Abstract

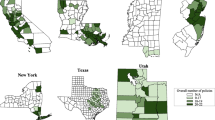

Epidemiologic research has found worsening behavioral health in the USA since 2020. Local policies may have contributed to these patterns and associated disparities. However, scant research has systematically documented county-level COVID-19-era policymaking or empirically investigated its health impacts. To investigate this question, we linked the US COVID-19 County Policy Database—a novel database with weekly data from 2020 to 2021 on 26 policies for 309 primarily urban counties—to data on adult behavioral health from the cross-sectional 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (N = 25,600). We created measures of policy comprehensiveness by aggregating individual policies into an overall score, and into three domains: containment/closure, economic response, and public health. Outcomes included any past-30-day use and frequency of use of multiple substances (alcohol, binge alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, non-marijuana illicit drug use, and vaping) and past-30-day psychological distress. Models adjusted for individual covariates, county fixed effects, and time-varying county-level COVID-19 covariates. We found that increases in overall policy comprehensiveness—and comprehensiveness in each of three domains—over time were not associated with the behavioral health outcomes assessed. Meanwhile, stratified models found some variability in associations across sex, racial/ethnic, education, and urban subgroups. This study established the feasibility, utility, and potential challenges of linking newly available COVID-19-related county policy data with health data to examine county-level policy influences on behavioral health. Further research is needed to inform responses to current behavioral health needs and future public health emergencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Data Availability

The UCCP Database used for this study is publicly and freely available to any investigator via the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR): https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR39109.v1. The NSDUH data used for this study are maintained as restricted-access data by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and are, thus, only available to investigators who request and receive approval from SAMHSA to access restricted-use data files, as described here: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/samhsa-rdc.

References

Wright E, Dore EC, Koenen KC, Mangurian C, Williams DR, Hamad R. Prevalence of and inequities in poor mental health across 3 US surveys, 2011 to 2022. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(1):e2454718. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.54718.

Kessler RC, Ruhm CJ, Puac-Polanco V, et al. Estimated prevalence of and factors associated with clinically significant anxiety and depression among US adults during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2217223. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.17223.

Villas-Boas SB, White JS, Kaplan S, Hsia RY. Trends in depression risk before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(5):e0285282. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285282.

Compton WM, Flannagan KSJ, Silveira ML, et al. Tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and other drug use in the US before and during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2254566. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.54566.

Chong WWY, Acar ZI, West ML, Wong F. A scoping review on the medical and recreational use of cannabis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022;7(5):591–602. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2021.0054.

Acuff SF, Strickland JC, Tucker JA, Murphy JG. Changes in alcohol use during COVID-19 and associations with contextual and individual difference variables: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Addict Behav. 2022;36(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000796.

Sohi I, Chrystoja BR, Rehm J, et al. Changes in alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic and previous pandemics: a systematic review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2022;46(4):498–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14792.

Schmidt RA, Genois R, Jin J, Vigo D, Rehm J, Rush B. The early impact of COVID-19 on the incidence, prevalence, and severity of alcohol use and other drugs: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;228:109065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109065.

Coughlin LN, Bonar EE, Bohnert KM, et al. Changes in urban and rural cigarette smoking and cannabis use from 2007 to 2017 in adults in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107699.

Maeng D, Li Y, Lawrence M, et al. Impact of mandatory COVID‐19 shelter‐in‐place order on controlled substance use among rural versus urban communities in the United States. J Rural Health. Published online June 16, 2022: https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12688. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12688

Brydon R, Haseeb SB, Park GR, et al. The effect of cash transfers on health in high-income countries: a scoping review. Soc Sci Med. 2024;362:117397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2024.117397.

Batra A, Jackson K, Hamad R. Effects of the 2021 expanded Child Tax Credit on adults’ mental health: a quasi-experimental study: study examines the effects of the expanded Child Tax Credit on mental health among low-income adults with children and racial and ethnic subgroups. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(1):74–82. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00733.

Cha E, Lee J, Tao S. Impact of the expanded Child Tax Credit and its expiration on adult psychological well-being. Soc Sci Med. 2023;332:116101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116101.

Wolf DA, Monnat SM, Wiemers EE, et al. State COVID-19 policies and drug overdose mortality among working-age adults in the United States, 2020. Am J Public Health. 2024;114(7):714–22. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2024.307621.

Assaf RD, Hamad R, Javanbakht M, et al. Associations of U.S. state-level COVID-19 policies intensity with cannabis sharing behaviors in 2020. Harm Reduct J. 2024;21(1):82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-024-00987-y.

Devaraj S, Patel PC. Change in psychological distress in response to changes in reduced mobility during the early 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: evidence of modest effects from the U.S. Soc Sci Med. 1982;2021(270):113615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113615.

Vo AT, Patton T, Peacock A, Larney S, Borquez A. Illicit substance use and the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States: a scoping review and characterization of research evidence in unprecedented times. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148883.

Ritchie J, Whiting M, Chaturapruek S, et al. Crowdsourcing county-level data on early COVID-19 policy interventions in the United States: technical report. Tech Rep. Published online 2021

Hurt B, Hoque OB, Mokrzycki F, et al. COVID-19 non-pharmaceutical interventions: data annotation for rapidly changing local policy information. Sci Data. 2023;10(1):126. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-01979-6.

Hamad R, Lyman KA, Lin F, et al. The U.S. COVID-19 County Policy Database: a novel resource to support pandemic-related research. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1882. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14132-6.

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): methodological summary and definitions. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2022. Accessed July 30, 2024. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-methodologicalsummary-and-definitions

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): methodological summary and definitions. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2021. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35330/2020NSDUHMethodSummDefs091721.pdf

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184.

Hamad R, Pletcher MJ, Carton T. United States COVID-19 County Policy Database, 2020-2021: version 1. Published online 2024. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR39109.V1

Matthay EC, Gottlieb LM, Rehkopf D, Tan ML, Vlahov D, Glymour MM. What to do when everything happens at once: analytic approaches to estimate the health effects of co-occurring social policies. Epidemiol Rev. 2021;43(1):33–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxab005.

Mummolo J, Peterson E. Improving the interpretation of fixed effects regression results. Polit Sci Res Methods. 2018;6(4):829–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2017.44.

Timoneda JC. Estimating group fixed effects in panel data with a binary dependent variable: how the LPM outperforms logistic regression in rare events data. Soc Sci Res. 2021;93:102486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2020.102486.

Greene W. The behaviour of the maximum likelihood estimator of limited dependent variable models in the presence of fixed effects. Econom J. 2004;7(1):98–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-423X.2004.00123.x.

Cintron DW, Gottlieb LM, Hagan E, et al. A quantitative assessment of the frequency and magnitude of heterogeneous treatment effects in studies of the health effects of social policies. SSM - Popul Health. 2023;22:101352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101352.

Veldhuis CB, Kreski NT, Usseglio J, Keyes KM. Are cisgender women and transgender and nonbinary people drinking more during the COVID-19 pandemic? It depends. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 2023;43(1):05. https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v43.1.05.

Kaashoek J, Testa C, Chen JT, et al. The evolving roles of US political partisanship and social vulnerability in the COVID-19 pandemic from February 2020–February 2021. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2(12):e0000557. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000557.

Allison PD. Missing data. In: Millsap RE, Maydeu-Olivares A, eds. The SAGE handbook of quantitative methods in psychology. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2009:72–89. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020994

Solon G, Haider SJ, Wooldridge JM. What are we weighting for? J Hum Resour. 2015;50(2):301–16.

Bakaloudi DR, Evripidou K, Siargkas A, Breda J, Chourdakis M. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on smoking and vaping: systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. 2023;218:160–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.02.007.

Koltai J, Raifman J, Bor J, McKee M, Stuckler D. COVID-19 vaccination and mental health: a difference-in-difference analysis of the understanding America study. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(5):679–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.11.006.

Van Draanen J, Peng J, Ye T, Williams EC, Hill HD, Rowhani-Rahbar A. No change in substance use disorders or overdose after implementation of state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2024;260:111344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2024.111344.

Galasso V, Pons V, Profeta P, Becher M, Brouard S, Foucault M. Gender differences in COVID-19 attitudes and behavior: panel evidence from eight countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(44):27285–91. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2012520117.

Morgan E, Dyar C. Rural and urban differences in marijuana use following passages of medical marijuana laws. Public Health. 2024;234:64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2024.05.036.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Matthew Brandner, Kristin Lyman, Alexis Shuck, Bonnie Situ, Carol Garcia, Claire Purcell, Devon Linn, Jaime Orozco, Jordan Vogel, Leslie Cataño, Michele Humbles, and Soo Park for contributions to the collection of the UCCP Database; Amy Chiang for contributions to UCCP Database cleaning and code review; and the policy subgroup members of the COVID-19 Citizen Science project for their early input on policy data collection. Funding for this work was provided by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (grant number COVID- 2020 C2 - 10761) and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number U01MH129968). The funders had no role in the design of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The collection of the UCCP Database was determined to be Not Human Subjects Research by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (IRB24 - 1015). Our analysis of secondary, non-identifiable NSDUH data was also deemed not human subject research for which no IRB application was required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wright, E., Dore, E.C., Jackson, K.E. et al. County-Level COVID-19 Policy Comprehensiveness and Adult Behavioral Health during 2021. J Urban Health (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-025-00982-z

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-025-00982-z

Keywords

Profiles

- Rita Hamad View author profile