (Steward, 2017, Stier et al. 2018, Jiménez Alcarria and Tuñón, 2023). Research indicates that Twitter’s increasing presence in citizens’ daily agendas necessitates public institutions, such as those of the EU, to maintain constant communication and updates, as digital interactions significantly influence offline organizational behaviour and vice versa (Halpern et al. 2017, Conrad and Oleart, 2020, Hagemann and Abramova, 2023). Recent studies such as the one conducted by Silva and Proksch (2022) highlight the suitability of X/Twitter for the personalization of the institutional and political messages, as well as its use as the main channel for digital political communication.

In this sense, the concept of digital engagement has gone through multiple definitions, depending on the type of approach from different areas of study. There are even authors who have recently stated 'that it is still in the process of being refined' (Wolter et al. 2017: 9). The one that best fits the approach introduced in this research is the one that relates this term to the use of digital tools and techniques to bring about the meeting, listening and mobilisation of a community of users around a given issue (Vaccari, 2017). The materialisation of this concept in social networks occurs through behaviours of different intensity, ranging from simply reading or viewing the content (Paine, 2011), to leaving a 'like', a comment, or sharing/quoting/retweeting the publication (Barger and Labrecque, 2013). Likewise, in the field of journalism and political communication, it has been used of 'shareworthiness', which analyzes posts widely shared by users in social networks from the point of view of the characteristics that cause these posts to be shared on a large scale, as well as the users’ motivations that drive that sharing process (Trilling et al. 2017, Wischnewski et al. 2021). In this respect, Salgado and Bobba (2019) carried out a content analysis comparing the coverage of a series of events in different countries in order to evaluate the differences in interaction and engagement among Facebook users. While noting that 'the specific features of news content only slightly affected the levels of liking and sharing', it is interesting to note the evidence that negativity or personalization promotes the proliferation of comments among the Facebook community. Also, from the point of view of the type of comments made by users to news web articles or comments by other users on those same articles, Ziegele et al. (2018) highlight that news factors and comment characteristics increase participants’ willingness to comment through cognitive and affective involvement. Cognitive involvement reduces the likelihood of participants writing discourteous comments, whereas affective involvement increases it.

Among the positive effects that early engagement studies began to detect was the generalisation of the term viewertariat to refer to 'users who interpret, comment and discuss on Twitter what they are watching in real time, usually via television' (Anstead and O’Loughlin, 2010), as well as the emergence of certain authoritative political voices (known as ‘celebrities’/stakeholders) capable of influencing public opinion (Ampofo et al. 2011).

Furthermore, it is important to consider that existing empirical studies, such as Nulty et al. (2016) on the 2014 European Parliament elections, indicate that the level of interaction and conversational exchange between the EU institutions and their audiences is not occurring as effectively as desired. Similarly, research conducted by Graham et al. (2016) suggests that genuine interaction between political organizations and the user community, where the impact of their messages is felt, is not consistently evident in all campaigns or communication events.

European transnational communication

Drawing on the foundational principles of institutional communication within social media, this study aims to extend this conceptual framework to the supranational communication efforts undertaken by EU institutions.

Traditionally, the academic disciplines of comparative politics, international relations or political communication have not been concerned with the systematic analysis of transnational perspectives linked to the communication strategies of European political organizations (Tuñón and Carral, 2019:1222). According with Tuñon and Carral's perspectives, the absence until recent years of research on European communication from the aforementioned fields is closely linked to the approaches and methodologies of analysis. That is why, as suggested by Graber (2003) or proposed by Canel and Sanders (2012: 93), it is beneficial to study institutional communication from different research strategies within public communication. Consequently, this research aligns with other studies that seek to address this theoretical gap by adopting diverse frameworks from different perspectives in social sciences (Valentini, 2006, Brüggemann and Wessler, 2014, Rivas de Roca, 2020, Tuñón and Catalán, 2020). The aim is to adopt a multidisciplinary approach, drawing on various theoretical frameworks related to the application of milestone analysis to European communication (Graber, 2003; Gower, 2006).

Numerous authors have criticized the EU’s communication policy in light of recent 'poly-crises,' such as Brexit, refugee matters, and eurozone instability, which have significantly impacted the future of international relations and intra-EU relations (Papagianneas, 2017). This critique has led to extensive discussions on the operational efficacy of European communication and its shortcomings regarding European integration (De Wilde et al. 2014, Barisione and Michailidou, 2017, Caiani and Guerra, 2017). Numerous studies have analyzed the communication failures of the EU concerning traditional media (Thiel, 2008; Statham, 2016), such as the lack of European topics among the main news disseminated in mass media (Van Noije, 2010; Touri and Rogers, 2013) or the advantages of television for creating an absent common pan European public space (Kaitatzi Whitlock, 2007). However, while social media has proven to be a fertile ground for analyzing new forms of political communication (Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan, 2013), the literature focused on analyzing European institutional communication through these channels is significantly smaller (Nulty et al. 2016). Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by including the variables of personalization and engagement, which will allow for measuring the effectiveness and potential overcoming of the EU’s main communication failures during a crucial event such as the first vaccination campaign to address the pandemic.

Most of the cited studies developed on this issue underline the fact that the failure of the EU’s institutional communication underscores the necessity for a comprehensive reformulation of European political communication, emphasizing issues such as the creation of a European public sphere, identity crisis, multilingualism-induced fragmentation, the challenge posed by Euromyths (now referred to as 'fake news'), grassroots communication, and the application of European branding (Clark, 2014). They argue that the structural deficiencies in European political communication are rooted in the EU’s construction and governance, as well as the nature of the community it has fostered, characterized by a significant lack of identification with European affairs.

In addition to these factors, theoretical expectations regarding the factors contributing to the lack of homogenization of the European message include inter-institutional competition, a lack of hybridization in terms of the distribution of information on European public policies, and a multitude of speakers conveying divergent messages, all without a common communicative strategy (Papagianneas, 2017, Rauh et al. 2020, Jiménez Alcarria and Tuñón, 2023). Recent research has also uncovered another failure of European communication: the generation, distribution, and management of a purportedly European message by the EU primarily involves the political-institutional elites surrounding it, while excluding the participation of various stakeholders in European society, such as different civil society groups, journalists, or the media themselves (Meyer, 2009, Fazekas et al. 2020, Rauh, 2022).

In this regard, the focus should not only be on the impact, reception, and engagement of European messages among audiences but also on the stakeholders involved in publications as voices of the messages and the personalization of their public relations. It is crucial to note that the personalization of messages is a fundamental characteristic of the content generated on X/Twitter profiles (Van Aelst et al. 2012; Vergeer and Hermans, 2013; Vergeer et al. 2013). Emphasizing that the personalization remains a constant variable in transnational European communication, it is defined as a discourse focused on the individuals involved, highlighting their intrinsic qualities over the content of the messages or the underlying ideology; essentially, a predominance of form over content (López Meri and Casero Ripollés, 2017). An updated and integrative definition of personalization, which encompasses the nuances mentioned by previous authors and serves as a reference for this study, is provided by Langer and Sagarzazu (2018). This perspective analyzes personalization as the increasing centrality and autonomy of individual politicians over collective institutions (parties, cabinets, and parliaments) over time.

Traditionally, mass media like television have promoted the personalization of political and institutional discourse by simplifying messages through audiovisual strategies to maximize their reach among potential audiences (Blumler and Kavanagh, 1999; McAllister, 2007). Following this argument, McAllister (2007) introduces the concept of 'political priming' to describe the process by which political leaders at the forefront of institutions are evaluated by voters based on a small sample of actions in the most covered issues in the media, constantly linked to the leader’s personality. Although the causes of the personalization of politics are complex and multifactorial, international trends have shown a clear dominance and uniformity in the use of these strategies for decades (Schudson, 1995).

Social media has enabled new forms of personalization in the political and institutional realms, particularly X (formerly Twitter) due to its ability to impact audiences in an environment that privileges proximity and closeness with the user (López Meri et al. 2017). Van Aelst et al. (2012) highlight individualization and privacy as two main dimensions of personalization. Bouza and Tuñon (2018) demonstrate how these variables have been fundamental to the political success of French President Emmanuel Macron, from strategically planned communication centred around the candidate to the projection of his personal side.

However, this personalization should not be confined to the communication of political leaders with their local audiences, but also within the European Union. In her detailed study on the personalization of European politics from a transnational perspective, Gattermann (2022) suggests that to properly understand the recent evolution and implications of personalization in European communication, a global approach is necessary. This includes examining the personalization of politics over time and across various internal political contexts within the EU. To this end, four categories of analysis are defined: institutional personalization, personalization of politician behaviour, media personalization, and personalization in citizen attitudes and behaviour (Balmas et al. 2014; Gattermann, 2020; Hamřík and Kaniok, 2022).

In this context, the case study of the French president and his speech before the European Parliament highlighted the importance of personalization in transnational political communication strategies and its potential for conveying the European message and achieving a decisive position as a transnational political actor (Bouza and Oleart, 2022). This personalization enables effective communication in fragmented public spaces (Pedersen and Rahat, 2021). Therefore, this study aims to complement the still scarce literature on personalization in European institutional communication, using the 2021 COVID-19 vaccination campaign as the main event. As demonstrated, measuring the impact and effectiveness of these communication strategies requires considering the various actors involved in the different personalization efforts undertaken during this campaign.

Effective European communication is not a trivial matter. Just as public institutions belonging to the Member States’ governments have an obligation to convey information related to European affairs to citizens, the EU itself must respond to their actions in a similar manner, using the various online and offline platforms available for this purpose (Scherpereel et al. 2016). Despite the challenges highlighted by scholars, which place the EU at a crossroads in terms of organizational communication, the imperative to open up its communication policy to emerging technological methodologies presents a unique opportunity to modernize, segment, and unify the message, appropriately redirecting it based on the characteristics of the new audiences (Hänska and Bauchowitz, 2019).

Research objectives and hypotheses

The primary objective of this research is to examine the stakeholders, impact, and reception of digital organizational communication strategies employed by the primary EU institutions on X/Twitter to engage European national public opinions during the crucial months of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign.

This general objective is then broken down into the subsequent specific objectives:

-

To define the stakeholders involved in the broadcasting of messages through the social network X/Twitter, in order to assess the level of personalisation in the discursive construction of the publications.

-

To quantify the impact of these messages on the X/Twitter community and to contrast the patterns of digital engagement in order to determine the effectiveness of the strategy deployed, as well as to identify the types of audience towards which the publications are focused.

In line with the objectives outlined for this study, the following working hypotheses are formulated:

-

Hypothesis 1: In reference to the stakeholders issuing the messages on vaccination, despite mostly addressing the general public, the main institutional profiles of the EU have eminently involved the political, institutional elites and surrounding stakeholders themselves, with a low degree of personalisation in the construction of their publications.

-

Hypothesis 2: The publications on the vaccination campaign, have involved a low volume of interactions and engagement, within the European community of users likely to be impacted by the content of these profiles.

Materials and methods

To ensure a robust analysis and to test the various hypotheses put forward, this study primarily adopts quantitative methodological approaches. The central method employed is content analysis due to its capacity to systematically discern the manifest or latent content of texts to make inferences about the issuer and possible effects on audiences. Its reliability and reproducibility have been affirmed by several authors, making it a predominant technique in social sciences studies (Wimmer and Dominick, 1996).

After an initial analysis and preliminary reading of digital organizational communication content published by various European institutional profiles, purposive sampling techniques were utilized to narrow down the sample of publications to be coded. The selection process was guided by two priority criteria: the number of followers and the profile’s significance within the European institutional network’s organizational chart. As a result, the analysis of publications was limited to the profiles of the European Commission (@EU_Commission; 1.5 million followers), the European Parliament (@Europarl_EN; 767,600 followers), and the European Council (@EUCouncil; 596,000 followers) during the first three months of the vaccination campaign: from December 21st, 2020, to March 27th, 2021. A total of 1014 tweets (n = 1014) were counted during the 97-day period covered by the aforementioned timeframe. It should be noted that the coding was only conducted for publications in English, as the objectives of this study are linked to the evaluation of indicators present in the transnational public space.

This timeframe was chosen due to several factors: on December 21st, 2020, the EMA granted provisional authorization to the first BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine, followed by a speech by the President of the Commission, Ursula von der Leyen. Therefore, it is significant to consider the week preceding the start of vaccination in terms of organizational communication, as its mechanisms were activated from this initial public intervention. Additionally, the first doses were administered in the Member States on December 27th. Furthermore, the three consecutive months cover the two key milestones of this campaign: the approval of the primary vaccines then in circulation (BioNTech/Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson-Janssen, Oxford-Astrazeneca, and Moderna) and the two crises with the most institutional resonance: the EU’s opacity in export contracts to third countries and the adverse effects caused by AstraZeneca.

Once the sample of publications was delimited, the coding protocol defined the different categories of analysis, incorporating qualitative and quantitative indicators corresponding to the various theoretical expectations and hypotheses to be tested. This protocol was developed from the available material provided by previous studies in the field of organizational and/or political communication (particularly Pfetsch et al. 2010, Bouza and Tuñón, 2018, Bright et al. 2019, Jiménez Alcarria and Tuñón, 2023). This allowed for the identification and refinement of categories related to the stakeholders involved as issuers and target audiences (to which specific group the tweets appealed). These categories were examined and subjected to a detailed evaluation by experts and researchers in organizational and digital communication, using a Likert scale to assess their relevance, with an average score of 4 out of a possible 5 points. To calculate intercoder reliability, the Cohen’s Kappa statistical measure was applied (Oleinik et al. 2014). The sample was coded independently by the two researchers who conducted the study. This coefficient was calculated for each of the two variables, which are mutually exclusive: stakeholders and target audiences. Both variables yielded a similar result of K = 0.7.

Stakeholders mentioned in the body of the post itself, either through a specific mention of another profile (@), or simply by referring to the instance in question as an actor/stakeholder involved in a given message, were counted to take into account the level of personalization of the tweets. This is the only variable that caused disagreement among coders on some occasions was the stakeholders involved, hence the coefficient presented. On some posts, the way the tweet was presented caused interference when categorizing them as tweets cited or with mention. As the categories have been developed and their effectiveness proven in previous research (in addition to being subjected to expert analysis and using a Likert scale), no distortions were considered relevant to the reliability of the content analysis and these cases of disagreement were corrected prior to the analysis of results Table 1.

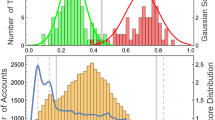

In order to compile the publications and extract the information corresponding to the different variables, different software programmes specialised in handling large amounts of data were used (X/Twitter Web Analytics, API, SPSS). The information related to X/Twitter engagement has been obtained from the quantification of 'likes', retweets or 'shares' and comments, as these are indicators of great interest, widely used to account for the degree and volume of engagement shown by users (Wolter et al. 2017). The categories have been quantified through the use of pro-rata intervals, with the ultimate aim of facilitating the extraction and systematisation of significant results, following the guidelines established by previous engagement studies (Giglietto and Selva, 2014, Vaccari, 2017).

With the ultimate aim of correcting the distortion of the absolute data caused by the imbalance in terms of the followers from the different accounts, the raw metrics have been corrected by calculating the engagement rate. Several models legitimised in the academic community have been developed to calculate this rate, which is essential to relativise the data and contextualise them. Due to the nature of this analysis and with the aim of reducing the deviations caused by the divergent number of followers or scope between the different profiles, we chose to use the formula established by Niciporuc (2014). This calculation divides the total interactions by the number of followers of the account. The number of followers represents one of the main elements for defining the potential reach of an X/Twitter account; in other words, the users likely to be impacted by an organic publication, without taking into account promoted publications (paid advertising). This rate has been used by other, more recent publications, which continue to report its validity and operability to measure engagement during a given period (Pulido Polo et al. 2021).

In this case, however, the aggregate rate has not been useful for comparative analysis of the engagement of publications framed within the vaccination campaign with respect to the rest (since under this formula it is always lower, as the number of 'likes', retweets and comments filtering only these messages will also be lower). Therefore, in addition to the overall engagement rates, the specific calculation of the individual engagement rates for each publication has been carried out in order to obtain the overall average engagement rate per publication. This operation allows a comparative evaluation to be made between the aggregate average rate per publication and that corresponding to the fraction of the sample framed thematically in this campaign, in order to compare whether the publications on vaccination are above or below the general average. As a complement to the above, the different hashtags used by these profiles have been systematised, as these tags are fundamental elements for structuring the conversation and connecting the issuing profiles with their user communities (Jivkova Semova et al. 2017).

With reference to the establishment of the categories for the target audiences (group to which a given post is specifically addressed or appeals as a priority), we consider the different characteristics of the diverse user profiles that follow these X/Twitter accounts. The specific divisions are inspired by recent theoretical postulates (Tuñón and Catalán, 2020), which have established a series of predominant groups towards which European institutions focus Table 2.

Results

To enable analysis and subsequent comparison of different indicators, the results pertaining to the specific sample fraction of the vaccination campaign are presented in relation to the overall percentages of the complete sample for each institution.

European Commission (@EU_Commission)

Within the framework of the vaccination campaign, there is a greater diversification of profiles with regard to the stakeholders involved as issuers, compared to the general distribution. 50.94% of the tweets (81) grouped under this theme do not contain mentions to any instance, while 17.61% (28 tweets) involve other EU institutions. 11.32% and 10.06% of the messages correspond to mentions of stakeholders with a scientific/research profile (18 tweets) and public officials (16 tweets), respectively. These are followed by quotations of EU institutions (9 tweets/5.66% of the total number of publications referring to the vaccination campaign), as well as mentions of civil society stakeholders (4 tweets/2.52%). The percentage of own stakeholders decreases slightly in relation to the overall average, with 88.35% of the aggregated publications corresponding to own sources, while in this case, the average figure drops to 84.72%.

In the vaccination fraction of the sample, the target audiences have not differed significantly from the overall aggregate statistical distribution. Nevertheless, certain indicators are worth mentioning. The percentage of publications addressed to the general public (139 tweets/87.42%) and to specific Member States (7 tweets/4.40%) has increased, at the cost of a significant reduction of eight percentage points in those messages addressed to European youth (3 tweets/1.89%). On the other hand, the percentage of target audiences whose audiences are scientific or specialised remains the same (7 tweets/4.40%) Table 3.

The publications in this thematic area have a higher engagement rate per publication than the general average (0.0276%). In both cases, the result remains very low, below 1%. As with the general distribution, more than half of the publications corresponding to this portion of the sample (86 tweets/54.09%) are between 26 and 100 shares. In any case, the number of tweets involving between 101 and 200 retweets (41/25.79%) increases compared to the overall data, as well as those involving between 301 and 400 (4 tweets/2.52%) and more than 500 (5 tweets/3.14%) shares or retweets. 'Likes' are primarily concentrated in the fourth band, with 62 tweets (38.99%) about the campaign. Additionally, 10.69% (17 tweets) reached the maximum range, garnering over 500 likes. Notably, comments show an even greater concentration, with 45.91% (73 tweets) receiving between 6 and 25 comments, and 38.99% (62 tweets) falling within the range of 26 to 100 comments. Notably, no publication on the vaccination campaign has garnered more than 300 comments. Additionally, all posts in this category show interactions across all three evaluated indicators (comments, retweets, and 'likes'), with every message exhibiting some level of engagement.

European Parliament (@Europarl_EN)

Continuing the analysis with the typology of stakeholders involved in the body of the tweets as senders of the messages on the vaccination campaign, 81.82% of publications (27 tweets) framed under this thematic area do not contain any mention, while 4 tweets (12.12%) involve EU political leaders. On all 4 occasions, the President of the European Commission is included as a stakeholder, recovering extracts from her appearance on February 10th, 2021, the main focus of which was on the level of achievement of the vaccination strategy. The 'Quote Tweet' formula is used only once, in this case, to quote another publication of the European Parliament itself, on the degree of implementation of vaccines in the Member States. In any case, 100% of the issuing actors are themselves, without mentioning or giving a voice to elements of civil society or other bodies.

The analysis reveals that the European Parliament’s publications on vaccination target an even more concentrated audience type compared to the general distribution. Publications aimed at the general European public dominate, accounting for 31 tweets (93.94% of the sample in this thematic area). The remaining two tweets (6.06%) address the campaign by appealing directly to inter-institutional competence, urging all EU supranational bodies to adopt a unified approach to the vaccination strategy Table 4.

Finally, in the data referring to engagement and volume of interactions, the tweets on the vaccination campaign show a similar distribution to the general one, as the total number of publications is concentrated in the first brackets of interactions. However, the average engagement rate per post calculated for this group of messages is slightly lower than the overall average (0.0113%). All the publications in this thematic area receive user engagement through retweets and 'likes,' though with varying degrees of intensity. Retweets are distributed between the second and third intervals: 22 tweets (66.67%) on vaccination have between 6 and 25 retweets, while 11 publications (33.33%) fall between 26 and 100 shares. The volume of likes is notably higher than the overall totals. While 80.25% of the aggregate publications are between 26 and 100 interactions, a higher 87.88% of the tweets in this campaign (29 tweets) fall within this range. Additionally, 6.06% (2 tweets) receive between 6 and 25 likes, and another 6.06% (2 tweets) garner between 101 and 200 likes. This data underscores the higher level of user engagement with tweets related to the vaccination campaign. Much lower is the number of active interventions by the user community commenting on posts, with the majority of posts on the topic (24 tweets/72.73%) involving between 6 and 25 comments. Behind are those that provoke between 1 and 5 comments (5 tweets/15.15%), those between 26 and 100 (2 tweets/6.06%) and those with no comments at all (2 tweets/6.06%). Similarly, it should be noted that the only two European Parliament publications that do not involve comments from users are located within the vaccination campaign.

European Council (@EUCouncil)

The stakeholders involved in the broadcasting of the messages that make up the publications on vaccination are more concentrated compared to the general distribution. A total of 93.33% are own stakeholders, slightly increasing the 89.67% corresponding to the overall average of aggregated publications. Some 70% of tweets (21 posts) contain no mention at all. These are followed by those that incorporate other EU institutions as issuing actors (4 tweets/13.33%). Marginally, scientists and other actors are involved (both with only one tweet and 3.33%), with no publications involving associations or members of civil society. The profile uses the 'Quote Tweet' formula in three messages (10%). On all three occasions, the EMA is mentioned, on January 8th, March 19th and 24th 2021, for the purpose of promoting online meetings designed for informative aims, to report on the successive reviews of the safety protocols applied to vaccines authorised in the EU and to dispel, to some extent (during the last two meetings), the doubts raised about the adverse effects produced by the AstraZeneca vaccine.

The target audiences are concentrated in a specific typology (always within the sample corresponding to the area of the vaccination campaign): the general public is the main target of most of the posts (25 tweets/83.33%), well ahead of those that seek to impact on European youth (3 tweets/10%), on a specialised audience (1 tweet/3.33%), or on other types of audiences (1 tweet/3.33%) Table 5.

On the other hand, the average engagement rate per publication corresponding to those tweets that belong to the thematic area of the vaccination campaign has remained reasonably stable with respect to the general average (0.0152%), discreetly increasing the percentage to 0.0242%. With reference to the rest of the indicators, 4 of the publications dealing with this topic do not involve any retweet, and most of them are concentrated in the first three intervals, with 2, 10 and 12 tweets, respectively (representing a percentage of 6.67, 33.33 and 40% of the total corresponding to this topic). Therefore, a majority percentage of the posts (73.33%) have between 6 and 100 retweets. The remaining two posts, located in the fourth (101–200) and fifth (201–300) range of shares, relate to the specific milestone of the EMA authorisation issued for the Moderna vaccine in January 2021. According to the number of 'likes', posts on the topic are mainly grouped in the third range, between 26 and 100 likes (10 tweets/33.33%), and in the fourth, between 101 and 200 likes (9 tweets/30%). Between 1 and 25 likes there are 6 publications, 3 in each of the first two ranges.

Despite the fact that the number of 'likes' is much higher than the number of shares, only two publications about the campaign are above the fifth range, one with 351 likes and the other with 401. Both correspond, as with the retweets, to the favourable opinion of the EMA on the authorisation of the Moderna vaccine. In total, only 2 posts did not get any 'likes', a very low percentage compared to the total number of messages related to vaccination (6.66%).

Finally, the number of comments is significantly lower than the number of 'Likes' and retweets. There are 5 tweets (16.66% of the total for this thematic category) that did not elicit any type of response from users, while the majority fall into the first two ranges: 10 tweets (33.33%) elicited between 1 and 5 comments and 12 tweets elicited between 6 and 25 (40%). Only 10% (3 tweets) elicited between 26 and 100 responses. It should be emphasised that of the 9 messages that did not elicit any comments, 5 were posts about vaccination.

Discussion

The primary focus of this study is to compare and contrast the various hypotheses put forward, while emphasizing the key findings of the current research: the level of interactions and engagement from the audiences remains notably low across all the accounts analyzed. This underlines the conclusions drawn in recent studies by De Wilde et al. (2014), Clark (2014), and Papagianneas (2017), which underscore the significant challenges the EU faces in terms of engaging its own citizens.

Firstly, Hypothesis 1 (with reference to the stakeholders issuing messages about the vaccination process, despite being mostly addressed to the general public, the EU’s main institutional profiles have eminently involved the political and institutional elites and surrounding stakeholders, with a low degree of personalisation in the construction of the messages) is confirmed in view of the results presented. Although a majority of the publications on the vaccination campaign are addressed to European citizens (84.72%/93.94%/83.34% respectively for the European Commission, the European Parliament and the European Council), this does not correspond, in any case, to that of the stakeholders involved in the broadcasting of the messages. The European institutions themselves maintain a clear hegemony in the three accounts in the publications that deal with the aforementioned campaign (87.42%/100%/93.33%). In this sense, the degree of personalisation and individualisation in the discursive construction of the tweets is equally low, especially given that this is a characteristic of X/Twitter that to a certain extent guarantees the success of the strategies and an effective approach to citizens (Vergeer et al. 2013). Furthermore, the personalisation of the message is achieved through the mention of institutional actors, and the personalities most frequently mentioned in the European Commission and the European Parliament are the different EU leaders, albeit with minimal percentages (10.06%/12.12%, with respect to the total number of publications on the vaccination campaign). In the case of the European Council, it is only (marginally) personalised to scientists and other stakeholders (6.66%). Following the categories established by Gattermann (2022) to analyze the personalization of politics in the European Union—namely, institutional personalization, personalization of politician behaviour, media personalization, and personalization in citizen attitudes and behaviour—it can be concluded that the communication strategies do not stand out from any of these perspectives.

In short, as the conclusions of Hänska and Bauchowitz (2019) and Šimunjak and Caliandro (2020) point out, although X/Twitter is postulated as a possible solution to the structural problems of European organisational communication, participation in the broadcasting of messages by actors outside the political-institutional elites surrounding these institutions is practically non-existent. It should also be contextualised, on the other hand, that the high degree of use of this social network by the profiles studied reflects a platformisation in European communication, defined as the growing dominance of digital platforms in shaping public discourse and access to information, which has profound implications for freedom of expression and how that discourse is constructed (Smyrnaios and Baisnée, 2023).

One of the traditional shortcomings detected in the transmission of the European message is therefore verified, as it is distributed in a single direction, in a self-referential manner and without involving other types of stakeholders, such as civil society or the media. The low percentage of messages about the vaccination campaign designed specifically for European youth (1.89%/0%/10%) is also worrying, as one of the opportunities of X/Twitter lies in its ability to reduce psychological and geographical distances with younger audiences and to effectively interact with them (Gleason, 2018). With regard to the limited degree of personalisation of messages, the recent research published by Rivas de Roca (2020) and Belluati (2021) on EU transnational communication on Twitter also highlights among its main conclusions the low degree of personalisation of EU policy, with the predominance of the mere dissemination of proposals.

For the discussion of the second hypothesis, the indicators corresponding to engagement rates will be used, since given the unequal number of followers of the three profiles, any other absolute data may lead to misunderstandings about these variables. In any case, the calculations performed allow us to validate Hypothesis 2 (the publications on the vaccination campaign, like the rest of the sample, have involved a low volume of interactions and engagement), as well as to reinforce the studies published by authors such as Nulty et al. (2016) and Fazekas et al. (2020), which demonstrate with empirical evidence, the fact that between the EU institutions and their X/Twitter audiences there is no significant exchange of interactions. The three average engagement rates per post that aggregate all the messages issued under this thematic area do not differ greatly from the overall average per post corresponding to the aggregate totals of the profiles. In the case of the European Commission and the European Council, the rate per post on vaccination is slightly higher than the general average for the three-monthly periods (0.0276%/0.0242%, respectively). That of the Parliament, on the other hand, is lower than the overall engagement rate per publication (0.0113%).

In any case, all of them are at very low percentages, and must therefore be considered deficient in terms of having a real impact on the target audiences. The overall rates for each institution (14.62%/5.15%/2.39%, continuing the order of appearance of the previous paragraph) makes possible to affirm that none of the three accounts generate a considerable volume of interactions from users, which is why these institutional profiles have not had a significant impact on X/Twitter. However, none of these figures can be compared with the calculation made to establish a comparative measure of engagement corresponding to the publications linked to the vaccination campaign, as in this case the average rate per post has been used as it is considered more appropriate and relevant to establish a correct comparison between this thematic category and the general level of engagement. This is also taking into account the abundant use of hashtags (#) to promote their visibility on the social network and encourage interactions. While the European Parliament does not use hashtags in its communication strategies focused on the vaccination campaign, both the Commission and the European Council use them in a majority way (89.93%/80% of the total number of publications on this topic), without detecting a volume of engagement that differs significantly from the rest. In this sense, the analysis of the different tags used allows us to reinforce the thesis formulated by Bouza and Tuñón (2018), as once again the profusion of excessively descriptive or institutional hashtags undermines and (to a certain extent) prevents the effective intervention of these institutions in the process of creating their own leading frames on European affairs.

In summary, this study has led to the conclusion that the strategies of the main EU institutions have not succeeded in significantly impacting, involving, and mobilizing European citizens to create a favourable framework on this issue. This is evident from the limited engagement and minimal level of personalization that predominantly involves the political-institutional elites of each institution. The results undeniably indicate that many of the traditional shortcomings in managing, broadcasting, and disseminating the European message, as described by various authors, persist.

However, the hypothesis testing in this study was subject to certain limitations. This research aimed to analyze stakeholders, target audiences, and engagement on X/Twitter based on a campaign that was still ongoing at the end of the study. Therefore, the results may be influenced, and their validity may be limited by strategic modifications that may have occurred during subsequent periods. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that during the process of narrowing down the sample (in the first phase of pre-analysis), superficial observation revealed that publication trends during April and May 2021 continued the patterns found in the months ultimately selected, with no major events of significant resonance that altered the strategic digital communication implemented by the EU for this campaign. Although it exceeds the specific objectives of the present research, future works aim to expand the scope by selecting a bigger sample (X profiles of European leaders or organizations such as the EMA) and the periods covered, in order to trace the evolution of the patterns detected in this initial approach.

Furthermore, an additional limitation and potential future complementary research direction will aim to establish a relevant comparison of these data with those obtained from the profiles of the different offices corresponding to these institutions in the various Member States (Stier et al. 2021). This will allow for an analysis of whether these shortcomings persist in these profiles or if different, segmented national discourses and strategies have been developed concerning the communication of the vaccination campaign. Another way to complement the research performed would be to carry out a comparative analysis with the same variables using other social media platform, such as Facebook. In this way, it would be possible to check whether it is possible to establish a generalisability between the different results obtained.

Data availability

The database of this research is public and was extracted from the referred Twitter accounts.

References

Álvarez Peralta M, Rojas Andrés R, Diefenbacher S (2023) Meta-analysis of political communication research on Twitter: methodological trends. Cogent Soc Sci 9(1):2209371. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2209371

Ampofo L, Anstead N, O’Loughlin B (2011) Trust, confidence, and credibility. Inf Commun Soc 14(6):850–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.587882

Andrade H (2005) Comunicación organizacional interna: proceso, disciplina y técnica. Netbiblo, Madrid

Anstead N, O’Loughlin B (2010) Emerging viewertariat: explaining Twitter responses to Nick Griffin’s appearance on BBC Question time. PSI working paper series 1. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/30032

Balmas M, Rahat G, Sheafer T, Shenhav SR (2014) Two routes to personalized politics: centralized and decentralized personalization. Part Politics 20(1):37–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068811436037

Barger VA, Labrecque L (2013) An integrated marketing communications perspective on social media metrics. Int. J. Integr. Mark. Commun. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2280132

Barisione M, Michailidou A (eds) (2017) Social media and European politics: rethinking power and legitimacy in the digital era. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Belluati M (2021) The European Institutions and their communication deficits. In: Newell JL (ed) Europe and the Left. Challenges to Democracy in the 21st Century. Palgrave Macmillan, London, p 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54541-3_4

Blumler JG, Kavanagh D (1999) The third age of political communication: Influences and features. Pol Com 16(3):209–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/105846099198596

Bouza L, Tuñón J (2018) The personalization, circulation, impact and reception in Twitter of Macron’s 17/04/18 speech to the European Parliament. Profesional de la Inf ón 27(6):1239–1247. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.nov.07

Bouza L, Oleart A (2022) Make Europe Great Again: The Politicising Pro-European Narrative of Emmanuel Macron in France. In: Haapala T, Oleart A (eds) Tracing the Politicisation of the EU. Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82700-7_12

Bright J, Hale S, Ganesh B, et al (2019) Does campaigning on social media make a difference? Evidence from candidate use of Twitter during the 2015 and 2017 U.K. Elections Commun Res 47(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650219872394

Brüggemann M, Wessler H (2014) Transnational communication as deliberation, ritual, and strategy. Commun Theory 24(4):394–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12046

Caiani M, Guerra S (2017) Euroescepticism, democracy and the media: Communicating Europe, contesting Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Canel MJ, Sanders K (2012) Government communication: an emerging field in political communication research. In: Semetko H, Scammell M (eds) Political Communication. SAGE, London

Clark N (2014) The EU’s information deficit: comparing political knowledge across levels of governance. Perspect Eur Politics Soc 15(4):445–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705854.2014.896158

Conrad M, Oleart A (2020) Framing TTIP in the wake of the Greenpeace leaks: agonistic and deliberative perspectives on frame resonance and communicative power. J Eur Integr 42(4):527–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1658754

De Wilde P, Michailidou A, Trenz HJ (2014) Converging on Euroscepticism: online polity contestation during European Parliament elections. Eur J Political Res 53(4):766–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12050

Duggan M (2015) Mobile messaging and social media 2015. Per Research Centre. https://apo.org.au/node/56763

Durand H, Mc Sharry J, Meade O, Byrne M, Kenny E, Lavoie L, Molloy J (2021) Content analysis of behaviour change techniques in government physical distancing communications for the reopening of schools during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. HRB Open Res 4(78):78

European Commission (2021) Safe vaccines against COVID-19 for the European population. Available via European Commission. https://bit.ly/3mLjudP

Fazekas Z, Adrian Popa S, Schmitt H et al. (2020) Elite‐public interaction on Twitter: EU issue expansion in the campaign. Eur J Political Res 60(2):376–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12402

Gainous J, Wagner KM (2014) Tweeting to power: The social media revolution in American politics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gattermann K (2020) Media personalization during European elections: the 2019 election campaigns in context. J Common Mark Stud 58:91–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13084

Gattermann K (2022) The personalization of politics in the European Union. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Giglietto F, Selva D (2014) Second screen and participation: a content analysis on a full season dataset of tweets. J Com 64(2):260–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12085

Gleason B (2018) Thinking in hashtags: exploring teenagers’ new literacies practices on twitter. Learn, Media Technol 43(2):165–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1462207

Gower K (2006) Public relations research at the crossroads. J Public Relat Res 18(2):177–190. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr1802_6

Graber DA (2003) The Power of Communication. Managing Information in Public Organizations. CQ Press, Washington

Graham T, Jackson D, Broersma M (2016) New platform, old habits? Candidates’ use of Twitter during the 2010 British and Dutch general election campaigns. N Media Soc 18(5):765–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814546728

Greer S, Ruitjer A (2020) EU health law and policy in and after the COVID-19 crisis. Eur J Public Health 30(4):623–624

Grunig LA, Grunig JE, Dozier DM (2003) Excellent public relations and effective organizations: A study of communication management in three countries. Routledge, New York

Gurevich A (2016) El tiempo todo en Facebook. Aposta Rev de Cienc Soc 69:217–238. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=49595243100

Halpern D, Valenzuela S, Katz JE (2017) We face, I tweet: How different social media influence political participation through collective and internal efficacy. J Computer-Mediated Com 22(6):320–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12198

Hagemann L, Abramova O (2023) Sentiment, we-talk and engagement on social media: Insights from Twitter data mining on the US presidential elections 2020. Internet Res 33(6):2058–2085. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-12-2021-0885

Hamřík L, Kaniok P (2022) Who’s in the spotlight? The personalization of politics in the European Parliament. JCMS J Common Mark Stud 60(3):673–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13281

Hänska M, Bauchowitz S (2019) Can social media facilitate a European public sphere? Transnational communication and the Europeanization of Twitter during the Eurozone crisis. Social Media + Society 5(3). 10.1177%2F2056305119854686

Holtz Bacha C (2004) Political communication research abroad: Europe. In: Lee Kaid L (ed) Handbook of political communication research. Routledge, New York, p 481-496

Jiménez Alcarria F, Tuñón J (2023) EU digital communication strategy during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign: Framing, contents and attributed roles at stake. Comm Soc 36(3):153–174. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.36.3.153-174

Jackson N, Lilleker D (2011) Microblogging, constituency service and impression management: UK MPs and the use of Twitter. J Legis Stud 17(1):86–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2011.545181

Jivkova Semova D, Requeijo Rey P, Padilla Castillo G (2017) Usos y tendencias de Twitter en la campaña a elecciones generales españolas del 20D de 2015: hashtags que fueron trending topic. Profesional de la Inf ón 26(5):824–837. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.05

Kaitatzi Whitlock S (2007) The missing European public sphere and the absence of imagined European citizenship: democratic deficit as a function of a common European media deficit. Eur Soc 9(5):685–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616690701412814

Langer AI, Sagarzazu I (2018) Bring back the party: personalisation, the media and coalition politics. West Eur Politics 41(2):472–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1354528

Likely F (2019) Exploring the Complexity of Global Strategic Communication Practice in Government. In: Sriramesh K, Verčič D (eds) The global public relations handbook. Routledge, New York, p 99–110

López Meri A, Casero Ripollés A (2017) Las estrategias de los periodistas para la construcción de marca personal en Twitter: posicionamiento, curación de contenidos, personalización y especialización. Rev Mediterr de Comunicación 8(1):59–73. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2017.8.1.5

Lopez Meri A, Marcos García S, Casero Ripollés A (2017) What do politicians do on Twitter? Functions and communication strategies in the Spanish elec-toral campaign of 2016. Profesional de la Inf ón 26(5):795–804. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.02

Luoma-aho, V, Canel, MJ, Sanders, K (2019) Global public sector and political communication. In: Sriramesh K, Verčič D (eds) The global public relations handbook. Routledge, New York, p 111–119

Maldonado B, Collins J, Blundell HJ, Singh L (2020) Engaging the vulnerable: a rapid review of public health communication aimed at migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. J Migr Health 1:100004

McAllister I (2007) The personalization of politics. In: Dalton R, Klingemann HD (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Political Behaviour. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 571–588

Meyer C (2009) Does European Union Politics become mediatized? The case of the European Commission. J Eur Public Policy 16(7):1047–1064. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760903226849

Niciporuc T (2014) Comparative analysis of the engagement rate on Facebook and Google Plus social networks. Proceedings of International Academic Conferences. https://ideas.repec.org/p/sek/iacpro/0902287.html#download

Nulty P, Theocharis Y, Popa SA et al. (2016) Social media and political communication in the 2014 elections to the European Parliament. Elect Stud 44:429–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.014

Oleinik et al. (2014) On the choice of measures of reliability and validity in the content-analysis of texts. Qual Quant 48(5):2703–2718

Parmelee JH, Bichard SL (2012) Politics and the Twitter revolution: How tweets influence the relationship between political leaders and the public. Lexington Books, New York

Paine KD (2011) Measure What Matters: Online Tools for Understanding Customers, Social Media, Engagement, And Key Relationships. Wiley, New York

Papagianneas S (2017) Rebranding Europe. Fundamentals for leadership communication. ASP editions, Brussels

Pedersen H, Rahat G (2021) Political personalization and personalized politics within and beyond the behavioural arena. Part Politics 27(2):211–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819855712

Pfetsch B, Adam S, Eschner B, Koompans R, Statham P (2010) The media’s voices over Europe: Issues salience, Openness and Conflict Lines in Editorials. The Making of a European Public Sphere. Media discourse and political contention. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 151–170

Pulido Polo M, Hernández Santaolalla V, Lozano González AA (2021) Institutional use of Twitter to combat the infodemic caused by the Covid-19 health crisis. Profesional de la Inf ón 30(1):e300119. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.ene.19

Rauh C, Bes BJ, Schoonvelde M (2020) Undermining, defusing, or defending European integration? Assessing public communication of European executives in times of EU politicization. Eur J Political Res 59(2):397–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12350

Rauh C (2022) Clear messages to the European public? The language of European Commission press releases 1985–2020. J of Eur Integration. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2022.2134860

Reinikainen H, Valentini C (2023) Digital corporate communication and public sector organizations. In: Luoma-Aho V, Badham M (eds) Handbook on Digital Corporate Communication. Edward Elgar Publishing, Massachusetts, p 400–412

Rivas de Roca R (2020) Transnational strategic communication on Twitter for the 2019 European Parliament elections. Zer 25(48):65–83. https://doi.org/10.1387/zer.21214

Salgado S, Bobba G (2019) News on events and social media: a comparative analysis of Facebook users’ reactions. Journal Stud 20(15):2258–2276. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2019.1586566

Schudson M (1995) The power of news. Harvard University Press, Harvard

Scherpereel J, Wohlgemuth J, Schmelzinger M (2016) The adoption and use of Twitter as a re- presentational tool among members of the European Parliament. Eur Politics Soc 18(2):111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2016.1151125

Silva BC, Proksch SO (2022) Politicians unleashed? Political communication on Twitter and in parliament in Western Europe. Pol Sci Res Meth 10(4):776–792. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.36

Šimunjak M, Caliandro A (2020) Framing #Brexit on Twitter: the EU 27’s lesson in message discipline? Br J Politics Int Relat 22(3):439–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120923583

Sloan L, Quan Haase A (eds) (2017) Social Media Research Methods. SAGE Publications, London

Smyrnaios N, Baisnée O (2023) Critically understanding the platformization of the public sphere. Eur J Com 38(5):435–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231231189046

Statham P (2016) Media Performance and Europe’s ‘Communication Deficit’: A Study of Journalists’ Perceptions. In: Bee C, Bozzini E (eds) Mapping the European Public Sphere. Routledge, New York, p117–140

Steward B (2017) Twitter as Method: Using Twitter as a Tool to Conduct Research. In: Sloan L, Quan Haase A (eds) Social Media Research Methods. SAGE Publications, London, p 251-265

Stieglitz S, Dang-Xuan L (2013) Social media and political communication: a social media analytics framework. Soc Netw Anal Min 3:1277–1291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-012-0079-3

Stier S, Bleier A, Lietz H, Strohmaier M (2018) Election campaigning on social media: politicians, audiences, and the mediation of political communication on Facebook and Twitter. Political Commun 35(1):50–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1334728

Stier S, Froio C, Schünemann WJ (2021) Going transnational? Candidates’ transnational linkages on Twitter during the 2019 European Parliament elections. West Eur Politics 44(7):1455–1481. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1812267

Thiel M (2008) European Public Spheres and the EU’s communication strategy: from deficits to policy fit? Perspect Eur Pol Soc 9(3):342–356

Touri M, Rogers SL (2013) Europe’s communication deficit and the UK press: framing the Greek financial crisis. J Contemp Eur Stud 21(2):175–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2013.815462

Trilling D, Tolochko P, Burscher B (2017) From newsworthiness to shareworthiness: How to predict news sharing based on article characteristics. J Mass Commun Q 94(1):38–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016654682

Tuñón J, Carral U (2019) Twitter como solución a la comunicación europea. Análisis comparado en Alemania, Reino Unido y España. Rev Lat de Comunicación Soc 74:1219–1234. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2019-1380

Tuñón J, Catalán D (2020) Comparing online campaigning strategies to host the European Medicines Agency. Profesional De La Información 29(2). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.mar.25

Van Aelst P, Sheafer T, Stanyer J (2012) The personalization of mediated political communication: a review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism 13(2):203–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427802

Vaccari C (2017) Onli gement in Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Political Commun 3(1):69–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1201558

Valentini C (2006) Manufacturing EU consensus: the reasons behind EU promotional campaigns. Glob Media J Mediterr Ed 1(2):80–96. https://bit.ly/3BqjMuI

Van Noije L (2010) The European paradox: A communication deficit as long as European integration steals the headlines. Eur J Com 25(3):259–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323110373460

Vergeer M, Hermans L (2013) Campaining on Twitter: Microblogging and online social networking as campaign tools in the 2010 general elections in the Netherlands. J Computer Mediated Commun 18(4):399–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12023

Vergeer M, Hermans L, Sams S (2013) Online social networks and micro-blogging in political campaigning: The exploration of a new campaign tool and a new campaign style. Part politics 19(3):477–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068811407580

Wolter LC, Chan Olmsted S, Fantapie Altobelli C (2017) Understanding Video Engagement on Global Service Networks—The Case of Twitter Users on Mobile Platforms. In: Bruhn M, Hadwich K (eds) Dienstleistungen 4.0. Springer Fachmedien, Wiesbaden, p 391-409

Wimmer RD, Dominick JR (1996) Mass Media Research: An Introduction. Cengage Learning, New York

Wischnewski M, Bruns A, Keller T (2021) Shareworthiness and motivated reasoning in hyper-partisan news sharing behavior on Twitter. Digital Journal 9(5):549–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1903960

Ziegele M, Weber M, Quiring O, Breiner T (2018) The dynamics of online news discussions: effects of news articles and reader comments on users’ involvement, willingness to participate, and the civility of their contributions. Inf Com Soc 21(10):1419–1435

Acknowledgements

This article is part of an European Chair funded by the Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA), belonging to the European Commission, Jean Monnet (Erasmus+), 'Future of Europe Communication in times of Pandemic Disinformation' (FUTEUDISPAN), Ref: 101083334-JMO-2022-CHAIR), directed between 2022 and 2025, from the University Carlos III of Madrid, by Professor Jorge Tuñón. However, the content of this article is the sole responsibility of the authors and EACEA cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained there.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiménez Alcarria, F., Tuñón Navarro, J. Stakeholders and impact (engagement) in EU digital communication strategies during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1325 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03820-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03820-w