Abstract

Academic dishonesty became more pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic. We explored university students’ motivations to commit academically dishonest acts during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our objectives were to 1) assess students’ perceptions of cheating opportunities, 2) evaluate their moral stance on cheating, 3) measure instances of cheating, and 4) determine if differences existed in students’ motivations to cheat. We conducted a cross-sectional survey with undergraduates at Texas A&M University. We found students perceived greater opportunities to cheat in online than in-person courses; however, most participants viewed themselves as having strong moral stances toward cheating and did not take opportunities to cheat. No differences were found in opportunities to cheat, moral stance on cheating, or opportunities taken to cheat when compared by gender, class, or estimated grade point average. Differences existed in moral stance on cheating when analyzed by religiosity; those with average religious beliefs had lower scores for moral stance on cheating than did those with less than or more than average religious beliefs. This confounding result merits further investigation. Our findings contribute to better understanding of students’ motivations to cheat. Further research is needed to understand the complex factors that influence students’ motivations to commit academically dishonest acts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Academic Dishonesty

Academic dishonesty, a form of unethical behavior in educational settings, and often referred to as academic misconduct, is a persistent issue in academia. Zhao et al. (2022) defined academic dishonesty as “intentionally carrying out forbidden behaviors to gain an unfair advantage in an academic context” (Zhao et al., 2021), while others (Rettinger, 2017; Waltzer & Dahl, 2020; Waltzer et al., 2021) determined academic dishonesty included behaviors such as cheating on exams, copying others’ homework and/or assignments, and plagiarism. We focused on the intentionality of academic misconduct, suggesting students have consciousness of engagement in prohibited acts of dishonest behavior.

Barnhardt (2016) described cheating in two ways; a) concretely, by specific actions that are considered cheating, such as copying homework, falsifying data, and unlawfully obtaining test answers; and b) abstractly, by identifying principles that define cheating, such as violating academic policies or seeking to gain an unfair advantage. According to McLachlan and Penier (2022), academic dishonesty includes a range of unethical behaviors or unauthorized actions that compromise the integrity of academic work, such as copying during exams, plagiarizing from sources without proper attribution, or using unauthorized materials. These academically dishonest behaviors are considered cheating. While definitions of academic cheating vary, we adopted Zhao et al.’s (2022) definition of academic cheating as the basis for studying students’ motivations to cheat at Texas A&M University during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Examples of academic cheating include plagiarism, such as using others’ works without citing sources, purchasing and submitting a paper, copying homework assignments in part or whole, and unlawfully obtaining test answers (Molnar & Kletke, 2012). Dawson (2020) defined cheating as “gaining an unfair advantage,” and e-cheating as “cheating that uses or is enabled by technology” (p. 4). Consequently, these definitions encompass two common forms of cheating (online and in-person).

Academic cheating is exacerbated in online learning; most students have admitted cheating at least once (Ali & Aboelmaged, 2020; Curtis & Vardanega, 2016). McGee (2020) observed a 20% increase in cheating claims at Texas A&M university throughout the 2020 fall semester, potentially attributable to the transition of online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic (Henton, 2021). We agree with Burgason et al.’s (2019) claim that when students cheat and do not face consequences of their cheating, they are encouraged to continue engaging in behaviors and actions consistent with academic misconduct.

Motivations to Commit Academic Dishonesty

What motivates students to cheat during online and/or in-person classes? Some might cheat because their classmates cheat too, while others may fear failing exams or courses, because of peer pressure or because it is easy to cheat (Noorbehbahani et al., 2022). Similarly, Sarita (2015) stated that peer pressure may lead students to find their peers’ academic cheating acceptable. Waltzer and Dahl (2023) found 63% of participants cheated because it was feasible; they concluded the most common motivations to cheat were feasibility, assignment goals, and peer relations. These findings affirm those of Yu et al. (2021) who found that cheating behavior among students may be influenced by the norms, values, and attitudes.

Students may resort to cheating because they think exams are unfair or not in keeping with current trends in education (Jantos, 2021). This claim is supported by other researchers who found that difficulties in learning caused by negative consequences such as stress, anxiety, and perceptions of unfairness, could be related to cheating (Meital et al., 2022; Wenzel & Reinhard, 2020). Adelrahim (2021) found stress and anxiety, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, created uncertainty in students that led some to perceive erroneously, their cheating was justified.

School environment and teaching method could influence students’ motivation to cheat.

Students who had strong connections to their schools were more likely to uphold their institutions’ ethical standards (Simon et al., 2004 as cited in Molnar & Kletke, 2012). Others (Kamarudin et al., 2024; Rundle et al., 2019) found that morality and norms, motivation for learning, and lack of opportunities to cheat were leading reasons why students avoided academic dishonesty. Furthermore, students’ perception of cheating opportunities and their choice to take these can be influenced by what they believe constitutes cheating (Reedy et al. 2021). This was supported by Djokovic et al. (2022), who based their study under the assumption that students often cheat because academic integrity rules and regulations are unknown to them.

Academic Dishonesty in Remote Learning

University honor codes highlight students’ obligations to comply with rules and procedures to follow when code violations arise (Tatum, 2022). Honor codes may reduce tendencies to commit academic misconduct; however, they have not prevented or reduced cheating in online exams (Corrigan-Gibbs et al., 2015). Texas A&M University promotes academic integrity for all with a student honor code that includes reporting (self and others) violations of the code (Schwartz et al., 2013). However, the increased incidence of unreported code violations in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic forced Texas A&M University to reconsider its academic honor code.

Online cheating increased when remote learning increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (Jenkins et al., 2023; Newton & Essex, 2024). Maryon et al. (2022) found that although the type of cheating has not changed, there has been a particular increase in academic dishonesty behaviors in courses that contain a laboratory experience element. Reedy et al. (2021) reported on students’ views that lacking supervision [during exams] made it easy to cheat. Many students reported being aware of peers cheating. Adzima (2020) found that anonymity in online learning was positively correlated with cheating behaviors. Similarly, Kapardis and Spanoudis (2021) found that students who reported cheating in the midterm did not cheat in the final because proctoring rigor increased, oral examinations were encouraged, and students were asked to confirm that the work they completed was theirs. This suggests that greater accountability and reducing the level of anonymity may have demotivated students to cheat.

In remote environments, examinations are reliant on technology, and because students access online tools, it is fair to assume their likelihood to cheat (e.g., materials, notes, textbooks, unauthorized collaboration with classmates, additional technological devices) was enhanced by the same technology used to deliver instruction and examinations (Noorbehbahani et al., 2022). The pandemic’s psychological impact caused students’ anxiety and stress, which may have influenced the likelihood of committing academically dishonest acts (Johnson-Clements et al., 2024). Jenkins et al. (2023) found some students’ mental health issues during the pandemic erroneously induced cheating behavior to satisfy self-perceived stressors in school. Similarly, Xu et al. (2022) interviewed students from different contexts and most of them claimed that their mental health and overall well-being were disrupted by the online learning environment.

However, these results varied depending on the context; students from the U.S felt that the online environment’s repetitiveness was tiresome, while students from Lebanon reported often having issues with the internet connection, which interfered with their learning.

Demographic Factors and Academic Dishonesty

Yazici et al. (2023) suggested demographic factors such as gender, age, religion, and personality type could affect students’ motives for academic cheating. Researchers explored these suggestions and selected demographic factors to study in relation to students’ motivations to cheat. Henderson et al. (2022) found that age, gender, language spoken at home, grades were related to students’ cheating behavior. Similarly, Beasley (2015) observed that student status had an influence in their motivations to cheat, as international students were more likely to cheat, get caught, and get reported than domestic students.

Yu et al. (2016) found a difference in students’ motivation to cheat when analyzed by gender; female students had fewer self-reported incidents of academic cheating. Females scored higher for subjective norms, moral attitude, and penalty enforcement, according to Zhang et al. (2017). Ghanem and Mozahem (2019) affirmed these findings, noting that female students cheat less, while identifying low grade point average (GPA) as a motivating factor for students to engage in academic cheating. Koscielniak and Bojanowska (2019) found a significant negative correlation between GPA and students’ involvement in cheating; incidences of cheating behavior decreased as students’ grade point averages increased.

Yu et al. (2016) further identified income as an influencing factor for cheating, finding that students coming from high-income families are less likely to engage in academic cheating than students coming from low-income families. The literature we explored did not reveal major findings in regard to the relation between household income and academic dishonesty. However, we encountered an interesting conflicting view with Chow et al. (2021), who found that male students who reported a higher family income were more likely to engage in academic dishonesty than students who reported the opposite.

Nelson et al. (2016) and Mildaeni et al. (2021) found that religiosity, or engaging in religious activities like attending church, was negatively related to academically dishonest behaviors. Hongwei et al. (2016), Ullah Khan et al. (2019), and Ridwan and Diantimala (2021), affirmed these findings; students with strong engagement in religious activities had less intention to commit academically dishonest acts than those who rarely were involved in religious activities.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed students’ perceptions of cheating on examinations and assignments (Newton & Essex, 2024). Likewise, instructors’ perceptions of acceptable levels of students’ cheating behaviors have changed with some expecting more than 50% of students engage in some cheating behaviors because instructors have limited capabilities to detect academic misconduct in online environments (Felski, 2025). The rapid rise of artificial intelligence (AI) since the pandemic ended further complicates educators’ abilities to deter and/or detect academic misconduct, in every educational environment. AI tools pose significant potential harm to educational institutions’ values and teachings of academic integrity. We believe the COVID-19 pandemic normalized some cheating behaviors, which may instigate more academic misconduct vis-vis AI-generated tools in postsecondary institutions.

Therefore, a need existed to explore factors affecting students’ cheating behaviors. The purpose of this research was to explore university students’ motivations to commit academic dishonesty during the COVID-19 pandemic. The objectives were to measure: 1) students’ perceptions of opportunities to cheat; 2) students’ moral stance on cheating; 3) students’ opportunities taken to cheat; and 4) to determine if significant differences existed in students’ cheating behaviors when examined by selected demographics.

Methods

This study was conducted as part of a larger project (IRB2021-1065 M), which used a descriptive survey design (Field, 2015; Fraenkel et al., 2019). This study was designed during the COVID-19 pandemic. One shortcoming in survey research is the reliance on self-reported data, which could be biased because of the topic (cheating).

Participants were undergraduates at Texas A&M University (United States of America), representing about 55,000 students during fall semester 2021. We chose Texas A&M University because one of its core values is integrity (Texas A&M University, 2021a), which is expected to be prioritized, upheld, and unstained by academic misconduct. Texas A&M University’s student honor code, which all students pledge to observe and practice, includes the oath, “to not lie, cheat, or steal or tolerate those who do” (Texas A&M University, 2021b). This oath is the antithesis of cheating; thus, Texas A&M University students became our primary population of interest for study about students’ motivations to cheat, juxtaposed to an institutional belief to never cheat. To ensure representativeness, stratified random samples were derived from diverse groups (e.g., freshmen to seniors and multiple colleges) of students enrolled in one of 16 ethics-based courses (n = 1,918) or one of 25 non-ethics-based courses (n = 3,394) comprising the accessible population (N = 5,312).

Samples were based on conservative 50/50 splits with a 5% sampling error and 95% confidence level (Dillman et al., 2014). These parameters showed approximately 350 participants would represent the population of 5,312; we rounded up the sample to 400 (n = 200/course type) to account for opt-outs. Only students who consented to participate could enter the survey. Only those who completed 50% or more of the questions were included in the data set.

We used established instruments (Jantos, 2021; Stankovska et al., 2019; Taşgın, 2018) to create our research instrument. The instrument’s first section measured students’ motivations to cheat. Three subsections (opportunities to cheat, moral stance on cheating, and opportunities taken to cheat) had six statements each (Jantos, 2021). Statements were measured on five-point scales (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = mostly disagree, 3 = partly agree/disagree, 4 = mostly agree, and 5 = strongly agree). Example statements included: “I had the opportunity to cheat in online courses”; “I could have had someone else complete my exams in online courses”; “I have moral reservations about cheating in online exams”; and “I prepared differently because I knew about opportunities to cheat”. Summed subsection scale coefficient alphas (αs = 0.70, 0.65, and 0.88, respectively) were deemed valid and reliable for use with university students (Jantos, 2021).

The last section gathered demographic information. Demographic questions were derived from previous research (Jantos, 2021; Stankovska et al., 2019; Taşgın, 2018) where demographic variables were found relevant in measuring students’ motivations to cheat. Demographic variables included gender (male/female), race/ethnicity (white/black/Hispanic/Asian/another), class (underclassmen/upperclassmen), college (nine choices), political views (conservative/moderate/liberal), religiosity (less than average beliefs/average/more than average beliefs), and estimated grade point average (1.99–2.99/3.00–4.00).

The dependent variables were opportunities to cheat, moral stance on cheating, and opportunities taken to cheat. Independent variables were selected demographic variables (i.e., gender, class, political views, religiosity, and estimated GPA). Dependent and independent variables were acquired without manipulation. Participants were reminded they could opt out of answering any question during collection.

Data collection began after receiving Institutional Review Board approval (IRB2021- 1065 M); collection occurred for four weeks in Fall 2021. Invitation emails included the purpose of the study, assurance of anonymity, consent forms, and instructions. The estimated time to complete the survey was 10–15 min. Respondents were informed repeatedly they could skip questions that made them uncomfortable.

From the 400 personalized invitations and five reminders to participate in the study, 282 responses (71%) were received, which were reduced to 247 because of partial or incomplete data (i.e., some respondents opted out or skipped sensitive questions about cheating). The final response rate was ~ 62%. From those 247 qualified responses, three groups emerged because respondents were randomly assigned to one of three sets of questions. This paper focuses on 88 respondents who answered questions related to their motivations to cheat. Respondents (Table 1) identified as female (48.3%), Caucasian (60.2%), upperclassmen (64.8%) in the business and engineering colleges (36.4%), who had conservative political views (40.9%) with more than average religious beliefs (38.6%), and an estimated GPA of 3.00 to 4.00 (67.1%).

Descriptive statistics were used to check for outliers, normality, skewness, and other outputs (Ott & Longnecker, 2015), and to analyze students’ motivations to cheat (opportunities to cheat, moral stance on cheating, and opportunities taken to cheat), and demographics. Objective 3 was analyzed using independent samples t-tests and ANOVA with partial Eta squared (η2) as a measure of effect size. All tests of significance were conducted with an a priori alpha level of 0.05. Noted limitations consisted of the possibility of biased answers because of self- reported data and possible underreporting of academic cheating because of anonymous response. The sample was limited to one university, which limited generalizability of the data to other universities or other contexts.

Results

Perceived Opportunities to Cheat

Table 2 shows participants mostly agreed (M = 4.01, SD = 1.05) there were more opportunities to cheat online than in traditional in-person courses. Similarly, they mostly agreed (M = 3.78, SD = 1.10) they had opportunities to cheat in online courses. Participants mostly agreed there were opportunities to cheat by using lecture notes during online exams (M = 3.56, SD = 1.23). The summed opportunity to cheat score (M = 18.76, SD = 4.26) showed that overall, participants mostly agreed they had numerous opportunities to cheat. The summed standard deviation showed there was consistent variability across participants, indicating that the perception of opportunities to cheat was uniform (Table 2).

Moral Stance on Cheating

Table 3 shows participants mostly agreed they wanted to be known as a good or a bad person (M = 4.35, SD = 1.01) and having their honest achievements shown in their studies (M = 4.33, SD = 0.88). Similarly, they mostly agreed they had scruples about cheating outside of school (M = 4.26, SD = 0.95). Overall, participants viewed themselves as having strong moral stances toward cheating (M = 22.90, SD = 5.12), indicating they would not cheat in exams, nor use Google to find answers, and to be known as a good, honest person (Table 3).

Opportunities Taken to Cheat

Participants partly agreed (M = 3.27, SD = 1.18) that most of their peers cheated in online courses. Subsequently, they mostly disagreed (M = 2.04, SD = 1.18) that they used unauthorized sources in course assignments (M = 1.91, SD = 1.11). Overall, the summed opportunities taken to cheat (M = 11.74, SD = 5.16) indicated few participants engaged in cheating behaviors (Table 4).

Students’ Cheating Behaviors

The third objective was to determine if significant differences existed in the dependent variables (i.e., opportunities to cheat, moral stance on cheating, and opportunities taken to cheat) when compared by selected independent variables (i.e., gender, class, political views, religiosity, and estimated GPA). Shapiro–Wilk tests showed that the variable opportunity to cheat was normally distributed (W = 0.99, p < 0.75); however, neither moral stance on cheating (W = 0.94, p < 0.001) nor the opportunity taken to cheat (W = 0.92, p < 0.001) were normally distributed. Given the sample size (N = 88), we examined the Normal Q-Q plots and determined that the distance between the dots and the line illustrated near normal distributions. Therefore, we contend that independent samples t-tests and ANOVA were appropriate tests to determine if significant differences in the dependent variables existed when analyzed by selected independent variables.

Independent samples t-tests were conducted but no significant differences (p < 0.05) were found in opportunities to cheat, moral stance on cheating, or opportunities taken to cheat when compared by gender, class, or estimated GPA (Table 5). Briefly, males and females did not differ from each other in their responses to opportunities to cheat, opinions about the moral stance on cheating, or in taking advantage of opportunities to cheat. Similarly, underclassmen (1st and 2nd year students) did not look for opportunities to cheat, have differing opinions about the morality of cheating, nor take opportunities to engage in cheating any different from upperclassmen (3rd through 5th year students). Finally, students who had lesser GPAs (1.99–2.99 on a 4.00-point scale) did not differ in their responses to opportunities to cheat, moral stance on cheating, or opportunities taken to cheat, any more than did students estimating greater GPAs (3.00–4.00) (Table 5). As a reminder, participants were reminded frequently that they could skip questions that made them uncomfortable, considering the topic of cheating in a population who esteemed the core value of integrity. Therefore, not all respondents answered every question, resulting in subgroups’ total responses being less than the full group response.

Table 6 shows descriptive statistics for the DVs by groups for political views and religiosity. As a group, respondents’ perceptions of opportunities to cheat were similar (M = 17.02, SD = 4.44). Their moral views on cheating were consistent, regardless of political view (M = 22.95, SD = 5.14). Likewise, their tendency to take opportunities to cheat (M = 11.75, SD = 5.20) was similar across political views. Regarding religiosity, overall results mirrored those found across political views, including their perceived opportunities to cheat (M = 17.03, SD = 4.44), moral stance on cheating (M = 22.95, SD = 5.14), and opportunities taken to cheat (M = 11.75, SD = 5.20).

Table 7 displays one-way ANOVA results for opportunities to cheat, moral stance on cheating, and opportunities taken to cheat by political views and religiosity. No significant differences existed in the DVs when analyzed by political views. However, a significant difference existed between groups’ moral stance on cheating, F(2,80) = 10.67, p < 0.001, when analyzed by religious beliefs. A large effect (η2 = 0.22) was produced as the practical difference between groups (Table 7).

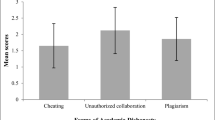

Post hoc tests (Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference; HSD) showed those with average religious beliefs had a significantly lower score (M = 18.27, SD = 5.48) for moral stance on cheating, than did those with less than average (M = 23.13, SD = 4.69) or more than average (M = 24.85, SD = 4.10) religious beliefs (Table 8).

Discussion and Conclusions

Students perceived more opportunities to cheat were present in online than in-person courses. We believe the lack of physically present instructors and/or peers in online settings likely contributed to these perceptions. Dawson (2020) and Yazici et al. (2023) found the way in which online courses are structured can increase opportunities to cheat. Online courses reduce physical connections formed between students and instructors during in-person, face-to-face courses. Consequently, this disconnect may increase students’ perceived opportunities to cheat and lead some to believe cheating is acceptable, producing guilt-free feelings when committing academically dishonest acts (Adzima, 2020). Corrigan-Gibbs et al. (2015) addressed the need for educators to strengthen assessment methods and guidelines to reduce perceived opportunities to cheat. Dawson (2020) mentioned strategies such as using open-ended questions that encourage students to think critically and using more rigorous proctoring during exams. Maryon et al. (2022) found a particular increase in academic dishonesty behaviors in online courses that contain a laboratory element, which suggests a challenge for instructors to find appropriate approaches to effectively teach and manage online laboratory experiences.

We did not observe significant differences in perceived opportunities to cheat, moral stance on cheating, or opportunities taken to cheat when analyzed by gender, class, or estimated GPA. Our findings conflict with Henderson et al. (2022) and Yu et al. (2016) who reported GPA and class as relevant to academic dishonesty. We affirmed Kapardis and Spanoudis’ (2021) findings of no significant differences in students’ engagement in academic cheating regardless of mode of instruction when examined by gender. Further research should explore these discrepancies, which may have been influenced by sample characteristics, research context, definitions of academic dishonesty, and other factors.

Political views were not a significant factor for students’ perceived opportunities to cheat, moral stance on cheating, or opportunities taken to cheat in our study. Yu et al. (2016) found no association between political affiliation and academic dishonesty. However, we found significant differences between students’ moral stance on cheating when examined by religiosity. Students with average religious beliefs had significantly lower summed moral stance on cheating scores than those with less than average and more than average religious beliefs. These are confounding results. Logically, we assume students with more than average religious beliefs would have strong moral stances against cheating, and those with average or less than average would have less strong (i.e., lower scores) moral views toward cheating. Mildaeni et al. (2021) found religiosity was significantly negatively correlated to academic dishonesty, suggesting as one’s religious convictions increased, engaging in academically dishonest acts decreased. There exists a need to investigate further how religiosity may affect students’ moral stance on cheating.

Pandemic-induced stress and fear of failure that some felt because of new and challenging learning environments, increased motivations for cheating, which may have caused higher rates of academic dishonesty (Meital et al., 2022). However, despite increased instances of cheating, many students claimed they held strong moral and ethical stances against cheating. Rundle et al. (2019) found morality was one reason why students did not engage in academic cheating. Kamarudin et al. (2024) concluded that students who believed they would not engage in academic dishonesty because of high moral standards were unlikely to do so. More research is needed to learn if academic cheating can be discouraged by fostering a culture of integrity, even when students perceive opportunities to cheat exist in online and in-person classes.

Waltzer and Dahl (2023) mentioned other factors that played a role in students’ motivations to cheat. Reedy et al. (2021) suggested that in some cases, a lack of clarity in the instructions about what resources could be used caused confusion about what was considered cheating. Adzima (2020) considered students’ lack of knowledge and understanding of an institutional integrity policy (i.e., honor code) could contribute to cheating.

Our findings contribute to better knowledge about why students are motivated to cheat, and their perceptions of committing academically dishonest acts. We found that perceptions of opportunities to cheat made it more likely for some to engage in cheating. These findings have implications for educators to design courses with clear guidelines combined with innovative ways to assess student’s knowledge to reduce opportunities to cheat. Djokovic et al. (2022) found that increasing awareness of what constitutes cheating and emphasizing the seriousness of committing academic dishonesty could change students’ perceptions and attitudes toward cheating behaviors. Educators should create interventions based on students’ individual experiences to control and prevent academic dishonesty (Jenkins et al., 2023; Perez et al., 2024). Such interventions may include programs, resources, or actions that account for individual motivations to cheat. Our results raise awareness about integrating conversations about honesty, integrity, and academic dishonesty, before and during the semester.

We believe more research is needed to identify factors affecting students’ motivations to cheat. Longitudinal studies should explore the causalities of cheating behavior. We recommend research in cross-cultural comparisons to explore if students’ motivations for cheating and/or acceptability of cheating behavior varies by culture, which may have implications for international students in U.S. universities.

Researchers should study changes in students’ motivations to cheat as learning environments evolve and reevaluate the effectiveness of existing academic policies intended to promote a culture of integrity. We believe universities should strengthen their support systems for students’ positive mental health through strategies that relieve stress and academic pressure that may induce academic dishonesty. Likewise, educators teaching online courses should connect with students more often during the semester to avert the lack of face-to-face communication, which may cause some students indifference toward taking opportunities to cheat.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Change history

31 March 2025

The original online version of this article was revised: The p-value and Eta-squared value should not be merged, but should be presented in separate columns, as indicated by the table header.

05 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-025-09625-z

References

Adelrahim, Y. (2021). How COVID-19 quarantine influenced online exam cheating: A case of Bangladesh university students. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University. 56(1). https://doi.org/10.35741/issn.0258-2724.56.1.18

Adzima, K. (2020). Examining online cheating in higher education using traditional classroom cheating as a guide. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 18(6), 476–493. https://doi.org/10.34190/JEL.18.6.002

Ali, I., & Aboelmaged, M. (2020). A bibliometric analysis of academic misconduct research in higher education: Current status and future research opportunities. Accountability in Research, 27(6), 362–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.202.1836620

Barnhardt, B. (2016). The “epidemic” of cheating depends on its definition: A critique of inferring the moral quality of “cheating in any form”. Ethics & Behavior, 26(4), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2015.1026595

Beasley, E. M. (2015). Comparing the demographics of students reported for academic dishonesty to those of the overall student population. Ethics & Behavior, 26(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2014.978977

Burgason, K. A., Sefiha, O., & Briggs, L. (2019). Cheating is in the eye of the beholder: An evolving understanding of academic misconduct. INnovative Higher Education, 44, 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-019-9457-3

Chow, H. P. H., Jurdi-Hage, R., & Hage, H. S. (2021). Justifying academic dishonesty: A survey of Canadian university students. International Journal of Academic Research in Education, 7(1), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.17985/ijare.951714

Corrigan-Gibbs, H., Gupta, N., Northcutt, C., Cutrell, E., & Thies, W. (2015). Measuring and maximizing the effectiveness of honor codes in online courses. In Proceedings of the Second (2015) ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale (pp. 223–228). ACM.

Curtis, G. J., & Vardanega, L. (2016). Is plagiarism changing over time? A 10-year time-lag study with three points of measurement. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(6), 1167–1179. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1161602

Dawson, P. (2020). Defending assessment security in a digital world: Preventing e-cheating and supporting academic integrity in higher education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429324178

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. John Wiley & Sons.

Djokovic, R., Janinovic, J., Pekovic, S., Vuckovic, D., & Blecic, M. (2022). Relying on technology for countering academic dishonesty: The impact of online tutorial on students’ perception of academic misconduct. Sustainability, 14(3), 1756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031756

Felski, E. (2025). Have students’ perceptions of cheating changed post-pandemic? Studies in Higher Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2437057

Field, A. P. (2015). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics (4th ed.). SAGE.

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. (2019). How to design and evaluate research in education (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Ghanem, C. M., & Mozahem, N. A. (2019). A study of cheating beliefs, engagement, and perception–The case of business and engineering students. Journal of Academic Ethics, 17, 291–312.

Henderson, M., Chung, J., Awdry, R., Mundy, M., Bryant, M., Ashford, C., & Ryan, K. (2022). Factors associated with online examination cheating. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2022.2144802

Henton, L. (2021, May 13) Integrity, communication key to avoiding academic misconduct. Texas A&M Today. Available online: https://today.tamu.edu/2021/05/13/integrity-communication-key-to-avoiding-academic-misconduct/. Accessed 15 Mar 2024.

Hongwei, Y., Glanzer, P. L., Johnson, B. R., Sriram, R., & Moore, B. (2016). The association between religion and self-reported academic honesty among college students. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 38(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2016.1207410

Jantos, A. (2021). Motives for cheating in summative e-assessment in higher education—a quantitative analysis. In EDULEARN21 Proceedings (pp. 8766–8776). IATED.

Jenkins, B. D., Golding, J. M., Le Grand, A. M., Levi, M. M., & Pals, A. M. (2023). When opportunity knocks: College students’ cheating amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Teaching of Psychology, 50(4), 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/00986283211059067

Johnson-Clements, T. P., Curtis, G. J., & Clare, J. (2024). Testing a psychological model of post- pandemic academic cheating. Journal of Academic Ethics, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-024-09561-4

Kamarudin, N. A., Sopian, A., Hamzah, F., & Sharifudin, M. A. S. (2024). Motivational perspectives on student cheating behaviour: Toward an integrated model of academic dishonesty. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 14(3), 1116–1125. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v14-i3/21137

Kapardis, M. K., & Spanoudis, G. (2021). Lessons learned during Covid-19 concerning cheating in e-examinations by university students. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(2), 506–518. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-05-2021-0105

Koscielniak, M., & Bojanowska, A. (2019). The role of personal values and student achievement in academic dishonesty. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1887.

Maryon, T., Dubre, V., Elliott, K., Escareno, J., Fagan, M. H., Standridge, E., & Lieneck, C. (2022). COVID-19 Academic integrity violations and trends: A rapid review. Education Sciences, 12(12), 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120901

McGee, K. (2020, December 16) Texas A&M investigating “large scale” cheating case as universities see more academic misconduct in era of online classes. The Texas Tribune. Available online: https://www.texastribune.org/2020/12/16/texas-am-chegg-cheating/. Accessed 15 June 2024.

McLachlan, J. C., & Penier, I. (2022). Academic cheating: How can we detect and discourage it? Technologies in biomedical and life sciences education: Approaches and evidence of efficacy for learning (pp. 287–311). Springer International Publishing.

Meital, A., Noa, S., & Niva, D. (2022). Two sides of the coin: Lack of academic integrity in exams during the corona pandemic, students’ and lecturers’ perceptions. Journal of Academic Ethics, 20(2), 243–263.

Mildaeni, I., Herdian, H., & Wahidah, F. (2021). The role of academic stress and religiosity on academic dishonesty. Research on Education and Psychology, 5(1), 31–40.

Molnar, K. K., & Kletke, M. G. (2012). Does the type of cheating influence undergraduate students’ perceptions of cheating? Journal of Academic Ethics, 10(3), 201–212.

Nelson, M. F., James, M. S. L., Miles, A., Morrell, D. L., & Sledge, S. (2016). Academic integrity of millennials: The impact of religion and spirituality. Ethics & Behavior, 27(5), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1158653

Newton, P. M., & Essex, K. (2024). How common is cheating in online exams and did it increase during the COVID-19 pandemic? A systematic review. Journal of Academic Ethics, pp 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-023-09485-5

Noorbehbahani, F., Mohammadi, A., & Aminazadeh, M. (2022). A systematic review of research on cheating in online exams from 2010 to 2021. Education and Information Technologies, 27(6), 8413–8460.

Ott, R. L., & Longnecker, M. T. (2015). An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis (7th ed.). Cengage Learning Inc.

Perez, J. A., Zapanta, R. D., Heradura, R. P., & Napicol, S. C. (2024). The drivers of academic cheating in online learning among Filipino undergraduate students. Journal of Ethics & Behavior, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2024.2328597

Reedy, A., Pfitzner, D., Rook, L., & Ellis, L. (2021). Responding to the COVID-19 emergency: Student and academic staff perceptions of academic integrity in the transition to online exams at three Australian universities. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 17(1), 9.

Rettinger, D. A. (2017). The role of emotions and attitudes in causing and preventing cheating. Theory Into Practice, 56(2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2017.1308174

Ridwan, R., & Diantimala, Y. (2021). The positive role of religiosity in dealing with academic dishonesty. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1875541

Rundle, K., Curtis, G. J., & Clare, J. (2019). Why students do not engage in contract cheating. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02229

Sarita, R. D. (2015). Academic cheating among students: Pressure of parents and teachers. International Journal of Applied Research, 1(10), 793–797.

Schwartz, B. M., Tatum, H. E., & Hageman, M. C. (2013). College students’ perceptions of and responses to cheating at traditional, modified, and non-honor system institutions. Ethics & Behavior, 23(6), 463–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2013.814538

Stankovska, G., Dimitrovski, D., Memedi, I., & Ibraimi, Z. (2019). Ethical sensitivity and global competence among university students. Bulgarian Comparative Education Society, 17, 132–138.

Taşgın, A. (2018). The relationship between pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards research and their academic dishonesty tendencies. International Journal of Progressive Education, 14(4), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.29329/ijpe.2018.154.7

Tatum, H. E. (2022). Honor codes and academic integrity: Three decades of research. Journal of College and Character, 23(1), 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2021.2017977

Texas A&M University. (2021a). Purpose & values. Available online: https://www.tamu.edu/about/purpose-values.html. Accessed on July 1 2024.

Texas A&M University. (2021b). Student rules. Available online: https://student-rules.tamu.edu/. Accessed July 1 2024.

Ullah Khan, I., Khalid, A., Anwer Hasnain, S., Ullah, S., & Ali, N. (2019). The impact of religiosity and spirituality on academic dishonesty of students in Pakistan. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences, 8(3), 381–398. Available online: https://european-science.com/eojnss/article/view/5525. Accessed 15 June 2024.

Waltzer, T., & Dahl, A. (2020). Students’ perceptions and evaluations of plagiarism: Effects of text and context. Journal of Moral Education, 50(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2020.1787961

Waltzer, T., & Dahl, A. (2023). Why do students cheat? Perceptions, evaluations, and motivations. Ethics & Behavior, 33(2), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2022.2026775

Waltzer, T., Samuelson, A., & Dahl, A. (2021). Students’ reasoning about whether to report when others cheat: Conflict, confusion, and consequences. Journal of Academic Ethics, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09414-4

Wenzel, K., & Reinhard, M. A. (2020). Tests and academic cheating: Do learning tasks influence cheating by way of negative evaluations? Social Psychology of Education, 23(3), 721–753.

Xu, Z., Pang, J., & Chi, J. (2022). Through the COVID-19 to prospect online school learning: Voices of students from China, Lebanon, and the US. Education Sciences, 12(7), 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12070472

Yazici, S., YildizDurak, H., AksuDünya, B., & Şentürk, B. (2023). Online versus face-to-face cheating: The prevalence of cheating behaviours during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic among Turkish University students. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39(1), 231–254.

Yu, H., Glanzer, P. L., & Johnson, B. R. (2021). Examining the relationship between student attitude and academic cheating. Ethics & Behavior, 31(7), 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2020.1817746

Yu, H., Glanzer, P. L., Sriram, R., Johnson, B. R., & Moore, B. (2016). What contributes to college students’ cheating? A study of individual factors. Ethics & Behavior, 27(5), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1169535

Zhang, Y., Yin, H., & Zheng, L. (2017). Investigating academic dishonesty among Chinese undergraduate students: Does gender matter? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(5), 812–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1411467

Zhao, L., Mao, H., Compton, B. J., Peng, J., Fu, G., Fang, F., Heyman, G., & Lee, K. (2022). Academic dishonesty and its relations to peer cheating and culture: A meta-analysis of the perceived peer cheating effect. Educational Research Review, 36, 100455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100455

Zhao, L., Zheng, Y., Mao, H., Zheng, J., Compton, B. J., Fu, G., Heyman, G. D., & Lee, K. (2021). Using environmental nudges to reduce academic cheating in young children. Developmental Science, 24, e13108. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13108. 1–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants for their time. Special thanks to Jose Solis for assistance in collecting data and Dr. Holli Leggette for guidance and feedback in writing processes.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

This research did not involve an experiment; it was a survey only. Informed Consent, in the form of an online Informed Consent Script, was posted and required participants’ consent prior to gaining access to the survey.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Research Involving Human Participants

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Texas A&M University (protocol code IRB2021-1065M and approved 08/31/2021).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The p-value and Eta-squared value should not be merged, but should be presented in separate columns, as indicated by the table header.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benitez, J.A., Wingenbach, G. Masks Off: Exploring Undergraduates’ Motivations to Cheat During COVID-19. J Acad Ethics (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-025-09616-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-025-09616-0