Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to investigate whether the narrative tone of annual reports is influenced by profitability, bankruptcy risk, and pandemic in the context of Vietnam. The study applies the necessary regression analysis steps such as ordinary least squares (OLS), random effects model (REM), fixed effects model (FEM), and feasible generalized least squares (FGLS). Bootstrapping and System Generalized Method of Moments (SGMM) methods are used to test the robustness and address endogeneity and dynamic relationships in the data. The findings show that net tones increase while negative tones decrease in companies with high profitability. Companies at risk of bankruptcy use more negative tone and less net tone than companies that are not at risk of bankruptcy. The study also affirms that bankruptcy risk moderates the relationship between profitability and negative tone. During the COVID-19 pandemic, companies used more positive and negative tones than they did before the pandemic. After the COVID-19 situation stabilized, positive tones were used more, and negative tones were used less than during the outbreak. The research results also recognized that companies do not intend to hide information through impression management when faced with difficult economic conditions. This study has practical implications for investors and information users when considering management disclosures through the narrative tone of annual reports. To our knowledge, this is the first study (1) in an emerging market in the East—where there are fundamental cultural and linguistic differences compared to Western countries, (2) to build a list of Vietnamese words and phrases expressing emotional nuances used in finance and accounting, and (3) refers to the narrative tone of annual reports across different groups of companies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The narrative content of the annual report is an essential factor in improving the quality of corporate reporting (Beattie et al., 2004). Increasingly, this content is becoming longer, more complex, and vital, serving as an essential source of information (Rutherford, 2005, 2018). Narratives are simple impression management tools and channels for disseminating price-sensitive information (Yekini et al., 2016) and to help understand business sustainability (Williams et al., 2021). The information system measured and provided by traditional accounting cannot meet the information needs of today’s stakeholders, such as information about company goals, risks, business risks, social responsibility, and sustainable development. Public confidence in the output accounting numbers of traditional systems declines over time. After the consecutive accounting scandals in the United States, such as Enron, WorldCom, Tyco International, and Lehman Brothers, the need for narrative disclosure was further fueled.

Accounting narratives have also attracted renewed attention (Beattie, 2014; Czarniawska, 2017; Rutherford, 2018). Different ways of expressing business performance have motivated more and more studies on the correlation between narrative content in annual reports and company business performance (Qian and Sun, 2021). Managers express business performance explicitly or implicitly through narrative content in annual reports or executive letters. This approach entails comparing the frequency rates of these word categories with expectations derived from the performance and the character of the preparer. Consequently, examining the narrative tone included in the annual report and financial analysis will provide an in-depth understanding of the underlying essence of the disclosed content. This will illuminate whether the information is being effectively communicated or intentionally concealed.

Multiple studies have provided empirical evidence indicating that the narrative tone of annual reports may act as a predictor of profitability (Kang et al., 2018; Tran et al., 2023) and the company’s bankruptcy risk (Lohmann and Ohliger, 2020; Lopatta et al., 2017). Studies also show a correlation between the narrative tone of a company’s reports and its profitability and bankruptcy risk (Alshorman and Shanahan, 2022; Aly et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2018; Mućko, 2021).

The main objective of this study is to contribute further evidence on the impact of profitability, bankruptcy risk, and pandemic on the narrative tone used in annual reports in an emerging market. It aims to answer the following questions: (1) Will the narrative tone of the annual report be influenced by profitability, bankruptcy risk, and the pandemic? (2) Does a difference in narrative tone exist between profitable and unprofitable companies? (3) Does a difference in narrative tone exist between companies experiencing financial difficulties and at risk of bankruptcy and those financially non-distressed and not at risk of bankruptcy? and (4) Does the narrative tone of companies’ annual reports before, during, and beyond the pandemic differ?

Compared with previous studies, our study has specific differences. First, studies on the correlation between narrative content in annual reports and profitability are mainly conducted in Western developed countries such as the UK, US, Australia, etc. Our research chooses an emerging market in the Orient, Vietnam. With unique and outstanding cultural characteristics, Vietnam represents Eastern culture in research (Tran et al., 2023). The fundamental cultural and linguistic differences between Western and Eastern countries provide an appropriate context for considering the importance of narratives in annual reports.

Second, to analyze the narrative tone of annual reports, previous studies have used available software such as Diction, Henry, L&M, and LIWC (Alshorman and Shanahan, 2022; Hajek et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2018; Mućko, 2021). These software use the English language. Unlike most published studies, we built our list of words and phrases in Vietnamese that represent emotional nuances for the language used in finance and accounting. This list of positive and negative words and phrases can become a valuable reference for future research conducted in the Vietnamese context.

Third, previous studies on narrative tone in annual reports in Vietnam have not clarified managers’ purposes. Whether Vietnamese managers’ behavior differs from those in developed countries is still unanswered. For the first time, we cover a completely different narrative tone in annual reports across different groups of companies. They are profitable and unprofitable companies, companies at risk of bankruptcy and companies not at risk of bankruptcy, and the stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (before, during, and after) that companies have experienced. From there, we consider the manager’s motivation for using language in the annual report, whether communication, publication, or manipulation.

Our research results are directly relevant to the yearly debates about the strengths and weaknesses of annual reports of listed companies with the best annual reports on the Vietnamese stock market (Pham, 2019; Vietnam Institute of Directors—VIOD, 2023). To clarify this issue, we collected research data from 468 officially listed non-financial companies in Vietnam over nine years with 250,013 reporting pages. We realized that managers often use a positive tone in companies with high profitability, and a negative tone is rarely used in annual reports. When business operations are highly effective, managers want to promote information widely and have no intention of hiding their business situation.

In contrast, the study found no difference in the use of a positive tone in annual reports between profitable and unprofitable companies. However, unprofitable companies used more negative tones than profitable companies. For net tone, low-profitability firms disclose less information than high-profitability firms. The study determined that financially distressed companies used more negative and less net tones. Regarding positive tone, the study did not find statistical evidence for a difference between companies at risk of bankruptcy and companies not at risk of bankruptcy. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the study realized that companies used more positive and negative tones but fewer net tones than before the pandemic. After COVID-19 was under control, positive and negative tones were expressed more, and negative tones were expressed less than during the pandemic.

The research results have provided empirical evidence for foundational theories such as impression management, agency, and signaling theories. The authors discovered managers’ motivations in expressing narrative tone through different aspects and contexts. Managers often use the narrative tone in annual reports to convey or manipulate information, hide difficulties, cover up shortcomings, or exaggerate the advantages of the companies or management teams. This means the information in annual reports and other media may not fully reflect reality. However, investors and stakeholders are still very interested in the narrative content in reports because it is an essential source of information that helps them evaluate the performance of companies. Therefore, this study recommends that investors and stakeholders carefully consider and analyze the narrative tone in reports before using the information to make investment decisions.

Our research stems from the following motivations: (i) Researchers’ growing interest in narrative content in annual reports. Accounting research has seen a narrative turn, similar to many other social sciences (Beattie, 2014; Czarniawska, 2017; Rutherford, 2018); (ii) Recent debates about the purpose of managers’ narrative disclosures to communicate convey information to shareholders or manipulate, impression management; (iii) Researchers’ interest in textual analysis methods in the fields of finance and accounting, especially the application of machine learning and deep learning methods, and (iv) The lack of research on this topic in Eastern countries, especially emerging markets.

The article is structured into five sections. Following the Introduction, section “Theoretical basis, literature review, and hypothesis development” presents the theoretical basis, research overview, and hypothesis development. This section aims to identify gaps, confirm the uniqueness of the study, and present arguments to propose the research hypotheses. This is followed by the research design section (section “Research design”). This section includes the research data, the research model, and how the variables in the model were measured. Section “Results and discussions” presents the results and discusses the research findings. Finally, conclusions and recommendations are presented.

Theoretical basis, literature review, and hypothesis development

Theoretical basis

Many previous studies on narrative tone have used several traditional theories in management, communication, and psychology to explain why and how discourse content conveys value-related information (Qian and Sun, 2021). However, previous studies have not highlighted the theories that define the relationship between profitability, bankruptcy risk, pandemics, and the narrative tone used in annual reports. Meanwhile, impression management, agency, and signaling theories can address those limitations. Therefore, to explain more comprehensively and thoroughly the aspects related to the impact of profitability, bankruptcy risk, and the pandemic on the narrative tone of companies’ annual reports, we combine, intertwine, and integrate these three theories.

Impression Management Theory (Goffman, 1959; Naegele and Goffman, 1956) refers to the management behavior of strategically selecting, displaying, and presenting narrative information in corporate documents. When applied to the business field, this theory emphasizes managers’ tendency to project a positive image of their company to various stakeholders. They attempt to influence the public’s perception or impression of their company’s image by manipulating and controlling the information provided to the outside world. This behavior is intended to “distort” the public’s perception of the company’s achievements and influence their impression of its performance and prospects (Leung et al., 2015). Impression management helps managers manage accounting data and convey a company image to customers, investors, and partners (Beattie, 2014). Impression management also considers whether the report preparer’s behavior manipulates the report content to hide the company’s actual business performance (Abou-El-Sood and El-Sayed, 2022). Merkl-Davies and Brennan (2007) argue that many companies use complex tactics to shape external stakeholders’ perceptions of their performance and prospects. Bhana (2009) finds that companies’ top and bottom groups like to highlight good news and blame the external environment for bad news.

According to agency theory (Jensen and Meckling, 1976), management’s actions that maximize profits may harm the interests of shareholders. Through earnings management practices, management can influence and manipulate information users’ perceptions of corporate performance for various motives (Abou-El-Sood and El-Sayed, 2022). This theory suggests that managers of profitable firms tend to provide more information to amplify their achievements and gain investors’ trust in management. The management team attempts to foster a perception of solid management capabilities by emphasizing positive corporate news while minimizing the significance of negative news (Qian and Sun, 2021).

Signaling theory plays a significant role in explaining the presence of both positive and negative tones inside the annual report. Signaling theory suggests that managers strategically transmit signals to investors to reduce asymmetric information (Morris, 1987). Managers with positive personal attributes tend to employ a greater frequency of positive language. In contrast, managers who possess negative unique characteristics tend to exhibit a decreased usage of positive language (Tran et al., 2023). Due to the issue of asymmetric information, corporations engage in signals to convey specific information to investors, thereby demonstrating their superiority relative to other firms within the market to attract investment and bolster their overall reputation (Shehata, 2014; Verrecchia, 1983).

Literature review

Czarniawska (2017) believes that the narrative turn in social science research began during the 1970s and has grown in popularity since the 1980s. Using narrative tools within accounting documents has witnessed growth and diversification in accounting studies. This includes incorporating conventional and narratological rhetorical tools (Czarniawska, 2017). Rutherford (2018) asserts that the academic community studying accounting narratives through “narrative turn” approaches is sufficiently sizable to support significant intellectual debates on various research topics and methodologies, though not on a massive scale. Adelberg (1979) pointed out two possible functions of narrative: communication and manipulation. Researchers can use automated techniques to analyze corporate disclosures to find hidden clues and unobserved information in the reports of intermediaries and influencers to user decision-making.

Previous studies have used dictionary-based and machine-learning approaches to measure narrative tone. Regarding machine learning, traditional machine-learning methods were used in the studies of Brown and Tucker (2011), Hajek et al. (2014), Huang et al. (2014) and Li (2010). Recently, machine-learning methods with automated techniques associated with deep learning have been used in studies (Bochkay et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2023). Bochkay et al. (2023) also assert that contemporary techniques in natural language processing, such as deep learning and topic modeling, will become the advanced textual analysis methods in accounting. In recent studies, Fontanella et al. (2024) use a computational linguistic approach to review the literature systematically, while Arora et al. (2022) explore Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg’s Facebook posts to highlight key features in her crisis communication during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Researchers have used various methods to evaluate the correlation between narrative tone and profitability. Kang et al. (2018) used the narrative content to determine the relationship between evaluation information created by company managers’ output and these companies’ performance. They confirm that current profitability positively impacts the narrative tone. Aly et al. (2018) measured the bidirectional relationship between financial performance and tone by manually counting the number of positive and negative words in the annual reports. Their research indicates a two-way relationship between profitability and narrative tone.

In addition to profitability, bankruptcy risk analysis is also of direct interest to many stakeholders in making decisions based on the likelihood of bankruptcy of companies (Buzgurescu and Elena, 2020). The question is whether the language used in the annual report accurately reflects the company’s bankruptcy risk. Lopatta et al. (2017) confirmed that the 10-K reports of bankrupt companies contained significantly more negative language than reports of healthy companies. Lohmann and Ohliger (2020) demonstrate that based on structural and linguistic factors and qualitative information in annual reports, it is possible to accurately distinguish companies that have gone bankrupt and those that are solvent but facing financial difficulties.

According to Cherry et al. (2023), economic stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic can lead to unexpected changes in organizational performance. Therefore, the question of how the information disclosure practices of managers of these companies have changed during the COVID-19 epidemic has become contextually relevant. Non and Ab Aziz (2023) posit that companies apply a variety of emotional tones when communicating with stakeholders. Most companies use negative emotions to express their concerns about how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected their business.

Hypothesis development

Mućko (2021) asserts that according to positive accounting theory, managers can use their discretion over narrative reporting to enhance the signaling value of profitability and improve signal quality. At the same time, they can be manipulative or distort the signal value of returns for opportunistic reasons specific to the company’s situation and performance. Including more forward-looking estimates in the report will lead to changes in income measures, but it is believed to provide better information for making economic decisions (Barth, 2006).

Some research results support signaling and agency theories in explaining managers’ tone in annual reports. Li’s (2010) findings confirm the existence of a positive correlation between the narrative tone of forward-looking statements and a company’s current performance. When a company performs favorably, its leadership communicates its prospects more optimistically. Smith et al. (2011) point out that word-based variables in the chairman’s statement significantly correlate to firm performance. Aly et al. (2018) and Kang et al. (2018) confirm that current profitability positively influences the narrative tone. Mućko (2021) demonstrates that profitability significantly affects positive attitudes toward social responsibility disclosures. This indicates that managers use the optimistic spirit of social responsibility disclosure to enhance the reception of positive financial performance. Alshorman and Shanahan (2022) also suggest that more positive and less negative words impact profitability. From there, research hypothesis H1 is proposed as follows:

- H1a: There is a positive correlation between profitability and positive tones.

- H1b: There is a negative correlation between profitability and negative tone.

- H1c: There is a positive correlation between profitability and the net tone.

Aly et al. (2018) demonstrate that profitable companies disseminate more good news than unprofitable ones. Laskin (2018) reveals statistically significant differences between the strategic narratives used by top-performing and bottom-performing companies in their annual reports. Alshorman and Shanahan (2022) assert profitable companies express more positive words than unprofitable ones. CEOs of profitable companies tend to present themselves in a more positive, optimistic tone than those of leading loss-making companies. The results of these studies are consistent with signaling theory.

Merkl-Davies and Brennan (2007) posit that when companies practice impression management, they can use language in their narratives to manipulate the presentation of information, conceal lousy information, and emphasize good information. Bhana (2009) and Clatworthy and Jones (2003) assert that companies with high financial performance often release more positive than negative news than those with low economic performance. In addition, Clatworthy and Jones (2003) also revealed that managers of organizations whose performance is improving or declining prefer to blame the environment for bad news while taking in the good news. As a result, managers emphasize good financial performance while deflecting attention from their responsibility for poor financial performance.

Based on the above grounds, research hypothesis H2 is proposed as follows:

- H2: Unprofitable or loss-making firms will exhibit significant differences in positive, negative and net tones compared to profitable firms.

Like loss-making businesses, companies confronting financial difficulties and the risk of bankruptcy use narrative content to convey future messages to information users (Lohmann and Ohliger, 2020; Lopatta et al., 2017). Zhou et al. (2018) find that a positive tone significantly increases the risk of a stock crash when the narrative tone is untruthful. On the contrary, when the tone is sincere, the relationship between the narrative tone and bankruptcy risk will be reduced substantially. Leung et al. (2015) posit that companies with a higher risk of bankruptcy will confuse shareholders and investors, considering the minimal narrative information in their annual reports. Hassan et al. (2022) affirm that yearly reports’ readability/difficulty level is significantly related to bank managers’ positive/negative tone.

From the above analysis, research hypothesis H3 is proposed as follows:

- H3: Financially distressed and bankruptcy-risked companies will exhibit significant differences in positive, negative and net tones compared to non-distressed and non-bankruptcy companies.

The economic and social context also affects information disclosure and narrative content. Patelli and Pedrini (2014) conclude that the incentive to distort information strategically is low under difficult macroeconomic conditions. Instead, companies engage in communicative action aimed at dialog with shareholders through disclosure. Moreno and Jones (2022) show that the financial crisis did not wholly stop impression management activities, as positive news was always present at any stage. Therefore, they try to create the impression that they are providing a balanced view of the company’s performance rather than using impression management.

Im et al. (2021) show that hotels have actively used plausible and credible appeals in their corporate narrative on COVID-19 and streamlined their COVID-19 response strategies with defensive tactics. Bostan et al. (2022) found that reports were less prosperous in content and more challenging to read during the pandemic.

To research the difference in narrative tone on annual reports during the COVID-19 pandemic and without COVID-19, the authors propose research hypothesis H4 as follows:

- H4: Companies’ positive, negative, and net tones before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic are different.

In addition, the moderating role of bankruptcy risk and the COVID-19 pandemic in the impact of profitability on the narrative tone in annual reports is an issue that has not been explored in previous studies (Arora et al., 2022; Bostan et al., 2022; Im et al., 2021; Non and Ab Aziz, 2023). Tran et al. (2023) examined the moderating role of information asymmetry and regulatory reforms on the relationship between tone and future firm performance. The results show that the predictive power of tone on firm performance is more substantial when the level of information asymmetry is high. After the new regulation is enacted, tone conveys more information about future performance and cash flows. Dadanlar et al. (2024) examine the moderating role of CEO overconfidence in the relationship between firm performance feedback and firm sentiment. The level of CEO overconfidence will reduce the negative impact of negative performance feedback on firm sentiment, i.e., firms express more positive sentiment.

From this, the research hypothesis H5 is proposed as follows:

H5a: Bankruptcy risk moderates the relationship between profitability and positive, negative, and net tones.

H5b: COVID-19 moderates the relationship between profitability and positive, negative, and net tones.

Research design

Research data

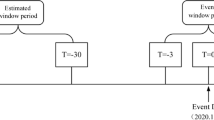

Research data was collected from companies listed on the Hanoi Stock Exchange (HNX) and Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange (HOSE) from 2015 to 2023. During this period, the Ministry of Finance of Vietnam issued Circular 155/2015/TT-BTC on information disclosure on the stock market (Ministry of Finance, 2015). Companies also experienced the stages before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the narrative content in the annual report will present in more detail the challenges, risks, and additional responses of companies in combating the pandemic.

As of December 31, 2023, the Vietnamese stock market has 698 companies listed on exchanges, including HOSE (383 companies) and HNX (315 companies) (State Securities Commission of Vietnam, 2024). After excluding financial companies (due to differences in reporting) and non-financial companies with insufficient data, the remaining 468 non-financial companies were eligible to be included in the research sample. The total number of annual reports collected from 468 companies within 9 years is 4,212, with 250,013 pages of reports to be processed.

After downloading all the companies’ annual reports in the study sample, we converted the annual report file into plain text in PDF or Microsoft Word format. Since report files are PDFs or scanned images, the study uses OCR (optical character recognition) to convert them to text format. All this processing is done with Python software and libraries.

Research model and process

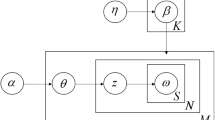

Based on background theory, research overview, and research hypotheses, we propose the following regression model:

Where:

TONEi,t: represents the narrative tone in the annual report (dependent variable) of the company i at time t. The dependent variable reflects positive, negative, and net tones in the annual report: POSTONE, NEGTONE, and NETTONE. Dependent variables related to narrative tone were measured by calculating the frequency of positive and negative terms in the annual report using Python and a natural language processing library. Because Vietnam does not yet have a dictionary of words and phrases that convey emotional nuances in the language of finance and accounting, we have compiled a list of positive and negative keywords by translating Loughran and McDonald (2011) into Vietnamese. At the same time, we also review about 200 annual reports to find and add terms with positive and negative nuances to this word list. Based on the compiled list of positive and negative phrases, using Python software, we evaluated the annual report text in the data sample to calculate the frequency of positive and negative words and phrases.

The independent variables in the model include ROA, PLOS, DIST, and COVID. Control variables include firm characteristics and financial performance (SIZE, AGE, AUD, RET, SRET, BTM, LIQ, LEV, FGRO, ACC and LENG). These control variables have been used extensively in previous studies, such as Alshorman and Shanahan (2022), Aly et al. (2018), Huang et al. (2014), Kang et al. (2018), Leung et al. (2015), Li (2010), Tran et al. (2023).

The study applies regression methods such as OLS, REM, and FEM to test hypotheses H1, H2, H3, and H4. In order to further analyze the correlation relationship, and explore the moderating role of bankruptcy risk and COVID-19 context in the relationship between profitability and narrative tone, the study uses the following two regression models (2) and (3) to test hypothesis H5:

The variables ROAi,t*DISTi,t, and ROAi,t*COVIDi,t represent the moderation effect of bankruptcy risk and COVID-19 context on the relationship between profitability and annual report tone. In the next step, the study uses the FGLS method to find efficient estimates and address the regression models’ shortcomings. Based on the selected regression model, the study discusses the results obtained.

Finally, the study applies paired bootstrap analysis and SGMM to test the robustness of the research results in model (1) and to deal with the endogeneity problem and dynamic relationships in panel data. A paired bootstrap analysis of FGLS regression for model (1) is performed with 1000 iterations. For the endogeneity problem and dynamic relationships in panel data, since the tone of the current year announcement in the annual reports of companies may be affected by the tone of the previous year, the lagged variable of the tone within three years is added to the model. Adding this lagged variable contributes to testing the stability of the relationships. Model (1) becomes as follows:

The description and measurement of all variables is provided in Table 1.

Results and discussions

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 2 displays descriptive statistics for the variables in the model. The average frequency of positive words in the annual report is 3.46%, the minimum frequency is 0.13%, and the maximum frequency is 7.63%, with a standard deviation of 0.0112. For negative words, the average frequency is 1,22%, the minimum is 0%, and the maximum is 2.85%, with a standard deviation of 0.0034. For NETTONE, the minimum value observed for the NETTONE variable is −0.28%. This negative NETTONE value indicates that the overall tone of their annual report tends to be negative because NETTONE is a metric that quantifies the difference between positive and negative tones.

For the qualitative and categorical variables in the model (AUD, DIST, PLOS, and COVID), the statistics show that in the total number of observations (4212), the frequency of occurrence of companies not audited by Big 4 auditing companies has 3009 observations, accounting for 71.4%. This data partly shows that audit quality is not high. Regarding financial risk, the frequency of companies at risk is up to 708 observations, accounting for 16.8%. Thus, for many years, most companies have faced financial risk pressure. Among the samples, there are 3959 with positive returns, accounting for 93.4%. This shows that although many companies have positive profitability, many also face financial difficulties during different periods of the research period. The proportion of observations during the COVID-19 pandemic accounted for 22.22% of the total observations.

The results of correlation analysis between variables in Table 3 show a pretty tight correlation between independent, control, and dependent variables. The results also present weak correlations between the independent and the control variables (coefficient below 0.7). Consequently, it is unlikely that multicollinearity occurs between them. To confirm whether multilinearity occurs, we continue to check the Variance inflation factor (VIF). The results of multicollinearity testing between independent variables show that the average value of VIF is 1.59, the maximum value of VIF (LEV variable) is 2.67, and the smallest value of VIF (FGRO variable) is 1.07. This result confirmed that there is no multicollinearity phenomenon between the independent variables.

We continue using White’s heteroscedasticity test and Wooldridge’s autocorrelation test. The results show a p-value of 0.000, which confirms that the OLS model exhibits heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation.

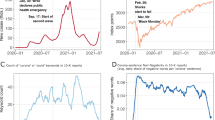

Figures 1–3 reflect the relationships between factors with positive tone (Fig. 1), negative tone (Fig. 2), and net tone (Fig. 3). These figures show that the independent variable ROA and the control variables SIZE and AUD are positive and significantly impact POSTONE and NETTONE while acting in the opposite direction on NEGTONE. The independent variable, DIST, impacts NEGTONE and NETTONE. The control variable, BTM, significantly negatively impacts POSTONE and NETTONE but influences NEGTONE in the opposite direction. The control variables, LIQ and SRET, significantly negatively impact POSTONE and NETTONE but do not affect NEGTONE. The control variable, LEV, has an inverse effect on all three narrative tones. The independent variable PLOS positively impacts NEGTONE while hurting NETTONE and does not affect POSTONE. Additionally, Figs. 1–3 shows a significant negative relationship between the control variables FGRO and LENG and the dependent variables POSTONE and NETTONE. These figures show virtually no relationship between the RET, ACC, AGE, and the dependent variables reflecting narrative tone. Meanwhile, the COVID variable affects POSTONE, NEGTONE, and NETTONE.

Regression analysis results

Multivariate regression analysis

To select the appropriate analysis model for the three dependent variables (POSTONE, NEGTONE, NETTONE), the study continues to compare the fixed effects model (FEM) and random effects model (REM) for each relevant model. The Hausman test results show that FEM is suitable for POSTONE and NETTONE models, and REM is suitable for NEGTONE research models.

Next, the results of the Wooldridge test and Wald test show that Prob > F = 0.000 and Prob > chi2 = 0.000 in all three models. This proves that all three models (POSTONE, NEGTONE, NETTONE) have autocorrelation and heterogeneous variance. Therefore, we chose the FGLS regression method to address the model’s limitations. The regression analysis results according to FGLS models for each dependent variable (POSTONE, NEGTONE, NETTONE) are summarized in Tables 4–6.

The FGLS regression results in Tables 4–6 show that three hypotheses, H1a, H1b, and H1c, are accepted. In model 1 (the POSTONE dependent variable in Table 4), there exists a significant positive relationship between profitability and positive tone in the annual report (β = 0.0066, p-value < 0.01). This implies that organizations with higher profitability tend to exhibit higher levels of positive tone. For the NEGTONE dependent variable (Model 1, Table 5), profitability has a negative influence on the negative tone in the yearly report (β = −0.0032, p-value < 0.01). This result demonstrates that enterprises with higher profitability levels tend to exhibit lower levels of negative tone in their annual reports. For the NETTONE dependent variable (Model 1, Table 6), there exists a positive relationship between profitability and net tone in the yearly report (β = 0.0099, p-value < 0.01). This finding suggests that the more profitable companies are, the more positive their annual reports are. This research result aligns with signaling and agency theory. It is consistent with the research results of Alshorman and Shanahan (2022), Aly et al. (2018), Kang et al. (2018), and Li (2010), when they found that profitability is positively related to net tone in annual reports.

Furthermore, Kang et al. (2018) and Li (2010) found that profitability is positively associated with the net tone of annual reports. Aly et al. (2018) discovered that profitability has a positive relationship with excellent and net news disclosure but a negative relationship with bad news disclosure on annual reports. Alshorman and Shanahan (2022) demonstrate that profitability positively affects the positive and net tone of CEOs’ letters but has a negative effect on the negative tone. Disclosure of managerial tone contributes to sound decision-making by overcoming information asymmetry between managers and information users. Furthermore, promoting managers’ success increases the confidence of investors and other information users. Naturally, managers of highly profitable companies will want to share that information and have no intention of hiding their good performance.

The empirical evidence supports hypothesis H2 (Unprofitable or loss-making companies will exhibit significant differences in negative tone and net tone compared to profitable companies). The regression results show that in model 1 (Tables 5 and 6), the PLOS variable is statistically significant at the 1% level. It demonstrates that unprofitable or loss-making companies use more negative and less explicit net tones in their disclosures than profitable companies. The value of the PLOS variable in model 1 (Table 4) is not statistically significant (p-value > 0.1). This finding demonstrates no apparent difference in positive tone statements between unprofitable and profitable organizations. The annual reports of unprofitable or loss-making companies do not differ in positive tone. Instead, they use a more negative tone and a less explicit net tone than profitable firms.

This finding is supported by studies by Bhana (2009) and Martikainen et al. (2023), who posit that firms with negative profitability present a more negative tone than firms with positive profitability. This provides further evidence to users about managers’ behavior in disclosing information. Our finding also differs from Bhana (2009), who revealed that companies with improving business performance reported more good news than companies with declining business performance. Managers of companies with poor profitability try to use the same optimistic tone as companies with good profitability to create a favorable impression on information users and hide their poor financial results.

Regarding the impact of DIST, the regression results of model 1 (Tables 5 and 6) demonstrate a negative tone and net tone difference between companies with bankruptcy risk and companies without bankruptcy risk (at a 1% significance level). However, in the regression results of model 1 (Table 4), there is no empirical evidence of a positive tone difference between companies facing bankruptcy risk and those not. Therefore, hypothesis H3 is accepted. The findings suggest that financially distressed companies report a more negative tone and less net tone than companies not at risk of bankruptcy.

These findings indicate that companies facing bankruptcy risk tend to exhibit a more negative tone in their annual reports than companies that are not at bankruptcy risk. This result is similar to Boo and Simnett (2002) and Gandhi et al.(2019). Boo and Simnett (2002) asserts that when facing financial difficulties, companies that do not disclose management opinions are more likely to fail than companies that disclose management optimism. Gandhi et al.(2019) confirm that managers of companies under financial pressure often use a higher proportion of negative words in annual reports to describe the company’s economic situation. Our findings suggest that financially distressed firms do not employ impression management to mitigate their current situation. These companies convey information that accurately reflects their present circumstances, fostering investor trust in their disclosures.

Regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, the empirical results in Model 1 (Tables 4–6) show that pre-COVID-19 firms exhibit fewer positive and negative tones but more net tones than COVID-19 firms. The β coefficient of the impact of pre-COVID-19 on positive tone is −0.0005 with a significance level of 5%, the β coefficient of the effect of pre-COVID-19 on negative tone is −0.0011 with a significance level of 1%, and the β coefficient of the impact of pre-COVID-19 on net tone is 0.0004 with a significance level of 10%. In addition, during the COVID-19 pandemic period under control, companies announced more positive tone and net tone and less negative tone than during the pandemic outbreak period. The β coefficient of the impact of post-COVID-19 on positive tone and net tone is 0.0005 and 0.0007, respectively, while the β coefficient of the effect of post-COVID-19 on negative tone is −0.0002 with significance levels of 5% and 1%. Thus, hypothesis H4 is accepted. The empirical results also show that during the COVID-19 pandemic, companies used more positive and negative tones than before the pandemic. After the COVID-19 pandemic was well controlled, managers used more positive signals and fewer negative signals than during the pandemic outbreak. Thus, during the COVID-19 pandemic, companies tried to show stakeholders the company’s positive aspects, but they still communicated their difficult situation through a more negative tone. When the pandemic situation stabilized, managers expressed the change in the context in a more positive way. This fact shows that companies did not use impression management in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Managers still accurately conveyed the company’s current situation in the problematic context of the pandemic. This result is similar to Moreno and Jones (2022) and Patelli and Pedrini (2014). In difficult macroeconomic situations, companies try not to use impression management openly and, to a certain extent, want to make clear the crisis’s impact on business performance.

According to the NEGTONE model (Table 5), RET is negatively related to negative tone at the 10% significance level. Meanwhile, no evidence indicates that RET impacts annual reports’ positive and net tone. This result is similar to the study of Huang et al. (2014), where they failed to find evidence of a relationship between RET and narrative tone. This result contrasts Li’s (2010) research, where he stresses that RET has a positive relationship with narrative tone.

Regarding the impact of SRET, SRET hurts positive tone at a 5% significance level (Table 4) and has a positive effect on net tone at a 1% significance level (Table 6). No statistical evidence in Table 5 has been found to suggest that SRET impacts negative tone. This is entirely different from the research results of Huang et al. (2014), where they found a positive relationship between SRET and narrative tone. This result is also distinct from the study of Kang et al. (2018), which found a negative relationship between stock return volatility and narrative tone.

SIZE has a positive impact on positive tone (Table 4) and net tone (Table 6) and a negative impact on negative tone (Table 5) on annual reports at 1% significance. This implies that larger-sized organizations tend to express a greater degree of positivity and a lesser degree of negativity in their yearly reports. This finding is supported by the research of Pham and Do (2015), who found that the larger the company’s size, the better the information disclosure level. However, this finding contradicts the studies of Huang et al. (2014), Kang et al. (2018), and Li (2010), when they realized that as company size increased, the level of narrative tone in the annual report decreased. This result is also not similar to the study of Aly et al. (2018), where they found no relationship between company size and emotional disclosure.

The regression results also show a negative impact of BTM on positive tone (Table 4) and net tone (Table 6) at the 1% significance level. This is similar to the research results of Huang et al. (2014) and Kang et al. (2018), who confirm that firms with higher book-to-market value ratios have lower narrative tones. However, this result contradicts the study of Li (2010), who found a positive relationship between the market-to-book ratio and narrative tone.

The study results found no impact of AGE on positive, negative, and net tone in annual reports. This result is supported by Aly et al. (2018) and Huang et al. (2014). Their studies found no correlation between AGE and narrative tone. This result also contrasts with Kang et al. (2018) and Li (2010), who have empirical evidence that the narrative tone is increased in companies with a long operating period compared to other companies. The research results differ from the studies of Alshorman and Shanahan (2022), who found evidence that firm age is positively related to the CEO’s negative tone.

Regarding LIQ, the company’s liquidity negatively impacts both the positive tone and the net tone at the 1% significance level. However, there is no empirical evidence for the impact of LIQ on negative tone. This result aligns with the findings of Aly et al. (2018), which indicate that liquidity negatively affects the narrative tone of annual reports. However, this result differs from Fisher et al. (2019), who found no empirical evidence on the relationship between liquidity and emotional tone.

The regression results clearly show the relationship between LEV and narrative tone. Accordingly, LEV has a negative relationship at the 1% significance level with positive tone (Table 4), negative tone (Table 5), and net tone (Table 6). It can be said that companies with high financial leverage tend to be less vocal in their annual reports. This result receives support from the study of Aly et al. (2018), who found a negative effect of financial leverage on the narrative tone. However, this contradicts the research results of Alshorman and Shanahan (2022), who found that financial leverage positively impacts the narrative tone of CEOs’ letters. This result is also not similar to Fisher et al.’s (2019) study, which found no correlation between financial leverage and emotional tone.

Research results show that FGRO has a negative impact on positive tone and net tone at the 1% significance level and does not affect negative tone. This result is similar to that of Aly et al. (2018), which confirmed decreased narrative tone in high-growth companies. However, this result differs from the findings of Alshorman and Shanahan (2022), who found no effect of growth rate on narrative tone.

AUD also has a particular influence on the narrative tone. The regression results in Tables 4 and 6 show that the variable AUD is statistically significant at 1%. That proves that companies audited by Big4 companies publish more positive and net tone than those audited by others. In Vietnam, companies audited by the Big 4 are usually listed as large-scale companies with significant influence on the entire economy. Therefore, managers in these companies pay more attention to the narrative tone used in annual reports. Alshorman and Shanahan (2022) proved this result in their study, which found that companies audited by Big4 have a higher level of positive tone disclosure than companies not audited by Big4. However, this result is not similar to the studies of Aly et al. (2018) and Leung et al. (2015), where they found no relationship between audit quality and emotional tone.

Regarding the impact of ACC on narrative tone, Table 4 found no relationship between them across all three models. This result shows that accruals do not affect narrative tone. This result differs from Li (2010), who found that discretionary accruals negatively affect narrative tone. It is also different from the study by Abou-El-Sood and El-Sayed (2022), who found that the level of discretionary accruals was positively related to the disclosure of unusual tones.

Finally, at the 1% significance level, the LENG is negatively related to positive tone (Table 4) and net tone (Table 6) but is positively associated with negative tone (Table 5). Therefore, as the length of the annual report increases, the positive and net tones will decrease, and the negative tone will improve. This result implies that company managers tend to convey messages explaining and clarifying the causes of unfavorable business situations and unsatisfactory business performance.

Analysis of the moderating impact of bankruptcy risk

Model (2) results in Tables 4–6 demonstrate the moderating role of bankruptcy risk on the relationship between profitability and narrative tone in the annual report. The results of interest are the interaction variable DIST = 2*ROA, i.e. the interaction between the dummy variable for DIST = 2 (the company’s bankruptcy risk status) and profitability. The moderating role of bankruptcy risk (DIST) is only statistically significant for the relationship between profitability and negative tone with coefficient β = −0.0032 and p-value < 0.05. Thus, when companies are at risk of bankruptcy, the negative relationship between profitability and negative tone becomes more pronounced. In other words, when the firm faces bankruptcy risk (DIST = 2), the decline in profitability is associated with a significant increase in negative tone due to the moderating effect of high bankruptcy risk on the relationship between profitability and negative tone in annual reports. This may confirm that firms do not choose impression management when facing financial difficulties. In this situation, firms convey a more negative tone to reflect the situation. Thus, hypothesis H5a is rejected.

Analysis of the moderating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

The results of Model (3) in Tables 4–6 indicate that the interaction variable COVID*ROA, which represents the combined impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and profitability, has a statistically insignificant effect on all three dependent variables POSTONE, NEGTONE and NETTONE. This finding suggests that, although the direct impact of COVID and ROA variables on POSTONE, NEGTONE and NETTONE is statistically significant, the moderating effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the relationship between profitability and narrative tone is insignificant. It can be said that the impact of profitability on the narrative tone in the annual report is not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, hypothesis H5b is rejected.

Paired bootstrap and SGMM analysis

The study implemented bootstrapping (pairs bootstrap) and SGMM to test the robustness of the effects in the FGLS model.

The bootstrap results with 1000 iterations for the FGLS regression estimates for the original model are reflected in Tables 4–6. The bootstrap standard error (shown in parentheses) is relatively small (the most significant standard error is 0.0086). Because the bootstrap standard error is calculated from the standard deviation of the estimates for each iteration, the regression coefficient estimates are highly reliable, and the original data sample is of good quality. This result confirms that not many fluctuations or outliers affect the estimates. Moreover, the estimates from the bootstrap samples are distributed narrowly and concentrated around the mean value. The findings noted statistically significant effects of the variables in the model on positive, negative, and net tone.

The results of endogenous treatment and verification of the sustainability of the research model by SGMM regression method are reflected in Tables 4–6 (column SGMM). The findings show that the lagged variables of the last two years of POSTONE, NEGTONE, and NETTONE strongly correlate with these dependent variables. Specifically, the lagged variables of positive, negative, and net tone in the last two years are positively correlated with the current year’s positive, negative, and net tone at the significance level of 1% and 5%, respectively. However, the three-year lagged variables have weak or no impact on the current year’s tone. Regarding profitability, ROA maintains the direction of effects on tone as in FGLS regression. ROA has a positive impact on positive and net tone at the significance level of 5% and a negative impact on negative tone at the significance level of 10%. For the COVID variable, the direction of the effect of COVID-19 on TONE remains stable compared to the FGLS regression, but the statistical significance decreases. This suggests that there is not yet a solid basis for confirming the impact of the pandemic on the narrative tone in annual reports. However, the SGMM regression results show that the PLOS and DIST variables are not statistically significant in their impact on narrative tone. The FGLS regression results also show that the PLOS and DIST variables affect narrative tone at a certain level of statistical significance. This finding indicates that the tone of the annual report is positively influenced by the tone of the two consecutive years.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study demonstrates that profitability has a positive impact on positive and net tones in annual reports and a negative impact on negative tones. The more profitable a company is, the more positive tone and less negative tone its yearly report contains. The study also determined that companies that are losing money tend to use more negative tones than companies that are making a profit. This provides further evidence for the behavior of managers who provide information to assist information users in making decisions. However, this study finds no statistical evidence of a difference between positive attitudes in the annual reports of low- and high-profit companies. Managers of companies with poor profitability attempt to use the same upbeat tone as companies with good profitability to create a favorable impression on information users.

The findings of this study provide further evidence in support of impression management theory and agency theory. Firms facing financial difficulties adopt a less positive net tone and a more negative tone. This suggests that firms are attempting to convey some of their current distress. Based on agency theory, this result indicates that managers are trying to bolster the confidence of existing and potential investors. Furthermore, statistical evidence suggests a moderating role of bankruptcy risk on the relationship between profitability and negative tone. That is, when firms risk bankruptcy, profitability decreases, and negative tone increases in annual reports. This finding supports the proposition that managers disclose their company’s circumstances honestly when companies face financial difficulties.

The empirical results also provide evidence for the signaling theory. Companies during the COVID-19 pandemic tend to use a more positive tone than pre-COVID-19. In the post-COVID-19 period, managers expressed more positive tones and less negative tones. This narrative tone is intended to impress and increase investor confidence in the company. Furthermore, the results also showed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, companies expressed a more negative tone than pre-COVID-19. They want to use narrative content in the annual report to convey information about the general difficult context caused by the pandemic. This finding demonstrates that the relationship between profitability and narrative tone is not affected by the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study has implications for investors and information users regarding managers’ disclosure of information through the narrative tone used in annual reports. Managers can use the narrative tone to convey the company’s profitability and financial health. On the other hand, information users can use a narrative tone to evaluate a company’s profitability and current and future financial status. However, managers can strategically adjust the narrative tone of communication to conceal unfavorable information. Therefore, investors and information users should carefully evaluate information sources before making decisions. Managers can choose several methods of communicating information to users based on their own goals. The decision between communicating and manipulating information will affect the trust of investors and other information users. People often advocate transparent disclosure of information by regulators to minimize the occurrence of information asymmetry in the market. However, managers must acknowledge the risk of losing investors’ trust and confidence if they choose to hide information.

This study has contributed to the theory and practice of accounting narrative research in Vietnam and internationally. It suggests a new direction for accounting research in Vietnam. However, the study still has certain limitations. Firstly, the limitation of the research sample. The research sample is only limited to several non-financial companies listed in Vietnam. It has not been expanded to countries in the emerging economic group in the region and the world. Therefore, the representativeness of the research results is not high. Secondly, the limitation of the approach. This study only focuses on the narrative tone in annual reports and has not mentioned other issues related to the narrative content. We recognize several potential opportunities for further research. Future studies investigate the predictive power of narrative tone about profitability and explore additional aspects of the narrative content in the annual report (readability, rhetorical analysis, story-telling, etc.). With the growing popularity of social media and AI-based text analysis techniques, future studies could expand the sample size and apply modern analysis methods instead of traditional methods.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abou-El-Sood H, El-Sayed D (2022) Abnormal disclosure tone, earnings management and earnings quality. J Appl Account Res 23(2):402–433. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-07-2020-0139

Adelberg AH (1979) Narrative disclosures contained in financial reports: means of communication or manipulation? Account Bus Res 9(35):179–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.1979.9729157

Alshorman SAA, Shanahan M (2022) The voice of profit: exploring the tone of Australian CEO’s letters to shareholders after the global financial crisis. Corp Commun Int J 27(1):127–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-12-2020-0169

Aly D, El-Halaby S, Hussainey K (2018) Tone disclosure and financial performance: evidence from Egypt. Account Res J 31(1):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-09-2016-0123

Arora S, Debesay J, Eslen-Ziya H (2022) Persuasive narrative during the COVID-19 pandemic: Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg’s posts on Facebook. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01051-5

Barth ME (2006) Including estimates of the future in today’s financial statements. Account Horiz 20(3):271–285. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2006.20.3.271

Beattie V (2014) Accounting narratives and the narrative turn in accounting research: Issues, theory, methodology, methods and a research framework. Br Account Rev 46(2):111–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2014.05.001

Beattie V, McInnes B, Fearnley S (2004) A methodology for analysing and evaluating narratives in annual reports: a comprehensive descriptive profile and metrics for disclosure quality attributes. Account Forum 28(3):205–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2004.07.001

Bhana N (2009) The chairman’s statements and annual reports: are they reporting the same company performance to investors? Invest Anal J 38(70):32–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10293523.2009.11082513

Bochkay K, Brown SV, Leone AJ, Tucker JW (2023) Textual analysis in accounting: what’s next? Contemp Account Res 40(2):765–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12825

Boo E, Simnett R (2002) The information content of management’s prospective comments in financially distressed companies: a note. Abacus 38(2):280–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6281.00109

Bostan I, Bunget O-C, Dumitrescu A-C, Burca V, Domil A, Mates D, Bogdan O (2022) Corporate disclosures in pandemic times. the annual and interim reports case. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 58(10):2910–2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2021.2014316

Brown SV, Tucker JW (2011) Large‐sample evidence on firms’ year‐over‐year MD&A modifications. J Account Res 49(2):309–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2010.00396.x

Buzgurescu OLP, Elena N (2020) Bankruptcy risk prediction in assuring the financial performance of Romanian industrial companies. In: Buzgurescu OLP, Elena N (eds.) Contemporary issues in business economics and finance. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.pp. 19–28 https://doi.org/10.1108/S1569-375920200000104003

Cherry C, Mohamed W, Brahmbhatt Y (2023) Using FinBERT as a refined approach to measuring impression management in corporate reports during a crisis. Communicare J Commun Stud Afr 42(1):64–80. https://doi.org/10.36615/jcsa.v42i1.2318

Clatworthy M, Jones MJ (2003) Financial reporting of good news and bad news: evidence from accounting narratives. Account Bus Res 33(3):171–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2003.9729645

Czarniawska B (2017) An emergence of narrative approaches in social sciences and in accounting research. In: Hoque Z, Parker LD, ovaleski MA, Haynes K (eds.). The Routledge companion to qualitative accounting research methods. 1st edn. Routledge. pp. 16–20

Dadanlar HH, Vaswani MM, Al-Shammari M, Banerjee SN (2024) Firm performance feedback and organizational impression management: The moderating role of CEO overconfidence. J Manag Organ 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2024.8

Fisher R, van Staden CJ, Richards G (2019) Watch that tone: an investigation of the use and stylistic consequences of tone in corporate accountability disclosures. Account Audit Account J 33(1):77–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-10-2016-2745

Fontanella L, Chulvi B, Ignazzi E, Sarra A, Tontodimamma A (2024) How do we study misogyny in the digital age? A systematic literature review using a computational linguistic approach. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(478):478. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02978-7

Gandhi P, Loughran T, McDonald B (2019) Using annual report sentiment as a proxy for financial distress in U.S. banks. J Behav Financ 20(4):424–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2019.1553176

Goffman E (1959) The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday & Company

Hajek P, Olej V, Myskova R (2014) Forecasting corporate financial performance using sentiment in annual reports for stakeholders’ decision-making. Technol Econ Dev Econ 20(4):721–738. https://doi.org/10.3846/20294913.2014.979456

Hassan MK, Abu-Abbas B, Kamel H (2022) Tone, readability and financial risk: the case of GCC banks. J Account Emerg Econ 12(4):716–740. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-06-2021-0192

Huang AH, Wang H, Yang Y (2023) FinBERT: a large language model for extracting information from financial text*. Contemp Account Res 40(2):806–841. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12832

Huang AH, Zang AY, Zheng R (2014) Evidence on the information content of text in analyst reports. Account Rev 89(6):2151–2180. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50833

Huang X, Teoh SH, Zhang Y (2014) Tone management. Account Rev 89(3):1083–1113. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50684

Im J, Kim H, Miao L (2021) CEO letters: hospitality corporate narratives during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Hospit Manag 92:102701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102701

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3(4):305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

Kang T, Park D-H, Han I (2018) Beyond the numbers: the effect of 10-K tone on firms’ performance predictions using text analytics. Telemat Inform 35(2):370–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.12.014

Laskin AV (2018) The narrative strategies of winners and losers: analyzing annual reports of publicly traded corporations. Int J Bus Commun 55(3):338–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488418780221

Leung S, Parker L, Courtis J (2015) Impression management through minimal narrative disclosure in annual reports. Br Account Rev 47(3):275–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2015.04.002

Li F (2010) The information content of forward‐looking statements in corporate filings—a naïve bayesian machine learning approach. J Account Res 48(5):1049–1102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2010.00382.x

Lohmann C, Ohliger T (2020) Bankruptcy prediction and the discriminatory power of annual reports: empirical evidence from financially distressed German companies. J Bus Econ 90(1):137–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-019-00938-1

Lopatta K, Gloger MA, Jaeschke R (2017) Can language predict bankruptcy? The explanatory power of tone in 10‐K filings. Account Perspect 16(4):315–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3838.12150

Loughran T, McDonald B (2011) When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10‐Ks. J Financ 66(1):35–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01625.x

Martikainen M, Miihkinen A, Watson L (2023) Board characteristics and negative disclosure tone. J Account Lit 45(1):100–129. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAL-03-2022-0033

Merkl-Davies DM, Brennan N (2007) Discretionary disclosure strategies in corporate narratives: incremental information or impression management? J Account Lit 27:116–196

Ministry of Finance (2015) Circular on guidelines for information disclosure on securities market (155/2015/TT-BTC). Government Electronic Information Portal; https://vanban.chinhphu.vn/default.aspx?pageid=27160&docid=182551

Moreno A, Jones MJ (2022) Impression management in corporate annual reports during the global financial crisis. Eur Manag J 40(4):503–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2021.08.007

Morris RD (1987) Signalling, agency theory and accounting policy choice. Account Bus Res 18(69):47–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.1987.9729347

Mućko P (2021) Sentiment analysis of CSR disclosures in annual reports of EU companies. Procedia Comput Sci 192:3351–3359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.09.108

Naegele KD, Goffman E (1956) The presentation of self in everyday life. Am Sociol Rev 21(5):631–632. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089106

Non N, Ab Aziz N (2023) An exploratory study that uses textual analysis to examine the financial reporting sentiments during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Financ Report Account 21(4):895–915. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-10-2022-0364

Patelli L, Pedrini M (2014) Is the optimism in CEO’s letters to shareholders sincere? Impression management versus communicative action during the economic crisis. J Bus Ethics 124(1):19–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1855-3

Pham DH, Do THL (2015) Factors influencing the voluntary disclosure of Vietnamese listed companies. J Modern Account Audit 11(12). https://doi.org/10.17265/1548-6583/2015.12.004

Pham TTC (2019, December 5). The quality of annual reports will be better if… Stock Investment. https://www.tinnhanhchungkhoan.vn/chat-luong-bao-cao-thuong-nien-se-tot-hon-neu-post226272.html

Qian Y, Sun Y (2021) The correlation between annual reports’ narratives and business performance: a retrospective analysis. SAGE Open 11(3):215824402110321. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211032198

Rutherford BA (2005) Genre analysis of corporate annual report narratives: a corpus linguistics-based approach. J Bus Commun 42(4):349–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943605279244

Rutherford BA (2018) Narrating the narrative turn in narrative accounting research: scholarly knowledge development or flat science? Meditari Account Res 26(1):13–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-04-2017-0139

Shehata NF (2014) Theories and determinants of voluntary disclosure. Account Financ Res 3(1):18–26. https://doi.org/10.5430/afr.v3n1p18

Smith M, Dong Y, Ren Y (2011) The predictive ability of corporate narrative disclosures: Australian evidence. Asian Rev Account 19(2):157–170. https://doi.org/10.1108/13217341111181087

State Securities Commission of Vietnam (2024, January 11) List of public companies as of December 31, 2023 (excluding securities companies and fund management companies). State Securities Commission of Vietnam Portal. https://ssc.gov.vn/webcenter/portal/ssc/pages_r/l/chitit?dDocName=APPSSCGOVVN1620142747

Tran LTH, Tu TTK, Nguyen TTH, Nguyen HTL, Vo XV (2023) Annual report narrative disclosures, information asymmetry and future firm performance: evidence from Vietnam. Int J Emerg Mark 18(2):351–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-08-2020-0925

Verrecchia RE (1983) Discretionary disclosure. J Account Econ 5:179–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(83)90011-3

Vietnam Institute of Directors—VIOD (2023, December 12) Practices and good practices in annual reporting. Stock Investment. https://www.tinnhanhchungkhoan.vn/thuc-tien-va-thong-le-tot-ve-bao-cao-thuong-nien-post335605.html

Williams T, Edwards M, Angus-Leppan T, Benn S (2021) Making sense of sustainability work: a narrative approach. Aust J Manag 46(4):740–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896220978447

Yekini LS, Wisniewski TP, Millo Y (2016) Market reaction to the positiveness of annual report narratives. Br Account Rev 48(4):415–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2015.12.001

Zhou B, Zhang C, Zeng Q (2018) Does the rhetoric always hide bad intention: annual report’s tone and stock crash risk. China J Account Stud 6(2):178–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/21697213.2018.1522038

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors listed have significantly contributed to this article’s development and writing. The authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Le, B.T.H., Nguyen, C.V. Studying the impact of profitability, bankruptcy risk, and pandemic on narrative tone in annual reports in an emerging market in the East. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1441 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03980-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03980-9