3. Results

Data analyses were carried out in jamovi 2. To check our experimental manipulation, we ran three Independent Sample

t-Tests to assess differences between the two experimental groups according to the perceived moral severity of the recalled PMIE, the perceived role of witness and, respectively, perpetrator played by the participant. Results showed no differences according to moral severity, as well as significant differences in terms of the two roles, supporting the validity of the experimental manipulation (

Table A1).

To verify participant randomization in the two experimental groups, we assessed with Independent Sample

t-Tests and Chi-Square Tests of Association differences according to participants’ age, sex, education, work experience, weekly hours of work, marital status and general need-satisfaction at work. We found no significant differences, except for marital status, for which there were more single participants in the self-PMIE group and more married participants in the other-PMIE group (see

Table 1 and

Table A1). Consequently, this variable was treated as an independent variable.

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics and Differences between Them According to Outcome Variables

Socio-demographic differences in outcomes of interest were assessed with Welch’s Independent Sample

t-Tests and One-Way ANOVAs, due to violations of the assumption of equal variances and unequal sample sizes (

Table A2). For this purpose, we stratified “age” and “work experience”.

Participants with less work experience (i.e., less than or equal to 10 years) experienced significantly less

general basic psychological need-satisfaction at work than participants with more work experience (i.e., between 11 and 36 years). Similarly, younger participants (i.e., 21–30 years old) experienced less general basic psychological need-satisfaction at work as compared to participants aged from 31–40 years old (

t(216) = −7.2,

p < 0.001) and as compared to participants aged from 41–57 years old (

t(255) = −7.37,

p < 0.001). Participants who worked 36 h a week experienced more general basic psychological need-satisfaction than both participants who worked 48 h a week (

t(329) = 6.26,

p < 0.001) and participants who worked 60 h a week (

t(124.8) = 5.88,

p < 0.001) (

Table A2).

Participants who were single experienced significantly more

burnout as compared to their married counterparts, similar to participants with less work experience, who reported more burnout than participants with more work experience. This trend was mirrored by the effects of participants’ age, with those aged from 21 to 30 reporting more burnout than those aged from 31 to 40 (

t(269) = 9.26,

p < 0.001) and more than those aged from 41 to 57 (

t(240) = 5.62,

p < 0.001). Participants who worked 36 h a week reported less burnout than participants who worked 48 h a week (

t(248) = −8.33,

p < 0.001) and less than participants who worked 60 h a week (

t(140) = −7.01,

p < 0.001). We also looked at differences according to the three dimensions of burnout (EE, DP, PA) and found the same pattern of results for EE, but no significant effect of marital status for PA and DP (

Table A2).

Turnover intentions were stronger for single participants as compared to married participants, and weaker for participants who worked 36 h a week as compared to participants who worked 48 h a week (

t(255) = −2.68,

p = 0.021) and as compared to those who worked 48 h a week (

t(166) = −2.955,

p = 0.010) (

Table A2).

Finally, to explore differences in outcomes of interest according to participants’ specialty, we ran a series of One-Way ANOVAs, after removing the one participant we had from the Dentistry specialization, to have sufficient observations for every category of the grouping variable. Since the assumptions about homogeneity of variances and normality of the distributions were met, we used Fisher’s coefficients with Tukey post-hoc tests. We only found significant differences in burnout between different specialties (F(14, 447) = 1.82, p = 0.033), with no significant differences in post-hoc tests. Given the unequal group sizes and their high number in relation to the total sample size, this result should be interpreted with caution.

3.2. Correlational Analyses

Pearson’s correlations were computed to assess the associations between the outcome variables and the characteristics of the memories (

Table A3). Significant positive associations were found between participants’ turnover intentions and frequency of voluntary and involuntary retrieval, emotional intensity and valence, vividness, visual detail, sense of reliving, importance and centrality to the self of memories of PMIEs, and, respectively, both burnout and turnover intentions. In contrast, the higher the turnover intentions and the higher the burnout, the lower the general basic psychological need-satisfaction at work, and the lower the basic psychological need-satisfaction during the recalled PMIE, a trend registered for autonomy, competence and relatedness. As expected, significant correlations were found between the majority of the phenomenological characteristics of the PMIE memories, as well as between them and basic psychological need-satisfaction during the recalled PMIE (

Table A3). Participants’ sex was significantly correlated with relatedness-thwarting (

r = 0.104,

p = 0.026) only, with men’s memories of PMIEs being associated with more relatedness-thwarting than females.

3.3. The Influence of Basic Psychological Need-Satisfaction in Memories of PMIEs on Nurses’ Burnout and Turnover Intentions

To test H1 and H2, we conducted a series of hierarchical regressions (

Table 2). Correlational analyses showed that age and work experience were highly associated (

r = 0.81,

p < 0.001); to avoid collinearity violations, we only kept “age” in the analyses, the demographic with the highest correlations with burnout (

r = −0.22,

p < 0.001) and turnover intentions (

r = −0.094,

p = 0.043) [

25].

Results have confirmed the unique contribution of basic psychological need-thwarting during the recalled PMIE to explaining additional variance for both burnout and turnover intentions, when controlling for socio-demographic characteristics and, respectively, for other phenomenological characteristics of the memories. Prior to adding basic psychological need-thwarting during the recalled PMIE to the model, weekly hours at work, age, marital status and general need-satisfaction at work were significantly related to burnout, of which only weekly hours and general need-satisfaction at work remained significant in Step 2. Turnover intentions were significantly predicted by marital status and general need satisfaction at work, of which only the latter remained significant upon adding basic psychological need-thwarting during the recalled PMIE to the model.

For phenomenological characteristics, burnout was significantly predicted by involuntary retrieval, emotional intensity and importance to the self before adding basic psychological need-thwarting during the recalled PMIE to the model, when only emotional intensity remained a significant predictor. Turnover intentions were significantly predicted by involuntary retrieval and emotional intensity before adding basic psychological need-thwarting during the recalled PMIE to the model, when both relationships were rendered insignificant.

3.4. Differences in Phenomenological Characteristics of Memories and Psycho-Social Work Outcomes According to the Type of PMIE Recalled (Self- vs. Other-PMIE)

To test H3 and H4, and to explore other differences in phenomenological characteristics according to the type of PMIE recalled (self- vs. other-PMIE), we conducted a series of Independent Sample

t-Tests (See

Table 3). Autonomy and competence were more thwarted in memories of self-PMIEs compared to memories of other-PMIEs, whereas relatedness is more thwarted in memories of other-PMIEs rather than self-PMIEs. However, the means of the three basic psychological needs were below zero for both memories of self- and other-PMIEs, indicating that they are need-thwarting memories [

25,

27,

32]. Memories of self-PMIEs were associated with higher burnout than memories of other-PMIEs, with significant differences for all its three dimensions: EE, DP and PA.

Memories of self-PMIEs were experienced in more visual detail and as more vivid, emotionally negative and intense, important and central to the self, being retrieved more often involuntarily and voluntarily and associated with a greater sense of reliving as compared to memories of other-PMIEs. Additionally, participants rated both types of memories as rather important and central to their selves (means between 4.77 and 5.24 out of a possible 7—indicating moderately to considerably important).

3.5. The Mediating Role of Basic Need-Satisfaction in the Relationship between Type of PMIE and Work Outcomes

To test H4, we conducted two mediation analyses in jamovi, module jAMM, with the type of memory (self- vs. other-PMIE) as the independent variable, the three basic psychological needs as mediators, and burnout and turnover intentions as dependent variables (

Table 4). Results showed that basic need-satisfaction fully mediated the association between the type of memory and turnover intentions, with significant indirect effects for autonomy and relatedness. Thus, autonomy and competence were more thwarted, and relatedness was more satisfied in memories of self-PMIEs than in memories of other-PMIEs. The more thwarted the needs of autonomy and relatedness, the higher the turnover intentions. This suggests that the main differences between the two types of memories regarding nurses’ intentions might be explained by the differences in the thwarting of autonomy and relatedness.

For burnout, we found that its relationship with the type of memory (self- vs. other-PMIE) was partially mediated by relatedness and competence. Thus, autonomy and competence were more thwarted, and relatedness was more satisfied in memories of self-PMIEs than in memories of other-PMIEs. The more thwarted the needs of competence and relatedness, the higher the burnout. This indicates that the main differences between the effects of the two types of memories on burnout reside in the extent to which the needs for relatedness and competence were thwarted (

Table 4). Supplementary mediation analyses indicated that competence and relatedness partially mediated the relationship between the type of memory and EE, and that the relationships between the type of memory, DP and PA were partially mediated by relatedness (

Table A4). This would suggest that the differences in personal accomplishment, depersonalization and emotional exhaustion between memories of self- and other-PMIEs were associated with differences in relatedness and in competence-thwarting, with the latter being true only for emotional exhaustion.

4. Discussion

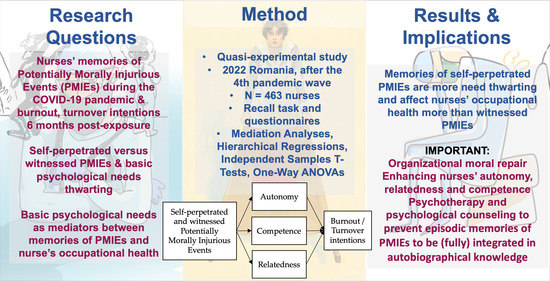

This study aimed to investigate the effects of nurses’ episodic memories of PMIEs during the COVID-19 pandemic on their burnout and turnover intentions, according to basic psychological need-thwarting, phenomenological characteristics and socio-demographic characteristics. Using a quasi-experimental design, we differentiated between memories of self- and other-PMIEs in our analyses, while also clearly delineating between exposure to PMIEs and moral injury, in line with past recommendations [

5,

12,

13]. Overall, our results suggest that nurses’ exposure to both self- and other-PMIEs may still have a detrimental impact on their occupational health after at least six months, mainly according to the degree of basic psychological need-thwarting associated with their episodic memories of the events.

Autobiographical episodic memories are the building blocks for our identity [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Though not all episodic memories are retained in autobiographical knowledge [

18], we remember those that best illustrate who we are (i.e., our conceptual selves). When episodic memories severely contradict our autobiographical knowledge and our identities, we tend to forget or distort them to better fit our narratives about ourselves and our lives [

18]. However, not all conflicting episodic memories are forgotten or distorted by the conceptual self [

25]; some, especially the more traumatic ones, are retained [

29], either to be eventually integrated into autobiographical knowledge [

79,

80], or because they are intimately related with our goal systems [

16,

28]. Thus, they have the capacity of directing our behavior [

81,

82] and affecting our psycho-social health and functioning [

25,

26,

27,

30,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Our findings suggest that nurses’ memories of self- and other-PMIEs may be closely linked to the three macroscopic, innate goals of human beings (i.e., autonomy, competence, relatedness) [

36] and, thus, be retained in long-term memory, potentially for subsequent integration, since they were rated as moderately to considerably important and central to the self [

25]. At any rate, they were uniquely associated with nurses’ burnout and turnover intentions, indicating that they may function as behavior guides and affect nurses’ occupational health.

If the memories of PMIEs having occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic are to be integrated in nurses’ autobiographical knowledge by nurses, this would dramatically change their work identities [

25,

27], with negative consequences on their psychological health and on the healthcare system. Previous studies found that a high rate of nurses and other healthcare providers have been exposed to PMIEs during this pandemic e.g., [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

47,

48,

49,

50,

54,

56,

57,

62,

64,

68]. Moral values and work ethics are central to the identity of nurses, guiding them in their professional activity and providing meaning to their work [

21]. Should these identities be modified by their episodic memories of PMIEs, they would see themselves as capable of perpetrating or idly witnessing immoral acts in relation to patients [

16,

18]. Given that self-concept regulates behavior, they could repeat these actions in the future in more or less similar circumstances [

11], which would have deleterious consequences on patientcare. Alienation from fellow providers and their occupation may also ensue, especially for other-PMIEs, which severely thwarted their need for relatedness, affecting the organizational climate [

83,

84]. Finally, given the incoherence between their current self-representations and beliefs and their memories of PMIEs, the integration of the latter could lead to greater posttraumatic symptoms [

85].

Our findings support an ongoing attempt at integrating memories of PMIEs into autobiographical knowledge, with participants reporting moderate to considerable voluntary and involuntary retrieval of memories of PMIEs, reliving, vividness, visual detail, importance and centrality to the self [

25]. These phenomenological characteristics were significantly more heightened for memories of self-PMIEs than for memories of other-PMIEs, differences not studied so far, but which could be attributed to the omission bias [

42]. This is in line with theoretical perspectives arguing that frequent reliving and voluntary and involuntary retrieval could constitute attempts at integrating episodic memories into autobiographical knowledge, especially for traumatic memories, such as PMIEs [

79,

80]. The implication of these findings is that healthcare organizations should take action as soon as possible and provide nurses with psychological counseling and psychotherapy aimed at recontextualizing their memories of these events before they are fully integrated into autobiographical knowledge [

12].

We also found that episodic memories of PMIEs are need-thwarting, with memories of self-PMIEs being associated with significantly less autonomy and competence as compared to other-PMIEs, and with the latter being associated with more relatedness-thwarting than the former. Although we expected that autonomy would be more thwarted in memories of other-PMIEs, this was not confirmed by our results. A possible explanation would be that the environmental/external constraints perceived by nurses when perpetrating self-PMIEs were stronger than we had anticipated. This could also be the result of their attempting to reconciliate the information about the self from the memories of self-PMIEs with their morally good identities [

21,

25]. Intentionality is an important predictor of retaining episodic memories of moral transgressions, perpetrated by the self and by others, with more unintentional transgressions being judged less severely and, thus, more easily forgotten [

86]. In conclusion, since self-PMIEs are associated with more severe clinical manifestations and with more guilt [

5,

12], nurses may try to reconstruct their memories to better fit their conceptual selves by magnifying the autonomy-thwarting they felt during the events.

Regardless of the mechanisms at play in these instances, the need-thwarting in both types of memories could significantly impact their work identities as well. As such, they could perceive themselves as less competent and autonomous subsequent to self-PMIEs, which could redefine their professional roles as nurses, along with other parameters of psychological health and well-being [

25,

27]. Our findings indicate that at least burnout and turnover intentions are affected by this. Moreover, the relatedness-thwarting associated with memories of other-PMIEs may undermine their trust in the organization and in their superiors, which could lead to either helplessness or even disobedience when it comes to following physicians’ recommendations [

87]. Feeling disconnected from one’s peers would also affect patient care by impairing the necessarily good communication between the members of the medical team in charge of patient care [

7,

36].

Currently, there are few studies documenting the differential effects of exposure to self- and other-PMIEs [

5,

12,

13]. Distinguishing between self- and other-PMIEs is necessary to document their distinct pathological outcomes, better understanding reported symptoms, choosing clinical courses of treatment and estimating responses to treatment [

12]. Our study showed that higher burnout and turnover intentions associated with memories of self-PMIEs compared to memories of other-PMIEs are in line with past research on burnout [

5]. The same differences were found for EE, DP and AP. Moreover, our results indicate that the differential impact of self- and other-PMIE memories on the two work outcomes are mediated by basic psychological need-thwarting, a novel contribution to the literature, to the best of our knowledge.

Specifically, memories of self-PMIEs were associated with higher burnout due to more competence-thwarting, whereas memories of other-PMIEs were associated with higher burnout due to relatedness-thwarting, a pattern of differences we found only with EE. This is in line with previous research showing that EE in teachers was higher when they felt less competent or insufficiently connected with their students [

88]. It also supports past research showing how central moral values are for nurses’ professional identities, suggesting that feeling incompetent at their jobs can bring about feelings of strain and the depletion of emotional resources [

21,

89]. Moreover, it supports the importance of an inclusive climate in healthcare organizations, suggesting that feeling disconnected from one’s peers may have similar effects as feeling incompetent at one’s job. Interestingly, only relatedness-thwarting mediated the relationship between the type of memory and PA. This would imply that, upon witnessing other-PMIEs, the thwarted connectedness led to feelings of loss of professional efficacy, which would mean that nurses no longer expected to be able to perform their jobs according to their moral standards in a work environment allowing for such severe moral violations.

This interpretation is also corroborated by the fact that lower relatedness in memories of other-PMIEs was associated with higher turnover intentions, emphasizing that nurses might consider leaving a workplace or a profession where they cannot connect to their peers on moral grounds. Our participants were more likely to consider leaving their job due to autonomy-thwarting in the case of self-PMIEs. This is in line with previous research, which showed that perceived autonomy support at work decreases burnout, compassion fatigue and turnover intentions while also increasing work satisfaction, organizational identification, innovative behavior, work engagement and job performance [

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95].

Our findings also contribute to the growing body of knowledge supporting the hypothesis that episodic memories may remain accessible and functional even when/if they are not integrated into autobiographical knowledge (i.e., the memories-as-independent-representations perspective) [

25]. According to this perspective, and corroborated by our results, episodic memories may fulfill the function of encoding events relevant to one’s goal system but conflict with data previously deposited into the autobiographical knowledge and the conceptual self [

25]. Hence, memories of PMIEs may act as independent representations and guide actions and outcomes regardless of the conceptual self, which could be very dangerous for nurses as well as for other professional categories affected in this manner by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Concerning socio-demographic characteristics, our findings suggest that younger and more inexperienced nurses are more likely to be dissatisfied with their work in terms of their basic psychological need-satisfaction, as well as nurses who worked for more hours a week. This confirms previous findings showing that nurses’ basic need-satisfaction at work does not vary with level of education, marital status or sex, but that it does decrease with experience [

96,

97]. We also found that participants who were single, less experienced, younger or spending more time at work experienced more burnout. Previous research on the effects of age on nurses’ burnout has rendered mixed results, with findings suggesting that younger age significantly predicted higher emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, but not personal accomplishment [

51]. However, we found younger age to predict all three dimensions of burnout. A recent review of predictors of nurses’ turnover intentions showed that the COVID-19 pandemic may have increased nurses’ turnover intentions. The intentions were dependent upon nurses’ age and work experience, with younger and less experienced nurses being more likely to consider leaving the profession [

62]. Another predictor was the time spent caring for patients, with more time being associated with an increased turnover intention. Marital status and sex have traditionally predicted both turnover intentions and burnout [

59,

60,

61]. Our findings, however, suggest that only being single and weekly hours at work significantly impact nurses’ turnover intentions in our sample, in the sense that nurses who spend less time at work are less likely to consider leaving their jobs.

Our research is not without limitations. First, our design was quasi-experimental because we did not have a control group with which to compare our findings. Future research should verify our results by including a control group of nurses exposed to traumatic events without moral implications during the COVID-19 pandemic or nurses diagnosed with PTSD. Second, our research was cross-sectional, which means that we cannot draw any definitive conclusions regarding causality. Future studies should verify our findings longitudinally. Our sample of participants was not representative for the population from which it was drawn, although we strived to include nurses from several specialties. Finally, future research should also investigate the content of the memories of self- and other-PMIEs thematically. Although we had hoped that our participants would allow us to use their data this way, this was not the case, given the sensitive nature of the information. Hopefully, researchers in other geo-cultural contexts may accomplish this in future studies.

Our results indicate that unique events of exposure to PMIEs can have long-term consequences on nurses’ psycho-social functioning and well-being. Future research should contribute to the development of more effective training programs to adequately prepare nurses to deal with ethically challenging events. Early intervention programs for nurses showing mental health symptoms as a consequence of PMIEs should also be devised. Healthcare institutions should then provide them with access to the necessary psychotherapies to address these issues, according to the type of PMIE to which they have been exposed. For self-PMIEs, research has shown the efficiency of strategies to ease guilt and shame, such as contextualization, nonjudgmental acceptance of emotions, cultivating openness to receiving and providing forgiveness (to others and to self) and conciliatory actions [

98,

99]. For other-PMIEs, treatments focused on moral and/or spiritual repair could prove efficient [

100,

101,

102]. However, since the consequences of exposure to PMIEs are not reduced to intrapsychic conflicts, psychotherapy may not be enough for recovery. Healthcare organizations would have to make an affirmative community effort to comprehend and reintegrate workers exposed to PMIEs during the pandemic, and to accept shared responsibility for the occurrence of these traumatic events [

12].