Abstract

Industrial Parks (IPs) in Africa, especially Ethiopia’s Hawassa Industrial Park (HIP), are seen as vital for boosting exports, creating jobs, and enhancing skills. However, the global pandemic’s disruptions to production and employment prompt a reevaluation of this view. Drawing upon extensive ethnographic research conducted at Ethiopia’s flagship state-owned IP, the HIP, we delve into the multidimensional crises faced by the country’s industry during the pandemic. We identify various methods employed by the Ethiopian government to persuade workers into accepting disproportionately low wages, with the aim of retaining foreign investors and stabilizing the national economy. Our analysis reveals the reinforcement of precarious livelihoods among HIP workers, characterized by heightened vulnerability and job insecurity due to the pandemic-induced disruptions. Contrary to the state’s depiction of HIP as an emblem of industrial progress, workers at HIP champion narratives and strategies to assert their rights and improve working conditions. This research underscores the importance of reimagining Africa’s industrialization strategy, emphasizing the well-being of its labor force in a post-pandemic world.

Article Highlights

-

The study findings showed that IP workers experienced increased vulnerability and job insecurity due to disruptions caused by the pandemic.

-

In the study, we strongly argue that contrary to the state’s depiction of the IPs as an emblem of its developmentalist orientation, workers at HIP struggle for their rights and improved working conditions.

-

The finding underscores the rise of vulnerable livelihoods, a changing landscape of challenges, and the quest for new perspectives on Africa’s future progress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Hawassa, situated on the scenic shores of Lake Hawassa, has been renowned for its diverse tourist attractions. As the administrative center of the newly established Sidama regional state, Hawassa has a population nearing 5 million within a 50-km radius, marking it as one of Ethiopia's most densely populated urban regions. Its strategic importance is amplified by its location on the Trans-African Highway, connecting Cairo to Cape Town and providing a direct route from Addis Ababa to Moyale in Kenya. This positions Hawassa as a potential linchpin in regional trade within the East African Community. The upcoming US$667 million expressway will further enhance its connectivity, linking it to Modjo in central Ethiopia.

On July 13, 2016 -Ethiopia’s then Prime Minister, Haile Mariam Desalegn, launched the HIP, a nation-level textile and garment IP overseen by the Industrial Park Development Corporation (IPDC). Constructed by a Chinese firm with a budget of $250 million, HIP has garnered significant foreign direct investment (FDI) from global apparel manufacturers from the United States, Siri Lanka, India, among other countries. The inauguration witnessed participation from dignitaries, diplomats, investors, and locals. The Prime Minister hailed HIP as a ‘‘foundation in Ethiopia’s ambition to be the manufacturing hub of the African continent’’ [1]. He envisioned the park elevating Ethiopia within the global textile and apparel industry, thereby catalyzing job creation and economic growth in the country.

The case of HIP illustrates how IPs serve as a vital component of Ethiopia’s comprehensive plan to sustain unprecedented economic growth and attain middle income country by the year 2025, in conjunction with extensive investments in roads, railway lines, hydroelectric dams, and other critical infrastructure. These concerted efforts signify Ethiopia state’s commitment to transforming its economic landscape and reinforcing its position as a rapidly emerging industrialized nation. However, the COVID-19 pandemic poses a challenge for Ethiopia’s ambitious industrialization agenda focused on export-oriented light manufacturing.

This paper contributes to this critical investigation of IP’s promise and performance through the experiences of workers from 2020 to 2023. We focus on the impacts of global pandemics on Ethiopian economies, labor market, as well as individual workers’ lives and livelihood strategies. Drawing upon ethnographic research conducted in HIP during the time period, we explore ways that the Ethiopian government continues to convince workers to sell their labor at a very low price in order to retain foreign investors and stabilize national economy. We trace the shifts in employment patterns and the corporeal experiences of workers in HIP, who are mostly migrants from rural area, lived in periphery area of the city and explore adaptive strategies. By so doing, we seek to problematize state vision and representation of HIP as industrial promises and uncover the uncertain future experienced and shared by workers during and after the pandemic.

Drawing from diverse strands of literature on IP-led industrialization, neoliberal labor regimes, and global value chains (GVCs), this paper seeks to answer the following questions: How has COVID-19 impacted IPs in terms of production, supply chains, and employment? How have the pandemic’s effects cascaded down to workers’ conditions and well-being? How did various stakeholders react to the pandemic’s challenges, and what implications did these responses hold for workers? Answering these questions will allow us to make three modest contributions to the literature. First, it enriches the literature by shedding light on the intricate interactions between workers and IPs, highlighting the emergence of precarious livelihoods, an evolving realm of struggle, and the search for alternative narratives about Africa’s future development. Second, the paper implicitly underscores that an employment and labor-centric analysis offers deeper insights into industrial transformation and human well-being in Africa. Lastly, this study aids policymakers and stakeholders in comprehending employees’ pandemic experiences, their often-invisible lives, and unheard voices.

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 conceptualizes the IP-based development and its employment outcomes in the literature and in the empirical context of Ethiopia. Section 3 focused on employment and labor in times of multiple crises faced by Ethiopia and Ethiopians. Section 4 documents the case study on HIP and the research methods. Section 5 substantively evaluates employment precarity inside the HIP and workers’ lives during the 2020–2023 periods. Section 6 explores government responses during the pandemics. The last section concludes the paper.

2 GVCs, labor regimes and IP-based industrialization

GVCs have become increasingly prominent as economic convergence and inter-regional connectivity intensify in a globalizing world. The reach of globalization has made production feasible wherever inputs are accessible through offshore outsourcing [2]. Many believe that engagement in these global networks will enhance national industrial development. Although the apparel export industry has historically been approachable for entry, shifts in the global economy have raised barriers for local enterprises in low-income nations [3]. Ethiopia, grappling with low productivity and high logistical costs, strives to compete within GVCs by maintaining low wages, which has been primarily achieved through a proactive, state-driven industrial policy over the past decades [4].

Long-standing discussions center on the ways in which low-income nations can effectively engage with the global economy through GVCs, aiming for sustained economic transformation rather than ‘thin industrialization’ or ‘immiserizing growth’ [5, 6]. While entering foreign markets offers firms the potential for growth and provides workers with enhanced job prospects, the imbalanced power dynamics between lead firms and their local suppliers can limit this potential [7, 8]. Many supplier firms in developing countries face diminishing profit margins as lead firms benefit from reduced production expenses [9, 10]. The outcomes for workers are intricately tied to their role in these global production networks, as their agency can shape social relations of production both within and beyond the workplace [11].

Despite existing insightful studies, the dimension of employment relations within GVCs remains relatively under examined [12]. The predominant focus has been on influential ‘lead firms’ that preside over value chains [13]. Neil Coe & David Jordhus-Lier [14] argue that a significant portion of GVC literature tends to regard labor as inherently integral to the production process, often characterizing workers as passive subjects in the face of capital’s relentless pursuit of cost efficiency. In light of this, they advocate for a more nuanced attention to labor agency in GVC studies. In a parallel vein, Christina Niforou emphasizes that the notion of ‘‘private governance,’’ especially actions spearheaded by lead firms, has somewhat overshadowed the significance of community and worker-initiated endeavors [Niforou, 2015, as referenced in 12].

To understand the significant shifts impacting the working conditions of migrants in IPs, especially in the context of temporary or prolonged unemployment, employment transitions, changing work environments, and income volatility, it is essential to employ a range of theoretical frameworks. One notable approach is the labor regimes concept, which provides a valuable analytical lens to examine how internal and external factors within and beyond the factory influence disparities across workplaces [15]. Regarding to this, Brass [16] argues that capitalism is compatible with unfree labor, which emerges when it serves the economic or political interests of capital. He contends that labor unfreedom is a product of the struggle between capital and labor, drawing parallels with political freedom and regime change [17].

Built upon labor process theory, labor regimes delineate the complex interrelations among labor market segmentation, workforce mobilization, employment terms, and mechanisms of enterprise authority that influence the appropriation of surplus value [18]. Embracing the labor regimes approach illuminates the multifaceted political-economic and socio-cultural dynamics, processes, and contexts that shape and sustain dispersed labor networks, spanning from local to international spheres [19]. Furthermore, the labor regime contributes a valuable intermediary concept bridging the day-to-day labor processes in a specific workplace and the broader ‘‘general forms of domination’’ inherent to capitalism [20]. This approach offers a substantial analytical grip on how labor control mechanisms, disseminated vertically through inter-firm interactions within global production networks, intersect with territorial or ‘horizontal’ labor regulation systems to ultimately shape labor conditions [21].

This theory suggests that the organization of work is not just a technical matter but is deeply influenced by social, political, and economic dynamics. There have been multiple shifts in labor regimes over the past decade. Contemporary analyses strive to integrate global perspectives while refocusing on the nuances of social differentiation. The rise of economic globalization in the 1990s and 2000s, coupled with the emergence of segmented GVCs and production networks, highlighted the imperative to understand these structures’ direct effects on labor [22].

The labor regime theory has been used to explore diverse topics, ranging from the rise of the service sector and the spread of informal labor to the changing nature of work in the global context [21]. It also proves insightful for grasping the dynamic interactions between the state, capital, and labor, especially in pandemic situations. In the context of increasing globalization and the advent of neoliberal labor practices, it is crucial to understand Ethiopia’s IP-based industrial policies, characterized by low wages and minimal labor protections. While many studies have examined overarching themes such as policy responses [23], policy execution [24], and the efficacy of the state [25], relatively few have delved into employment precarity in Ethiopia context.

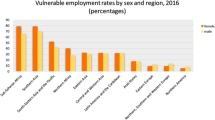

In Ethiopia, the development of IPs represents a strategic initiative to fulfill an ambitious industrialization vision encompassing both manufacturing and agro-processing sectors. With an objective to accelerate economic transformation, the Ethiopian government is keen on attracting labor-intensive FDI to boost export-oriented manufacturing [26]. Despite such government plan, manufacturing sector’s contribution to total export earnings have only grown from 0.5 percent in 2010s to merely 5 percent in 2022. To address this challenge, IPs have emerged as a central strategy to attract foreign investors with appealing incentives and logical supports and provide jobs for the nation’s sizable youth populace. IPs are touted as pivotal to economic development and structural transformation, driving growth, diversification, upgrading, and competitiveness [27,28,29]. Consequently, numerous IPs have sprouted across the nation in recent years. As of 2023, the IPDC reports that 13 government-owned IPs are operational, generating employment opportunities. These IPs employ hundreds of thousands of workers, predominantly composed of young, less educated, and rural migrant women. Nevertheless, with such low payment, and documented practices of union busting, HIP’s predominantly young, feminised and migrant labor force has become an ideal example of labor exploitation by global capital.

3 Crises and disruptions

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on workers and labor markets globally, especially in developing countries. In the just-in-time economy, these workers often live and work in close quarters, making them particularly vulnerable to disease transmission [30]. The pandemic’s effects on workers’ rights and unions have varied across countries, generally reinforcing existing state-labor relations patterns rather than transforming them [31]. For example, in India and Singapore, the crisis has brought to the forefront deeply ingrained socioeconomic inequalities and exclusionary practices towards migrant workers, challenging these nations’ narratives of economic success [32]. In China’s Southeast Asian IPs, night time light data has revealed that most parks maintained better operating conditions in 2020 compared to 2019, despite the pandemic’s negative effects [33]. The pandemic has exposed the precarious conditions of migrant workers in various sectors, including production, care, and transport [30]. In Vietnam, migrant workers in IPs and export processing zones faced challenges due to social distancing measures and reduced working hours, leading to income loss and financial difficulties [34]. These studies highlight the complex impacts of COVID-19 on Asian IPs and their workers, underscoring the need for effective social security policies and recovery strategies.

Amidst Ethiopia’s endeavor to reshape its economic landscape, a complex interweaving of local challenges and global dynamics is unfolding. The confluence of events – COVID-19’s impact, Ethiopia’s African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) exit due to internal conflicts, the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and persistent high inflation – has pushed migrant laborers into precarious work and living situations. As a result, they have become one of the most marginalized and vulnerable groups within Ethiopia’s formal labor market.

3.1 Compound crises

Since its outbreak in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, COVID-19 has presented unparalleled global challenges, impacting individuals across income, race, and religion. Following its official declaration in March 2020, multiple sectors, including finance, supply, demand, and health, experienced significant disruptions. In response, governments worldwide implemented measures ranging from partial business closures to mobility restrictions, leading to profound socio-economic repercussions [35].

The world’s economic recovery now faces potential roadblocks due to emerging COVID-19 variants [36]. Businesses, especially in IPs, confront supply chain interruptions, reduced demand, and essential resource shortages [37, 38]. Particularly hard-hit are emerging economies like Vietnam and Ethiopia [39, 40]. Within IPs, companies grapple with limited foreign inputs and decreased labor availability, hampering industrial production [41]. The African labor market has been notably strained, with an estimated loss of 25 to 30 million jobs in 2020 [42].

Ethiopia identified its first COVID-19 case in Addis Ababa on March 13, 2020 [43]. In a nation already grappling with precarious living conditions, the pandemic’s onset led to over 467 thousand infections and more than 7.4 thousand fatalities by mid-February 2022 [44]. Beyond straining healthcare capacities, the pandemic has incited multidimensional socio-economic and political reverberations, resulting in rising unemployment, institutional closures, supply chain interruptions, and increased food insecurity [23, 45].

The manufacturing sector, especially the global readymade garment industry, has been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. As Demeke et al. [46] highlight, the industry has faced a steep decline due to significant order cancellations. This downturn has especially jeopardized the livelihoods of low-wage, often inexperienced and unskilled production workers, positioning them as cost-effective labor options. For many migrant workers, accessing basic necessities is an ongoing challenge. The devaluation of the Ethiopian Birr, a move that is also advocated by the IMF and World Bank, compounded by increased prices for commodities and energy due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, has intensified food insecurity for the urban poor. These workers face the double bind of escalating living costs without a commensurate rise in wages. Their inability to secure KebeleFootnote 1 identity cards further restricts them from accessing government-subsidized cooperative union shops, complicating their daily survival.

In this complex landscape of challenges, the notion of IP-driven economic transformation in Ethiopia requires urgent reassessment. Notable studies, such as those by Demeke et al. [46] and Mengistu et al. [41], have spotlighted the shocks IPs have endured on both the demand and supply fronts. Regrettably, the government’s overarching economic objectives seem to overshadow the well-being of young women working within IPs. In their quest to draw foreign investment, IP workers remain beleaguered by regional and global shocks. Despite the optimistic promises, a sobering reality of struggle and uncertainty prevails. The female migrant workforce, in particular, endures the most of these hardships.

3.2 Implications of Ethiopia’s suspension from the AGOA

The U.S. decision to suspend Ethiopia’s AGOA participation, citing ‘gross violations of human rights,’ in the context of Ethiopia’s civil war caught stakeholders off guard.Footnote 2 The AGOA was passed in 2000 and came into effect in 2001. Initially signed by Bill Clinton, it was extended by George W. Bush in 2004, and has enjoyed bipartisan support in Congress. The act has been significant in providing preferential trade with African countries, particularly in the form of duty-free and quota-free access to U.S. markets for various products, with a notable emphasis on garments and textiles.

The U.S. announced it would suspend Ethiopia from AGOA in November 2021, at a time when the manufacturing sector was still reeling from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ethiopia had been the fifth top exporting nation under the act.Footnote 3 Ethiopia’s chief trade negotiator Mamo Mihretu told Reuters New Agency that AGOA had directly created 200,000 jobs.Footnote 4 In 2020 Ethiopian exports under AGOA totaled $238 million, primarily from the garment industry [29]. The lack of orders due to Ethiopia’s ban from AGOA led to a slowdown in production and employment. The factory occupancy rate also decreased. Ethiopia’s suspension from AGOA threatened job stability across the global value chain, with the garment sector’s impoverished women bearing a disproportionate burden. By 2019, the U.S. was the destination for 70 percent of Ethiopia’s textile and garment exports, a sharp rise from 15 percent just five years earlier. Ethiopia’s suspension from AGOA placed nearly 56,000 IP-based jobs in jeopardy [47].

These circumstances create considerable uncertainty for the future of the parks and the development gains achieved to date. Many workers in the HIP, grappling with job insecurity, inflation, and societal challenges, expressed feelings of estrangement, disillusionment, and despair. Depending on the product type and materials used, the duty advantages under AGOA allowed buyers importing into the U.S. to save close to a third of the total value of finished goods at the point of U.S. entry. Given that imported fabric can represent up to two-thirds of the value of finished products these duty savings could be equivalent to all local costs or Ethiopian economic value-added.

3.3 Impacts on IPs and employment

In Ethiopia, the COVID-19 crisis has exerted a far-reaching impact on health, livelihoods, economic growth [48], social relations [23], and overall well-being [45]. Despite Ethiopia’s relatively effective measures in controlling the virus’s spread, the pandemic’s economic consequences are poised to be severe. As per the World Bank’s analysis, Ethiopia’s vibrant economy, previously growing at an annual average of 9.4 percent since 2010, diminished from 8.4 percent in 2019 to 6.1 percent in 2020, with a further contraction to 2.4 percent in 2021. The economy’s growth rate has moderately recovered to 4.3 percent in 2022, 7.9 percent in the 2023/2024 Ethiopian fiscal year, yet it continues to be hampered predominantly by the COVID-19 pandemic’s impacts [49].

During the state of emergency, despite regulations against employee layoffs, estimates from the Jobs Creation Commission indicate a potential loss of nearly 1.5 million jobs across manufacturing, construction, and services within the pandemic's first three months [50]. Physical distancing measures could have further exacerbated this loss, especially in manufacturing and construction, with potential job cuts nearing 1.1 million [51].

A growing body of literature is shedding light on the pandemic’s ramifications, revealing not only its impact on vulnerable individuals and groups but also the crisis it has induced across Ethiopia’s health, economic, and social systems. For instance, Demiessie [52] delves into the pandemic’s uncertainty shock and its short-term impact on Ethiopia’s macroeconomic stability. The study underscores how the Ethiopian economy’s reliance on imports for consumption and investment goods made it susceptible to the pandemic’s uncertainty effect, which began as a supply chain shock and transmitted its repercussions through international trade channels.

COVID-19 significantly affected larger industries during the lockdown, primarily due to their dependence on hired labor. Conversely, smaller businesses, particularly micro-enterprises operated by family labor, experienced less disruption due to the lockdown [45]. Additionally, the pandemic together with the repercussions of AGOA termination led to a decline in FDI. The establishment of the IPDC brought a positive influx of investors, averaging 32 per year (See Table 1.). However, the outbreak of COVID-19 adversely impacted this investor inflow. A comparison between the years 2019/20 and 2020/21 reveals a notably diminished annual growth rate of 0.02, the lowest in previous years.

The pandemic also precipitated a financial decline in companies’ revenues. Reports indicate that the annual export volume was on a significant upward trajectory prior to the outbreak of COVID-19. However, with the advent of the pandemic, annual exports experienced a dramatic downturn. This observation aligns with Mengistu et al. [41], who emphasize the substantial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on production within Ethiopia’s IPs, affecting both the extensive and intensive margins. Broadly assessing Ethiopian firms, Krishnan et al. [54] found that around 10 percent of surveyed firms reported temporary closures due to COVID-19. Furthermore, over three-quarters of firms noted declines in sales and production volumes, averaging a 42 percent decrease in sales and a 40 percent drop in production.

One of the primary goals of IPs is to provide diverse employment opportunities. Since 2014, the number of workers in IPDC-owned IPs has steadily increased, contributing around 30,095.5 new positions per year over the past six years. Nevertheless, as shown in the Table 2, the growth trajectory has been significantly impacted by the advent of COVID-19.

4 Case study on HIP

The case study focuses on the HIP, a government-owned flagship IP situated near Lake Hawassa, approximately 275 km from Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa. Constructed by China Civil Engineering Corporation, the project commenced in July 2015 and was inaugurated on July 13, 2016. HIP has emerged as an enticing hub for labor-intensive industries, aligning with Ethiopia’s broader goal of economic transformation [55]. HIP, at a cost exceeding $250 million, stands as Africa’s largest textile and apparel IP. Encompassing a total area of 2.3 square kilometers with a construction space of 230,000 square meters, the park features 38 factory sheds, ancillary facilities, and presently employs 22,000 individuals (as of August 2024).

In line with its objectives, the establishment of HIP has unlocked employment opportunities across various skill levels for individuals residing in and around Hawassa city. Approximately 90 percent of factory sheds are occupied by 23 organizations and anchor investors hailing from the U.S., Europe and Asia [53]. Notably, on March 4, 2017, one of HIP’s tenants exported the park’s inaugural dress shirt. Over the last three decades, Ethiopia’s manufacturing sector generated a mere 250,000 jobs [1]. While the government envisioned HIP to generate up to 60,000 jobs and $1 billion in export revenue upon completion, a lack of comprehensive analysis and projection has hindered the realization of these ambitions.

Despite attracting significant scholarly and media attention, there remains a dearth of qualitative, comprehensive labor-focused studies detailing the pandemic’s impact on capital-labor relations and employment dynamics within Ethiopia’s IPs. This void persists even though the Ethiopian government has invested substantially in enabling infrastructure and established a network of IPs to stimulate FDI in sectors conducive to export growth and global integration.

4.1 Study design

The study is primarily qualitative, and within qualitative research design, we employed a combination of three interrelated approaches. The first approach is ethnography (fieldwork), in which we describes and interprets the life and characters of workers’ corporeal in detail. One of the main benefits of this study design is that it permits the researcher to observe events, listen to conversations, physically interact with objects, take part in activities, and ask questions about the details of what, where, why, and when things occur [56]. Second, in the course of this study, the researchers conducted individual and group in depth interviews with HIP workers, HRM heads, government representatives, former HIP workers, house owners, NGO representatives and expertise. Third, secondary data gathered from various credible books, journal article, online and other sources of information.

Meanwhile, in order to answer the question ‘how and why’, this study used a content/theme data analysis technique. Consequently, adapting interpretive epistemology and relativist ontology, we explore about migrant laborers multiple life experiences in the shadow of infrastructural promises.

This research rests on multiple fieldwork phases conducted in Hawassa between November 2019 and July 2023. The fieldwork aimed to gather the life stories of workers (12), perspectives from landlords (8), elders, and local authorities (14) who influenced workers’ living and working conditions. Interviews and factory visits included current and former workers, spanning pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods (65). While our sample size and selective interviews limit generalizability, the participants shared similar views on their experiences during the pandemic. Worker interviews primarily delved into their pandemic experiences, coping strategies, and motivations to remain in or depart from Hawassa. Additionally, semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders within the park’s management and government officials (7). Triangulating this information with secondary sources, academic experts, development specialists, and NGOs (9) provided a comprehensive perspective. Furthermore, this paper draws insights from existing literature, news articles, public documents, and promotional materials to highlight the pandemic’s severity, modes of transmission, and mitigation strategies.

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Lived experiences and workers’ strategies

The elitist vision presented to workers is a transformative journey from rural landscapes to urban factories, offering consistent earnings and an elevated standard of living. Enticed by the allure of integrating into the global supply chain and transitioning from agricultural life, numerous Ethiopians have pursued this path. Yet, the reality they encounter often starkly contrasts with these aspirations. Modest salaries, demanding work environments, and rising inflation quickly dampen their initial optimism.

In the context of HIP, women transitioning from rural locales to Hawassa in pursuit of jobs within the park anticipate consistent employment and the ability to uplift their families’ fortunes. Yet, realities often misalign with the aspirations of the young Ethiopians employed in these factories, leading to increasing absenteeism [57], elevated attrition rates [58], and instances of worker resistance [15], all impacting the sector’s overall efficiency [59, 60]. Our investigations reveal that such disruptions not only induce changes in job roles, work conditions, and compensation, but also necessitate adaptations to diverse labor types. Furthermore, these challenges often plunge workers into conditions of impoverishment, exploitation, and societal upheaval. Yet, it’s pivotal to note that these workers are not mere passive subjects; they employ varied approaches and adaptive strategies to persevere and uncover potential opportunities.

5.1.1 Employment precarity

The Ethiopian Investment Commission has actively attracted potential investors by promoting ‘‘Rikash gulbet’’, an Amharic term that translates to affordable labor. This positions Ethiopia as a prime business destination for global corporations seeking a vast reservoir of cost-effective labor. While HIP offers tempting benefits such as initial income tax breaks and exemptions on importing key goods, it is the labor affordability that differentiates Ethiopia as a preferred locale for international firms.

Many assembly line workers within the park earn less than a dollar daily, approximately one-fourth of Bangladesh’s minimum wage. An operator’s wage tends to be around $50 monthly, fluctuating between an entry-level $32 and $122 for highly skilled operators [61]. A study by Barrett & Baumann-Pauly [59] attests to the exceptionally low wages in the textile and garment sector, highlighting the absence of a mandated minimum wage for the Ethiopian private sector. Other studies indicate that entry-level workers at HIP typically earn an average of $26 monthly, merely 40 percent of the country's average per capita income and inadequate for covering basic needs [58].

Youth unemployment looms large in Ethiopia, underscoring the urgency of creating enhanced job opportunities. Intriguingly, the government has even spearheaded recruitment initiatives. Officials journey across villages, sharing tales of prosperity to potential workers. While the government and international corporations pursue economic objectives, young women from rural areas migrate to the park, motivated by dreams of stable employment and supporting their families. From our interviews, a recurrent theme became evident: women hailing from rural locales and small towns usually conclude their education by grade 8 or 10. Factors like landlessness, limited income, and lack of higher education often inhibit their access to formal jobs. Yet, their aspirations are reignited when they come across enticing recruitment advertisements, as former worker at HIP nostalgically recollects her arrival in Hawassa:

We were unable to purchase basic materials due to a lack of money such as: blankets, sheets, and food. Because of the promises we received from officials, we expected a lot in Hawassa when we left our houses: more than 3000 Ethiopian Birr (EB) salary, housing and the work environment would be quite comfortable (Interview, January 2021).

After HIP’s launch, the sight of young women, arriving in Hawassa by bus from diverse regions and clutching modest belongings, became emblematic of their hope. Another employee remembers:

Today, rural life is difficult, particularly for women who stay at home and do nothing. Then, I traveled to Hawassa with full of anticipation and curiosity, but the truth is much different (Interview, May 2023).

Workers’ stories often mirror each other. They recount unmet expectations, characterized by a jarring difference between initial promises and actual experiences at HIP. Such mismatches between aspirations and actualities contribute to a high attrition rate, as many leave upon disillusionment.

To entice companies and bolster the economy, the Ethiopian government has consistently strategized to maintain worker wages attractively low for businesses. Housing, a contentious issue, stands as a recurrent grievance. Despite its construction by the government, dormitories are supervised by private entities, where four women typically share a tight 4X4 space, paying about 40 percent of their income as rent. These cramped quarters lack basic amenities, leading one resident to describe it as ‘‘more like a prison house’’ (Interview, August 2020).

Due to the high cost of housing rentals in Hawassa, coupled with inflation, safety concerns, and anxiety, many workers contemplate relocating from the city center to Chefe, situated on the outskirts of Hawassa. However, this shift exposes them to various challenges, including physical assaults, theft, and even sexual assault. In an interview with the Ethiopia News Agency, Lelise Neme, former CEO of IPDC and then Ethiopian Investment Commission commissioner, highlighted the critical issue of housing shortage surrounding the park. This predicament has forced numerous workers to abandon the parks (2019).Footnote 5

The prevalence of cheap labor is orchestrated by Ethiopia’s developmental ambitions. Barrett & Baumann-Pauly position Ethiopia at the bottom of the list of countries in the textile and garment sector with an average wage of $26 a month [59]. Their insights into factories within Ethiopia’s primary IPs highlights how international brands benefit from the plight of workers who, while seeking employment, struggle to subsist on these meager wages. It is crucial to underscore that urging workers to accept such limited compensation can cascade into broader issues like poverty, exploitation, and potential societal disturbances. Therefore, it is incumbent upon the Ethiopian government to enact policies that ensure decent wages, fortify labor laws, and provide a safety net for its workers.

5.1.2 Workers’ life during the crises

For the rest of the section, we dissect the impact of the compound crises on workers’ lives through three specific lenses (Fig. 1). The first lens examines the direct, immediate effects of these crises on employment trends and conditions within the HIP. Our findings revealed workers confronting various challenges in the park, notably, insufficient safety protocols concerning distancing, sanitation, and mask-wearing. The second lens shifts to the ramifications on workers’ socio-economic existence beyond the park’s confines, especially their life as migrants in urban settings. This revealed feelings of isolation and heightened anxiety due to changing relationships with landlords and neighbours, compounded by food scarcity. Finally, the third lens zooms out to consider the implications for workers’ families, primarily based in rural locales. Here, workers contend with supplementary challenges that affect their families, including transportation barriers and safety worries. Together, these three lenses offer a comprehensive view of the tribulations and responses of IP workers in the face of the pandemic.

5.2 Inside the park

In line with the ramifications of COVID-19 on industries and supply chains, Ethiopia’s IPs, especially its textile and apparel sectors, have faced significant disruptions. This is evident in the HIP, where the pandemic’s impact has led to what’s described as a ‘‘combined demand and supply shock’’ [41]. As a result, almost half of the active factories within HIP halted operations post-outbreak, offering employees a three-week paid leave. With the park predominantly exporting to the US and Europe, the decline in orders further underscored the pandemic’s substantial influence. JP Garment, a Chinese textile firm which initiated operations in early 2020, encountered significant setbacks. An official from the company remarked:

We were just starting and awaiting various materials from abroad. Orders were expected from U.S. and European buyers. Moreover, we had already hired more than 300 new workers. However, the pandemic disrupted our plans, resulting in income, time, and resource losses (Interview, April 2023).

The crisis left many companies deliberating the retention of their workforce. A senior HR professional mentioned, ‘‘losing our skilled staff was a major setback for us.’’ Another production manager added, ‘‘Apart from labor absenteeism, the inability to afford and access inputs from abroad has hindered meeting our production targets.’’ As a result, the pandemic has profoundly altered the employment landscape in the HIP. In response to the challenges, businesses implemented changes such as cutting working hours and reducing wages. A migrant worker from a rural area mentioned, ‘‘I was not achieving my target bonus, hence I earned only 1,300 EB (23.85 $) per month and spent many hours at home without work. For many, these adjustments introduced severe financial strains''.

Due to heightened levels of uncertainty and volatility to the business landscape, making long-term planning for companies challenging and shaking job security for workers. An article from Addis Fortune newspaperFootnote 6 highlighted that the pandemic intensified pre-existing disparities in the labor market. It especially affected women, those with lower skills, and recent migrants from rural areas with minimal work experience. The economic downturn led to reduced demand for products and services, prompting layoffs across sectors.

Multiple media outlets reported that, in 2020, the park temporarily let go of over 14,000 out of its 34,000 employees, with some receiving paid or unpaid leave.Footnote 7 This decision stemmed from the decline in business, especially from American and European markets. Some of these workers were later rehired. Research from late May highlighted that, of 3,163 female workers in the HIP surveyed, 56 percent remained employed, 24 percent were on paid leave, 11 percent left voluntarily, 2 percent were terminated, and a small fraction were on unpaid leave [24, 29]. Further, a study by Harris et al. [48] underscored notable shifts in employment within the HIP. By mid-2020, 41 percent of those who had been employed in the HIP at the start of the year had either been placed on leave or lost their jobs. Alarmingly, of those who became unemployed, very few found alternate employment, and many relocated away from Hawassa. These changes, including reduced work hours, wage cuts, and job losses, gravely affected workers dependent on their monthly salaries.

The pandemic has also impacted workers through potential exposure to the COVID-19 virus within the workplace. While there are mixed opinions about the effectiveness of physical distancing and temperature checks implemented by the park, the administration claims to have provided necessary health safety equipment like masks, sanitizers, and soap. However, there have been complaints about the perceived lack of support from HIP administrators and industry leaders. A senior HR expert noted, ‘‘most factories made earnest efforts to safeguard their workers. For instance, several factories conduct daily temperature checks at the entrance and provide gloves, masks, and sanitizers. However, due to the high number of workers, shortages often occur ’’.

The IPDC, along with the park’s management, has implemented measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19. These measures include restricting visitors, setting up task forces and command centers, and placing thermal cameras within IPs to monitor body temperatures [62]. These initiatives align with the guidelines of the Ethiopian Public Health Institute, which oversees testing and contact tracing. Factories reportedly prioritize virus awareness and prevention, enforce social distancing both at work and outside, sanitize public spaces, supply sanitary facilities and personal protective equipment, and conduct temperature checks at entry points [24, 62].

However, the nature of assembly-line work exposes workers to risks, as many touch the same products. Most participants agreed that their roles were risky, particularly due to shared item handling and insufficient protective gear. A 23-year-old female worker from an Indian company voiced her concerns, ‘‘Working under these conditions is highly perilous. My safety from COVID-19 is never assured while working here.’’ She admitted that, despite personal use of sanitizer after each task, uncertainty persists due to inconsistent precautions taken by others.

In light of recent conversations with a senior HIP official, it appears that the pandemic, while presenting challenges, also uncovered unforeseen opportunities. Some businesses have expanded their production to include certified reusable face masks, catering to the increasing demand both locally and internationally. The official revealed that in response to the pandemic-driven demands, factories within the HIP shifted to mask production (Interview, March 2023). As Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed shared on Twitter, ‘‘Companies are currently producing 10,000 face masks per day with a plan to increase to 50,000 per day. Our industries are adapting to the times. Companies in HIP undeterred and shifting operations to meet immediate needs.’’Footnote 8 Furthermore, HIP reported earnings of $114 million from face mask exports during the fiscal year.

Despite limited NGO and local authority involvement, many participants noted the support of local social organizations. An interviewee shared, ‘‘during a month of unemployment, I received a basic income. It wasn't enough to sustain me in Hawassa, but some neighbors assisted by providing essentials like bread and vegetables.’’ A landlord further emphasized community support, saying, ‘‘we help one another as best we can. Personally, I have aided three workers by providing items like collard greens, oil, and salt ’’.

5.3 Around the house

The advent of COVID-19 has brought forth a plethora of challenges for employees within the IP. Many workers have encountered pay reductions or layoffs due to order cancellations and safety protocols. While everyone is grappling with unprecedented difficulties, the brunt of COVID-19’s economic and social repercussions is being borne by manufacturing employees, particularly women and rural migrants. The declaration of a state of emergency in Ethiopia on April 8, 2020 amplified challenges for those already disadvantaged pre-pandemic, such as women, youth, and low-skilled workers. Amidst this, some found themselves ostracized by landlords and neighbors. Rural migrant laborers who faced wage reductions and substantial food insecurity opted to return to their villages until their workplaces reopened. Others, due to transport disruptions and halted business activities, faced the dilemma of either seeking refuge with relatives or initiating informal business endeavors in Hawassa.

Simultaneously, the prices of essential commodities skyrocketed due to misinformation, lockdown measures, and the economic crisis intertwined with the pandemic. This sentiment was echoed by a majority of workers, who struggled to make ends meet. One informant recounted:

A kilo of potatoes, once priced at 15 EB (0.27 $), shot up to 30 EB (0.55 $), while a kilo of onions rose from 20 EB (0.37 $) to 45 EB (0.82 $). Even a small loaf of bread surged from 5 EB (0.092 $) to 2 EB (0.034 eurocents) (Interview, March 2023).

Other workers recalled their inability to procure essential supplies from cooperative union shops due to lack of a Kebele’s identity card, further intensifying the challenges faced by women and fostering pessimism about the future.

The transition from the constraints of rural family life to an urban setting was initially liberating for many young migrant workers, offering new freedoms, choices, and aspirations. These factors predominantly led to their persistence amidst harsh working and living conditions in cities. However, as uncertainty escalated and progress stagnated, faith in the future wavered, imperiling their outlook. The COVID-19 scenario ushered in profound uncertainty for workers, necessitating a recalibration of personal expectations, truncating envisioned futures, and fostering a heightened focus on religious beliefs during this arduous period.

The pandemic also brought about other predicaments, including stigma and discrimination. During our focus group discussion, one employee disclosed:

Many people mistakenly associated the Coronavirus with a ‘Chinese’ ailment, assuming that park workers frequently interacted with Chinese individuals. These baseless beliefs resulted in repeated exclusion from neighborhoods and severe threats against me ( FGD, April 2023).

Additional responses mirrored this sentiment, such as, ‘‘I was handed an eviction notice and given three days to vacate the premises. It was harrowing, and my next steps remain uncertain.’’ Some reports indicated that despite a 200 EB (3.66 $) hike in rent, access to water, sanitation, and hygiene services remained limited.

For the urban poor, access to fundamental human needs remains a paramount challenge. The depreciation of the Ethiopian Birr has exacerbated food insecurity among the urban poor. Demeke et al. [46] offer an insight into the income and cost of living status of female HIP workers in mid-April 2020. The study underscores high levels of food insecurity, with stark disparities between those remaining in Hawassa and those who have left. About 60% of respondents in Hawassa and 44% of those who departed voiced concerns about lacking adequate food in the past 7 days.

5.4 Outside the city

As narrated by a former employee of the park, the provision of lunch for workers by the company was marked by a less than stellar quality. While it managed to be relatively satisfactory, the daunting task of sustaining three meals a day had transformed into an insurmountable challenge. In a poignant twist of fate, she found herself in a solitary existence within an isolated area, her once-shared living space now vacant due to her roommates’ departure to reunite with their families. Another worker, reflecting on her personal odyssey through the COVID-19 era, shared her narrative, ‘‘I embarked on a journey to my family’s residence in the Central Ethiopia Regional State, specifically in the Kemebat Temabaro zone. However, shackled by financial constraints and the towering expectations of my family, my stay there could not extend beyond two weeks. Ultimately, I found myself returning to Hawassa.’’ Her account painted a vivid picture of the intricate interplay between individual aspirations and economic realities.

While the impact on the IP sector has undoubtedly been profound, the agricultural domain has weathered a relatively milder impact. This pattern of divergence aligns with the observed lower incidence of COVID-19 in rural areas [63]. Yet, the pandemic’s far-reaching consequences have spawned a plethora of distortions in the delicate fabric of rural–urban dynamics. Within the rural setting, the farming community has raised its collective voice in protest against the ruptured supply chains, the fracturing of market relationships, and the dearth of governmental support [64]. These grievances echo the dissonance that has taken root amidst the backdrop of unforeseen upheavals. According to one former HIP worker:

During this challenging time of COVID-19, it feels like we have been forgotten by the government. Everyone seems to prioritize investors, which often disappoints me (Interview, March 2022).

It is within the framework of these disruptions that young individuals emerge as a segment disproportionately susceptible to the shocks of an unstable economy. For HIP workers, this vulnerability has prompted the adoption of a spectrum of strategies aimed at ensuring their survival. Firstly, they have continued to navigate the realm of life within Hawassa by extending mutual support to their fellow dormitory mates and colleagues. Secondly, a considerable cohort of workers has found themselves compelled to retreat to the familiar embrace of their family homes, where the bonds of kinship provide a semblance of solace. Meanwhile, the remaining contingent of individuals has ventured into the realm of entrepreneurial or informal occupations within the urban expanse. From vending bananas to peddling avocados, this adaptive approach serves as a testament to their resilience in the face of adversity.

In this crucible of unprecedented challenges, the individual stories of the park employee, the migrant worker, and the farmer intertwine to form a multifaceted narrative reflective of Ethiopia’s evolving landscape. The journey from the subpar lunchroom to the familial haven in rural regions, and the transition from bustling urban factories to the bustling streets of urban vending, encapsulates the diverse strategies employed to endure the harsh winds of change. As the world grapples with the lingering impacts of COVID-19, these stories stand as a testament to the human spirit’s tenacity in the face of adversity.

6 Government promises and responses

Both investors and the Ethiopian government conceived the park as a center for leveraging affordable labor essential for producing low-cost garments. For Ethiopian leaders, drawing in such FDI serves a strategic goal: enhancing foreign exchange reserves, creating jobs, and spearheading a structural evolution in the manufacturing arena. Key policy-makers and decision-makers consistently promote the inception and management of IP initiatives as crucial levers for economic growth. Arkebe Oqubay, ex-mayor of Addis Ababa and special advisor to the Prime Minister, is a staunch proponent of state-guided industrialization, both in Ethiopia and across Africa. He emphasizes the proactive, developmental role that states in developing nations must assume [65]. He further argues that such strategies can address the barriers of industrialization in scenarios where domestic entrepreneurs grapple with limited capital access and capabilities, curbing their global competitive edge [15]. At the same time, the influx of export-driven FDI can bolster productivity and promote the spread of high value-added ventures, creating employment avenues for the swelling workforce, especially the less-skilled and migrant women. Yet, as Hardy & Hauge [22] articulate, although this model has historically facilitated swift industrial progress, the inherent alliance between business and state often aims to curtail labor’s influence. In a critique of dominant development paradigms, Selwyn [66] sheds light on the elitist stance that perceives human labor merely as a developmental asset, justifying labor-related inequities, exploitation, and suppression.

After the first COVID-19 case emerged, the Ethiopian government swiftly adopted various measures endorsed by the World Health Organization.Footnote 9 These actions were aimed at both keeping COVID-19 infections under control and mitigating the pandemic’s economic repercussions. These encompassed public education initiatives emphasizing the importance of regular hand washing, maintaining physical distance, contact tracing, self-isolation, and quarantine. In an innovative approach, the government-owned telecommunications provider, Ethio-Telecom, utilized mobile phone ring tones as part of a concentrated media campaign to encourage people to observe hygiene practices, maintain distance, and wear face masks. This initiative has demonstrated positive outcomes.

In a country home to over 110 million population, Ethiopia opted against a blanket lockdown. While it implemented measures like border controls, school closures, and the promotion of social distancing, an outright lockdown was not pursued. The rationale was evident: in contrast to wealthier countries, the living conditions and limited resources of many Ethiopians would make strict lockdown measures impractical and burdensome. As Oqubay quoted a government representative, ‘‘the government could not endorse a lockdown that would be tough to enforce and carry substantial social costs ’’.

Even without a countrywide lockdown, a six-month state of emergency was enacted from March to September 2020. This encompassed travel bans, restrictions on public assemblies, educational institution closures, and the institution of dedicated COVID-19 committees at different administrative tiers. For this study’s scope, we primarily centered our attention on economic actions, despite the array of policy measures that touched upon public health, governance, social considerations, and potential confinement strategies.

Keen on cushioning the economic shock of the virus, Ethiopia put forth several economic interventions (Table 3). These encompassed tax reliefs, annulment of tax debts and property levies, employment tax reductions, infusions of liquidity into banking institutions, loan rescheduling, supplementary credit provisions to enterprises, and a suite of stimulus and job-centric plans.

To back investors within IPs, three salient incentives were unveiled to counterbalance the pandemic’s impact on their ventures. First, manufacturers within these parks who had suffered interrupted international orders or lost external procurement contracts were granted permissions to vend their goods domestically. Second, manufacturers were provided complimentary goods transportation through the Ethio - Djibouti Railway, spanning from the Modjo dry port to Djibouti port, facilitating trade for landlocked Ethiopia. Initiated on May 1, 2020, this facilitation was slated to conclude by July’s end. Third, Ethiopian Airlines, the state's flagship carrier, offered a six-month reduced cargo service tariff for IP-based businesses.

In addition, the Ethiopia Investment CommissionFootnote 10 enumerated other incentives tailored for IP-based manufactures, such as a 50 percent reduction on export freight charges for export-driven manufacturing businesses not depending on railway logistics due to their geographical placement. Alongside boosting the export sector with varied initiatives, the IPDC has been liaising with the Ministry of Transport to troubleshoot logistics impediments for investors. To prevent the severe blow of a complete lockdown, manufacturers were also greenlit to produce essential items like face masks. Many IP-anchored firms have since pivoted to produce masks to cater to domestic needs, with ambitions to supply other African nations in the future.

7 Conclusion

Ethiopia finds itself amidst a transformative period, marked by unparalleled social, economic, and political flux. This metamorphosis is propelled by a confluence of global and regional events, ranging from the pervasive aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ramifications of Ethiopia’s AGOA ouster, to the economic implications of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the looming specter of inflation. These challenges collectively weigh heavily on Ethiopia's evolving economy and its labor force.

The thrust of this research was to navigate the juxtaposition between the state’s optimistic portrayals of the HIP as a beacon of industrial progress and the ground realities of job volatility and production hitches amplified by the global health crisis. Ethiopia’s proactive endeavor to attract diverse investment portfolios is commendable. However, persisting labor challenges, including productivity bottlenecks and talent retention, have tinted the nation’s industrialization narrative. Our study delineates a discernible dip in exports, a pause in investments, and an upswing in joblessness precipitated by the pandemic. These findings illuminate the inherent frailties within the global economic framework, spotlighting the dire need for reinforced safety mechanisms for labor and a bolstered social support infrastructure. Furthermore, the insights derived underscore the significance of strong labor unions and collective negotiations in championing worker rights.

To insulate Ethiopia’s workers and its burgeoning IP sector from the cascading impacts of multifaceted economic shocks, a harmonized effort among key players is imperative. It is not just about economic interventions but also addressing deep-rooted vulnerabilities that predispose IP workers to risks associated with health crises. The systemic issues range from substandard wages and untenable work settings to the stark realities of urban living and the paucity of accessible healthcare.

In charting a path forward, the state’s focus should pivot towards two paramount interventions: instituting a robust minimum wage framework and championing public housing initiatives. Raising the wage bar can alleviate the compounded adversities, especially for female workers navigating layered challenges. Simultaneously, state-backed housing endeavors can mitigate the urban living hardships, presenting an oasis of stability.

In conclusion, Ethiopia’s rural-urban migrant landscape stands at a crossroads shaped by a complex web of international and local dynamics. The pandemic, while a central concern, is a mirror reflecting the multi-dimensional vulnerabilities of the system. As Ethiopia steers through this maelstrom, a multi-faceted strategy is indispensable, emphasizing labor rights, synergistic alliances, and enhanced living standards. By addressing the foundational challenges head-on, Ethiopia can set the stage for a more resilient, inclusive, and prosperous trajectory for its migrants.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

In Ethiopia, a ‘‘kebele’’ is the smallest administrative unit in the country’s administrative hierarchy. It is roughly equivalent to a neighborhood or village. Kebeles play a crucial role in local governance and service delivery. They are responsible for various community-level administrative functions, such as civil registration, local development planning, and the provision of basic services like healthcare and education. Each kebele is typically governed by an elected committee or council, and they are an integral part of Ethiopia's decentralized administrative structure.

More information on trade between the US and Ethiopia is available at https://agoa.info/profiles/ethiopia.html.

For detail and Amharic language report see: https://p.dw.com/p/3aGuV 2020.

For COVID-response in Ethiopia also see the podcast ‘‘AFRONOMICS: Responses to COVID-19 in Africa: Lessons from Ethiopia featuring Dr. Arkebe Oqubay, Senior Minister and Special Advisor to the Prime Minister of Ethiopia”, July 13, 2020 https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/podcast/2020/07/13/afronomics-responses-to-covid-19-in-africa-lessons-from-ethiopia-featuring-dr-arkebe-oqubay-senior-minister-and-special-advisor-to-the-prime-minister-of-ethiopia.

However, a survey conducted by [41] unveiled that only 31 percent of IP firms reported receiving support from the Government. Export firms were more likely to report receiving support compared to firms producing for domestic market. Among export-oriented firms, over half reported receiving some forms of support, while merely 11 percent of domestic-focused firms acknowledged having received any support.

References

Mihretu M, Llobet G. Looking beyond the horizon; a case study of PVH’s Commitment in Ethiopia’s Hawassa industrial park. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2017.

Worku W. Policy responses and social solidarity imperatives to respond the COVID-19 pandemic socioeconomic crises in Ethiopia. CEOR: 2021; 13,279-87.

Whitfield L, Staritz C. Local supplier firms in madagascar’s apparel export industry: upgrading paths, transnational social relations and regional production Networks. Econ Space. 2021;53(4):763–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20961105.

Staritz C, Leonhard P, Mike M. Global value chains, industrial policy and sustainable development—Ethiopia’s apparel export sector. Geneva: International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development; 2016.

Kaplinsky R. Globalization, poverty and inequality: Between a rock and a hard place. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press; 2005.

Whitfield L, Marslev K, Staritz C. Can apparel export industries catalyse industrialisation? Combining GVC participation and localisation: SARChI Industrial Development Working Paper Series WP 2021-01.

Gereffi G, Humphrey J, Sturgeon T. The governance of global value chains. Rev Int Polit Econ. 2005;12(1):78–104.

Wai-chung H, Coe N. Toward a dynamic theory of global production networks. Econ Geogr. 2015;91(1):29–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12063.

Selwyn B. Poverty chains and global capitalism. Compet Chang. 2019;23(1):71–97.

World Bank. A Review of Industrial Parks in Ethiopia - Policy Report, 2022. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099350011132228872/P1741950a12ef10560af5008750d1393b7. Accessed 24 March 2023.

Coe N. Geographies of production III: making space for labour. Prog Hum Geogr. 2013;37(2):271–84.

Hardy V, Hauge J. Labour challenges in Ethiopia’s textile and leather industries: no voice, no loyalty, no exit? Afr Aff. 2019;118(473):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adz001.

Barnes T, Pratap S, Shekhar K. incorporating labour research into studies of global value chains: lessons from India’s auto industry. Global Labour J. 2016;7(3):240–56.

Coe N, Jordhus-Lier D. Constrained Agency? Re-evaluating the geographies of labour, Progress in Human Geography, 2008: 35, 2 (2008), p. 221.

Oya C, Schaefer F. Politics of Labour Relations and Agency in GPNs: Collective Action, Industrial Parks, and Local Conflict In The Ethiopian Apparel Sector: 2021. SOAS.AC.UK/IDCEA

Brass T. Labour Regime Change in the Twenty-First Century: Unfreedom, Capitalism, and Primitive Accumulation. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

Das R. Capitalism and regime change in the (Globalising) world of labour. J Contemporary Asia. 2013;43(4):709–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2013.801163.

Bernstein H. Capital and labour from centre to margins. Paper presented at the Living at the margins conference, Stellenbosch, 2007.

Taylor M, Rioux S. Global labour studies. Polity, 2018.

Pattenden J. Working at the margins of global production networks: local labour control regimes and rural-based labourers in South India. Third World Quarterly. 2016;37(10):1809–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1191939.

Baglioni E, Liam C, Martin C, Smith A. Labour Regimes and Global Production. Newcastle Helix: Agenda Publishing Limited; 2022.

Coe N, Yeung H. Global production networks: theorizing economic development in an interconnected world. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Worku W. Policy responses and social solidarity imperatives to respond the COVID-19 pandemic socioeconomic crises in Ethiopia. Clin Econ Outcomes Res. 2021;13:279–87.

Admasie S. Social Dialogue in the 21st century mapping social dialogue in apparel: Ethiopia, Cornell University, 2021.

Mengistu M, Krishna P, Maaskant K, Meyer C, Krkoska E. Firms in Ethiopia’s industrial parks: COVID-19 impacts, challenges, and government response. Policy note. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2020.

National Planning Commission of Ethiopia, 2015.

Farole T. Special economic zones in Africa: comparing performance and learning from global experiences. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2011.

Weldesilassie A, Gebreeyesus M, Abebe G, Aseffa B. Study on industrial park development: issues, practices and lessons for Ethiopia. EDRI Research Report 029. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Development Research Institute, 2017.

Meyer C, Morgan H, Marc W, Gisella K, Eyoual D. The market-reach of pandemics: evidence from female workers In Ethiopia’s Ready-Made Garment Industry. Research Notes: (2021) World Development http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Lansdowne H, Lawson J. Southeast Asian Workers in a Just-in-Time Pandemic, in Victor V. Ramraj (ed.), (2021) Covid-19 in Asia: Law and Policy Contexts; online ed, Oxford Academic), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197553831.003.0030

Ford M, Ward K. COVID-19 in Southeast Asia: implications for workers and unions. J Ind Relat. 2021;63(3):432–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221856211000097.

Baas M. Labour Migrants as an (Un) controllable virus in India and Singapore. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 2020.

Wu M, Ye H, Niu Z, Huang W, Hao P, Li W, Yu B. Operation status comparison monitoring of China’s Southeast Asian industrial parks before and after COVID-19 using nighttime lights data. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf. 2022;11:122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11020122.

Bui H, Duong D, Pham Q, Mirzoev T, Bui ATM, La QN. COVID-19 stressors on migrant workers in vietnam: cumulative risk consideration. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168757.

UNIDO. Responding to the Crisis: Building a Better Future; UNIDO: Austria, 2020.

IMF. Policy Response to COVID-19 https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-andcovid19/ Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19, 2022.

De Vet M, Jan M, Nigohosyan D, Ferrer J, Gross A., Kuehl S, Flickenschild M. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on EU industries, policy department for economic, scientific and quality of life policies directorate-general for internal policies: European Union, 2021.

World Bank. How COVID-19 is affecting companies around the world, report, 2021. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2021/02/17/how-covid-19is-affecting-companies-around-the-world

Li D, Zhao S, Wang X. Spatial governance for COVID-19 prevention and control in China’s development zones. Cities. 2022;131:104028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.104028.

Le T. Reserve Army of Ho Chi Minh City: migrant workers in the Ho Chi Minh city’s industrial parks and processing export zones under the impacts of COVID- 19 pandemic. Social Identities. 2022;28(5):295–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2022.2114893.

Mengistu A, Krishnan P. Maaskant K, Meyer C. Firms in Ethiopia’s Industrial Parks: COVID-19 Impacts, Challenges, and Government Response. Policy Note. Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2020.

African Development Bank Africa’s Economic Performance and Outlook Amid Covid–19, 2020. https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/afdb20-04_aeo_supplement_full_report_for_web_0705.pdf

World Health Organization, Ethiopia 2020: https://www.ephi.gov.et/images/pictures/pic_2011/pic_2012/First-English-Press-release-1.pdf

Worldometer Report Coronavirus. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed 14 Feb 2022.

Mulat A, Tadesse S, Amogne A. The effects of COVID-19 on livelihoods of rural households: South Wollo and Oromia zones, Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2021;7(12):e08550.

Demeke E, Hardy M, Kagy G, Meyer C, Witte M. The impact of COVID-19 on the lives of women in the garment industry: evidence from Ethiopia. 2020: Living Paper Version 1.

World Bank. On The path to industrialization: a review of industrial parks in Ethiopia, Washington DC, 2022. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099350011132228872/pdf/P1741950a12ef10560af5008750d1393b7c.pdf

Harris D, Baird S, Ford K, Hirvonen K, Jones N, Kassa M, Meyer C, Pankhurst A, Wieser C, Woldehanna T. The impact of COVID-19 in Ethiopia: Policy Brief, Oxford Policy Management, 2021.

EEPRI Economic and Welfare Effects of COVID-19 and Responses in Ethiopia: Initial insights, Ethiopian Economics Association, 2020.

Jobs Creation Commission Ethiopia, 2020.

Ali K. https://ethiopianbusinessreview.net/pandemic-defying-job-creation-buy-itanyone 9th Year, August 30–September 30, 2020. No. 90

Demiessie H. The effect of Covid-19 on macroeconomic stability in Ethiopia: Uncertainty shock impact, transmission mechanism and the role of fiscal policy, 2020.

IPDC. Industrial Parks Development Corporation. https://www.ipdc.gov.et. Accessed 21 June 2023.

Krishnan P, Krkoska E, Maaskant K, Mengistu A, Meyer C. Firms in Ethiopia’s industrial parks COVID-19 impacts, challenges, and government response. IGC, 2020.

Ethiopia Investment Commission. 2017.

O’reilly M, Parker N. Unsatisfactory saturation: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2013;13(2):190–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446106.

Fink M. Gronemeyer R, Rössner H. Labour turnover and absenteeism in the textile industry: Causes and possible solutions. Literature Review with A Focus on Ethiopia, 2021.

Halvorsen K. Labour turnover and workers’ well-being in the Ethiopian manufacturing industry Christian Michelsen Institute, Norway, 2021.

Barrett P, Baumann-Pauly D. Made in Ethiopia: challenges in the garment industry’s new frontier. New York: NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights; 2019.

Caria S. Industrialization on a knife’s edge productivity, labor costs and the rise of manufacturing in Ethiopia. (2019). Policy Research Working Paper 8980.

Beatrice G. Textile and garments in Ethiopia: a new sourcing destination. Report paper, 2021.

ILO. COVID-19: Challenges and Impact on the Garment and Textile Industry, 2020.

Teshager K, Chofana T. COVID-19 policy responses and equity impact in Ethiopia, INCLUDE Secretariat, 2021.

Müller-Mahn D, Kioko E. Rethinking African futures after COVID-19. Afr Spectr. 2021;56(2):216–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/00020397211003591.

Oqubay A. Made in Africa: Industrial policy in Ethiopia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Selwyn B. Elite development theory: a labour-centred critique. Third World Quarter. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1120156.

MoH. National Comprehensive COVID-19 Management Handbook; MoH: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2020.

MoLSA. COVID-19 Workplace Response Protocol; MoLSA 2020: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2020.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the former and current HIP workers who shared their very limited time and spoke to us about their lives. Thanks to Ding Fei (PhD) and Daniel Mains (PhD) for commenting on early drafts of this paper.

Confidentiality and anonymity

The privacy and confidentiality of the participants were strictly maintained throughout the study.

Funding

The authors have not received any financial grants from other governmental and non-governmental organizations to do this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Robel Mulat and Yohannes Gezahagn were involved in the study conception and design and drafting manuscript preparation equally. Both authors reviewed the results. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research study adheres to the principles of ethical conduct in research involving human subjects. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the local Ethics Committee of Dilla University (07/11/2020 SPH) and the University Gondar College of Social Science and followed the applicable laws and regulations governing human subject’s research in Ethiopia. The following ethical considerations were addressed and implemented throughout the research process. The informed consent written by the university was provided to the informant prior to the basic data collection. The authors, based on the provided inclusion criteria, selected eligible participants for the study. Following that, the eligible participants were asked about their willingness to participate in the study and informed about the objective of the study. The reliability and validity of the data were assured through a briefing of the overall purpose of the study to the participants, and to ensure their confidentiality, the researchers informed them that they could decline participation if they were unwilling to be involved. In the meantime, the researchers provided informed consent for those who are able to write and read; however, they were reading aloud to the participants traced as being illiterate. Following that, they agreed and signed the informed consent after hearing and reading the provided document.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mulat, R., Gezahagn, Y. Industrial promises, employment precarity, and disrupted production in the shadow of global pandemics. Discov Sustain 5, 368 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00468-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00468-z